I am a self-employed bookbinder working from my home studio in Somerset. I work to commission creating unique bindings on books using a variety of skills including: leather work, embroidery, metalwork and carpentry, and try to write as much as I can about it here!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

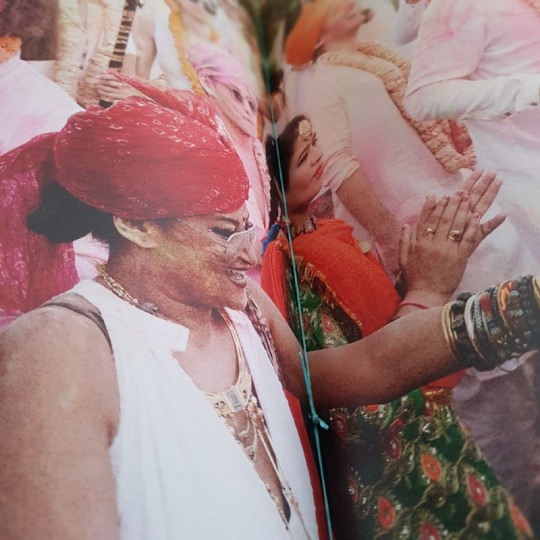

HOLI SALONI

Holi is a popular ancient Hindu festival, also known as the “Festival of Spring”, the “Festival of Colours” or “The Festival of Love” and is celebrated in March on differing dates each year to mark the arrival of spring, the end of winter and the blossoming of love. The annual event commemorates the triumph of good over evil, while also celebrating fertility, colour and love.

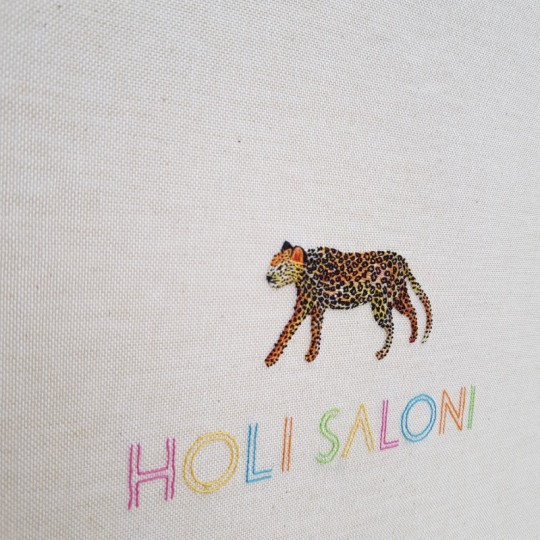

In 2019 I was commissioned by the fashion label Saloni, to make two identical bindings for photographs taken during this festival in India in 2018. Named "Holi Saloni" the festival was a celebration of Holi teamed with Saloni's exacting sense of colour, cut and imaginative collections. The brief set was to create two bindings with the below hand-embroidered design on the cover; the “Holi Saloni” title with a leopard above it.

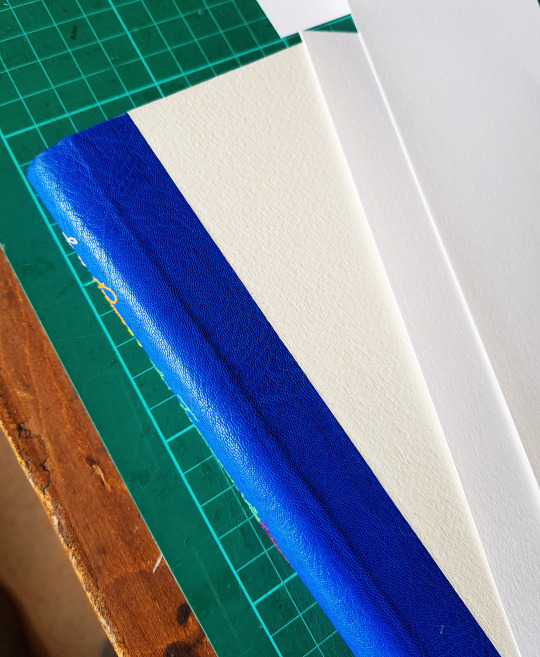

The bindings were to be covered in a neutral linen bookcloth that I ordered from Winter & CO, “WICOTEX® - Natuurlinnen 2041 - Tamar Cream Natuurlinnen”.

I decided the best method was going to be to work on the leopard cut-out off the book. As the bindings were going to be quite large, the linen book cloth was going to be difficult to embroider onto so this was to aid this part of the process to make it more manageable.

I cut out the leopard outlines from thinly pared pale yellow leather. The onlays were then painted with acrylic paint to build up a background colour.

I then selected a range of orange, yellow, cream and white threads and began to embroider the leopard cut outs.

I used tiny stitches, overlapping the colours to blend them together.

I worked little by little across the two leopards, working one colour at a time so that they were as similar as possible in appearance. I left the very edge of the leopard outline free of stitches, knowing that I would add these in once the leather cut-out was stuck to the linen covering cloth.

In order to make sure that I was going to sew the leopards black spots in the same pattern on both of the cut-outs I punched a series of holes through the paper leopard template where I wanted each to be. This was then placed on the reverse of the sewn leather onlay, and I marked through each hole with a marker pen.

I was then able to create the leopard’s black spots using the black spots I had marked on the reverse as a guide.

These spots were built up using a series of knots, creating clusters of dots to form a pattern all over the body of the leopard.

As with the base threads, the spots were also embroidered within the outer edge of the leopard shape, with the outer stitches to be completed once the onlay was stuck onto the covering linen cloth.

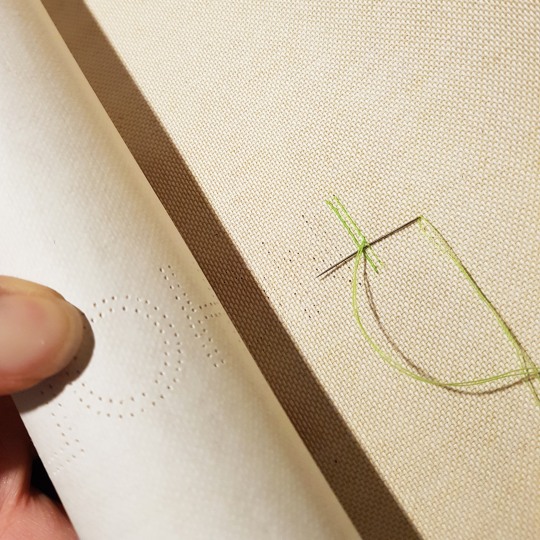

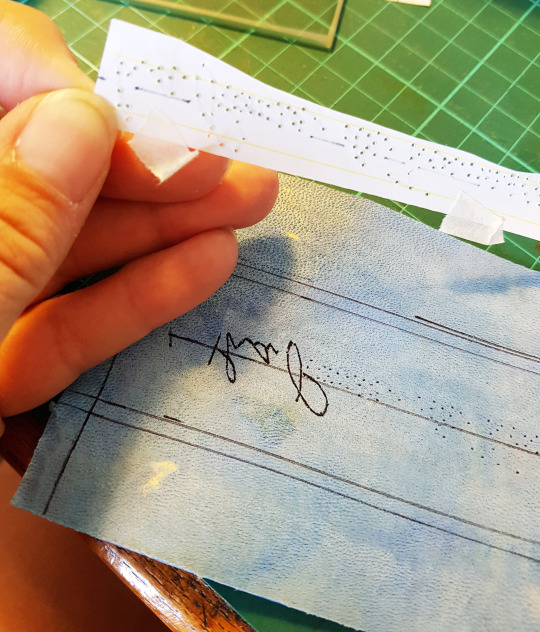

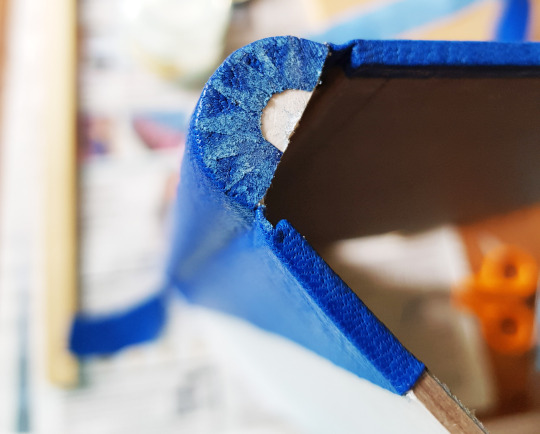

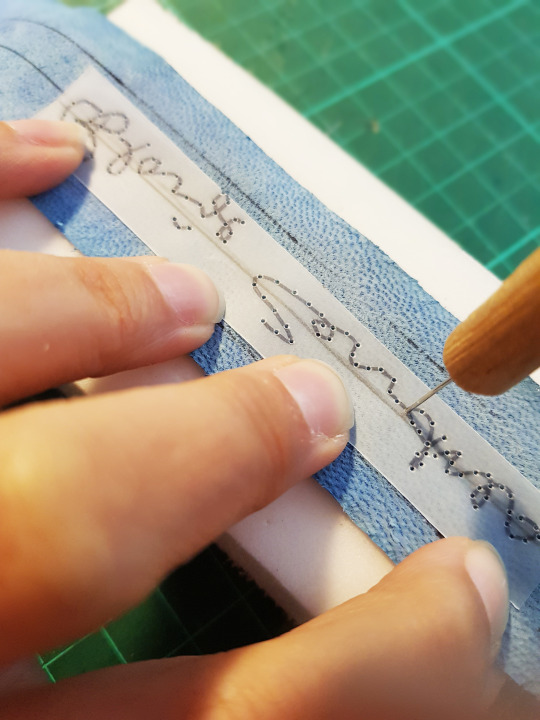

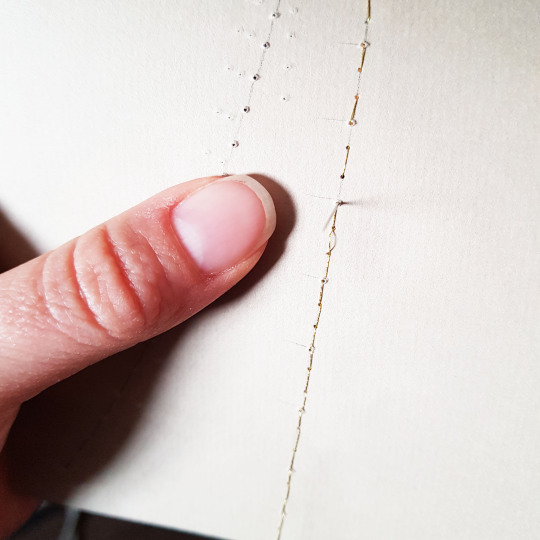

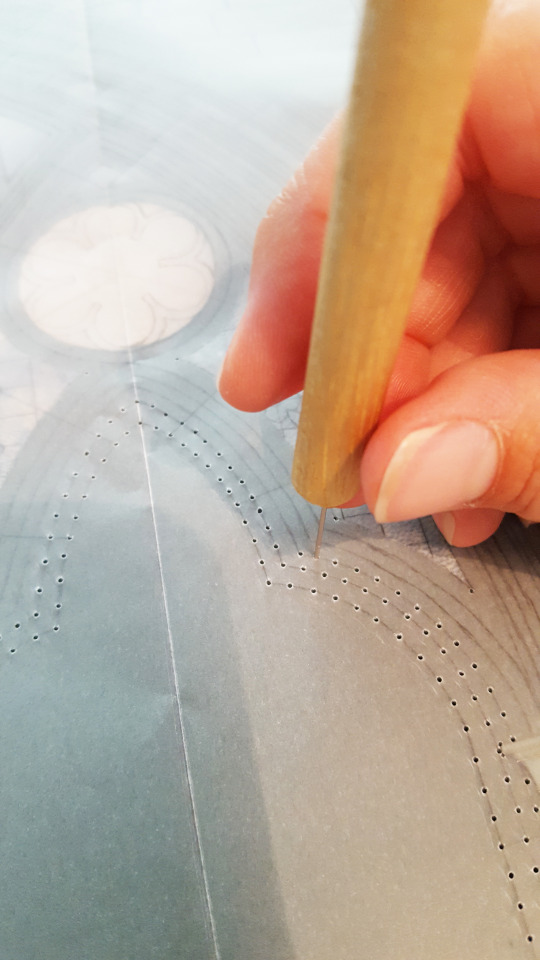

To correctly place the title onto the linen cloth for embroidering, the paper template was stuck down with masking tape in the correct position and the lines of the title letters were pricked through with a needle pricker. This marked where the stitches needed to go.

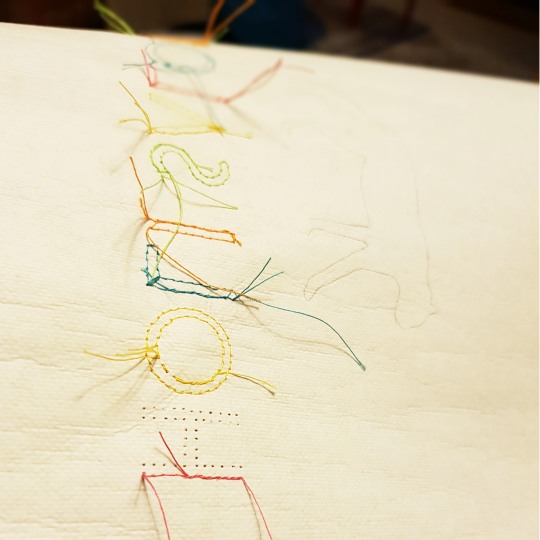

I matched the colours on the initial design to thread colours. The lines were then embroidered with a running stitch, and then I used a whipping stitch to consolidate the running stitch.

On the back of the linen cloth, the end of the threads were woven behind the stitches, and once I had done all of the stitching these were trimmed so no loose threads were present.

At this point I was able to stick the embroidered leopard cut-outs onto the linen cloth using PVA glue. I then finished off the tiny base stitches in the orange, yellow, white and cream threads and also finished the black dots around the circumference.

The back of the linen below shows what it looked like once all of the embroidery was complete.

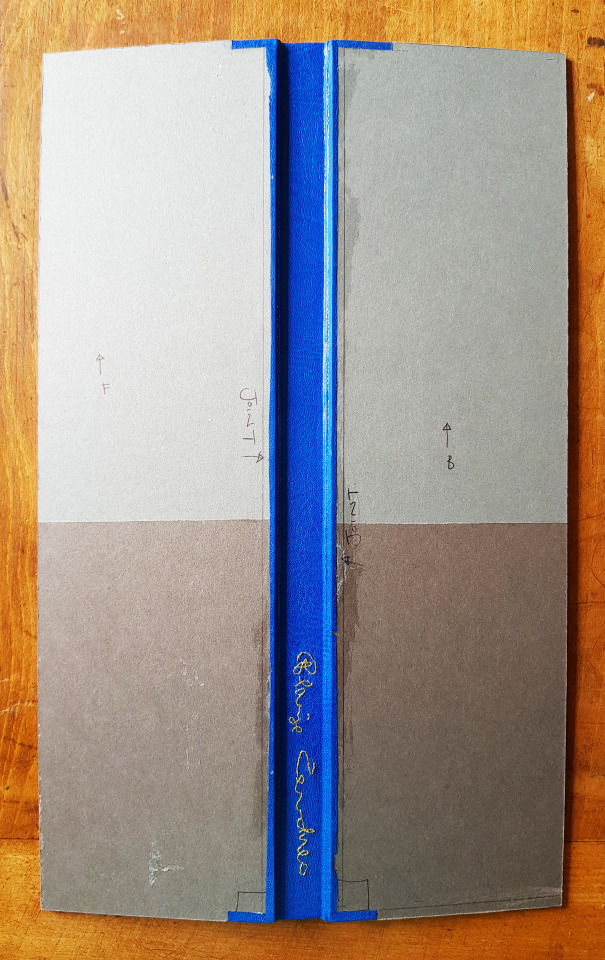

I next moved onto the construction of the outer cover. A case was made, sticking laminated boards and a spine piece to the linen cloth. The cloth was turned in and the inside of the boards were infilled and sanded flush. The back and front boards were then finished with a mandarin orange coloured paper stuck down as a doublure.

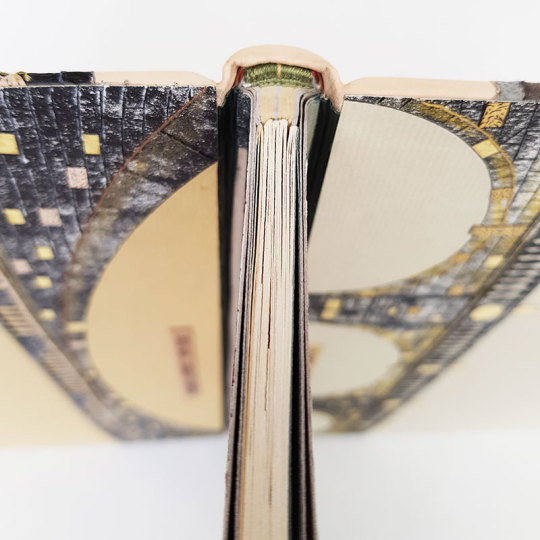

The plan was to sew each of the seventeen sections into the book using linen threads. I therefore needed to drill a series of holes through the spine section of the case to allow me to attach each section directly through it.

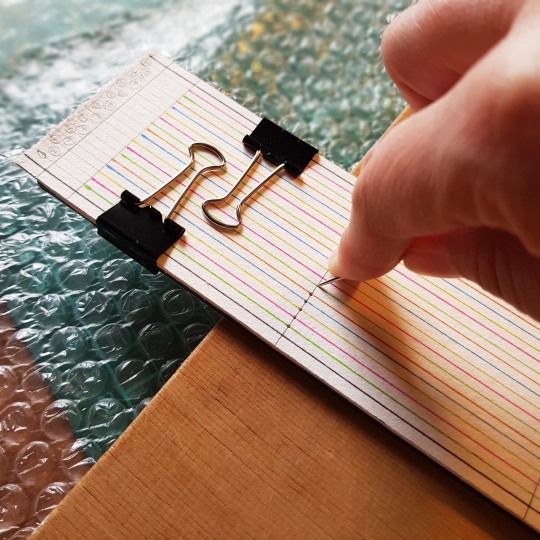

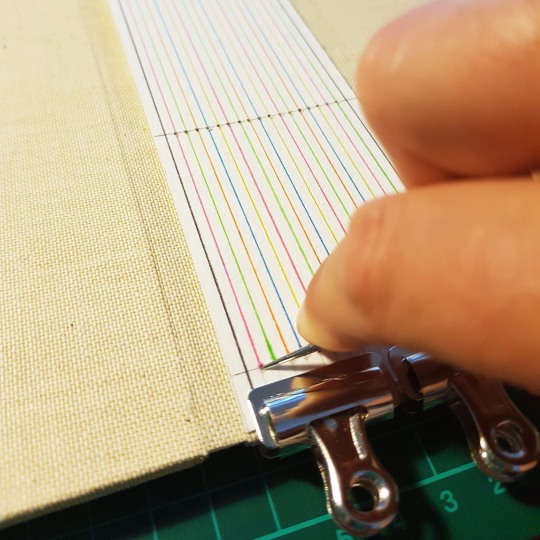

I made a template from card, with lines marked in the corresponding thread colour order.

This was then clipped to the spine section using bulldog clips and I marked a point at each of the holes using a bodkin. I then removed the template, and using a 0.8mm drill bit, drilled a hole at each of the points using my Dremel.

Section by section I then attached them onto the spine, making sure I pulled the threads as tightly as possible to keep the sections taught against the spine of the case.

The threads were ordered from Hilke Kurzke at Büchertiger. To get a good match for the five colours I largely ordered Crawford Threads (Orange Crush, Fuchsia , Autumn Yellow and Turquoise) with the final length being Lin Cable (Vert Clair).

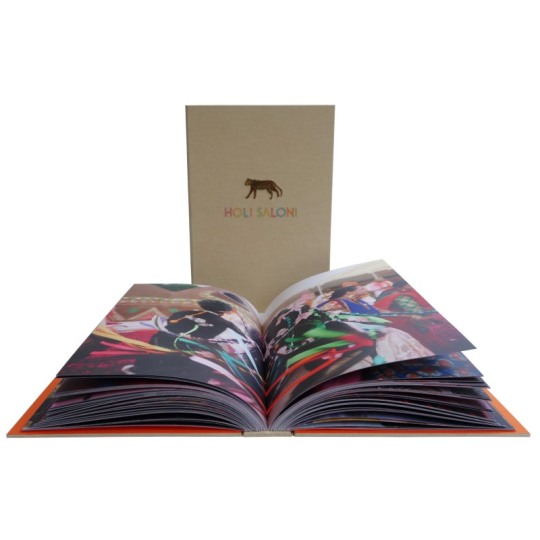

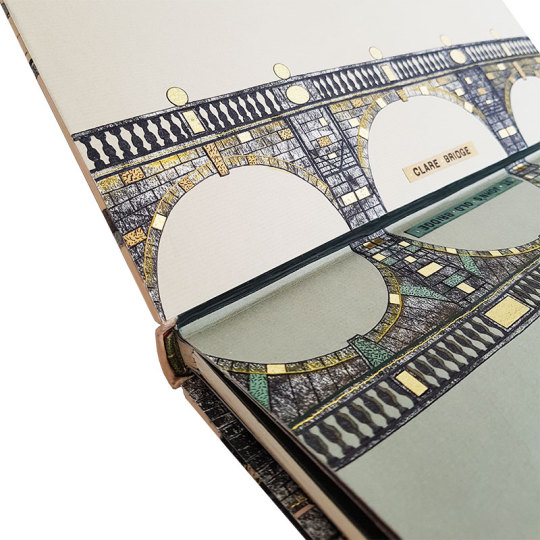

The following images show the completed book...

COVER AND SPINE DETAIL

THE BINDINGS OPENED NICE A FLAT USIGN THIS METHOD OF BINDING, ALLOWING THE PAGES OF THIS LARGE BOOK TO BE VIEWED WITH EASE

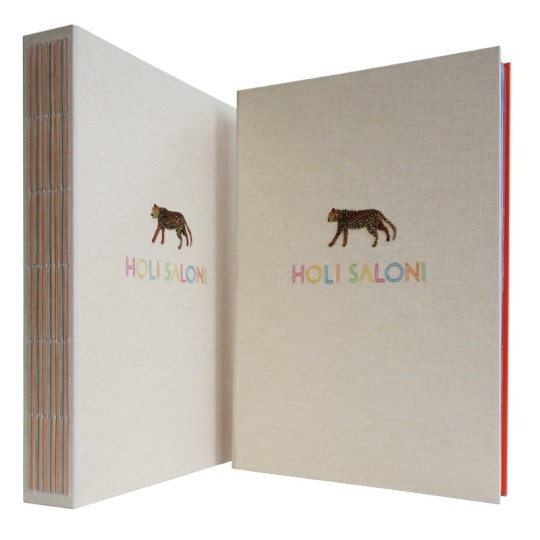

THE TWO IDENTICAL BINDINGS SIDE BY SIDE

DETAIL OF THE PAGES, WITH THE COLOURED THREAD TIED ON THE INNER FOLD OF EACH OF THE SECTIONS

#holisaloni#saloni#holifestival#festivaloflcolours#festivalofspring#festivaloflove#bookbinding#embroideredbinding#designbinding#embroidered animals#embroideredleopard#leopard

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

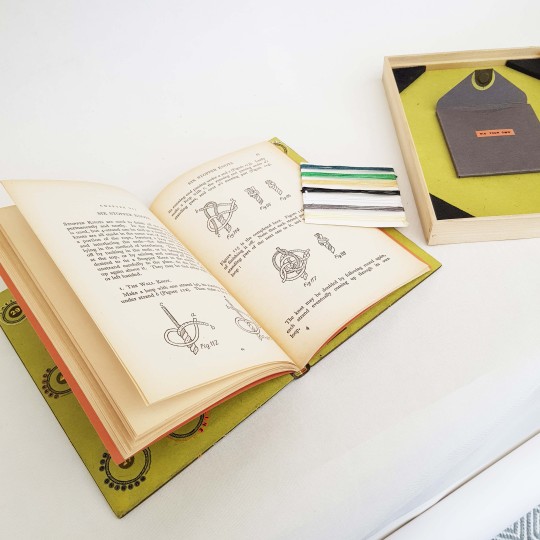

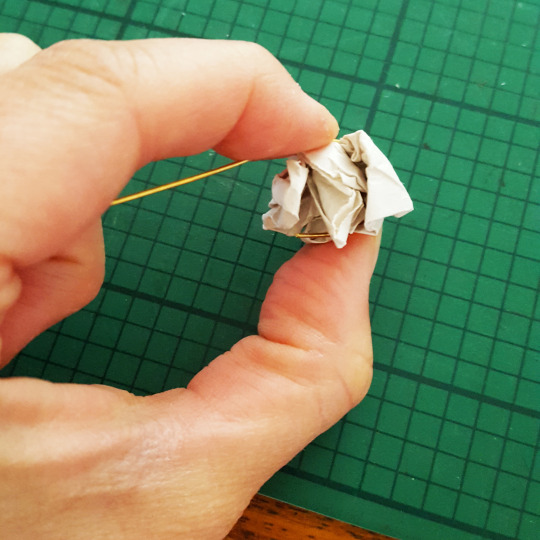

Music: Miniature Board

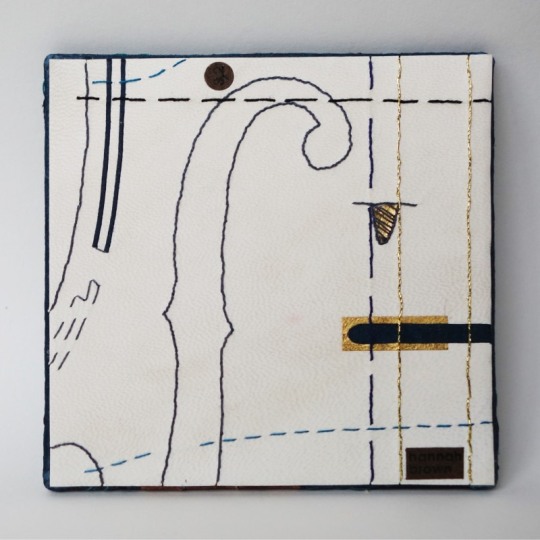

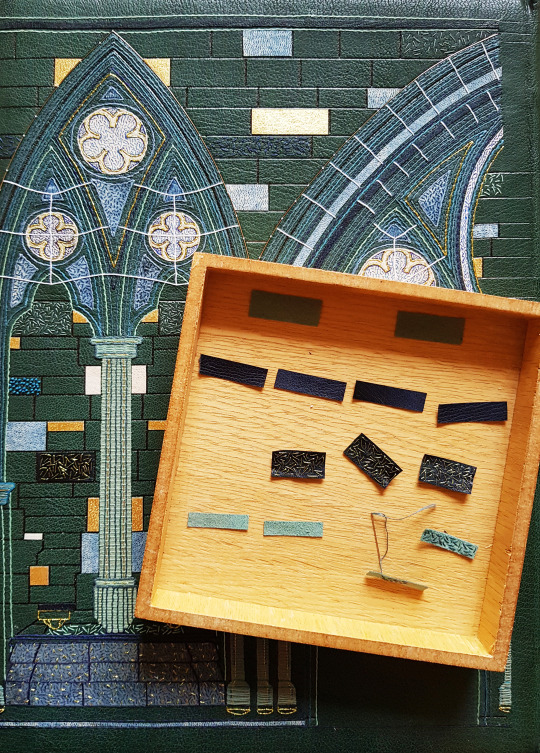

“Music” Miniature Board Commissioned as part of a series on the same theme by Neale Albert, New York, USA. Measuring 3 inches square Made in 2020

This series of boards was inspired by a collection of full size boards which Neale Albert was shown during a trip to George Bayntuns in Bath in 2018. The boards he saw had all been made by members of Designer Bookbinders for a separate project on the theme of Architecture. This project gave Neale the idea for a new project: a series of miniature designer bound boards on the theme of music, three inches (7.62 centimetres) square in size. In early 2019 myself and a number of other binders were asked to participate in this project. Each binder was given total control of the design of their piece (as usual for Neale's commissions) the only common ground between them was to be the size and the musical theme.

Neale started collecting dolls house miniatures in the mid-1980's, which then progressed to commissioning miniature reproductions of his favourite things leading eventually to having entire miniature rooms made for him. But of course miniature rooms need miniature things to go into them, and naturally when Neale's second room project was going to be the library at Cliveden House in the UK he needed miniature books for the shelves! Initially these were blank books purchased at doll house shows until he discovered the world of real miniature books with real type and real illustrations.

I believe that this was the start of Neale's passion for collecting miniature bindings, commissioning bookbinders from around the world to create miniature books for him. Over 250 of Neale's bindings are illustrated in the 2008 publication, “The Neale M. Albert Collection of Miniature Designer Bindings: A Catalogue of an Exhibition Held at the John Rylands Library 4 June – 18 October 2008”, and he has commissioned many more since then too.

When I considered the theme my thoughts naturally turned to cellos as I played the cello up until the age of 20. I made it all the way up to Grade 8 (which seems unbelievable to me now as I can barely remember how to read music anymore!) and was a member of both the orchestra at my secondary school as well as a local music centre. I started learning the cello when I was at primary school - here I am on the far right!

I was also part of a record breaking attempt in 1998 and made it into the local paper (below on the right!). Nearly 4000 young musicians got together at the National Indoor Arena in Birmingham along with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and the conductor Sir Simon Rattle to perform Sir Malcolm Arnold’s Suite No.2, along with school children from all over the country - we successfully broke the previous record of 2212 musicians!

Sadly leaving home to go to university was the end of my cello playing as I decided I didn't want to take such a large instrument away with me. It sat in the cupboard at my parents house for many years however I am pleased to say that it has finally gone to a new owner and is being played again.

As luck would have it a neighbour of mine is a luthier, based in Somerset and specialising in cellos. Kai-Thomas Roth was born in Germany. From the age of eight he knew he wanted to become a violinmaker and made his first instrument at the age of thirteen. After training as a cabinetmaker in Switzerland he came to England to study at the Newark School of Violin Making. Following work experience in the trade he established with his wife Caroline Crowley their business as makers of fine instruments of the violin family in 1990.

Below: Head of Baroque cello, No 103, after Guadagnini (Photo Credit: Kai-Thomas Roth Instgram account @kaithomasrothcellos)

Specialising exclusively in making bowed stringed instruments all experience and expertise gained since 1986 are concentrated on the manufacture of these intricate complex artefacts. For that reason Kai-Thomas neither has a shop nor employees and he does not deal in old instruments or undertake repairs. This puts him amongst the few makers who immerse themselves completely in creating instruments but amazingly he's never played the instrument he so lovingly creates!

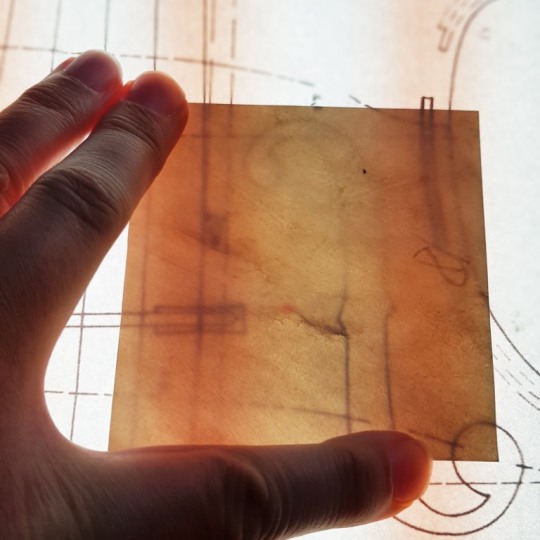

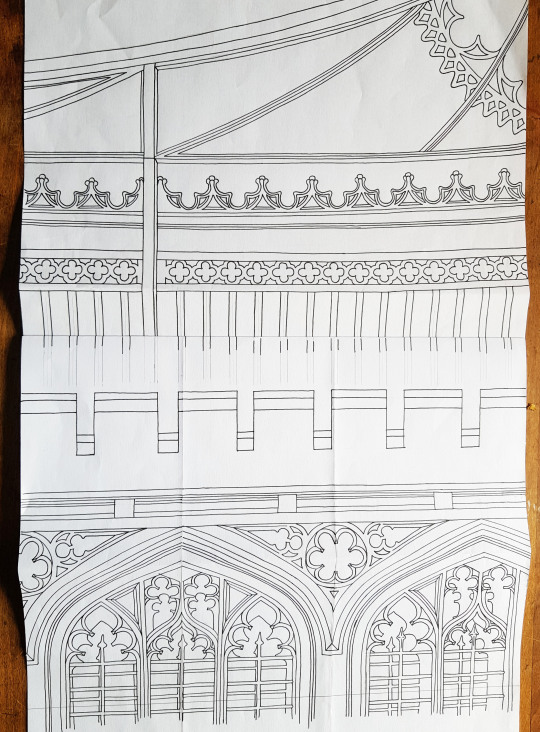

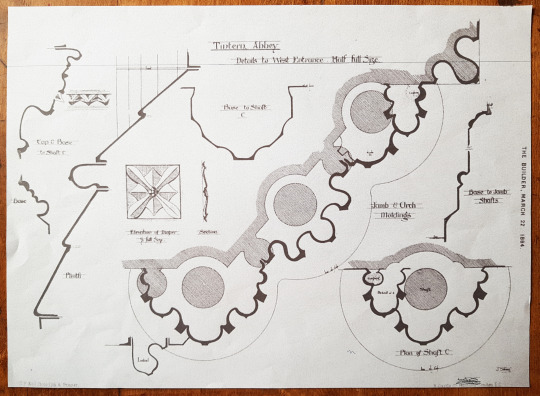

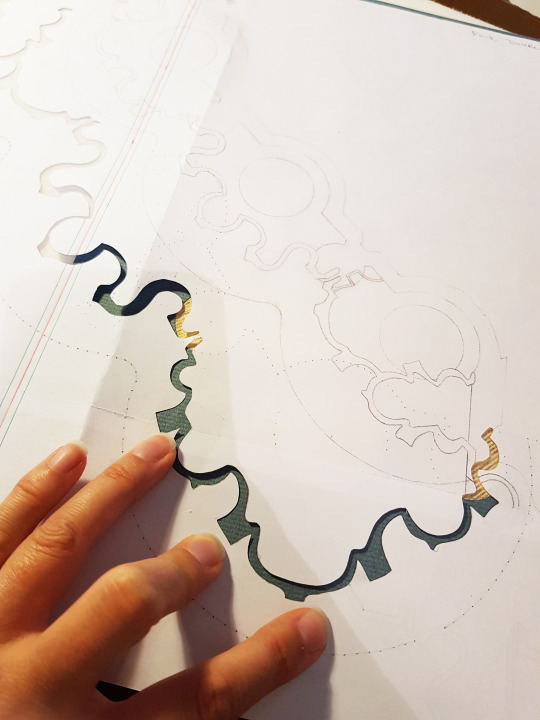

I approached Kai to ask whether he had any technical drawings of cellos that I might borrow to base the design of my board on. What he lent me was a drawing of a “Violoncello Piccolo” made by Johann Christian Hoffmann in Leipzig in 1732. This instrument belongs to the Museum of Musical Instruments of Leipzig University and the maker was in Leipzig at the same time as Johann Sebastian Bach. This violoncello is a small cello that would be played braced against the shoulder rather than between the legs. This instrument is also a five-string version of the instrument, standard cellos have just four strings.

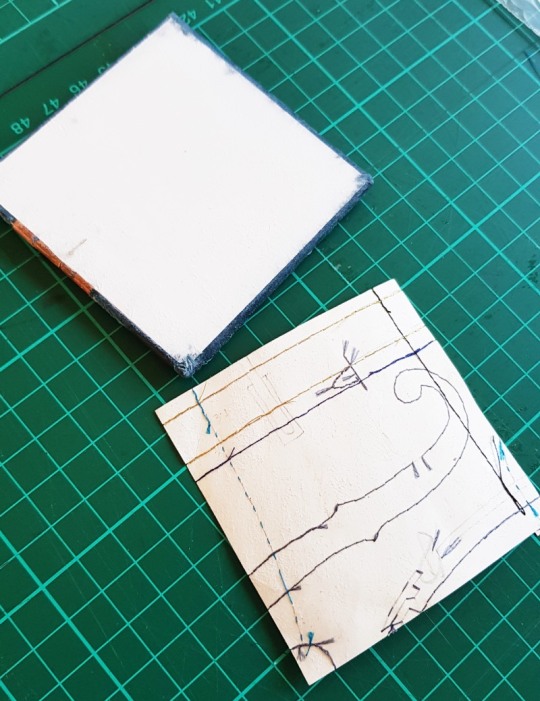

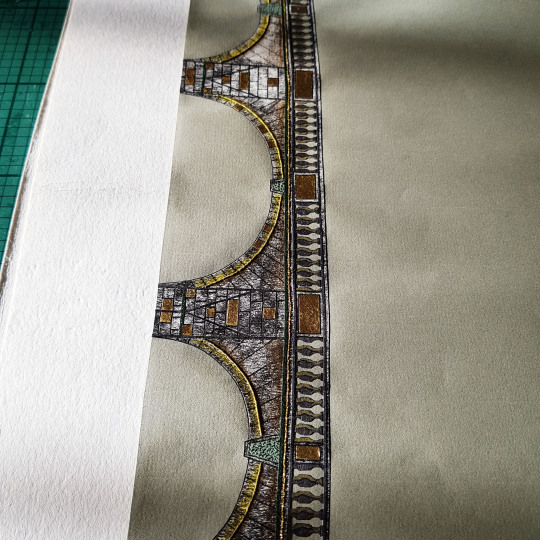

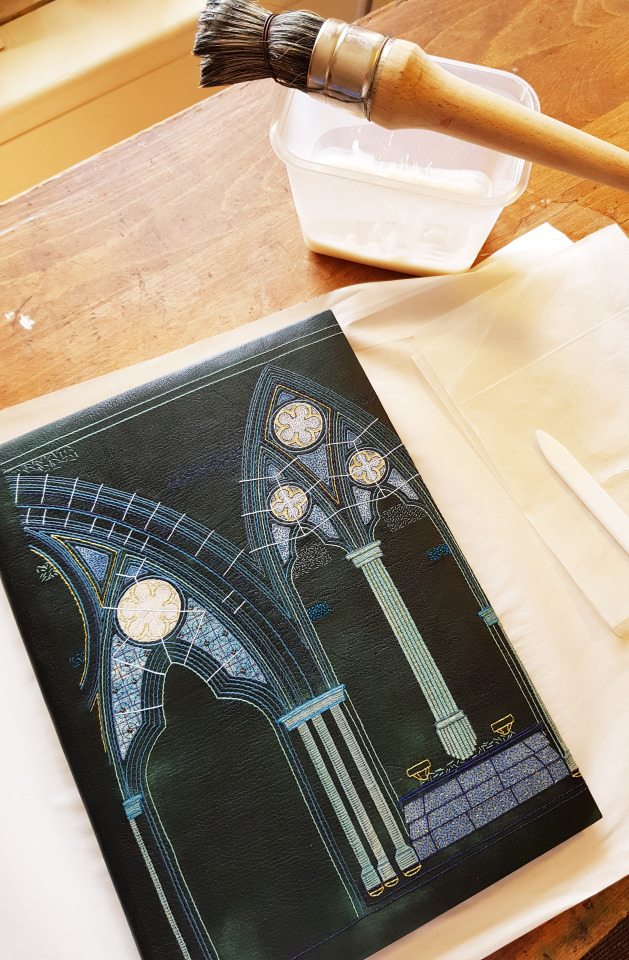

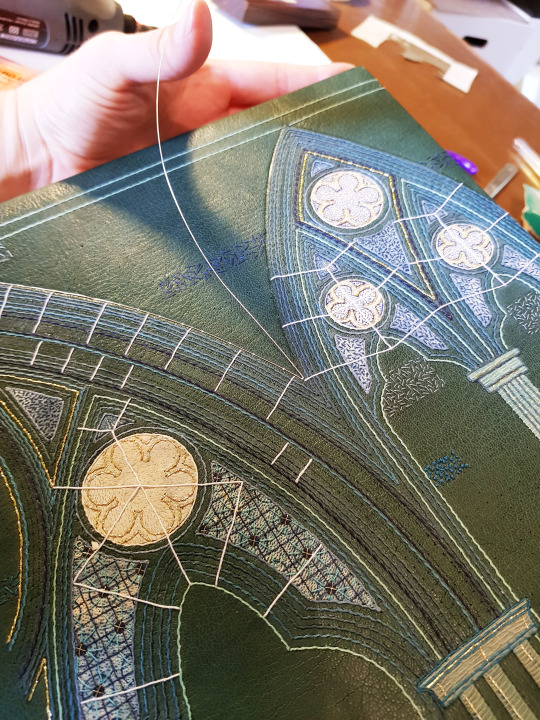

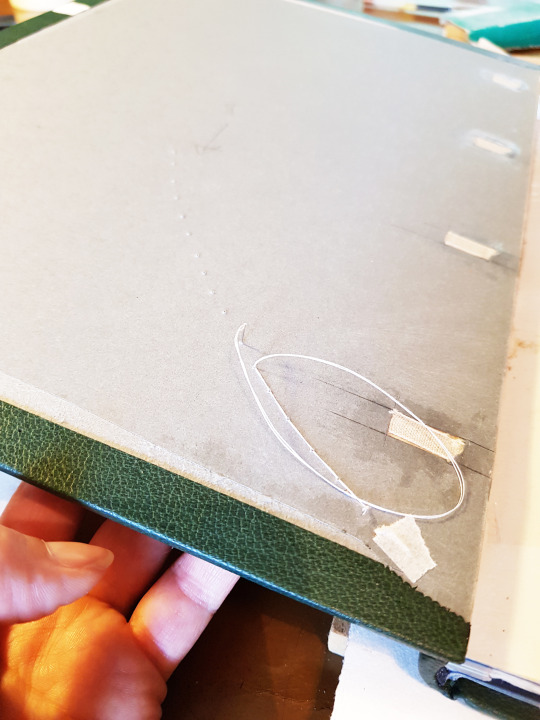

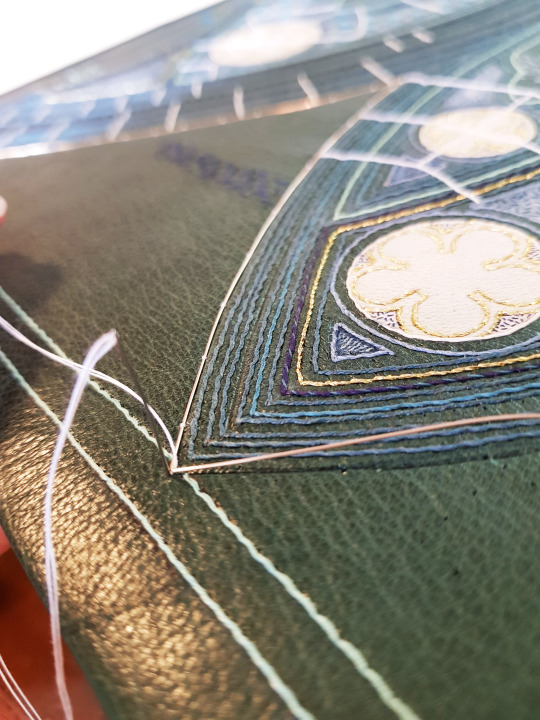

The inner board was made up as I would make up the board for a binding. Two 1mm think squares of Gemini board were glued together, with a piece of kraft paper glued on the inner side of the board and two layers of 145gsm water colour paper to the outside. Once dry the outside face of the board was bevelled using sandpaper.

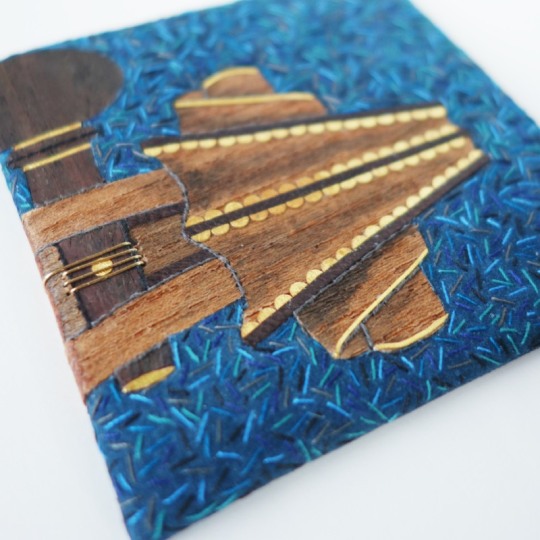

The front of the board is covered in “Colvert” coloured bull skin from the Remy Carriat Tannerie in France, this was edge pared for the turn-ins using my Brockman paring machine and then further pared with a rounded scalpel blade. The bull skin is very stretchy and difficult to pare with a conventional paring knife so I have found through experimenting that I get the best result using a scalpel with a size 23 Swan Morton blade in it.

I traced the scroll section of the cello, including the top peg, onto some paper and transferred this onto the back of the leather I chose to use for the board. I then embroidered a series of individual short lines in a variety of colours of cotton thread to break up the uniform blue of the leather. These stitches were done around the outline of where the scroll was going to sit on the board.

The leather was then pasted to the board, turned in and left to dry. I then cut out the outline of the cello scroll (within the line of stitches) and peeled this away to leave a void. I used two varieties of veneer (Rosewood and Elm), which I backed onto card to give extra thickness and strength, cutting them out very carefully with a sharp scalpel so that they exactly matched the void that they needed to fill.

They were glued in place using PVA glue and held with small clips whilst the glue dried to ensure that they dried flat. Where the veneer met the edge of the board I bevelled the veneer to match the profile of the leather as it thinned towards the edges.

I forgot to take too many photos of how I built up the detail on the veneered sections of the board (I was enjoying this part too much and forgot!), but I drilled small holes right through the board using a fine drill bit in my Dremel and added outlines using thread sewn through these holes. I also added a thin wash of acrylic paint to some areas of the veneer to add an appearance of shading and depth to the surface, plus I also included some detail in gold leaf to jolly up the design!

Finally, I used thin gold wire that was also passed through more small holes drilled in the board to depict the cello string wound round the topmost peg. The wire was passed through the board and embedded into the reverse before being covered with the infill on the back of the board.

Once the back of the board had been infilled and built up it was time to work on the design for the back of the board. I cut a small piece of vellum to 3 inches square and traced another part of the cello technical drawing onto the reverse of it using a light box. This section included part of the F hole and the bridge that supports the strings.

I was then able to use these lines as a guide for embroidering the design using the same colours of thread as used on the front of the board.

I also used some gold leaf and small elements of the “Colvert” bull skin to match what I had used on the front of the board.

The back of the board was built up with a couple of layers of Zerkall paper and sanded flat. Once the vellum was complete I stuck it down to the back of the board and left it to dry, making sure I rubbed it down all over to ensure it stuck down properly.

And so we had a completed board! All that was left to do was to add my signature and a small number annotation to the vellum back of the board then it was photographed and posted over to join the other boards in New York. This was a very pleasurable little project to work in in amongst other commissions and I was pleased to reminisce back to my more musical days!

#bookbinding#bookbindingcommission#workofabookbinder#musician#cellist#cellodesign#luthier#leatherbinding#vellumbinding#goldleaf#embroideredbinding#cellomaker#bullskinleather#technicaldrawing#miniatureboard#miniaturebinding#leatherparing#embroiderythreads#celloscroll#cellopegs#cellostrings

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wigs for “Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk”

Today (Thursday 27th August 2020) the current exhibition, “Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk”, reopens at the Victoria and Albert Museum after a period of closure due to the Coronavirus pandemic.

“This exhibition will present the kimono as a dynamic and constantly evolving icon of fashion, revealing the sartorial, aesthetic and social significance of the garment from the 1660s to the present day, both in Japan and the rest of the world.”

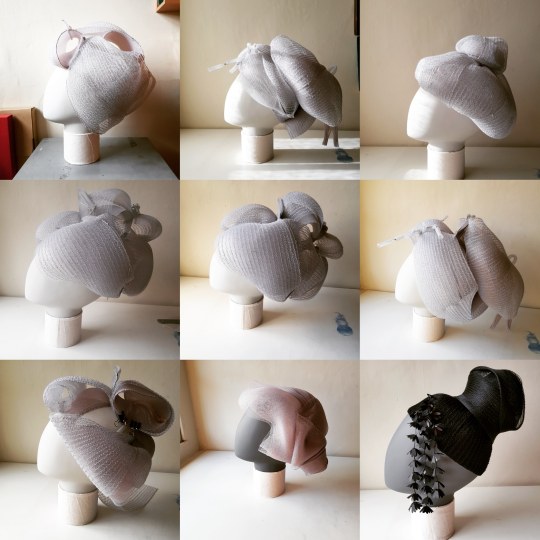

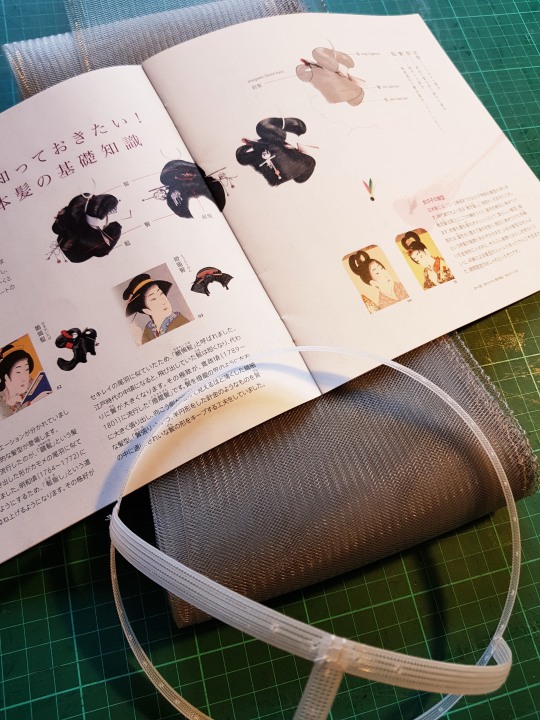

Earlier this year I completed a project for this exhibition, making eleven “wigs” for the fibreglass mannequin heads in hairstyles to represent different periods in Japanese history.

(Image credit: Rachael Lee, Textile Conservation Display Specialist in the Textile Conservation Department at the V&A)

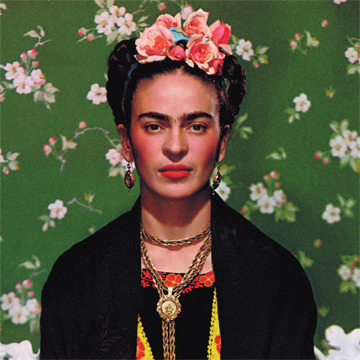

The wigs for this exhibition were intended to be abstract and an impression of the silhouette, rather than incredibly detailed, so as not to distract too much from the costume displayed on the mannequins. When wigs are requested for mannequins, they are often made in house at the museum by the Textiles Conservation and Mounting Department, but due to restrictions on time they were outsourced on this occasion. I was involved in a similar project for another V&A exhibition back in 2018, “Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up”, which involved making three headdresses constructed from paper flowers. One of my previous blog posts details the making of these.

The wigs for the Kimonos exhibition were to be made from milliners crinoline, or “crin” for short, which in its nature is really springy and easy to make into voluminous shapes. Crin is an extremely versatile fabric that can be used for millinery, craft and haberdashery as well as fashion and dressmaking. The intention was to form shapes by manipulating it and stitching it together, then attaching these pieces to a Rigiline frame which would sit on the head of the mannequins. Rigilene is a type of boning made of woven nylon rods and can be stitched directly to fabric, without a casing.

The concept of these crin and rigilene wigs was not new, in 2011 an article was published in the V&A’s Conservation journal entitled, “Keep Your Hair On - The development of conservation friendly wigs”:

“One of the challenges we regularly encounter when displaying head wear is how to achieve a good fit with proper support when headdresses are designed to be worn upon elaborate hair styles. The solution to this quandary would appear easy enough; give heads hair. This seemingly straight forward answer was not as easy to apply as one might think largely due to exhibition designers and curators desire to display objects on non-realistic, abstract mannequin forms. This current trend is considered least distracting to the audience’s appreciation of the costume itself.”

My contact at the museum was Rachael Lee, a Textile Conservation Display Specialist in the Textile Conservation Department, who had been working for many months displaying numerous kimonos for the exhibition. She and some of her colleagues had already worked on a couple of protoypes of the wigs that were sent to me to get an idea of the forms they wanted. I was however told that I was to have creative control over the wigs and to have fun with them!

For the eleven wigs that they wanted I was supplied with reference images to work from.

The wigs were to be built on to Rigilene frames. I first measured the circumference of the fibreglass head at approximately the point where I wanted the hairline of the wigs to sit. I left a bit of slack knowing that the frame would get packed out a bit when the crinoline layers were attached. I cut a strip of Rigilene that was overlong so that it could be overlapped and joined together to form a circle, I drilled a series of small holes through the overlapped pieces and then stitched through them to hold the loop together. A second piece of Rigilene was then cut to span the top of the head, and it was joined to the first ring, slightly off centre, in same way using thread. Finally, a shorter piece was cut to tether the outer ring and the central bar together at the back.

As the Rigilene was quite springy, initially I temporarily joined the overlapped pieces using a dab of superglue and held them in place with a bulldog clip whilst it set. This then helped as the two pieces of Rigilene were set in place and held together for me to drill the holes using my Dremel. This process was reproduced a number of times to give me enough frames to experiment with and work from.

As I was working remotely from home, I sent many images of the wigs at various points in their construction to Rachael Lee, who in turn showed them to the curators who gave me feedback during the making process. I had never worked with either Rigilene or crin before so it was a learning curve, manipulating the crin into different shapes and forms to make the 2D images I had into three dimensional forms was a fun challenge!

Further blog posts are to follow in the coming days about the steps I took to create these flamboyant wigs, from the subdued “Gibson Girl” through to the elaborate “Courtesan” with some more modern “Memoirs of a Geisha” characters thrown in I feel I have learnt a lot about Japanese hairstyles along the way!

#kimonos#kyototocatwalk#v&a#victoriaandalbertmuseum#courtesan#geisha#crinoline#rigilene#samurai#kimonofashion#hairstyles#wigs#japanesehairstyles#workofabookbinder

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

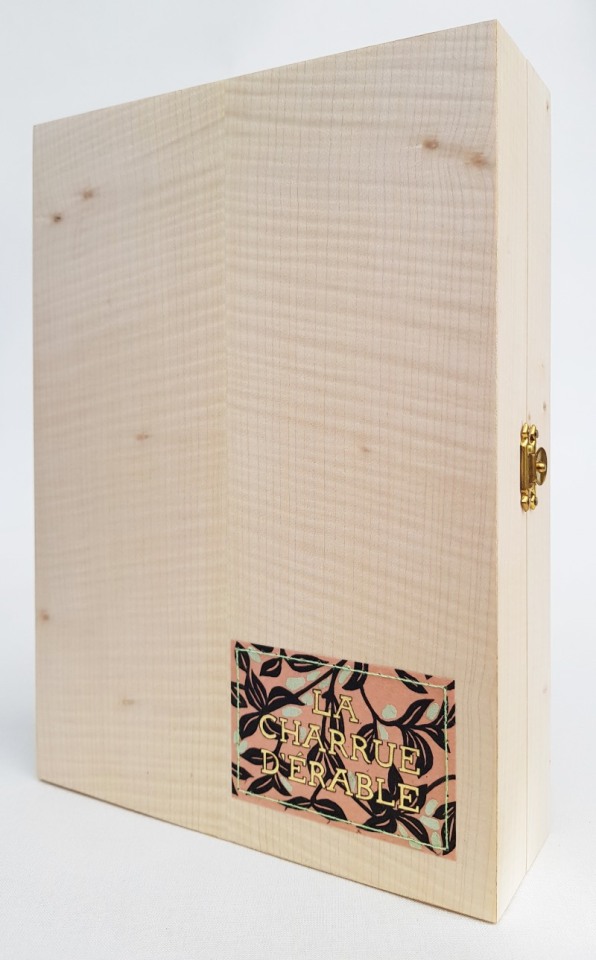

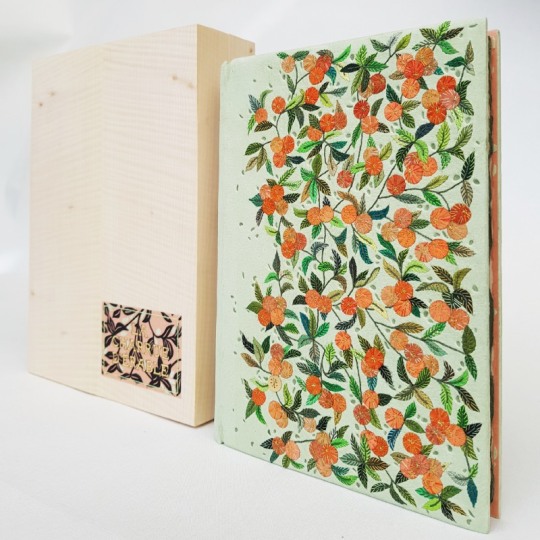

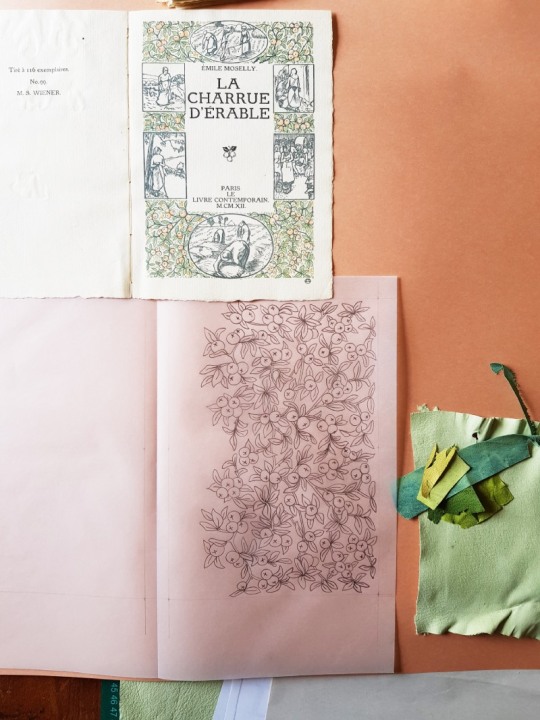

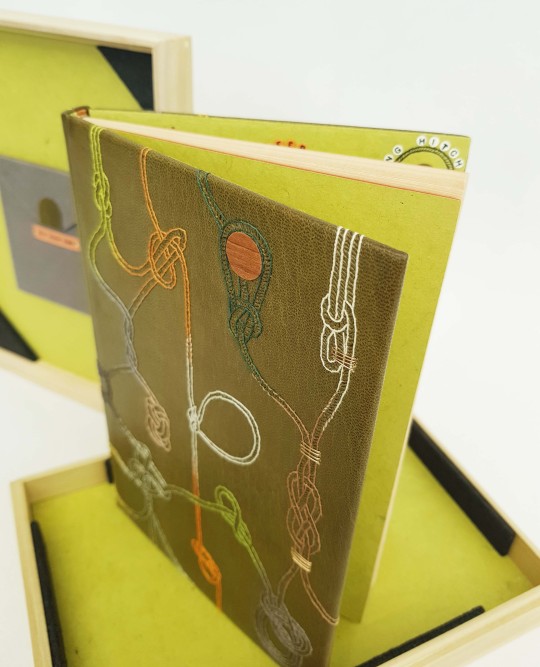

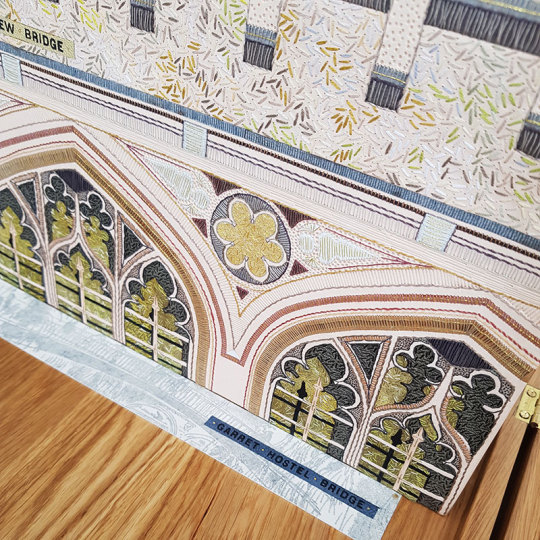

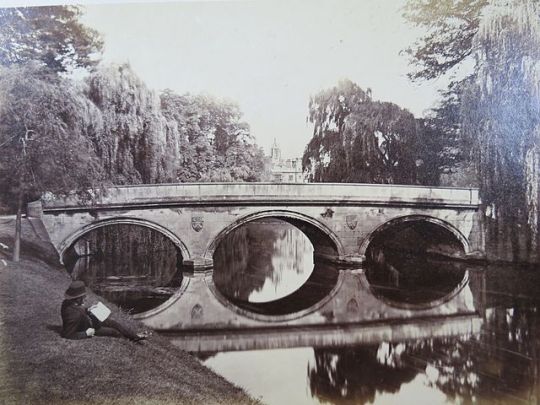

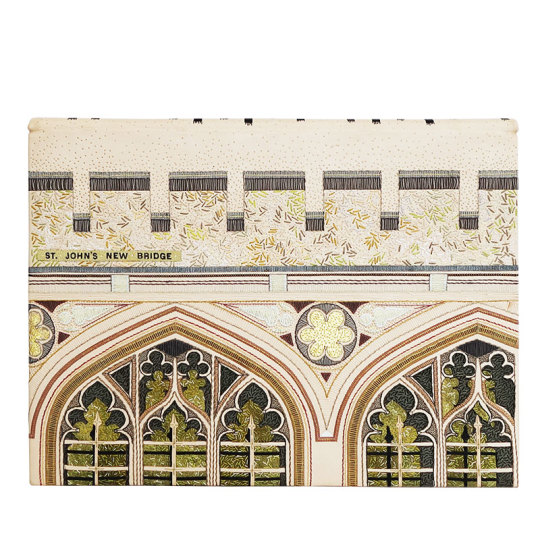

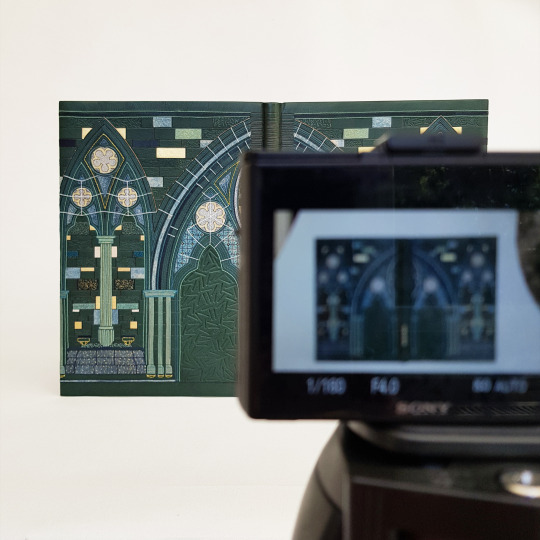

“La Charrue D'Érable” (The Maplewood Plough) Part Five: Completed Binding

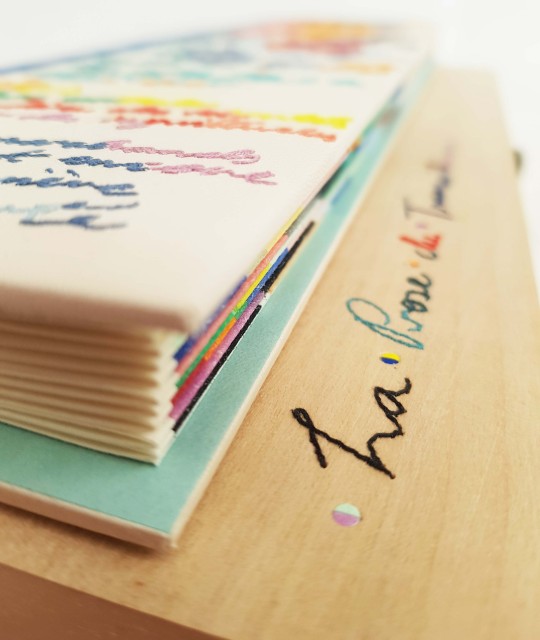

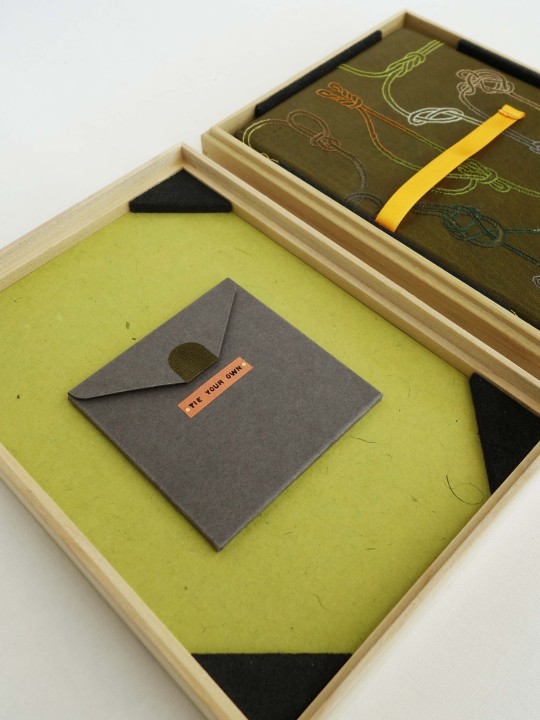

And so the binding was complete! I used a spare piece of the endpapers to create a title for the box. The words were pierced out using a scalpel and backed with gold leaf. The title was then sewn to the lid of the box through small holes drilled around the outside of the label.

I knew early on that wanted the container to be made from Maple wood to tie in with the book title and I was pleased to be able to source some. The inside of the box was lined with felt, with a ribbon lifter attached to help to get the book out of the box.

THE COMPLETED BOX

THE BOOK IN THE OPEN BOX

THE BOOK ON THE OPEN BOX

THE BOOK NEXT TO THE BOX

THE EDGE DECORATION

THE FULL COVER

THE PASTE-DOWNS

BACK COVER DETAIL

FRONT COVER DETAIL

THE ENDPAPERS

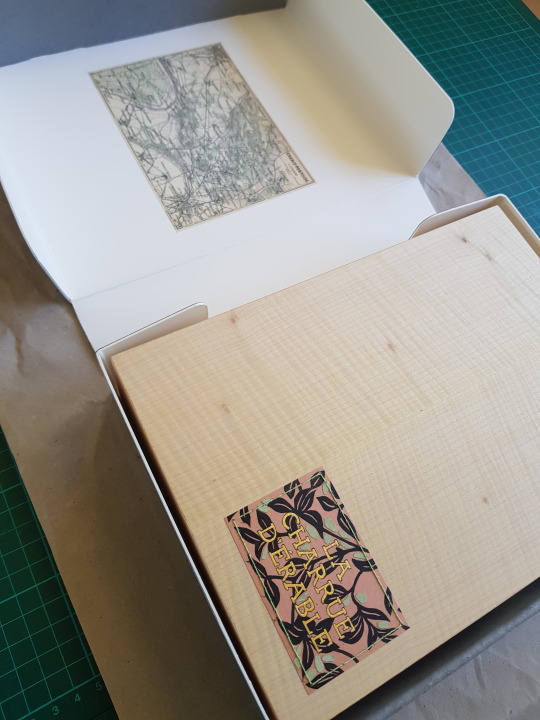

I was finally able to order the outer conservation box from The Bodleian Library a few weeks ago.

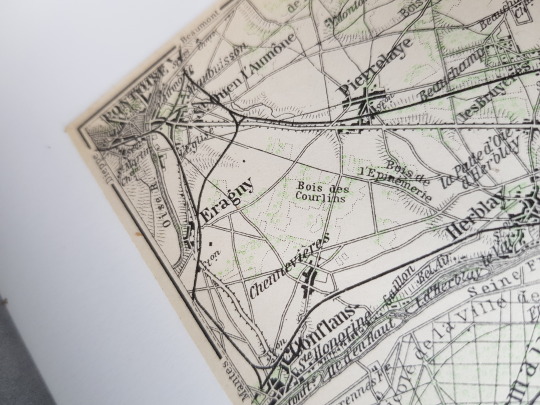

As well as adding a title to the spine, I glued into the inner lid of the box a map dating from 1910, showing the area of "St. Denis-Pontoise" in France, including the town of "Eragny".

The press was named after the Pissarro family's home village in Normandy, I will have to try and visit it someday!

#bookstagram#bookshelf#reading#booklover#bibliophile#bookbinding#craft#leather#inspiredbynature#tooling#designbinding#artbookbinding#reliuredart#reliure#finebinding#leatherbinding#firstedition#hannahbrown#contemporaryembroidery#thread#bookcollecting#erangy#erangypress#pissarro#lucienpissarro#camillepissaro

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

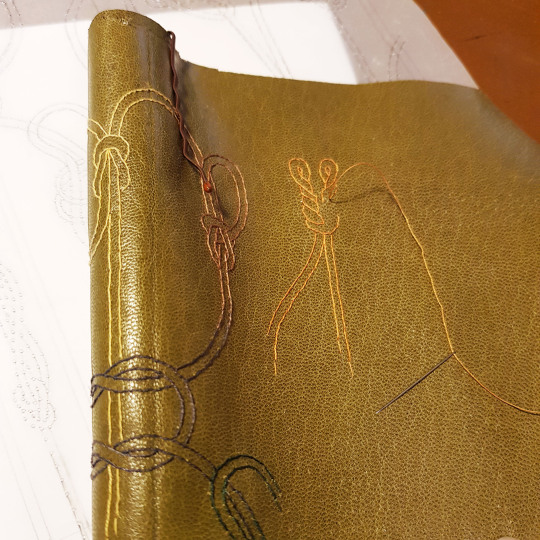

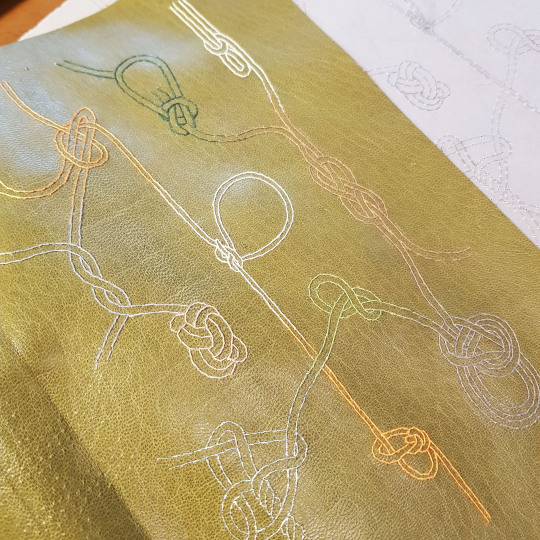

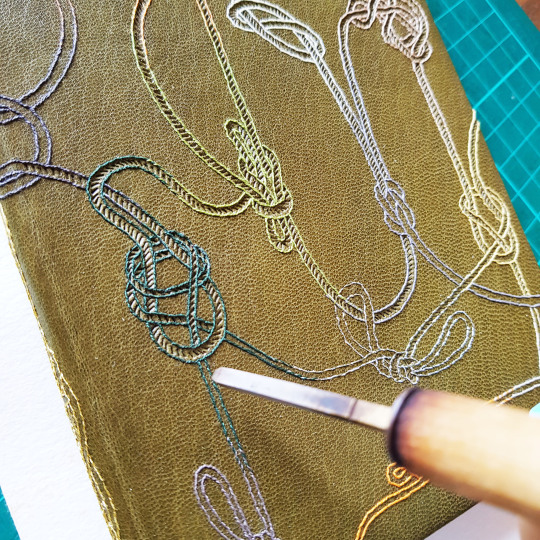

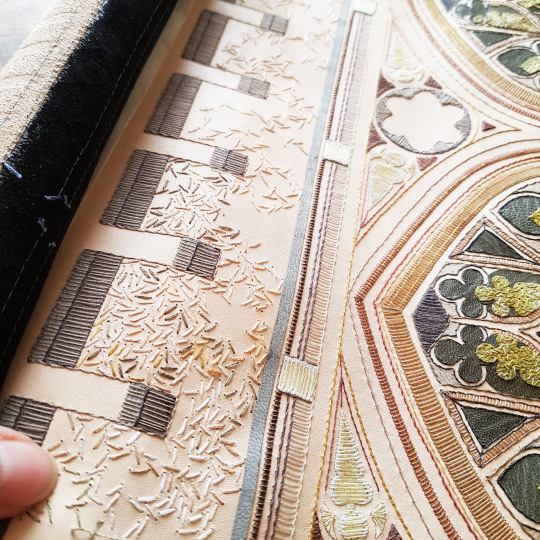

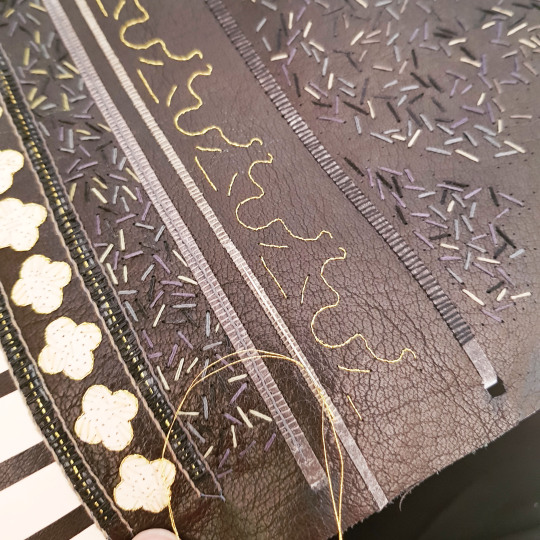

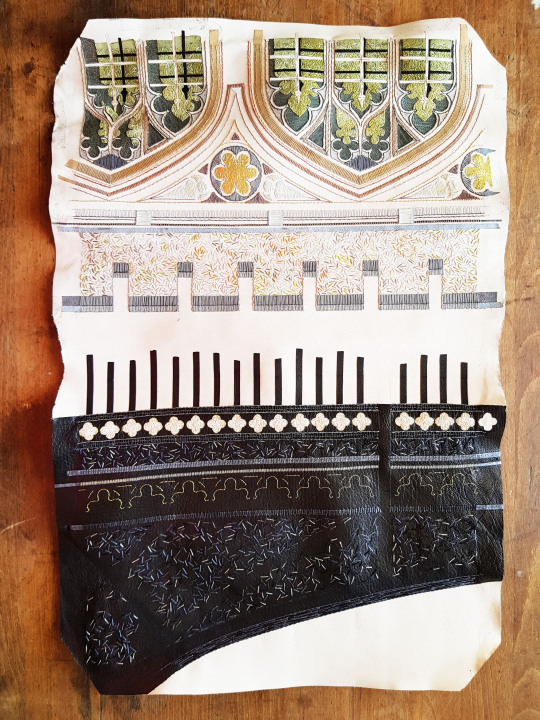

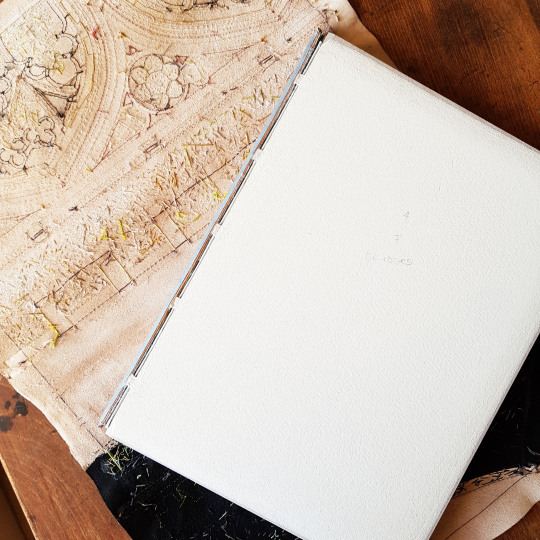

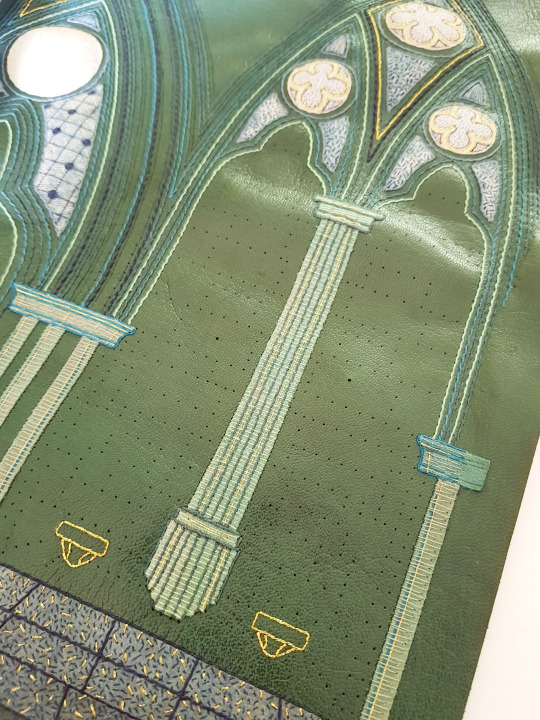

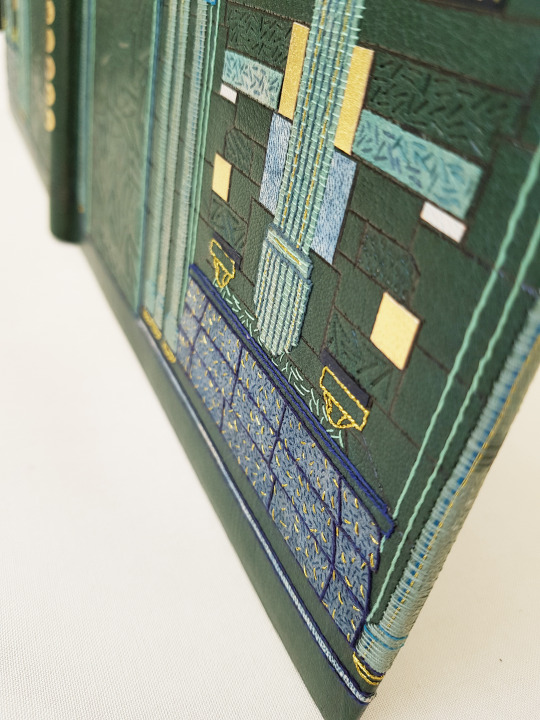

“La Charrue D'Érable” (The Maplewood Plough) Part Four: Embroidery and Covering

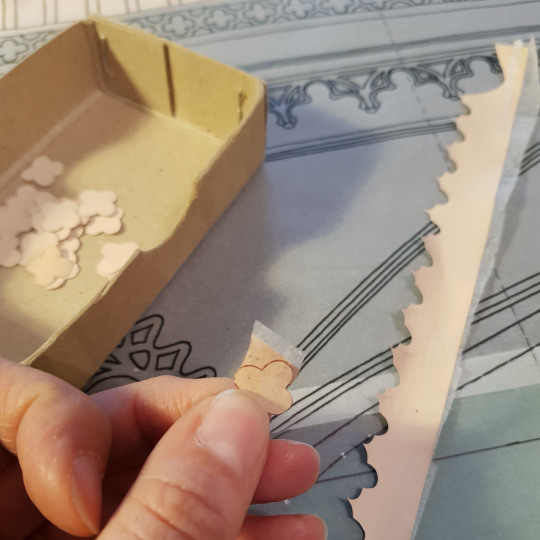

Finally the time had come for me to do the bit that I like the most - decorating the covering leather! The first step in the process was to cut out all of the leather onlays I needed to complete the design, including lots of lots of little leaves. On a couple of occasions I brushed past these loose leaves sitting on one of my benches and dislodged a few and it was a rather frustrating game trying to find their correct positions again!

When it came to the apples, I cut out a multitude of discs in different tones of leather and tried to spread the colours out as evenly as possible over the front cover.

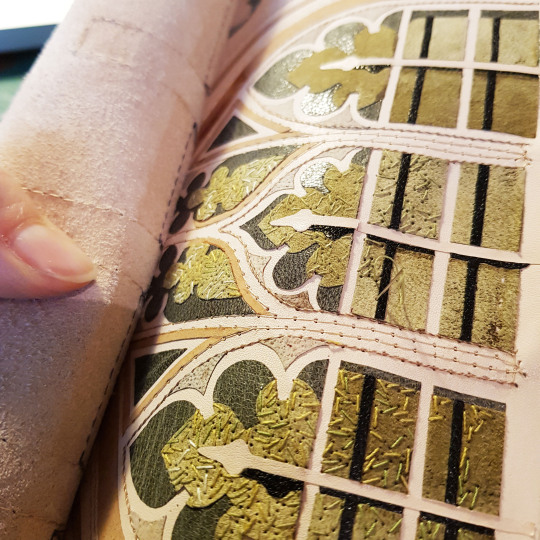

Once all of the onlays were down, I went through my box of threads and pulled out a selection of greens, reds and oranges with which to start sewing the detail onto the cover.

Firstly I concentrated on sewing all of the ‘branches’ using a dark green thread. This also helped to secure each of the leaves onto the leather. Each leaf in turn was then further embroidered with little stitches all the way up in a contrasting green to the colour of the onlay. As the leaves on the front and back covers were mirror images of each other, I made sure to sew the corresponding leaves in the same coloured thread.

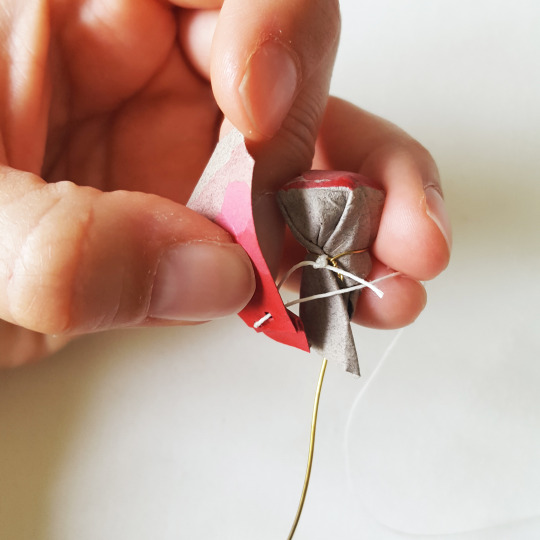

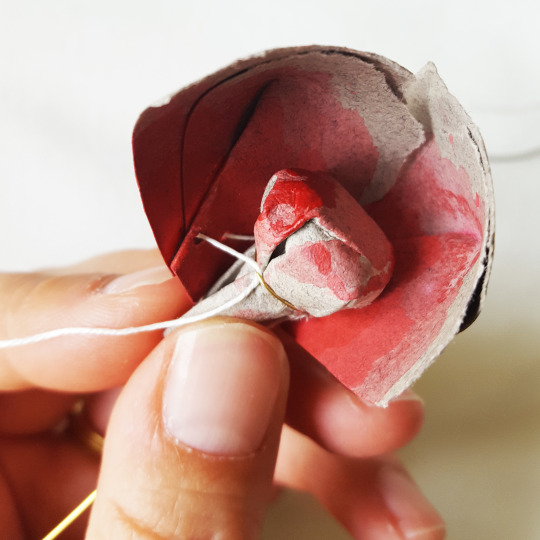

The apple blossom was attached to the leather using a double criss-cross stitch to look like the stamens of the flowers. I pricked the holes first with a needle pricker as the vellum inlays were tough to push a needle through.

Onto the end of each of the criss-cross stitched (eight in total for each flower) I tied a small French knot. These were done in a variety of different coloured threads to add variety.

The apples on the front cover were also embellished with a variety of coloured threads, enhancing the colour whilst also securing the onlays down.

The back of the leather looked like this once the embroidery was complete - a random scattering of coloured threads!

So, the time had come to cover the book, always a daunting task after spending so much time embroidering the leather beforehand. I laid a few layers of newsprint down onto my bench and got together all the tools I needed for the process: sharp scissors, teflon folder, scalpel, fine metal tools for forming the head caps and some cord, also for forming the head caps.

The front of the leather was spritzed with some water to prevent marks from forming on the front of the leather once it dried. The back was pasted out three times using flour paste, with time left in between each application to allow for it to absorb into the leather.

The covering of the binding requires all the hands and nerves I have so I often don’t get many photos of this part of the process! The leather went down well and the book was left to dry under weights between blotting paper for 24 hours, with the blotters changed regularly. The following day, I dampened the joints with a water pen and carefully opened up the boards. The leather joints were stuck down into position with PVA whilst both of the book boards were open.

I bought some 18 carat yellow gold sheet in order to add one gold apple to the front cover. This was pierced into shape using a jeweller’s piercing saw and holes drilled through it. One of the criss-crosses was sewn with metallic gold thread, the other had gold wire passed across it to physically attach the gold apple to the book board through small holes that had been drilled using my Dremel..

Small channels were cut out of the reverse of the board and the ends of the gold wire were bent into these to permanently fix the gold apple in its place. The insides of both the front and back boards were then infilled and sanded. The first layer was some watercolour paper, which was the same thickness as the turn-ins and the leather joint. The second layer was a piece or Zerkall, cut a few millimetres smaller than the size of the boards. This was then sanded completely flush to get rid of any lumps and bumps.

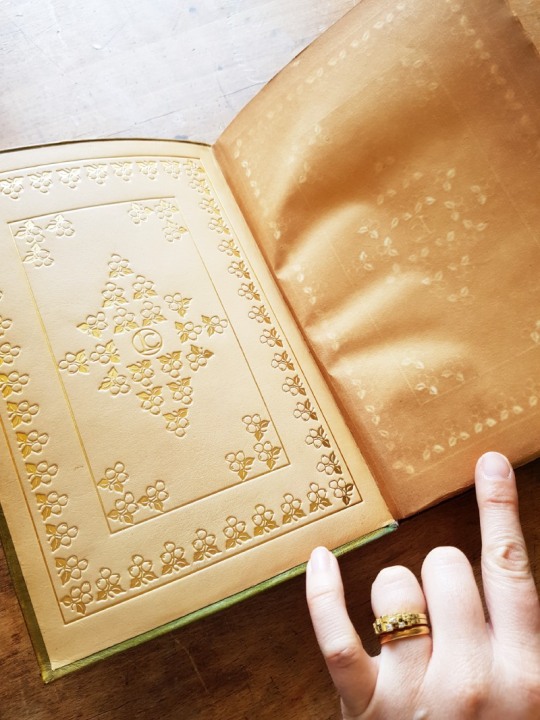

It was then time to stick the paper doublure down to the front and back boards. All of the pierced shapes had been filled with gold leaf backed onto Japanese tissue.

Once stuck down, I wanted to add extra detail to the endpapers and doublures. For the apples inside the front board, I cut out tiny criss-crosses from black paper.

These were then stuck down onto the gold using PVA glue.

For the blossom inside the back board, I used black acrylic paint on the end of a needle pricker and applied paint to each of the flower centres.

Finally, I wanted to add a little of the cover leather to the endpapers and doublures. I cut out small shapes from thinly pared cover leather and stuck them randomly amongst the branches.

The next, and final, blog post in this series shows images of the completed binding and wooden box that was made for the binding.

#bookstagram#bookshelf#reading#booklover#bibliophile#bookbinding#craft#leather#inspiredbynature#tooling#designbinding#artbookbinding#reliuredart#reliure#finebinding#leatherbinding#firstedition#hannahbrown#contemporaryembroidery#thread#bookcollecting#erangy#erangypress#pissarro#lucienpissarro#camillepissaro

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

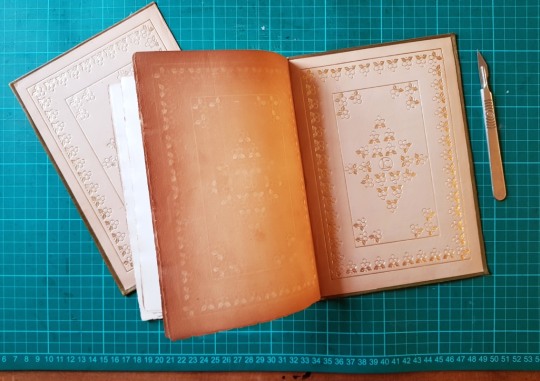

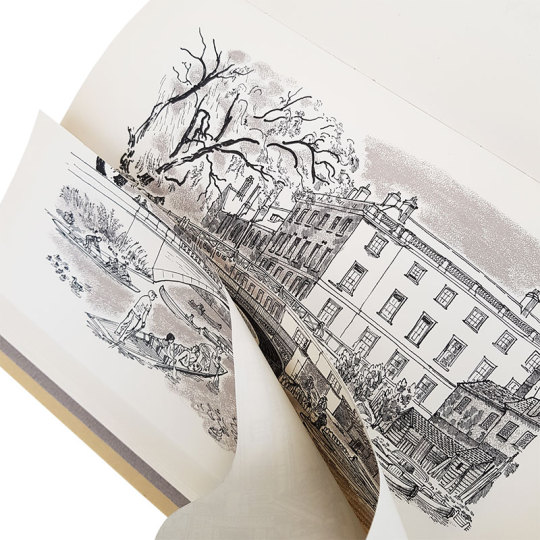

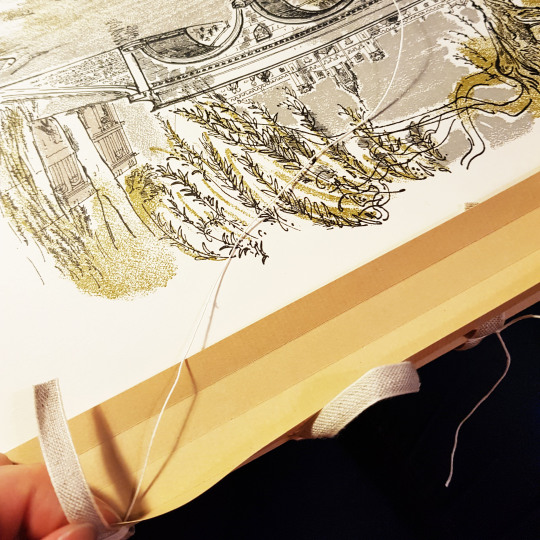

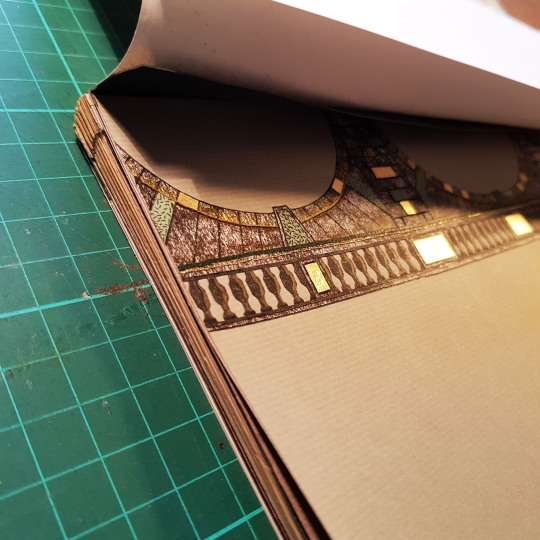

“La Charrue D'Érable” (The Maplewood Plough) Part Three: Forwarding

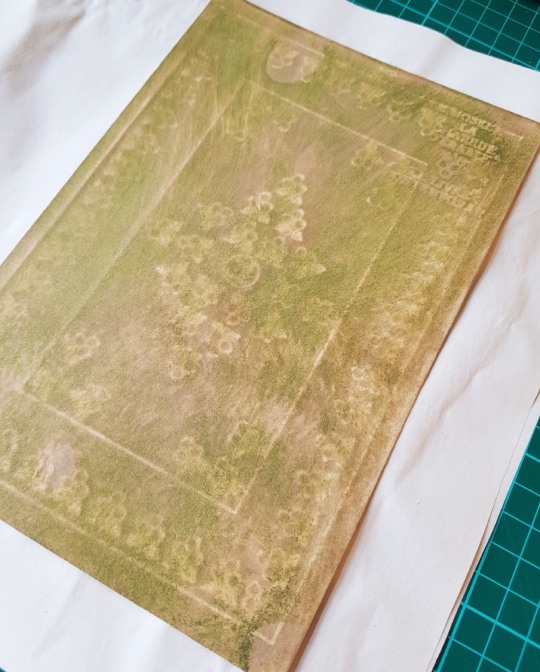

The client wished to retain the gilt calf paste-downs if possible to include them within the new binding. To do so it meant removing them from the existing limp cover so I could mount them to new sheets of paper.

The leather of the limp calf cover had started to degrade, so I removed it by peeling it back carefully from the reverse of the paste-down. I was then able to sand the surface using a fine sandpaper.

Once sanded the paste-downs were mounted to a bi-folded sheet of paper and sewn to the textblock as an additional section on the front and the back. I wrapped a bi-folded strip of paper to this new section as a guard, the other side of which (as visible in the below photograph) was then tipped onto the endpaper section once that had been sewn to the textblock.

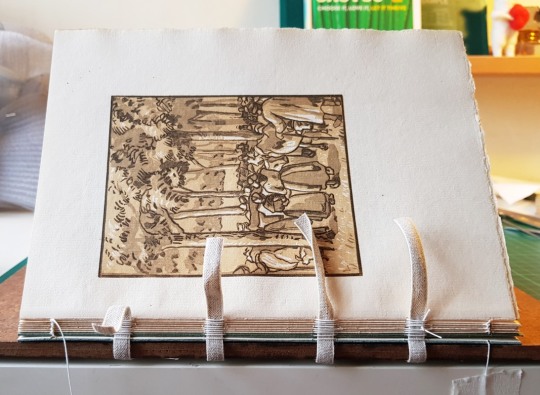

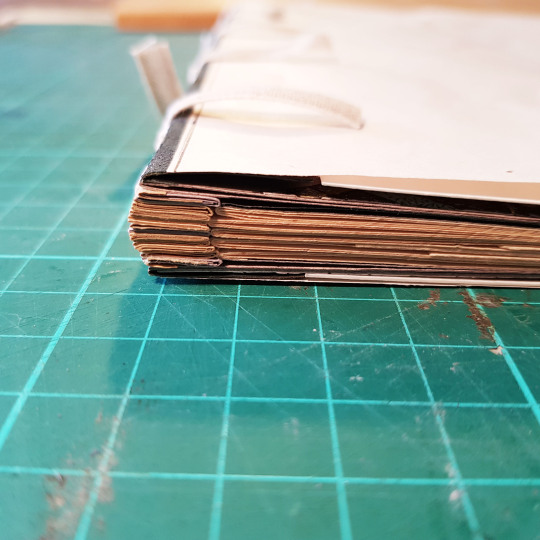

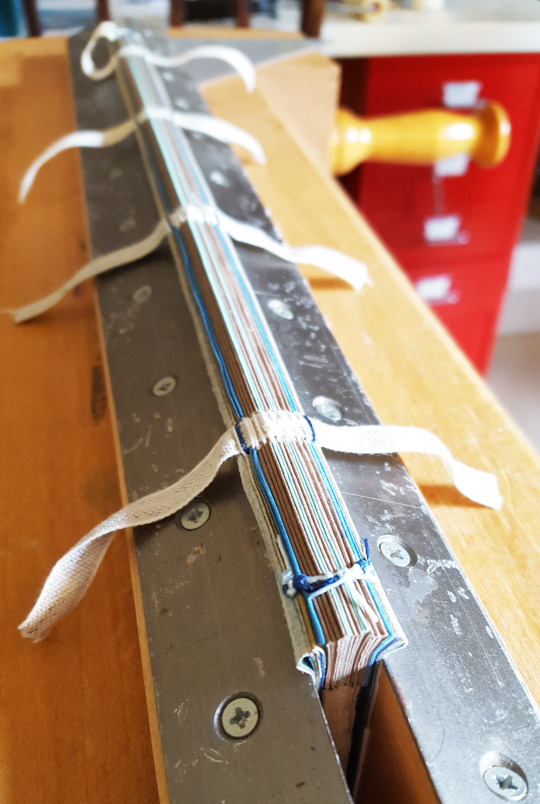

The sections were all then sewn together onto four tapes.

Once all the sections were sewn together, with the endpapers added on at either end, the spine of the book was glued up in-between the tapes with PVA glue and left to dry.

I then rounded and backed the book, and lined the spine attaching a one-on, two-off hollow and then sanded the top edge flush. I wanted to add some edge decoration and did so using watered down acrylic paints. I first applied a thin layer of dark green to match the paper I had used to mount the new paste-downs onto. I further built up the colour by dabbing on small amounts of white, peach and green paints on top to create an abstract pattern in colours to match the binding.

The foredge and bottom edge were left deckled so I did not need to apply edge decoration to them. The next stage was then to sew the endbands. I selected colours that I thought would work well on the binding.

I then created double core endbands using a mixture of these coloured endband threads. The larger core was made from a lamination of leather and a thin strip of vellum. The vellum side was paced pointing towards the top edge of the binding to try and keep a crisp edge where the endband silks wrapped over it. The smaller core was made by stiffening some linen sewing thread with PVA glue and letting it dry out.

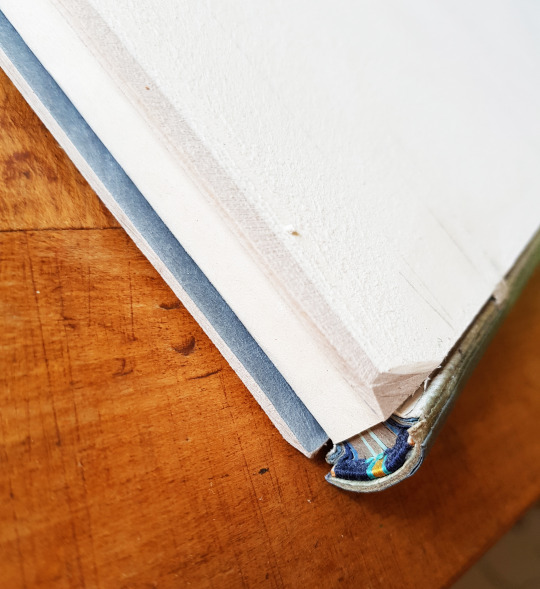

The boards were then laced on and bevelled. The covering leather was pared in preparation for the next stage of the binding process.

The next post details how the leather onlays and embroiderd elements were added to the covering leather to build up the design.

#bookstagram#bookshelf#reading#booklover#bibliophile#bookbinding#craft#leather#inspiredbynature#tooling#designbinding#artbookbinding#reliuredart#reliure#finebinding#leatherbinding#firstedition#hannahbrown#contemporaryembroidery#thread#bookcollecting#erangy#erangypress#pissarro#lucienpissarro#camillepissaro

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

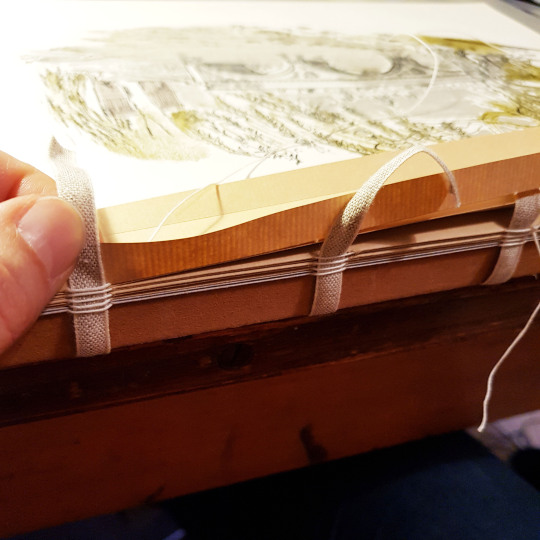

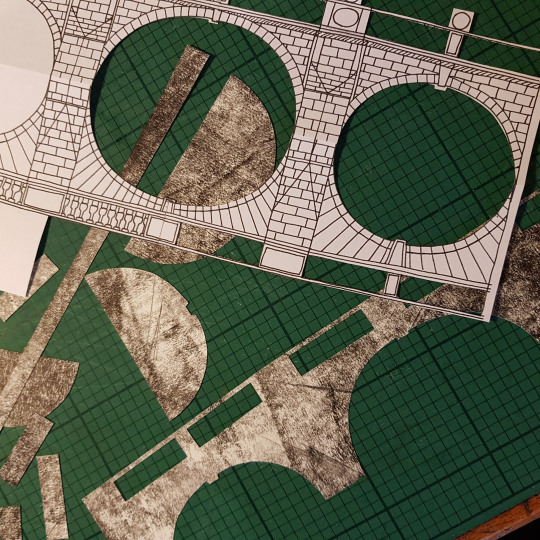

“La Charrue D'Érable” (The Maplewood Plough) Part Two: The Endpapers and Doublures

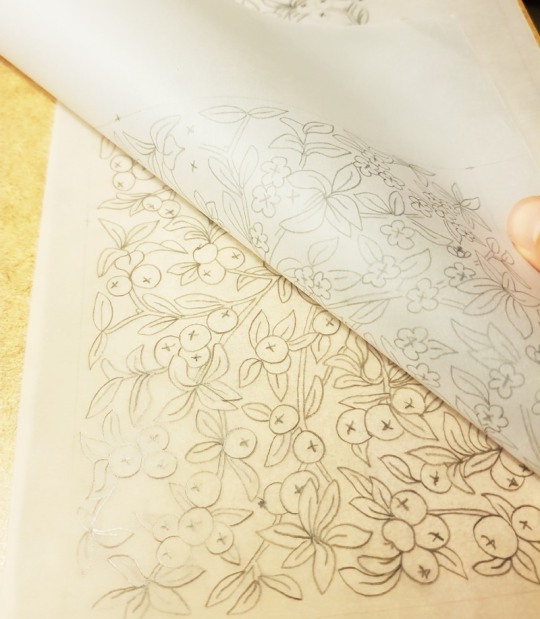

Throughout the book there were numerous wood cut prints so I decided to try out some lino printing to tie in with this. In order to transfer the design onto the lino for cutting I placed a sheet of carbon paper on top of the lino. On top of that I laid a line drawing of the design and then I traced the lines with a biro in order to leave a mark through the carbon paper on the surface of the lino.

I only wanted to print the leaves using the lino plate, so only marked these areas through the carbon paper. It was very clear to see what I needed to cut once I was done marking the lines.

I invested in some rather lovely new “Pfeil” lino cutting tools in a variety of cutting shapes. Each tool is made from chrome vanadium steel with ergonomically shaped hardwood handles – they made slicing the lino a breeze!

The sample board was done in the same manner, just cut on a smaller scale.

The cut lino was inked up with black intaglio ink using a roller.

The apricot Satogami paper was then laid on top of the lino plate and put into a press. Once printed they were pegged up and left to dry for a few days, I did extra copies so I could select the best ones for the final binding.

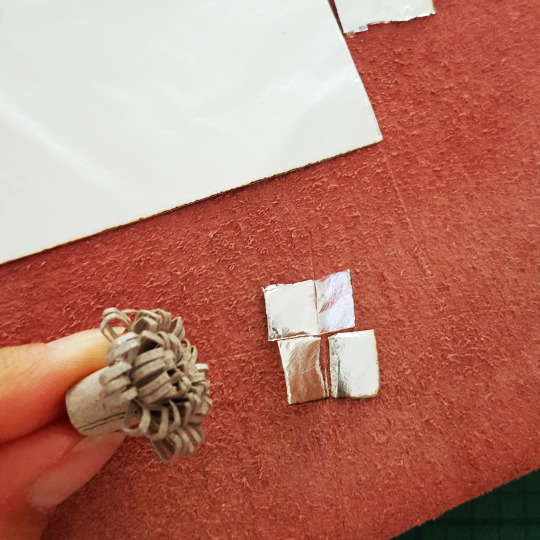

I chose to split the cover design so there were apples on the front and apple blossom on the back of the book. I wanted this difference to carry through onto the endpapers and doublures. To add another level of complexity to the design I decided to make it so that each of the flowers and apples on the endpapers and doublures would have gold leaf behind them to catch the light when the book boards were opened which meant cutting out each shape using a scalpel.

I glued some squares of gold leaf to Japanese paper in preparation using PVA glue and left them to dry.

I flipped both the paper-backed gold leaf and the pierced endpapers over and drew around the shape of the flower and apple clusters that I needed to back onto the reverse side of the gold leaf.

I then made a slightly oversized cut around the pencil outline so that there was enough extra to glue it onto the reverse of the printed paper to span the pierced void.

The next post covers the forwarding of the book!

#bookstagram#bookshelf#reading#booklover#bibliophile#bookbinding#craft#leather#inspiredbynature#tooling#designbinding#artbookbinding#reliuredart#reliure#finebinding#leatherbinding#firstedition#hannahbrown#contemporaryembroidery#thread#bookcollecting#erangy#erangypress#pissarro#lucienpissarro#camillepissaro

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

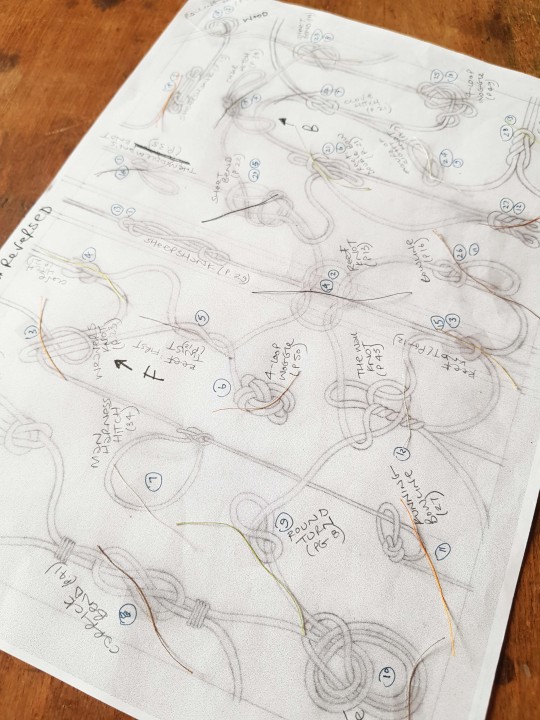

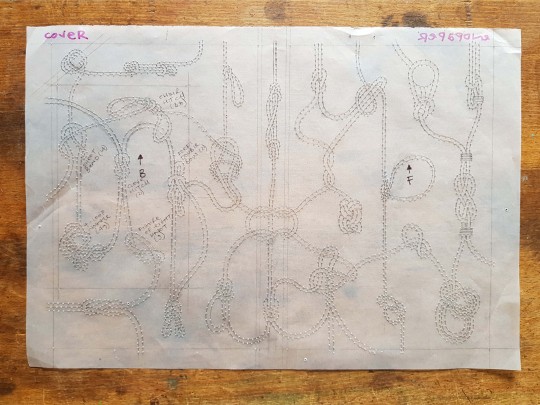

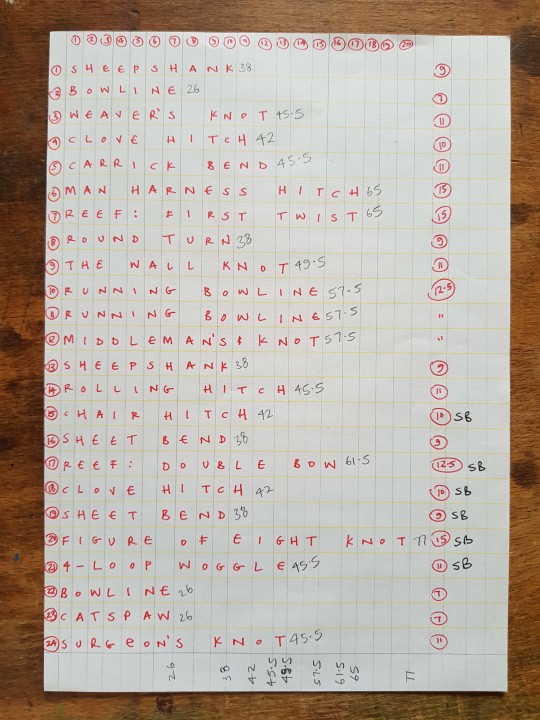

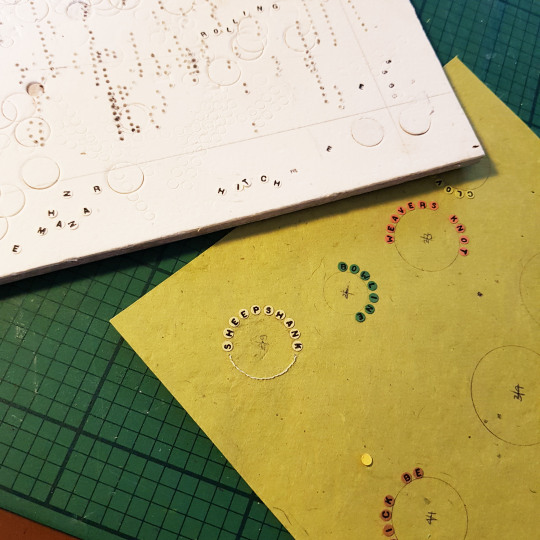

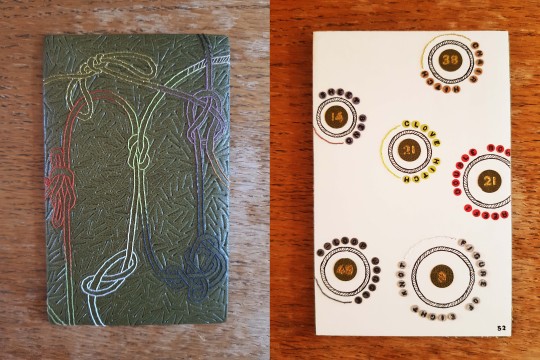

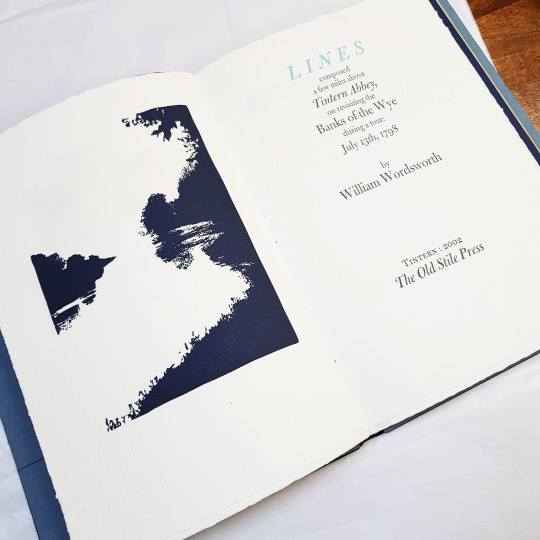

“La Charrue D'Érable” (The Maplewood Plough) Part One: Design

I was shocked to look back at my last blog post to see that it was back in August of 2019, nearly one whole year ago, where did all that time go? I have found it is all too easy to get out of the habit of writing, unless I do so as soon as I have finished a binding or project it seems like a real effort to look back retrospectively and write a post. I have five outstanding things to write about, all of which with photos to edit which seems a bit of a mammoth task!

So, to kick start my blog again I am starting with a binding that I have literally just shipped off to France to a client, I hope it reaches him safely and is well received. In fact the binding itself was finished a couple of months ago but due to the global pandemic I was unable to order an outer conservation box for it, I get these from the University of Oxford, so the binding sat safely in its wooden container in my plan chest until I was able to place an order for a box of the correct size.

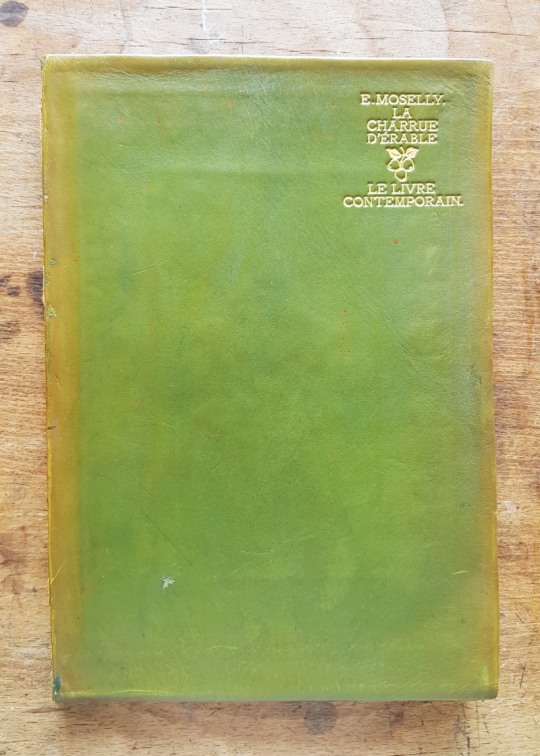

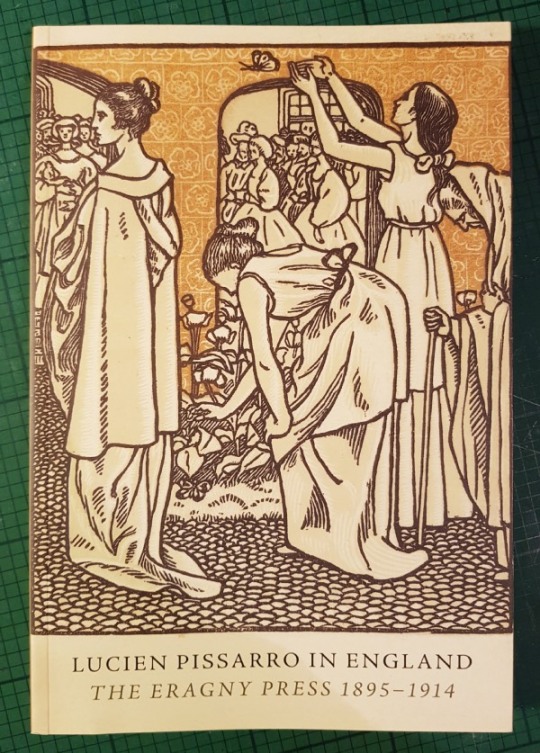

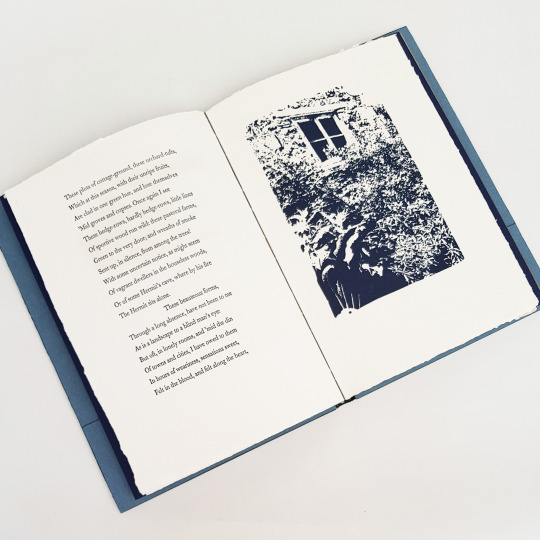

The binding is a copy of, “La Charrue D’Érable” (The Maplewood Plough), one of 116 copies printed in 1912 at the Eragny Press in France. The Eragny Press was founded by Lucien Pissarro (1863-1944), the son of the Impressionist, pointillist painter Camille Pissarro. The press was named after the Pissarro family’s home village in Normandy. The Eragny Press specialised in small hand-made books in limited print runs featuring superior coloured wood engravings. The press was active between 1896 and 1914 and produced 32 titles in total, La Charrue D'Érable was the penultimate publication from the press. This is not only the most important book of the Eragny Press, but is also Camille Pissarro's only substantial illustrated book.

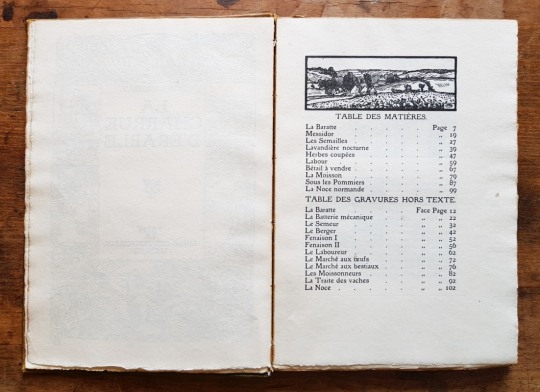

The book is illustrated with twelve full-page, colour wood-engravings drawn by Camille Pissarro and engraved by Lucien Pissarro, primarily printed in shades of peach, green, and/or blue from multiple blocks. In addition, there are numerous wood engraved vignettes, initials, and the title-page border by Lucien Pissarro.

Taken from Via Libri: The World’s Largest Search Engine for Old, Rare and Out-of-Print Books;

“Camille Pissarro exhibited in the first Impressionist show in 1874 and continued his association with the Impressionists for the next dozen years. He then adopted the style of Pointillism briefly, before reverting to an Impressionistic style of landscape painting. It was during this last period of his life that he made the drawings that would eventually result in La Charrue d'Érable. Although the book was not published until 1912, most of the blocks were cut and proofed by Camille before his death in 1903. Lucien Pissarro was trained as a painter by his father, exhibited with the Impressionists, and eventually became interested in book making. After settling in London, he and his wife Esther learned the arts of printing and book design from Charles Ricketts. The early books from Pissarro's Eragny Press were printed with type supplied by Ricketts. This book is printed in a typeface designed by Lucien Pissarro.”

The original book was bound in full limp green calf with gilt titling on the upper cover. The leather had begun to degrade on the copy I was due to rebind, especially on the spine section. There were calf paste-downs inside the limp cover, stamped in gold with apple patterns and a central “Livre Contemporain” monogram. The client was keen to keep these paste-downs in the new binding so I had to think of ways to achieve this. I did also enquire whether he wanted me to try and retain the paper endpapers opposite these leather doublures, they had a sort of ‘halo’ of the leather doublure pattern on them due to the acid from the leather affecting the paper. In the end I though that they were too brittle and damaged to transfer to the new binding.

In early 2011 the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford ran an exhibition entitled, “Lucien Pissarro in England: The Eragny Press 1895-1914”, I was able to buy a copy of the catalogue they published online with the same title in order to read up more about the Eragny Press. Lucien was sent to England by his parents where he fell in with a group of artists who were followers of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement. In the 1890s, William Morris founded the Kelmscott Press to produce exquisite, hand-made books. Lucien and his friends wanted to do something similar, and so for the next 20 years he laboured over the spasmodic production of 32 hand-crafted books with his wife, Esther.

I found it interesting to read that Lucien Pissarro had to wait a long while for the text to be written, it was delayed due to illness and other reasons. He therefore ended up making the initials before the text was written so the writer then had to begin his chapters with words which began with the letters that had been cut!

Although inspired by the Kelmscott Press, the woodcuts are very different to those done by William Morris. There were no floral borders in this text block, although the title page had some floral elements like apples on a tree with one of the chapters actually being called, “Sous Les Pommiers”, or “Under the Apple Tree”. I really liked the way that these branches looked so began to think of ways of incorporating these into the design for the cover.

The book is a quaint representation of rural French farming life. I lived in France for 18 months a few years back although unfortunately I didn’t become a fluent French speaker so I required some help deciphering the, 'Table des Matières'. I asked a French friend to help me translate the chapter titles which she did, although she was unsure about a couple of them as they were written in old French. Fortunately these gaps were filled by my French-speaking client. Alongside egg and cattle markets (Marché aux œufs/au bétail) and harvesters (Les Moissoneurs) the more interesting descriptions were:

Messidor: During the French revolution, the name of the months were changed. Messidor was the tenth month (from mid June to mid July).

Lavandière Nocturne: A ghostly spirit in the form of a washerwoman doing laundry in the river or pond seen at night. This is a bad omen, usually a herald of death. This is a widespread southern French folk-legend.

La Batterie Mécanique: In this context it is a mechanical thresher for grain.

The book was very easy to pull as the covering leather on the spine had degraded and the sewing threads were loose. The central sections therefore pulled away from the leather spine well and I carried out a couple of small repairs on tears using Japanese tissue and wheat starch paste.

Some of the sections within the text block were unopened, so the top edge of the sections had never been cut meaning that some of the 'hidden' pages in the original binding would have been hard, if not impossible, to read without tearing the paper.

Many books were sold with unopened pages, this may have been to save the publishers labour and money or to make the sections easier to sew as the pages wouldn’t move around like modern single folio gatherings if left uncut. The reason they were sold like this was that the purchaser/collector was supposed to take the book to a bookbinder of their choice (usually local) who would bind the book according to their personal taste, often the same leather and finishing for each book so that their library looked the same. This was the way books were brought on the market until well into the nineteenth century, until industrial bound books came into being, with their edges cut flush.

The original binding was simple limp calf, perhaps meant as a 'temporary' binding. Had the edges of the pages been cut, the bookbinder would likely cut them again when rebinding, each time taking more off the text block decreasing it's size. I made the decision to cut the top edges of the sections in order to make the binding function properly, but left the foredge and bottom edge deckled.

In researching the reason why books were left unopened I was directed to an interesting article entitled, “Uncut, unopened, untrimmed, uh-oh” from The Folger Library about the terminology behind it, having initially referred to the pages of my text block as ‘uncut’ I realise that they should have actually been described as ‘unopened’:

unopened: a book sold with the bolts uncut, to be hand-slit by the purchaser with a paper-knife. It is then said to be opened. Cf. uncut.

uncut: a book is said to be uncut if the edges of the paper have not been cut with the plough or guillotine. Cf. unopened.

The difference between “unopened” and “uncut” is significant for the history of reading: unopened leaves are a pretty good indication that a book wasn’t read when it was new. Uncut leaves, on the other hand, only show that the text block was not neatened up by having the edges trimmed to the same size.

I was inspired by the earthy pastel colours of the woodblock prints. I found a really interesting supplier of Bull skins in a wonderful array of colours, appropriately this was from a French supplier called Remy Carriat. The colour I opted for was a pale green called ‘Pistache’ which was the perfect match for the green on the title page and throughout the binding.

I paired it up with some 80gsm Japanese machine made paper called ‘Satogami’ in the colour Apricot which made the perfect colour palette.

The design was based on a repeat pattern inspired by the apple branches on the title page of the text block.

Rather than having apples on the branches over the whole book, I decided to divide the design in two and have apples on the branches one side and apple blossom on the other. I traced the leaf shapes through onto a piece of tracing paper, changing the placement of the apples for flowers for the other half of the binding.

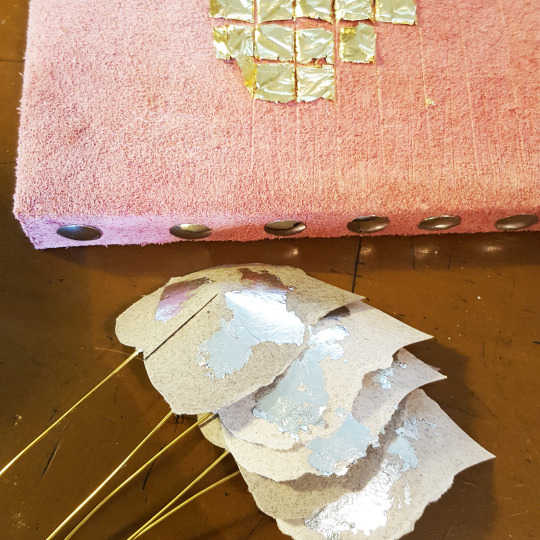

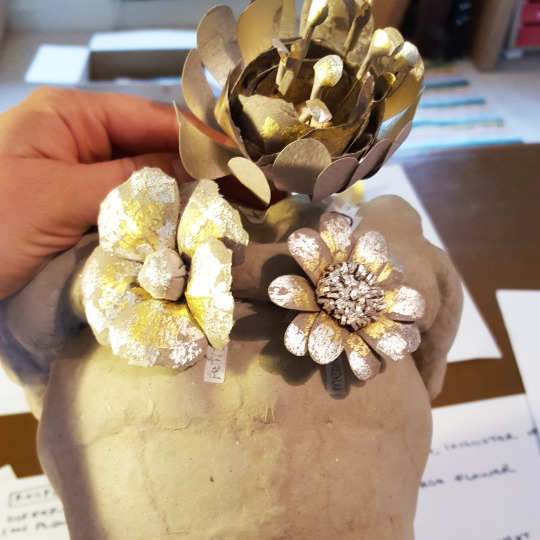

With the colour palette chosen I searched through my bag of leather off-cuts and parings for a variety of pieces to use for the onlays. I chose a selection of greens, oranges and peaches in both leather and suede in order to have a nice selection of different tones on the cover. The suede pieces were backed onto lens tissue to keep them stable.

I chose to use thin vellum for the apple blossom, cutting out multiple flower shapes. I then stippled some acrylic paint onto the centres to add some colour.

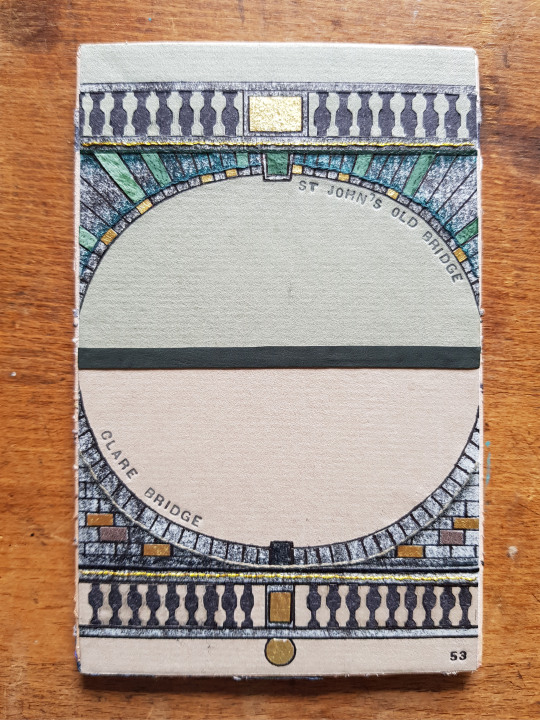

I first worked on a small piece of leather to make a sample board to test out the design. I make a sample board ahead of each of my fine bindings to test out colour combinations, this one is number 55 in my collection.

A piece of tracing paper with the design on was stuck on top of the pared leather at one side so it could be lifted up and down. The onlays were picked up with fine tweezers, PVA glue applied to the reverse and then they were stuck down in place using the tracing paper template as a guide for placement.

The sample board was then backpared on the reverse before being embroidered.

The completed sample board was an excellent match for the title page so I was very pleased.

Jumping ahead, but still on the subject of the sample board, the above picture shows the reverse of the board illustrating the endpapers and the doublures alongside the title page and the paste downs. Please read the next blog post for how the endpapers and doublures were created!

#bookstagram#bookshelf#reading#booklover#bibliophile#bookbinding#craft#leather#inspiredbynature#tooling#designbinding#artbookbinding#reliuredart#reliure#finebinding#leatherbinding#firstedition#hannahbrown#contemporaryembroidery#thread#bookcollecting#erangy#erangypress#pissarro#lucienpissarro#camillepissaro

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

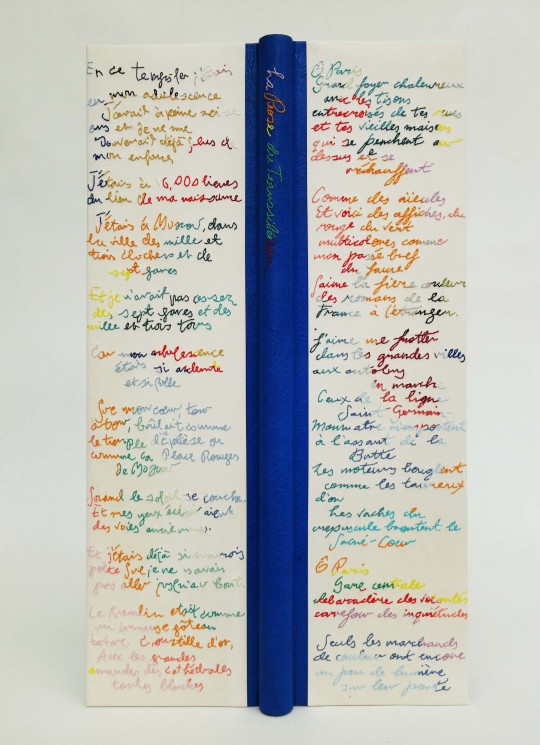

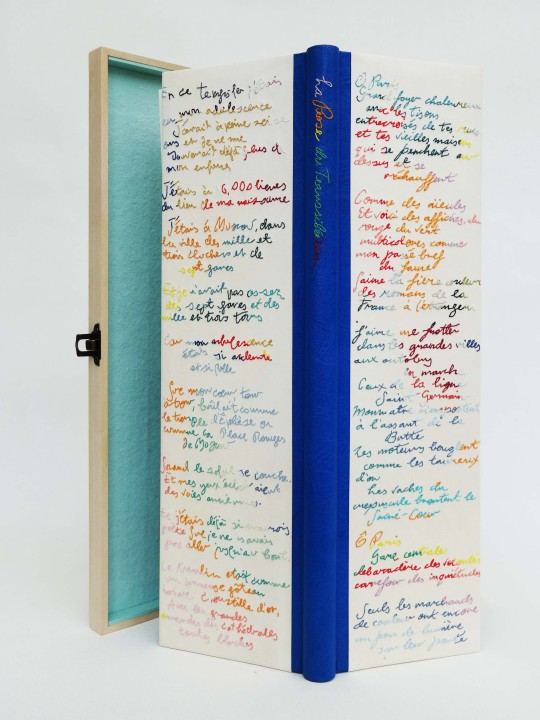

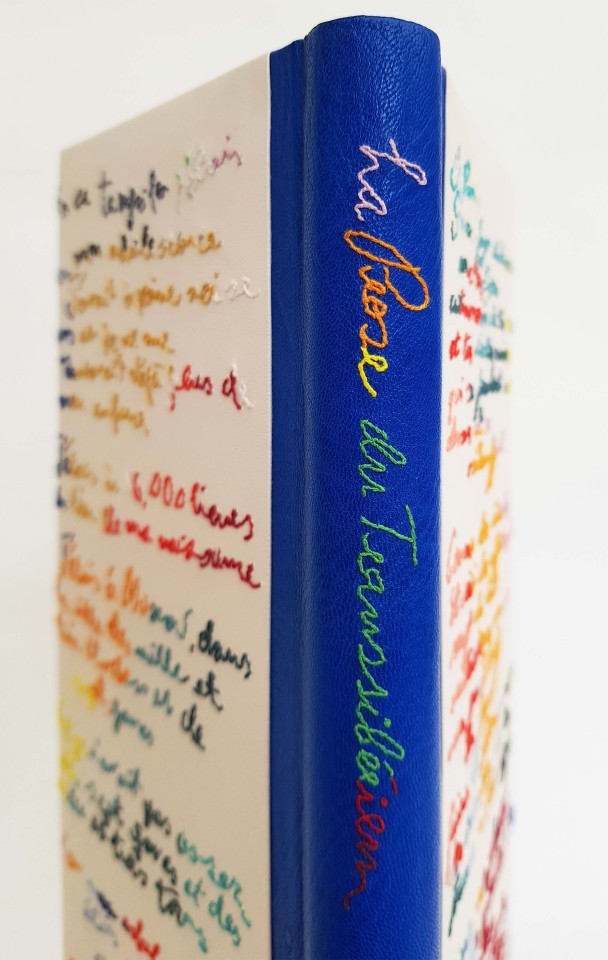

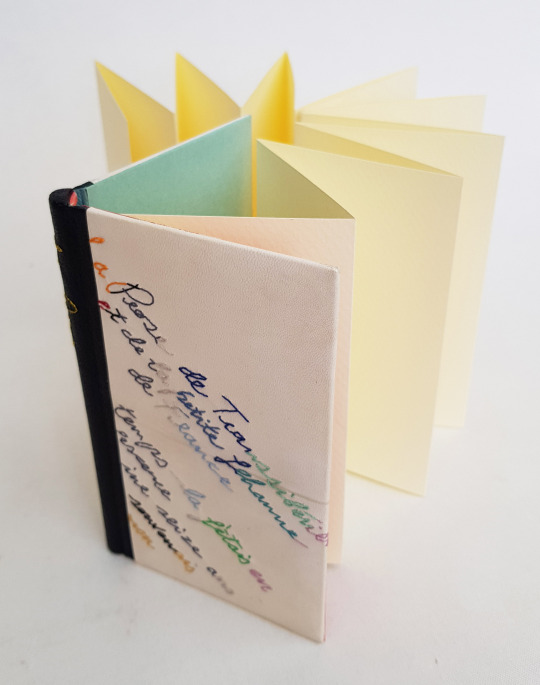

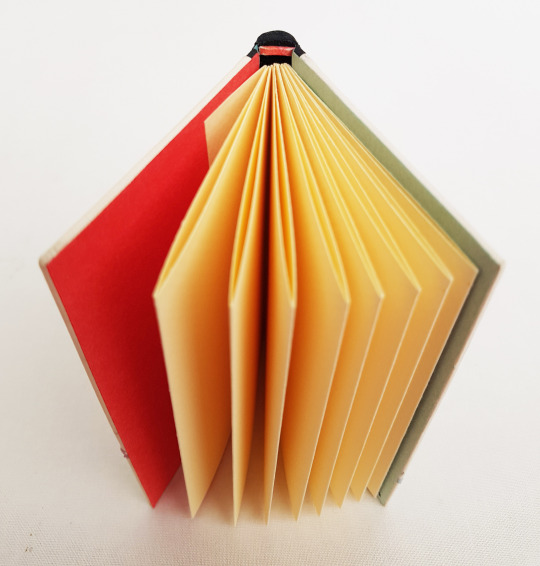

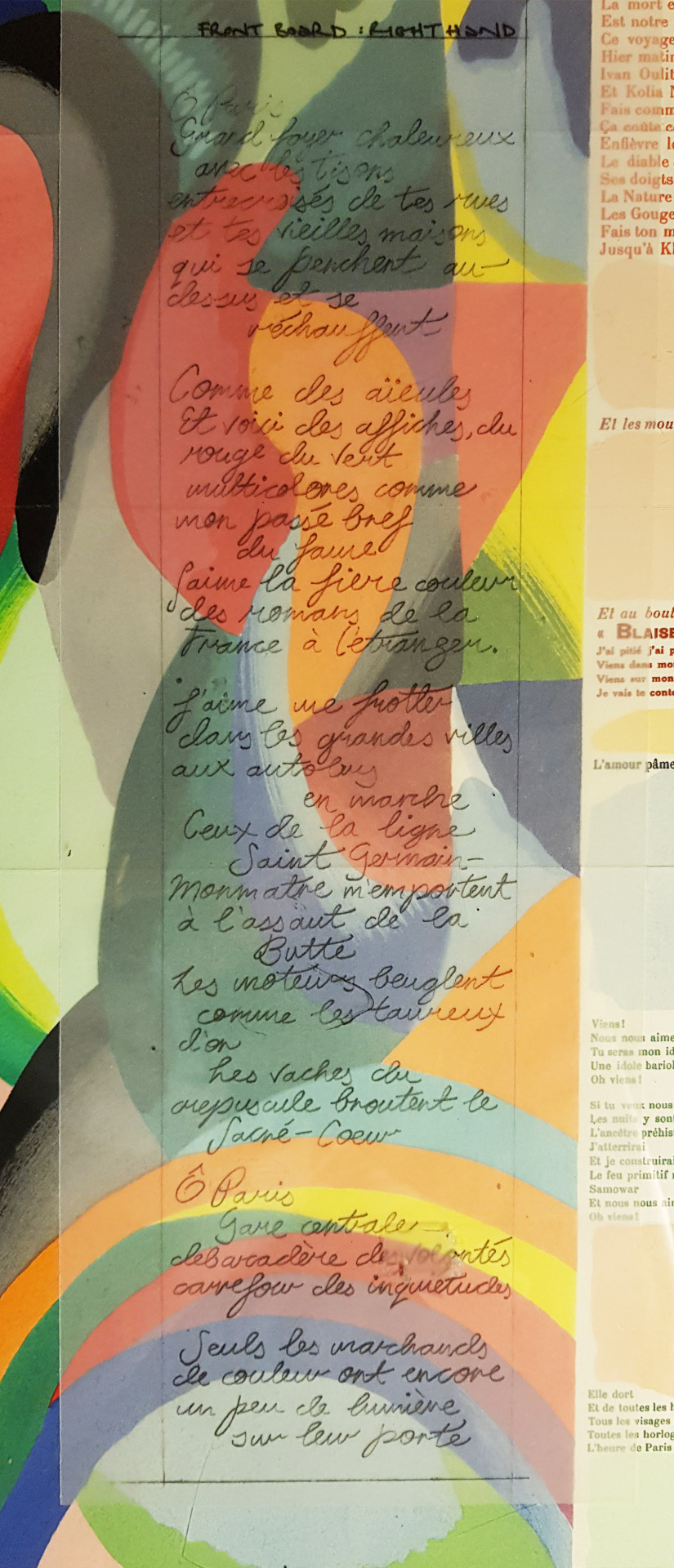

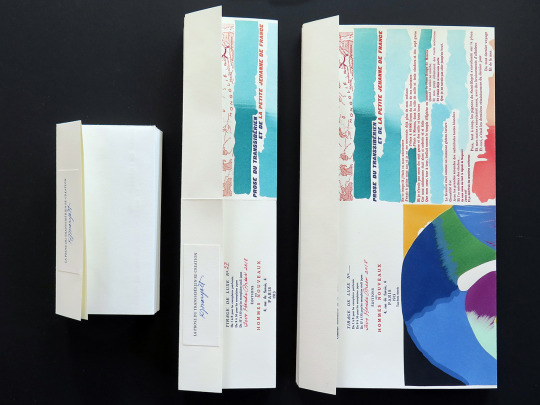

La Prose Part Five: Finished Binding

OPEN BOOK NEXT TO BOX (ABOVE)

It is always a wonderful feeling when a book is complete. However long it has taken from beginning to end, there is always a sense of achievement. The work doesn’t stop there though, it needed to be photographed and I still had my blog post to write about it.

It turns out that this blog post has been rather a long one! The fact that it is such an interesting project to have worked on with the recreation of such an spectacular original and all the background research that Kitty Maryatt put in to realising it, alongside the point that I had never worked on this structure of binding before, and also the editing of such a lot of images and stages to write about has turned this in to a five part post.

The book is also on my website here.

OPEN BOOK COVERS (BELOW)

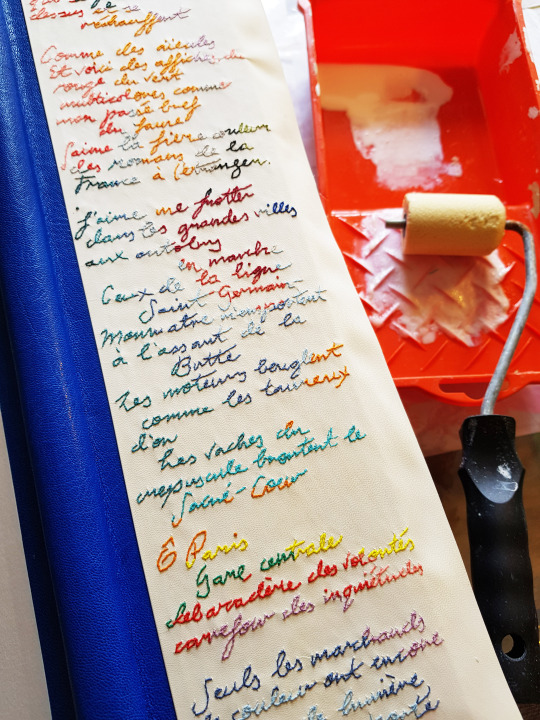

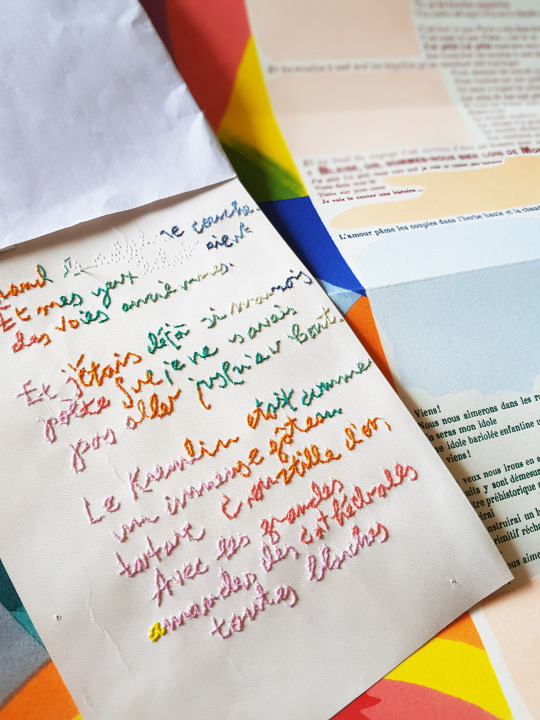

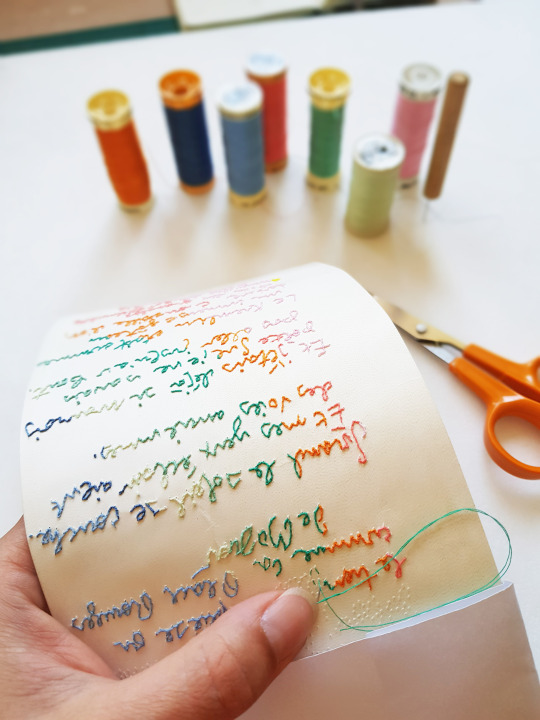

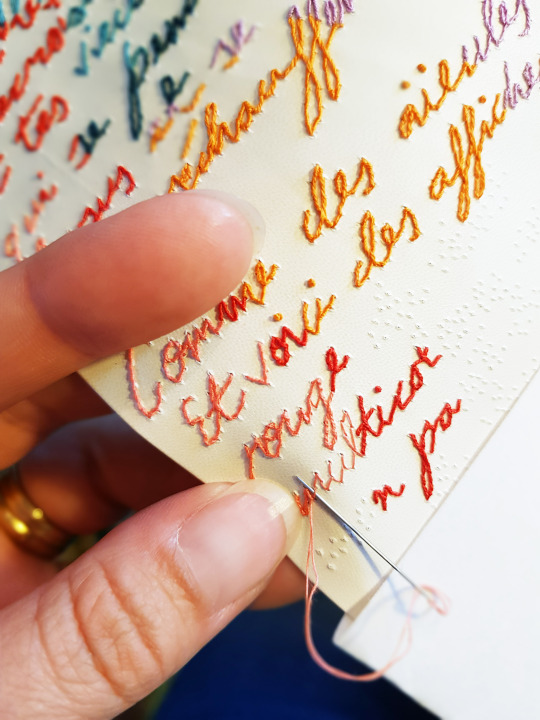

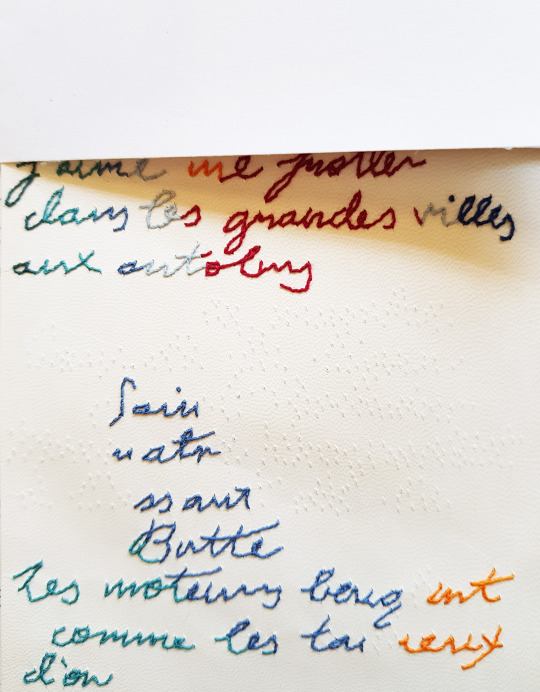

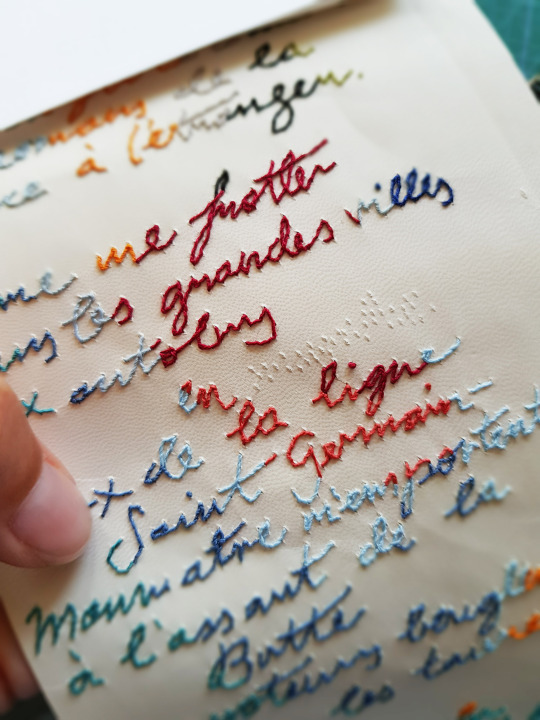

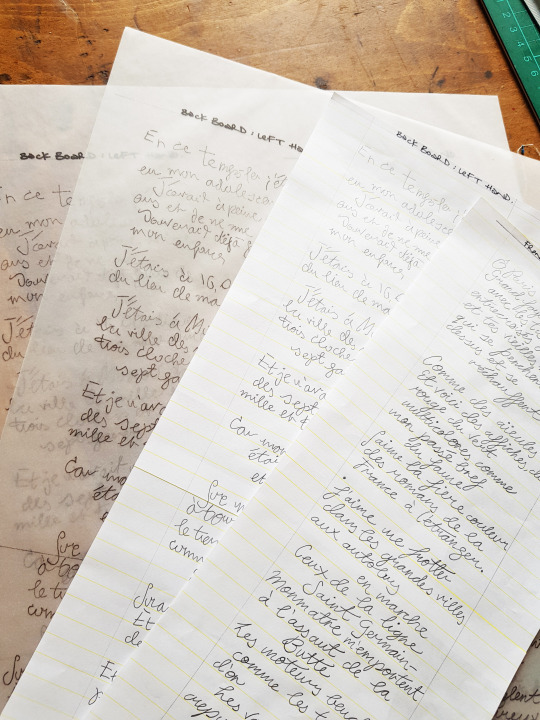

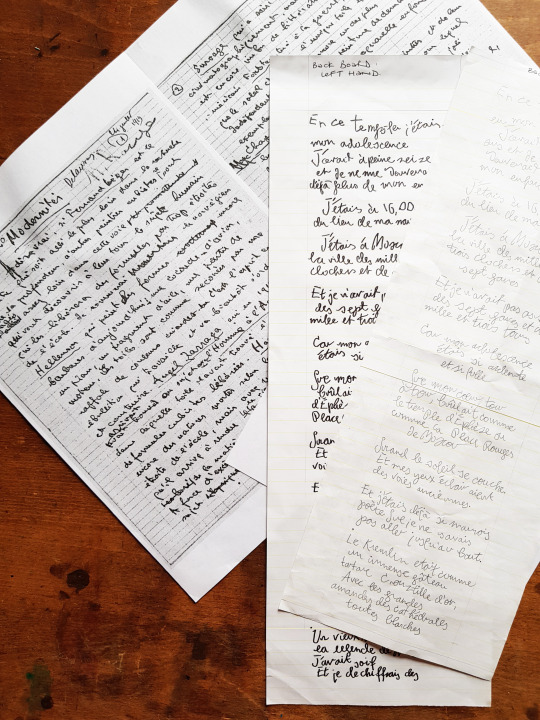

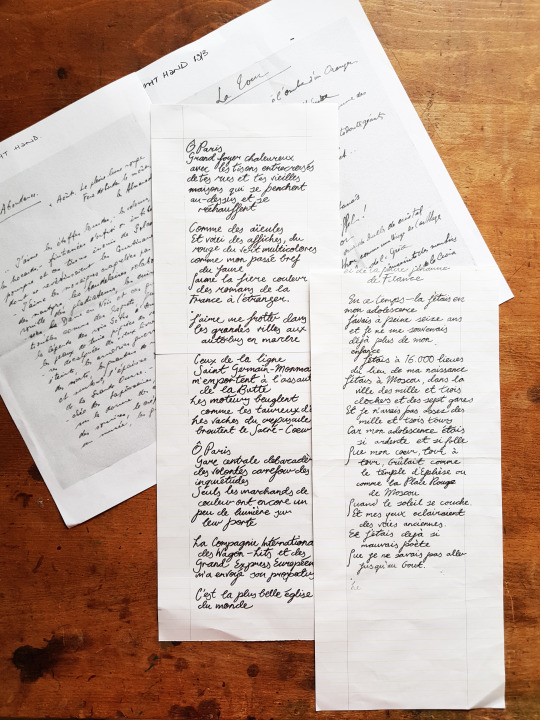

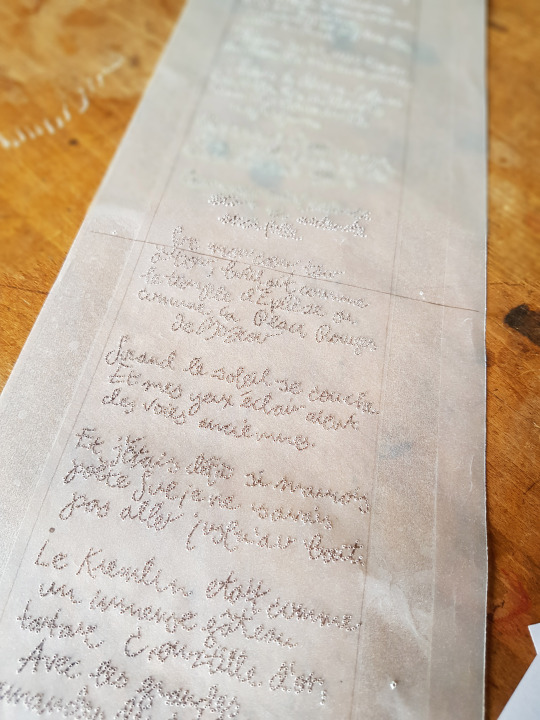

But what do the covers read? I took text from near the beginning of the poem for the back cover:

I was in my adolescence at the time Scarcely sixteen and already I no longer remembered my childhood I was 16,000 leagues from my birthplace I was in Moscow, in the city of a thousand and three belfries and seven railroad stations And they weren't enough for me, the seven railroad stations and the thousand and three towers For my adolescence was so blazing and so mad That my heart burned in turns as the temple of Epheseus, or as Red Square in Moscow When the sun sinks. And my eyes shone upon the ancient routes And I was already such a bad poet That I didn't know how to go all the way to the end. . The Kremlin was like an immense Tatar cake Crusted with gold, With great almonds of cathedrals all done in white And the honeyed gold of the bells… . An old monk was reading to me the legend of Novgorod I was thirsty And I was deciphering…

And for the front cover, a section towards the end. This was a rather apt section of text to choose given it included the words “rouge”, “vert”, “multicolores”, “jaune” and “d’or” - how appropriate for a colourful book!

O Paris Large glowing hearth with the crossed pokers of your streets and your old homes that hunch over warming themselves Like forefathers And here are the posters, red and green multicoloured as my brief yellow past Yellow the proud colour of French novels sold abroad. . I love to squeeze into moving buses in big cities Those of the Saint-Germain-Montmartre line bring me to the assault of the Hill The motors bellow like golden bulls The bovine twilight grazes the Sacre Cœur O Paris Central station last stop of desire crossroads of unrest Only the merchants of colour still have a little bit of light on their doors The “International Company of Sleeping Cars and Europeans Express Trains” has sent me their brochure It is the most beautiful church in the world

OPEN BOOK IN FRONT OF OPEN BOX (BELOW)

FRONT COVER AND TEXT BLOCK EDGE (BELOW)

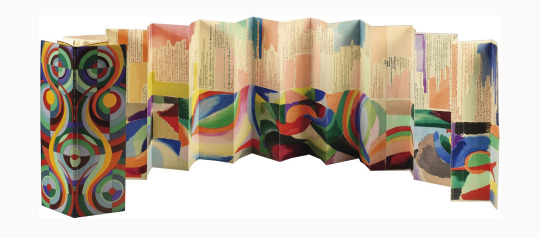

Although in the original, due to how the text block was folded, neither the text or the imagery could be seen until the book was completely unfolded, this was not the case for my binding. I was really thrilled once it was finished to see how well the coloured stitching harmonised with the strips of colour on the folded edges of the pages.

DETAIL OF BOOK ON TOP OF BOX (BELOW)

BOX LID (BELOW)

I really liked the fact that the box remained so simple, with just the title added on the top. I didn’t want to take away from the intricate a coloured embroidery of the cover that popped out as you opened the lid.

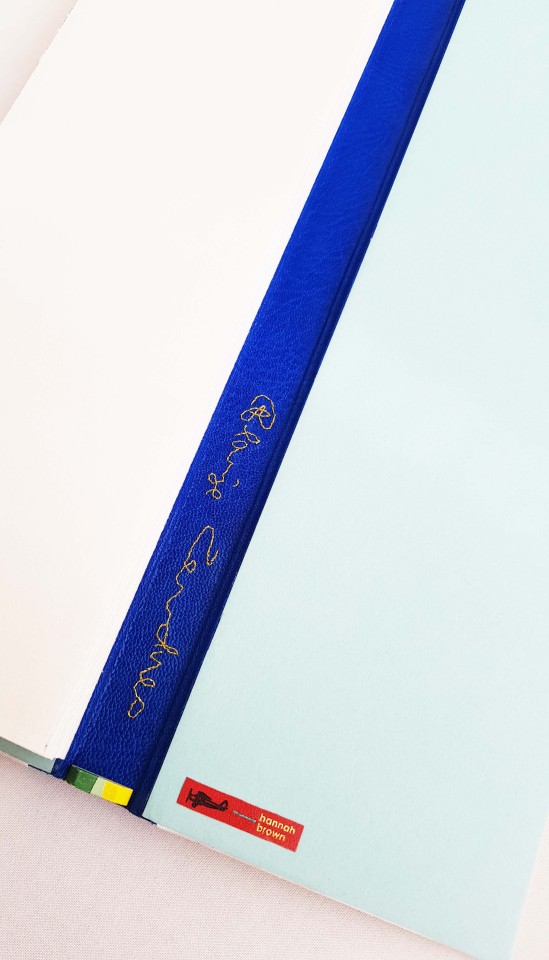

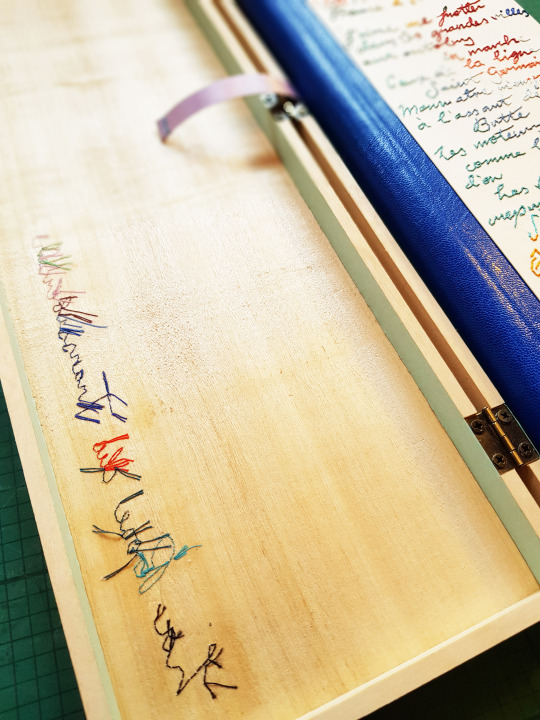

BLAISE CENDRARS SIGNATURE INSIDE SPINE (BELOW)

Blaise Cendrar’s signature was placed so that it would be a little added extra surprise as the book was opened. With embroidering it inside the spine it is hidden behind the concertina when the book is closed.

DETAIL OF OPEN CONCERTINA

The wonderful colours of the pochoir spill out as the concertina is unfolded. I was really pleased with how well the pochoir-covered end-caps worked as an extra design element of the binding.

SPINE TITLE (BELOW)

The title was embroidered, thankfully without any spelling mistakes (see below for details of my near disaster!).

EMBROIDERY DETAIL (BELOW)

From pink, to yellow, to green, to red, to blue and on and on, this truly was a book of multicolour.

THE OUTER BOX (BELOW)

The wooden box I had made was further housed in an outer conservation box. This was partly to protect it, and also so that the small accompanying concertina pamphlet that Kitty Maryatt had produced explaining about the project could live with the binding. This little booklet had a section made for it in the outer box so it could sit below the wooden box.

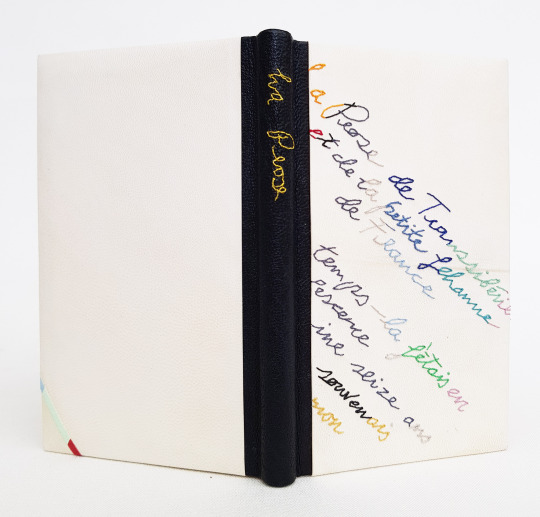

THE SAMPLE BOARD/BOOK

I have made reference in previous parts of this blog post to the sample board/book that I worked on ahead of the actual binding, I finish with some photos of this. I chose a darker blue goatskin for this spine with gold thread to embroider the title, this changed on the actual binding as I felt the dark blue didn’t match the pochoir.

I didn’t have quite enough vellum to cover the back board entirely so I pieced two bits together and masked the joint with a strip of the leftover pochoir.

SAMPLE BOARD/BOOK COVER EMBROIDERY

I embroidered the sample with writing at and angle, however decided to change this on the actual binding working horizontally. Thankfully, I had asked in advance whether it was okay to post images of some of my work in progress online whilst working on this project, both Kitty Maryatt and Neale Albert agreed. I was very pleased that this was the case as a French friend of mine spotted a spelling error on the sample book! Rather than “La Prose de Transsbérien”, it should have been “La Prose du Transsbérien”, another good reason for doing sample boards I guess - phew!

THE OPEN CONCERTINA OF THE SAMPLE BOARD/BOOK

The book was made so that when closed, the width and height were the same dimensions as my sample boards. Although of course it is thicker than a sample board, it can still sit in the same box as them in a wider slot.

This mini book is also going to have a second purpose, I have been meaning for a long while to make an index for my sample boards. Given this book is a sample board, and will therefore be in the box with them, I intend to use it’s pages to index all the other boards.

SAMPLE BOARD CONCERTINA PAGES

The front and back doublures of the sample book are different colours, initially I thought I would go for red doublures but in the end opted for pale blue to match the first spread of the concertina when opened.

BLAISE CENDRARS SIGNATURE ON INNER SPINE

Blaise Cendrar’s signature also appears on the sample book in red thread. This is sample number 54 in my ever-growing series.

The completed binding is now safely in New York. It is due to be shipped on to San Francisco to take part in the following exhibition alongside some other absolutely wonderful bindings of La Prose by other binders.

EXHIBITION at the San Francisco Center for the Book TITLE: Drop Dead Gorgeous: Fine Bindings of La Prose du Transsibérien Re-creation DATES: September 6 to October 6, 2019 OPENING RECEPTION: Friday, September 6, 2019, 6:00–8:00 pm LOCATION: San Francisco Center for the Book, 375 Rhode Island Street, San Francisco, CA.

The remarkable book by poet Blaise Cendrars and artist Sonia Delaunay, La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France, was produced by letterpress and pochoir in 1913. It was a landmark achievement for its time with its unprecedented format, avant-garde typography and abstract imagery, and remains vibrant and modern today.

Kitty Maryatt of Two Hands Press has been researching the production of La Prose du Transsibérien since 2012. In 2018, she debuted a new edition of 150 copies, which faithfully incorporates techniques and methods used in the original. At the same time, Maryatt and her underwriters commissioned fine bindings by notable design binders from around the world. These bindings, along with Maryatt’s La Prose du Transsibérien Re-Creation, have resulted in a traveling exhibition titled Drop Dead Gorgeous: Fine Bindings of La Prose du Transsibérien Re-creation.

Debuting in San Francisco, the exhibition will feature the work of twenty-two design binders, including Don Glaister, Monique Lallier, Midori Kunikata-Cockram and Kathy Abbott. Tools, materials, and supplemental material used in the creation of Maryatt’s edition of La Prose will also be on display. Upon closing in San Francisco in October, the exhibition travels to additional venues in the United States, Canada and England.

DOCUMENTARY SHOWING TITLE: The Re-creation of a Masterpiece: La Prose du Transsibérien. Documentary by Rosylyn Rhee. Los Angeles, 2019. DATE: Friday, October 4, 2019, 6:00–8:00 pm LOCATION: San Francisco Center for the Book, 375 Rhode Island Street, San Francisco, CA.

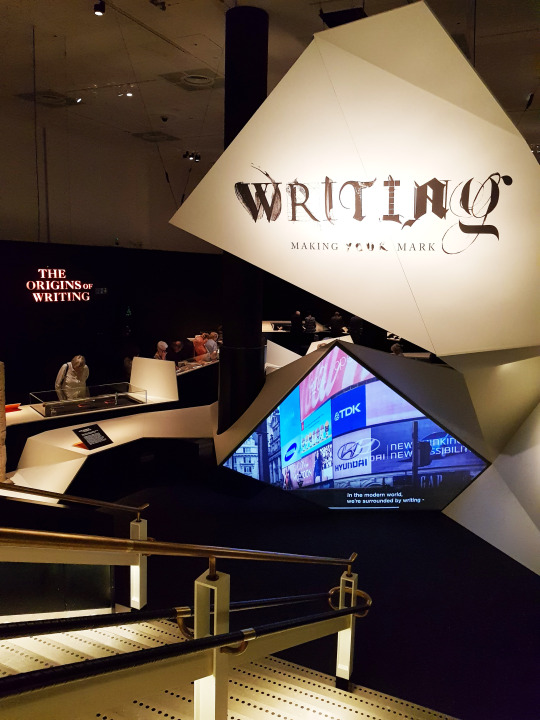

#la prose#le prose du transsbérien#sonia delaunay#blaise cendrars#two hands press#kitty maryatt#british library#making your mark exhibition#bookbinding#bookbinding commission#embroidered binding#vellum binding#reliure#reliure d’art#livre d’art#pochoir#stencilling#typesetting#handwriting#left handed#right handed#hannah brown#hannah brown bookbinder#shepton mallet#bowlish

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

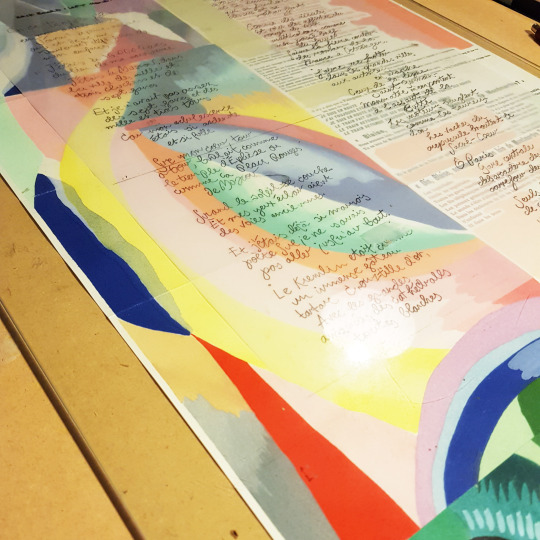

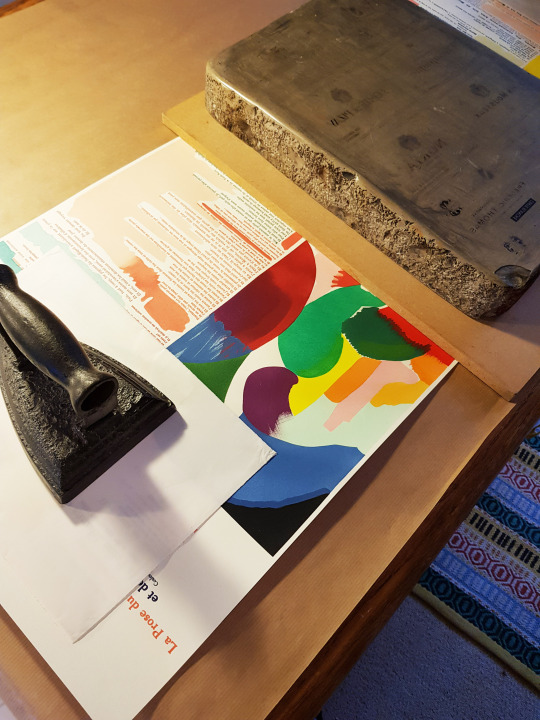

La Prose Part Four: Book Covering

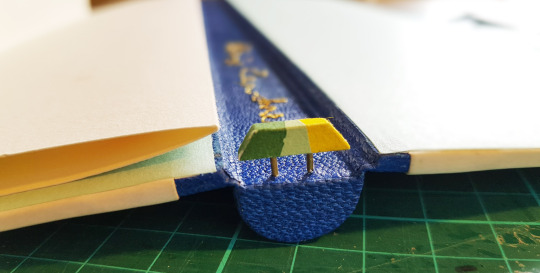

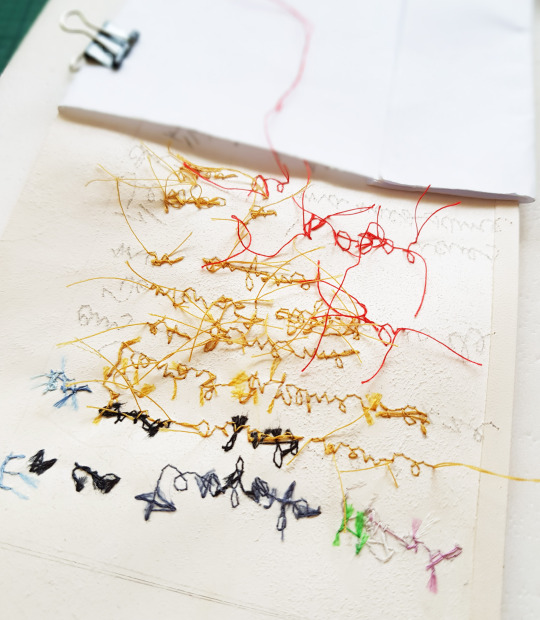

The day I completed the embroidery was a great feeling, but the next stage was getting the vellum stuck down onto the boards which was rather daunting. I always like to capture a photo of the reverse of the covering material before I stick it down, as it tells a story of how the front came to be, in some ways it is more interesting than what is on the surface!

I had experimented with gluing the vellum to stick to the sample book so I knew that the best adhesive was going to be a mixture of PVA glue and paste. I mixed this up in my roller tray and used a roller to apply it (I would usually use a paste brush for pasting out leather, but I found that it was best to use a roller for the vellum). The turn-ins were given a bit more PVA before turning them around the edges of the boards. The whole thing was lightly pressed under a weight and left to dry - I regularly changed the blotting papers to draw the moisture out.

I was really thrilled to see once dry that the vellum had gone down well. I gave it a good extra rub down through silicone release paper just to level out the embroidery threads.

Once the vellum on the cover was dry it was time to work on the inside of the boards. First I infilled with a layer of card, the same thickness as that of the vellum turn-ins. On top of this I glued down a layer of Zerkall, cut just slightly smaller than the overall size of the boards.

Once this was glued down in place, I sanded the Zerkall completely flat, so that there were no lumps and bumps.

Finally, one this was totally flat, I was able to glue down the paper doublure. I chose a colour to match the text block and this was glued down in place with PVA and a roller.

During the process of trimming the pages at the beginning of the project, there were a few off-cuts of paper left over with a little of the pochoir on them. I kept these not knowing whether I would find a use for them.

As the folded concertina wasn’t perfectly square on all four edges (it was seemingly impossible to get it so!), plus with this method of binding there was no need for sewn headbands, I decided to add some of my own. This would neaten up the look of the head and tail of the book and would add some more detail.

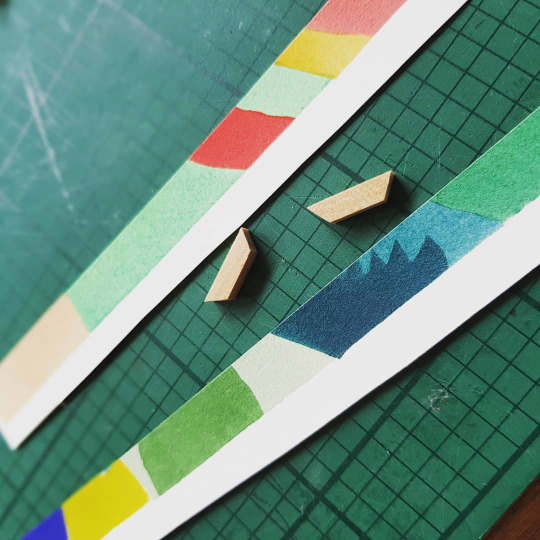

I began by cutting two small sections of square profile tulipwood to the width of the inner spine.

These were then mitred at both ends and paired together with the pochoir offcuts.

I delaminated the paper so that it was thinner, and covered the tulip wood in the coloured paper. I am now referring to these as “end-caps”.

I drilled two holes in both the end-caps and glued two brass pins in place. Corresponding holes were also drilled at the top and bottom of the inside of the spine, and the end-caps were secured in place.

At this point, I also glued the concertina into the case by tipping the tab that was left at the end of the folded concertina directly into the front board of the case, so that when positioned the pages were square.

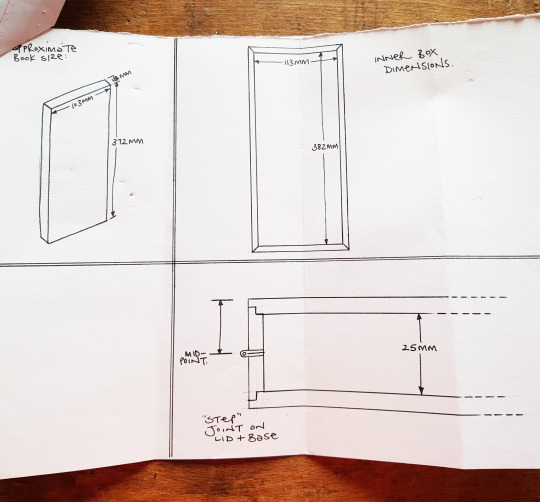

So the book was complete! Now time to move onto the box. I commissioned a wonderful woodworker to make a tulipwood box for me to the following dimensions.

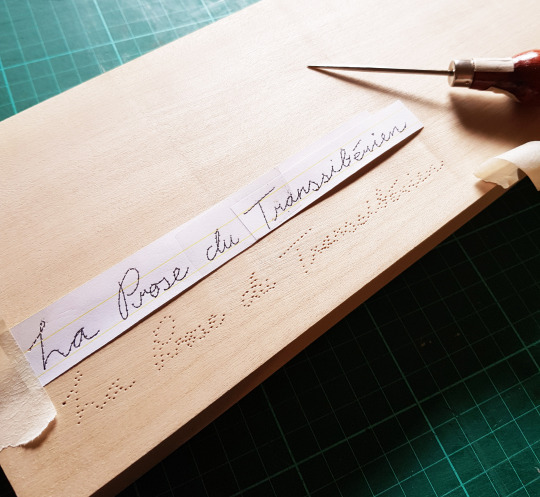

I wanted the title on the front of the box, and to carry the theme along I decided to embroider this onto the box lid. I used a bodkin to mark holes into the surface of the wood through a template, and then used a very fine drill bit in my Dremel to drill through the box lid.

I then used a fine needle and embroidered the title onto the lid in the same way i had done all of the words on the cover, first with a running stitch and then a whipping stitch. It was more difficult to do the whipping on the box top as there was no flexibility in the wood so I had a bit of trouble weaving the needle under the running stitch in places but I got there in the end.

To add a bit of extra colour to the title, I punched out some small circles from the leftover pochoir paper. I also cut a thin circle of wood out of the box top using my Japanese centre punch and then these paper circles were glued into them.

The thread tails were glued down on the inside of the lid. I then lined the inside of the lid and base of the box with felt which absorbed the threads underneath, the sides were lined with matching paper. A ribbon was attached into the bottom of the box to help lift the book out.

The final blog post shows the completed binding, plus images of the sample board/book I made up to test the process out on, “La Prose Part Five: Finished Binding”.

#la prose#le prose du transsbérien#sonia delaunay#blaise cendrars#two hands press#kitty maryatt#british library#making your mark exhibition#bookbinding#bookbinding commission#embroidered binding#vellum binding#reliure#reliure d’art#livre d’art#pochoir#stencilling#typesetting#handwriting#left handed#right handed#hannah brown#hannah brown bookbinder#shepton mallet#bowlish

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

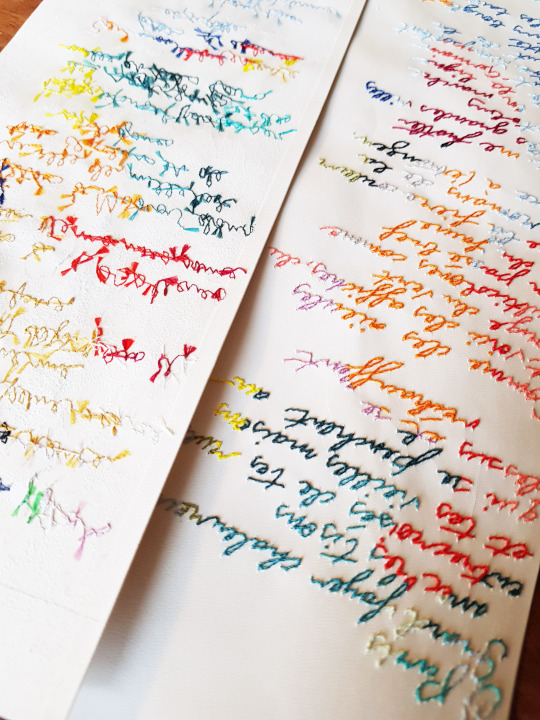

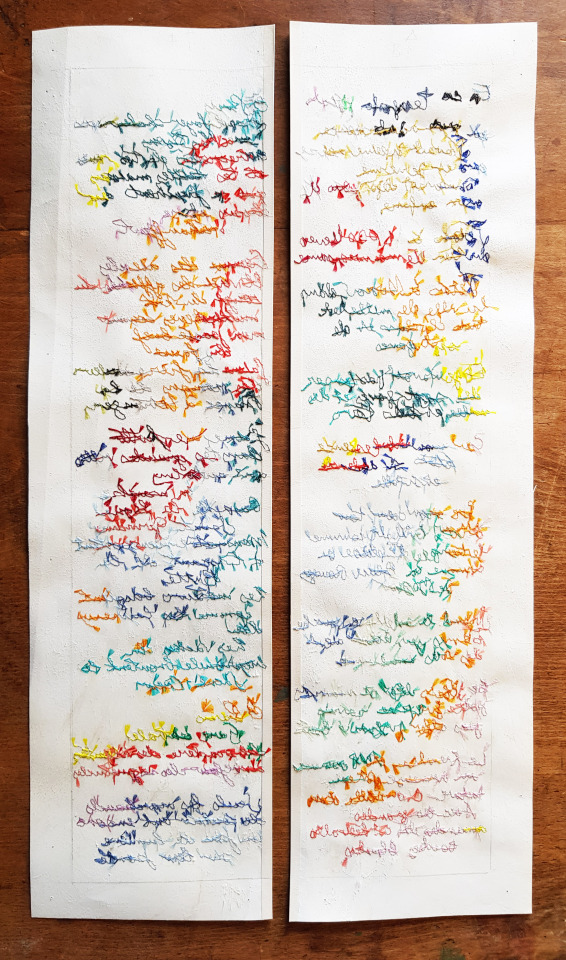

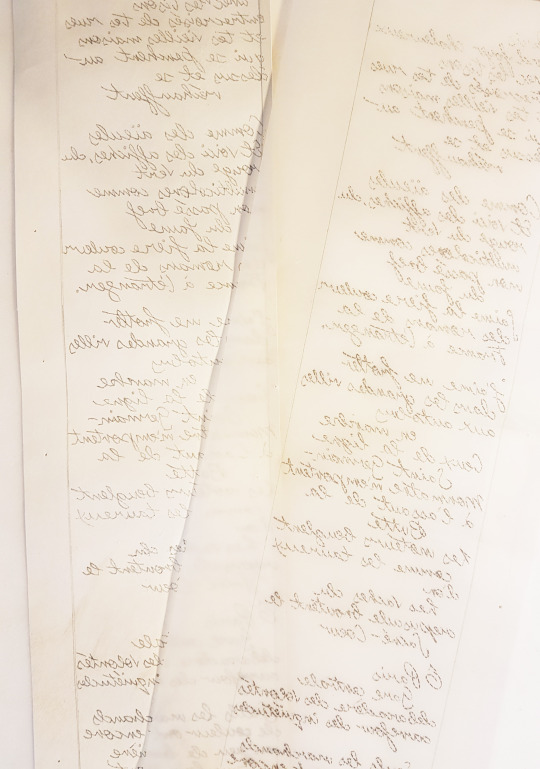

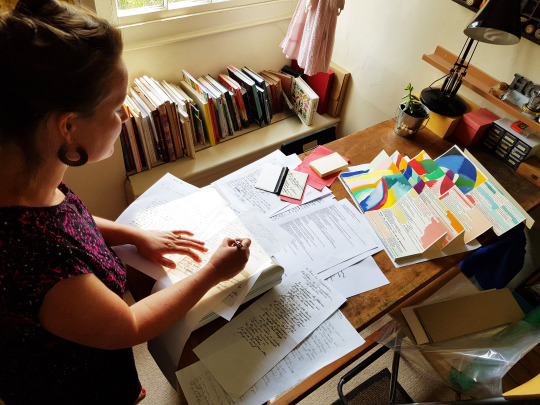

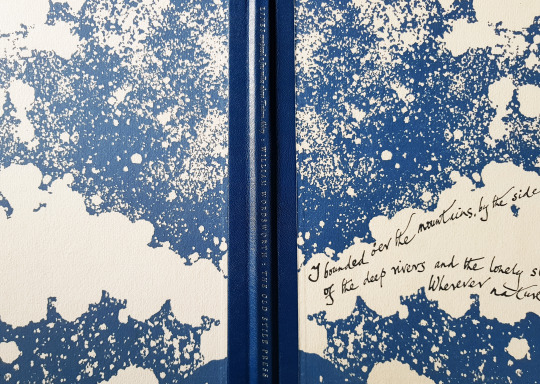

La Prose Part Three: Embroidery

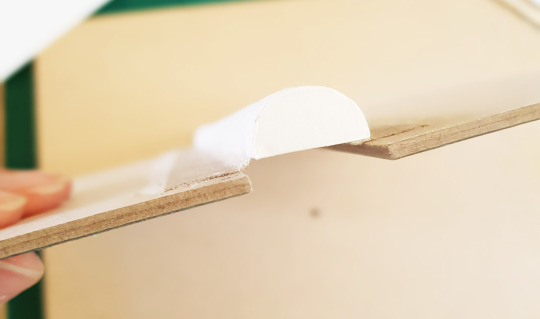

I marked out the size of the boards on to the back of the vellum. As I didn’t want a cut edge to be visible on the edge of the vellum that would be overlapping the spine leather on the cover, I folded an edge over by about 5mm and glued it down. The plan was to butt this folded edge up with the top paper lamination that was glued to the outside of each of the cover so once glued down this would be flush.

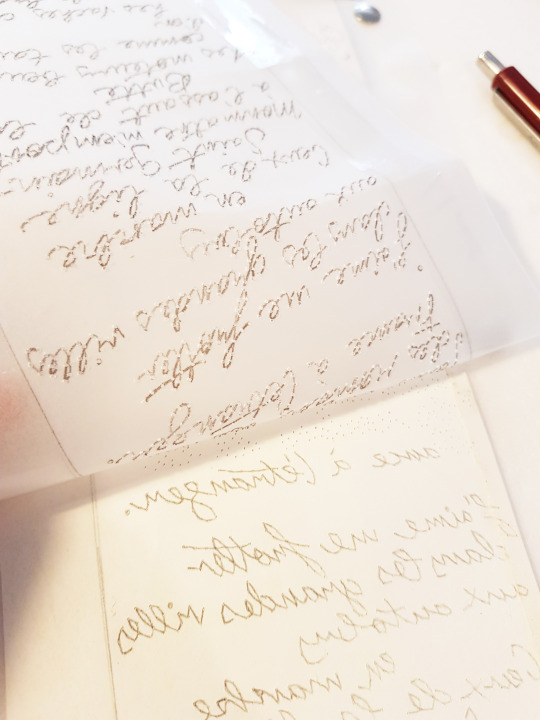

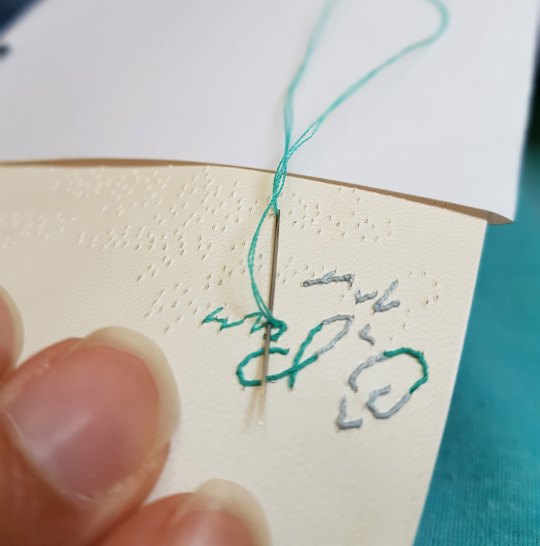

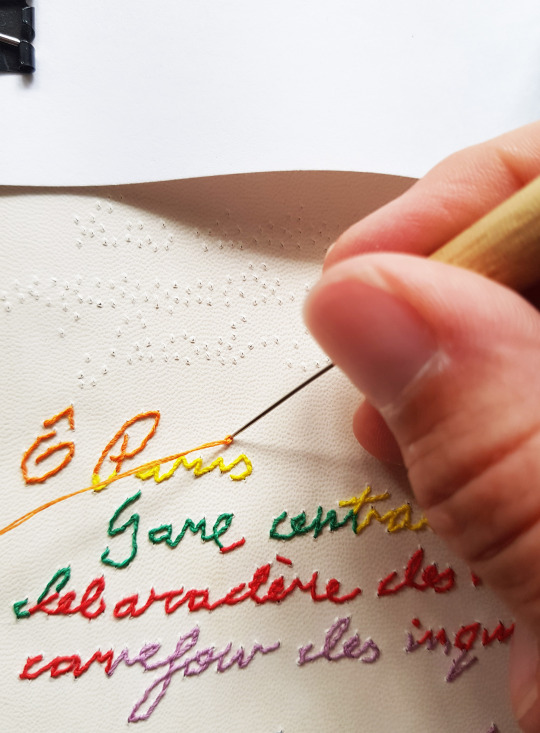

Initially I secured the vellum, face-down, onto a piece of Plaztazote foam, I then pinned the tracing paper template down on top of it in the correct place and pricked through hundreds and hundreds of holes at regular small intervals along the flow of the writing.

The great thing about using the vellum was as it was a lot thinner and stiffer than leather, the pricked holes were really visible once I had made them.

The next arduous task was to remove the tracing paper template and join together the dots making up the the words in reverse (obviously working back to front as this was on the back of the leather - very confusing!) so I knew which direction my embroidered threads needed to go.

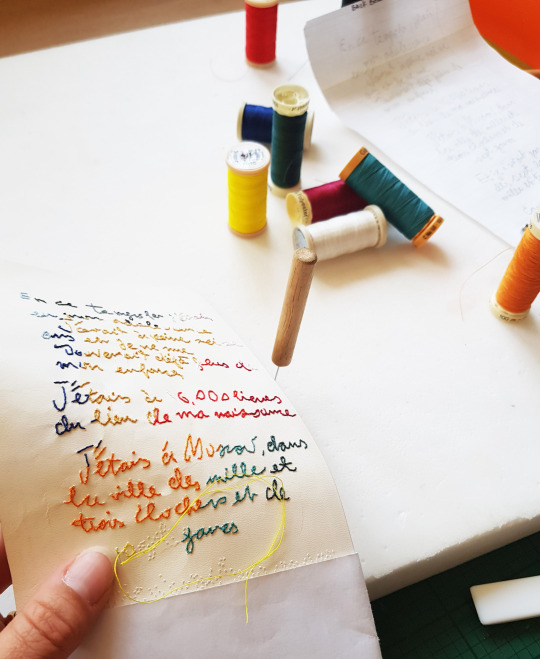

The plan from the beginning with the embroidery was to use threads that matched the colours of the pochoir as closely as possible. Having matched these and made a chart on a photocopy the time had come to start the the embroidery process.

Didn’t however just want to use a random selection of the colours for each of the words. I therefore laid down the tracing paper template on top of the actual pochoir, with a layer of glass on top, and worked directly from the colours on this.

I chose different parts of the pochoir the front and back to get the best mix of colours possible.

And so the embroidery could begin! I got comfy and spent the best part of two weeks sewing all of the words in place. I must admit, I did start to wonder why I had set myself such a mammoth task as the hours clocked up...

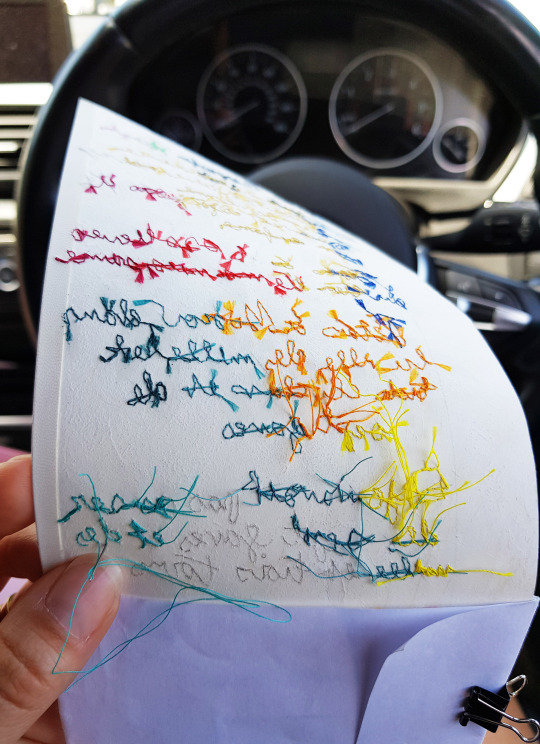

I made a paper sheath to hold the vellum is as I was working on it. As the pieces were so long and thin I didn’t want the end I wasn’t working on to get dirty or marked in any way. This was held in place using a small bulldog clip.

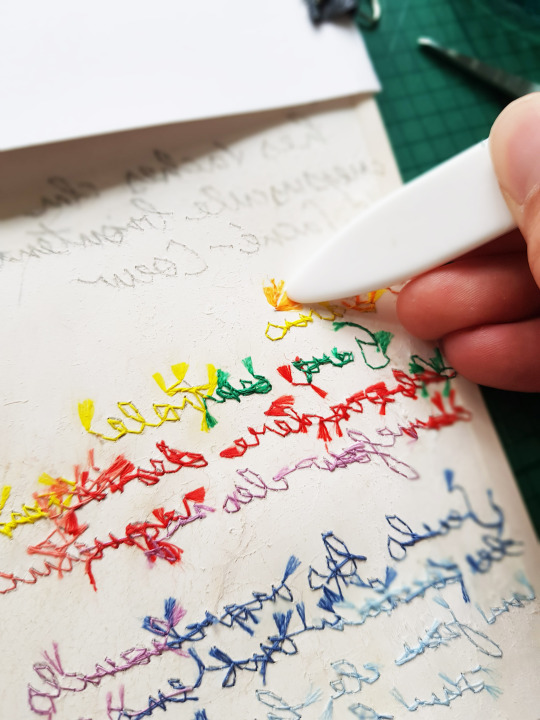

With lots of stitches on the front, of course this results in lots of loose threads on the back. I periodically went along and trimmed these tails and glued them down to the reverse with PVA.

I worked in a few sentences at a time, having the correct colour threads available to me to quickly interchange colours.

I even stole away some time on a weekend away to do some more sewing: embroidery on tour! Obviously I wasn’t actually driving at the time of taking this photograph...

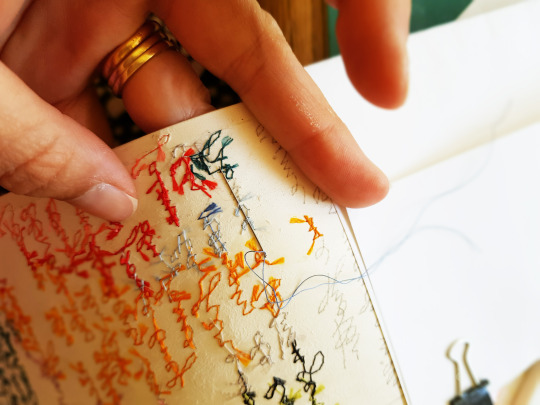

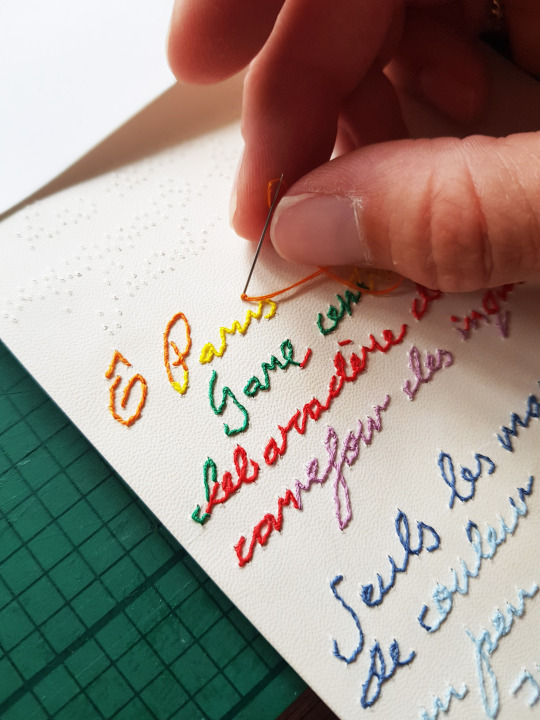

Each word was initially built up by joining the holes with a running stitch, using one strand of embroidery thread. Once the outline of the word was complete I then went around each of the running stitches with a whipping stitch, two strands in thickness.

So eventually all of the words were made up with a whipped running stitch. The needle creating the whipped running stitch did not enter the vellum at all, apart from where it started and finished at the beginning of a word.

Some sections of the text were more complicated than others, requiring numerous colour thread changes. Whereas some I had quite a bit to do just on one colour. It was more time consuming having the change the threads regularly.

I mentioned previously that I had turned over the cut edge of the vellum. On both the front and back covers, some of the words were placed that they were to be sewn on top of this double thickness. To avoid bulk on the back, I carefully cut away some small channels in the turned over vellum, where the stitches were going to fall on the back, in order to absorb the threads so that this would lie flush once glued to the text block.

I employed a couple of different methods of securing the loose threads down to the reverse of the vellum. Once I had finished with a colour, if there were suitable threads to go through on the reverse, I pushed a needle through behind them, thus securing the tail of the thread and I could cut it off.

This image shows the completed back embroidery, but with all of the front still to go...!

I mainly used Gutermann 100% polyester threads as they gave me the best colour matches. I am really lucky that in the town I live in (Shepton Mallet in Somerset, UK), there is still a haberdashery shop - they are so few and far between these days. It was absolutely key with this project to be able to see the threads in person before buying, matching the colours and buying threads online would have been much more difficult. I carefully packaged up my folded La Prose concertina at the start of the project and walked the ten minutes into town with it, into the haberdashery shop, to see first hand what colours I needed.

When it came to “dotting all the i’s”, I used two strands of thread. I pushed the needle through from the back and tied it into a loop.

Using the end of my needle pricker, with the very point of the needle placed in the centre of the loop thread against the hole in the vellum, I pulled the knot tight. In doing it like this, the knot tightens down the length of the needle pricker tight to the surface of the vellum creating a neat knot.

The needle was then pushed back though the vellum, through the same hole that it came out of. As the knot had been tied and there was extra bulk in the thread it wouldn’t pull back through.

The second method I employed for securing down the thread ends is pictured here. I cut the tail of the threads short and then frayed out the end using my needle pricker. This was then glued down with PVA and rubbed with a teflon folder. The whole way through the process I was aware that I wanted to create as little bulk of thread on the back as possible. As the vellum was so thin in comparison to standard leather I would use for a fine binding, any threads on the back were going to be partly visible and not as absorbed as much into the covering material.

After two weeks of embroidery, the end was nigh!

And then I was down to just one word, made up of 43 holes, 42 running stitches, and 21 whipped stitches...I could se the light at the end of this very long embroidery tunnel.

I didn’t count the number of words on the front and back cover, or try and calculate the number of stitches I made, but it would most certainly be in the hundreds of thousands!

The next part of the blog is “La Prose Part Four: Book Covering” and it details how I got the vellum onto the boards.

#la prose#le prose du transsbérien#sonia delaunay#blaise cendrars#two hands press#kitty maryatt#british library#making your mark exhibition#bookbinding#bookbinding commission#embroidered binding#vellum binding#reliure#reliure d’art#livre d’art#pochoir#stencilling#typesetting#handwriting#left handed#right handed#hannah brown#hannah brown bookbinder#shepton mallet#bowlish

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

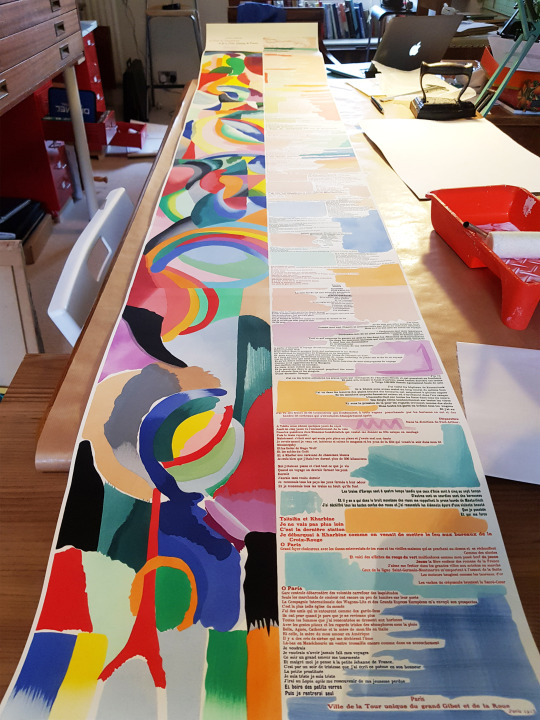

La Prose Part Two: Structure

With this binding came a number of challenges. Having overcome the gluing and folding of the beautifully printed sheets, how was I actually gong to bind them? I had never bound a concertina book before so this was going to be a first.

From the very beginning my thought was to create a false round spine which I would attach the boards to and the concertina would be attached inside it somehow. I wasn’t able to tell how the Paul Bonet version had been bound from the image I had seen but guessed this would have been done using a similar approach.

For each of the fine bindings I do I work on a sample board beforehand to test out ideas, colours, threads etc. For this binding, given I was unsure of the binding structure too I decided I make a mini version of the binding, the size of my usual sample boards. Photos of that will appear at the end of the run of these blog posts but that is what I used to test out the binding method of the full-size book.

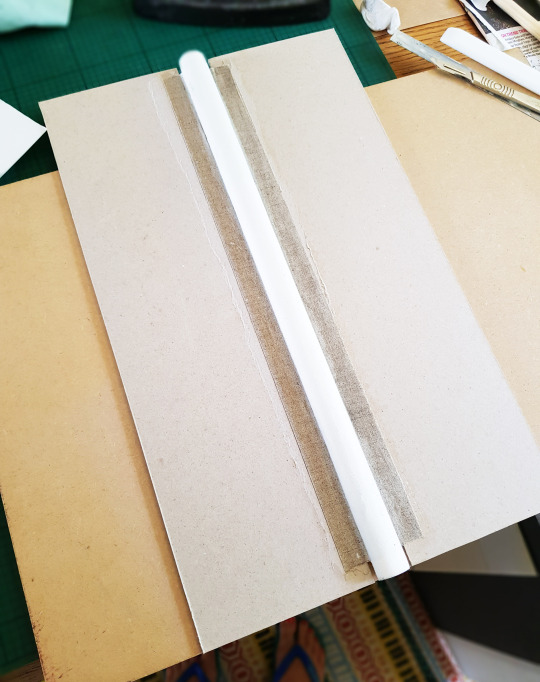

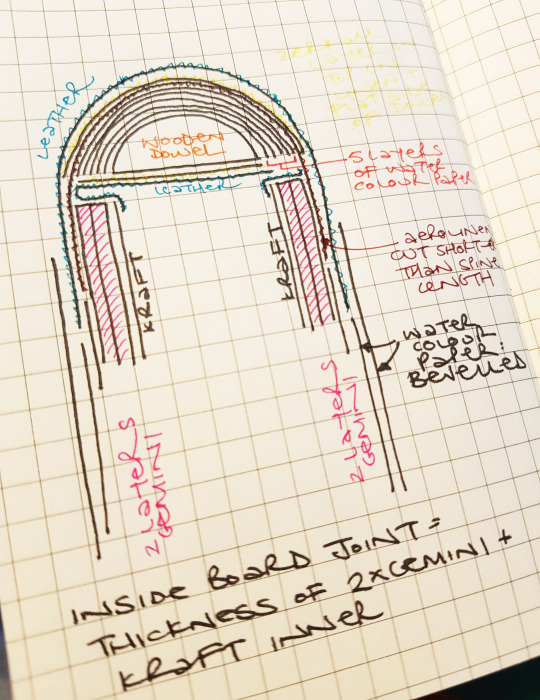

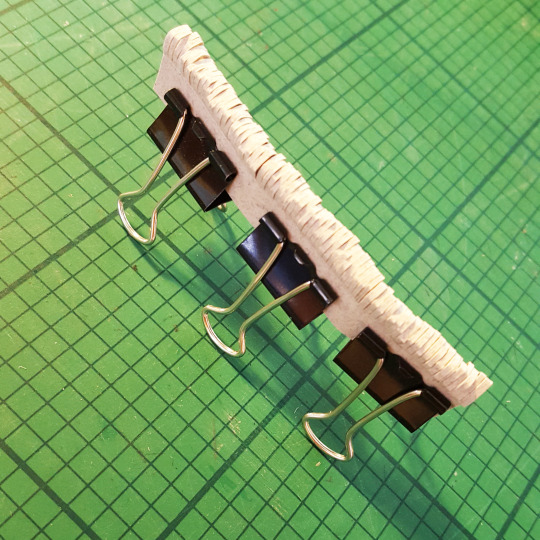

I started off with a half-round wooden dowel, the dowel was 15mm across but I needed to build this up to 20mm across to allow for the thickness of all the folded pages, plus a bit extra. I stuck the flat edge of the wooden dowel to the edge of a pressing board with double sided tape (so I could remove it again!) and put the board into a laying press. I cut a piece of 300gsm watercolour paper to size, glued it up and then positioned it on the round of the wooden dowel. I held it in place by covering it in a layer of silicone release paper and holding this down using a series of bulldog clips (pictured above).

This was repeated five times, and then I glued a layer of Aerolinen on top (slightly shorter than the length of the spine) followed by a piece of Zerkall.

Once dry I sanded the spine to get rid of any lumps and bumps. I had already laminated up the boards using two layers of 1mm Gemini board, with a layer of archival Kraft on the inside. Further laminations were to be glued on the outside of the boards once I had joined the spine piece to them.

I glued the Aerolinen to the boards with an equal space at the front and back to allow for the leather joints to be stuck in at a later stage. The boards were then lined on the outside with a layer of card to the same thickness as the Aerolinen.

The end of the false spine was “capped” with a piece of Zerkall cut to the same shape.

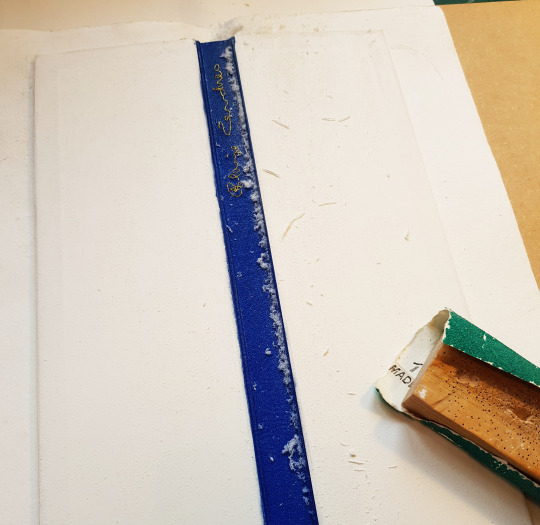

Once the book cover had reached this stage I was able to work on covering the spine with leather. I pared some blue Harmatan goatskin to about 0.4mm in thickness and thinned the leather more along where the board joints were going to be.

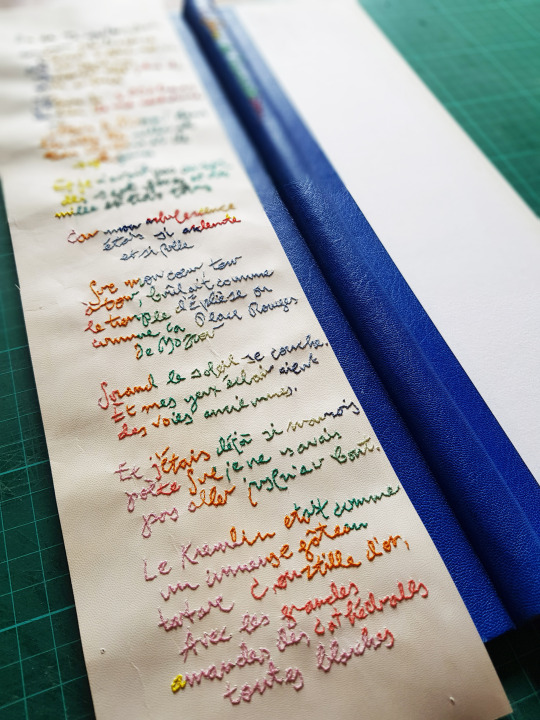

As I knew the covers were going to be entirely embroidered, I wanted to also embroider the title on the spine too. I made a pricking template of the book title and laid this down in reverse on the back of the spine leather centrally. I pricked through with a needle pricker and then joined the dots so I had lines to work from with the embroidery.

I laid the title writing down over one section of the pochoir colours and worked my way along changing the thread colour at the point where the pochoir colour also changed.

It resulted in a multicoloured title on the spine. The stitches were each done using a running stitch. Once the word was complete I ran around each of the individual stitches with a whipping stitch to make them cleaner and sharper.

Once this embroidery was complete it was time to stick the leather to the spine. I thinned out the very ends of the leather that were going to be turned over the spine ends, applied a mix of paste and PVA and then stuck the leather down. I had scrap boards of the right thickness held in between the front and back boards to keep them perpendicular to one another during the covering process.

The leather was then turned down onto the spine ends (I cut out some wedges of the leather first to rid some of the bulk) and inside the boards. Once dry I filled in the semi-circular void with a small piece of leather of the same thickness and sanded the whole lot flat. This was then capped with a thinly pared piece of the same blue leather.

The inside of the spine received similar treatment. I wanted to incorporate a left-handed signature I had found of Blaise Cendrar’s so decided to embroider this on the piece of leather that was going to cover the inside of the spine - a little surprise to find when opening up the final binding! This was embroidered in metallic gold thread. This was pricked through the leather in the same way as the spine title.

The edges of this strip of leather were pared very thin so that when the piece was stuck down the edges formed a thin layer of leather over the inside board joints.

A piece of watercolour paper was butted up to the edge of the spine leather and a piece stuck to the front and back boards. The watercolour paper and the leather were the same thickness resulting in a uniform thickness across the joint that they met.

Some thinner layers of card were then stuck on top of this, overlapping the joint of the leather and the watercolour paper underneath by about 5mm.

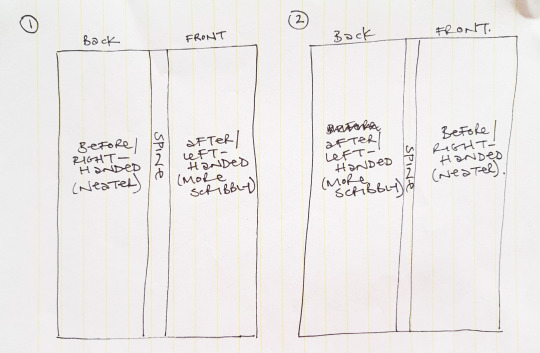

As layers started to get stuck together I thought it was important to make a diagram of what was going on within the laminations, in order to remember in case I wanted to repeat the process again!

I had left the width of the boards over-long just to be on the safe side. Once the spine was covered in leather it was possible to put the folded concertina in place to find out where I needed to trim the boards to to get an even square.

Finally, the boards were bevelled using a palm sander and then some sandpaper around a wooden block. The below image shows the difference in the thickness of the edges of the boards before and after the bevelling process. The thinner sanded edges on the left look more refined than the chunky ones on the right.

I wasn’t sure what material to use for covering the boards at first. Initially I thought I would like to use suede, however when I tried to embroider the words onto this it wasn’t very clear to see as the texture of the surface was too fluffy.

I had a lovely small vellum skin that I bought at the Society of Bookbinders Conference about 10 years ago that had been sat in my plan chest since then. It turned out to be the perfect size for this binding, plus it was very clear to see the embroidered writing and the prick-holes I made through the template were clearly visible on the surface. My only reservation was I had never used vellum before, I had no idea how it was going to react when glued but there is a first time for everything and that is what the sample board/book was for - to test unknowns like this out!

Once I had identified the covering material, I took a photocopy of part of the pochoir and cut small lengths of the appropriate coloured threads I had found/bought to make sure I had a corresponding one for each colour. I cut a little off the end of each reel and stuck to the photocopy.

The next blog post will explain how I got the below writing templates onto the vellum covering material and I will take you through the colourful embroidery process. The next post is titled “La Prose Part Three: Embroidery”.

#la prose#le prose du transsbérien#sonia delaunay#blaise cendrars#two hands press#kitty maryatt#british library#making your mark exhibition#bookbinding#bookbinding commission#embroidered binding#vellum binding#reliure#reliure d’art#livre d’art#pochoir#stencilling#typesetting#handwriting#left handed#right handed#hannah brown#hannah brown bookbinder#shepton mallet#bowlish

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

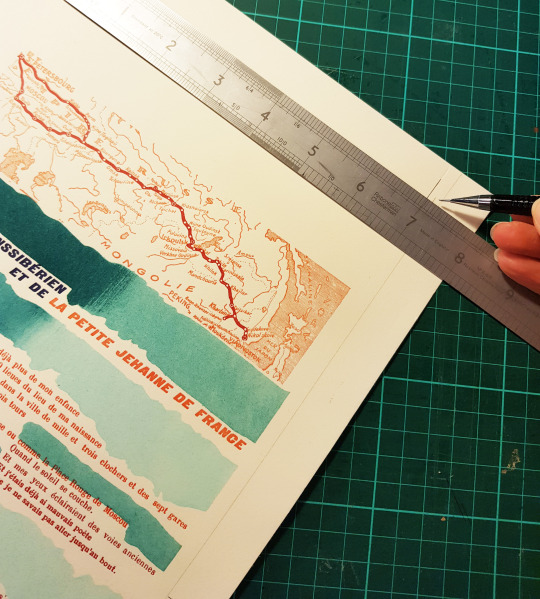

La Prose Part One: Recreation and Research

What an exciting project I have been involved in through my most recent bookbinding commission: the recreation of La Prose du Transsbérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France - the remarkable book by poet Blaise Cendrars and artist Sonia Delaunay. Sonia and Blaise first met in January of 1913 and formed an instant friendship, producing this book by letterpress and pochoir in 1913. The original book was a landmark achievement for its time and remains vibrant and modern today.

The recreation project was conceived by Kitty Maryatt, the proprietor of Two Hands Press in Playa Vista, California since 1974. In 2017 she decided to publish the recreation with the help of underwriters. Kitty has created a blog of her own documenting her journey through the process of recreating 150 editions as closely as possible to the original book by using letterpress and pochoir. Her blog is totally fascinating can be found here. It is thanks to this blog, plus some additional information that was printed to be housed with the completed book, that I am able to pass on so much information about this latest binding of mine.

The image above shows the binding made by Paul Bonet between 1963-64, sold by Christie’s in Paris on April 29, 2004 for 350,000 Euros. Sonia and Blaise had planned on making 150 copies however this was not completed.

“Was the primary reason for the incomplete edition the excessive length of time it might take to complete the pochoir process, assuming that the pochoir was the final procedure before binding? Did World War I intervene? Were there exhibits of the book, any reviews, any publicity at all? Were the sales disappointing? Did they run out of money?”

The actual number remains unknown, 74 have been identified but the list of these has never been published.

“The edition numbering system Blaise Cendrars used is somewhat random, indicating that the edition numbers were not written on the copies when they were first made. For example, there are two copies numbered 47, two numbered 111, and two numbered 139. Many copies do not have an edition number. There is a copy numbered 1 and one numbered 150.”

The La Prose of 1913 was printed on three materials: vellum, Japon and simile Japon, they stuck to the typical formula of publishing a deluxe edition and regular edition. Japon in one of many Japanese papers sold by the Japan Paper Company; simili Japon is made with Western fibres, also sold by the Japan Paper Company. The Paul Bonet binding is one of the vellum editions.

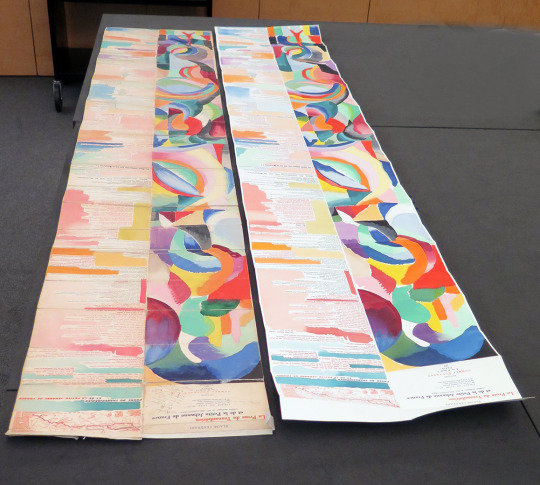

The below image shows Kitty’s recreation (right) alongside an original copy at The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, CA (left). This is #124, glued and folded into 21 panels, inscribed to Archipenko, the vellum cover is not attached.

“The book itself is captivating with its colorful and painterly pochoir (French-style stencil), so unlike stenciled copies of artwork at the time. The colors seep from the painted side into the poem on the other side.”

Kitty wanted to recreate the pochoir methods as closely as possible to the original using pommes (short, wide brushes) and metal stencil plates. Pochoir is a refined stencil-based technique employed to create prints or to add colour to pre-existing prints. It was most popular from the late 19th century through the 1930's with its center of activity in Paris. Numerous stencils were designed as a means of reproducing an image. (Photo courtesy of Kitty Maryatt)

My copy was one of two that Neale Albert (New York) had underwritten and commissioned. When I received my copy of the sheets in the post (#58 0f 150) they came with three different instruction sheets of how the pages could be folded - it was rather daunting!

The long vertical format of the book was an unprecedented choice for a book of the period:

“The Trans-Siberian Railroad was begun in 1890 when Blaise Cendrars was only three years old, but it was highlighted at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris that he attended with his family. The entire series of railroad lines weren't actually completed until three years after La Prose du Transsbérien was published. In the book, Blaise included a map of the journey from Moscow to Vlasivostok, which gives us a clue as to the distinctive folding scheme of the book. I've found tourist maps of Paris for the period similarly folded, in half first, and then in accordion – folded flat and glued to the cover. In the case of La Prose, as you open the book, you can't actually see anything in the book, neither the text nor the imagery, until the book is completely unfolded.”

It was up to me to choose which format I wished to use having been instructed that there was no set way of binding the book, so total creative freedom! Along with the written instructions, Kitty also sent all binders images of the folding and gluing process - crucial information to have before proceeding. There were three ways of folding the concertina, either like the original (left hand format), long and thin like the Paul Bonet binding (middle format) or double width (right hand format). (Photo courtesy of Kitty Maryatt)

The 1913 edition book covers were painted in oils by Sonia Delaunay, some covers had a snap, which made the book resemble a purse. Kitty’s version of La Prose is bound with vellum covers however she used acrylic paint to decorate the cover as she found that the oils yellowed the vellum. The book is housed in an acrylic slipcase and is pictured below. (Photo courtesy of Kitty Maryatt)