Hello, I'm heather. I'm an user experience designer and researcher. I like learning by doing and going down rabbit holes.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Quote

The trouble with the internet, Mr. Williams says, is that it rewards extremes. Say you’re driving down the road and see a car crash. Of course you look. Everyone looks. The internet interprets behavior like this to mean everyone is asking for car crashes, so it tries to supply them.

Evan Williams in interview with NYT

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Today I came across some scrappy videos I made for fun many years ago. Now they're tiny capsules of a past life. My colleague calls this type of video momentshowing, which I quite like. Makes me want to do more, so this is my publicly stating that I’m going to.

0 notes

Quote

Consider the hummingbird for a long moment. A hummingbird’s heart beats ten times a second. A hummingbird’s heart is the size of a pencil eraser. A hummingbird’s heart is a lot of the hummingbird. Joyas voladoras, flying jewels, the first white explorers in the Americas called them, and the white men had never seen such creatures, for hummingbirds came into the world only in the Americas, nowhere else in the universe, more than three hundred species of them whirring and zooming and nectaring in hummer time zones nine times removed from ours, their hearts hammering faster than we could clearly hear if we pressed our elephantine ears to their infinitesimal chests. Each one visits a thousand flowers a day. They can dive at sixty miles an hour. They can fly backwards. They can fly more than five hundred miles without pausing to rest. But when they rest they come close to death: on frigid nights, or when they are starving, they retreat into torpor, their metabolic rate slowing to a fifteenth of their normal sleep rate, their hearts sludging nearly to a halt, barely beating, and if they are not soon warmed, if they do not soon find that which is sweet, their hearts grow cold, and they cease to be. Consider for a moment those hummingbirds who did not open their eyes again today, this very day, in the Americas: bearded helmet-crests and booted racket-tails, violet-tailed sylphs and violet-capped woodnymphs, crimson topazes and purple-crowned fairies, red-tailed comets and amethyst woodstars, rainbow-bearded thornbills and glittering-bellied emeralds, velvet-purple coronets and golden-bellied star-frontlets, fiery-tailed awlbills and Andean hillstars, spatuletails and pufflegs, each the most amazing thing you have never seen, each thunderous wild heart the size of an infant’s fingernail, each mad heart silent, a brilliant music stilled. Hummingbirds, like all flying birds but more so, have incredible enormous immense ferocious metabolisms. To drive those metabolisms they have race-car hearts that eat oxygen at an eye-popping rate. Their hearts are built of thinner, leaner fibers than ours. Their arteries are stiffer and more taut. They have more mitochondria in their heart muscles—anything to gulp more oxygen. Their hearts are stripped to the skin for the war against gravity and inertia, the mad search for food, the insane idea of flight. The price of their ambition is a life closer to death; they suffer more heart attacks and aneurysms and ruptures than any other living creature. It’s expensive to fly. You burn out. You fry the machine. You melt the engine. Every creature on earth has approximately two billion heartbeats to spend in a lifetime. You can spend them slowly, like a tortoise and live to be two hundred years old, or you can spend them fast, like a hummingbird, and live to be two years old. The biggest heart in the world is inside the blue whale. It weighs more than seven tons. It’s as big as a room. It is a room, with four chambers. A child could walk around it, head high, bending only to step through the valves. The valves are as big as the swinging doors in a saloon. This house of a heart drives a creature a hundred feet long. When this creature is born it is twenty feet long and weighs four tons. It is waaaaay bigger than your car. It drinks a hundred gallons of milk from its mama every day and gains two hundred pounds a day, and when it is seven or eight years old it endures an unimaginable puberty and then it essentially disappears from human ken, for next to nothing is known of the the mating habits, travel patterns, diet, social life, language, social structure, diseases, spirituality, wars, stories, despairs and arts of the blue whale. There are perhaps ten thousand blue whales in the world, living in every ocean on earth, and of the largest animal who ever lived we know nearly nothing. But we know this: the animals with the largest hearts in the world generally travel in pairs, and their penetrating moaning cries, their piercing yearning tongue, can be heard underwater for miles and miles. Mammals and birds have hearts with four chambers. Reptiles and turtles have hearts with three chambers. Fish have hearts with two chambers. Insects and mollusks have hearts with one chamber. Worms have hearts with one chamber, although they may have as many as eleven single-chambered hearts. Unicellular bacteria have no hearts at all; but even they have fluid eternally in motion, washing from one side of the cell to the other, swirling and whirling. No living being is without interior liquid motion. We all churn inside. So much held in a heart in a lifetime. So much held in a heart in a day, an hour, a moment. We are utterly open with no one in the end—not mother and father, not wife or husband, not lover, not child, not friend. We open windows to each but we live alone in the house of the heart. Perhaps we must. Perhaps we could not bear to be so naked, for fear of a constantly harrowed heart. When young we think there will come one person who will savor and sustain us always; when we are older we know this is the dream of a child, that all hearts finally are bruised and scarred, scored and torn, repaired by time and will, patched by force of character, yet fragile and rickety forevermore, no matter how ferocious the defense and how many bricks you bring to the wall. You can brick up your heart as stout and tight and hard and cold and impregnable as you possibly can and down it comes in an instant, felled by a woman’s second glance, a child’s apple breath, the shatter of glass in the road, the words I have something to tell you, a cat with a broken spine dragging itself into the forest to die, the brush of your mother’s papery ancient hand in the thicket of your hair, the memory of your father’s voice early in the morning echoing from the kitchen where he is making pancakes for his children.

Brian Doyle , an essayist and novelist, died on May 27, 2017

Via Scott Baker

0 notes

Quote

Even the best experts in a field, no matter how good their intentions, can’t reliably anticipate the consequences of what they’re doing on their own. The world is too complicated.

Dr. Kevin Esvelt, talking about gene drives and open research

1 note

·

View note

Quote

the ability to talk the same language has gone. More and more we are divided into communities of concern, each side can ignore the other side and live in their own world. It makes you less of a nation because what binds us together is the pictures in our heads, but if those people are not sharing those ideas they are not living in the same place anymore.

From the documentary Best of Enemies

0 notes

Quote

he story of the biological clock is a story about science and sexism. It illustrates the ways that assumptions about gender can shape the priorities for scientific research, and scientific discoveries can be deployed to serve sexist ends. We are used to thinking about metaphors like “the biological clock” as if they were not metaphors at all, but simply neutral descriptions of facts about the human body. Yet, if we examine where the term came from, and how it came to be used, it becomes clear that the idea of the biological clock has as much to do with culture as with nature. And its cultural role was to counteract the effects of women’s liberation.

The foul reign of the biological clock

1 note

·

View note

Quote

We don’t miss what we don’t see. The thought, “what if I miss something important?” is generated in advance of unplugging, unsubscribing, or turning off — not after. Imagine if tech companies recognized that, and helped us proactively tune our relationships with friends and businesses in terms of what we define as “time well spent” for our lives, instead of in terms of what we might miss.

How Technology Hijacks People’s Minds — from a Magician and Google’s Design Ethicist

0 notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A New App Illuminates the Hidden Histories of Everyday Places

"I’m really interested in how content—be it art, writing or something else entirely—can reach people when they’re not expecting it, rather than them having to seek it out," Cole explains to The Creators Project. "Tours can be great experiences, for example, but we have to set aside time for them whereas I wanted to explore serendipitous discovery with minimal effort from the users. I was also intrigued by narratives of place and how we access them. There might be numerous depictions of any given place, both visual and written, but how might we discover them whilst there, and how might they change our perception of that place?"

File away for the post-Jane’s Walk blues

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The gap between the food we cook and the food we talk about has never been larger. Culturally, it’s the same gap that exists between The Americans—the brainy FX spy show that seems to have nearly as many internet recappers as viewers—and shows like the immensely popular and rarely discussed NCIS. Breathless blog posts about the latest food trends can feel like certain corners of music criticism, pre-poptimism, when writers would obsess over the latest postrock band that was using really interesting time signatures while ignoring the vast majority of music people listened to on the radio. The food at Allrecipes is the massively popular, not-worth-talking-about mainstream.

If You Are What You Eat, America Is Allrecipes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“You are, as a class of human beings, responsible for more pure raw time, broken into more units, than almost anyone else. You spent two years learning, focusing, exploring, but that was your time; now you are about to spend whole decades, whole centuries, of cumulative moments, of other people’s time. People using your systems, playing with your toys, fiddling with your abstractions. And I want you to ask yourself when you make things, when you prototype interactions, am I thinking about my own clock, or the user’s? Am I going to help someone make order in his or her life, or am I going to send that person to a commune in Vermont?

There is an immense opportunity—maybe it’s even a business opportunity—to look at our temporal world and think about calendars and clocks and human behavior, to think about each interaction as a specific unit, to take careful note of how we parcel out moments. Whether a mouse moving across a screen or the progress of a Facebook post through a thousand different servers, the way we value time seems to have altered, as if the earth tilted on its axis, as if the seasons are different and new.

So that is my question for all of you: What is the new calendar? What are the new seasons? The new weeks and months and decades? As a class of individuals, we make the schedule. What can we do to help others understand it?

If we are going to ask people, in the form of our products, in the form of the things we make, to spend their heartbeats—if we are going to ask them to spend their heartbeats on us, on our ideas, how can we be sure, far more sure than we are now, that they spend those heartbeats wisely?”

Paul Ford, 10 Timeframes

1 note

·

View note

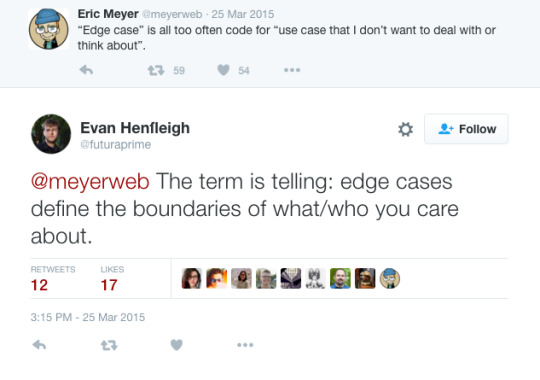

Photo

“Edge cases define the boundaries of who [and] what you care about. They demarcate the border between the people you’re willing to help and the ones you’re comfortable marginalizing. That’s why we’ve chosen to look at these not as edge cases, but as stress cases: the moments that put our design and content choices to the test of real life. It’s a test we haven’t passed yet. When faced with users in distress or crisis, too many of the experiences we build fall apart in ways large and small.”

Started reading Design for Real Life tonight. So far, so very good.

1 note

·

View note

Link

”Techies is a portrait project focused on sharing stories of tech employees in Silicon Valley.

We cover subjects who tend to be underrepresented in the greater tech narrative. This includes (but is not limited to) women, people of color, folks over 50, LGBT, working parents, disabled, etc.

The project has two main goals: to show the outside world a more comprehensive picture of people who work in tech, and to bring a bit of attention to folks in the industry whose stories have never been heard, considered or celebrated. We believe storytelling is a powerful tool for social impact and positive change.”

c/o Kristy Tillman

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

When I watched the video below it reminded me of this quote from Zainab Salbi:

"Do you know that people fall in love in war? and go to school, and go to factories and hospitals and get divorced and go dancing and go playing and keep life going, and the ones that are keeping that life are women."

0 notes