Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Week 10: Online harassment and its consequences for the digital citizen community.

Social media, where digital communities are strongly active and allow people to have the right to freedom of speech. Recently, there have been a lot of concerns across platforms that directly threaten users and one of them is online harassment. Online harassment refers to threats or other abhorrent behaviours targeted specifically at youth through new technology channels, such as text messaging or the Internet, or uncovered online about youth (Jones, Mitchell and Finkelhor 2012, p.54). As it brings back high risk to victims that can influence badly on mental health and behavioural problems, hence, it needs to be thoroughly addressed to reduce and prevent the worst situation from occurring.

In many pieces of research, there is a variety of harassment such as offensive name-calling, purposeful embarrassment, physical threats, sustained harassment, stalking, and sexual harassment (Duggan, 2017) and among them, the most common types that happen online are offensive name-calling, purposeful embarrassment and sustained harassments. In addition, another typical type of online harassment is cyberbullying - "an act of sending or publishing mean, hurtful, or intimidating text or images via the Internet, cell phone, or other electronic device" through websites including but not limited to chat rooms, instant messaging, emails, and social networking sites (Feinberg and Robey 2009, p.26). Besides those types, online harassment can exist in many forms, such actions include the spreading of false information, abusive direct messaging, and even the distribution of private information without consent, including sexual images. If those who commit online harassment single out a person based on an aspect of their perceived or actual identity - for example, their gender, sexual orientation, race, religion, or disability-those protected characteristics (Haslop, O’Rourke and Southern 2021, p.1420).

There is no doubt that this phenomenon will leave consequences that have negative impacts on digital citizens. Some of them could affect the self-esteem and the online presence of a part of the user like emotional discomfort, self-censorship, and withdrawal from social media and other online platforms (Vitak et al. 2017, p.1233). Moreover, the worst situation as long-term emotional trauma when numerous studies have indicated that victims of online harassment may suffer from a series of negative effects of stress, worry, fear, panic attacks, and suicidal ideation in severe conditions (Haslop, O’Rourke and Southern 2021, p.1421).

For more details, I will analyse the Snowflake generation as an example. This term is indicated to young people, particularly university students to make fun of their alleged intolerance and easily offended disposition (Nicholson, 2016). Haslop, O’Rourke and Southern have analysed and deduced a conclusion about this generation: these ‘snowflakes’ are too sensitive and often encounter derogatory, abusive, and harassing internet communications. The survey found that one-quarter of the students were harassed online or thought they were themselves. Overall, this cohort of research participants indicated that a variety of unwelcome, abusive, and harassing communication could well occur when they interacted with other peers online, thus appearing to demonstrate their belief in these practices being common in such digital spaces. The study also identifies that transgender and female students report their experience of online harassment more often than their male-identified counterparts. Based upon such findings, social inequalities between groupings of gendered individuals are influenced by deep-rooted gendered injustices in a digital environment that is masculinised (2021).

Therefore, some actions need to be taken to prevent or even end up consequences of online harassment. The most basic thing still comes from the consciousness of each of us by raising awareness and advocacy in resisting and condemning bullying or threatening others online. Furthermore, instead of deactivating individuals, all social media platforms should provide options such as blocking a harasser, banning people who harass others repeatedly, or making it simple for users to convert to a limited version of their account that only permits a select group of users to interact. Algorithms and machine learning techniques could be a good way to detect harmful language and content that are always evolving to better classify those harassments. (Vitak et al. 2017, p.1240).

References:

Copp, J.E., Mumford, E.A. and Taylor, B.G. (2021) 'Online sexual harassment and cyberbullying in a nationally representative sample of teens: Prevalence, predictors, and consequences,' Journal of Adolescence, 93(1), pp. 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.10.003.

Duggan, M. (2017) Online Harassment 2017. http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/07/11/online-harassment-2017/ (Accessed: November 17, 2024).

Feinberg, T. and Robey, N. (2009) 'CYBERBULLYING,' The Education Digest, pp. 26–31. https://www.proquest.com/openview/df7b85db5268ac4d18d07478e8fe197f/1.pdf?cbl=25066&loginDisplay=true&pq-origsite=gscholar.

Haslop, C., O’Rourke, F. and Southern, R. (2021) '#NoSnowflakes: The toleration of harassment and an emergent gender-related digital divide, in a UK student online culture,' Convergence the International Journal of Research Into New Media Technologies, 27(5), pp. 1418–1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856521989270.

Jones, L.M., Mitchell, K.J. and Finkelhor, D. (2012) 'Online harassment in context: Trends from three Youth Internet Safety Surveys (2000, 2005, 2010).,' Psychology of Violence, 3(1), pp. 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030309.

Nicholson, R. (2016) '‘Poor Little Snowflake’: the defining insult of 2016.,' The Guardian [Preprint], (28).

Vitak, J. et al. (2017) 'Identifying Women’s Experiences With and Strategies for Mitigating Negative Effects of Online Harassment,' CSCW ’17: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, pp. 1231–1245. https://doi.org/10.1145/2998181.2998337.

0 notes

Text

Week 9: How can a gaming community be formed through social games and live streaming?

With the rise of technology in the digital era, video games (especially social games) gradually become a central part of binding people together through interaction and communication in games. Besides, forming real communities, live streaming is a way for people to get to know each other more easily, helping them find people who share their interests. In this blog, I will indicate the contribution of social games and live streaming to build up a community.

Social games (or social network games) are applications that leverage SNS resources and infrastructure and are characterized by asynchronous gameplay and multiplayer game mechanics (Omori and Felinto 2012, p.2). That means these are online games that adapt your friendship ties for play purposes while accommodating your daily life routines. They start exploding in the late 2000s - early 2010s by using a player’s ‘friend’ network to acquire and retain new players. Several examples of social games can be mentioned such as Fortnite, Among Us,... In these games, some features encourage social interaction between players while experiencing that kind of game. In general, this mainly has to do with the number of players who participate in the play itself, are present during the play, or are simply observers (Stenros, Paavilainen and Mäyrä 2009, p.83). To specify, in Among Us, people can cooperate by completing tasks, discussing together to find the Imposter on the spaceship and eliminate them,... Moreover, cross-platform play is supported in this game when players can play with friends between PC, mobile, or console.

Another factor that can help connect people to build up a community is live streaming. To explain, live streaming is platform-based, often live but not always. In other words, with social live streaming, everybody can create shows for himself or herself and broadcast them in real time. All the users' activities happen in real time; social live streaming is synchronous compared to other social media (Scheibe, Fietkiewicz and Stock 2016, p.7). In addition, streaming is extremely lucrative when streamers can monetise from it and at the same time, the audience can interact, communicate and learn directly what they want from that streamer. Through that, some communities can be formed based on the admiration, and respect of a group of people for that streamer as well as their content. Livestreaming can develop an atmosphere that reflects the streamer's attitudes and values and thereby creates a friendly feeling between the streamer and the viewer. This is also an important element in forming a healthy community (Hamilton, Garretson and Kerne 2014, p.1319). Furthermore, many streamers choose to live-stream just simply because they want to build communities. For them, streaming serves as their main means of networking with and bringing those friends together (Hamilton, Garretson and Kerne 2014, p.1319). Hence, they can hang out with genuine viewers and blur the gap between fans and streamers.

In conclusion, both live streaming and social games work well with each other to build a true community. Anyone can just go there to find a community that fits them and grow in that setting.

References:

Hamilton, W.A., Garretson, O. and Kerne, A. (2014) 'Streaming on Twitch: Fostering Participatory Communities of Play within Live Mixed media,' CHI ’14: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1315–1324. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557048.

Omori, M.T. and Felinto, A.S. (2012) 'Analysis of motivational elements of social games: A puzzle Match 3-Games study case,' International Journal of Computer Games Technology, 2012, pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/640725.

Scheibe, K., Fietkiewicz, K.J. and Stock, W.G. (2016) 'Information behavior on social live streaming services,' Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice, 4(2), pp. 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1633/jistap.2016.4.2.1.

Stenros, J., Paavilainen, J. and Mäyrä, F. (2009) 'The many faces of sociability and social play in games,' Proceedings of the 13th International MindTrek Conference: Everyday Life in the Ubiquitous Era, pp. 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1145/1621841.1621857.

0 notes

Text

Week 8: The Impact of Filters on Our Original Identity

The word “filter” has many meanings and can be understood in different ways. Originally, this term referred to describe a process where something is removed (Rettberg 2014, p.21). However, in a social media context, people usually know filters as an amazing tool to level up their appearance, beautify and enhance confidence. This blog will dive into the role of filters among various social network sites.

With its popularity that has been spread all over social media, face filters are likely to play a vital role in visual culture these days. In particular, Instagram was one of the first sites that popularise filters but now, users can use it on almost every social media platform (Rettberg 2014, p.21). The reason why people become addicted to this feature is that it allows us to make our selfies and other photos look brighter, more muted, more grungy, or more retro than real life. Through this tool, many posts and stories gain more attraction and hence, the owner of these posts and stories can increase their recognition. An interesting example of the advance in face filters nowadays is on TikTok, some filters allow users to play games when applied filter or do some challenges that can bring back more fun. For one thing, the person who came up with this new idea implies giving users a brand new perspective of the filter, when the filter is not only for beautifying but is also a good way for entertainment.

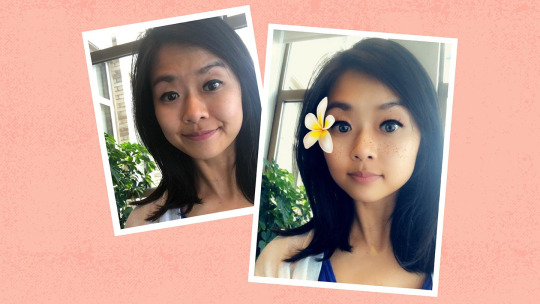

On the other hand, filters might have a lot of pros but from some perspectives, this tool can have a huge impact on our self-perception. It is clear that when applying filters, our look might be altered differently from reality. The study has shown that when virtually modifying one's appearance in real-time for self-presentational purposes, users engage in a complex process of visually depicting themselves, driven by ideal, true and transformed selves (Javornik et al. 2021, p.10). As a result, this feature of the filter can satisfy the desire to have a better look, especially online - a place where people cannot know the truth behind each post. Thus, people may regard this perfected image as superior to themselves when using face filters to present a more enhanced version of their appearances in real life (Dijkslag et al. 2024, p.2). Besides, some surveys have been conducted to indicate the psychological effect of using filters. One of them is from Isakowitsch showed that all the participants felt disconnected when they defined all of their beautified images as being ‘artificial’ which does not match at all in reality (2023, p.244). In addition, the use and exposure to face filters create a tendency to engage in upward and downward comparisons regarding one's looks with those of others, moderated probably by one's level of self-esteem (Dijkslag et al. 2024, p.2).

Those listed above have driven us to the following question: Are filters always good for us? Specifically, filters can implement animal-like features, over and distort the face, or at least virtually equip people with movement-following accessories (Barker 2020, p.208). Consequently, utilising it too much can create a disconnect between the authentic self and the filtered persona. Moreover, for women who think of the use of filters as one way of putting on a more complete face, for example, joy is usually outweighed by complications in feelings of innate attractiveness. It is obvious that not every lipstick-and-lashes filter is considered positive either; some users report irritation when a filter whitens their complexion, and the inclusion of makeup with some filters has been considered inappropriate (Barker 2020 p.213).

In short, though the benefits of filters are various, they might pose a threat to us and negatively impact our authentic selves in real life.

References:

Barker, J. (2020) 'Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of Snapchat,' Fashion Style & Popular Culture, 7(2), pp. 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1386/fspc_00015_1.

Dijkslag, I.R. et al. (2024) 'To beautify or uglify! The effects of augmented reality face filters on body satisfaction moderated by self-esteem and self-identification,' Computers in Human Behavior, 159, p. 108343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108343.

Isakowitsch, C. (2023) 'How augmented reality beauty filters can affect self-perception,' in Communications in computer and information science, pp. 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26438-2_19.

Javornik, A. et al. (2021) '‘What lies behind the filter?’ Uncovering the motivations for using augmented reality (AR) face filters on social media and their effect on well-being,' Computers in Human Behavior, 128, p. 107126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107126.

Rettberg, J.W. (2014) 'Filtered reality,' in Palgrave Macmillan UK eBooks, pp. 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476661_2.

0 notes

Text

Week 7: The Body Modification Phenomenon and Social Media Governance

Body modification is no longer a new term to every social media user since this phenomenon has gradually become more common and emerged frequently on many platforms. As a way for each individual to show off their characteristics as well as style, the phenomenon has attracted a lot of attention from those who want to highlight their unique body feature. However, some certain modification images might be considered inappropriate to appear on social media. This blog will go further into more detail on how social media governance influences perceptions and trends in body modification.

The concept of body modification was defined by Featherstone in 1999 and refers to a long list of practices which include piercing, tattooing, branding, cutting, binding and inserting implants to alter the appearance and form of the body. Based on it, people completely have the right to reassign themselves to find out the best version that they want to be. Through many decades of evolution, body modification has established a long history that takes time to get accepted by society. It is said that during the colonial, there were some differences in body modification while the one exercised through punishment must not be the same as the one expression of social collectivity (Cole and Haebich 2007, p.295). After many years, body modification has gone through a shift in societal acceptance. This can be seen in the diversity of individuals who can have opportunities to experience body modification like tattooing or piercing,... One of the significant examples has been indicated by Robert in 2012 that tattoos were first mostly used by males but until the mid-1980s, tattooing was spreading across gender lines.

Even so, body modification can sometimes cause some consequences related to a crisis about the body in other words, it is called Body Dysmorphic Disorder. To specify, this kind of disorder consists of a distressing or impairing preoccupation with imagined or slight defects in appearance (Bjornsson, Didie and Phillips 2010, p.221). That means some users may feel unsatisfied about their current body image when seeing those idealised bodies and put effort into modifying them. However, these methods might lead to negative impacts, directly affecting their health and well-being. As a result, due to its bad influence, creating a system to curate content about this phenomenon is necessary.

As we know social media could be a place to showcase any type of body art and modification. Hence, some communities and subcultures will be formed between those who have something in common. The concept of "Social Media Governance" then referred to official or informal systems that govern the activities of organisational members on social media (Linke and Zerfass 2013, p.274). In particular, the major role of the system is to describe and guide how all the members of the organization should deal with social media communication and, therefore, become communicators in online settings of participation. (Zerfass, Fink and Linke 2011, p.1034). Although this system mostly utilises platforms’ (flawed) automated systems to curate the content, some creators reflect that because it was moderated by “a machine” (algorithm), which means a “lack of human eyes going over reported content,” even the most basic stuff containing objects that are identified as ‘inappropriate’ can still be removed from the platform. Consequently, accounts like these do suggest that automated moderation systems are at best flawed; what they all have in common is that the user-creators were clearly and concisely informed of the disciplinary action (Duffy and Meisner, 2022).

On the whole, social media governance can fulfil its task well in censoring content before appearing on social networks, however, by using algorithmic curation, it might make some mistakes that affect the visibility and representation of modified bodies.

References:

Bjornsson, A.S., Didie, E.R. and Phillips, K.A. (2010) 'Body dysmorphic disorder,' Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 12(2), pp. 221–232. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2010.12.2/abjornsson.

Cole, A. and Haebich, A. (2007) 'Corporeal Colonialism and Corporal Punishment: A Cross-cultural Perspective on Body Modification,' Social Semiotics, 17(3), pp. 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330701448587.

Duffy, B.E. and Meisner, C. (2022) 'Platform governance at the margins: Social media creators’ experiences with algorithmic (in)visibility,' Media Culture & Society, 45(2), pp. 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221111923.

Featherstone, M. (1999) 'Body Modification: An Introduction,' Body & Society, 5(2–3), pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034x99005002001.

Linke, A. and Zerfass, A. (2013) 'Social media governance: regulatory frameworks for successful online communications,' Journal of Communication Management, 17(3), pp. 270–286. https://doi.org/10.1108/jcom-09-2011-0050.

Roberts, D.J. (2012) Authentic Bodies: Subcultural Reactions to the Mainstreaming of Body Modification. Michigan State University. Sociology. https://modificazione.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/authentic-bodies-subcultural-reactions-to-the-mainstreaming-of-body-modification.pdf

Zerfass, A., Fink, S. and Linke, A. (2011) 'Social Media Governance: Regulatory frameworks as Drivers of success in Online Communications,' Pushing the Envelope in Public Relations Theory and Research and Advancing Practice, 14th International Public Relations Research Conference, pp. 1026–1047. https://www.academia.edu/download/31729694/14th-IPRRC-Proceedings.pdf#page=1026

0 notes

Text

Week 6: How Social Media Influencers Encourage the Slow Fashion Movement?

Have you ever wondered how your favourite Instagram outfit inspires you to make eco-friendly wardrobe choices? This phenomenon was created by a new movement that had just emerged in the fashion industry, Slow Fashion. To bring Slow Fashion closer to an audience like us, social media influencers have become a central part of the promotion. This blog will explore more detail about the impact of influencers on Slow Fashion on consumers like us.

In 2011, Fletcher defined this term as embodying a sustainable approach consisting of different values and goals that diverge from contemporary practices. The word ‘slow’ can represent durable products, traditional production techniques or design concepts that are seasonless. Besides, Slow Fashion aims to prevent us from exploiting resources in nature and actions that meet fundamental human needs. In this phenomenon, those who design, produce and consume garments are reconsidering the impacts of selecting quantity over quality and ways to create, and consume that relate to fashion as well (Cataldi, Dickson and Grover 2017, p. 22-23). Three key principles incorporated to build up this movement are sustainability, ethical production and quality over quantity. By reducing environmental impact and promoting artisanal skills, Slow Fashion has guaranteed sustainability in products: prioritising sustainable materials as well as craftsmanship and traditional skills to support local artisans and preserve cultural techniques (Rana 2024, p. 66-67). For the ethical production criteria, Slow Fashion demonstrates transparency and ethical practices by including fair wages for workers, safe working conditions, and environmentally conscious production processes (Rana 2024, p. 66). And last one, one of the decisive features of the Slow Fashion movement is quality over quantity. in particular, each product that is made mainly focuses on creating timeless, durable pieces that withstand the test of time, both in terms of style and construction (Rana 2024, p, 66).

In order to approach a large audience with this new movement, especially in the rising digital era, many social media influencers have come up with several methods. With wonderful features on social media, influencers can easily introduce the concept and inspire their audience to pursue this new and positive kind of fashion. By posting some stylish outfits made from sustainable materials from some well-known brands that they are collaborating with, they can attract people with this unique idea and persuade them successfully. In addition, this way can encourage the audience to interact with their content and mention them in their sustainability practices, an approach to magnify their messages while continuing their sustainability mission (Jacobson and Harrison 2021, p. 162). A typical example of an influencer in promoting the Slow Fashion movement is Venetia La Manna, who is a fair fashion campaigner on Instagram. Her content mainly focuses on sustainable fashion and ethical consumerism, which often highlights the social and environmental impacts on fashion brands and educates her audience to make more ethical consumption choices.

Hence, how do these promotions from influencers impact consumer behaviour? First and foremost, consumers can immediately change their shopping habits. Several researches indicated that consumers tend to trust and engage with influencers who are perceived as authentic and genuine (Wallbaum 2023, p. 5). These people always bring the most realistic point of view to the audience and do not hesitate to reveal each behind-the-scenes. Therefore, buyers gradually purchase items that are less driven by fashion trends, and with wearing them for longer (Domingos, Vale and Faria 2022, p. 12). Next, with some effective influence marketing strategies, influencers can create awareness and attention among potential customers, impact brand attitudes, generate word-of-mouth, foster engagement and drive sales (Wallbaum 2023, p. 5) to educate followers about the benefits of Slow Fashion. Finally, communities can stimulate a more circular behaviour when it comes to the use of fashion products since there are always exist of people who share the same values (Bertilsson and Laura 2020, p. 33-34).

On the whole, social media influencers have a significant impact on consumer behaviour through different transmission methods but still have a desire to raise people's awareness and orient their mindset toward this optimistic movement.

References:

Bertilsson, E. and Laura, V.A. (2020) From Fast to Slow: Can influencers make us shop more sustainably? : A quantitative study investigating the impact of influencers and their communities on fashion purchase intent and circular behavior. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1436642&dswid=1026.

Cataldi, C., Dickson, M. and Grover, C. (2017) 'Slow fashion,' in Routledge eBooks, pp. 22–46. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351277600-2.

Domingos, M., Vale, V.T. and Faria, S. (2022) 'Slow Fashion Consumer Behavior: A Literature Review,' Sustainability, 14(5), p. 2860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052860.

Fletcher, K. (2010) 'Slow Fashion: an invitation for systems change,' Fashion Practice, 2(2), pp. 259–265. https://doi.org/10.2752/175693810x12774625387594.

Jacobson, J. and Harrison, B. (2021) 'Sustainable fashion social media influencers and content creation calibration,' International Journal of Advertising, 41(1), pp. 150–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.2000125.

Rana, N. (2024) 'Slow fashion movement,' in Emerald Publishing Limited eBooks, pp. 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83608-152-420241013.

Wallbaum, J. (2023), Tiktok’s Recent Deinfluencing Trend and its Effect on Fast-Fashion Versus Slow-Fashion Brand Valuations, Universidade Catolica Portuguesa (Portugal). https://www.proquest.com/docview/3110419306?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses

0 notes

Text

Week 5: The impact of SoundCloud and Bandcamp platformisation on Digital Citizenship.

Digital citizenship is a term that explains the norms of appropriate use and responsible behaviour regarding the use of technology (Ribble 2009, p. 15). Corresponding to traditional ideas of ‘citizenship’ which means a person is granted certain rights and responsibilities when adding ‘digital’ in front of it, these standards need to be implemented online as well. In education, it is illustrated when students have the ability to understand human cultural, and societal issues related to technology and practice legal and ethical behaviour (Ribble 2009, p. 14). Therefore, to be a good digital citizen and foster a positive online community, individuals need to have the skills and knowledge to participate in society, communicate with others, and create and consume digital content by using digital technologies effectively (NSW Department of Education).

Another concept that builds a strong bond with digital citizenship is platformisation. In the context of digital media, it has been defined as the procedure of social networking sites expanding over the internet and striving to make the external web data “platform-ready” (Helmond 2015). According to Chia and coordinators, in the marginalisation of alternate platform configurations, histories and politics, platformisation not only offers a perspective for examining global phenomena but also exerts a significant influence on those phenomena (2020). Hence, understanding clearly the notion as a process needs to be anchored in more macro-terms of investigation: how changes are effected in society through economic competition, technological structure, regulatory framework, labour dynamics, and cultural practice (Chia et al. 2020).

In their paper, Hesmondhalgh, Jones, and Rauh have examined specific examples of the impact of two platforms, SoundCloud and Bandcamp on digital citizenship (2019). Both are music streaming platforms that have been launched successfully worldwide. However, these two platforms consist of different features when engaging with artists and listeners. SoundCloud, which focuses more on operating as a social media, allows users to upload any kind of audio not just music. One of the highlight features of social interaction on SoundCloud is the waveform that enables registered users to comment directly on it. Moreover, others can interact with their music content by liking, reposting the track likewise following and becoming those users' fans. On the contrary, the main priority of Bandcamp is the artists or music creators' profits, especially monetisation when they can sell their music directly to their fans and build a strong connection with their community (Hill 2024). As a result, due to its lack of programming and modularity, Bandcamp would not be considered a platform. Most importantly, with limited API offers, users can access their own sales data and merchandise orders but are unable to take it seriously in terms of interacting with the data.

In general, platformisation has contributed to shaping the characteristics of digital citizenship through different ways of operating and unique features that only each platform has.

References

Chia, A. et al. (2020) 'Platformisation in game development,' Internet Policy Review, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1515.

Helmond, A. (2015) 'The platformization of the Web: Making web data platform ready,' Social Media + Society, 1(2), p. 205630511560308. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115603080.

Hesmondhalgh, D., Jones, E. and Rauh, A. (2019) 'SoundCloud and Bandcamp as alternative music platforms,' Social Media + Society, 5(4), p. 205630511988342. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119883429.

Hill, J. (2024) Bandcamp vs SoundCloud, How Do You Choose? https://www.hitpaw.com/audio-tips/bandcamp-vs-soundcloud.html.

NSW Department of Education (2024) What is Digital Citizenship? https://www.nsw.gov.au/education-and-training/digital-citizenship/about.

Ribble, M. (2009) 'Passport to Digital Citizenship: Journey toward Appropriate Technology Use at School and at Home.,' Learning and Leading With Technology, 36(4), pp. 14–17. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ904288.pdf.

0 notes

Text

Week 4: Can foreign reality TV shows create a significant impact on attracting online communities when imported to Vietnam?

Reality TV shows have been gaining greater shares of viewership across different audience groups largely because of their potential that widen the avenue for the sharing of opinions and driving argumentative discourse (Deller 2019, p. 153). The shows are inclusive of many forms such as gamedocs, dating programs, talent shows, and reality sitcoms amongst others (Murray and Ouellette). The Vietnamese market has also seen a significant penetration of foreign television programs. The recent reality TV formats acquired for broadcast in Vietnam include: 'Running Man,' '2 Days 1 Night', 'Brother Overcame a Thousand Thorns,' 'Street Woman Fighter.' These shows were received with phenomenal success in their home countries, where they left a deep impression on their viewers. A question remains whether they would keep their phenomenal appeal when they are adapted to the Vietnamese culture.

Street Woman Fighter Vietnam (Nữ hoàng vũ đạo đường phố) is a real dance competition adapted from the original Korean format. Its first episode was released on July 27th, and it features six competing crews including So Fire, F.E.D, OOPS!, HanoiXGirls, SSWarriorZ, and Salad. All dance crews contain well-recognised female dancers of the industry with different styles and genres.

Korea has been known as the birthplace of a variety of well-known reality TV shows. Understanding that Vietnam has the potential, with a large number of talented female dancers whose ability in both choreography and competitive dancing is equal to the international standard, the producers of the original show decided to choose Vietnam as the first foreign host for this program. This initiative aims to provide a platform for young dancers to showcase their talents and creativity (Phan Trai 2024).

In order to set a strong and long-lasting foundation the show has strived to maintain the original format to attract viewers who are used to the former Korean version. However, since the production is now based in Vietnam, it has to fit the local culture. An instance of this is the performance of the dance crew F.E.D during the Mega Crew mission, in which they used Vietnamese music and set up the formation in a star shape, representing the emblem on the national flag. Specifically, the emergence of well-known faces in the Vietnamese entertainment industry, such as popular judges and master hosts Hari Won, Diep Lam Anh, Gil Le,... has contributed to its appeal and viewership.

The show broadcast both through the HTV7 channel and YouTube, enjoyed an incredibly active online audience. This is somewhat understandable considering the quality of social media viewership, which essentially tends to be a communicative practice, best linked with the scheduling of a live show (Deller 2019, p. 157). Consequently, it places viewers in a position where they have topics of commonality they can discuss each week on various social media platforms. It is a sense of collective empowerment that provides greater ease and immediacy, especially when they can identify and unite behind a common interest such as fandom for a television series (L'Hoiry 2019, p. 11). Notably, the diverse responses to individual performances can elicit a whole gamut of opinions; where one may show eagerness, the same feelings might not be shared by another person. These differences in views mostly result in the creation of different online communities based on a wide array of outlooks.

In short, Vietnam opens a very huge opportunity to produce reality TV shows based on foreign formats, owing to the diverse audience demographics in the country. However, more is indeed required to be done to enhance quality and creativity by the producers themselves to catch more viewership in the long term.

References:

Deller, R.A. (2019) Reality television: The television phenomenon that changed the world [Preprint]. doi:10.1108/9781839090219.

Murray & Ouellette, ‘Week Four Reality TV Case Study 2023 Slides’, MDA20009 Digital Communities, Learning materials via Canvas, 2023, viewed 04 October 2024.

L’Hoiry, X. (2019) ‘Love Island, social media, and Sousveillance: New Pathways of challenging realism in reality TV’, Frontiers in Sociology, 4. doi:10.3389/fsoc.2019.00059.

Phan Trai (2024) Show đình đám hàn quốc ‘Nữ hoàng vũ đạo đường phố’ đến Việt Nam, Tạp chí điện tử: Người Đưa Tin. Available at: https://www.nguoiduatin.vn/show-dinh-dam-han-quoc-nu-hoang-vu-dao-duong-pho-den-viet-nam-204649700.htm#:~:text=Nh%E1%BA%ADn%20th%E1%BA%A5y%20Vi%E1%BB%87t%20Nam%20c%C5%A9ng,v%C3%A0o%20cu%E1%BB%91i%20th%C3%A1ng%207%2F2024.(Accessed: 04 October 2024).

0 notes

Text

Week 3: Hashtags - a powerful feature that helps engage digital communities on Tumblr.

Hashtags are now being used widely on many different platforms, especially Tumblr, which is considered one of the first social media sites to use hashtags to create a community.

According to Sprout Social, hashtags are defined as words and numbers with the # symbol in front that can classify and track content on social media (2024). This means that adding a # symbol in front of a keyword related to the topic allows users to link their posts to align with the same topic content (Rauschnabel, Sheldon & Herzfeldt, p. 473).

Since it was created and became an indispensable part of the platform, hashtags have played an essential role in developing and enhancing user experience:

1. Discover a variety of content

Hashtags can assist users in discovering more content that relates to their interests. Ta’amneh and Al-Ghazo assumed in their article that hashtag activism effectively garners attention and raises awareness for many important issues (2021, p. 12). Therefore, numerous new hashtags are emerging and gaining traction among users.

2. Build and engage in a community

With others who share their interests, users can engage and form new communities. This is probably because, on Tumblr, hashtags give users a more intimate way to strategically express their ideas, feelings, and opinions—even when they write in areas of the platform that they are aware are public (Brett & Maslen 2021, p. 12). When movements are accompanied by hashtags, they can grow virally among social media users and naturally reach like-minded people and organisations (Saxton et al. 2015, p. 2).

3. Trend tracking

When hashtags are created and established in communities, they will suddenly become a trend that attracts a lot of attention. On social media, people frequently follow and talk about popular subjects. This apparent behavioural pattern is being examined, along with the recently acquired knowledge of machine learning, in this seemingly fascinating field of study (Shams, Hoosain & Noori 2020).

One of the key hashtags used effectively by a female community on Tumblr is #bodypositive. This hashtag was made to increase awareness of the variety of femininity and body types. These communities have the power to subvert the conventional notion of beauty and give more people a sense of acceptance and beauty (Reif, Miller and Taddicken 2022, p. 4-5). Due to its anonymity feature, Tumblr has become a preferred choice for numerous adolescent feminists (Keller 2019, p. 7), serving as a stage for them to reveal their individuality and share their perspectives. As a result, this phenomenon has attracted a lot of attention from female users who were previously self-conscious, encouraging them to be more self-assured and not to be flaunt their attractive appearance on social net working sites.

#bodypositive aligns with some other hashtags that also relate to the same content

In conclusion, hashtags have a significant impact on connecting people with similar ideas or interests, helping them find each other, and gradually forming various digital communities. The emergence of these communities on platforms like Tumblr appears to bridge the gap between individuals, bringing them closer and enhancing their comfort while using social networks.

References:

Brett, I. and Maslen, S. (2021) ‘Stage whispering: Tumblr hashtags beyond categorization’, Social Media + Society, 7(3), p. 205630512110321. doi:10.1177/20563051211032138.

Hashtags: What they are and how to use them effectively (2024) Sprout Social. https://sproutsocial.com/insights/what-is-hashtagging/

Keller, J. (2019) ‘“oh, she’s a Tumblr feminist”: Exploring the platform vernacular of Girls’ Social Media Feminisms’, Social Media + Society, 5(3), p. 205630511986744. doi:10.1177/2056305119867442.

Rauschnabel, P.A., Sheldon, P. and Herzfeldt, E. (2019) ‘What motivates users to Hashtag on social media?’, Psychology & Marketing, 36(5), pp. 473–488. doi:10.1002/mar.21191.

Reif, A., Miller, I. and Taddicken, M. (2022) ‘“Love the skin you‘re in”: An analysis of women’s self-presentation and user reactions to selfies using the Tumblr hashtag #bodypositive’, Mass Communication and Society, 26(6), pp. 1038–1061. doi:10.1080/15205436.2022.2138442.

Saxton, G.D. et al. (2015) ‘#advocatingforchange: The strategic use of hashtags in social media advocacy’, Advances in Social Work, 16(1), pp. 154–169. doi:10.18060/17952.

Shams, M.B., Hossain, Md.J. and Noori, S.R. (2020) ‘A time series analysis of trends with Twitter hashtags using LSTM’, 2020 11th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/icccnt49239.2020.9225349.

Ta’amneh, I.M. and Al-Ghazo, A. (2021) ‘The importance of using hashtags on raising awareness about social issues’, International Journal of Learning and Development, 11(4), p. 10. doi:10.5296/ijld.v11i4.19139.

1 note

·

View note