Photo

Hogsback, South Africa/ Brixton, London

1 note

·

View note

Link

A fantastic campaign that the BBC are currently running to encourage everyone to do something creative. Whether it's dance, art, drama, writing, singing, crafts, creativity brings out something in all of us that expresses our individuality and relaxes the mind. We are totally behind it!

0 notes

Link

An interesting view on being described as a 'maker', a maker of things

0 notes

Quote

Exploration is the engine that drives innovation, innovation drives economic growth.

Edith Widder

0 notes

Link

When I was at school 'resistant materials' as it was known was my favourite subject and my favourite place to be was the wood workshop. I used to stay after school to tinker about and fine tune a piece of work. Ok not everything I did was perfect but I was ambitious and that was down to great teaching, in particular the fantastic technician called Mr Howard who was so passionate about helping you create things, try things out, experiment. It's sad to read this article and hear how it seems that design education is changing. How can you design something if you don't know how it's made? How does this not remain the most important part of the design process? Computers are all very good but there is nothing like hand knowledge for understanding how things work.

0 notes

Link

An article to infuriate you! If this is what the education secretary is saying is there any hope?

0 notes

Text

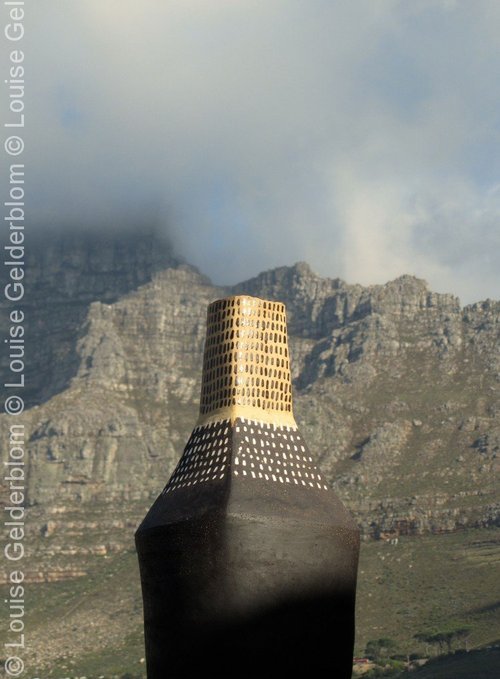

Louise Gelderblom: Part 2

While we were there, Louise took us down to meet her assistant Paul who was working out in the garage because her latest commission is so big! Paul works for Louise part time and is involved with the construction of Louise’s pieces. These are all hand built, coiled structures, which Louise then tweaks, and works onto the surface with texture and colour. In an average year she will produce 150 pieces, working on various objects at the same time. The duo has worked together for 12 years and Louise has much praise for Paul’s skills, describing that ‘he’s a superb, superb technician’. Their relationship is well balanced with their roles of artist and technician defined in how they work. Louise says, ‘we understand one another really well. I can make him drawings with measurements and he can execute them 95% of the time exactly how I want it.’

Their roles are so well defined however that Louise tells a story of how once she hadn’t had time to do a drawing. She described the piece Paul needed to make, but found it to be completely different from what Louise had had in mind. Despite making many pieces for her, it wasn’t her language: ‘I think that his value is truly in his practical skill where my value probably is more in my design skill.’

Much of our interviews so far have led us around these themes of artist, crafter, technician and maker. Louise and Paul’s working relationship of artist and technician beautifully depicts a process that we feel is often under valued. The praises sung to artists are usually placed in opposition of the role of a technician rather than beside them. Perhaps it is not solely about creating artists, with roles such as technicians seen as a step along the way; but rather to value the role and the working relationships of technicians in their own right. This does not conflict with notions of ‘idea ownership’ or ‘creative blurring’ instead it falls under the view that all creativity is to be shared, we are constantly playing some part within one another’s work.

Louise debates this question of roles; that there should be both separation and unity within the making process. Every skill and person should be valued, which is what makes a successful outcome but as the skills differ so should they be distinguished individually. She says ‘I’m always by the ceramic communities termed a ‘master potter’… what is that? And when are you a master potter? And who decides if you’re a master potter? Because in a way, Paul is a master of what he does…’

Within her studio she is the sole artist, so has refrained from employing more assistants, as it is her work and her involvement with each piece that creates her signature style. There is indeed the question of ownership and taking on more help would mean that: ‘that person who’s making that thing, it’s not their thing, they’re not caring about it that much.’ This is Louise’s view and in her studio environment one can value both roles whilst clearly viewing each piece as a part of Louise’s collection.

As the conversation continues, this topic of categorization comes up again as we refer to the many terms associated with making – artist/designer/craftsman/technician. Louise makes an interesting comment:

‘Say I was known as an artist and I had an assistant in my studio… I don’t think anyone would ever question, you know the division of roles. But as soon as you are a craftsperson or a designer maker… I don’t know, it’s a very strange thing…’

This statement highlights the misunderstood expectations of craftspeople and designer makers. Is it the change in working environment from a studio to a workshop, which changes ones expectations of makers toward both a high level of skills and an innovative approach to design? There is no less value in an idea should it be made by someone else, just as there should be no less value for the making process itself. Out of this one can see the importance in promoting an understanding and value for both within commercial industries and arts, crafts and design tuition; to challenge all to become “masters” of their field. Louise goes on to highlight this when explaining: ‘I think what’s sad in South Africa - I can only speak about South Africa, is a lot of people who train and get those technical skills immediately assume that they are now artists… there’s a huge need for product development of that sector of the craft population.’ As we discuss the craft sector in South Africa and the embedded skills within it’s many cultures, Louise lists the CCDI as a great attribution to the growth of the Western Cape Crafts Sector. But she explains once again how categorisation and varying levels of skill are a challenge particularly as craft often takes on many definitions. ‘They’ve (The CCDI) got a very hard mandate because they promote craft basically in the Western Cape but they have to not make a distinction between the guy at the traffic lights selling their handicrafts and the guy you know doing whatever else’

The discussion surrounding the distinction of craft and South Africa’s many skills allows Louise to introduce us to the term ‘fusion culture’ as she explains how ‘it’s a strange thing when you start intervening in a traditional craft process - that would also be like anthropology you know, how can we make this traditional clay vessel so that someone can put their flowers in it?’ She highlights the question as to whether a craft is still technically that specific craft, as its function has now been changed… As we all sit and consider this, it is concluded that:

‘You have to decide within a culture what are the traditional handwork and craft that you want to preserve and how would you preserve it? And it would be probably by nurturing those skills but also educating the public to make that a covetable thing.’ It is about swaying the development of a craft culture, changing the ‘wants’ toward that traditional craft, without losing sight of its true heritage?

As we spend more time in Louise’s world we realise that this is true not just for traditional crafts, but also for all makers and artists. It is a balance between your personal development and the market development.

How you want your work to go and how the market wants you to go?

0 notes

Link

Courtesy of the Southbank Centre website:

Work by new and established designers from Africa and the diaspora.

Africa Calling is curated by Kathy Shenoy (Shake the Dust) and Liezel Strauss (Subject Matter Art). This showcase highlights the work of new and established designers from Africa and the diaspora who are challenging 'African aesthetics' and exploring new collaborations and cross-cultural connections.

Focussing on designers, artists and collaborations from Africa's southern tip and the UK, this showcase includes a specially commissioned collaboration between upcycled furniture designer Yinka Ilori (UK/Nigeria) and knitwear designer Laduma Ngxokolo (South Africa).

Other exhibits include work by graphic artist Lakwena Maciver (UK/Uganda), the woven vessels of fair trade, artisan design cooperative Gone Rural (Swaziland), recycled plastic lights by Heath Nash (South Africa) and nature-inspired wallpaper by Clinton Friedman (South Africa).

From Friday 12 to Sunday 14 September.

Level 2 Foyers at Royal Festival Hall

0 notes

Link

We saw the divine knitwear of Laduma Ngxokolo at Design Indaba back in March and loved his designs for their fusion of the traditional and contemporary. It’s nice to see his work gaining recognition on a wider scale, a brand which gives value to its heritage and culture.

Laduma will be showcasing new collaborative work at AFRICA CALLING, a showcase of contemporary African design opening at the end of this week at the Southbank Centre's Africa Utopia Festival. Looking forward to seeing what other designers and artists will be on show

http://www.maxhosa.co.za/

http://africacalling.co.uk/

0 notes

Quote

The globalisation of artisanal crafts has led to the separation of the craft from the actual artisan. For example, various factories in China now mass produce and market ‘sari’ cloth, based on Indian designs, which finds it way into Western supermarkets and discount fabric stores, as tablecloths, placemats and bed linen. Thus it may be now possible to speak of the ‘virtual artisan’, meaning that the craft itself survives in a hybrid form that may or may not be produced by the original workers.

T.J. Scrase - Precarious production: Globalisation and artisan labour in the Third World

0 notes

Link

In the midst of all our interviews we came across this brilliant platform, show casing a variety of crafts from across South Africa.

'Love the Craft exists in recognition of the artisans, their skills, heritage, collaboration, traditions and every individual step involved in creating things of distinction.'

We love their promotion of both the traditional and modern forms of craft, once again exploring the different spheres into which crafts have filtered into...

1 note

·

View note

Text

Louise Gelderblom

In her recently converted Victorian house in Cape Town we enter the world of ceramicist Louise Gelderblom and her striking statement pieces that stand tall and proud in her studio space.

Originally trained as a graphic designer Louise started taking pottery classes with a friend in the 90’s as a hobby. She found that with graphic design becoming ever more digitally based and having no desire to sit in front of a computer all day, her love of ceramics began to take over. Louise describes what drew her to ceramics, explaining: ‘What I really like is that you are the master of the clay, that you can do anything, there’s no limit… so I find that very empowering.’

This sense of control over the clay is perhaps why Louise’s sculptures reach such a grand scale and together with her bold surface decorations they radiate confidence. But there is also such elegance to the forms and the hand detail work that exposes and connects you to the process.

It is also nice to see the sculptures clustered together around the room instead of on a white plinth in a gallery, removed from its context. Here in her tall ceiling studio they look at home in the space. This natural and unpretentious presentation of her work reflects the meticulous yet liberating practice each piece embodies.

Louise feels her informal introduction into the world of ceramics has in many ways shaped her approach to making. ‘I went into it and I was quite fearless, I was completely uncautious and unscientific… sometimes it’s better not to know too much’. As we ourselves have entered into the world of ceramics along a very structured academic path, we found Louise’s freedom in both her practice and perception of ceramics inspiring. Her work is mostly coiled and in her “unscientific” manner she does not mix glazes but rather uses combinations of readymade glazes and slips. For Louise, it is about how she applies them, in what combination, and on what textured surface, these are the subtleties that provide each piece with its signature aesthetic.

However Louise does say that when teaching from her studio she does stress to beginners the importance of test tiles, ‘at least at the beginning - it’s not a spontaneous thing that you slap on the glazes and it will be amazing’. Her use of glaze is often quite expressive and ‘painterly’ although with an element of order – she gives us a ‘trick of the trade’: to ensure even coats of colour, if you want to stop to make a cup of tea, make sure you draw a line where you finished, ‘because there’s nothing more frustrating than having a blurry patch!’

Louise makes no qualms about her feelings towards the market and exhibiting nowadays. She hasn’t shown at the Design Indaba for a few years now and her work is stocked in only a few galleries. She’s become quite disillusioned by the effect the market and consumers can have on your work. She takes everything with ‘a huge pinch of salt’.

And it is true, the market these days dictates consumer buying - magazines only have to express their love for a certain colour, pattern or material to determine the next ‘trend’. This is out of sync with a maker’s creative development and loses touch with the beauty of a handmade object, turning buying the handmade into a fashionable ideal. We believe that this devalues craft, attributing to societies ‘throw-away’ culture and ultimately narrowing the market of true crafts. It is the demand for ‘objects’ on trend that blurs the boundaries between the handmade and the mass produced. The lack of understanding behind how and why objects are made have resulted in objects being compared rather than distinguishing the value between something that’s been crafted and something that’s been cheaply manufactured. Louise highlights this point of view, explaining: ‘I think that a lot of craft industry is being killed off by… Mr Price, Ikea…’

Louise stands firm in her belief that you should be true only to yourself as a maker. She learnt early on that ‘I must make absolutely only ever what I want to make. I must never think the market must like it’. So as a result she is her own boss; she dictates her working rhythm, her style and knows if people want her work they’ll ‘do their homework’. Half of her sales come through her website, a lot being international customers.

Her work reflects this confidence and assurance in its scale and solidity and definite style. She says that sometimes people are slow to buy ‘new’ as she develops her work but there is a clear pattern and process, her objects are a family of monotones and graphic pattern. ‘I do feel strongly that work that I do now can sit comfortably next to work that I did 10 years ago because it’s my thought, you know, it’s not a product.’ This was very much obvious as we spoke, surrounded by her body of work.

Louise’s pieces very much fall between that of craft and arts. The term craft has become synonymous with do-it-yourself, novelty objects and has lost all integrity. But in recent years it is being reclaimed, Louise herself is an example of the successful bridging of artistic exploration and expression, and technical ability within a traditional material. This, for us, is a depiction of true craft. Louise’s stance on being true to ones work, has led to her success in both the art and craft worlds. ‘I think that’s very important, I think that a lot of work loses its integrity because the maker is trying to answer market needs.’ Louise elaborates on how a lack of trust within ones own work affects the long term outcome of their work: ‘for me it is interesting because, that for me is a hobbyist approach to ceramics (conforming to the market) as opposed to somebody who does it as a living.’

We discuss the status of ceramics. Louise comments that: ‘I don’t know how you experience ceramics but it’s always the sad little relative of everyone else!’ Perhaps this is why she chooses to stay away from becoming so commercial. Instead her work is unique, each piece offering a subtle nuance of her ceramic language. She says ‘I suppose I’m an artist designer maker…I think that the work probably is more in the realm of sculpture than functional ware’

We paused for refreshment – and wow was it refreshing - the best ginger and lemon grass cordial we have ever tasted!

Have you got the thirst for more from our interview so far? Well more to come in Part 2 very soon…

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lovely find

Since 2011 Shake the Dust, founded by Kathy Shenoy has been building an exciting platform for ethically designed and produced products. Through its collaborations between British designers and producers in developing countries, the brand truly epitomises the idea of Here and There; from the process to the market place their beautiful handmade homeware and accessories connect cultures and exposes ethical design to a global market.

Fluoro Vases by Gone Rural, Swaziland

As part of the Alchemy festival at the Southbank Centre in London, Shake the Dust will be curating Design Wallah, a showcase of South Asian Design. From interiors to jewellery and gifts the pop-up shop looks set to offer a fresh contemporary selection of diverse design including the work of Safomasi who create colourful, boldy printed products that reflect the couples mix of cultures and influences from their travels.

See them and more at the Southbank Centre from 15-26 May.

0 notes

Text

Binky Newman and Design Afrika

The Design Afrika showroom in Woodstock is an Aladdin’s cave of baskets. Floor to ceiling and every shelf in between there are baskets galore, it in itself a study of Africa viewed through the array of woven wares.

Binky Newman, founder of the company welcomed us in and amongst the baskets we began our interview. As the alluring smells of typha and imizi plants drifted in the air, she began telling us of how she has lived and travelled all over Southern Africa beginning in her birthplace, Namibia. She clearly has an inherent love for baskets and ‘all things woven’. Recalling the time spent in the Okavango in Botswana, she would watch how ‘the (Hambukushu) women would be walking down the runway near where my camp was and they would have these big baskets on their heads and I would just melt… they are among the most interesting and finely made’.

This passion for the intricacy and beauty of these baskets is what carried Binky’s collection Design Afrika forward and has now been running for 20 years. She currently promotes 19 groups of weavers from all over Africa. Some types of baskets were on the verge of extinction prior to their incorporation into the collection, having only survived in communities that made the baskets ‘for themselves and their own use or for bartering’.

This idea of ‘everyday craft’ reminded us of the craft villages we visited in Bangalore, India. Binky has had similar experiences during her travels to India; she started an NGO in the 90’s called The New Basket Workshop, based in Johannesburg that involved collaborative projects between India and Africa. She explained how crafts still remains so embedded in everyday Indian life; most items are produced for immediate use in the community, as a result crafts will ‘hopefully never die out as there will always be a need for these products.'

To us South African crafts seem at a transitional stage between this idea of everyday craft and their contemporary development, which has opened them up to new markets. The industry has a raw, uninhibited quality to it, not just through the ingenious uses of local or waste materials or its connection to tradition and culture but the energy within the work, the spirit of new and exciting things. Binky agreed: ‘Craft in South Africa is taking a while… it’s still relatively young. During the bad years we were very isolated so we didn’t have much tourism for a start and certainly not many exports so that’s all happened latterly and in terms of various government programs, craft was at the bottom of their list, they really weren’t interested.’

The instigation of craft as a tool within government initiatives is indeed fairly new, running hand in hand with the governmental push toward co-operatives. However these programs often divide between those that are designer led and those that teach skills with a participant-led focus, both methods having their pros and cons. A great drawback is a lack of understanding of both the market and the work involved in making a success of the ‘craft’ tool.

Binky herself has a background in marketing, having first set up concept stores that sold various hand crafted items, at first English crafts and then as her interests changed and her eye for African craft developed so did the objects she wanted to sell. She started working more in rural communities seeking out the woven treasures and building a collection to promote which embodied ancient traditions.

She now has two ranges of baskets, some functional and others purely sculptural, developing new shapes with the groups of weavers she works with. She describes a Xhosa basket, Ingobozi, which women use to go to the fields. It has a little indentation on the bottom to sit comfortably on the head. Working with the women of the Masizame Women’s Project in Coffee Bay she developed a new range of gourd like shapes, which now continue to be developed by the women under the guidance of Nomonde Madlalisa. Binky explained her progression from marketer and seller toward designer, explaining ‘The designing came later once I saw the need for a bit of change. Then I started designing and redesigning and adapting. Once I saw how a small change could make a big difference to a product and make it more contemporary then that’s when I started tweaking.’

In her latest project, Binky is working with women from the Du Noon Informal Settlement just outside of Cape Town. Many of the women have never woven before so a local weaver from the Eastern Cape was brought in to teach the women the basics of traditional weaving. After which Binky and product developer Mara Fleischer have been working with the group to develop new shapes and products. They are also developing a range incorporating everyday existing materials such as enamel bowls, plastic bags and cable ties. This merging of everyday modern, culturally specific materials and traditional materials reflect previous ideas we have discussed regarding the growth of fusion-cultures and the adaptation of craft to stay alive and relevant. It is also a beautiful representation of South Africa, its amalgamation of culture, people and materials in beautiful objects.

We were also inspired by the open approach both Binky and Mara have toward the market, explaining how ‘some of them (the weavers work) are just really rough and so we’ve celebrated the roughness. This (pointing at a basket) for instance, it’s not tightly woven and the material is very coarse but it’s a different look, a different style and it will appeal to somebody’. This open-mindedness and positive approach shows that though some markets may be fussy to embrace new products, it is broad; the strength of the business has been their understanding of offering diversity to a large customer base and maintaining that richness of culture in the newly developed products.

As we continued to discuss the Du Noon project, Mara arrived with fresh experimental pieces from Du Noon. We were amazed by a new piece they’ve been collaborating on with Clementina van der Walt. It’s mix of both ceramic and weaving bore a resemblance to Emily’s work, once again reminding us of the Here and There Project; how aesthetic themes and ideas are not owned but rather explored within many contexts and cultures.

Binky has managed to create a system where the boundaries of design and craftsmanship are blurred and there is a mutual respect for wanting to preserve and promote the beauty of these baskets and their continued use in contemporary society.

________________

We thoroughly enjoyed our visit to Design Afrika and were also so pleased to visit the Du Noon Urban Weavers and see the product development in action. See our post about the time we spent with them here. We’d love to do a whole tour around Africa now to see all the other weavers at work!

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

What an interesting talk by Gever Tulley, founder of the 'Tinkering School', a summer camp in California where kids can go to explore their imaginations. They are given real tools and real projects to creatively problems-solve... we want to go!!

www.tinkeringschool.com

0 notes

Text

Chris Silverston and The Potter's Workshop

The Potter’s Workshop runs from within the relatively new Capricorn Business and Industrial Park in Muizenberg. In this modern and peaceful setting we made our way to our next interview. Established by Chris Silverston The Potter’s Workshop produces decorative functional ware in their unique African aesthetic. It is brightly coloured and incredibly intricate, with a strong visual connection to the detailed beadwork associated with African craftwork.

As we pulled up outside of the workshop there was a quiet buzz of productivity. The windows and shutters were open showing off the team of 27 hard at work over the two floors of the studio. We found the clean and tranquil studio runs rather unconventionally – the ground floor houses mainly women who slipcast and prepare the clay forms which are then taken to the second floor, where there is a team of male artists who adorn the pieces with their beautiful patterns. The workshop also has an area for stock and orders for delivery. Every stage in the production process has its place. We couldn’t help but note that the space was incredibly clean for a studio allowing the vibrant colours to burst out at you from the finished works. But the neat and orderly space only goes to reflect the precise pattern work of what is created here, each section reflecting the care and consideration taken into the production of each piece. Like the stock room, the administrative office is also sectioned off from the remainder of the studio. This is where we met Chris, along with her assistants Narieman and Lorraine. The full studio depicts Chris’s work ethic, which she has fostered within her business; it is one of professionalism and organization. ‘I run an incredibly tight ship’, yet there is still a family feel to it as many of the staff members have been working alongside Chris for many years.

Though the word business is synonymous with the formalities of trade and commerce at the heart of ‘The Potter’s Workshop’ one can clearly see Chris’ creativity and passion for ceramics, which she has turned into an entrepreneurial enterprise. As we sat down to a cozy cup of tea, served in their beautiful cups and saucers, Chris began to tell us of her pioneering journey into ceramics. ‘I’ve never fallen in love with anything like I did with pottery, it was, for me…it was music… and I remember the feeling of learning to throw…the sensitivity in my fingertips. I worked at it every day and then apprenticed myself as a potter and never looked back’.

With family in the UK, Chris had the opportunity to study art over there. After completing a year of graphic design at Coventry Art College she was told she’d be better suited to another art college as her work was too decorative for them. And how right they were! But it doesn’t seem to have done her any harm. She talks about how the course was ‘so unstructured… when you’re so young, you need to be shown how to do things, told what to do, it was terribly daunting…’. We couldn’t agree more having had similar experiences in our own skills development. The conversation soon lead to the topic of teaching methods. We discussed the importance of having a foundation of skills knowledge from which to draw upon before actualizing and developing ideas. Chris herself is a champion of apprenticing, explaining that ‘one of the best methods of teaching is apprenticeship, it’s what you need and in a way, it’s what’s happened here…’ She has nurtured her staff, allowing them to establish skills not only in ceramics but within the design development as well. A couple of her success stories are Andile Dyalvane and Madoda Fani. Andile now runs his own studio Imiso Ceramics from the Biscuit Mill in Woodstock. Throughout Andile’s apprenticeship and in the continuation of his studies, Chris has always been a supporter of his rise in the South African arts world. This positive environment has allowed the artists at The Potter’s Workshop to be expressive through their pattern work, and in developing their own working styles. The development of their products is a joint venture, with the concept often established by Chris and an artist. Though the artists may develop a signature pattern or look to their work, Chris is always there to critique and help refine; always showing a very keen eye, she has a great understanding of the market and follows her gut when viewing possible new work… if ‘she hates it, she hates it’! A friend once said to her ‘Chris, you shoot from the lip’!!

When asked about the driving force behind the work, she professed that this business may involve a craft but the main objective is about ‘putting money on the table… people are supporting at least 3 to 5 people’ – 50% of their turnover is spent on wages. So it is imperative to keep a tight hold on finances and maintain a strict quality control. This balance between creative output and managing a business is a skill many struggle with, yet throughout the market challenges of the past two years they’ve remained a thriving business. This is due to Chris’ knowledge of the market and its need for expansion, as a result they have begun selling within international trade fairs such as Birmingham’s Spring Fair and the New York Gift Fair.

Whilst the motivation may be to give people a job there is still the importance of the skill behind the work. Chris has created an environment where everyone supports each other. She noted that ‘there’s a lot of, I can use the word cross-pollination of designs between them (the artists), they pick it up from each other. Now what happens is they train one another, but it takes a good two years…’.

We got a chance to wander around the studio and meet some of the artists and workers. Everyone seemed relaxed yet focused with each workspace shared and open. Chris believes that this process of sharing work is inherently African and describes ‘the thing about South Africa is we’re very primitive; we pick up on ideas. You see things and you think wow that’s good, let’s try it!’. This fusion of culture and ideas has resulted in the South African crafts evolution into a true representation of its multicultural history and future progression. And it’s an observation she further realised after her time in the UK:

‘My feeling about British craft was that is was so refined, so developed – like taking a pencil and sharpening it, they sharpened and sharpened and sharpened, there was no room for innovation. I think this country is extremely raw, exciting and unafraid, we’re not hemmed or bound by all those kinds of constraints.’

And perhaps the vibrancy of Potter's Workshops products and ethos equally represents this fusion; that to maintain a successful craft company there must be a balance of business acumen and creativity, between the reality of providing employment and the beauty of creating.

‘Craft has got to be functional and it’s got to be aesthetically pleasing and I mean we live with our craft.’

Creating a closer connection to the handmade object is imperative to crafts survival, through market appreciation and through the individual desire to seek beauty in the everyday objects we use. The Potter’s Workshop in their working practice and beautifully made pieces embodies this concept. It is through companies like these that craft will not only survive but thrive.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploration Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time.

T.S. Elliot, Four Quartets

0 notes