Text

VideoDrone Rebirth: Calendula

(Hi everyone! A longer note on this will be up on my patreon free to all, but Videodrone is now weekly again with the new year! It seemed long overdue to me and I deeply miss talking and writing with you all. As always, the relevant links are still relevant – www.patreon.com/hegelbon for the patreon and www.twitch.tv/hegelbon for my twitch streams – and now I have a paypal also if you’d like to do a one-time jawn – www.paypal.me/hegelbon . Thank you again for all of your support and here’s to a content-rich 2017.

Also, uh, probably here’s to a name change so people can find us on Google in 2017 too. So any suggestions, shoot.)

Experimental games are always a bit of a crapshoot, particularly when they’re coded using the Unity engine. There are enough “find the pages” Slenderman clones to drown in, and even when games attempt a bit more ambition (see our previous review of Kholat), the constraints of the genre recur – find pages, reveal a story bit by bit, and escape a monster. Even worse, experimental indie games often are rife with malfunctions and game breaking bugs. Unfinished, unpolished, and unplayable, many an ambitious game has ended up wearing the unenviable “ambitious, but” tag.

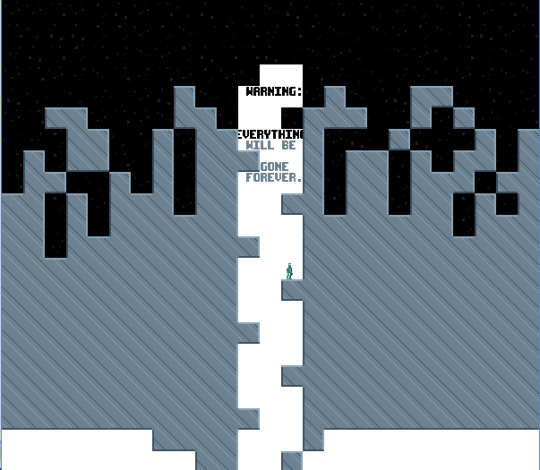

And so, when you introduce your experimental horror game made with Unity, most people are going to think “Ah, a spooky mystery game revealed bit-by-bit that I probably can’t even play all the way through.” What’s interesting about Calendula, an ambitious and experimental horror game coded using the Unity engine, is that it responds to these critiques in the affirmative, loudly proclaiming that, yeah, it’s broken and unplayable and mysterious, and that that is the point of the whole experience. Calendula, in short, is framed as an explicit self-critique from its first moment as a game: the title screen.

Keep reading

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Videodrone: Overwatch

((Hey all, as always please consider donating to the patreon at www.patreon.com/hegelbon. Also keep an eye out for video versions of Videodrone coming soon to my youtube channel, which you can find here. This post will be up in A/V form by tomorrow if all goes well. Thanks!))

So, in full disclosure I should admit that I used the Overwatch free weekend to get into probably the most popular current game of the past five years or so. I did this in large part because I’m very cheap, but also because I finally have a computer that I thought could credibly play the game. So I thought, why not right? Even if I only get a couple of hours in, it’s a good time for free and maybe I can write about it at Videodrone. Well, uh, yes and yes: beyond my expectations.

The thing I didn’t realize about Overwatch was that it was not just a cultural phenomenon surrounding a relatively decent shooter. It was a really top-top tier shooter that produced a cultural phenomenon. This might seem like a pretty fine distinction, but Blizzard has really produced something special in the game itself and, not so incidentally, has produced a series of culturally resonant characters to go along with their brilliant design. The two go hand in hand, as any brief search of Overwatch fan fiction, fan art, or pornography will reveal, and a large portion of Overwatch’s massively positive reception seems to have to do with the fact that it is openly representative of people who generally are not represented in videogames. It’s just that that’s not all it’s up to either

But let’s talk about the characters first, anyway. The general caveat against seeing representation as an end of politics of course applies here – listen, Blizzard didn’t include a diverse and differently shaped cast because they wanted to be nice or advance the cause of more just politics around race, gender, and sexuality, it was for profit. But with that said, I think there’s a very formally interesting quality to the diversity of Overwatch’s heroes. The game takes the Mortal Kombat route of keeping much of the story hidden in the background, so each character becomes a sort of legend upon which you can project yourself, and there are a lot of options. Different races, species, ages, even body types populate Overwatch. And in a shocking move for a high profile videogame, they almost nail gender parity – 10 of the 23 playable heroes are women. And not just waifish white women either: women in Overwatch are just as likely to be offense heavy as they are to be support.

What this means for players is that they can gravitate to the characters they feel an affinity to without having to suffer poor play as a consequence. For instance, I’m old and out of shape, so I usually went with the over-the-hill hero Soldier 76 and the massive biker tank Roadhog. This gave me a ton of flexibility, depending on the rest of my team, and the game totally doesn’t penalize you for experimenting with different roles, as you can swap out heroes every time you die in game if you choose. So, while you never feel married or trapped to a particular hero, Overwatch allows you to feel at home in your avatar’s skin, a gesture that allows both self-actualizing play (”Hell yeah, I’d be so good at fighting in an arena”) and, more importantly, fan investment in otherwise Orphic but opaque character types. Beautifully designed and without a clear set of origins in-game, the Overwatch heroes are totally open to community investment – a sort of Benedict Andersonian imagined community of gamers if you’re feeling optimistic, and a heck of a guerrilla marketing campaign if you’re feeling grouchy. Either way, it’s fairly remarkable.

Beyond the characters, as I said before, the game itself is designed in a really unique and effective way. I’ve had a number of discussions with my friends about what exactly Overwatch is as a game. Obviously, it’s a first person shooter, and we can’t really get past that. But on one hand, it’s also a bit like a fighting game, as each character has a set of specific moves that they can use to specific effect, as well as a series of very particular weaknesses, as well as an ultimate attack. On the other hand, the game is a lot like capture-the-flag games like Team Fortress 2, based around quick but mercurial team cohesion and rapid-fire win-loss scenarios and repeated tactical plans. And on a third hand, snaking its way out of your abdomen, it’s a MOBA, marked with the same tell tale signatures of Dawn of the Ancients 2 or League of Legends, just with a lot less complexity: tanks, supports, offense, and defense; deeply specialized movesets that require very specific timing; and a team mentality that is literally required for any modicum of success. Somehow, Overwatch manages to be each and every one of these pvp genres and manages to be it at an incredibly high level. Which of course makes for addictive, non-stale gameplay.

I think in the end, I lean toward the game being a bit like a MOBA for a more casual class of gamer, eg me. I like DOTA2 a lot, but make no mistake, I’m terrible at it and I’m not going to be any better any time soon. With Overwatch, it took two or three hours before I could actually say that I was pretty comfortable in deathmatches, which is a remarkably light learning curve. The game, in many ways, works the way for the shooter that Super Smash Bros did for fighting games: it makes the genre lighter, faster, and more easily accessible to new players without ratcheting down the game quality. As such, it opens up the form to non-insiders, in much the same way genre fiction or popular cinema might in other media. It’s an entry point.

But what’s so fascinating about Overwatch is that it’s not just an entry point, but an end point also. You could literally begin and end your videogame career in Overwatch and not bat an eye. In that way, again, it’s like Smash Bros, which thousands of college kids became experts at while never giving a damn about any other videogame of the moment. And what this does for the form is it allows access to a class of spectator who isn’t particularly concerned with the history and future of videogames, who isn’t at core a gamer. This is important for profit, of course, also, and I’m sure Blizzard is thrilled about that. But beyond that, Overwatch offers a new audience a way into a form that is all-too-often completely unwieldy to newcomers.

So while the cartoon violence, easily identified-with characters, and sense of simple rules that are impossible to master inform the way in which Overwatch is played and received, the important part of the game has more to do with its underlying philosophy. Don’t, it seems to suggest, turn anyone who wants to play away, and you’ll get a better game for it. The videogame community is usually set hard against this philosophy (see my posts on Dark Souls), but quality counts, and Overwatch is doing enough to avoid immanent critique from its base. As a result, we get the videogame version of the novel of manners or sentimental fiction: an entryway into the form that will allow access to its next generation of creators. If Overwatch has a lasting legacy – and it almost certainly will given its standing and popularity – this might be it: that it allowed the people who further defined the form in to sit at the table in the first place.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Videodrone: Elections

((Hey! So sorry for the layoff, but we’re back. And accompanying this Videodrone will (hopefully) be a video package with audio as well. As this is still new to me, it might take a little time to get my legs, but I’m excited about expanding the project out! As always, if you feel like you’d like to support me further, please visit www.patreon.com/hegelbon, and thanks so much for reading.))

On the off-chance you are some sort of cautionary New Yorker style cartoon or literally the biggest contrarian on the planet, you might know there’s an election tomorrow (or today if you’re reading it later; the election is/was on Tuesday the 8th). The stakes of the election are fairly high in a national sense, given that it’ll determine a new president as well as the makeup of congress generally; I, thankfully, am not here to talk about that election. If you’re anything like me, you’ve had quite enough election chat and debate, and frankly my additions (I’m disappointed! I don’t feel like anyone’s radical enough in the way I want them to be!) are as predictable as they are useless. So let’s talk videogames instead.

Keep reading

1 note

·

View note

Text

Analyzing Sports and You

Okay, I’m limiting this to a half hour because no one is going to pay for or read this, but I feel I need to concretize some ideas that I’ve had about advanced football analysis. Off the bat: advanced football analysis, the type for which we’ve seen Football Outsiders and Pro Football Focus become famous, is a noble enough endeavor. It is important that we stop seeing the games we love through the standard box score lenses we’re used to. Maybe it’s important because we want to be scouts or GMs someday; maybe it’s important just because we want to be better fans, knowing who deserves the credit and blame outside of normative stereotypes. Regardless of motive, it’s totally fine and in fact progressive and good to want better stats. It’s what baseball has been up to since Bill James decided to mimeograph a bunch of pamphlets in the garage, and it’s good and timely that football is catching up.

That said, I am not particularly impressed with the current iteration of advanced football analysis. I’d mince words, but after a war of words on twitter today, I doubt I’m anyone’s fav over at Football Outsiders, and generally my inability to market myself as a football fan makes me invisible on the gridiron freelance beat. So whatever, let’s just say what we mean: these sites do interesting work, but it’s interesting work that is outdated and flawed. I’d like to explain why I think this.

The outdated bit is arguably the less hot of these hot takes: I think advanced football analysis is slowly and unnecessarily working through the missteps and growing pains that sabermetric analysis did from, say, 1990 to now. Call it post-Moneyball the book and pre-Moneyball the movie. In that period, it was common to fetishize the three true outcomes above everything else, get furious at the valorization of any other skill attribute than patience, power, and pitch speed, and basically get real rebellious at the old Dad Figure of Joe Morgan.

In lots of ways, this period kicked ass, since it spawned Fire Joe Morgan and The Dugout, so I have almost no complaints. But a lot of the analysis, looked at now, is a bit dubious. We all have our columns where we champion Brandon Allen or Wily Mo Pena, arguing that they’re blocked by reductive/racist/boneheaded/traditionalist/etc managers and GMs who don’t know how to use them. We all had our GM heroes who could do no wrong, and the ideology of Billy Beane was – despite our clear expression that it was not – as close to a religion as the discourse had. Basically, sabermetrics hadn’t killed its heroes.

And then, as the 2010s began, something strange happened – we started questioning stuff fairly aggressively. Baseball Prospectus’ Ben Lindbergh and Sam Miller (now both sadly no longer with BPro, but happily onto bigger things) and Fangraphs’ Eno Sarris and, heaven help me, Carson Cistulli were some of the most thoughtful pioneers here. They began to question whether our biases have helped us ignore players that were actually good; whether power and patience were actually the only skills that mattered or whether they were simply scarcities during a period where we cared about scarcity; and whether we really did have a good model of “player value” in Wins Above Replacement (or Wins Above Replacement Player, or Value Over Replacement Player, or rWins Above Replacement…you get the point). The step the baseball analytical community took, in other words, was to look at all the truths it had set up as sacred and question every single one.

It seems to me that the football analytics community ought to preemptively do the same thing. The specter of having an outdated draft claim akin to “Brandon Allen is better than Paul Goldschmidt” is scary enough to my mind that any analyst worth their salt would immediately doubt any sort of received thought they considered true. And yet, critiques (valid ones!) of management, drafting strategy, and racist pigeonholing of players in particular skill positions have lead analytical football writers to fall into the trap of proving others wrong instead of looking at what’s in front of them. This is what leads to hot takes about “the kind” of quarterback that can succeed, or breathless mockery of teams at the top of the draft or thereabouts who “reach” for a bad player. There’s a player every year who is a special player – Myles Jack this year, and partly Jalen Ramsey – and players who are overrated. Yes, this is about Carson Wentz.

But while I will happily let it be known that I am an Eagles fan obsessed with and convinced by Wentz, I also want to insist that this article isn’t really about him. No, it’s more about what Wentz represents, which is these analysts’ stubborn inability to study what they got wrong. And some folks do, don’t get me wrong – Ben Natan, John Barchard, Derek Klassen have all turned around on Wentz and thought about what they could have missed. And while Ramsey has hit undeniably, I’m sure there are those souls in Jags twitter doing the opposite kind of analysis on Jack, and in Rams twitter doing that analysis on Goff, etc, etc. The problem is that there are still loud voices that remain egotistically bent on justifying their pre-draft grades on players.

In baseball, this problem resolves itself – you can believe in a prospect all you want, but if they can’t make it past AA, welp. But in football, the range of results on a player are much wider and much more subject to personal interpretation. This is all well and good for casual conversation, of course – you can talk about if Joe Flacco is elite with your uncle or whatever and really enjoy yourself, and I say go with god. But the problem is that if you’re planning on having a serious scientific analysis of players and their abilities, you need to be more exact than that. And DVOA, All 22, and casual non-trained scouting of film is not exact; or put more kindly, it’s along the spectrum of exactitude, but not nearly there enough to be confident in.

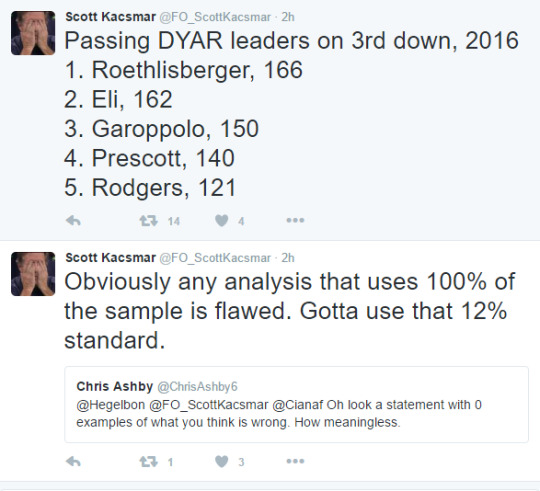

And yet, on twitter there is the pretension that the whole analytical community is the smartest person in the room, empirically considering 100 percent of the data while us proles nip at their heels. I’m blocked by this guy now because I disagreed with him, but if you’re not here are some examples:

Imagining that you look at 100 percent of a deeply complex and subjectively tinted game and come away with the only empirical analysis is not just flawed thinking, it’s egotism and it’s dangerous. Even worse, we get accounts defended by stats like DYAR that gets zero skepticism or self-critique. These are tautologies – the players are good because the metrics said they’re good. And the metrics are good because they show us the good players. It’s silly and juvenile, but mention that the process looks a lot like the failed attempts of a now more mature sabermetric enterprise, and you’re out of the magic circle.

In the end, football analytics has its own problems that aren’t encompassed by sabermetric analogues, and I can admit that too. I’m not as good at interpreting the NFL as I am MLB; I’m fine admitting that also. But even if I’m wrong on Wentz or Jack or Goff or whatever, it doesn’t excuse the lack of self-critical method and intellectual doubt that’s rampant in these circles. When this is your go to sense of self

it should come as no surprise that your work is attacked as a project of ego-proof than anything else. And when your thesis is “I was right, and let me prove why” then all the All 22 and gifs in the world won’t save you from bad thinking.

Football, like any sort of thing-in-the-world, is driven by subjective analysis. When you deny that you’re vulnerable to being a subject, and when you insist that you’re immune to any bias, then you’re just a god to yourself in your own thinking. There’s a lot to be said about advanced football analysis today; it’s just not being said by the people who are trying to prove a point instead of trying to learn something new.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Videodrone: Undertale

((Hi everyone! I’m excited to announce that the patreon made its first stretch goal! So we’re going to see reviews of every MGS game in the space soon! I’ll pace them, don’t worry. And if you’re interested in seeing more stretch goals or seeing the new perks subscribers can get, check out www.patreon.com/hegelbon. Thanks!))

It’s an intimidating thing to write about Undertale. That’s an opening line I feel like I’ve used before, and if I have, I regret using it for any game that isn’t Undertale. It isn’t as if Undertale is some sort of monumental masterwork that freezes any would-be critic in her tracks, but rather that the game has such a wide fanbase, that you can almost be sure you’re not really bringing anything new to the table. Think of it like trying to get a new angle on Shakespeare 400 or 500 years down the line, but also in this instance, Shakespeare has a bunch of people writing their own fanfictions and coding their own plays about relationships between, like, Laertes and Horatio. I uh may be getting a bit far afield.

Keep reading

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Videodrone: Anatomy

(Thanks to my friend, @jacquestristan for the suggestion of Anatomy and for the donation of the game itself. Truly an excellent suggestion.

And if you like the work here, please consider donating to my Patreon! It’s at www.patreon.com/hegelbon

Also if you want to buy Anatomy – and you should – it’s availble here –https://kittyhorrorshow.itch.io/anatomy ).

As I’ve written more and more of these, I’ve realized that there are a few things that I differ on with the rest of the gaming review community. For one, I think most people who write about games are less interested in the games as pieces of art and more as experiences: you can see my last post on hacking games for a worked out account of that difference through the lens of self care. I’m also pretty convinced that I’m less interested in justifying games as art than most critics, despite the near-constant claims that the debate over games’ status as art is over and done with or irrelevant from the get-go. And most of all, I think I’m on an island in thinking about games as extensions of literature.

This latter point will be important today, as the game I’m covering – Kitty Horrorshow’s tremendous Anatomy – has garnered quite a lot of critical acclaim, but all or most of that acclaim has worked to think about the game as indebted to filmic techniques and strategies. I’m going to talk about the game in a way that rejects film theory as a lens for two reasons: first, I think it limits what the game can actually say as a piece of art; and two, I think it makes it very difficult to take the game on its own terms. Far from being beholden to, say, German Expressionism, I think Anatomy produces a critical account of domesticity and the haunting quality of physical media that exceeds any of its anxious influences.

The game itself has a simple enough premise, and is truly a walking simulator – there is no way to die nor are there enemies or the jump scares you’d find in a typical survival horror game. I don’t mean to disparage the game by pointing this out, either. I think the walking simulator genre is a useful expression of the medium’s capabilities to represent spaces and places in a specific way: take out the difficulty and exigency of survival and you open up the player for more serious acts of perception and exploration. And Anatomy is deeply interested in exploration and perception.

The game begins with a clicking and whirring, and it’s unclear if that’s keys opening the house that you find yourself in or whether the sound is the particular clicking and whirring a VCR might produce. The ambiguity between experience and recorded experience is a central theme of the game, as it opens with a blue screen that recalls the blank parts of a tape from a camcorder (only 90’s kids, etc, etc), and the game rolls tracking lines and color degradations that you’d expect to find on an aging VHS cassette. Anatomy, despite its titular promise of body horror, presents a sort of data horror akin to films like Videodrome or even The Ring – the fear that the materiality of data on magnetic spools somehow exceeds its boundaries.

The other twist in Anatomy is that the game has multiple endings that are not determined by user choice. You have one path through the game, but the game restarts you on that path several times, and even ends the path “permanently” (though the readme gives you a trick to restart your game). Spoilers from here, I’m afraid.

…okay?

The game has four discreet playthroughs: one in which you explore the entire house while listening to fairly legible lectures on “The Anatomy of the Home” and which ends abruptly in the teeth of the bedroom; two, in which you are reborn in the entrance to the house, but the tapes are now noisier and staticky, and glitches are more common; three, when you wake up from being pushed down the basement stairs, and are faced with an almost unplayably (on purpose) home, falling apart at the conceptual seams; and four, after the house has “digested” you and you wake up in its stomach. The final screen is a tracking-laden shot of a tape recorder that tells you a story about what abandoned houses do while they wait for new owners, and after it switches off, the camera does not move and the game is no longer playable (unless, of course, you hit “delete” and start over).

The fascinating thing, technically, is that the game exits completely after every “death” and needs to be rebooted. And at each reboot, it starts again, though with consistently more glitches and mistakes and errors built in, even into the loading screen. By the end, the familiar blue VHS placeholder becomes a blood-red screen with barely readable courier text that says “You never came back.” Furthermore, the captions in the game, as well as the hints – “There is a tape in the downstairs bathroom” for instance – become jumbled and confused, degrading into things like “Hhhhhhhhhhhhurts” by the final playthrough. Anatomy effectively works the tutorial into the meat of the game itself, and the tutorial elements of “Well here’s how you play the game” don’t disappear but get as mangled as the rest. It truly is the total destruction of a form.

Thematically, the game hits on two topics: domesticity and videotape. Domesticity is the one that probably jumps to mind first, given Anatomy’s setting and content, and the game is certainly interested in working out issues of what the home means and entails, especially what the empty home means and entails. I think Kitty Horrorshow has worked out one of the hardest elements of horror quite well, in that she never quite reveals the monster or explains the horror behind the veil (which would, of course, make it no longer scary; cf: every horror writer ever). But at the same point, the literalization of the anatomy of the house – that it even eventually eats and digests the intruding body, that is you – is secondary I think to the parlor play horror happening behind it.

What Anatomy reveals by being totally resistant to jump scares and traditional horror, as well as being totally resistant to the collector mentality of a normal videogame, is that the horror of the house has nothing to do with the stories it holds or the objects it contains. Instead, the domesticity of the horror house in Anatomy is itself the scary part. The reason we’re scared in our houses at night is because we assume each creak or pop is actually something aberrant, something that isn’t part of the house’s normal function. In Anatomy, that fear is realized by way of the malfunctioning of the game, as we watch the house fall into glitches and fragmentation, the purpose of the home falls away and we’re left with an uncanny feeling of home-but-not-quite.

Meanwhile, the frame of the VHS cassette and the trope of audio cassettes inform this unhomliness, as they continue to degrade. What starts as a reference to the natural decay of magnetic tape – audio hiss, visual tracking – turns into the central scary element of the game, as each tape’s distortion and shriek becomes worse and worse. What is in the back of your mind during the first playthrough – god these tapes are terribly loud—oh it’s just hiss – is enacted in later playthroughs as static, high pitched yells, distorted speech, and even otherworldly breaking-in of a second voice without explanation are added. By the end, you find a tape recorder that, when pressed, just emits a static-drenched scream that goes on and on and on. Yes, Anatomy is real Noise.

But this is also what is most scary about the game, to me, who was absolutely cringing and terrified at 3 PM when I played it. Every tape felt like a necessary dare, and as I put it in the tape player to continue the narrative, I was horrified at what it would playback. Not because I expected a murder or gore or anything like that, but because the mutation of the medium of audio and video cassettes felt real, material, and visceral to me. As data is unnerving because it feels ghostly, physical data like tape reels and cassettes are unnerving because they can contain anything, and what they do contain carries the trace of the real. The trope of the snuff film, for instance, is so haunting because on each tape, we expect to find the smallest speck of blood, the trace of the scene itself. The digital in comparison feels clean.

I’m reminded here of the New French Horror, which personally is a bit too much for me to watch regularly. But films like Martyrs hit the same way Anatomy does, albeit through very different methods. New French Horror lays out for its viewer the expectations they should have: these films are violent, unflinching, and unfair. Anatomy does this with its tapes: expect to be viscerally upset not by content, but by sound, and expect nothing but more distortion. In that way, both schools emphasize the body – we are of course most embodied when we are uncomfortable – and both schools emphasize the horror of continuance. We can choose to stop either experience, and we know that if we do we’ll be spared discomfort and really lose no closure or explanation. However, we keep going, and, despite their extreme quality and accomplishment (and both are quite wonderful, particularly Anatomy) what New French Horror and Anatomy both ask by the end is “Why? Why did you finish me?” And this might be the most terrifying question of all.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Videodrone: Hacking and Leisure

(Hi! Sorry for the lateness of this piece, but I hope it’s worth it. Due to odd screenshot glitches in both games, these are fair-use-esque grabs from GIS; if you’d like them taken down, just contact me and I’ll be happy to.

Also please consider donating a few bucks at www.patreon.com/hegelbon. Big stuff in the works for donors!)

A friend recently asked me what there was to write about videogames. Well, more specifically he asked what – outside of advocating for videogames as either neo-therapeutic moments in our ever-instrumentalized day or as art – we could even say about videogames that would be worth writing in an essay. Obviously it’s an important question for me, though I’ve hitched my wagon to this art star despite an industry-wide turn toward subjectivizing the game experience, reading it as a way to achieve selfhood or actualization. But the subject is a subject for another column, perhaps next week’s.

What I’m interested in here is taking a moment to consider my friend’s question seriously. Obviously my answer to “what would you write about besides art?” is “There’s other stuff anyone would want to write about?” but let’s ignore that for the moment. I think there’s good reason to attempt to find an intelligible sphere for videogame discourse outside of the dusty sphere of aesthetics if only to hedge against the troubling instrumentalizing of fun as work-lite. Defend, say, No Man’s Sky as important post-stress decompression and it may seem like a powerful blow for self care; but self care in and of itself is a way to justify non-work activities as productive non-labor. Get your rest so that you can work better; find a hobby that supports your career; only take as many breaks as refresh you, so that you don’t get lazy. You get the idea.

Again, I am glossing this a bit quickly, but if I keep complaining about self care, I’m never going to get to 868-HACK or Uplink, and I really want to get to both games badly, in large part because they offer a third way option for conceptualizing the “use” of videogames. Specifically, they imagine the videogame form as a way to represent the scope and language of the digital, providing metaphors of digital existence by way of hacking simulators. As we’ll see, the form these simulations take are radically different, but I think tend to the same basic conclusion: that hacking as a phenomenon represents the imbrication of play and work that the digital represents, producing a kind of backdoor response to self care narratives that has little to do with high art, and more to do with casual gaming.

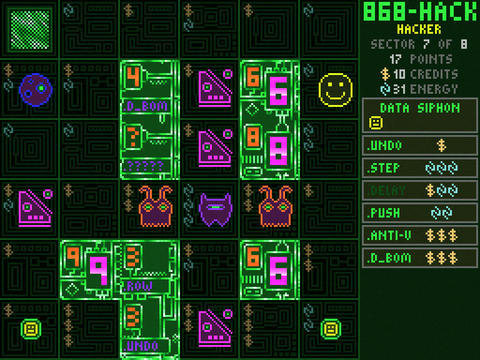

868-HACK is an iOS game that, like Verreciel and A Dark Room, is at once complex conceptually and simple in form. The game basically pits you as a hacker with no real narrative arc or motivation other than, well, hacking a system full of aggressive counter-measures. In this way, its plot resembles older ATARI and early arcade games like Defender or Joust, in which the plot of the game takes a backseat to the variety of enemy types and their particular movesets and attack patterns. (As a side note: This isn’t so different from the classic board game tropes found in chess, though the quicker repetition and introduction of points obviously differentiates the arcade game from the chess game.)

Like these games, 868-HACK introduces powerups that are made available when the player chooses to hack particular nodes in the system they’re navigating. These hacks introduce new enemies along with power-ups or points, and each enemy has to be strategically handled. As I began the game, I assumed I could just blast through my enemies and, ultimately, that was really, really dumb. By the time I actually beat the first level of the game, I had realized that you need to play the various viruses and defense programs step by step, as they respond in real time to your avatars steps. In this way, 868-HACK is a strategy game, one in which you need to balance profit (in points) with survival mechanisms (powerups) in an effort to beat 8 consecutive levels and gain new powerups.

If you’re thinking that 868-HACK sounds a bit like an arcade game in its own right as opposed to the complex systems we’re used to discussing here, you’re not wrong. Much like Ikaruga, 868-HACK is about learning a series of simple moves that add up into a complex series of challenging combinations. And this is where I think its indexical relation to hacking itself shines through: there’s nothing particular fanciful about the action of 868-HACK outside of your character’s smiley face avatar and the appearances of your enemies. Mostly, it is a repetitive, procedural romp through a digital set of obstacles – almost more a task than a game, something to kill time on a train. Or similar to the series of surveys available for filling out “in your spare time” for profit. Mindless, fun, and deeply dissembling.

Uplink follows this same trend in a much more ambitious form. Not narrative exactly, though with those elements certainly there, Uplink follows your character as they join a subterranean company of elite hackers, hired by multinational companies to sabotage, steal, and otherwise distort digital data, as well as the lives of some unfortunates that get in their way. The user interface of Uplink is graphically lenient, as it focuses largely on the massive map of the world populated by nodes that you can run your “Gateway” through in order to elude the authorities. When you aren’t on this screen, you’re clicking through files, copying, deleting, bypassing security, and keeping an eye on a clicking counter that alerts you to the authorities’ tracking progress. In short, you really do nothing but the very stressful work of a hacker, at least a hacker in the world of Uplink.

And really, it doesn’t so much matter if this is how a hacker operates in the real world. Like 868-HACK, Uplink is indexical to the feeling of working, operating, and existing in a totalized digital world, being reduced to a series of connections, clicks, and time limits. And while the game is really fun – I played it unadvisedly for four hours straight last night, getting caught and having my handle retired twice in the game’s frustratingly efficient permadeath – it’s also exhausting and stressful. In fact at the end of my playing session last night, I felt tense, stiff, stressed and ready to be anywhere but my computer.

And that’s the point, I think. Both Uplink and 868-HACK are engrossing and fun as videogames on their own merits, but what they seem to do best is represent the link between fun and work that late capitalism has slipped into our everyday life so seamlessly. Self care can be very important if you’re trying to help a friend stop pursuing self-defeating or dangerous behavior. But the merging of gaming with efficiency – speed running; achievements; complaints about “time to beat” being incommensurate with cost – and psychological preparation for “productive” labor – consider the push to beat games in order to play the next game coming out, on repeat, forever – put videogames in a complex relationship with capital’s push toward profit. This is not least of all due to their digital connections, their ties to the machines we use every day to remain so productive, and this is what these hacking simulators reveal so effectively.

So do I think 868-HACK and Uplink are important pieces of art? No, but I do think they are important social documents that put the lie to the instrumentalization of leisure time. And ultimately, to answer our earlier question, I think that’s something worth writing about.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Videodrone: KHOLAT

(Hi all! As a quick reminder, the Patreon is up and running at www.patreon.com/hegelbon . If I can get to 200 dollars a month, I will write reviews on as many of the Metal Gear series as I can – so donate! Thanks sincerely to all who have; it’s so appreciated.)

So, fortunately for you, I won’t be doing the all-caps spelling of KHOLAT all article long. Just for the sake of reference, the game is officially KHOLAT not, as I will be spelling it, Kholat. Cool? Cool.

Kholat is a first person horror game that can’t properly be called a “survival” horror game, really. A lot of negative reviews of Kholat on Steam emphasis this pretty insistently, and stress to any potential buyers that this game is one of the dreaded Walking Simulators we True Gamers have been hearing so much about. I’m sympathetic to their concerns, honestly, as the actual threats in Kholat are not really threatening so much as perplexing at best and irritating at worst. But Kholat is also not really a walking simulator, as simply walking without a plan leads you up against an impasse quickly as well.

Keep reading

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark Souls III: Irina, Eygon, Cruelty and You

((Hello! And welcome to the first of possibly three Videodrones this week. This is a guest piece by the excellent and incisive Jack Caulfied, aka @sadnesstweets on twitter. It’s wonderful stuff, and if you’d like to read more, he publishes on medium.com at https://medium.com/@sparks.falling.

As a reminder, the patreon is at www.patreon.com/hegelbon -- any little bit is more than appreciated!))

Dark Souls is a great series for tracing tropes and archetypes. There are all kinds of characters in whom you can recognise antecedents from previous games, dynamics and relationships that replicate themselves across the series. Today I want to focus on a pair of characters in Dark Souls III, Eygon and Irina (both ‘of Carim’), that I think are representative of a particularly interesting and omnipresent motif.

There’s a lot to the motif, which makes it difficult to sum up concisely. There is always a saintly victim figure, treated with a strange admixture of religious devotion and vicious abuse. The figure clearly has an important role to play in the series’ spiritual world (they are frequently fire keepers, and failing this, fulfilling an overtly spiritual role as, for example, the pilgrim Thea in the first game does), but this spiritual power does not translate into worldly power — in fact, seemingly the opposite.

(Anastacia after her magical revival)

These characters are almost always disabled, in some sense. Dark Souls III’s fire keeper is blind, as is Quelaag’s sister in the first game (and the Maiden in Black, from Demon’s Souls); Anastacia is mute; even the quite physically capable Darkmoon Knightess, who otherwise is something of an exception to the archetype, is said to be seriously deformed beneath her armour. The doll from Bloodborne appears to be literally an inanimate object brought to life. Further, when the player is able, through magical means, to ‘cure’ these disabilities, they are not met with any great praise for doing so. The fire keeper is unwilling to see; Anastacia is unwilling to speak.

These saintly sufferers are always women. I don’t intend this as a complaint about the series’ treatment of female characters; these games are hardly short on capable women, from Eileen the Crow to Sieglinde of Catarina to Lucatiel of Mirrah. But it is certainly a detail worth noting, firstly because the notion of passive suffering as saintly purity recalls a long history of depictions of women, and secondly because the second party in this dynamic, who, as mentioned, fulfils a role somewhere between devotee and persecutor, is always a man.

This is where it seems best to list the pairings of characters that I think most clearly represent the motif: Petrus and Rhea of Thorolund; Lautrec of Carim and Anastacia of Astora; Gehrman and the Doll; and of course, Irina and Eygon of Carim. Garl Vinland and Maiden Astraea from Demon’s Souls, while serving as clear visual and thematic inspiration for Irina and Eygon, do not appear to match the abusive dynamic under discussion here.

So, Eygon. You first meet him waiting outside a dark, locked cell. Inside the cell is Irina. Inquiring about this, you hear from Eygon that she is ‘a lost cause. Couldn’t even become a fire keeper. After I brought her all this way, and got her all ready. She’s beyond repair, I tell you.’ Immediately you see the strange dynamic at play here. Eygon is seemingly both Irina’s captor and, on some level, on her side. He strikes a note of hostility usually reserved not for a relationship of mutual antagonism but for a hopelessly embittered intimacy.

Being a good diligent soul, you find another way into the cell and speak to Irina herself. She is in a dark place. ‘The dark surrounds me,’ she says, ‘nibbles at my flesh. Little creatures, they never stop biting. So please, hold out your hand, and touch me…’ In one of the most affecting moments in the game, you do. And the moment of intimacy seems to make things better for at least the time being. The dark things give Irina some respite. Concurring with her guardian-captor, she declares herself ‘unfit to tend the flames’ but offers to assist in your quest all the same.

(A moment of quiet respite with Irina)

‘How very quaint, pitying creatures that are beyond help,’ Eygon sneers. ‘Very well. I’m sick of looking after her at any rate.’ The same bitterness, but then: ‘I am allied to you as long as you ensure the girl’s safety. And only for that long…’ The exact relationship between Eygon and Irina is, like much of these games’ lore, shrouded in obscurity. Are they blood relatives, past lovers, or simply strangers thrown together by Eygon’s knightly duty to protect Irina? Considering the way in which he mixes malicious insults with a serious concern for her safety, some combination of the two latter scenarios seems likely. As time goes on, we will see just how seriously he takes his terms.

Back at Firelink Shrine, your base of operations, you learn that Irina, too — perhaps ironically given her fear of the dark — is blind. She requests that we bring her divine tomes written in braille. For now, Eygon is nowhere to be found, seemingly glad to have foisted his ward on us. Returning the requested tomes to Irina allows her to teach you new miracles, a school of magic broadly focused on defensive and healing effects.

Eventually Eygon returns ‘to see how she’s getting on.’ You never actually see him check on her. In fact, throughout the whole game Eygon and Irina are almost never actually beside one another, and Irina only once (as we will see later) even refers to Eygon’s existence. ‘This cesspool of doddering oldfolk and degenerates,’ Eygon continues, ‘She must fit in perfectly here.’ Clearly more than anything, he has come to gloat.

Like most subplots in these games, there are a couple of ways this can end. The branching point relates to a pair of divine tomes quite unlike the others, and the question of whether you should learn the miracles from them. Upon being presented with these tomes, Irina warns us they are ‘forbidden’ and mentions again the ‘little creatures that nibble at me in the darkness…’ Meek, subservient, and accustomed to abuse, Irina, of course, does not outright refuse. She leaves the issue entirely in your hands.

The more positive ending for Irina, and, I suspect, the one vastly fewer players achieved, involves avoiding the miracles from these tomes altogether, and simply learning everything she can teach you from the regular, un-profaned tomes. At this point, with no subsequent reappearance from Eygon, Irina finally takes up the mantle of fire keeper. Her warnings against the dark tomes, though timid, were taken seriously. Though fragile, with her boundaries and her dignity finally respected she was able to flourish.

This, as I have said, is not the ending most players actually achieved.

(Irina as fire keeper)

The miracles from the ‘profaned’ tomes are different from the rest. They focus more on wounding and sabotage than medicinal or defensive effects. Their effects are alarming. One spell turns fallen corpses into exploding traps. Another summons a swarm of insects — ‘Little creatures, they never stop biting.’ It ought to serve as a warning but doesn’t. Irina teaches you the spells — what else can she do?

When you next return to the shrine, Irina is nowhere to be found. Her usual place sits empty. Perplexed, you go hunting. A little way outside, you find her — and a very angry, very hostile Eygon. ‘This knight of Carim does not forgive betrayal. Even a broken woman deserves her dignity…’ Here is Eygon, constant verbal and perhaps physical abuser of Irina, defending her dignity. From you.

There’s something to be said for a story that shows you a monster, then surreptitiously leads you into following in his footsteps, even surpassing him. Rescued from one who would abuse her trust, Irina found herself under the questionable protection of another who did the same.

Eygon cannot be reasoned with. When he’s dead, Irina is once again terrified, talking about the ‘little creatures’ and begging to be touched. You reach out a hand, but she doesn’t seem to recognise the touch, continuing to beg as if you were not there. You don the gauntlets stripped from Eygon’s corpse and do the same again. This time she recognises the touch. ‘Oh, you again,’ she says, ‘touch me, one last time. And kill me, as you promised you would.’ This is the one moment in which Irina acknowledges the existence of Eygon, and here it is evidently because she believes herself to be talking to him. Could she have been so afraid of him that she would not even dare discuss him with another?

With nothing else left to gain, you fulfil the request.

( Eygon’s usual demeanour)

It’s a distressing conclusion, not only because of its violence, but because it seems on some level to validate Eygon’s extreme and seriously abusive protectiveness. Was Irina better off in that cell than in your care? Was a life in the dubious custody of one who seemed to despise her for her weakness, and specifically threatened her life, the best she could hope for? In what context was the promise of death made? Did she want to die, to escape either the shame of failure or the pain of Eygon’s mistreatment? This being Dark Souls, there are no simple answers to these questions.

The clearest messages one can take from such a bitter conclusion, I think, are an awareness of abuse as something facilitated by power imbalances, not only by caricatured monsters; the fact that the worst horror a person can experience may be inflicted by those who ostensibly care most about them; and the sad familiar story of a person moving from one abusive situation to another, the latter involving the very person they thought to have saved them from the first. Above all, what’s most admirable in this story is an acknowledgement of (yet not an excuse for) the disturbing inseparability of tenderness and cruelty.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Videodrone: Bastion

There’s a bit of a built-in problem to Videodrone’s wide focus, but it’s one that I think any videogame analyst is going to face. Namely, you’re going to have to go over already tilled ground. Some games are going to be relatively un-examined – Verreciel from last week was a great example – and most very new games are going to be blank slates, outside of “should I buy this” style rating guides. So there’s definitely uncharted waters. But that doesn’t really free me from talking about games that a lot of people have written about. Games like Bastion.

Bastion is a textbook example of a game – like Braid or Cave Story – that encourages critical analysis off the bat. These games are independently produced, but with an eye toward playability. They don’t have the conceptual difficulty or mechanical frustration we saw in our iOS games, nor do they aim for the polish of a Triple-A title like a Call of Duty or a Final Fantasy. Generally low-res in spirit if not always in fact, and premised on simple mechanics that hearken back to older platformers, these indie games basically enter the market first because they are tremendously fun to play, and then second because beneath the playability, there’s some deeper artistic or philosophical statement.

For Bastion, the playability comes as an update of Zelda-style top-down platforming, as the camera swivels to a 2.5 person level, diagonally revealing the depth of the level while maintaining the spirit of the top-down spectrum. And like the Legend of Zelda that I’d argue inspires Bastion most, the game involves a lot of hack-and-slash, using ranged and up-close weapons to destroy enemies, surrounding areas, plants, etc, etc. So, the game at its core is about finding secrets, beating colorful enemies, and collecting shards that “rebuild” the Bastion, the central hub of the game that will ameliorate the “Calamity” that occurs just before the game starts.

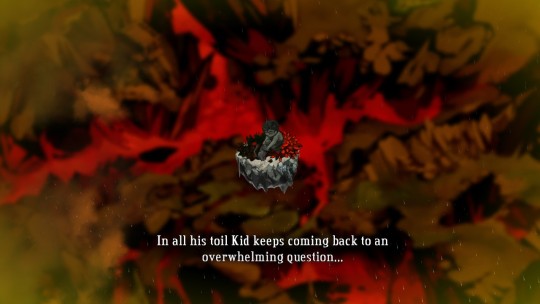

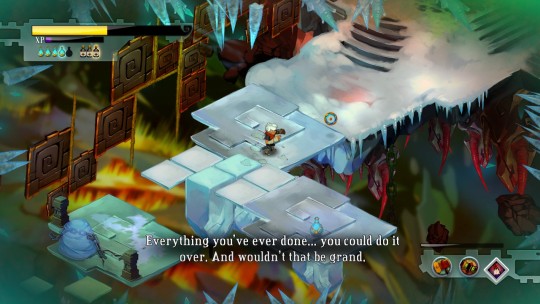

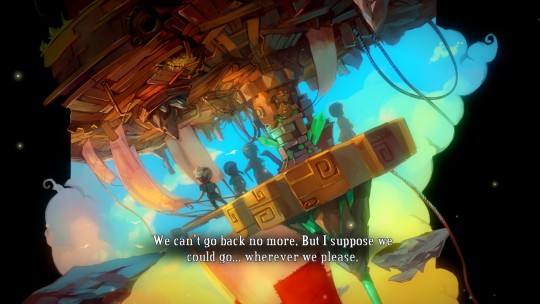

The Calamity is where the artistry of the game comes in. Your character – the Cormac McCarthian “Kid” – wanders through an already destroyed world, not entirely sure where to go except forward. As you walk forward, pieces of stone, grass, earth, etc fill in before you, creating paths through the levels and onward through the narrative as well. The Kid’s ability to recreate the destroyed land around him is coupled with The Stranger’s or Rucks’ narration, which overlays the entirety of the game, often in past tense. So the game, despite being played in real-time, takes on the appearance of a painting being constructed bit by bit (helped along by the game’s fully painted backgrounds): the Kid has already done everything you’re doing, and Rucks is retelling it as you perform the recursive actions of his story.

Confusing as this may be, the game reaffirms the logic in its final moments, after the Kid enters the last area of the game. Rucks stops telling the story of the game, and simply begins telling stories to his audience, who we finally discover is Zia, one of the few survivors of the Calamity. It is at this point in the story that the Kid gets choices – first, whether or not to save the man who “betrayed” the survivors, Zulf, and second whether to “Restore” the world before the Calamity or whether to use the Bastion to “escape” and move to a new world together with the other survivors. Notable also is the introduction of a second voice, as we finally hear Zia’s voice as well. At the moment of the first choice, we are shocked into a present moment, as opposed to a reflective past, and we realize the monolingual, retrospective nature of the game in a flash. Bastion, despite being a videogame with clear win-and-loss conditions, is just a long, winding story told by a master storyteller.

In this way, Bastion hits on some of the themes we’ve been uncovering a bit in past Videodrones, specifically the ways in which games ape or emblematize different ways of consuming media. Sunless Sea was like reading, Starseed Pilgrim like writing, and now Bastion is like storytelling. I think this is probably not a coincidence. Independent games, particularly, are becoming more and more aware of their strange relationship to art and are responding to their literary forbears in much the same way that games like Mario Paint or Rez responded to visual arts. After all, making and telling a story are interactive arts in their own way, if also solitary. The single-player videogame form gives the illusion of communion with others – your friends in the Calamity – but ultimately gives as much companionship as does a blank Word document. Or, in the case of the storyteller, an expectant audience.

The nature of audience here is important, too, as Bastion keys in on the anxiety of games like Hotline Miami and Spec Ops: The Line that the player is actually not doing a good thing. The Calamity, we find, was a weapon developed by Rucks and people like Rucks to kill of their ethnic enemy, the Ura, if need be. And the game directs you into killing off even more Ura in the interest of restoring the world that, it should be said, created the Calamity in the first place. It does not exactly inspire a lot of confidence, and the game is deeply aware of this. But Rucks first gives the Kid a sense of self-justification, and then follows with his own self-justification while he tells stories to Zia at the end of the game. It is only once the narrative is broken when the Kid is given choices that we realize Rucks is no omniscient narrator. All the flaws that are implied in the structure of his story are as much personal failings as narrative irony.

I think that this narrative irony is why Bastion is such a popular target for analysis. I’ll admit that I did not read up on what other people thought of Bastion, so it’s possible I’m retreading old ground. But like Rucks’ narrative as it loops back and forth – and there’s a very intriguing reading of the game I can make through the lens of Tristram Shandy if you want to get real crazy – new insights often appear to be older than they are, and vice versa. If Bastion teaches us anything about storytelling, it’s that it remains a communal practice even when the narrator is giving a monologue. The audience gives expectation, lives the story bit by bit, recreates it and ultimately extends beyond its boundaries, brick by brick. Whether this ends with an ethical revision of the narrative or the introduction of choice or both, Bastion certainly emblematizes the process, and it’s that that is so impressive about the experience.

Anyway, as Rucks might say, There’s more to say here, but ah well, we’re out of time. See ya for the next one.

1 note

·

View note

Text

VideoDrone: iOS

((Hi! Before we start, I want to announce some news. Since I’ve been really enjoying this project and have kind of settled into weekly posts more easily than I expected, I’m gonna give it its own home away from the blog associated with my Twitter. Don’t worry, I’ll reblog everything here too, so you don’t need to change your bookmarks, but VideoDrone will finally have a place of its own at video-drone.tumblr.com. The Patreon will remain the same, though hard and fast incentives that I think you’ll like are coming for backers, so consider putting even a dollar in to get those.

Anyhow, on with the show!))

I went on vacation last week and I was pretty sure I’d have to suspend VideoDrone coverage through til next week, which bummed me out. Luckily I had the bright idea to look into apps on my phone to see if there was anything there that might serve. And lo and behold, I discovered that the Apple App Store, which I just assumed was all expensive Final Fantasy ports and Candy Crush clones actually had a pretty vibrant community of smart creators. I expected to be hamstrung and what I found was that I couldn’t even hope to scratch the surface of mobile gaming in one VideoDrone. Good news for the both of us.

So today, I’m going to be talking about the two games I played and thinking about their status as explicitly mobile games. I’ll begin with the fairly well-recognized and loved “A Dark Room” and I’ll move on to the more recently released Verreciel (suggested by the always lovely @batemanesque on Twitter). Both of these games do double duty, critiquing gaming as a pastime on one hand while also actively interrogating the nature of the phone as device for communication and exploration. They are very much medium-specific art. In the spirit of this claim, I’m also typing this piece on my iPhone, so you’ll forgive any stylistic shifts intentional or otherwise. There will be no typos.

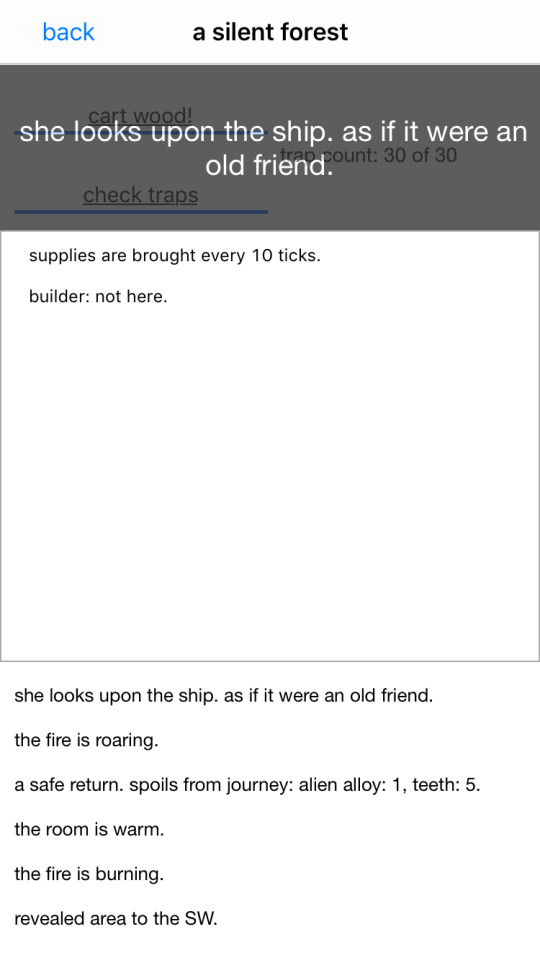

A Dark Room is the brainchild of Michael Townsend and was adapted to iOS from a browser based format by Amir Rajan. The game itself is pretty difficult to describe, but a couple of things off the bat: it’s entirely text based, and even the “map” upon which your character ventures out and the enemies that your character fights are rendered as common keyboard characters. The graphics, such as they are, are sub-386 computer, which frankly I think works better than unsuccessfully advanced graphics on an iPhone. That’s neither here nor there, though, as the game’s story-telling effectively uses the lack of graphical sophistication to its benefit, shifting to a part-narrative, part-roguelike explorer, part inventory management simulation that begins and, at least symbolically, ends with one basic command: stoke the fire.

The plot is straightforward enough to start. A wanderer stumbles into your room and collapses; you have to keep stoking the fire to keep her warm and alive. When she recovers she reveals she’s a builder and can build huts for other wanderers, given enough wood. So the game’s mechanic kicks in: press buttons to gather wood, check inventory to see if you have enough, build up your town. As the town grows, you get more and more buildings, along with a wanderlust. The builder urges you not to go off into the world, that death awaits you, but the game pushes you until you have to. And the world *is* full of danger, as water, food, and health all drop precipitously. Your explorations end with you dead all too often, and then you end up being brought back by the builder and her amulet.

Things get dark here as your villagers, who live in the huts you’ve built, never stop working, and you realize they are slaves. You also begin building up your weaponry to deal with the somehow decimated world around you. And at the point where you begin making bullets, the builder leaves you. You are left to conquer the world with your army of slaves, killing soldiers and villagers alike until you find a spaceship and fly away to another planet to begin again. (Indeed, a down and out swamp dwelling man suggests that he knew the builder too and failed her in much the same way you have).

Finishing the game in this way opens the same basic issues that we found in our previous reading of Hotline Miami and Spec Ops: The Line, namely that videogames are becoming more and more interested in making us feel ambivalent and even bad about our choices made in game. The world falls apart, you kill children, and the builder leaves, all of which seems like just part of the way the game progresses – what is the player supposed to do but build more huts, more guns, more water tanks for more expeditions?

Well, as the game tells you after beating the game once, you could build *no* huts. And this dramatically changes the game, as the builder does not travel her arc of anger and desertion, but instead becomes sick, needing to reach the stars. And without townspeople to help gather supplies, the name of the game is much less about overpowered expansion of empire, and more about quick raids for supplies and patient checking and rechecking of the wood pile. The game changes dramatically, in other words, to show the difference between being a warlord and being a lone person trying to help a friend.

A Dark Room cleverly breeds both the power and stress into these respective positions by way of it’s mechanics, wherein the player constantly clicks back and forth between the “fire” screen (which needs stoking the whole game) and the inventory management screen, constantly clicking button after button in timed sequence. Some critics have described this as akin to the neoliberal business trend of “flow,” in which a worker gets so into their task that they enter a state of zen-like space of productive time. For my money though, A Dark Room is much more conscious about the ways it divvies out its stress. The complicity with making more and more slaves to build bigger and better weaponry is tied to the fact that to do it alone would be brutally time consuming. Similarly the panic you get over losing, say, five food or whatever during the survival mode isn’t tied to Perma-death (which this game doesn’t have), but time. “I just died and lost 20 minutes” you might say, as if your email just crashed after penning a long draft.

This means that A Dark Room, in addition to being a gripping narrative experience, is an efficiency trap too, a well wrought critique and imitation of the phone you play it on. The game is fun often, and I really do recommend it to everyone, but the driving force of completing it is more just process justification -- one last tweak, one last task to finish. And when these tasks are lined up in a way that leads to dictatorial destruction, you start to see how such a philosophy could begin to make sense to a bureaucratically poisoned mind. Even alternatives seem outside the system until the system poses them, and much like our next game, Verreciel, the game relies on the pluck of the player to explore alternatives. It just also gives the player a comfortable medium -- their phone -- to make remarkably predictable moves. In the normal clicking back-and-forth why question the need for huts? You need more people to make the process easier; that's how apps work. You begin to see the logic and the critique.

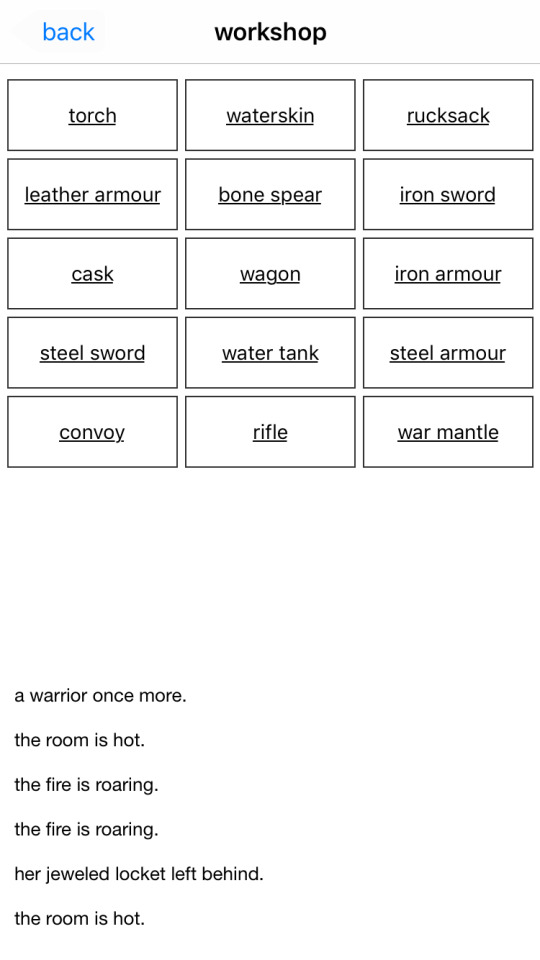

In Devine Lu Linvega's Verreciel, the ethics of the piece fall out almost altogether. While the game has its climax when your character literally puts out several suns, the purpose or motivation behind the character's action is pretty opaque. The main thing you are concerned about as a player is making your ship run, and your ship's console is, you guessed it, your iPhone screen. Effectively blurring the distinction between in-game action and controller, you may as well be pressing commands on your ship as you use the touch screen to link and control the thrusters, navigation, even the radio of your strange, complex ship.

The game itself is a bit buggy, and often this ends up being the best strategy guide for the game -- crash Verreciel and find yourself with the right collection of odd objects to complete your next task. But I don't really begrudge Linvega for this; the game is massive and experimental, wonderfully conceived and visually arresting without, again, trying to recreate console graphics that fall flat in the iPhone medium. Indeed, as the plot doesn't so much matter in Verreciel, the game encourages peaceful space flight and patient, often Jerry-rigged solutions to barely expressed technical problems. In other words, it's exactly like owning an early version of a piece of technology.

Verreciel, like A Dark Room, relies on atmosphere as much as it does plot or gameplay, encouraging an unconscious blending of iPhone and game until the interface becomes almost unnoticeable. For a space flight simulator, this makes Verreciel dreamy and immaterial, paced at a crawl that feels -- much like Sunless Sea did -- a veritable part of the game itself. It, and A Dark Room, aren't perfect games, but they get the idea of medium specificity, and what opportunities the iPhone provides for videogames. That both games end with dreamy fadeouts and recursion to the opening screen is notable as well, as they blur their status as games and apps. You don't "beat" Google Maps -- you get to the end and restart. Both games take the problem of replayability and essentially pose it as an inevitability of the form.

That there are iOS games that actually care about their medium is an encouraging thing, especially since they'll never be the money makers casual games like Angry Birds or Candy Crush are. These aren't really "on the train" games. But they are games that care about the device in which they're played, and as a result, they feel a lot like the early 8-bit experiments in expansion or the 16-bit freak out experiences in early computer gaming. They're trying something new, and it focuses on interface; in this way, I really do think iOS games are doing something markedly different than console or PC games. If they keep it up, they will be a serious part of the critical games landscape to come.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark Souls III: Siegward the Comic Hero

((Please welcome Jack C, our very first guest-writer! This is the first of a series on Dark Souls III, and deals with a blog favorite, Henri Bergson. Follow Jack at @sadness_tweets because he is great. Also, British spelling has been maintained to show respect to our friends due East))

People talk about Dark Souls like it’s all grim, self-serious dark fantasy. People don’t talk about how funny these games are.

Among the most beloved characters from the first Dark Souls was Siegmeyer, the jolly, doddering, faintly incompetent old knight of Catarina. Affectionately known as the onion knight due to his distinctively absurd armour, he was, appropriately enough, always ‘in a pickle.’ His role was to be found repeatedly by the player stuck behind one obstacle or another, to wait until they helped him out, and then to gently chastise them for the foolish risks they took in doing so.

He was one of several ways in which the game injected levity into what could easily have become an insufferably sombre game – but of course, he was subject to the same metaphysics as the player, and his jolly demeanour could not serve him well. After a side-quest involving his (identically dressed) daughter Sieglinde’s search for her father, the player encounters Siegmeyer in Lost Izalith, where helping him out has greater ramifications than before. Defeating the creatures that have him trapped without his help leads him to seemingly give up entirely, cursing his ‘inability,’ while letting him join in the fight leads to his death. His end is as grim as that of any of the game’s characters.

Henri Bergson, writing on the nature of the comic, states that ‘a comic character is generally comic in proportion to his ignorance of himself. […] A character in a tragedy will make no change in his conduct because he will know how it is judged by us; he may continue therein, even though fully conscious of what he is and feeling keenly the horror he inspires in us. But a defect that is ridiculous, as soon as it feels itself to be so, endeavours to modify itself, or at least to appear as though it did.’ The tragic figure, in other words, is locked in a forewarned but inevitable decline; the comic figure encounters obstacles and, insofar as it realises its own ridiculousness, attempts (probably quite unsuccessfully, thereby extending the farce) to reorient itself so as to progress.

Siegmeyer, though he met an end that one could only really describe as tragic, certainly seemed to be attempting this (failed) reorientation before his death. One always feels he deserves a second chance. So when in Dark Souls III a man shows up in an identical suit of armour, with an identical voice, and as perfectly sunny and bumbling a disposition, and calls himself Siegward, it is difficult not to be overjoyed. (Not surprised – reincarnations and uncanny echoes of the past are par for the course in these games). He greets the player with the same ‘Hmmm… hmmmmmm…’ as his predecessor did, and the same references to being ‘in a bit of a pickle.’ He has a new catchphrase too: ‘I’ve got to use my head and think.’

He is, once again, stuck, this time trying to figure out how a lift mechanism works so that he can reach the top of the tower and ‘talk some sense into’ the giant raining gigantic arrows down on the landscape. It’s a laughable idea, and yet the player (because of course, Siegward doesn’t do it himself) reaches the top of the tower and finds that it works. ‘I help anytime,’ says the giant, and becomes a sworn ally for the rest of the game.

A broken clock is right twice a day, right? Certainly Siegward isn’t looking very competent the next time we see him, sitting on a balcony halfway up the tower, having seemingly fallen off the lift. He looks out into the distance where a large, imposing fire demon paces around. He repeats his line about talking some sense into it, but wisely realises it won’t work this time. ‘He’s far too overheated. I’ve got to use my head and think.’

Cleverly, there’s no real way out of this situation for the player other than to fight the thing. Which is when something surprising happens: rebuking the player as always for their hastiness, Siegward actually joins in. He doesn’t hit too hard but can hold his own. After defeating the thing, absurdly, he sits down with the player and they share a toast (we keep a tankard of his personal ‘Siegbraü’ as souvenir), before he falls asleep, declaring it ‘the only thing to do really, after a nice toast.’ A broken clock, maybe, but Dark Souls III seems inclined to give Siegward the benefit of the doubt.

This, it seems to me, is the gaping absence in critical discussions of the Souls games’ tone. If there’s reference to humorous absurdity it is often treated as a side-effect of the games’ multiplayer systems empowering players to behave ridiculously on their own terms – but rarely does anyone mention the sheer number of joyously funny moments built into the games themselves.

We next find Siegward at the bottom of a well, naked, his armour having been stolen by Patches (another returning character and one whose trickster antics also attest to the games’ inherent humour). After returning his armour we find him in an area with a striking resemblance to one of the places in which he became stuck in the first game, making soup. The soup provides a health boost and a warm feeling. He repeats his little routine of initiating a toast and then falling asleep, with identical dialogue.

(For Bergson, the comic ‘consists of a certain mechanical inelasticity, just where one would expect to find the wide-awake adaptability and the living pliableness of a human being.’ Siegward’s identical actions in different situations fit the bill.)

After rescuing him from another prison in the next area, we reach the proper end of Siegward’s story and an important milestone in that of the game writ large. As we step into a large, intimidating throne-room to fight Yhorm the Giant, Siegward follows us in. He addresses Yhorm as an ‘old friend’ and speaks of upholding a ‘promise’. Siegward defeats this apparent old friend with comical ease. The player barely has to do anything, indeed barely can do anything as unlike Siegward they lack the proper equipment. Siegward, duty apparently fulfilled at long last, expires – seemingly suicide.

This all seems rather incongruous until we dig deeper. Reading the description of the Storm Ruler, the sword Siegward drops upon death after using it to defeat Yhorm, we find that Yhorm left it ‘to a dear friend before facing his fate’. Of course, then, this dear friend is Siegward. Suddenly his earlier insistence on talking sense into the giant atop the tower makes sense – poor, bumbling Siegward has some acquaintance with giants.

This lore excavation is all typical Souls and interesting in its own right but not the point of this essay. The point is that, like its predecessors, Dark Souls III is doing something quite novel with its use of comedy – in the world of video games, all I could really think to compare it to would be the Metal Gear series’ potent blending of absurdity with profundity. I could as easily have used the example of Solaire from the first game to illustrate the same phenomenon. The thing that I think we see in the game’s depiction of Siegward is this: a strong vein of comedy in an overwhelmingly dark setting, and one that refuses to stick to the role of just comic relief.

Rather, Siegmeyer, Solaire and Siegward are heroes. They fail in absurd ways, and in Siegward’s case succeed in ways almost as incongruous, but absurdity is the rule in this universe and their ridiculousness ultimately makes them more like us. Who, in playing these games, hasn’t been stumped by the most superficially negligible obstacles, or through sheer luck overcome the most intimidating foes on the first try?

Comedy is an essential and frequently overlooked element of the Souls style, and is not merely employed as an occasional mood-lightener, but as the backbone of the narrative. This is a strain of comedy which, like all the greatest examples of the mode, on some level takes itself very seriously.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Videodrone: Sunless Sea

I didn’t really know what I was going to write about Sunless Sea until I lost my second ship to a dumb occurrence close to home. And all of a sudden, I realized I’d write about frustration.

Some clarification: Sunless Sea is, as best I can characterize it, a sailing simulator set in the world of the popular and longstanding browser-based game universe of Fallen London. I haven’t played Fallen London, so I have no idea how Sunless Sea jibes with that, but suffice it to say, the cruel and disinterested quality browser games have toward their audience transcends the genres and comes out clearly in Sunless Sea. If you’ve read a Videodrone before, you’ll know that this cruelty is where I got hooked.

But unlike a number of the other difficult games I’ve considered, Sunless Sea trucks more in the science of frustration than anything else. It’s closer to the “Is it a Word Processor or a Game” genre of Starseed Pllgrim, but the game element is stronger here. The game itself, as best I can describe it, is focused on exploration as a mechanic, formally concerned far more with the slow unfolding of dangerous exploration than with combat or acquisition. In this way, it’s a bit like Stardew Valley. But again, the difficulty is far ratcheted up, and the game effectively taunts you into taking the hardest route: if you switch to “Merciful Mode” (a mode that allows for periodic saves that aren’t auto-saves), you lose an item that has no purpose in the game other than marking your ability to not give in. I mean come on, have you heard a better incentive?

The game isn’t kidding when it gives you the warnings in the above image -- you go through your first captain quickly. And the instant you (I) feel confident about your (my) second captain, they’ll die too. The game is nothing so much as a love story to the early forays into narrative videogaming like Zork, or Sierra and Lucasfilm adventure games. Brutally list based, largely premised on making choices that have set risk percentages, and privileging narrative, Sunless Sea bares no small resemblance to those early attempts at producing a “virtual novel.” Unlike these early attempts, though, Sunless Sea has two new things going for it: first, it balances difficulty, graphics, and narrative expertly; and second, it is self-reflexive.

The first bit might be the easiest to explain. In Sunless Sea, you’re forced to balance hunger, fuel, and sanity. Your hunger is salved by supplies, which are used more or less quickly depending on how many “zailors” you have on hand at any given time, or if you have a chef as an officer. Your fuel decreases quickly, but all the more quickly if you have your lights on. And if you don’t have your lights on (and even if you do), your fear ticks up. Get to zero supplies, and your crew eats itself. Get to zero fuel and your boat stops and you drift aimlessly. Get to 100 terror, and you’ll go mad.

As you continue through the game, you dock at ports in order to gain reports (which you can sell to interested parties), finish quests (criminal or otherwise), and simply see what’s up. All of these moves net you money, through which you can buy ship upgrades, a nicer home, something for your family (which you can choose to produce or not), and, most importantly, more fuel and supplies. But the exploration of the islands is its own reward, producing pages of narrative driven by choices that have very real outcomes, good and bad. You can lose crew, supplies, fuel, terror, etc, or you can gain treasures and plot movement. It’s all a roll of the dice.

Ultimately, it’s this roll of the dice that makes Sunless Sea interesting. The narrative is fairly generic for the type of game it is: a vast, terrifying London, infested by Lovecraftian demons; a quest to “zail” across the ocean against terrible odds. But the various stories on the islands flesh out the world tremendously and in surprising ways. What could become a steampunk free-for-all turns into a fairly considered, cautious, and always frustrating attempt to inch further out into a dangerous world. And when you die, you don’t forget, personally, the stories, even if your new captain might not know them. So what ends up being tremendously frustrating -- “Ah dammit my captain died I spend like four hours building that one!!” -- quickly turns into a redirected focus -- “I wonder how quickly I can recoup my losses and discover more about what’s going on at Hunter’s Keep or The Chapel of Lights.”

To put it bluntly, Sunless Sea knows full well that it’s a pain in the ass. The company who made it has the Beckettian nom de plume of “Failbetter Games” -- it’s not like there’s a lot of dissimulation going on. But the triumph of the game is in convincing its player that it being a slow, cautious slog that can unravel in one bad decision is a feature, not a mistake. The balance of the mechanics keeps the difficulty high, but the paced mystery of the plot, premised on decisions the player makes (and often regrets), or by the quality of the ship, or by the knowledge of one’s officers appear randomized in outcome, but not in significance. In other words, while I may not uncover some secrets in one iteration of the game because of bad luck or poor choices, in a second iteration, I know those secrets still exist and might come through in a roll of the dice.

Sunless Sea, therefore accomplishes an allegory of reading that I feel is more successful than any interpretative account of Starseed Pilgrim’s approach to writing. Exploration, dead ends, stories that require seven, eight, a dozen revisitings -- this is all familiar to those of us who’ve worked through a tough read. The consequences of the game encourage reconsideration and experimentation. The game’s mission structure forces both directed and randomized stops across a map that, to begin with, is blacked out entirely. The self-reflexivity of Sunless Sea is, essentially, that it gets to say “This is for your own good” to its players, and regardless of the player’s patience with the game, it’ll be right.