Elizabeth Yin: Co-founder, General Partner at Hustle Fund. Former Partner at 500 Startups. Prev co-founded LaunchBit (acq 2014). Ex-Googler. Coder/marketer from the Bay Area.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Should you raise money or bootstrap?

Should you raise money or bootstrap? (By bootstrap, I actually mean raise < $250k from individuals / angels).

Having run a startup that raised money and now in running a VC, ironically, if I were starting a product company today, I would start out with the mentality of bootstrapping for as long as I could. And, maybe, just maybe, I might consider raising more money under a few limited circumstances.

I would raise more than $250k if I had a company that:

1) Was growing 30%+ MoM in sales and my operations could not keep up to fulfill those sales

I've noticed for operationally-heavier companies (i.e. not SaaS businesses but generally tech enabled services or alike), it can be easy to grow your sales quickly, but often these companies need to throttle their growth, because they do not have enough people to fulfill these services.

2) Was a marketplace with high engagement

Marketplaces tend to be "winner take all" businesses, because they are only valuable if both the supply and demand sides are both liquid and efficient. And, this happens when you have a lot of supply and demand, which means to really thrive, you need to be willing to invest in a land-grab on both sides.

This is why you see companies like Bird, Lime, et al raise so much money. They need to saturate cities with scooters and with users. (basically buy you as a user) In some sense, their businesses are “easier” on the supply side than the current ride-sharing market, because they can manufacture more scooters and don’t rely on people to drive them. They can create infinite supply. In the ride-sharing market, supply is basically a zero-sum game. I.e. someone who is driving for Uber right this moment cannot be driving for Lyft or a food delivering company or what not. That person’s time is occupied. The ride-sharing market will change over time with self-driving cars, and that will also become a marketplace with infinite supply which is easier than trying to grab two sides of a market. But you still need tons of money to manufacture a lot of vehicles.

3) Was growing net revenue 30% MoM for many consecutive quarters where I felt confident to really pour big money in marketing channels

If your business gets past a certain threshold -- call it past the $2m runrate (series A territory), and you are still growing at a fast clip using a repeatable marketing channel or two that works, then it likely makes sense to step on the gas.

The caveat is that many companies have a difficult time crossing the $10m runrate -- this is very difficult to do (series B territory). So you are taking a gamble that with more cash, you can get to series B metrics. It’s just really hard to keep growing 30% MoM with large revenue numbers. But also, running a company at that level involves a large team, and it's tough to manage a larger team. But despite those risks, I would still raise money in this circumstance too.

So what are good bootstrappable companies?

I think the perfect profile of a boostrappable company is a SaaS company. There are often little to no network effects, so your competitors affect you less. I.e. company A using product X doesn't affect company B's decision to use it *most of the time* AND company B being on the platform has no affect on the user experience or value that company A gets out of product X. There are low operational costs -- software has high margins, so you can often pour profits back into the business to keep growing (at least to a good level).

I also think events businesses are good bootstrappable businesses. VCs don’t like to invest in these, so it would likely be impossible to raise VC money at any point in time with this type of company. But, as I've mentioned that events businesses can actually have really low operational costs despite what most people think. If you can get the venue / food / staff / content all free, then the costs are just marketing and your own salary. And on the revenue side, you get your money upfront when people buy tickets or sponsors send you money ahead of the event. And you can often pay vendors on a net 30 basis. So you get money upfront and pay costs later in most cases. People often cite scaling as a stumbling block, but if you look at the truly efficient events companies -- Web Summit comes to mind -- they basically just print money and have a scaled playbook to be able to do events all around the world.

We have a lot of Shin Ramen in our office as a micro VC too.

I think people often equate bootstrapping with low growth or “lifestyle” businesses (which somehow investors seem to equate with “no money” but not always true). But, I think that's false. With the right conditions, bootstrapped companies can be super high growth, high revenue companies. It’s actually not true that you need VC money to grow really fast. With high margin and low cost businesses, you can grow really fast without much or any external funding. And at the end of the road, you can decide what exit you want to take (if even). You have control over your own destiny in a way that most VC backed companies cannot.

I also think people think raising VC money is sexy. It’s like a stamp of approval. But the truth is, VCs are wrong most of the time! Most of their startups end up failing. And the flip side is that there are a lot of great businesses that don’t need VC money to grow really quickly (for all the reasons mentioned above).

I think ultimately, very often entrepreneurs end up raising money for the wrong reasons or raise money too early. They think life will be easier if they raise money - the salary would be better and having more help would be better and pouring more money into marketing would be better. On the surface, I'd say that all of this seems better -- of course we all want more money! But unless you have found fast growth channels, your people and marketing dollars end up not being put to very efficient use, and you are actually no better off than if you had bootstrapped your company but you have given away more of your cap table.

So from seeing things as both an entrepreneur who has raised money before and now being a funder of many startups, this is what I would do if I were starting a product company today.

Fundraising is a nebulous process that I aim to make more transparent. To learn more secrets and tips, subscribe to my newsletter.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A dumb American’s perspective on investing in Southeast Asia

We recently announced at Hustle Fund that we will start investing in Southeast Asian software startups, and my new business partner Shiyan Koh, who just moved back home to Singapore, will be leading the charge on that.

I was in Singapore last week, and I was blown away by the amazing opportunities that Southeast Asian entrepreneurs have ahead of them. It’s one thing to hear from other people that Southeast Asia (SEA) is up-and-coming, but it was totally another thing to go there and talk with so many people about the future.

I haven’t seen this movie yet, but it’s not (entirely) quite like this.

Here are a few thoughts that come to mind from just my short trip there. I’d be curious what other people in-region think about this (and keep in mind, I won’t be doing the investing there, Shiyan will be :) ):

1) There are opportunities galore

People like to use chronological analogies, so if I had to do that here, I would put investment opportunities in SEA at around 1997. To add some context here, I loved learning about all the low-hanging fruit investment opportunities there are.

Basic infrastructure is just being tackled and getting strong traction right now. For example: payments via Grab and others such as AliPay coming into the region. Basic marketplaces like Carousell are big / getting big but there are plenty of opportunities for “large niche marketplace” plays to emerge.

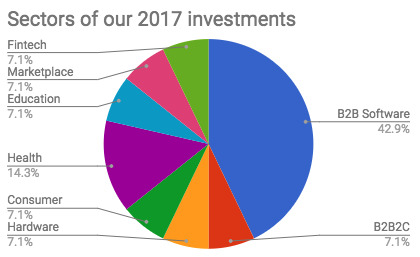

In this first inning of software companies in SEA, major consumer businesses have started taking off, but so many other categories are just starting to emerge. B2B, for example, hasn’t even even really started as a category yet. (more on this below). Health is another area that has a lot of low-hanging fruit opportunities and in some countries is less regulated than in the US (for better or worse). Fintech, too, has many areas that have not yet been tackled -- payments for the banked population is just the first step. This really resembles the era when in Silicon Valley we had Yahoo, EBay, and Craigslist. PayPal was not around yet but ideas were starting in payments.

I think if I were an entrepreneur who was location-agnostic, I would definitely move to Singapore and start a business there. I can think about 20 clearly big low-hanging fruit opportunities in Southeast Asia that would be great to go after, but in contrast, in the US, it’s really difficult to even think about 1 clearly big opportunity. Obviously, the US still has plenty of big opportunities ahead of it -- more on that below -- but the low-hanging fruit around “infrastructure” has been established. Messaging / email generally works. CRMs / marketing tech generally work. Ads generally work. Marketplaces generally work. Payments work. Etc. People in the US can pay for things electronically and can get most services and goods today from the internet -- things in the US generally work, so improvements in these areas are all incremental. Entrepreneurs can still make money improving these areas, but infrastructure improvements in the US are incremental in contrast to SEA which are right now binary opportunities.

2) Building for Southeast Asia is less about tech and more about hustle

All of the above said, because infrastructure takes a lot of pure brute force and hustle to drive adoption, the kinds of entrepreneurs who will thrive in this type of ecosystem are those with a lot of hustle and strong business mindset. All the low hanging fruit opportunities that I mention above are not tech revolutions -- they are all about customer adoption. In many cases, the tech required to execute these businesses have been done elsewhere. (Payments / marketplaces / etc).

Customer adoption is always hard wherever you go. But it’s arguably even harder in a place where there aren’t ready distribution channels. The interesting thing about the US market is that customer acquisition these days is actually fairly straightforward online now for most customer audiences. You can build a SaaS company and get to $1m ARR fairly easily while 10 years ago this was very difficult to do. This is because we now have the infrastructure to be able to look up decision makers on LinkedIn or elsewhere and find online-means to reach people, etc. In SEA, there are some pieces of infrastructure that have been established and exceed the US. Mobile penetration in SEA is much higher than in the US (on a volume basis). This makes it easier to do customer acquisition for a consumer-based company. But for B2B, for example, decision makers for older businesses can’t be found easily online. In other examples, if you’re selling to unbanked populations, not only is the customer acquisition hard, but you also have to operationally do things like collect cash, which US startups don’t have to worry about.

I think this explains why we tend to see consumer businesses emerge first -- tech-savvy internet users are easiest to reach. Other customer audiences are laggards in adopting the internet. Startups formed to serve them need to wait until they come online so that the customer acquisition can be faster.

3) B2B requires selling to other startups

This brings me to my next point. Throughout my trip, lots of people (investors / startup ecosystem builders / entrepreneurs) told me that they are puzzled why B2B hasn’t taken off yet, and that seems to be the next opportunity.

Here’s my take on B2B -- if you look at the US ecosystem, most of the high flying B2B companies got to their level of growth because of fast sales cycles. These fast sales cycles tend to come from selling to other startups. Slack / Stripe / Mixpanel / Gusto et al grew by selling to software startups. The accounts start small but increase quickly when some of your startup customers become big within 5 years. I noticed this with my startup LaunchBit -- we started by selling to startups too, and within a few years, those startups who found success both with us and just in general, grew their accounts with us considerably.

In Southeast Asia, if you are starting a B2B company right now, you will likely need to be selling to older / slower-moving industries. And that sales cycle can be long. But, in 3-5 years or so, if there are a lot of startups that emerge in the ecosystem, then the B2B sales cycle selling to SEA startups will be fast. Here’s a concrete example: we met with a health company based in Thailand who flew to Singapore to pitch investors. They showed us how they were communicating with their consumer customers -- all through LINE messenger. There were literally hundreds of threads of conversations in LINE. At some point, as the startup grows, those conversations are going to become a real pain to keep track of. Can you imagine doing all your business in LINE? (I fully realize that a lot of people do all their business in WeChat in China, etc). You can imagine that at some point, there will be new marketing automation companies that will start building marketing communication software to allow companies to communicate in a more organized manner en masse via LINE to their customers. However, this will only become a big opportunity if there are lots of startups using LINE. So, I think we are probably 3-5 years out for large B2B opportunities to emerge, because first a lot of startups need to get started.

That said, we are definitely interested in looking at these types of opportunities even as early as now, because they take time to build. :)

4) Southeast Asia is fragmented

It’s fun to just lump every SEA country together, but the reality is that SEA is quite fragmented in a way that the US is not. (i.e. language / culture / regulations / etc -- though sometimes the US seems quite fragmented - hah).

I think it’s great if startups have large ambitious of serving audiences globally, but it’s really important to tackle one market first well.

The market that everyone seems to hone in on is Indonesia. Indonesia has 250m+ people, so it’s close to the size of the US. But it’s important to further segment. If you’re trying to go after a banked population that has disposable income, then the addressable segment is probably more like 100m people. This is still a really large market, though.

But, once you start talking about population numbers closer to 100m people, then other countries start to rival Indonesia in size. Vietnam, for example, has strong tech adoption and has nearly 100m people. Thailand has nearly 70m people.

From our perspective, I think while it’s important to be cognizant of market size (for example, Singapore has ~5m people but is a great hub for building a business even if not a large addressable market on the island itself), I met a lot of people who were overthinking the SEA market landscape. As a startup, focus is super important, and nailing your product / service for 1 market of 5m people or 50m people is already really hard to do. And that 1 market -- whatever it is -- should be the focus before trying to dabble in many markets that all have completely different languages, culture, and regulations.

However, this seems counter to the advice that many entrepreneurs seem to receive in the region. If other investors are looking for you to expand to Indonesia even when you’re still tiny, then you may need to think through your strategy on fundraising. I.e. I fully realize that sometimes you have to adjust your plan to make your company more amenable to fundraising, but at the same time, VCs don’t always have the best advice either. And this is a tough balance. So maybe you start with Indonesia if you’re familiar with the market? Or maybe you start conversations with VCs well before you start your company to understand how people think about addressing one market really well before expanding.

Garden by the Bay Mid Autumn Decorations

5) Liquidity opportunities for investors are unclear

Ultimately, as an investor, I think about how eventually a company can get liquidity. And right now, even though some of the markups of high flying SEA companies are good, it’s unclear what the “typical” path of a successful large startup looks like in this region.

In the 90s, in the US, going IPO was a common liquidity path. But after consumers became wary of IPOs, M&A became the much more dominant path, though IPOs are coming back in favor again in some cases.

What this looks like for SEA is unclear and even more unclear is the timeframe. In China, the path to liquidity can be 5 years or fewer. In the US, our darling unicorns often take a decade and sometimes longer to exit. Will large US or Chinese tech companies be purchasing companies for large amounts in SEA? Is that strategic to them? Or will these companies go IPO? And depending on the country, will investors even be able to get their money out once they’ve made money? These are all questions that we have discussed and frankly don’t know the answer to, but the bet we are making is that this will be figured out in the next few years while our investments mature.

6) What are opportunities in saturated markets?

This trip got me thinking about opportunities in saturated markets. In the US, I’d argue that most categories are crowded. Crowded markets aren’t necessarily bad -- it proves demand. And if entrepreneurs can get to a certain level, any exit is good for them. But, for VCs, it’s different. This is where entrepreneur and VC incentives don’t align. A lot of VCs -- especially microVCs like us -- will generally sit out of crowded markets, because they don’t have the capital to pour into their companies to compete to become big winners. And smaller exits are not good for VCs, because they really need their winners to make up for their losers plus return more. We can debate the VC model all day, but that’s another topic for another day.

So in the US, the big opportunities as I see it are:

Products / software for unserved consumer populations along the lines of gender / race / ethnicity -- fashion tech, for example, is an area that has been long ignored

“Super high tech” that alters how we live life dramatically -- think flying cars and everything that Elon Musk dreams up

Providing software to a new generation of tech savvy people in the workplace / consumerizing B2B software for the phone -- for example, every doctor and construction worker today can use technology but 10 years ago, that was not necessarily the case

This means that entrepreneurs need to be more specialized in skillset than in a landscape like SEA. For example, if you are an entrepreneur building a new kind of autonomous vehicle, you really need to have a strong engineering background. On the other hand, if you are building a new kind of ecommerce product for an underserved customer segment, in many cases, you may not need to be technical at all, but you really need to know how to go after your customer persona to be able to out-target more general competitors who are going after a broader segment.

So what this means is that I think we will still continue to see a lot of really interesting technologies emerge from the US as well as even more products and services that will serve just about every consumer and B2B demographic. All of these are all still large opportunities, but I think the ideas that win here will just be much harder to come up with.

Just my $0.02. Would be curious for your thoughts.

Fundraising is a nebulous process that I aim to make more transparent. To learn more secrets and tips, subscribe to my newsletter.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's actually hard to hustle

I should have known that when we picked a company name like Hustle Fund, it would lead entrepreneurs to introduce themselves as “real hustlers”. But, I think my definition of hustle is very nuanced, and it's not what most people think it is.

Very often, most people think of "hustlers" as people who are:

super sales-y

slick talkers / great at talking

doing 100 different things all at once

working really hard and wearing that hard work as a badge of honor

One entrepreneur even told one of my business partners that he didn’t think of himself as a hustler because he wasn’t doing anything illegal! Hah!

But this is not what “hustle” means to me. To me, hustle is about scrappiness to achieve to focus. The key word is focus.

I think the hardest part about running a startup is having focus. Focus is the key thing needed to grow a business. Because you have limited time and money, you can't afford to invest in many different facets of your business. You can usually only afford to do just 1 thing really well otherwise a whole bunch of things will end up turning out mediocre or half-heartedly done - even if you are burning the midnight oil and working really hard.

This is easier said than done, though. What this means in practice is saying no to just about everything. In fact, taking on LESS at a startup in many cases is actually better than taking on more. This means saying no to meetings that will lead nowhere. It means not pursuing partnerships that will only produce incremental returns or revenue. It means simplifying product and reducing features. Ignoring lots of emails. Etc.

As a founder, even with all activities reduced as much as possible, it's still difficult to truly focus, because there are some activities that need to get done in a business that take up a lot of time but don't actually contribute to the growth of your company. Such as reviewing legal paperwork with your counsel. Setting up new accounts and adding 2-factor authentication. Setting up a checking account. Applying for a credit card. Etc. These are all activities that need to get done and take up time that don't actually help your revenue (or whatever your KPI is).

Compounding time management issues, startups also have a lack of resources. E.g. how do you move your lead gen number when you have no marketing budget? Even if you are good at time management and saying no? Being scrappy to achieve focus is just really hard.

My last thought on this is that the good news and the bad news is that being able to successfully hustle is somewhat of a level playing field (though difficult for everyone!). By this I mean, I’ve found that the best hustlers come from all walks of life. People who go to Ivy League schools or worked at Google and Facebook are not necessarily good at hustling (some are and some are not). Often, people from these places actually are given a TON of resources, so scrappiness is not actually something they know how to hone. I went from being a marketer at Google where every news outlet wanted to cover all of our product launches to a bootstrapped 2 person startup where no one cared at all. In addition, people who go to top schools are often very good students. They are often good at being on top of projects and doing everything. Unfortunately, at a startup, you have to deliberately drop the ball on a lot of tasks in order to free up time to really really knock 1 thing out of the park. This is a difficult skill for people who are perfectionists who otherwise excel at non-startup jobs. On the flip side, I’ve also met entrepreneurs who were not good at following directions at school or work, but are able to do incredibly well with their own startups because they have relentless focus on what matters most to the business at the expense of other things.

Working on improving my own hustle is something that I strive for everyday -- since Hustle Fund is a startup in itself, we, too, have a bajillion and one things that we need to take care of but really should only be focused on 1 thing at a time. This means, for example, if we are focused right now on saying helping our portfolio companies, it means that we can’t be responding to everyone who has sent us a pitch deck. This is fine balance, but something I’ve thought about everyday for the last decade or so since embarking on this startup journey.

How do you hustle?

Fundraising is a nebulous process that I aim to make more transparent. To learn more secrets and tips, subscribe to my newsletter.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pre-seed is the new seed

A few months ago, I was talking with a friend of mine who is a successful serial entrepreneur. He has done incredibly well financially on his past two startups, and he's now building his 3rd company. But when we were talking, he expressed frustration in raising his series A round. This was surprising to me. Then I asked him about his metrics, which are good, but they are were not at series A level. And I asked him who he was pitching, and he rattled off a list of usual suspects on Sand Hill. All of those investors told him that he was too early. It turned out he was going after the "wrong" group of investors -- people he would have pitched 3 years ago had all moved downstream now that they had raised much larger funds, and he really needed to be pitching “post-seed” funds.

Every blog post needs a gif of a stuck kitty...

It struck me that a lot has changed about the fundraising landscape in even just the last 3 years. So, I thought it might make sense to take a step back and talk about all the stages of early stage fundraising here in the Silicon Valley.

In early stage investing, at least in Silicon Valley, there are basically 4 stages: pre-seed, seed, post-seed (or pre-A), and series A. In the “old days”, there was only seed and series A and before that, only series A! All of these changes have created a lot of confusion.

Here are my thoughts on these stages:

Pre-seed: this is really the old "seed". Very typically little to no traction is needed at this stage and investors at this stage are looking for lower valuations than seed investors for taking on extra risk by going in so early. Another consideration here is that in the minds of pre-seed investors (who are very often small funds and will be allocating most of their capital in the first round or two), valuation matters a lot more to them than a larger fund who might invest in you at this stage as an option for later. So if a startup comes to me looking for a $3m effective pre-money valuation vs another company who comes to me looking for a $7m effective pre-money valuation, basically what is being suggested here is that the latter company has to have a 2x+ greater exit in order to be just as good of an opportunity as the former. The outcomes of both companies, are of course, unknowable, but that is essentially what goes through the minds of investors who are looking at lots of companies with different valuations.

Also, to be clear, pre-seed doesn't mean that one just thought up an idea yesterday and has done nothing. There's a lot of work to do to prepare to raise money at this pre-seed stage. It could be building an early version of the product. And/or getting your first set of customers. Or even doing pre-sales or lead generation well before having a product. In fintech or health, it could be in dealing with regulations or getting particular approvals even if you’re not able to launch.

Investors at this stage are very much conviction-investors -- meaning they are either bought into you and your thesis or they are not. It’s very difficult to convince an investor at this stage to change his/her mind. This is a bit of a crap shoot, because even if a pre-seed investor is bought into you as an awesome operator, if he/she is not bought into your thesis, it will be difficult to land an investment.

These rounds are typically < $1m in total.

Seed: today’s well-known, seed investors may have previously invested at an earlier stage with smaller checks, but because many of these funds have now raised $100m+ funds, they are now writing much larger checks. Typically this is $500k-$1m as a first check. This means that they have to really believe in you and your business-thesis in order to pour that much capital into a business. As a result, this stage has created a fairly high traction bar. It can be upwards of $10k-$20k per month or more!

Seed rounds today are quite large -- typically $1m-$5m! I believe that some of these seed rounds are way too large, and there’s a looming market correction on the horizon for everyone. I’m of the belief that early ideas can never effectively deploy $4-$5m in a very cost effective way..

Post-seed (pre-A): This is a stage that was created, because the bar for the series A has gone sky high. This really is what the series A used to be. A few years ago, people touted that in order to raise a series A, you needed to hit $1m runrate. Now you typically need a lot more traction to raise a series A round. So, this magical $1m runrate number is now the rough benchmark for the post-seed stage. But, it's not series A investors who are investing at this stage. New microfunds have cropped up to invest at this stage. They are looking for $500k-$1m runrate level of traction. This was my friend’s problem -- he wasn’t quite at series A benchmarks and needed to pitch post-seed investors.

These post-seed rounds are also quite big these days, sometimes upwards of $5m+.

Series A: This is really the old series B round. But Sand Hill VCs who are known for being Series A investors are serving this stage. This is typically a $6-10m round. And companies typically have $2m-$3m revenue runrate at this point.

And if you do the math of VCs buying roughly 20% of a startup, valuations can be upwards in the $50m+ range for today’s series A rounds! On the low end, I haven't seen a valuation of < $20m, and that would be for a really small series A round.

Some additional thoughts:

1) There are lots of caveats around traction.

If you're a notable founder / have pedigree or if you are in a hot space, or if you run your fundraising process really well, it's possible to skip a stage. I've seen some really high flying series A deals happen lately with friends' startups, where they are not quite in series A traction territory, but they have so many investors clamoring for their deal that they can raise a nice big series A round. They've run their fundraising process well, and they generally have great resumes and are in interesting spaces. Same with the seed round -- if you are notable / have pedigree, you can often raise a large seed round with little to no traction on your startup.

2) Sometimes the line between post-seed and series A is quite blurry but the valuations are very different.

I have a few founders I’ve backed who are just on the border of post-seed / series A metrics and are able to get term sheets from both series A and post-seed investors. And there's a huge difference in valuation. The post-seed deals tend to be $10m-$20m effective pre-money valuation, and the series A deals are at least $20m+ pre-money if not much much higher. So, if you're on the border, running a solid fundraising process is especially important in affecting your valuation.

3) Large Sand Hill VCs are doing seed again -- selectively.

Sand Hill VCs who tend to invest at the later stages have now found the series B to be too competitive to win. So they are now starting to do series A deals and seed deals to get into companies earlier. In many cases, these deals they are doing at seed are large deals with little to no traction.

You may wonder “Doesn’t this contradict what you just wrote about?” What’s really happening is that the world of early stage investing is becoming bifurcated -- if you have pedigree and are perceived to be an exceptional high signal deal, you can raise a lot of money without much of anything. These are the deals you read about in the news that make people think fundraising is so easy. “Ex-Google product executive raises $4m seed round.” This goes back to point #1.

If you don’t have that pedigree, then you basically need traction to prove out your execution abilities at the seed, post-seed, and series A levels.

4) Lastly, with the definition of "seed" expanding, more fundraising is done on convertible notes or convertible securities.

I'm now seeing more rounds get done with convertible notes and securities for much longer. This is actually good for founders, because it means you have a much larger investor pool to tap. In the "old days", if you couldn't raise a Series A from the say the 20-50 Sand Hill VCs out there, you were dead in the water. Now, you have a lot more flexibility to raise from angels and microfunds without a formal equity round coming together. I think this is a really good thing for the ecosystem, because at this stage, it’s still not clear who is a winner based on metrics. So there’s still a lot of pattern matching that happens around who gets funded at these early stages. By the time you get to the series B level, it’s pretty clear who is on a tear and who is not, and that is much more merit-based investing. But short of that, the more angel investors we can bring into the ecosystem of startup investing, the more companies will get a shot to prove themselves.

You may wonder, “Well, are there actually companies that are being overlooked by VCs in earlier rounds who later are able to hit series B metrics and raise a VC-backed series B round?” Having looked at a lot of data around this, the answer is definitely YES! While it’s true that the vast majority of companies who end up raising a series B round from VCs previously had notable institutional VC backers even as far back as their seed rounds, VCs still end up misssing a number of companies at the earlier stages. And these actually go on to do well without them and end up coming out of left field and raising money from late stage VCs.

Fundraising is a nebulous process that I aim to make more transparent. To learn more secrets and tips, subscribe to my newsletter.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why an investor rejection isn't a knock on you

A few years ago, a friend asked me if I could forward an email to Abc VC. I told him that since that Abc VC didn't invest in my company, I wasn't sure if Abc VC thought highly of me.

Now that I sit on the other side of the fence, I realized that my thinking was flawed. In many cases, if a VC declines to invest in your company, it isn't a knock against you (caveat being unless you've acted really rude to him/her and/or his/her team). In most cases, rejections happen well before even meeting a team, so that VC doesn't even know you!!

Here are a few reasons why an investor will reject you that has nothing to do with you.

1) Your idea is undifferentiated

Investors see thousands of businesses a year. And, your idea is 50th social networking site of the week. Unless you have a differentiated angle / approach to the problem AND/OR significant traction, an investor won't be able to understand why you stand out and why to back your horse instead of someone else's. Especially at the early stages.

Note: by differentiation, I'm not talking about product or feature differentiation but outcome differentiation. For example: if you're creating a new Mailchimp competitor, you might think your product is differentiated if let's say your product has better tracking than they do. That's a feature difference. But outcome-differentiation is probably lacking -- people who use Mailchimp use it to increase revenue by selling more products / services via their emails. So unless your feature can increase that outcome -- and not just incrementally by 20% but a serious differential like 10x -- it's unlikely that a current happy Mailchimp customer will want to switch to your product. Think about it -- if you’re using MailChimp and make let’s say $100 in sales for every send. It’s going to be a real pain in the neck to move to a new product -- your whole list is set up and everything for just an additional $20 per send.

Often as an entrepreneur, it's hard to know whether your product is differentiated, because you don't know what other startups are out there. This is something I personally faced when running my company LaunchBit. There were/are so many freakin' ad networks / ad exchanges / ad platforms out there that LaunchBit was just undifferentiated. A business like that will just have a really hard time raising money at the early stages, and if that's feedback you are getting from at least 2 people, you may want to consider adjusting your plan and raise from angels and/or bootstrap for a long time. It doesn’t mean it’s a bad business -- in fact, it could be a very good business for you. It just means VCs will shy away from it.

2) Your idea is not the right fit for stage / industry.

Your idea is not a good fit per the investor's thesis / mandate. Sometimes this can be incredibly difficult to see. For example, a lot of software investors don't invest in e-commerce companies. (We do not.). The products are physical things that cost a lot to store as inventory, and fundamentally, this makes e-commerce companies a very different profile from products that are entirely digital (software / software platforms that don’t house inventory / digital products / etc).

Or, a lot of investors call themselves "early stage" investors and aren't good fits for pre-seed companies. Many of these investors mean "series A" or "post seed" when they say "early stage" even though they will do a handful of pre-seed deals in founders they already know / successful serial entrepreneurs we’ve all heard of.

What I’ve found to be most annoying about the VC industry as an entrepreneur is that you can never pin VCs down in what they like. This is because VCs are always hedging to be able to see everything just in case there is that rare exception that they would potentially invest in something outside of their thesis. The best way to assess what VCs actually like is to look at their portfolio. If a VC says that they invest without traction, you should find out when they’ve done so and whether it's because they already had deep relationships with that team / that team has incredible pedigree. And just play the probabilities in your head of who will actually be likely to invest in a random company at your stage.

3) Your business model seems flawed OR is not the right fit

I talked a lot about unit economics and sales cycles in my last post. For me, I personally think very heavily about the unit economics of a business, and if I can't get conviction around the potential customer acquisition, that's an immediate pass for me regardless of the team / market size / product / etc. I do understand that teams can pivot, but we are already so early in the lifecycle -- often first check into a company -- that I can’t be counting on pivots.

But VCs look at unit economics in different ways. For example, some VCs have such deep pockets that they can throw a lot of money at a company to wait out a long sales cycle. But that's not Hustle Fund. We are currently a small fund. So when we back a company, we need to believe that we can help that company get downstream funding from other investors with deep pockets OR that the company can bootstrap its way to success.

In order to bootstrap your way to success, it largely means you need high margins and fast sales cycles. These are companies that we can get behind as a lone ranger if we see hustle, focus, and a differentiated solution.

But, if you're in a category where you have a long sales cycle or smaller margins, then I need to think about if I can "sell" your deal to other investors -- either people who will invest alongside us or after us. We talk with and do try to understand what a lot of our early stage investor peers are interested in to help inform our decision. But the point is, when we are looking at companies with these type of customer acquisition qualities, we cannot make decisions in isolation. We need to believe other investors will buy into you as well even if we are still first check into your company.

3b) The market size is not big enough

For a VC portfolio to work out, a VC's winners need to compensate for all the losses of the losers plus much more to provide great fund returns. Not only does the fund need to be net profitable, but it also needs to outperform other assets that our would-be backers could be investing in -- such as other VC funds, real estate opportunities, the public stock market, etc.. No one really talks about how VCs differentiate themselves and what they need to deliver to their investors, but this is a big factor in affecting how they invest in companies.

So, for a VC, it's not good enough to have a winner "only return 10x" even though that would be a phenomenal outcome for a founder or even an angel. Most VCs need their winners to return 100x (or ideally more).

This is why it seems that every VC is harping on looking for billion dollar markets. If you are not thinking you have that big of a business, VCs are not going to be the right people to raise from. Angels might be a better fit.

But, for me personally, I think the problem with market-sizing exercises is that you just don't know whether a market is big or not! Airbnb is probably the poster child example of this. At the seed stage, it seemed like a weird niche idea to sleep on someone else's air mattress. What is the market size for this? Basically zero. But sleeping on a bed in someone's house is an alternative to getting a hotel room, and the hotel market is huge. So it's just very difficult to know whether a market size is big or not in the early days, especially for seemingly "weird" ideas.

This is why I don't care to ask founders about their market size. Their predictions will be wrong and so will mine. Moreover, even if a market is big, it doesn't mean the company can grab a lot of that market share. This is why I very much focus on a bottoms-up approach to analyzing a marketing -- looking at unit economics / sales cycles / customer acquisition. If the unit economics and sales cycles are rough, I don't care how big the market is, it's going to be a long difficult slog to capture the market, and that means a very capital intensive business. And then that goes back to the question of whether I think I can round up co-investors with me or downstream investors to fund this.

In short, these are 3 reasons why a VC might reject your business when they haven't even looked at your team or anything else about your company. It doesn't mean you necessarily have a bad business, it just might not be the right fit for that particular firm or the VC industry in general. So in most cases (caveat being if you were rude to someone on our team), when we decline to invest in companies, we would very much welcome seeing a different business that the founder starts later or would be honored if the founder wanted to take the time to refer a friend who is working on a startup.

Fundraising is a nebulous process that I aim to make more transparent. To learn more secrets and tips, subscribe to my newsletter.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The #1 thing successful founders think about for their next startups

At Hustle Fund, we back both first time founders as well as repeat founders. One thing I've noticed is that almost every repeat, previously-successful-founder focuses on the same thing for their respective startups: customer acquisition. These founders not only think about customer acquisition first, but in many cases, they will even:

Abandon a startup idea altogether if the customer acquisition strategy isn't strong

Pre-sell / generate leads well before building a product to try to validate demand

Some thoughts on customer acquisition from my own learnings over the years both as a startup operator and talking with a lot of startups:

1) Unit economics matter A LOT.

Unit economics are something I've found most entrepreneurs (and investors!) don't think about at all. Forget about traction and hockey stick growth. It's hard to get there without ideal unit economics. Very simply, your cost to acquire a customer needs to be lower than the value of that customer (lifetime value).

This is obvious. Diving in a bit more into some thoughts here:

1b) Ad-based revenue streams generally have terrible unit economics.

A typical ad-based revenue stream on a media website is around $5 per 1000 eyeballs ($5m CPM and give or take $1-$20ish CPMs). In other words, if you can get 1000 people to come to your website consistently for under $5, then this business model works for you. But this is incredibly hard to do, and most sites cannot do this at scale. As always, there are exceptions: if you build a viral consumer product (such as an Instagram) where people are just coming to your site / app in droves at no cost to you, then you've got a great business. But, if they are not, it's very hard to use paid acquisition to generate that type of traffic for under $5.

As a result, second time founders very often shy away from ad-based consumer ideas, but when they do, they think about what viral mechanisms you can implement *first* and engineer the product around that mechanism. Marketing first. Product second. Here is a good case study on LinkedIn (scroll down to see how they grew). Or second time founders focus on lucrative verticals that pay more per eyeball or focus on ad formats that pay more (such as email newsletter sponsorships).

Ads can also be cost-per-click or cost-per-action ads. Although you can make more money by running per-click or per-action ads on a per conversion basis, it's also a lot harder to bring about these actions. In particular, one thing to consider if you're trying to make money off affiliate ads is to think about how unique the product/service is in the ads you're running. For example, if you are running affiliate ads for hotels, you might get 3-5% on a sale. So if someone books a hotel at say $100, then that means you make say $5 on that transaction. But if this is a generic hotel, then there are likely other affiliates who are doing paid marketing to try to get users to their sites / apps to convert users as well. Moreover, the hotel itself may be running ads to drive traffic to their site / app, and for them, a conversion is worth far more than $5. So you will likely get outspent on any paid marketing channel you may use to drive traffic to you at scale if there are other people trying to drive traffic to the same property.

Even if you are not scaling with ads, partnerships and SEO also cost money, and your competitors or even complementary companies are all spending money on partnerships and SEO in order to drive as much traffic as they can. One way to make an affiliate-ad based revenue stream work is to have access to unique products that no one else online is trying to sell. This could mean partnering exclusively with someone who makes products offline (and who is not tech savvy to compete online with you).

Another way is to have unique promotion channels, but these must be scalable. Honey, for example, is a browser extension that is always in your browser and helps find coupons for you for any site you browse. This allows them to retain users for a long time and make some affiliate revenue by directing you to particular offers that they get paid for. Or, there are some hardware companies, for example, that make money based on affiliate revenue. They sell their hardware at cost -- say a new refrigerator. And, when you buy food on a recurring basis, then they make recurring revenue by your buying food through their affiliate channel. You will use your fridge for a decade or more so the retention here is high.

There are clearly many companies making money on ads of some sort, so this is not to say that you cannot build a big company with ads. You definitely can and there are many who do. But, remember, the key insight is you need your revenue stream to be much more lucrative than the cost to acquire your customers who generate that revenue.

2) B2B startups have high margins. Sales cycles matter though.

Many serial entrepreneurs tend to gravitate towards building B2B startups. I can't tell you how many founders I know whose first company was a consumer company and then built only B2B companies after that. B2B companies can have great unit economics. Business customers, depending on the problem, are less price sensitive than consumers.

HOWEVER, the length of a sales cycle is a strong consideration for most repeat successful founders. For repeat founders, this can actually work BOTH WAYS.

On one hand, I know some really successful founders actually opt for a *longer sales cycle*. (I use "sales cycle" loosely -- by this I mean the time it takes to get a product paid for, and so this involves both product development and time to get a check from a customer). Some successful founders would prefer to go after a REALLY lucrative revenue opportunity that has a "longer sales cycle", because they can capitalize their company long enough with their own money + friends' money to gain the sale. In some sense, their moat is capital, because most people will not be able to access enough capital (either by raising or by bootstrapping) to go after a similar opportunity. Examples of this include startups that are building a new airplane or a new car or a rocketship or a new power plant, etc... Most first time founders cannot just start bootstrapping a new rocketship startup.

Sales cycle, as a consideration, also works the opposite way. Many repeat successful founders would also actually prefer to go after opportunities with a much shorter sales cycle. So if we use Christoph Janz' animal framework for building a big business for types of customers you can be going after, these founders won't be hunting elephants. But they might go after rabbits or deer business customers.

And, because these companies are often able to move a lot more quickly than elephants, founders can often pre-sell before a product is ready. Or at a minimum, generate a lot of leads before building to generate momentum and start to validate a business opportunity with real people and real money. This pre-sales strategy, of course, can also be used for consumer businesses that sell things.

As a side note: many companies in our portfolio at Hustle Fund, regardless of what they're building, have pre-sold their products before building anything.

3) Does your business have naturally short retention?

Repeat successful founders also think a lot about retention. Some ideas seem like a good ideas but actually are not because of the retention component. (or lack of). Here is an example:

I used to run some wedding-related sites; there's obviously a real need for products and services in the wedding space. And, engaged couples pay a lot for weddings! On the surface, this seems like a good space to be in. But, the retention is terrible / non-existent. Once someone gets married, in many cases, this person won't ever come back and generate revenue (or at least not for a decade later). (Although I did once have a customer who bought from me, then called off the wedding, and then a few months later came back to my site to buy more, because she was now engaged to someone else. But the vast majority of my customers were not in this camp.). This is not to say that you shouldn't do a wedding-related startup, but it's important to think about how to retain a customer to convert him/her towards other things.

The Knot is a great example of a site in the wedding category that tries to retain people. The Knot would not consider themselves a "wedding company". They would consider themselves a "lifestyle company" -- they retain their users by moving their users to "The Nest" and later "The Bump" as you start settling down into married life and then have children. This allows them to make money on their users for a much longer timespan.

Retention applies to B2B companies as well. For example, there are a lot of startups who offer products/services to startups. When their customers outgrow them and become big companies, can they grow with them and offer products that make sense for larger companies? Hubspot is a good example of this. Initially, they focused on SMBs, but today, a lot of enterprise businesses use them. But they still do partnerships with startup organizations/accelerators so that startups can start using their platform and grow up in the Hubspot ecosystem.

So if you are starting a company around a person or a business' stage of life, think about how you can retain your customers / users over time.

4) It's nice when someone else pays for a customer.

This is a very rare customer acquisition situation, but in some cases, a company can jump on an opportunity where a consumer benefits but someone else pays on behalf of the consumer. This is nice, because the consumer gets something for free and is your user/customer. So, the customer acquisition is easy, because this person doesn't need to pay money. And, someone else is footing the bill and must do so. This is a fantastic customer acquisition situation.

This type of scenario often happens in weirdly regulated situations. In health, for example, almost all online pharma startups are in this category. A startup gets a consumer to sign up for service to get his/her medication for free. His/her insurance must pay for it.

This type of inefficiency happens in other industries as well and is something that I personally look for. So, we've backed a couple of companies that fall into this category (they are not all health). The customer acquisition is incredibly fast and high growth (i.e. easy to convert users when something is free to them and that something is awesome).

In summary, when I evaluate startups, a big initial criteria for me is around evaluating how deeply the founders have thought about customer acquisition (and retention) and whether they are customer acquisition-centric founders. This does not mean the founders need to have marketing and sales backgrounds; in fact, most of our founders do not have this background. But, thinking about the unit economics as a business owner BEFORE building your product is incredibly important regardless of your background.

Fundraising is a nebulous process that I aim to make more transparent. To learn more secrets and tips, subscribe to my newsletter.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 Things I've learned from running a micro VC in the last year

It's been about a year since I started working on Hustle Fund with my business partner Eric Bahn. People often ask me what it's like to start a micro VC and whether they should do one too. (Hunter Walk just wrote his perspectives here)

Here are some of my learnings from the last year.

1) It is absolutely the best job in the world for me.

I enjoy learning about new technologies and ideas -- and you get to see a lot of them in this business especially in early stage investing. And I enjoy working with founders immensely. But most importantly, I love fundraising. I know -- that isn't what you thought I was going to say. (more on this later)

Much like running a product-startup, you're your own boss, so you sometimes end up working really hard and at all hours depending on where you are in your fund life cycle. But, if it's work you enjoy, then it doesn't feel like work. And, there's also a lot of flexibility, and I've definitely taken advantage of that. You can whimsically pick the most powdery day of the winter and go up to Tahoe to ski. Or go to the beach or lake mid week in the summer and no one will be there. It's great.

2) Starting a micro VC is just like starting a product company. Except harder.

Probably 10x harder. If you go in knowing that with eyes-wide-open, then it's totally fine, but most people don't do enough homework before deciding to start their funds. I would talk with at least 10 micro VCs before deciding to do this.

3) In particular, there is no money in micro VC!

Hah - this seems ironic, but I'll explain.

Most people think VCs have a lot of money. That's if you work for an existing large established VC. But if you are starting a VC, this is definitely not true. I'll break this down across a few points, but the gist is that you have to be willing to make no money for 5-10 years.

If you are not in a solid financial situation to do that, this business can be terrible for your personal life.

3b) Micro VC's have no budgets.

This is surprising to a lot of people. Even if you have say, a $10m fund, most of that money needs to be used for investing -- not for your livelihood or for other things.

In fact, the standard annual budget that VC funds have is 2% of the fund size for the life of the fund (typically 10 years). If your fund is say $10m, then that means you have a yearly budget of $200k. To be clear, this isn't your salary -- this is your budget to run your company. Your salary does come from this number, but you also need to cover salaries of everyone else on your team (if there are others on your team). And, if you travel, those costs come from this number too. If you have an office, that cost fits in here too. Health care and benefits also fit under this. Marketing -- if you have t-shirts / watches / swag, parties -- all of this fits under this budget. There are also fund ops costs that need to be factored into this number too. As it would turn out when you factor in all these costs, $200k actually doesn't go far. To give you some perspective, my salary today is less than what I made at my first job out of college...in 2004.

You need to be willing to bootstrap for about 5-10 years. In contrast to building a product company, where most people bootstrap for maybe 2-3 years and then either raise some money or build off of profits or throw in the towel, when you sign up to do your own VC, you are committed for 10 years (the standard life of a fund). You can't throw in the towel. And if your fund does well -- i.e. your companies either raise more money or they grow their revenues a lot -- you also don't make more money, because your salary is based on a percentage of your fund size. So your salary (or lack of salary) is stuck for years -- until you raise your next fund when you will have new budget from that fund.

Some Micro VCs write into their legal docs that they will frontload all of their budget in the first few years. Under this model, instead of taking say a $200k budget per year for 10 years, some funds will do something like frontload the budget -- say $400k per year for 5 years. This can help increase your budget, though there are still fund ops costs every year for 10 years, so I'm not sure how these funds end up paying for those costs in years 6-10 if they are taking the full budget up front. This is not something we do at Hustle Fund.

Other micro VCs will try to make money in other ways by selling event tickets or whatnot. In many cases, depending on how your legal docs are written, consulting is discouraged. So it actually is very hard to bootstrap a micro VC, because on one hand, you get virtually no salary but are also mostly prohibited from making money outside of your work.

3c) You also will make General Partner contributions to your fund.

At most funds, you will also invest in your fund as well. This allows you to align with your investors and have skin in the game, and this is standard practice. In many cases, fund managers invest 1-5% of the fund size. So if you have a $10m fund, you'd be expected to invest at least $100k to the fund.

So, not only are you not making money on salary, you are also expected to contribute your own money to the fund.

There are some funds that don't write this requirement into their legal docs, but it's something that a number of would-be investors always ask about (in my experience). They want you as a fund manager to be incentivized to make good investments, because you are staking your own cash too. And this makes sense.

3d) Sometimes you need to loan money to your fund.

There have been several cases over the course of the last year, where either Eric or myself have had to loan Hustle Fund money interest-free to do a deal that needed to be done now (before we had the fund fully together).

One thing that is different about raising money for a fund (vs a product-company) is that when investors sign their commitment, they don't actually send you the money right away. So, let's say we raise $10m, we don't actually have the $10m sitting around in a bank account. This surprises a lot of people -- VCs don't actually have cash on hand!

The way investors invest in a fund is they sign a paper committing to invest in the fund. And then later, when the fund needs money, the fund does a capital call. Typically, capital calls are done over the course of 3 years. So, if let's say an investor commits to investing $300k into a fund, then on average, that fund will call 1/3 of the money each year over the course of 3 years. In this case, that would be roughly a $100k investment each year from this individual. The capital calls are not done on a perfectly regular cadence, because sometimes a fund will need money sooner than later. But most funds try as best as they can to do regular capital calls.

But, this also means that there's a lot of strategy and thinking that needs to go into capital calls. For example, when you're first starting out to raise money and have very little money committed -- say $1m, it can be tempting to call 50% of the money right away to start investing $500k into a couple of deals. However, as you continue to raise, subsequent investors, will be required to catch up to that 50% called amount. And let's say you round up another $6m in capital, this means that all of a sudden you have $3m that you're automatically calling to catch up to the proportionate amount that the first set of investors contributed. And if you're writing small checks out of your fund, much of that $3m will then just sit around in your bank account not earning interest and will negatively affect your rate of return. So instead of doing a capital call, loaning your fund money is a way to ensure that you don't have capital just sitting around in your bank counting against your rate of return.

There are bank loans you can get once you are fully closed and up and running, but very few banks will loan you money in the very beginning when you have raised nothing - hah.

3e) And even if your fund does well, you still make very little money at the end of 10 years!

First, most VC funds are failures. In fact, much like startups, I've heard that 9 in 10 VCs will not even get to 1x returns!

But, if you happen to be in the lucky 10%, there's even a range here. The "gold standard" for profitable VCs is a "3x return" benchmark. If you're above it, you're considered excellent. And this is very hard to do. Just getting into the profitable category is an accomplishment in itself. But, let's suppose for a moment that your fund is excellent (because we all believe that our funds are excellent). And let's say that we return 5x on our fund.

On a $10m fund, a 5x fund return means the fund will return $50m. Using a standard 20% carry formula, and after returning most of the gains to the fund's investors, it means that the team will receive $8m. If you have 2 managing partners, that's $4m per person -- but 10 years later. Considering that you'll make no salary for much of that time, there are many other professional / tech / established VC jobs at big Sand Hill firms that will make you more money or the same amount of money on salary alone (not including benefits or stock) with greater certainty. You don't have to be a 90%+ performer as a Director of Product at Google to accomplish the same outcome as an exceptional micro VC manager. Think about that -- you risk so much, much like a startup, but your upside is equivalent to working a steady job at Google for 10 years!

For all of these reasons, this is why microfund managers who are able to raise more money on subsequent funds end up doing so, because for the same amount of work and risk, you'd much rather be paid more in salary and in carried interest later.

4) You should love fundraising.

I think most people think that as a VC you spend most of your time looking at deals. The breakdown of a given week for me is something like:

50% fundraising-related (preparation of materials / meeting potential future investors / networking / etc)

20% marketing-related (content / speaking / etc)

5% ops (legal / audit / accounting / deal docs / etc)

15% looking at deals (talking w/ co-investors & referrers / emailing with founders / looking at decks / talking with founders)

10% working with portfolio companies

Of course, it varies a bit depending on if you're at the beginning of a raise or if you have closed your fund. But, the point is, you will spend a solid chunk of your time as a micro VC on fundraising activities. Even if your fund is closed and you don't have a deck to pitch, you are always in fundraise-mode.

If you have never fundraised for anything before, you will probably think that this process is horrible. Having raised money before for my startup and having coached a lot founders on fundraising over the last few years, I've grown to love it. And part of that is just lots of practice -- the more you practice, the better you get, the more you like something.

5) Fundraising for a micro vc is exactly like fundraising as a product-startup. Except more involved.

Prior to raising a fund, it never occurred to me where fund managers raise their funds. That was just not something I had thought about before. For the big Sand Hill VCs, most of them raise money from institutionals. These are retirement / pension funds at goverment entities. Or endowments at universities. Etc. But as you can imagine, these entities are pretty conservative. And rightly so, the pension check that granny is counting on for her retirement shouldn't be frivalously thrown away on a fund that invests in virtual hippos recorded on some blockchain.

So as a first time manager, often it can be difficult to convince these types of institutional funds to invest. It can be done if you have a strong brand already. But even if you are an experienced angel investor or worked at a well-known VC fund, you're still starting a new fund with a new brand, and there are still questions about whether you can repeat your past success on this new brand.

This means that much like product-startups, you end up raising from individuals, family offices, and corporates primarily. But much like with raising money from angels and corporates for a product-startup, angels and corporates don't have website announcing that they are funding vc funds. You have to hunt for these folks. Often these "angels" whom you can access are folks you know or folks who are 2-3 degrees away from you whom you don't know yet (see my post on raising from friends and family).

And much like a product-startup, the check sizes are going to be smaller if they are from individuals (unless you know lots of very very wealthy individuals). When we first started fund 1, our minimum check size was $25k -- much like the minimum investment amount for a typical product-startup. Except that we were raising tens of millions of dollars not $1m. So, $25k doesn't go far on say a $10m fund.

This means you need to be doing lots of meetings. And this takes time. The average time for a microfund manager to raise a fund is ~2 years. We felt fortunate and incredibly thankful to our investors to be able to raise our fund in < 1 year. But, when you think about it, that's still months of actively fundraising. (see point #4)

6) And you have a limited number of investors you can accept.

Per SEC rules, you can only accept 99 accredited investors into your fund. This means that if you want to raise a $10m fund, you need the average check size to be above $100k.

When product-startups set a minimum check size, it's usually arbitrary. If you're raising $1m for your product-startup, it won't hurt you to take some investors at $1k or $5k checks here and there, especially if they are value-add. With a fund, every slot counts.

So when we started with $25k as a minimum check size for some friends, we knew we needed to quickly raise that bar in order to raise a significant enough fund and still maintain 99 investors. We ended up having to turn away a lot of great value-add would-be investors who could not do a higher investment. I would have absolutely loved to have brought in more investors if I didn't have this restriction.

In other words, you cannot just accept $5k here and there from friends and claw your way to momentum.

To get around this, some funds set up a “1b” fund. E.g. Hustle Fund 1a and Hustle Fund 1b and split startup investments equally between the two. That would be one way to get bring in more investors, but the costs of this setup start to go up, so we decided not to do this.

7) Ok, so there's no money. You also cannot change the world on fund 1.

If you can get past all of the above, and you're still "yay yay yay -- I want a life of making no money and want to fundraise all day and night for whatever cause I am trying to support," the last piece is that you should know that you cannot change the world overnight.

I know so many aspiring micro VCs who go into this, because they want to fund more women or minorities or geographies or some vertical that is underfunded. And I think those are all awesome worthy causes. And me too -- the reason I'm doing this is that I don't believe the early stage fundraising landscape is a meritocracy, and I want the future of funding to be much more about speed of execution rather than about what you look like or how you talk.

But you absolutely need to go into this with a 20-30 year plan. And the reason is that you're a small little microfund with say $5m, you won't be able to change the numbers in any of these demographics, because impact happens at the late stages when VCs pour tens of millions of dollars into companies -- not $100k here and there. What does effect change is having lots of money under management. And that happens by knocking fund 1 out of the park. And then fund 2. And then fund 3. And growing your fund each step of the way. And growing your believers who start to hop onboard your strategy -- not only your investor base but other VCs. And that is a 20+ year plan.

Moreover, you need to be contrarian to have a good fund. But at the same time, you cannot be too contrarian either on fund 1, because you need to work with other VCs in the ecosystem. You need your founders to get downstream capital. So to a good extent, I do care a lot about what downstream investors think and how they think about things. You can only start to be very contrarian once you have more money under management (i.e. have proven out the last couple of funds) and follow on into your companies yourself.

So in short, you will not make any money on fund 1. You might need to loan money to your fund. You will need to have money to invest into your fund. You will constantly be selling your fund as an awesome investment opportunity for this fund and the next fund and the fund after that, etc... And you will not change the world on fund 1. But, if you still love all of this and go in with eyes-wide-open on all of these things, and if you believe you want to do this for the next 20-30 years, then I would highly encourage you to go for it. I think it is the best job in the world.

Fundraising is a nebulous process that I aim to make more transparent. To learn more secrets and tips, subscribe to my newsletter.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to raise money from friends and family

Most VCs won't invest in startups super early. There are some exceptions -- my company Hustle Fund tends to invest quite early, and so do a few of our peer funds at the pre-seed level. But, there are only a handful of us, and 99%+ of startups won’t be able to raise money at this stage. Alternatively, if you are a successful entrepreneur or have great connections, multi-stage VC funds will also invest super early in these types of founders.

But for the vast majority of entrepreneurs, doing a friends and family round of funding during the earliest stages of a company is the primary way to raise money. I know for many people, raising from friends and family doesn't come naturally. Many entrepreneurs may feel like they don't know enough rich people to raise money from their network. Many people -- would be investors -- you ask to invest may also feel like investing is only for the really rich. It can also be confusing and awkward to ask people close to you to invest. How do you even broach the topic? Will the person be taken aback? Will it ruin your relationship?

Here are some tactical tips from my personal experience that might be helpful:

1) Dedicate lots of time to fundraising.

Fundraising, in general, takes a lot of time. And, raising from friends and family is no different. As I've written about previously, one of the biggest challenges in fundraising is that it just takes so much time to balance running a company and raising money.

2) Set up "catch-up" meetings with friends and family.

It's really hard to know who will be interested in investing in your new venture. Set up "catch-up" meetings with everyone who is smart, has means, and/or is well-connected. In each of these meetings, you'll certainly "pitch" your new venture, but you are not necessarily looking to raise money from each of the people you meet with. In some cases, you may only be looking to get introduced to more people who may be good to meet with.

Pack these meetings into a limited period of time to maximize FOMO as well as maximize the efficiency of your fundraise.

3) Be creative about your meetings.

Your meetings could be coffee catch-ups. But in other cases, maybe you cook brunch at your home and invite people over. Or maybe you invite a lot of people over at the same time. In other cases yet, you may want to do a group social activity -- it could even be bowling. Whatever works for you and what you think your friends / friends-of-friends / family may like doing to make your meeting less formal.

Your meetings don't have to be stiff coffee meetings.

4) You are always "pitching" even if not formally.

You should have a deck ready to show on your phone or computer but you don't always need to use it. I find that at the earliest stages, people are mostly investing in you.

Make sure that at some point in all your catch-up meetings you mention:

You are starting a new company

One line about why it will change the world -- think very high level here.

That you are raising money for the company

That you are raising only from friends and family

Casually ask if he/she would like to invest or if he/she knows 1-2 people who might be interested in potentially investing or may know other potential investors

It is important to get each person you talk with very excited about your business. I find that one of the biggest mistakes entrepreneurs make in pitching their high level ideas is that they say too much about what their product idea does. E.g. "I'm starting a new social network that will combine Facebook, Snap, Instagram, WhatsApp, WeChat, and LINE all in one place." or "I'm starting a new AirBnB for retired people." This isn't very exciting. The only person excited about your product mechanics is you. BUT, you can get people excited about outcomes. "E.g. I'm building a new social network that will bring people globally closer together -- so that people in India can talk with people from Japan." or "I'm starting a new type of housing platform so that older people don't need to live in stodgy sad retirement homes and can live a vibrant independent life."

When pitching to people who do not invest for a living (i.e. non fund managers), it's important to explicitly mention that you are raising money and that you want their help. This could mean that they could help introduce you to other people and/or that they could invest.

There are a lot of people on the internet who say you should ask for advice and not money. IMO, this is really awful advice. Most people who do not invest for a living -- even active angels -- don't realize they are being asked to consider your idea as an investment if you don't ask for their help in raising money. If you are talking with your dentist about your new startup, his/her first thought is not, "Oh I wonder if I can invest?" or even, "I would never invest in this." His/her first thought will be, "Oh cool, John/Jane Doe has a new career. I'm going to make a mental note that he/she has left Cisco and is now working for himself/herself." They don't see themselves as investors, and so you need to explicitly make the ask if you want an investment. You cannot just assume that people will volunteer to invest.

So your conversation might end up going something like this:

"So yeah, lots of new changes. I left Cisco, and I'm now starting a company. We are trying to do ABC in the world, and if we're successful, DEF will happen. Right now I'm raising some money from friends and family to achieve XYZ goals. I wanted to see if you might be interested in potentially investing or know 1-2 individuals who might be interested and good to talk with?"

(Please don't monologue. But, those are the rough talking points that you need to bring up.)

At this point in the conversation, you are making the ask only to see if the person will consider investing. (Or knows someone who might be good to talk with). You are not asking for a commitment.

It is important to mention that you are raising money from friends and family. A lot of people have in their heads that entrepreneurs raise money from funds and don't realize that at the earliest stages friends and family have the opportunity to invest in your company and also get the best deal. This is what you need to educate would-be investors on.