Blog about Japanese language and history. I am currently studying for JLPT N3 (poorly).

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Somebody opened their umbrella at just the right time for this photo I took of Shinkyo Bridge, Nikko

402 notes

·

View notes

Text

But The Wind Rises declines to challenge mainstream Japanese society’s distortions and denials of its wartime atrocities. Worse, it echoes Japan’s morally dishonest stance that it was a victim, rather than a perpetrator, of a global war — a whitewashed version of history that the film now imports to every country where it plays. Consider the first scene. Jiro is a young boy; in his dreams, he heads for the skies in a wooden aircraft. A constellation of black dots appears above him, soon revealed to be a hangar’s worth of missiles and bombs. They dangle from a zeppelin embossed with the Iron Cross. The explosives fall on Jiro, reducing his plane to splinters. The rest of the film is suffused with this fear of German aggression, and it’s an ethically mendacious choice of a bogeyman on Miyazaki’s part. In The Wind Rises, the alliance between Germany and Japan — the original Axis of Evil — is conveniently forgotten, as scene after scene shows the Japanese bombarded by Teutonic suspicion, condescension, and hostility. Reframing the Japanese as the victims of Nazi racism deflects attention from the heinousness of the Japanese Imperial Army. But Miyazaki’s elevation of his own countrymen as morally loftier to the Nazis is only credible when the viewer forgets (or is unaware) that the Japanese military justified killing 30 million people across Asia with its own ideology of ethnic superiority. The Wind Rises continues this blame evasion throughout, evincing an ideal of pacifism while positioning Japan as the target of Chinese and American assault. We see Japanese planes downed by a Chinese foe in a mid-film reverie — a shockingly insensitive image given that Japan was invading China during this time, not the other way around. Later, an American bomber floats above a graveyard of burned-out aircraft over the defeated Japanese empire. In contrast, no Japanese pilot is ever seen shooting at an enemy, even though Jiro’s most famous invention, the Zero plane, was designed and used solely for military purposes. The consequences of his work — that is, corpses — are likewise absent. In the film, Jiro never expresses sympathy for the people his people killed. His grief is strictly reserved for the deaths of his planes. His preference to mourn his Zeros, rather than the planes’ victims, illustrates his soft-handed callousness. The bloodlessness of the film contributes to its whitewashing of an incredibly bloody history. No surprise, then, that The Wind Rises has already created an uproar among South Koreans (who haven't yet seen the film), arguably the biggest recipients of Japan’s 40-year colonial cruelty (1905-1945). The Wind Rises’ specious pose of self-victimization will and should disgust the living survivors and their descendants in the myriad other countries Japan invaded during World War II: China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia; the list goes on. It’s hard to believe that, were The Wind Rises set in an interwar Germany and focused on an idealistic dreamer who just wanted to design the world’s most beautiful U-boat and didn’t care a whit about the concentration camps, it would receive a similarly adoring reception here in the U.S. (At the time of writing, the film enjoys a 82 percent “fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes and has appeared on several best-of-year lists.) One would hope that critics who aren’t suffering from Japan’s culture of mass delusion about its war crimes would take into consideration the warped version of history Miyazaki has to accommodate and, to a large extent, perpetuates.

(2013)

407 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue depicting the first meeting between Toyotomi Hideyoshi and teenage Ishida Mitsunari. The traditional story is that Hideyoshi was on his way back to Nagahama castle from a hunt and stopped at a temple in the area to rest, and young a Mitsunari served him three cups of skillfully prepared tea. According to the (possibly apocryphal) story, Hideyoshi was so impressed by the boy that he decided to take him on as a page on the spot. The statue is located just outside of Nagahama Station.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you know that the english word “star” and the japanese word 星(ほし)don’t actually mean the same thing?

Language does not simply name pre-existing categories; categories do not exist in 'the world'

— Daniel Chandler, Semiotics for Beginners

I read this quote a few years ago, but I don’t think I truly understood it until one day, when I was looking at the wikipedia article for “star” and I thought to check the Japanese article, see if I could get some Japanese reading practice in. I was surprised to find that the article was not titled 「星」, but 「恒星」, a word I’d never seen before. I’d always learnt that 星 was the direct translation for “star” (I knew the japanese also contained meanings the english didn’t, like “dot” or “bullseye”, but I thought these were just auxiliary definitions in addition to the direct translation of “star” as in "a celestial body made of hydrogen and helium plasma").

To try and clear things up for myself, I searched japanese wikipedia for 星. It was a disambiguation page, with the main links pointing to the articles for 天体 (astronomical object) and スター(記号)(star symbol). There was no article just called 「星」.

It’s an easy difference to miss, because in everyday conversation, 星 and star are equivalent. They both describe the shining lights in the night sky. They both describe this symbol: ★. They even both describe those enormous celestial objects made of plasma.

But they are different - different enough to not share a wikipedia article. 星 is used to describe any kind of celestial body, especially if it appears shiny and bright in the night sky. “Star” can be used this way too (like Venus being called the “morning star”), but it’s generally considered inaccurate to use the word like this, whereas there is no such inaccuracy with 星. You can say “oh that’s not actually a star, it’s a planet”, but you CAN’T say 「実はそれは星ではなく惑星だよ」 (TL: that’s not actually a hoshi, it’s a planet). A planet IS a 星.

星 is a very common word, essentially equivalent to “star”, but its meaning is closer to “celestial body”. I haven’t looked into the etymology/history but it’s almost like both english and japanese started out with a simple, common word for the lights in the sky - star/星 , but as we found out more about what these lights actually were, english doubled down on using the common word for the specific scientific concept, while japanese kept the common word generic and instead came up with a new word for the more specific concept. If this is actually what happened, I’d guess that kanji probably had something to do with it - 星 as a component kanji exists inside the word for planet, 惑星, and in the word for comet, 彗星, and in the scientific word for “star”, 恒星, so it makes sense that it would indicate a more general concept when used standalone.

This discovery helped me understand that quote - categories don’t exist in the world, we are the ones who create them. I thought that the concept of “star” was something that would be consistent across all languages, but it’s not, because the concept of “star” is not pre-existing. Each language had to decide how to name each of those similar star-like concepts (the ★ symbol, hot balls of gas, twinkling lights in the sky, planets, comets, etc), and obviously not every language is going to group those concepts under the same words with the same nuance.

Knowing this, one might be tempted to say that 恒星(こうせい) is the direct translation for “star”. But this isn’t true either. In most of the contexts that the word “star” is used in english, the equivalent japanese will be simply 星. Despite the meanings not lining up exactly, 星 will still be the best translation for “star” most of the time. This is the art of translation - knowing when the particulars are less important than the vibe or feel of a word. For any word, there will never be an exact perfect translation with all the same nuances and meanings. Translation is about finding the best solution to an unsolvable problem. That's why I love it.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

yuri recs for @girlballs

That Time I Was Blackmailed By the Class's Green Tea Bitch

Oshikake Nyobo, Kodomo Tsuki!

Asumi-chan is Interested in Lesbian Brothels!

I Don't Know Which Is Love

Childhood Friend, Big Love

Ashita no Ashita

Android wa Keiken Ninzuu ni Hairimasu ka??

Shuu ni Ichido Classmate wo Kau Hanashi ~Futari no Jikan, Iiwake no Gozen'en~

Convenient Semi-Friend

Inkya Gyaru demo Ikigaritai!

Akumade Amai Watashi no Kanojo

A Yuri Manga That Starts With Getting Rejected in a Dream

Genkai OL to Joshi Daisei ga 〇〇 Suru Hanashi

Sugar Meets Girl!

Okiku-san wa Ichatsukitai

Mietemasu yo! Aizawa-san

The Main Duties of the Vice President

I Won't Let Mistress Suck My Blood

Akane Matsuri

Amasaya

Monthly in the Garden with My Landlord

Hogushite, Yui-san

Kiyota-san wa Yogosaretai!?

Geboku-san to Aruji-chan no Nichijou ~Aruji no Tame nara Nandemo shimasu~

Kage to Hana

The Dentist Won't Stop Teasing Me

Yuri Yuri Panic ~Toutosugiru Jian ga Hasseishiteimasu!~

I'm in Love with the Villainess

Tensei Oujo to Tensai Reijou no Mahou Kakumei

Alcohol and Ogre-girls

Shi ni Modori Oujo wa Ikinobiru Tameni Yuri Harem wo Tsukuru Koto ni Shita

Gakeppuchi Reijou wa Kurokishi-sama wo Horesasetai!

Gyaru Maid to Akuyaku Reijou ~Ojou-sama no Happy End shika Katan!~

Genkai OL-san wa Akuyaku Reijou-sama ni Tsukaetai

Real demo Shiawase ni Shite Kudasai ne?

Gal Oshi JK wa Gal ni Naritai

I Got a Girlfriend From a Shooting Star

Shino to Ren

Warning! Beware of the Dog

The Results of My Author/Classmate Discovering My Yuri Obsession

Warui ga Watashi wa Yuri ja nai

My Best Friend Who I Love Fell Completely in Love With My Vtuber Self

My Cute Little Kitten

Anmitsu Hoippu! Watashi ga Inakucha Dame na Kanojo no Hanashi

Gyaru to Ojousama

Peaceful Yuri Manga

Koharu to Minato: Watashi no Partner wa Onna no Ko

I'm the Only One for Miyaji Miyuki

not explicit yuri honorable mention

Witch Hat Atelier

From Bureaucrat to Villainess: Dad's Been Reincarnated!

30 Minute Sisters AROUND!

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

link: https://bsky.app/profile/brainvsbook.bsky.social/post/3llc72lyhu22j

google translate defaulting to chinese at first

okay but for those of us with interests in both the murderbot and the daomu biji fandoms this is kinda hilarious

(english-side-only really, i get that the kanji and hanzi are completely different)

our good (air)ship murderbot! thanks google

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

Got a question for all those who studied or know the history of the Japanese language, how come they've never discovered or added the f, v or l sounds? It's not like they're difficult sounds to produce, they are pretty basic so I don't really understand how, especially "la" is so easy to create as a sound.

173 notes

·

View notes

Note

I recently came across this old image of a oiran and i dont believe ive ever seen another oiran with a similar pony tail hairstyle before. I was wondering if you recognise it all?

Hello @fl3shisthelaw

Thank you for your ask. The term "Sagegami" is used as a catch all term for any Nihongami with a hanging ponytail. It can be read as "Hair hanging down the back" (下げ髪)

They are remnants of the Heian era when loose and long black hair was considered ideal in noble houses. Some distinct Nihongami have survived that are more distinct like the "Kottai Sagegami", prefered by Tayuu, the "Taregami" (垂れ髪) or Suberakashi (垂髪).

By the Edo period, Heian style hairstyles were already historic references so it harkened back to a golden age of noble culture. Any hairstyle with a long ponytail had this unique dignified air to it among a large collection of updos, which were very normal during the Edo period. Certainly something a Tayuu and later on an Oiran would have loved to do is imply any connection to noble status.

From what i have read, the Sagegami was one of more mature hairstyles, reserved for established Tayuu and Oiran.

Hope this helps. Thank you for dropping in.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr community for langblrs that like to read in Japanese

✨My tumblr community for reading in Japanese got approved ✨

I would like to use this community for the following:

Sharing recommendations: When you finish an interesting article, manga, novel, children's book, or blog post in Japanese, share it with the community and tell us if there's furigana, complex grammar or keigo to watch out for!

Asking for recommendations: Would you like to read more in Japanese but don't know where to start or which genre to try next? Ask the community for their recommendations for your specific level of Japanese and reading experience!

I'm looking forward to more recommendations and discussions of Japanese books form the perspectives of other learners! If you have any input for this community please let me know.

Let's read some books together! 📚🇯🇵

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

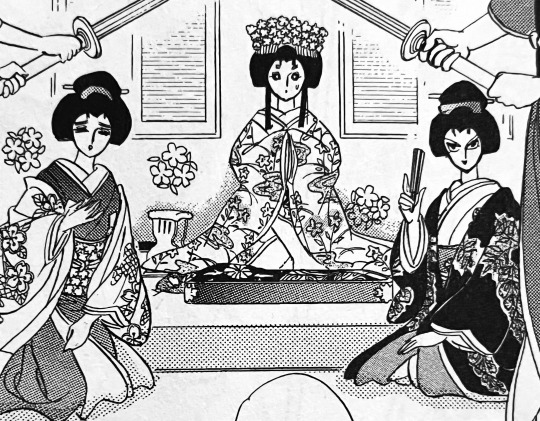

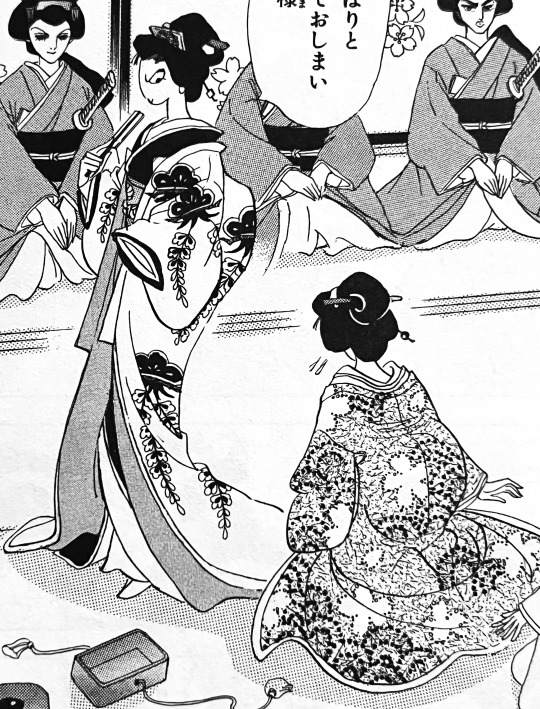

kihara Toshie — The Older Sister I Dislike

『わたしが嫌いなお姐様』 (Watashi ga Kirai na Oaneesama) — by 木原 敏江 Kihara Toshie

This work is part of a collection adapting three classic Kabuki plays into manga format. The specific story, Watashi ga Kirai na Oaneesama, is based on the play “Kagami Yama Kokyō Nishikie”.

🌸 Story Overview 🌸

This story is drawn and written beautifully by Toshie Kihara , emotionally layered story about a girl trapped in the shadow of her perfect, adored older sister figure. Set in the rigid world of historical Japan, it explores how admiration can twist into jealousy, and how the roles we’re forced to play can turn love into silent rivalry.

It’s a short but powerful manga, filled with quiet drama, longing glances, and the kind of poetic tension that makes you wonder who’s truly the villain—and who’s just hurting in silence.

My thoughts:

Reading Watashi ga Kirai na Oaneesama felt like holding a delicate porcelain cup filled with quiet emotions. It’s dramatic, yes—but also soft in the way it explores jealousy, admiration, and the ache of wanting to be seen. I expected a sharp rivalry, but what I got was something more tender: a story about misunderstood hearts and the silent ways people reach for each other, even through resentment.

It made me want to gently pat both characters on the head and say, “Hey… it’s okay to feel that way.” Wholesome in the most dramatic, kimono-wrapped kind of way. 🥀

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

春の丘 (Spring Hill) by Takabatake Kasho, 1929, originally published in the magazine 少女画報 (Shoujo Gahou).

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE LESBIAN ROBOTS ARE CANON LET'S FUCKING GOOOOOOO

29 notes

·

View notes