Text

[Week 10] The Internet: A Place for Memes… and Misogyny? Welcome to the Dark Side of Social Media

Social media – a magical place where you can watch endless cat videos, argue with strangers about Hawaii pizza, and share your life through perfectly filtered brunch photos. Sounds wholesome, right? But don’t be fooled. Beneath the surface lies something far darker. Welcome to online harassment: toxic, ugly, and way too real when a single post can turn you into a target for hundreds of attacking comments.

What is Online Harassment?

Online harassment is the digital version of someone being awful—threats, creepy comments, and offensive behavior aimed at others through the internet (Jones et al., 2013, p. 54).

Online harassment comes in all kinds of nasty forms. Here are some of the most common ones:

Trolling: Dropping nasty comments for the lolz.

Doxxing: Leaking your private info, like your home address.

Cyberstalking: The “Why are you in my inbox at 3 a.m. for the 7th time?” vibe.

Image-based abuse: Think revenge porn and non-consensual photo leaks.

Online harassment is not something that just popped up recently. It has been way back in the ‘90s with early chatrooms and forums (Citron, 2014, p. 3). Today, it is everywhere. A recent study found that 31% of Americans have experienced some form of online abuse, and out of those people, 75% said it happened on social media (Vogels, 2021).

So, instead of being the fun, friendly space it was meant to be, social media has unfortunately become a place where harassment often thrives.

Online Harassment is even gendered???

Of course, online harassment is bad for everyone, but it does not play fair. It hits differently depending on your gender, and (spoiler alert) women often get the worst of it.

Men typically face harassment based on their opinions. Maybe they got into a heated political debate or posted a controversial meme. Since men tend to share their opinions more publicly, it makes sense that harassment targets their attitudes and arguments (Vogels, 2021).

But for women? It is a whole different story. Women are harassed for simply existing online. Post a selfie? Someone might criticize your looks. Share an opinion? You could be called “emotional” or worse. Wear something even slightly revealing? Cue the flood of creepy comments and they are often hypersexualized (Nadim & Fladmoe, 2021).

Significantly, it is even worse for women of color and queer women, who face higher levels of abuse (Marwick & Caplan, 2018a).

So why?

The internet did not invent misogyny, it just gave it Wi-Fi. Traditional social norms and structures have been telling women to stay quiet, look pretty, and not take up space for centuries (Haslop et al., 2021). Now, instead of locking women out of boardrooms, they are trying to shove them off Twitter – a digital reflection of the same old power dynamics.

The #MeToo Effect: Empowering Women… and Empowering Trolls?

This is where things get complicated. When women started pushing back, demanding respect, challenging sexism, and calling out harassment – change began to stir. One of the biggest game-changers is #MeToo. It was a straight-up digital revolution, flipping the script on silence. Women finally had the mic to say “Enough!”, shining a giant spotlight on sexual harassment and collectively empowering survivors to share their stories (Moitra et al., 2021)

I remember scrolling through those posts, feeling hyped—like, finally, we’re loud!

However, that’s only half the story! #MeToo did not just spark empowerment, it also triggered fierce polarization in how men reacted. Some men saw the movement as a feminist tool designed to turn them into victims of false accusations (Maricourt & Burrell, 2022).

In response, they created online spaces that amplified anti-feminist backlash, better known as the “manosphere”—a toxic echo chamber filled with anger, misogyny, and rising waves of harassment aimed at silencing women (Marwick & Caplan, 2018b).

Another case is when an Indian artist sued an Instagram account after being named in #MeToo, turning her into the target of an online troll-fest (Moitra et al., 2021, p. 10). Though influenced by India’s cultural context, it reflected a broader pattern: #MeToo’s rise fueled male backlash, escalating online harassment and hostility toward women’s voices.

How government and the platform itself react?

Governments and social media platforms have rolled out policies (banning hate speech, adding reporting tools) to curb online harassment. On paper, it sounds promising. In practice? Not so much. Specifically, research has spotted Twitter’s inconsistent application of its policies when it fails to protect women from violence and abuse, leaving them to fend for themselves (International, 2018).

Look at Chrissy Teigen – she quit Twitter in 2021 after relentless trolling, saying it ‘no longer serves me as positively’ (ABC News, 2021). Even with Twitter reaching out, she was still drowning. That is the gap: rules exist, but they do not save you.

So, what is the solution? Real change will require a combination of stronger enforcement and grassroots action. That means holding platforms accountable, but also stepping up as digital citizens—calling out toxic behavior, amplifying positive voices, and supporting those targeted by hate. Fileborn & Loney-Howes (2019)argue that collective action can reshape online norms and spark broader social transformation.

✨ Together, we can flip the script, making a safer online world for everyone.

References

ABC News. (2021). Chrissy Teigen on why she deleted her Twitter account: “This no longer serves me as positively as it serves me negatively.” ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/GMA/Culture/chrissy-teigen-deleted-twitter-account-longer-serves-positively/story?id=76674746

Citron, D. K. (2014). Hate crimes in cyberspace. Harvard Univ. Press.

Fileborn, B., & Loney-Howes, R. (Eds.). (2019). #MeToo and the Politics of Social Change. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15213-0

Haslop, C., O’Rourke, F., & Southern, R. (2021). #NoSnowflakes: The toleration of harassment and an emergent gender-related digital divide, in a UK student online culture. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(5), 1418–1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856521989270

International, A. (2018). Toxic Twitter: Violence and abuse against women online.

Jones, L. M., Mitchell, K. J., & Finkelhor, D. (2013). Online harassment in context: Trends from three youth internet safety surveys (2000, 2005, 2010). Psychology of Violence, 3(1), 53.

Maricourt, C. D., & Burrell, S. R. (2022). #MeToo or #MenToo? Expressions of Backlash and Masculinity Politics in the #MeToo Era. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 30(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/10608265211035794

Marwick, A. E., & Caplan, R. (2018a). Drinking male tears: Language, the manosphere, and networked harassment. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 543–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1450568

Marwick, A. E., & Caplan, R. (2018b). Drinking male tears: Language, the manosphere, and networked harassment. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 543–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1450568

Moitra, A., Ahmed, S. I., & Chandra, P. (2021). Parsing the “Me” in #MeToo: Sexual Harassment, Social Media, and Justice Infrastructures. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449185

Nadim, M., & Fladmoe, A. (2021). Silencing Women? Gender and Online Harassment. Social Science Computer Review, 39(2), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439319865518

Vogels, E. A. (2021, January 13). The State of Online Harassment. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/

0 notes

Text

[Week 9] Pixels, Chaos, and Indie Dreams: Unpacking Melbourne’s Gaming Culture

Gaming – where you can plant cute crops, fight giant monsters, or scream at your screen after losing to some random kid on Call of Duty. Sounds like all fun and games, right? Well, there is actually a lot more going on behind the scenes. Gaming communities are full of history, culture, and all kinds of chaotic vibes. And Melbourne’s indie game scene? It is basically the cool underground party of the gaming world where there are no big studios – just bedroom creators making weird, artsy, glitchy games. Let’s dive in and see how this wild scene grew from zero to something way bigger than just pixels and controllers.

Histories & Cultures: Where Did It All Begin?

I used to think gaming history was all about things like Mario and Call of Duty—big names, big budgets, with big corps behind them. However, Keogh (2020) presents a different narrative: in Melbourne, indie games form a cultural scene more than a structured industry, due to the absence of AAA studios. This gap fostered a space where creativity and community took root over profit, with diverse groups like artists and students shaping the scene. It is a story of everyday people building a vibrant indie world, not just blockbuster giants.

Juul (2012) calls this shift a “casual revolution”—a moment when cheaper tools made it possible for just about anyone to create games. Suddenly, game-making was not limited to industry professionals—it was open to bedroom coders, modders, and small teams with big dreams

Does Money Kill the Indie Vibe?

Here is the catch: once the money rolls in, is it still indie? Or just a smaller version of AAA?

Actually, financial success does not automatically strip a game of its indie status—at least, not in theory. Numerous research leans hard on origins and processes. Take Minecraft—Mojang’s tiny team built it, and then it exploded into billions, but it is still called indie because it started scrappy and stayed true to Notch’s vision (Wolf, 2015).

Clarke & Wang (2020) make a solid point – indie is not black and white, but a spectrum. Games like Hollow Knight and Hades got extra funding later, but they kept their creative independence, small teams, and experimental vibe.

Therefore, what truly sets indie games apart is not just their budget but their heart. Passion, risk-taking, and freedom from corporate control are what keep indie games special. As long as creators hold onto those values, even when success comes knocking, they can still carry the indie spirit.

The Role of Streaming Platforms: Visibility vs. Constraints

Streaming platforms like Twitch and YouTube have become game-changers for indie developers, acting as “discovery engines” with the potential to transform a little-known game into an overnight sensation (Taylor, 2019).

Among Us is one of the clearest examples of this power. Initially overlooked, the game exploded in popularity after streamers embraced its chaotic, social gameplay (Fenlon, 2020).

But there is a harsh truth: Twitch loves noise and chaos. Games like Fall Guys, with their wild, fast-paced action, totally thrive. But slow, story-driven indie games barely get noticed. Why? Because they do not deliver those big, over-the-top moments that streamers and their audiences crave.

Parker & Perks (2021) also found that developers often complain about this: narrative games might get lots of views on Twitch, but they do not always translate into sales. Once audiences watch the full story unfold, they do not feel the need to buy the game themselves

For many indie devs, this creates an unpredictable gamble. In Canada’s indie scene, developers said that they feel stuck in a cycle of guesswork, with no clear formula for success on streaming platforms – just guessing and hoping for the best (Parker & Perks, 2021, p. 1744).

Ultimately, it makes me wonder: in this chaotic, streamer-driven gaming landscape, how can we, as players and fans, better support the games that speak to our hearts, not just our hype meters? Maybe it starts with a simple choice—buying that slow, story-driven indie game instead of just watching it unfold on Twitch. Because if we want soulful games to thrive, we have to show up for them.

References

Clarke, M. J., & Wang, C. (2020). Indie games in the digital age. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=8cTVDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR3&dq=Indie+Games+in+the+Digital+Age&ots=MMlb9_NMK2&sig=J0Xrxz3XR_ohkMbxO8qAoUO2Ax4

Fenlon, W. (2020). How Among Us became so wildly popular. PC Gamer.

Juul, J. (2012). A casual revolution: Reinventing video games and their players. MIT press. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=r4vRa7MGbYIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=A+Casual+Revolution:+Reinventing+Video+Games+and+Their+Players&ots=7yYL5zlwp3&sig=sNV3yEboIubXJ0SH7w9gCsuw-Lc

Keogh, B. (2020). 13 The Melbourne Indie Game Scenes. Independent Videogames: Cultures, Networks, Techniques and Politics, 209–222.

Parker, F., & Perks, M. E. (2021). Streaming ambivalence: Livestreaming and indie game development. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(6), 1735–1752. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211027809

Taylor, T. L. (2019). Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691184975

Wolf, M. J. (2015). Video games around the world. MIT Press Cambridge, MA. https://celt.cuw.edu/wp-content/uploads/VGAtW-proposal.pdf

0 notes

Text

[Week 8] Snap, Filter, Repeat: Are We Addicted to Digital Perfection?

Take a selfie, throw on a filter, and boom – you look like a superstar! Well, until the Wi-Fi drops. Yes, AR filters feel like social media’s magic wand, but are we just playing dress-up, chasing a perfect face that does not even exist?

The growth of AR filters

Augmented Reality (AR) filters are interactive tools that let you change how you look or what’s around you (Miller, 2024, p. 1). In simple terms, they allow social media users to adjust their appearance (like smoothing their skin) by adding digital effects that move with their face.

They started way back in the 1960s but hit the mainstream in 2015 with Snapchat, then Instagram (a Meta app) took them to the next level in 2017, now with over 2 million effects (Constine, 2017). Even I still remember how everyone, including myself, was so obsessed with the Snapchat puppy filter back then!

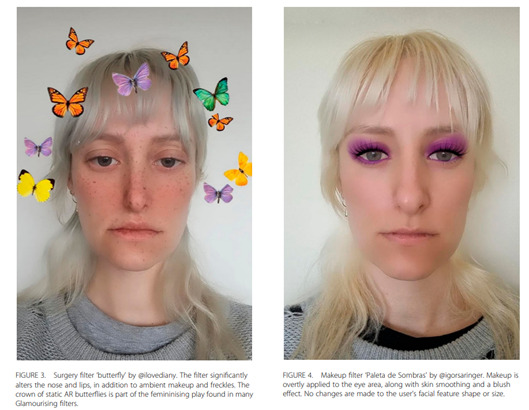

Types of AR Filters:

Glamourising Types: These enhance your looks, like smoothing skin or adding makeup. Some even mimic plastic surgery effects.

Entertaining Types: Think silly and playful ones, like the famous Snapchat dog filter.

Aestheticising Types: These change the mood of your photos, like adjusting colors, lighting, or adding vintage effects, taking them to a more photographic level.

And the hype? It is backed by numbers. Around 46% of Instagram’s 1.28–2 billion users have tried a filter, and every month, 700 million Meta users dive into AR (Cook, 2021; Dixon, 2024; Ryan-Mosleyarchive, 2021). Filters are not just a trend, they have become a core part of the digital world. But why are we so addicted to them?

What’s good about AR filters?

AR filters are a space for creativity and self-exploration, not just for beauty but for discovering new identities. They help users break free from stereotypes and barriers, allowing for more open self-expression.

For example, in a study by Ambika et al. (2023, p. 22), a student named Avishi shared how she used AR apps to try on blue and pink contact lenses. It made her question cultural norms about which colors suited her skin tone, something she had never considered before.

Similarly, Goetz (2021) found that Snapchat’s My Twin filter gave trans and non-binary users a safe way to experiment with gender traits. One user felt “affirmed” seeing a masculinized version of themselves resembling a male relative, making masculinity feel more “achievable” (Goetz, 2021, p. 9).

Research shows that teens use AR filters to connect with friends through playful interactions, like sending DMs to share laughs, chat, and create memes (Szambolics et al., 2023, p. 133). Beyond social bonding, these filters also boost mood, acting as a “cure for boredom” and a fun source of entertainment.

The Filter Trap

Beauty filters may seem harmless, but they promote a narrow, unrealistic standard—big eyes, white skin, sharp nose—erasing individuality (Alsaggaf, 2021). This has real consequences when people seeking plastic surgery to look like their filtered selves, struggling to match their online image. Some even developed “Snapchat dysmorphia,” feeling dissatisfied with their real appearance after years of digital editing (Hunt, 2019).

Filters also distort our perception of reality. The more we edit, the harder it becomes to recognize what’s “real,” leaving us constantly scrutinizing our own faces. This can lead to lower self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, and anxiety (Bakker, 2022). In the end, filters do more than change photos, they reshape how we see ourselves, often at the cost of our self-worth.

The Future of Filters

The future of filters is racing toward us, and it is more extreme than you think. In 2019, Alipay shocked users by adding beauty filters to face-scan payments, boosting usage by over 100%, and 123% among women (Bing, 2019). Now, imagine a world where your Zoom calls, online shopping, or even bank logins automatically "perfect" your face.

But is this really "convenience"? I don’t think so. Peng (2020) argues it is a form of control. Alipay’s filters embed beauty standards shaped by the male gaze, turning routine actions into silent beauty tests. If corporations and governments take this further, we might not even notice we are trapped in a polished, filtered cage.

References

Alsaggaf, R. M. (2021). The impact of snapchat beautifying filters on beauty standards and self-image: A self-discrepancy approach. The European Conference on Arts and Humanities. http://papers.iafor.org/wp-content/uploads/papers/ecah2021/ECAH2021_60204.pdf

Ambika, A., Belk, R., Jain, V., & Krishna, R. (2023). The road to learning “who am I” is digitized: A study on consumer self‐discovery through augmented reality tools. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 22(5), 1112–1127. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.2185

Bakker, M. (2022). # nofilter How beauty filters affect the internalization of beauty ideals [Master’s Thesis]. https://studenttheses.uu.nl/handle/20.500.12932/41835

Bing, L. (2019). The Beauty Filters Make Using Alipay Face-Scan Payments Can Beautify Your Face: The Number of Users Increased 100 per Cent [支付宝刷脸可美颜用户增长100%]. https://news.qq.com/?no-redirect=1

Constine, J. (2017). Instagram launches selfie filters, copying the last big Snapchat feature. https://techcrunch.com/2017/05/16/instagram-face-filters/

Cook, C. (2021). Discussing the Future of Spark AR. https://www.mbhumans.com/post/discussing-the-future-of-spark-ar

Dixon, S. J. (2024). Instagram users worldwide 2025. https://www.statista.com/statistics/183585/instagram-number-of-global-users/

Goetz, T. (2021). Swapping gender is a snap (chat): Limitations of (trans) gendered legibility within binary digital and human filters. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 7(2). https://catalystjournal.org/index.php/catalyst/article/view/34839

Hunt, E. (2019, January 23). Faking it: How selfie dysmorphia is driving people to seek surgery. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/jan/23/faking-it-how-selfie-dysmorphia-is-driving-people-to-seek-surgery

Miller, L. A. (2024). Preserving the ephemeral: A visual typology of augmented reality filters on Instagram. Visual Studies, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2024.2341296

Peng, A. Y. (2020). Alipay adds “beauty filters” to face-scan payments: A form of patriarchal control over women’s bodies. Feminist Media Studies, 20(4), 582–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1750779

Ryan-Mosleyarchive, T. (2021). Beauty filters are changing the way young girls see themselves. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/04/02/1021635/beauty-filters-young-girls-augmented-reality-social-media/

Szambolics, J., Malos, S., & Balaban, D. C. (2023). Adolescents’ augmented reality filter usage on social media, developmental process, and well-being. Media and Communication, 11(4), 129–139.

0 notes

Text

[Week 7] Hot or Harmful? The Social Media Beauty Script

Ever scrolled through Instagram and felt like everyone has the same face? That sculpted jawline, flawless skin, and perfectly symmetrical features? Yeah, welcome to the era of aesthetic templates—where beauty is less about individuality and more about fitting a mold. Social media hands us a ‘beauty script,’ and we are all racing to fit the part!

Where Did Aesthetic Templates Come From?

It all kicked off with microcelebrities—social media influencers who are not mega-famous like movie stars or singers but regular people like us, just with “a ton of followers.” They wrote this script, like Senft (2008, p. 15) notes with camgirls when they carefully select angles, lighting, and style to appear more attractive. Today, it is flawless skin and sharp features, all polished with filters.

Even the app favors this look when the algorithm does not care about what is real, it simply boosts whatever fits the ideal of “light skin & slim waists.” And those who do not fit in? They get shadowbanned. This happens because algorithms reflect the “worldview” of their creators, who often come from dominant social groups, reinforcing mainstream American cultural norms and biases (Duffy & Meisner, 2023, p. 294).

Selling Health, But at What Cost?

The story gets trickier when big celebs jump in, especially with stuff like health campaigns. Picture a star sharing fitness or self-love posts, all perfect—no sweat, no flaws. It is supposed to inspire, but research shows these polished images often make people have body dissatisfaction (Fardouly et al., 2015). Algorithms promote these posts because they get lots of attention, but the idea of “health” starts to feel less real.

Take #Fitspiration on Instagram, like The Rock, for example. His photos show perfect muscles, but never the sweat and hard work behind them. A study found that after just a few weeks of scrolling, people felt more anxious about their bodies (Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2018).

Beauty Script, Broken Minds

Scrolling those perfect pictures I catch myself thinking, “Why don’t I look like that?”. And of course, it is not just a passing thought. Research shows that constantly chasing these flawless images can have a serious impact on mental health. Particularly, it can even lead to Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), a condition where people become obsessed with minor or even nonexistent flaws in their appearance (Ryding & Kuss, 2020).

For those who do not fit the mold, such as Black or queer creators, the pressure is even greater. Social media platforms often hide their content if it does not match what is considered "attractive," making them feel the need to change who they are (Duffy & Meisner, 2023, p. 300). These beauty templates do not just raise the bar; they quietly convince people that they are not good enough unless they fake it.

So, is this beauty template too powerful to break? Only if we keep playing along

Every post, like, and comment fuels the algorithm, reinforcing beauty ideals we never meant to create (Gillespie, 2014). But if we built this system, we can rewrite it! Celebrate real beauty, uplift creators who break the mold, and challenge the filters shaping our feeds.

The system reflects us—so why not make it reflect something better?

🚨 Hot or Harmful? It Is Up to Us!

References

Duffy, B. E., & Meisner, C. (2023). Platform governance at the margins: Social media creators’ experiences with algorithmic (in)visibility. Media, Culture & Society, 45(2), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221111923

Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., & Halliwell, E. (2015). Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image, 13, 38–45.

Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, 167(2014), 167.

Ryding, F. C., & Kuss, D. J. (2020). The use of social networking sites, body image dissatisfaction, and body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review of psychological research. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(4), 412.

Senft, T. M. (2008). Camgirls: Celebrity and community in the age of social networks. Lang.

Tiggemann, M., & Zaccardo, M. (2018). ‘Strong is the new skinny’: A content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(8), 1003–1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316639436

1 note

·

View note

Text

[Week 6] Slow Fashion: An Ethical Solution or Just Consumerism in Disguise?

Fast fashion is the third biggest polluter in the world, accounting for 10% of global carbon emission — yep, you did not read that wrong. That is more than all international flights and maritime shipping combine (Uniform Market, 2024). And it does not stop there. Fast fashion also thrives on mass production, labor exploitation, and a never-ending cycle of waste. That is where Slow Fashion steps in, promising a more ethical and sustainable future. But is it really the hero we need, or just another expensive excuse to keep shopping guilt-free?

What is slow fashion?

Slow fashion is a movement that prioritizes sustainability, ethical production, and mindful consumption. Unlike what its name might suggest, slow fashion is not just simply about producing clothes at a slower pace, but rethinking the entire fashion system to minimize environmental and social harm (Fletcher, 2013).

Simply put, slow fashion is the opposite of fast fashion, including all of the following principles:

✅ Ensures fair wages and safe working conditions for garment workers (Fletcher, 2010).

✅ Uses eco-friendly fibers and utilizes technology to reduce waste and pollution (Pookulangara & Shephard, 2013, p. 201).

✅ Encourages consumers to prioritize quality over quantity, making mindful purchases that emphasize durability and long-term use rater than fleeting trends (Jung & Jin, 2016, p. 410).

Is it really 100% a perfect solution?

Of course, Slow Fashion sounds like a perfect solution for a better environment, it comes with its own issues

🚨 The Price Tag – Cotton costs 25% more than polyester, and opting for organic cotton (an eco-friendly choice) adds another 30% (Segran, 2024). Sustainability comes at a price, making slow fashion more of a privilege than an accessible solution for all.

🚨 Greenwashing – Big brands (H&M, Burberry) constantly release “sustainable collections” while still burning unsold stock and maintaining harmful production cycles (Koudelková & Hejlová, 2021, p. 36).

🚨 Still Consumption – Even if one buys less and invests in sustainable pieces designed to last longer, it is still consumption. Replacing fast fashion items with more sustainable alternatives does not eliminate consumption. Instead, it simply reshapes shopping behavior in a different direction while still being driven by the desire to buy (Koudelková & Hejlová, 2021).

Digital Citizenship and the Reinvention of Consumption

As digital citizens, we are constantly navigating an online ecosystem that shapes our consumption habits, even within the slow fashion movement.

Influencers who advocate for mindful shopping and "buying less" often contradict themselves by promoting affiliate links to expensive ethical brands, subtly reinforcing the urge to consume.

Social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram further fuel this cycle by pushing ever-evolving aesthetics—from capsule wardrobes to "old money style"—leading consumers to replace their existing clothes with "sustainable" alternatives. In the end, the pressure to curate the perfect ethical wardrobe can drive the same pattern of continuous shopping, just under a different name.

Matilda Djerf's Scandinavian minimalist aesthetic, for example, has driven followers to replace entire wardrobes in pursuit of a "clean girl" look—turning sustainability into ethically whitewashed consumption.

Slow fashion is undoubtedly a better alternative to fast fashion, but it is not the ultimate solution. True sustainability goes beyond just "buying less but better"—it requires a complete shift in how we engage with fashion with a mindset that values what we already own over the constant pursuit of the next best thing.

REFERENCES

Fletcher, K. (2010). Slow Fashion: An Invitation for Systems Change. Fashion Practice, 2(2), 259–265. https://doi.org/10.2752/175693810X12774625387594

Fletcher, K. (2013). Sustainable Fashion and Textiles (0 ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315857930

Jung, S., & Jin, B. (2016). From quantity to quality: Understanding slow fashion consumers for sustainability and consumer education. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(4), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12276

Koudelková, P., & Hejlová, D. P. D. (2021). “IS GREEN IN FASHION?” ANALYSING THE STRATEGIC COMMUNICATION OF FASHION BRANDS AND THE ATTITUDES OF GENERATION Z CONSUMERS TOWARDS ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES IN THE FASHION INDUSTRY. 11–13 OCTOBER 2021 Online Exclusive Event, 35.

Pookulangara, S., & Shephard, A. (2013). Slow fashion movement: Understanding consumer perceptions—An exploratory study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20(2), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.12.002

Segran, E. (2024, February 6). Why are sustainable clothes so expensive? Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/91020011/why-sustainable-clothes-are-so-much-more-expensive

Uniform Market. (2024, July 24). Fast Fashion Statistics 2025. https://www.uniformmarket.com/statistics/fast-fashion-statistics

0 notes

Text

The Real Power of Hashtags Activism: Attention, Action, or Just a Trend?

Digital activism has revolutionized social movements, turning hashtags into powerful tools for mobilization and collective action. A single post can spark global conversations. But let’s be real: when the buzz fades, does real change follow, or do we just end up scrolling past the next viral moment? Hashtags might stir the conversation, but are they sparking action, or just making noise? Let's unpack the digital hype.

Hashtags as the Heartbeat of Digital Movements

Digital activism harnesses the power of online networks to amplify voices, mobilize communities, and challenge societal norms. Instead of relying solely on traditional advocacy methods, activists now use digital platforms to drive conversations and spark action.

Within this landscape, hashtags have emerged as more than just metadata—they are rallying points that bring individuals together under a shared cause. This practice, known as hashtag activism, enables users to engage in political and social discourse by tagging their posts with a common label. Beyond simply organizing conversations, hashtags serve as catalysts for counter-publics, amplifying marginalized voices and challenging dominant narratives in mainstream discourse (Jackson et al., 2020; Jackson & Foucault Welles, 2015). Social media platforms further fuel this by making virality easier—through hashtag features, character limits, and algorithm-driven reach—allowing digital activism to break physical and social barriers (Leung & Lee, 2014; Penney & Dadas, 2014).

Some successful and most influential movements in the past decade have been fueled by hashtags such as #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter :

✅ #MeToo (2017) ignited a global movement, with over 19 million Twitter mentions averaging 55,319 per day (Anderson & Toor, 2018). Beyond its online virality, it also drove real-world impact, leading to workplace reforms and legal action against sexual harassment.

However, not all hashtag-driven campaigns achieve lasting change. #Kony2012 – once the fastest-growing viral campaign failed to create lasting change due to misinformation and a lack of sustained offline action. Despite widespread online support, the campaign struggled to translate digital momentum into meaningful real-world impact (Carroll, 2012).

This raises a critical question: Why do some hashtag movements create structural change while others fade into digital oblivion?

The Double-Edged Sword of Hashtag Activism

In the context of hashtag activism, the movement relies heavily on the collective voices of Twitter users, where posts are shared and amplified across a wide audience. This broad reach can lead to a disconnection between the different groups involved in the movement, as not all of them share the same perspective or values. When posts go viral, they can easily be seen by people outside the intended audience, including those with opposing views (Lampinen, 2020, p. 18).

Hashtag activism can be powerful in drawing global attention, but it can also unintentionally reinforce limiting ideas about those it tries to help (Dadas, 2017). A good example is the #BringBackOurGirls campaign, which, despite its wide reach, frames women as valuable only in relation to others, like family. As Loken (2014) points out, the phrase “our sisters and daughters deserve better” implies that missing girls matter only because they are someone’s daughters or sisters. This way of thinking risks reducing them to property, instead of seeing them as independent individuals who deserve freedom on their own.

Beyond the Hashtag: What Actually Makes Digital Activism Effective?

While hashtag activism has gained immense popularity, it is important to recognize that technology, including hashtags, is not a magical solution for social change. Haunss (2015) argues that technology is just one tool within a larger communication toolkit used by activists. Jenkins (2014) further supports the idea that instead of viewing hashtag activism as a complete revolution or a meaningless form of expression, we should consider it as a mechanism for participation in broader social movements.

To create lasting impact, movements must leverage both online momentum and real-world actions such as protests, lobbying, and legal advocacy. In this sense, digital activism becomes truly effective when it is paired with offline efforts that turn attention into tangible, systemic change.

REFERENCES:

Anderson, M., & Toor, S. (2018, October 11). How social media users have discussed sexual harassment since #MeToo went viral. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/10/11/how-social-media-users-have-discussed-sexual-harassment-since-metoo-went-viral/

Bestvater, S., Gelles-Watnick, R., Smith, A., Odabaş, M., & Anderson, M. (2023, June 29). 1. Ten years of #BlackLivesMatter on Twitter. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2023/06/29/ten-years-of-blacklivesmatter-on-twitter/

Carroll, R. (2012, April 21). Kony 2012 Cover the Night fails to move from the internet to the streets. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/apr/21/kony-2012-campaign-uganda-warlord

Dadas, C. (2017). Hashtag activism: The promise and risk of “attention.” Social Writing/Social Media: Publics, Presentations, Pedagogies, 24.

Haunss, S. (2015). Promise and practice in studies of social media and movements. Critical Perspectives on Social Media and Protest: Between Control and Emancipation, 13–31.

Jackson, S. J., Bailey, M., & Welles, B. F. (2020). # HashtagActivism: Networks of race and gender justice. Mit Press. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=zoHRDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=%23Hashtag+activism:+Networks+of+race+and+gender+justice&ots=JILqnBkdAq&sig=DDSo6QEqvw4dkV1CRUMYyOgPm3o

Jackson, S. J., & Foucault Welles, B. (2015). Hijacking# myNYPD: Social media dissent and networked counterpublics. Journal of Communication, 65(6), 932–952.

Jenkins, H. (2014). Rethinking ‘Rethinking Convergence/Culture.’ Cultural Studies, 28(2), 267–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2013.801579

Lampinen, A. (2020). Tweeting for change: How Twitter users practice hashtag activism through# BlackLivesMatter and# MeToo [Master’s Thesis, A. Lampinen]. https://oulurepo.oulu.fi/handle/10024/15514

Leung, D. K. K., & Lee, F. L. F. (2014). Cultivating an Active Online Counterpublic: Examining Usage and Political Impact of Internet Alternative Media. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19(3), 340–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161214530787

Loken, M. (2014). #BringBackOurGirls and the Invisibility of Imperialism. Feminist Media Studies, 14(6), 1100–1101. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2014.975442

Penney, J., & Dadas, C. (2014). (Re)Tweeting in the service of protest: Digital composition and circulation in the Occupy Wall Street movement. New Media & Society, 16(1), 74–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813479593

0 notes

Text

Reality TV: Truly Real or Just Scripted?

Reality TV presents itself as authentic, showcasing real people in unscripted situations. However, much of it is carefully crafted through staged scenarios and editing techniques. Today, we will explores how reality TV blurs the lines between fact and fiction—combining genuine emotions with manipulated narratives to create content that feels real, even when it is not.

Defining Reality TV

Reality TV is a type of entertainment that is considered "real" and "authentic" because it features real people in everyday situations, showing their genuine reactions and interactions without any acting (Trottier, 2006, p. 259).

This broad category includes a variety of programs, from globally popular shows like Keeping Up with the Kardashians (USA), which highlights the glamorous lives of a celebrity family, to lifestyle content covering topics such as healthcare, hairdressing, and even pets. In Vietnam, for example, Người Ấy Là Ai? focuses on relationships, while Anh Trai Say Hi centers around showcasing talent. Reality TV blends both informative and entertaining elements, combining the factual style of documentaries with the engaging appeal of dramatic storytelling (Wasko, 2005, p. 449).

The Rise of Reality TV

According to Roberts (2011, p. 1), non-scripted shows like Cops and The Real World actually existed before 2000 but remained on the fringes of mainstream television. That changed with the debut of Survivor on CBS in the summer of 2000, which marked the dawn of reality TV. Its finale drew over 50 million viewers, making it the second most-watched program of the year, just behind Super Bowl XXXIV (Roman, 2005).

Until now, Reality TV remains a global phenomenon, dominating streaming services with 29% and 28% audience preferences in Asia-Pacific and UCAN, respectively (Piana, 2024).

Producers are drawn to reality television because it is cost-effective, despite costing $100,000 to over $500,000 per episode, it remains significantly cheaper than many scripted shows (Palmer, 2023). But it is not just about saving money. Reality TV is popular for the ability to fulfill fundamental human desires, such as the need for self-importance, social connection, validation, freedom, security, and romance (Reiss & Wiltz, 2004). These shows feature real people experiencing genuine emotions in situations that are not scripted, making them feel authentic and easy for viewers to relate to. The combination of true feelings and dramatic moments captures the audience's attention in a way that scripted shows often cannot, which is why reality TV is popular across different cultures and generations.

Reality TV – how “real” is it, really?

While it promises unscripted drama and authentic moments, the reality is often far from genuine. Take shows like Keeping Up with the Kardashians or The Bachelor—do you think all that drama just happens naturally? In truth, producers often stage situations, coach participants on how to react, and even manipulate timelines to create juicy storylines. Techniques like “frankenbiting” splice together unrelated clips, making people appear to say things they never actually did (Edwards, 2013; Kultgen & Pace, 2022).

But here is the twist: knowing it is fake does not take away the fun – in fact, it makes it even more compelling! 🤩

In this way, viewers are not merely passive consumers; they actively analyze what is real and what is staged, turning the experience into a kind of puzzle (Jones, 2003). Even when viewers realize that some parts are scripted; the genuine emotions such as jealousy, heartbreak, and triumph still feel real and relatable. This reflects how audiences participate in constructing authenticity, balancing between what feels genuine and what is clearly performed (Rose & Wood, 2005, p. 284).

✔️ In the end, the appeal of reality television does not lie in being entirely real; it lies in creating moments authentic enough to spark curiosity and emotional connection.

Refereces:

Edwards, L. H. (2013). The triumph of reality TV: The revolution in American television. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=4IjDEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Techniques+like+%E2%80%9Cfrankenbiting%E2%80%9D+splice+together+unrelated+clips,+making+people+appear+to+say+things+they+never+actually+did.+&ots=5zhk06HiyO&sig=loSiNxGNkd_sLizFMA973SDoPpo

Jones, J. M. (2003). Show Your Real Face: A Fan Study of the UK Big Brother Transmissions (2000, 2001, 2002). Investigating the Boundaries between Notions of Consumers and Producers of Factual Television. New Media & Society, 5(3), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448030053006

Kultgen, C., & Pace, L. (2022). How to Win the Bachelor: The Secret to Finding Love and Fame on America’s Favorite Reality Show. Simon and Schuster. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=ZTVbEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP8&dq=Techniques+like+%E2%80%9Cfrankenbiting%E2%80%9D+splice+together+unrelated+clips,+making+people+appear+to+say+things+they+never+actually+did.+&ots=WAR3OW3je1&sig=pXufENzenXnTtDCI6ZIrPGIKcIM

Palmer, B. (2023). Why Networks Love Reality TV. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/financial-edge/0410/why-networks-love-reality-tv.aspx

Piana, F. (2024, September 23). Global Reality TV Trends. BB Media. https://bb-media.com/global-reality-tv-trends-international-preferences-production/

Reiss, S., & Wiltz, J. (2004). Why People Watch Reality TV. Media Psychology, 6(4), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0604_3

Roberts, J. (2011). Keeping It Real: A Historical Look at Reality TV. West Virginia University. https://search.proquest.com/openview/e853f070ea8c4b5a401887a733f6b42b/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

Roman, J. W. (2005). From daytime to primetime: The history of American television programs. Greenwood Press. https://doi.org/10.5040/9798400654404

Rose, R. L., & Wood, S. L. (2005). Paradox and the consumption of authenticity through reality television. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(2), 284.

Trottier, D. (2006). Watching yourself, watching others: Popular representations of panoptic surveillance in reality TV programs (p. 259). McFarland & Co. https://westminsterresearch.westminster.ac.uk/item/927wx/watching-yourself-watching-others-popular-representations-of-panoptic-surveillance-in-reality-tv-programs

Wasko, J. (Ed.). (2005). A Companion to Television (Vol. 24). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470997130

0 notes

Text

Freedom and Interaction: How Tumblr Outshines as a Public Sphere in the Digital World

In today’s fast-paced digital landscape, social media platforms have become essential spaces for public discourse and interaction. Among these platforms, Tumblr stands out for its unique ability to create a true public sphere—one where open dialogue thrives, free from the constraints of curated feeds and algorithm-driven content.

But what exactly defines a true public sphere?

According to Kruse et al. (2018), public sphere is a space where individuals engage in rational discourse, characterized by three key elements: unrestricted access to information, equal and protected participation, and the absence of institutional influence, particularly economic.

Equal and Protected Participation

Tumblr distinguishes itself by providing semi-anonymity, allowing users to create pseudonymous accounts and engage without the constraints of their real-world identities (Hillman et al., 2014). This is especially valuable for individuals from marginalized groups, such as LGBTQ+ communities, racial minorities, or those with dissenting opinions. Furthermore, Tumblr’s decentralized culture ensures no single voice dominates discussions, making it a more egalitarian platform for diverse participation.

On the other hand, Facebook, where real identities are required and social conformity often prevails, may discourage users from engaging in sensitive or controversial topics due to concerns about professional or social consequences. Moreover, the influence of Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs) and influencers on Facebook can steer discussions toward commercial or mainstream interests, as their opinions tend to carry more weight(Lin & Huang, 2024).

Absence of Institutional Influence

Tumblr's structure sets it apart as a public sphere largely free from institutional control, especially in political discourse. Platforms like Facebook use algorithms that prioritize content through paid promotions, steering political discussions toward commercial or governmental interests. In fact, there have been concerns about their impact on democratic institutions, particularly during the 2016 U.S. Election, where micro-targeted political ads influenced political opinions and conversations (Aierken, 2022; U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2020).

In contrast, Tumblr's emphasis on user-driven content creates an environment where grassroots content rises to the top. This assembled through algorithmic interventions and practices of sharing and appropriation, fosters a more democratic, unfiltered space (Pilipets & Paasonen, 2022).

Unlimited Access to Information

Tumblr’s open and decentralized structure fosters equitable access to information. Users freely share a diverse range of content—whether personal thoughts, art, social commentary, or political opinions—without being heavily filtered by algorithms or dictated by paid promotions. This organic approach ensures that users are not limited to narrowly tailored feeds or confined by algorithmic echo chambers. It encourages public conversations that are less controlled by corporate agendas, facilitating the freer exchange of ideas that Kruse deems essential for a true public sphere.

Refereces:

Aierken, A. (2022). Consumer Preferences for Attributes of Livestream Shopping: A Study of Generation Z [PhD Thesis, Concordia University]. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/990874/

Hillman, S., Procyk, J., & Neustaedter, C. (2014). Tumblr fandoms, community & culture. Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 288. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556420.2557634

Kruse, L. M., Norris, D. R., & Flinchum, J. R. (2018). Social Media as a Public Sphere? Politics on Social Media. The Sociological Quarterly, 59(1), 62–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380253.2017.1383143

Lin, Z. F., & Huang, K.-P. (2024). THE EFFECT OF KEY OPINION LEADERS’CHARACTERISTICS ON PURCHASE INTENTION: A STUDY OF TIKTOK LIVE COMMERCE IN CHINA. International Journal of Organizational Innovation, 17(1), 41.

Pilipets, E., & Paasonen, S. (2022). Nipples, memes, and algorithmic failure: NSFW critique of Tumblr censorship. New Media & Society, 24(6), 1468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820979280

U.S. Government Publishing Office. (2020). Selected Committee Report (pp. 116–290). https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/publications/report-select-committee-intelligence-united-states-senate-russian-active-measures

1 note

·

View note