heretofangirl

1K posts

lumi ₊˚⊹♡ multifandom ₊˚⊹♡ she/her ₊˚⊹♡ 20

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

foliage study :-) there's an angel in the garden

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

* Knowing that eventually a ghastling will be happy fills you with determination

These silly thangs made my week dude. I used to hate them but lowkey now I feel bad. Mojang giving out update bangers makes me happy.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

I think this has been posted on here before but this one always makes me laugh

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm sure this has been talked about plenty but I'm still awestruck at how well Frieren handles Himmel and Frieren's relationship. I have never seen the 'character haunts the narrative' story beat done to such effectiveness.

Frieren's regret is that she didn't know Himmel before he was gone- but he exists in everything Frieren does without her fully realizing it. Frieren is a fundamentally different person and we *know* it is mostly thanks to Himmel's influence. The constant flashbacks, the way in which Frieren's logic and everyday routines have been altered by his memory. She collect spells because he and the others complimented the mundane, random spells she had found. The way that instead of her master, Himmel is the person who the monsters choose to immitate.

The flashbacks too, are so so potent in characterizing who Himmel was- not only in regards to Frieren, but in regards to Himmel as the hero. The person who lead his group to kill the demon king. The person who did everything in his power to help those around him. The person who was so clearly in love with Frieren but understood intimately that Frieren would not love him in the same regard and even worse, would be walking a very long and lonely path.

Hell, it's at the start of every chapter, in which time is only kept by the years before and after Himmel's death.

It all comes back to him, in the end

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Snow ending his book with the line “snow lands on top” really set the tone for the rest of his life. As a loser. Especially in contrast to the heartfelt last lines of Katniss and Haymitch’s books. Wtf is “snow lands on top”. Do you think this is Twitter.

#tbosas#he’s such a loser god#I need to psycho analyze him and then throw him against the wall#like one of those sticky toys you get from carnivals

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm nobody's idea of a hero, Haymitch.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

I dont understand how people think “but they killed people!” Is everrrr going to convince me to hate a fictional character. I actually like them more because they killed people. In fact, its the main thing I like about them. I would cheer with pom-poms at the mere implication of them killing again.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

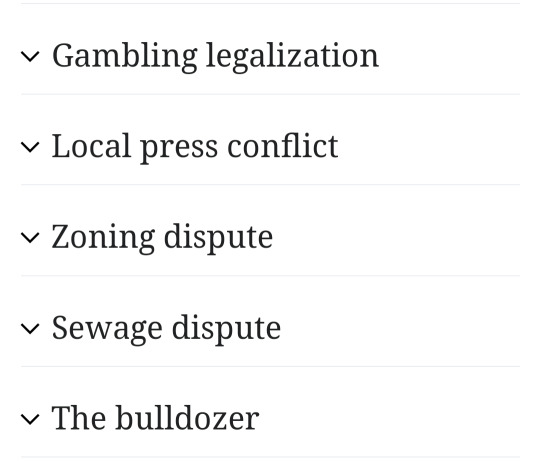

I love Wikipedia subsections that are just absolutely unhinged out of context

Peak comedy right here

50K notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been playing so much sudoku. You have no idea how much sudoku I’m playing. Every time I close my eyes I see the grid. I’m making moves in my sleep. 179432568. 653897124. 824516937. 915683742. 246175893. 387249615. 561724389. 498351276. 732968451. This morning before I was fully awake I was playing sudoku in my head. I rise with the dawn. I’m a warrior of numbers. You’re nothing to me.

43K notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s him. jimmy tomight dough

The celebrity Ben & Jerry's ice cream flavors being some of the best ones is like the retail equivalent of having to go to a restaurant and order a rootin tootin yeehaw cowboy burger or something

92K notes

·

View notes

Text

love when theres a character whose entire existence is spoiler tagged by default. go behind the curtain boy

29K notes

·

View notes