𝓻𝓮𝓼𝓮𝓪𝓻𝓬𝓱 𝓻𝓮𝓼𝓱𝓪𝓻𝓮 𝓪𝓷𝓭 𝓸𝓻𝓲𝓰𝓲𝓷𝓪𝓵 𝓬𝓱𝓪𝓻𝓪𝓬𝓽𝓮𝓻 𝓯𝓸𝓬𝓾𝓼𝓮𝓭 𝓫𝓵𝓸𝓰

Last active 4 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Theatrical trailer for House / Hausu (1977) dir. Nobuhiko Ōbayashi

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

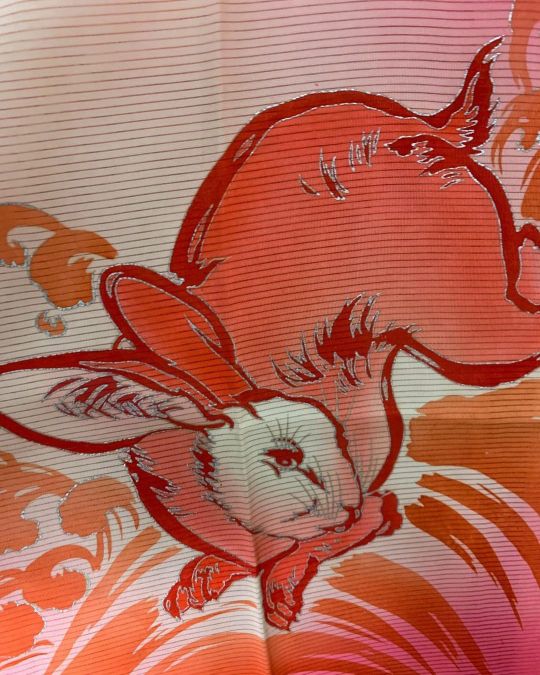

Vivid sunrise hues for this unsual summer weave juban, depicting rabbits on the waves (a pattern association symbolizing seafoam)

523 notes

·

View notes

Photo

from the Japanese movie “Five Women Surrounding Him”, 1927

142 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Using prophecies in fantasy without making eyes roll

Good ol’ stand-bys, ubiquitous fantasy tropes, are difficult to avoid. And sometimes we don’t want to avoid them. Goddammit, sometimes you just need a good, solid prophecy to write the story your want to write.

“It’s not my fault all these other people before me have written prophecies, too!” you say.

And you’d be right. Unfortunately, they did. So us modern-day writers have to live with the it. So what do you do when you want or need to use a well-worn trope?

Know the trope. Make it your own.

Know that, no matter what you do, some readers will still hate it.

But you can’t make everyone happy, right? So let’s get started.

How-to guidelines from our predecessors

Prophecies in fiction have been used countless times. But there are reasons why we continue to use them. And while you don’t want to completely copy how it has been done before, we can all learn something from the basic form of real and fictional prophecies.

1. Prophecies are often vague and general

The language and phrasing used in prophecies, because of its important and symbolic nature, tends to go for sounding mystic and grand over sensible and utilitarian. This language achieves its poetic goal, but as a price, the meaning can be allusive, vague, or even seem contradictory.

A man named Jerry will kill a man in a fight on the corner of 3rd and Main on the fifth of January, 3820.

On the dawn of winter in a forest of gray, when one life dims, another remains.

One of these actually gives you some useful information. The other could mean a vast array of different things at any point in time, but technically applies to the same situation. One of them (though poorly) reads more like something you’d find in a piece of fiction.

2. Prophecies are often misinterpreted

There’s likely to be disagreement on the meaning of any yet-to-be-fulfilled prophecy. If it’s well-known, then common folk might take it to mean one thing, while the wealthy another. The well-educated might take it to mean one or two (or three or a thousand) things, while the uneducated take it to mean another. If there are two prominent schools of thought, then people might passionately disagree about the meaning. It’s possible that none of these interpretations are true.

‘Tis the nature of vague and metaphorical language.

The culture of your world will influence how people treat the prophecy. Conversely, the prophecy and its interpretation might have a huge impact on the culture, government, or religion of your world.

3. Prophecies are given in context

In the example above about the murder in winter, with no context that “prophecy” means basically nothing. Part of what creates nuances in interpretation of prophecies is variations in the understanding of the prophecy’s context.

Upon the rebirth of the emperor, the dark messenger will be slain; the eagle will conquer the land.

In this sample, very little is made clear when there’s no context. We have no reason to care, let alone believe, what these words are trying to convey. But say that our myths tell the story of a vanished young emperor who would someday reappear to take his throne, that the messengers of evil are immortal, and that the eagle is symbolic of peace…

It all starts to make a bit of sense, doesn’t it? Any alteration in context, however, could vastly change the meaning.

Prophecies don’t stand alone. They only work within their context. They aren’t created in a vacuum and they are not understood in a vacuum. Creating the vibrant world that surrounds your prophecy will go a long way to making it interesting and important.

4. Prophecies require a prophet

Why do people believe the prophecy? Why don’t they? When implementing a prophecy into your world, you need to pay attention to how people receive its message and ensure that that belief has a sensible backing.

A prophecy came from the mouth (or pen) of a prophet. If the people of your world totally buy into the words of this prophecy, then there needs to be a reason. What made this prophet reliable?

What not to do: There was this old woman and everything she said was totally batty…all except this one thing. This one thing will definitely be absolutely true, so help me, God.

Like any aspect of culture, the “why” factor is important. Why do people believe the prophecy? Why has it survived so many years? Or perhaps people don’t believe the prophecy…so why is that?

Consider Nostradamus. He’s a pretty infamous prophet, even though only some of what he said every seemed true (and almost entirely in retrospect). For the most part, when you mention him, people will kind of laugh it off. It’s mostly a joke. However���his words might also be true! But it’s best not to put all your money on it.

How are the words of your prophet generally received? How will this affect how your Important Prophecy™ is viewed and understood by the people?

“This Important Prophecy™ is believed because my story needs it to be believed,” is not a good reason. So make sure it runs deeper than that.

Pitfalls to avoid

1. Using a prophecy as a matter of course

Your prophecy should have a very integral part in your story and world. Using a pointless prophecy or using one just because you think, since you’re writing fantasy, you probably should, are one-way tickets to eye-rolls.

Like any trope, if you’re sticking it artlessly into your story, then you doing the trope and yourself a disservice. Every element you choose to include in your story should drive it forward, should deepen your conflict or characters. No inclusion should be made flippantly. Be sure that if you’re including a prophecy, you use it to its full potential.

2. Making it too simple or mundane

If you’re doing it right, then your prophecy will be super important to your story. And if it’s super important, you’re going to want it to be super interesting. If a dull, run-of-the-mill Chosen One prophecy is, unironically, what your story hinges on, then you’re likely going to get some eye-rolls and, worse, readers who put down your book.

3. Going for too much

On the other end of the spectrum, prophecies that are convoluted or require the ten-page backstory to put into context are likely going to take too much attention away from your actual story. Prophecies tend to focus on one (general) event. It can cover a few facets of this one event, but if you try to outline too much you risk detracting from the here-and-now or getting too far in over your (or your character’s) head.

Things to consider

Is the fulfillment of the prophecy a mystery even to your reader? Or does the story give the answer, leaving the path to the fulfillment to be the mystery?

Is your prophecy immutable? Is it Destiny and it will come true no matter what anyone does?

Is the prophecy self-fulfilling? How do the characters’ knowledge of the prophecy affect events? How might their ignorance of it?

How does the fulfillment differ or align with the expectations held by the characters?

Did the prophet speak of their own freewill, with true foreknowledge, or were they a vessel for a deity, or some supernatural being?

How was the prophecy passed down to the present? Was it done so flawlessly, or might there have been translation, oral, or interpretation errors that happened along the way?

How widely accepted, or known, is the prophecy among the common people?

How common are prophecies in general? Does this one stand out in some way? If so, how and why?

Does the prophecy give away an outcome, or does it simply set up a situation?

How detailed is your prophecy and how have those seemingly specific details been misinterpreted?

How certain is anyone that they understand the prophecy?

If the prophecy proves to be false, how does that element find resolution within the structure of the narrative? (i.e. if you placed great importance on the prophecy with the intention of pulling the rug out from under your reader, how are you going to resolve the situation to keep them from feeling cheated?)

What do you think about the use of prophecies in fiction? What are some of your favorites or least favorites?

Happy writing!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

• Free Thai Movement

The Free Thai Movement (Thai: เสรีไทย; RTGS: Seri Thai) was a Thai underground resistance movement against Imperial Japan during World War II.

In the aftermath of the Japanese invasion of Thailand in December 1941, the regime of Plaek Phibunsongkhram (Phibun) declared war on the United Kingdom and the United States on January 25th, 1942. Seni Pramoj, the Thai ambassador in Washington, refused to deliver the declaration to the United States government. Accordingly, the United States refrained from declaring war on Thailand. Seni, a conservative aristocrat whose anti-Japanese credentials were well established, organized the Free Thai Movement with American assistance, recruiting Thai students in the United States to work with the United States Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The OSS trained Thai personnel for underground activities, and units were readied to infiltrate Thailand.

Phibun's alliance with Japan during the early years of war was initially popular. The Royal Thai Army joined Japan's Burma Campaign with the goal of recovering their historical claims to part of the Shan states, previously surrendered to the Burmese Empire in the Burmese–Siamese wars and subsequently annexed by the British following the Third Anglo-Burmese War. They gained the return of the four northernmost Malay states lost in the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909, and with Japanese mediation in the Franco–Thai war they also recovered territory lost in the Franco-Siamese War of 1893. However, Japan had stationed 150,000 troops on Thai soil, and as the war dragged on, the Japanese increasingly treated Thailand as a conquered country rather than an ally. Although the United States had not officially declared war, on 26 December 1942, US Tenth Army Air Force bombers based in India launched the first major bombing raid, which damaged targets in Bangkok and elsewhere and caused several thousand casualties.

Meanwhile in the United States, under Seni’s guiding hand, and the leadership of Gen. William Donovan’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the “Free Thai” movement was born. Seni brought young Thai student volunteers from universities across the United States together into a Free Thai command, which was to serve under Donovan’s OSS. The Free Thai agents were among Thailand’s best and brightest. They set aside promising academic programs at Harvard, Cornell, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and elsewhere in favor of difficult military training and uncertain futures. Following training by the OSS, many volunteers undertook lengthy and dangerous treks from China and Indochina to make contact with supporters opposed to the Japanese presence. For months, the Free Thai forces worked to infiltrate their homeland. Many were captured, killed, or simply went missing.

Finally, in October 1944, the OSS Detachment in Szemao, China, received a radio message from Free Thai agents in a Bangkok safehouse. Thereafter, other agents were dispatched into Thailand by submarine, seaplane, and airdrop. The heroism and ingenuity of the Free Thai forces, working hand-in-hand with the OSS, set the stage for important intelligence collection. The agents provided critical support to Allied military operations in Southeast Asia and ensured Thailand’s post-war independence. In June 1944, Phibun was forced out of office and replaced by the first predominantly civilian government since the 1932 coup. Allied bombing raids continued, and a B-29 raid on Bangkok destroyed the two key power plants on April 14th, 1945, leaving the city without power and water. Throughout the bombing campaign, the Seri Thai network was effective in broadcasting weather reports to the Allied air forces and in rescuing downed Allied airmen. The new government was headed by Khuang Aphaiwong, a civilian linked politically with conservatives such as Seni. The most influential figure in the regime, however, was Pridi Banomyong (who was serving as Regent of Thailand), whose anti-Japanese views were increasingly attractive to the Thais.

In the last year of the war, Allied agents were tacitly given free access by Bangkok. As the war came to an end, Thailand repudiated its wartime agreements with Japan. Unfortunately, the civilian leaders were unable to achieve unity. After falling-out with Pridi, Khuang was replaced as prime minister by the regent's nominee, Seni, who had returned to Thailand from his post as leader of the Free Thai movement in Washington. The scramble for power among factions in late 1945 created political divisions among the civilian leaders that destroyed their potential for making a common stand against the resurgent political force of the Thai military in the immediate postwar years. Postwar accommodations with the Allies also weakened the civilian government. As a result of the contributions made to the Allied war efforts by the Free Thai Movement, the United States, which unlike other Allied countries had never officially been at war with Thailand, refrained from dealing with Thailand as an enemy country in postwar peace negotiations. Before signing a peace treaty, however, the United Kingdom demanded war reparations in the form of rice shipments to Malaya, and France refused to permit admission of Thailand to the United Nations (UN) until the Indochinese areas regained by the Thais during the war were returned to France.

Some famous members of the Free Thai Movement include; Queen Rambai Barni, widow of King Prajadhipok and nominal head of the Seri Thai in the United Kingdom, Prince Suphasawatwongsanit Sawatdiwat, Queen Rambai Barni's brother, a former Royal Thai Army officer, Thawi Bunyaket, Prime Minister of Thailand 1945, Air Marshal Dawee Chullasapya, and Siddhi Savetsila, later Air Chief Marshal of the Royal Thai Air Force, Foreign Minister of Thailand, Deputy Prime Minister of Thailand, and Privy Councillor to King Bhumibol Adulyadej.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

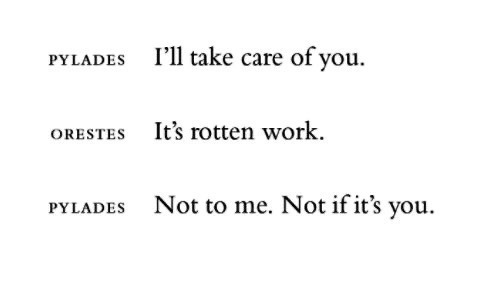

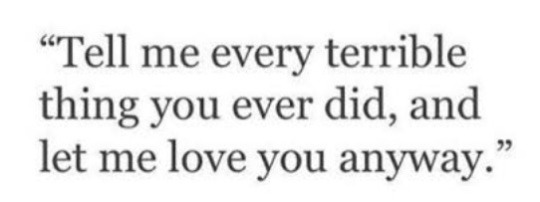

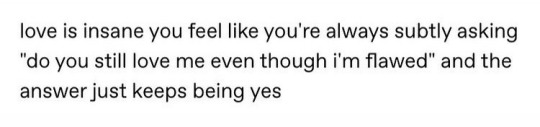

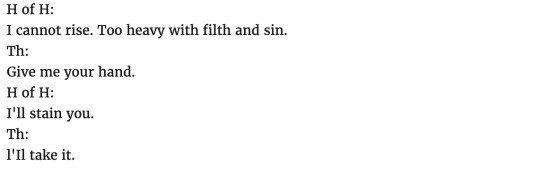

Love as Acceptance

Caitlyn Siehl // Leonard Cohen, "Anthem" // Rumi, "Bitterweet" // trans. Anne Carson, "Euripides" // Sade Andria Zabala, "Coffee and Cigarettes" // tumblr acct @/gayassnatural // Anne Carson, "H of H Playbook" // William Shakespeare, "Sonnet 116" // Clementine von Radics, "Mouthful of Forevers" // Toni Morrison, "Jazz"

49K notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese Battleship Ise sunk in Kure Harbor, Japan, 1945.

Photographed by aircraft from USS St. George (AV-16) and from USS Montpelier (CL-57), on October 14, 1945.

NHHC: 80-G-349909, 80-G-351361

U.S. Navy photo from the USS Montpelier (CL-57) World War II cruise book: link

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yukio Mishima, “Ordeal by Roses,” by Eikoh Hosoe

source

796 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nobuko Otowa as Princess Taema in “The Beauty and the Dragon” directed by Kōzaburō Yoshimura (1955)

975 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A group of eight yari-saya [spear sheaths] Edo period, 19th century

For single-headed and jumonji-form spears (yari), variously decorated in gold, black and red tataki-nuri.

42.5 cm., 16¾ in. high (the tallest).

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summer walks in nature. The Misty Pond of Villeneuve, 1908. Painter: Henri Biva, oil on canvas.

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

death and sensuality

Jusepe de Ribera, San Sebastián curado por las Santas Mujeres, 1621 / William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Dante and Virgil in Hell, 1850 / Peter Paul Rubens, The Death of Adonis, 1614 / Francesco Vanni, Saint Catherine Drinks the Blood of Christ, 1594 / William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Pietà, 1876 / Matthias Stom, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, 1640-1649 / Antoine Wiertz, The Greeks and the Trojans Fighting over the Body of Patroclus, 1844 / Nicolas Régnier, Saint Sebastián Tended by Saint Irene, 1625 / Peter Paul Rubens, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, 1613-14.

690 notes

·

View notes