Victoria, 19, Archaeology & Heritage undergrad. Follow my Wordpress Blog about my studies and adventures at www.curatingvictoria.wordpress.com/ . If you like my content, please consider donating at ko-fi.com/girlarchaeologist

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

This week I had the opportunity to visit Fishbourne Roman Palace, and was very excited to see how they portray a Roman site to the public and engage their visitors. I went with my grandma, who I remember a few years ago saying to me “I don’t like museums”, although she seems to enjoy them much more now when we go together, especially if there’s something pretty to see and take photos of. We had an amazing experience there and I’ve picked out a few of the things that stood out to me to talk about; the museum area, the walk across the mosaics and the gardens. I will be writing about the “hands on” area in my next article, and following this I’ll be summing up my thoughts about how they have portrayed their site and how -theoretically- we could portray Malton Roman Fort (where my department have been excavating) to visitors if it were to be an attraction and museum in a similar way.

A picture of me standing in front of banners showing different types of artefacts

Content warning: images of and discussion of human skeletons

(And yes, I’m wearing a Pokemon T-shirt in the featured image, I had to stick an awkward photo of me in here somewhere)

My grandma looking at a model of a Roman bathhouse

History of the Site

Fishbourne Palace, located in West Sussex, is the largest surviving Roman building in Britain and dates to about 75AD. Most of the palace was excavated in 1960 by Sir Barry Cunliffe after it was accidentally discovered by a water company laying a new line over the site. The palace is so big that a museum has been built over the site to try and preserve as much of the building in situ as possible.

In size, it is approximately equivalent to Nero’s Golden palace in Rome and in plan it closely mirrors the emperor Domitian’s palace (the Domus Flavia) completed in AD 92 on the Palatine Hill in Rome. Fishbourne is by far the largest Roman residence known north of the Alps. At about 150 square metres, it has a larger footprint than Buckingham Palace.

Museum

The museum is the first part you will see on your visit, it is laid out with information on walls in a numbered sequence which gives a background to the Roman occupation of England and the context of the site. These exhibits are very text heavy, and are balanced by the display of artefacts and images & diagrams.

Panel 1 was about the discovery of the site

Panel 2 explained stratigraphy and the display demonstrated this.

Panel 3 was about the site

Panel 4 explained the Roman invasion with diagrams

As well as these more factual exhibits there are interactive activities such as building a Roman road and identifying gods by matching pictures together on a low table. The scale model of the site in the first room attracted my Grandma, allowing for a more tactile experience than viewing a local map.

A scale model map of the area. On the glass there is a diagram indicating where the modern road is.

There were also a lot of kids when I went who were all fascinated by the example weaving activity, the scale model map and the bust of Vespasian, shouting “That’s what he looks like!!”. It is so important to have such tangible links for people to be able to relate to people in the past and see even emperors as “human”.

A bust of Vespasian

The curators of the exhibition have clearly put a lot of thought into weaving multiple themes into one, for example the “imported elegance” panel, which displays wall plaster from Fishbourne, explaining how the elaborate finishes would have been done by a skilled craftsman probably from Italy, and displaying two images of wall paintings found in Italy which compare to the evidence from Fishbourne.

Panel 24: Imported elegance. The display shows wall plaster from the site, and shows wall paintings from other sites which are similar.

The final parts of an exhibition are just as important as the introduction and can leave a lasting impact on the audience, and at Fishbourne the final space has three panels, “Disaster”, “Burials”, and “The Jigsaw”.

The disaster panel explains how between 270 and 280 AD the palace was destroyed by a fire, and how it cannot be certain if the fire was accidental or deliberate, but notes that pirates were raiding the south coast at that time, a neat way of painting a picture and explaining a narrative whilst not asserting facts we don’t know, a lot of archaeologists I know would say that if we’re not sure on the facts we shouldn’t tell stories, which are vital to public engagement and understanding.

The accompanying display is a show of the destruction, with puddles of melted lead, buckled window glass and broken and discoloured pottery which has been repaired and reconstructed for the exhibit. Personally my eyes are drawn to the reconstructed pots more than the disarticulated glass. On the top shelf by comparison, there are lots and glass from the late third century that survived the fire, it’s a massive shame that my photographs didn’t survive however.

The human remains in the museum lie in a glass case.

The burials section is in association with the human remains that lie in the centre of the room which is captioned with “a pagan burial, oriented on a north-south line and discovered in the demolished ruins of the Roman Palace”, which is on the opposite side of the room to the rest if the information. This is probably due to issues to do with space, but it did confuse me having the information, remains and the explanation all in different places.

The panel explains how the ruin was salvaged after it burnt down and that people would take things of value before further demolishing the building. They say that later, probably towards the end of the Roman period, shallow burials were made in the rubble, and one grave was in the north wing which was much deeper and is still there now.

Human remains in a grave cut into the floor

The ethics of displaying human remains in museums is contentious, and I won’t go into full details here. I think it is a lovely gesture to have left the skeleton in the north wing in its final resting place. The sign accompanying the burial simply says that there was no dating evidence in the form of grave goods, but we know that the graves were cut after the palace was destroyed. I was left feeling a little bit frustrated about the lack of information about the burials, although I’m aware that specific information is missing from our records as archaeologists, even more general information about human remains and osteology would benefit visitors. All in all I felt like this lack of information translated to a lack of “respect” for these people as individuals, and that they were seen as artefacts only.

Panel 34: The jigsaw

(Sorry for the image with me in the background.. I guess we can say I’m a treasure?)

The final panel is a neat conclusion to the exhibit, displaying modern and medieval artefacts which were found in the excavation such as coins and pottery which got there through ploughing, and captions this with the story of how the site was uncovered by workmen in 1960. Finally the last image of the exhibition is comprised of images of trenches, finds, archaeologists and analysis overlaid with a jigsaw which is a beautiful and emotive image. This choice to focus on archaeology and archaeologists as well as Roman history is masterfully played out, integrating the modern process of excavation neatly with the archaeology itself.

Image with a jigsaw overlay of archaeologists working on different aspects of the Fishbourne excavations

The Mosaics

Cupid on a dolphin mosaic

Walking around the bridges to see the mosaic floor was by far my favourite part. It was amazing to see the beautiful mosaics, each one different, laid out as though in the villa. The open layout of the room gave an immense sense of space and a feeling of awe, which is a key part of engagement at any heritage site. It is also almost entirely flat or ramped sections, making the exhibit one continuous experience.

My grandma looking at the mosaics

Practically, each mosaic is separated and labelled in a numbered sequence, meaning that you can walk around the room in a loop following the trail and and back at the start, although the route is not necessarily fixed. Each information board is located where you can see both it and the mosaic at the same time, with a description of the art style or purpose of the room and a reconstructed diagram of the art. Of course, at a basic level it is very important to be able to see both the information & diagrams and the mosaic at the same time to be able to understand and compare the information to reality and encourage learning and critical thought.

A shell mosaic

Something which I only spotted on my second visit was “the digital palace”, an amazing model which lets the user explore a reconstructed villa, clicking to walk into different rooms and looking around in 3d using the mouse. This was on understated computer desk in the middle of the exhibition which the user had to sit down to use, hopefully the museum will be able to find a way to make this technology easier to access for everybody to see and enjoy on a bigger screen!

The computer desk with “the digital palace” on the screen

Computer screen showing a digital model of a roman room, it says “Room N1, Hypocaust Room

Information and instructions about The Digital Palace; a representation of the North Wing made by Anthony Crew.

At the far end of the room there is a viewing platform displaying a slideshow of old and funny images of the archaeological process, and the options of three films called “1960s excavations”, “New Discoveries” and “Mosaic Care”. The use of audio and video technology allows a different way of presenting the archaeology than in the rest of the exhibit which gives the audience a different way to learn that appeals to them most, not to mention being very valuable for visually impaired or hearing impaired visitors. My only concern was that there were no chairs, meaning that visitors must stand to watch the films, which can be difficult or offputting- I also found the soundscapes coming from the viewing platform to be a bit odd.

The Hadley Trust viewing platform showing Barry Cunliffe working on the Medusa mosaic

Garden

The garden didn’t engage me as much but my grandmother loved it; she said she enjoyed the “colourful part with flowers and the pretty green shaped hedges”. It can be difficult for people without an interest in history to engage with museums, but the way the garden was portrayed clearly made an impact on her and she said that she would be happy to revisit based on that. It was designed to look like the grand garden of a Roman villa, with a beautiful scented lavender bed funded by the friends of Fishbourne Roman palace.

View of the gardens; a big grassy space surrounded by hedges laid out in angular patters.

The best part of the garden for me was the themed Roman flower beds. I thought it was an incredibly creative idea, with each flower bed representing a different theme, including medicine, herbs, beauty and all sorts. It smelled and looked incredible and that sensory experience made all the difference to me in enjoying the garden. I’m not sure if my grandma noticed the themes but she loved the flower beds in the same way as I did, noticing the strong scents and bright colours.

A flowerbed with a panel which says “medicinal plants”

Collections Discovery Centre

This building is separate to the museum, opened by Tony Robinson on Time Team in 2007, allows visitors to see artefacts in a more peaceful and very well lit modern area separate to the main museum. There are interactive drawers where visitors can open them to see collections of pottery, glass, bone and more and curated displays behind windows. Visitors are able to look through the window displays and see the store room and scientific research room, adding a new depth to the museum which isn’t just about the Roman history but also the archaeological process and storage of artefacts, which Fishbourne highlights very well.

A window into the conservation laboratory

Artefacts in drawers which visitors can open.

Artefacts in drawers which visitors can open.

A window into the conservation laboratory

The Sensitive Store is behind a window display, which displays a variety of artefacts

All in all our visit to Fishbourne was very enjoyable, and I was inspired by the way in which they portrayed Roman history and culture to a modern audience. I’ll be posting soon about their “hands on” area, which was an incredible way of engaging all ages and types of audience in hands on activities related to archaeologists and archaeology. Following that I’ll be using this research to construct a theoretical plan of how we could portray Malton as a site if we were to have a visitor centre or museum, so stay in touch and make sure you subscribe to email notifications!

Let me know what you think in the comments or tweet me @EdgyTrowel!

This article was written by myself with help from Chloe Rushworth, you can check out her heritage blog and posts about the Malton dig here: https://archloology.wordpress.com/. Photos by myself and my Grandmother.

I visited Fishbourne Roman Palace: Here's my review on how they engage their audience... This week I had the opportunity to visit Fishbourne Roman Palace, and was very excited to see how they portray a Roman site to the public and engage their visitors.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction to Malton

It’s day 4 at Malton and I’m currently sitting by the trench to upload this because my hands hurt.

Below I’ve inserted an audio post, which is a clip of me talking about the site while I trowel.

(Hopefully a transcript is coming soon, definitely let me know if you’re interested and I will hurry myself up)

Key photos

This is my…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This post was inspired by a discussion started by a page I follow on Facebook. They asked what people thought about graffiti on historical buildings, and whether it should be accepted as an archaeological process or whether those responsible should be punished.

To begin, I believe that graffiti is vandalism, it is a crime and I am fully against the act, especially at heritage sites and doubly religious sites. However, I’m fascinated by graffiti at heritage sites as an anthropological phenomenon, humans have always felt the need to make their mark.

As a kid going to Battle Abbey, there was one room behind a corner which was full of graffiti, mostly early 2000s but a lot from the mid 1900s if my memory is correct. It was amazing, so many people had been through there and written their names, the date, or about their relationship. I felt very much the same at Ely Cathedral, an even more grand site but still with a single wall filled with graffiti. Is it okay because someone has already written there? Is it okay because it’s only one wall? And further to that is is insensitive to heritage, to culture or to religion?

Graffiti at Ely Cathedral

Graffiti at Ely Cathedral

Graffiti at Ely Cathedral

Graffiti at Ely Cathedral

One of my favourite examples of archaeological graffiti is in St Mary’s Church, Battle. There is a singular crusader cross carved into a pillar in St Catherine’s Chapel. This was done as a tribute to God, a crusader asking for protection before leaving for the holy land. I think it’s incredible the personal narrative this adds to the heritage site- maybe this is a counter to my point that graffiti could be insensitive to religion, it is instead a prayer, a pledge.

Medieval crosses carved into a column at St Mary’s Church, Battle

Honestly even when doing exams in school the desks had dates back to “2008” carved into them, I thought that was pretty cool, it showed just how many people had been in that position using that desk. (Is that weird? Or just some attention to detail.. I suppose you can’t judge me for getting bored during an exam.)

In the loft of King’s Manor, York, there is a beam with “1960” written into it. Now that’s weird, the manor was used as a school for the blind until 1958 then acquired by York City Council before being leased to the university. Who got into the loft in the meantime?

Also at King’s Manor there is graffiti in the Huntingdon room, which is now used as a conference room, where schoolgirls from as far back as 1745 had etched words into the windows, their names mostly, but also heartwarming sentiments of love towards their friends and teachers. Personally, I think that these sorts of stories are much more incredible than the physical remains, but buildings archaeologists may disagree.

Graffiti in the windows of King’s Manor. (Source)

The graffiti at Kenilworth Castle is beautiful, featuring dates from 1760 to 1950 (so at least they did that to be kind to future archaeologists). I saw it suggested that maybe this graffiti is so much nicer because when it was made, the act wasn’t illegal- it didn’t have to be a quick “i woz ere”, it could actually be art.

Graffiti at Kenilworth Castle. (Source)

Although I have been reminded of the graffiti at pompeii that says “I had sex with a girl by this wall” etc. Is this appropriate? Bit explicit, but it’s amazing now, it’s a real story of the actions of a person, not just physical remains.

“Persons anxious to write their names will please do so on this stone only” at Durlston Country Park. (Image credit Alix Lucas)

It’s a complicated issue, and like I say, graffiti is a crime, but equally it’s a fascinating study, and it gives a personal narrative to heritage that might not be so prevalent without it.

Discussion: Heritage Graffiti This post was inspired by a discussion started by a page I follow on Facebook. They asked what people thought about graffiti on historical buildings, and whether it should be accepted as an archaeological process or whether those responsible should be punished.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

About Me: An Update

About Me: An Update

It’s the start of my third term at the University of York, and it’s safe to say the last six months have been an incredible time.

I’ve been able to study incredible modules with incredible people, so much so that I can’t even begin to think of what to give as an example!! I’ve loved studying the history and theory of archaeology, learning about the development of prehistoric society and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

3 Things to Look Forward to About Archaeology at York

3 Things to Look Forward to About Archaeology at York

Oh, how difficult it is to condense my favourite things into three favourites. I’ve been in York for a few weeks now and I’m three days into my course. In our first term as archaeology undergraduates, we take three modules; Accessing Archaeology, Field Archaeology, and Prehistory to the Present, all of which are a fascinating introduction to the subject, I’m particularly excited to get stuck in…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This is winter, this is night, small love–”

— Sylvia Plath, excerpt from “By Candelight” from Winter Trees

133 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Terracotta lekythos (oil flask) by Painter of Munich 2335, Greek and Roman Art

Rogers Fund, 1909 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY Medium: Terracotta

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248182

38 notes

·

View notes

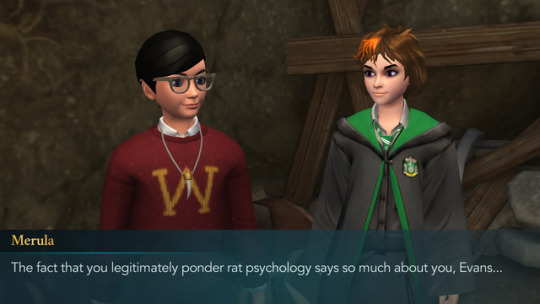

Photo

Yes me questioning a rat would be weird except for the fact that: A. He’s not a rat

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The world is changed by your example.. https://ift.tt/2wg2N1n

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

don’t forget to reblog/like. feel free to send us a suggestion.

831 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Motivational/positive/good vibes lockscreens

Source: Pinterest

Follow my blog for more posts like this :)

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

It’s not who you are that holds you back, it’s who you think you’re not.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

The flooding of Doggerland was the original Brexit.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Mug shot of the Venus de Brassempouy – what’s left of a 25,000 year old ivory figurine from the Upper Palaeolithic. A goddess? The portrait of a living woman – or man?

15 notes

·

View notes