"History is the witness that testifies to the passing of time; it illumines reality, vitalizes memory, provides guidance in daily life and brings us tidings of antiquity." Cicero (106 BC - 43 BC)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

My brief 500 word analysis of "Becoming Mexican American," an excellent work by historian George J. Sanchez.

In, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945, George J. Sanchez presents an evolutionary history of the migration of Mexican people into Los Angeles and how they, over two generations evolved into Mexican Americans, or Chicanos. He begins by explaining why the migrants left Mexico, and the routes they took to reach the border, as well as explaining that the destination for many were urban areas within Mexico, or in Northern Mexico, in search of work away from the their rural agrarian homes. Sanchez describes how wages were higher along the border, and how migration eventually stretched into the United States where labor was needed. He stresses that the original crossing point for most migrants was not the California/Mexico border, but the Texas, New Mexico and Arizona border, with migrants spending time working in the U.S., sometimes for years, before migrating to the Los Angeles area.

Sanchez describes how the Mexican migrants were subjected to Americanization programs, and to programs from the Mexican consulate to reinforce their Mexican nationalism. He delves into the social evolution of the Mexican migrant family in terms of religious conversions, musical adaptations and utilization of the media. He also tackles the cultural stereotypes which were used to categorize and diminish the modernity of Mexican families. Sanchez writes about the evolving economic and labor status of the Mexican worker and how they were challenged during the era of the Great Depression. He then discusses the second generation, or the U.S. born children, of the Mexican migrants, and how they endured much of the same prejudice and stereotypical ignorance by white culture but were able to struggle through it. They did this by way of education as exhibited and promoted by groups such as the Mexican American Movement (MAM), and he argues that it was in the pre-WWII years with these groups that Chicano history truly began.

Sanchez used what seemed like a great deal of quantitative data to buttress his assertions, presenting 15 tables, and regularly giving the reader facts and figures within the reading. While this presentation of quantitative data might have been annoying to some readers, it helped the reader understand the scope of the topic. What further aids the reader grasp the nature of the topic is a timely placed collection of photos at the beginning of part four which associates the faces of real people to the topic and visually shouts at the reader that our humanity is the subject here.

Sanchez has utilized a variety of primary sources for his monograph. He cites U.S. and Mexican government documents, periodicals, unpublished papers, and archival manuscript collections and documents. He also cites well over twenty other books and miscellaneous sources. What Sanchez claims is significant about his work is that a study and analysis of the evolutionary journey of Mexican-Americans in the Los Angeles area, during the first half of the Twentieth century, could lead to a greater understanding of the multicultural and transnational world of the late Twentieth century. Sanchez was correct in what he hoped the relevance of his work was, and there are still lessons that can be learned from it in the first half of the Twenty-first century because the world, despite current attempts at backward isolationism, is more multicultural and transnational than ever before.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hear is my analysis of this excellent World History book.

J.R. McNeill and William H. McNeill have written a book, The Human Web: A Bird’s Eye View of World History, which provides the reader with a continuous flow of historical connections among people and their environment that does not get caught in the weeds of historical intricacies. They explain in the preface that it is a book for people who want an understanding of how humanity and the human world developed without having to spend vast amounts of time reading history books. The McNeill duo, a father and son, use the analogy of webs to explain how connections developed and explain how those connections led to changes in human existence. They also analyze how those connections also led to technological advances which promoted the rise of civilizations.

The McNeill duo write about the webs that connected Metropolitan areas to their agricultural and pastoral hinterlands. They described how webs began as small local webs, which over time were connected to larger regional webs, and then to larger cosmopolitan webs through the expansion of human contact, cooperation, and competition. They then explored how this ever-expanding network of webs led to the contact between people across multiple sectors of the globe, promoting the diffusion of ideas, food crops, and broad scale technological advancements, along with many diseases. They also categorize the webs into time and place. They refer to “Old World Webs,” “American Webs,” and “Pacific Webs.” They then described the processes which caused the fusion of these webs over time.

The technique which the McNeill duo utilized of not getting caught up in the weeds of history is remarkably like the disciple of “Big History” as pioneered by Professor David Christian. Christian’s book, Maps of Time, also avoids many historical intricacies while giving the reader a big picture view of history. Avoiding the intricacies is not to say that they skip over crucial topics, only that to give a big picture view, a vast number of names and events must be left out to include the crucial historical trends. The Human Web may not begin its examination at the dawn of time as David Christian did, but it does begin its analysis at the dawn of human existence. That is still a vast amount of the past to cover and their modus operandi, or methodology, is still in line with “Big History.”

The Human Web also reminds of the ground-breaking work of Alfred W. Crosby, Jr. He also analyzed connections and transferences of ideas, technologies, foods, and diseases. Crosby referred to it as the process of exchange in his book, The Columbian Exchange, which pre-dates The Human Web by 32 years, as it was written in 1971. Crosby limited most of his analysis to cross-Atlantic exchanges, or web connections as the McNeill duo called it, between the New World and Old World. Another similarity between Maps of Time, The Human Web, and The Columbian Exchange is that Christian, the McNeill duo, and Crosby used multi-disciplinary sources in their analysis and were not limited to traditional historical records, but Crosby did it first

0 notes

Text

Watch "Debunking the myth of the Lost Cause: A lie embedded in American history - Karen L. Cox" on YouTube

youtube

This video summarizes what I, and the vast majority of historians, know to be the truth of the "lost cause" mythology, and that slavery was the fundamental cause of the Civil War, not state's rights.

0 notes

Text

I recently read the nearly 500 pages of this book by renowned Harvard historian Seymour Drescher. Here is my brief 500 word analysis.

"Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery"

Seymour Drescher analyzes the contradiction between the political and economic liberalism of Northwestern European nations, primarily Great Britain, and the slave colonies they governed in, Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery. Drescher’s book is organized into four parts that cover the history of slavery in the Atlantic World during several centuries. He begins by describing the origins and nature of slavery in antiquity, in religions, and in its transferability across “time and space.” Drescher claims that Europeans were no strangers to slavery prior to engaging in the transatlantic slave trade. He also argues that prior to the transatlantic slave trade, when the trade was a Mediterranean affair between Europeans and Muslim states, Europeans did not associate slavery with any specific race. He also discusses the paradox of the French Freedom Principle in regards to the French slave colonies.

Drescher points to the relative ease with which European were able to enter the slave trade. He discusses how the Portuguese acquired slaves along the West African coast, and how it became easier the further south along the coast they sailed due to the existence of established slave trading systems by Africans. He also briefly discussed the enslavement of Native Americans, on the path the Europeans took to developing large scale plantation slavery in their New World colonies. It seemed that slavery on the home continent for Northern Europeans was not acceptable, but it was acceptable in their colonies, as demonstrated by the Somerset decision in Great Britain and by the French Police des Noirs. Drescher then described the age of Atlantic revolutions and claimed that they had little effect on slavery in the colonies.

Drescher argues that the age of revolutions, with the obvious exception of Haiti, left slavery mostly intact in the New World colonies. He writes that by the 1830s, the primary importers of enslaved Africans were the Iberians powers, and that, “as many slaves were being delivered to Brazil and Cuba in the 1820s as has been freed by the Franco-Caribbean revolutions…” Drescher also argued that slavery continued to remain a cost-effective form of labor, and that it did not decline or end due to a greater economic feasibility from free labor. He credits its demise to abolitionist forces who engaged in a long transatlantic crusade to end slavery.

Drescher does not give sufficient credit to efforts by enslaved person in the abolition of slavery. A book published in 2009 should no longer diminish to such an extent the agency of enslaved persons. Drescher’s analysis also was very Eurocentric. I remember reading something about abolition movements in the United States, and something about a US Civil War that freed millions. That aside, Drescher has weaved together an exceptional transatlantic narrative about a topic with many branches which is bound to both please and upset many

1 note

·

View note

Link

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

When the United States annexed Texas (a former Mexican state) in 1845, many Mexicans felt that war with the U.S. was approaching. A common admiration for the U.S. and her democratic republican system, existed among Mexican political leaders prior to 1845. After all, the U.S. and Mexico were the sister republics of North America. This sentiment turned to distrust among many Mexicans with the permanent loss of the former northern Mexican state of Tejas. Under pressure from U.S. President James K. Polk, a strong proponent of U.S. expansion to the Pacific, Texas claimed its southern border at the Rio Grande River (Rio Bravo). Mexico insisted that the historical border of Tejas and Tamaulipas was the Nueces River, near current day Corpus Christi. Mexico never even recognized Tejas independence due to Gen. Santa Anna not having the legal authority, according to Mexico’s constitution, to sign away Tejas in the Treaty of Velasco. Irregardless of Santa Anna’s non-existent authority, Tejas officially became Texas with U.S. annexation, and Mexico was in no position militarily, politically or financially to alter that reality. The anti-American sentiment that resulted in Mexico from the Texas annexation made it difficult for any Mexican politician to negotiate with the U.S. and not be politically weakened. Mexico had no real political parties. She was governed by coalitions of special interest groups which swirled around rotating leaders. In 1844, control of Mexico passed to a coalition of Federalists who strengthened the power of the states resulting in a weaker central government. The annexation of Texas splintered this group of federalists. The “Moderatos” (moderates) led by President Jose Joaquin De Herrera realized that in her condition, Mexico engaging in a war with the U.S. would be disastrous. The larger group of “Puros” (pure) led by Valentin Gomez Farias preferred losing a war to the U.S. than the supposed shame of letting Tejas go without a fight. there also existed alliances of Centralist who saw a strong central government as the best way to protect their individual interests. They consisted of “Hacendados” (large landowners), the Roman Catholic Church, the remaining monarchist, and military officers keen for advancement. President Herrera attempted to gain popular support for a peaceful resolution of tensions with the U.S., but with his time in office ending, his efforts gained no ground. In the middle of this turbulent times revolts were also forming in the Mexican states. In the state of San Luis Potosi, Major General Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga commanded “El Ejercito del Norte” (Army of the North), Mexico’s largest and best trained military force. Gen. Paredes decided to march his army into Mexico City and take over the government on January 2, 1846. General Paredes claimed that his intervention was needed because President Herrera had been negotiating with a U.S. envoy, John Slidell. Slidell had been sent to negotiate with Mexico during December of 1845, for the purchase Upper California and Nuevo Mexico (New Mexico) by President Polk. Slidell was unsuccessful in his mission. President Herrera feared he would be considered a traitor for just meeting with the U.S. envoy. The Mexican government postponed the meeting using diplomatic “red tape.” Slidell, not fully understanding the precarious position that his visit had put President Herrera in, and feeling slighted by the Mexican government, reported to President Polk that his mission had failed. So, the die was cast. Mexico could not treat with the U.S., and President Polk was determined to have California and New Mexico. President Polk decided to place his dominoes in a position to provoke war, and he would use the disputed Texas/Mexico border as provocation.

Bauer, Jack K. "The Mexican War 1846-1848". Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1974.

Beezley, William H., and Maclachlan, Colin M. "Mexico’s Crucial Century, 1810-1910: An Introduction." Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“There’s nothing more American than the cowboy and more Mexican than the charro. With great imagination and meticulous research, Laura Barraclough shows what the intersection between the two reveals about the shifting grounds of U.S./Mexican ethnic masculinity and nationalism from the 1920s to the present.“

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

56 years ago today - View of some of the leaders of March on Washington for Jobs & Freedom as they march with signs, Washington DC, August 28, 1963. Among those pictured are, front row from left, John Lewis, Matthew Ahman, Floyd B. McKissick, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, Reverend Eugene Carson Blake, Cleveland Robinson, and Rabbi Joachim Prinz (in sunglasses). The march provided the setting for Dr. King’s iconic ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. (Robert W. Kelley—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images) #LIFElegends #ihaveadream #marchonwashington #MLK https://www.instagram.com/p/B1tXXMmAVZQ/?igshid=4t5l9l2iqix8

637 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I wrote a 14 page essay as an undergraduate on the role of white patriot women on the home front during the Revolution. My research for that paper was very precise and pinpointed, but I always wanted to learn more about the role of other women groups during the Revolution.

“Women in the American Revolution brings to the fore all that we have learned in the decades since the publication of the foundational essays of Linda Kerber and Jan Lewis. Bracketed by prominent historians Rosemarie Zagarri and Sheila Skemp, the essays offer diverse and compelling stories of midwives, plantation mistresses, Loyalists, Native Americans, entrepreneurs, poets, and enslaved African Americans.”

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I once delivered a 20 minute graphic presentation covering the Rape of Nanking in a history of Western Civilization class. When I finished an angry and disgusted classmate asked me how could I make them sit through that. I responded "because that horror really happened."

“Morally uncompromising, yet culturally sensitive and nuanced in his analysis, Frank Jacob offers the equivalent here of an invaluable master class in how to write the history of the Second World War. The particular topics that he tackles remain controversial and, in the case of the so-called ‘comfort women’ issue, as well as the 'Rape of Nanking,’ politically explosive; yet Jacob’s accounts of them are models of rigorous scholarship and balanced interpretation. This is an accessible work of history brilliantly fashioned not merely to increase the reader’s understanding of wartime atrocities, but to serve as an intervention, as it documents how easily a nation that wages war can hurtle down the road toward the unthinkable.”

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fort Pillow Massacre:

From April 1864 to the end of the U.S. Civil War, black regiments of the Union army charged into battle shouting the vengeance cry of "Remember Fort Pillow!" This was because at the Battle of Fort Pillow on April 12, 1864, hundreds of mostly black soldiers and their white officers were massacred after they surrendered to the Confederate forces commanded by Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. The bloody, and in many cases torturous, atrocities committed by Confederates were described by both Union and Confederate troops in graphic letters written home after the battle. Southern newspapers even praised the murderous actions of Gen. Forrest and his men in eliminating the black troops. After the Union army began allowing black soldiers to fight, Confederate leaders became enraged.

It became the "understood" policy of the Confederate government that "Negro" soldiers and their white officers would not be spared. Confederate President Jefferson Davis personally ordered captured black union soldiers executed. It was even the declared policy of Gen. Kirby Smith, commander of all Confederate forces west of the Mississippi River, that all captured blacks wearing Union uniforms would be killed. This policy of murdering surrendered or captured Union troops by the Confederacy led to the breakdown of prisoner exchanges which had been regularly occurring throughout the war. Thus POW camps on both sides began to overflow, leading thousands of POW deaths due to starvation and disease, with the Confederate death camp at Andersonville being the most notorious. Even though there exists, much documented evidence of the Fort Pillow Massacre, a visitor to the current day Fort Pillow Tennessee State Historic Park overlooking the Mississippi River, some forty miles north of Memphis, Tennessee, would learn little of the truth concerning what happened there on April 12 of 1864.

A brochure handed out at the Fort Pillow Tennessee State Historic Park claims that the Union troops received excellent treatment, that the wounded federals were treated by doctors and then transported to the first available steamer. A historical plaque near the park reads, "…to end depredations committed by the Federal garrison, Forrest, with a force from his Confederate Cavalry Corps, attacked and captured the fort. Of the garrison of 551 white and Negro troops, 221 were killed. The rest, some wounded, were captured." Not mentioned is that the vast majority of those Union deaths were the result of being killed after surrendering. Today the Fort Pillow Tennessee Historic State Park is basically a Confederate States of America museum and gift shop, with only a slight dismissive mention of the "controversy" surrounding the massacre.

John Cimprich and Robert C. Mainfort Jr., "The Fort Pillow Massacre: A Statistical Note,"Journal of American History 76 no. 2 (December 1989): 832 – 837.

Loewan, James W., Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong. New York: New Press, 1999.

0 notes

Photo

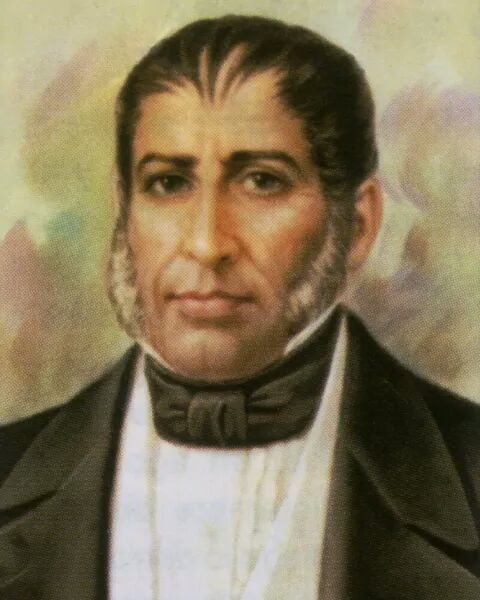

Gen. Vicente Guerrero, an Afro-Indian Mexican, was a national hero of the Mexican War for Independence from 1810 to 1821. It was Guerrero who led the republican rebel army and is credited with keeping the Mexican War of Independence from Spain alive after the deaths of the rebel priests Miguel Hidalgo and Jose Maria Morelos. It was Guerrero who convinced royalist general Agustin de Iturbide to switch side and join the rebellion, ultimately defeating Spain and winning Mexican Independence in 1821. He was also elected as the second President of Mexico, and yet the Mexican government executed him in 1831. Why? Other former rebel leaders such as Gen. Nicolas Bravo also led revolts against the new government, but if captured they were exiled from Mexico or imprisoned for a time. So why was Guerrero executed? A prominent argument is that Guerrero's ethnicity sealed his fate. Guerrero was born of an African-Mexican father and a Native American mother. One such argument was offered by Lorenzo De Zavala, a contemporary of Guerrero's, a Mexican Liberal scholar and governor who helped write the Mexican Constitution of 1824, served in the fledgling Mexican government, and later moved to Texas where he became a leader in the Texas Independence movement. De Zavala wrote several years after Guerrero's death that Guerrero was of mixed blood and most of the opposition to his presidency came from the landed elite or large land owners, generals, elite clergy, wealthy Spaniards still living in Mexico and those who still adhered to the centuries old racial caste system of Spain. These were the very people that the social and economic reforms of Guerrero's government would hurt most. President Guerrero was removed from office by Vice President Bustamante in 1829 during a revolt aided by Gen. Bravo who had just returned from exile. Due to the Conservative policies instituted by Bustamante's government, Guerrero led a revolt in 1830, but was captured and executed in January of 1831. Lorenzo De Zavala also wrote that Guerrero's execution was likely a warning to those considered socially and ethnically inferior not to dare dream of becoming president. Generally, most portraits of Vicente Guerrero display a much lighter skinned individual than written accounts describe. Another Mexican general named Antonio Lopez De Santa Anna would later use the national outrage over Guerrero's execution to win the presidency for himself. Bazant, Jan. "Mexico Since Independence", ed. Leslie Bethell (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 11 – 15.

0 notes

Video

youtube

“Nunca uso el término guerra de independencia, porque una guerra de independencia es cuando hay un invasor extranjero y uno quiere librarse de ese invasor extranjero, como era el caso de España frente a Napoleón. En este caso no, porque era la misma familia. No se podría decir que los españoles eran foráneos invadiendo Colombia porque Colombia no existía; o sea, fue fundada por España, – mejor dicho el virreinato de la Nueva Granada –, y era todo parte – provincias – de la misma nación española. […] La España allende el mar y la España ibérica.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

Here is a Spanish language discussion between two Latin American historians discussing the often buried history of the cold blooded murdering acts of Simon Bolivar, a person promoted as the great liberating "hero" of South America.

youtube

“Nunca uso el término guerra de independencia, porque una guerra de independencia es cuando hay un invasor extranjero y uno quiere librarse de ese invasor extranjero, como era el caso de España frente a Napoleón. En este caso no, porque era la misma familia. No se podría decir que los españoles eran foráneos invadiendo Colombia porque Colombia no existía; o sea, fue fundada por España, – mejor dicho el virreinato de la Nueva Granada –, y era todo parte – provincias – de la misma nación española. […] La España allende el mar y la España ibérica.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

January 16, 1917 - British Cryptographers Intercept Zimmerman Telegram

Pictured - Spoils of war promised to Mexico if it declared war on the United States.

The bulk of cables linking both sides of the Atlantic by telegram belonged to Britain, and British military intelligence flagrantly made use of this privilege by reading all the messages sent across by Germany and the United States. However, none was more important than one Britain’s cryptographers intercepted on January 16. Sent via Sweden on to Washington D.C. on American-owned cables, it was a message from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman to his ambassador in Mexico City.

Britain’s crack decoding team, Room 40, quickly decrypted the message. They found in it a proposal by Zimmerman to invite Mexico into the war against the United States, should American join the Allies. Zimmerman offered in return the Mexican territory annexed by the US following the Mexican-American war. In British hands, this message was diplomatic dynamite. For now, British Intelligence held on to it, debating over how best to use it (and how to do so without revealing that Britain regularly spied on American correspondence).

266 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A racial caste system developed in Mexico during the 300 years of Spanish rule from the years 1521 to 1821. The caste system consisted of the Peninsulares (Spaniards born on the Iberian Peninsula), the Criollos (Spaniards born in the New World), the Mestizos (those of mixed Spanish and Native American descent), the Indios (Native American Indians), and the Mulattoes (of or mixed with African descent). Less than 700,000 Spaniards, mostly men, actually settled in Mexico. The male settlers "intermarried" with indigenous women and fathered the Mestizos whose descendents currently constitute the majority of Mexico's population.

The most powerful societal group was the Peninsulares sent from Spain to rule colonial Mexico, or New Spain as they called it. Only the Peninsulares could hold high level positions in the colonial government. The Criollos were a less powerful group. Many of the Criollos were prosperous land owners and merchants. Many served in the Spanish colonial militias, but even the most successful Criollo had little to say in the colonial government. Both white castes, the Peninsulares and the Criollos, looked down upon the Mestizos because they held the racists idea that people of pure European background were superior to all others. The Indios and Mulattoes were at the very bottom of the socio-economic ladder. What all four lower caste groups had in common was a long standing frustration and anger with the oppression of the Spanish caste system. So when in 1810, a catholic priest shouted his "Grito de Dolores" (Cry of Dolores) from the town of Dolores Hidalgo in Mexico, encouraging all Mexicans to cast off the yoke of Spanish colonialism, he found a nation ready to revolt. That priest's name was Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. He was a survivor of the Spanish Inquisition, being tried on heresy charges, and he is considered the "Father of Mexican Independence."

Henderson, Timothy J. "The Mexican Wars for Independence". New York: Hill and Wang, 2009.

0 notes

Photo

20 de Noviembre, Día de la Revolución Mexicana

Archivo Casasola, Fototeca Nacional del INAH

Stay Connected: Twitter | Instagram | Facebook

265 notes

·

View notes