Text

youtube

How did Plutarch get the idea that Alexander slept with the Iliad under his pillow ... given how long the Iliad IS? Probably a bad case of ancient "telephone."

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

This is gonna sound VERY random, but do you know if Alexander loved or "stanned" any famous women during his time in the way that Gay men love their female Gay icons (think the way that Gay men love Judy Garland.) Like if Alexander were alive today I could honestly see him stanning Jennifer Coolidge lol.

Alexander was a fan of certain people—we know Thettalos was his favorite actor, for instance—BUT what the asker refers to is extremely time- and culture-locked.

In fact, it’s one of the primary reasons I resist using the term “gay” for Alexander. It brings to mind modern gay (male) subculture, which is highly anachronistic for Alexander…or the ancient world at all.

Why “Gay” Is a Problematic Term Applied to Antiquity

Alexander was not a gay man.

He was an ancient elite male who, like many ancient Greek men, appears to have swung both ways, but formed his primary emotional attachment to his childhood friend, Hephaistion.

I am not splitting hairs or being homophobic, or any of a dozen other possible complaints. The assertion that “Gay is gay is gay,” as a journalist long-ago insisted when she interviewed me in the wake of Oliver Stone’s Alexander, is dead-wrong.

That a man can be sexually attracted to other men (or a woman to other women)—primarily, sometimes, or only occasionally—seems to be as old as the hills. But how that’s understood … THAT is cultural. When it’s repressed, a counter-culture may grow up around it. Part of coming-out involves learning to participate—speak the language—of a new subculture. That may include a least pretending to certain expected tropes. A friend told me, some years ago, “I really hate Lady Gaga’s music, but if I say so, I might lose my gay card.” He was mostly joking, but also not.

A fairly specific gay male culture exists in the US, and Canada. This culture sometimes overlaps with gay male culture in other parts of Europe, including the UK, or other anglophone countries such as Australia and New Zealand. Some of that may overlap then with Spanish- or Portuguese-colonized South America, but by no means all. And it can be radically different from gay male culture in Asia, never mind Africa, or Arab-speaking countries. Etc.

We can’t point to any such gay subculture in ancient Greece because homoerotic behavior was widely accepted, at least among the upper classes. If there was any gay subculture, it was so closeted, we have no evidence for it. I’m inclined to think there was none precisely because it didn’t need to go in the closet in the first place. It was simply “elite” culture. Subculture signaling is created as a means to telegraph belonging to others “in the know” when it’s otherwise unsafe, or at least not fully acceptable, to be ____.

I hope this illustrates why the question doesn’t fit Alexander, but in a way that’s educational and enlarging, rather than a smack-down. The latter is not how I mean it, even while I do think it important to recognize cultural variance and why “gay” shouldn’t be used for the ancient world (even humorously, tbh). “Queer” is, I think, loose enough (however modern) to escape some of the assumptions. Yet the caution still remains.

If I can point to a bit of pop-culture to illustrate what I mean, consider the “Gay or European?” clip from Legally Blonde. It’s funny because it pokes fun at American assumptions. It’s also funny because, of course, the answer is “Both!” That doesn’t, however, negate the cultural lesson embedded.

youtube

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw someone asking here about Alexander grieving his father's death. That brought this question on my mind. Do you think Alexander openly grieved Philip's passing? What I can think of is, it was Hephaestion to whom he opened up. I can imagine him crying his heart out in Hephaestion's arms when they were alone together. I am not sure if he would even open up much to Olympias, though he was pretty close to his mother. What do you think?

For the ancient Greeks, Real Men Cry.

To a point.

Quite specific gender differences existed for male and female mourning in ancient Greece. If men swayed too close to women’s mourning, it was a problem. That was key to criticisms of Alexander’s mourning for Hephaistion. Essentially, he couldn’t control his grief, so he was “too girly.” But a failure to show any emotion—the proverbial “stiff upper lip”—would have been impious, not just “girly.”

Mourning was a religious expectation for any Greek. And Macedonian kings were duty-bound to bury their predecessor. Even Kassandros had to bury Arrhidaios and Alexander IV, no matter what he actually thought of them. At least in public, proper mourning behavior was expected.

That public mourning would involve the recitation of a goös, or formal elegy. Stylized mourning included loud calling out, a hand tearing at the hair, and possibly dirt on the head. Tears would be expected, as long as he wasn’t crying like a garden hose—or wailing “like a woman.” Note that, in the Iliad, Patroklos is made fun of by Achilles for “crying like a little girl” over the death of so many Greeks when the Trojans reached the Greek ships. There were limits, even as some expression of grief was not only allowed by expected.

As for Alexander’s mourning in private, I expect it was complicated, but I don’t think he would have kept it to himself except for Hephaistion. That’s not a very Greek view, imo. He’d have vacillated between anger at whoever killed Philip, and grief, and a need to learn what happened and punish the assassin. This was also a political act. Remember they did not know who did it, and it was entirely possible Alexander was the next target. (No, I don’t think Alexander had anything to do with his father’s death.) Even if he wasn’t, he’d still have been a target for his cousin Amyntas. Either he took the throne and lived (and Amyntas died), or Amyntas took the throne and Alexander died. That was the way of Macedonian inheritance with two viable Argead candidates, even with Alexander as designated heir. The next king waded to the throne through the blood of his competing relatives.

So a lot of pragmatic political matters would have impacted normal expressions of mourning. That’s independent of Alexander’s personal feelings about his father, which are difficult to know.

IMO, the popular image of Alexander and Philip at constant odds is exaggerated. In fact, if I were writing the novels today, I’d probably tone it down even more. But note that in DwtL, their relationship goes up and down. Sometimes they get along rather well; other times, not so much. Partly, that owes to Alexander being a teenager, when boys fight with their fathers anyway. But I think it also owed to the fact raising children was seen as a woman’s job and Philip was busy running a kingdom. He wasn’t present in Alexander’s life until he reached an age to be trained as an heir. Philip was that father with a high-powered occupation who sends his kid off to boarding school—literally, with Aristotle. That doesn’t mean he wasn’t interested, but he didn’t see himself as a father first. For one thing, he didn’t himself have exposure to good fathering. This is one of my novel’s themes, with the foiling between Philippos and Amyntor.

As for the real people, we’d need to know more about the state of their relationship when Philip was killed, and we just don’t have enough information because our sources for that period suck, honestly. Justin can’t at all be trusted, Plutarch has an agenda, and Diodoros is abbreviated to the point he stops making sense sometimes, but he might also be the least biased. As for Plutarch’s agenda, Philip is a barbarian king while Alexander is properly Hellenized due to his proper Greek education (via Aristotle), so he contrasts his father—until he falls under the sway of Corrupt Persian (Barbarian) Luxury and loses his Greek card. We must read all the Alexander-Philip conflict in Plutarch's Life in that fashion. Diodoros suggests things weren’t as dire as they appear in Plutarch, never mind Justin.

So I expect Alexander did mourn for his father, both in the ways expected of an Argead royal successor, but also as a son for his father. And not only in private with Hephaistion.

23 notes

·

View notes

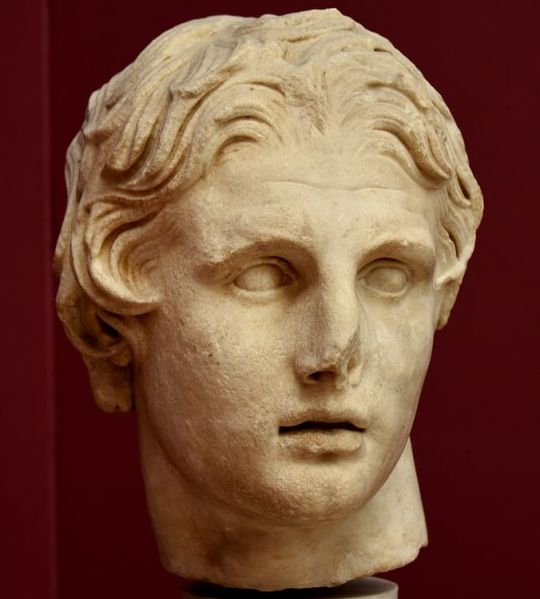

Photo

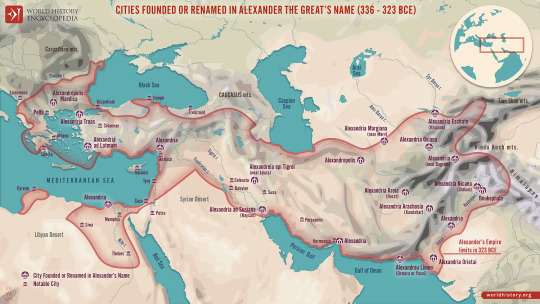

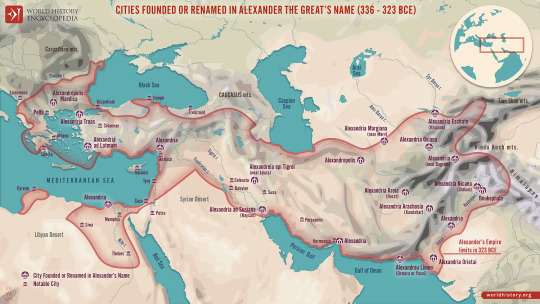

Alexander the Great founded, reorganized, or re-established several towns and cities across his empire and gave most of them the name of Alexandria (more than thirty by some accounts). He also dedicated one to his horse - Bucephalus, after the elderly animal died in the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BCE.

151 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alexander the Great founded, reorganized, or re-established several towns and cities across his empire and gave most of them the name of Alexandria (more than thirty by some accounts). He also dedicated one to his horse - Bucephalus, after the elderly animal died in the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BCE.

151 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ptolemaic Egypt

Ptolemaic Egypt existed between 323 and 30 BCE when Egypt was ruled by the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty. During the Ptolemaic period, Egyptian society changed as Greek immigrants introduced a new language, religious pantheon, and way of life to Egypt. The Ptolemaic capital Alexandria became the premier city of the Hellenistic world, known for its Great Library and the Pharos lighthouse.

From Persian Rule to Alexander

In 525 BCE, Egypt was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire, beginning a period of harsh foreign rule and cultural repression. Egypt briefly regained its independence from 404 BCE until 342 BCE before it was reconquered. Discontent with the Persian government resulted in the Egyptians welcoming Alexander the Great as a liberator when he invaded in 332 BCE. Alexander had already broken the Persian army at the Battle of Issus (333 BCE), and Mazakes, the satrap of Egypt, surrendered without a fight.

Alexander demonstrated a deep respect for Egyptian culture, choosing to be crowned pharaoh according to traditional custom. He offered sacrifices to the Egyptian gods in Heliopolis and Memphis and hosted Greek athletic games to celebrate his reign. Next, he traveled south to the Oracle of Amun, whom the Greeks equated with Zeus, in the Siwa Oasis. Alexander believed himself to be the son of Zeus, which the oracle seemingly confirmed for him. The idea had precedent in Egyptian royal ideology in which kings were considered living gods, the offspring of deities like Ra or Amun. It was an unusually grandiose claim for Greek rulers, but Alexander’s reputation was great enough for the Greeks to accept him as a demigod.

Alexander’s grand design will slowly have come to encompass the idea that all peoples were to be subjugated for the formation of a new world order; for this purpose, the Egyptian pharaonic system presented a very suitable ideology that was well established and has been accepted for millennia.

(Hölbl, 9)

In 331 BCE, Alexander visited the fishing village of Rhakotis where he planned the foundation of a new city, Alexandria. He intended for Alexandria to be the capital of his empire, a link between Egypt and the Mediterranean. Before leaving to continue his conquests, Alexander appointed two governors, Doloaspis and Peteisis, and named Cleomenes of Naukratis, a Greek Egyptian, as his satrap. He also left a small army to occupy and defend Egypt.

After the death of Alexander the Great in Babylon in 323 BCE, his general Ptolemy I became satrap of Egypt. He was nominally the servant of Alexander’s successors Philip Arrhidaeus and Alexander IV of Macedon, but in reality, he ruled on his own initiative. Ptolemy I quickly executed Cleomenes, whose exorbitant taxation was unpopular, and began establishing royal policies to modernize the country. By 310 BCE, the last of Alexander’s heirs had died, and during the Wars of the Diadochi, Alexander’s generals claimed pieces of his empire. Ptolemy I was crowned king of Egypt in 306 BCE, establishing the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Continue reading…

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just out. Yes, it's stupid-expensive, but perhaps you can get your local library to get a copy.

This is the second important collection on ATG out this year, and which I have a chapter in. I'm rather proud of my material in both the Cambridge Companion to Alexander the Great (which is fairly priced for an academic book of its size), but also (and maybe especially) this one.

My Cambridge chapters pull together some important recent work on Alexander's court and the conflicts among the Hetairoi and with the army. So if you were intrigued by my recent posts on the drama around Alexander, I talk about it in the Cambridge Companions, especially the second chapter (12: "Changes and Challenges at Alexander's Court"). It pulls together some divergent material that I think all bears on the other (especially the recent work on Archaic Macedonia), and I throw out some proposals/revisions of prior thought. But it's as much summarizing as original work.

My chapter in the Brill Companion to the Campaigns of Philip II and Alexander the Great is primarily original research. And a (I hope) super-duper useful table of ALL religious references in the 3 or 5 original sources, on both Philip and Alexander. That's not been done, to my knowledge, like, ever. Fredricksmeyer's dissertation in 1954? (unsure of date and too lazy to look it up, but the mid-50s) was the last really serious, extensive look at Alexander and religion that consolidated the sources. And he didn't provide tables.

So yeah, that's my BIG contribution to ATG research in the past decade, really. And it's SYNOPTIC, folks. What does that mean? I record where X event occurs in each of the 3 or 5 primarily sources for each king, with holes for who didn't record it. If you've ever seen a copy of the Synoptic Gospels, that was my model. This is SUPER useful because it lets you see who told what story, how different sources changed details, and what *sort* of religious action each event/reference was.

It's a long chapter, in part because of that table. It took a lot of work. But I really hope it proves a useful resource (beyond just my commentary on it) for future research on Alexander.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

give alexander the great one (1) monster energy drink and he would’ve conquered mars

93 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Hyphasis Mutiny

The so-called Hyphasis Mutiny was a conflict between Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) and his army following their victory at the river Hydaspes in 326 BCE. Alexander voiced plans for further conquests in the Indian subcontinent, however, when his men reached the river Hyphasis, there was an open revolt. The mutiny ended with Alexander giving in to his men’s wishes and turning back; he did not venture further into the Indian subcontinent as he intended. Over the years, historians have examined the importance of this moment of tension between a king and his army. This includes the issue of whether the term “mutiny” can truly apply to this incident.

The Indian Campaign

When Alexander marched across the Hindu Kush to India in 327 BC, the denizens of Bazira feared for their lives, fled to the Aornos Rock, reputed to be impregnable so that not even Heracles was able to capture it. Alexander had difficulty getting to the rock and started building a mound, then gained a foothold on a hill. When the Indians noticed the Macedonians closing in, they surrendered. Alexander placed a garrison on the abandoned portion of the Aornos Rock.

The city of Nysa asked Alexander to recognize their freedom and independence, which Alexander granted and made allies of them, acquiring 300 horsemen. He also had a base in Taxila, after promising to help Taxiles against his enemy, King Porus. Alexander met Porus at the Battle of Hydaspes in 326 BCE, which included war elephants. After the battle, Porus was allowed to continue ruling his kingdom and became an ally of Alexander, and Alexander continued to march further into India.

Continue reading…

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Hyphasis Mutiny

The so-called Hyphasis Mutiny was a conflict between Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) and his army following their victory at the river Hydaspes in 326 BCE. Alexander voiced plans for further conquests in the Indian subcontinent, however, when his men reached the river Hyphasis, there was an open revolt. The mutiny ended with Alexander giving in to his men’s wishes and turning back; he did not venture further into the Indian subcontinent as he intended. Over the years, historians have examined the importance of this moment of tension between a king and his army. This includes the issue of whether the term “mutiny” can truly apply to this incident.

The Indian Campaign

When Alexander marched across the Hindu Kush to India in 327 BC, the denizens of Bazira feared for their lives, fled to the Aornos Rock, reputed to be impregnable so that not even Heracles was able to capture it. Alexander had difficulty getting to the rock and started building a mound, then gained a foothold on a hill. When the Indians noticed the Macedonians closing in, they surrendered. Alexander placed a garrison on the abandoned portion of the Aornos Rock.

The city of Nysa asked Alexander to recognize their freedom and independence, which Alexander granted and made allies of them, acquiring 300 horsemen. He also had a base in Taxila, after promising to help Taxiles against his enemy, King Porus. Alexander met Porus at the Battle of Hydaspes in 326 BCE, which included war elephants. After the battle, Porus was allowed to continue ruling his kingdom and became an ally of Alexander, and Alexander continued to march further into India.

Continue reading…

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hephaestion

Hephaestion was a member of Alexander the Great’s personal bodyguard and the Macedonian king’s closest and lifelong friend and advisor. So much so, Hephaestion’s death would bring the young king to tears. From 334 to 323 BCE Alexander the Great conquered much of the known world. He led his army on a ten-year odyssey across Asia Minor and into Persia, Egypt and India. Eventually, after his defeat of Darius III, he became the self-proclaimed King of Asia. Of course, he could not have done this without the support of his loyal army and staff of skilled officers – Ptolemy I, Perdiccas, and Craterus, but above all others, Hephaestion.

Early Life

The son of Amyntas, Hephaestion was raised in the Macedonian capital of Pella and according to most sources born in 356 BCE, the same year as the king. Being from an aristocratic family, as were many of the staff officers who would follow Alexander into Asia, he became a student, alongside Alexander, of the philosopher Aristotle at Mieza, a city west of Pella. His intelligence impressed the Athenian academic, and, like the king, they would correspond with each other during the long Persian campaign.

Hephaestion was considered handsome by many, and Alexander’s father, Philip II of Macedon, regarded him as an excellent influence on his son. Shortly after Philip married Cleopatra, the future king became concerned about his position as successor. A disagreement erupted between Philip and Alexander, a dispute fueled by his friends. Because of this, many of Alexander’s friends were sent into exile; however, because of Philip’s respect for Hephaestion, he was spared this humiliation.

Continue reading…

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Hyphasis Mutiny

The so-called Hyphasis Mutiny was a conflict between Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) and his army following their victory at the river Hydaspes in 326 BCE. Alexander voiced plans for further conquests in the Indian subcontinent, however, when his men reached the river Hyphasis, there was an open revolt. The mutiny ended with Alexander giving in to his men’s wishes and turning back; he did not venture further into the Indian subcontinent as he intended. Over the years, historians have examined the importance of this moment of tension between a king and his army. This includes the issue of whether the term “mutiny” can truly apply to this incident.

The Indian Campaign

When Alexander marched across the Hindu Kush to India in 327 BC, the denizens of Bazira feared for their lives, fled to the Aornos Rock, reputed to be impregnable so that not even Heracles was able to capture it. Alexander had difficulty getting to the rock and started building a mound, then gained a foothold on a hill. When the Indians noticed the Macedonians closing in, they surrendered. Alexander placed a garrison on the abandoned portion of the Aornos Rock.

The city of Nysa asked Alexander to recognize their freedom and independence, which Alexander granted and made allies of them, acquiring 300 horsemen. He also had a base in Taxila, after promising to help Taxiles against his enemy, King Porus. Alexander met Porus at the Battle of Hydaspes in 326 BCE, which included war elephants. After the battle, Porus was allowed to continue ruling his kingdom and became an ally of Alexander, and Alexander continued to march further into India.

Continue reading…

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Antipater (Macedonian General)

Antipater (c. 399-319 BCE) was a Macedonian statesman and loyal lieutenant of both Alexander the Great and his father Philip II of Macedon. As a regent in Alexander’s absence, Antipater subdued rebellions and mollified uprisings, proving his unwavering loyalty for more than a decade. Unfortunately, a serious disagreement between the two led to a once trusted commander being implicated in the suspected poisoning of one of history’s greatest leaders.

Early Career

Antipater had always been considered a trustworthy commander, representing Philip at Athens in 346 BCE. Following the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE, he was entrusted with the task of accompanying the young Alexander in taking the ashes of fallen Athenians killed in battle to the city. After Philip’s assassination by the disgruntled Pausanias, a disagreement arose among the nobility as to who was the rightful heir to the throne of Macedon. At a meeting presided by Antipater, several nobles voiced support for Amyntas, the son of Philip’s brother Perdiccas. Some of these men disliked Alexander only because his mother was not a true Macedonian. However, Antipater and fellow commander Parmenio, who was in Asia Minor at the time, remained loyal to Alexander, so with the urging of his doting mother, Olympias, Alexander became king at the age of 20.

The first few years of his reign were not easy for the young king. Following his father’s death, Alexander found not only his ability but also the strength of Macedon’s control over Greece threatened. While the young king and his army traveled northward to secure Thrace in 335 BCE, Antipater remained in Macedon, serving as his deputy. While in Thrace, word of Alexander’s supposed death made its way to the Greek city of Thebes and they revolted. When they heard of the approaching the Macedonian army, they assumed, incorrectly, that it was under the command of Antipater. Wrong! It was Alexander, and the city would suffer. The rest of Greek city-states - except for Sparta - quickly realized the true strength of Alexander and submitted willingly to his leadership.

Continue reading…

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prosopography R Us! Fun with Hephaistion's allies and enemies at the court of Alexander.

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think that Alexander was truly liked by those around him, in a personal level? True friendship. Not really Hephaistion but also like Ptolemy, Seleucus, Roxanne, Arrhidaios, those who grew up with him or were his closest circle. Or was it all cynical politics?

Found it! That was weird. Appearing/disappearing asks?

Did the people around Alexander like him?

Did the people around Alexander like him? Hephaistion did. But the rest?

The asker refers to his personal circle, but I want to address this more broadly. I’ll return to his personal circle at the end.

First, we must beware of that pesky “shading” by later authors as part of their attempts to use Alexander’s career for commentary on their own time. They meant to show how success and power spoilt him and made him into a tyrant. That said, I believe he was well-liked overall. Yet things did change over time.

He began as king of a (relatively) small kingdom in northern Greece where all a Macedonian had to do before addressing him was to take off his hat—didn’t even use the title “King.” By his death, he’d taken over in a tradition that depicted rulers as “King of Kings” and “King of the Four Quarters” [e.g., the Whole World], even a god-king (Egypt). Going from (little) Macedonia to (enormous) Asia naturally cut down on his availability to soldiers and even his own Companions/Hetairoi—which pissed them off. Partly, it was simple logistics. He had too many responsibilities, and too many people wanted a piece of his time. Yet after Darius’s death in 330, he also added layers of court ceremonial to better align with ancient near eastern royal expectations and secure Persian respect.

That alienated his own people (maybe more than he expected). However exaggerated I believe the objections to his adoption of Persian custom, there’s little doubt it wasn’t well-received by traditionalists who preferred their kings approachable. Now, be aware: that approachability was more curated than our sources admit, as these sources inflated shifts to serve their own themes. Macedonian kings had bodyguards for a reason, and certain aspects of divine charisma were associated with their physical person (see below). The average citizen could NOT just wander up to one for a chat. Even so, elaborate Persian ceremonial was quite alien to Macedonia.

Nor was such ceremonial required of Macedonians in 330; our sources note that Alexander was essentially running two parallel courts with differing expectations. Nonetheless, the Macedonians took exception to the changes, offended to see “their” king “succumb” to foreign ways. He was getting uppity. They may also have feared it would trickle down to them eventually, even if it hadn’t yet.

Kleitos the Black’s exact words to Alexander in their infamous, alcohol-fueled spat is 99% invented. (Except maybe the line from Euripides; I’m least suspicious of that.) Some of it involved a play mocking officers who’d died recently at the Marakanda massacre as a means to absolve Alexander, who hadn’t been present, but whose failure to clarify the chain of command got them killed. I suspect that was a lot of it. But as with all “straw that broke the camel’s back” fights, it quickly escalated into a litany of complaints. Some of those were about the changes at the court. And Kleitos didn’t survive the encounter.

Alexander’s remorse appears to have been genuine. And the fact the army was ready to convict Kleitos of treason after-the-fact, said a lot about their empathy for the king. Nonetheless, after that, NOTHING was the same for his inner circle. In the right circumstance, he might kill you. And the army would absolve him of it.

Yet the army didn’t regard every negative act by Alexander as forgivable. They were not willing to overlook the murder of Parmenion. If they could understand/see themselves getting worked up enough to kill even a good friend when drunk, the cold, calculated removal of a potential (not even demonstrated) political threat was something else again. Especially a threat who’d served Alexander (and Philip) with such distinction.

E.g., nuance is required when assessing soldierly opinion.

A couple more things suggest Alexander was—overall—beloved:

1. At the battle of Granikos, he was elected the ancient equivalent of MVP; an award made by soldiers. He accepted, then never allowed his own name to be in the running again. Yet it was an award from the soldiers, and means he was respected not just as a leader, but as a fighter.

2. During both so-called “mutinies,” the soldiers didn’t want to kill him, they only wanted him to change his policies. If there’s some doubt the first actually occurred, the second at Opis certainly did. Yet when he showed the soldiers what it would mean to reject him (he replaced them), they came crying for his forgiveness. They didn’t say, “Good riddance” and head home.

3. On his deathbed, the Macedonian soldiers clamored so to see him that his top officers had to knock down a palace wall in order for them to parade through and say a final goodbye.

Now, that’s soldiers. What about his Companions/Hetairoi? At this high level, liking or disliking also involved personal advancement and family position—as the asker alluded to.

Those willing to “play ball” (so to speak)—go along with Alexander’s changes—had a whole new world opened. This wasn’t just his personal circle but included figures such as Krateros who understood what side his bread was buttered on. I’m not sure how much love was lost between him and Alexander, but they certainly respected each other. There were others who fell into this category, such as Koinos and Kleitos the White. Non-Macedonians/Greeks too, who may have seen him as a road to higher office than they’d held under Darius, or perhaps just to survival. Although I do think Poros and Alexander had a Moment; Poros remained loyal even after it served him to do so, despite his own son’s death at the Battle of Hydaspes. Something actually clicked with those two, I believe.

As for those who grew up with him—Hephaistion, Perdikkas, Leonnatos, Seleukos, Lysimakos … it seems they did like him, even if they didn’t always like each other. Seleukos was responsible for Perdikkas’s murder, in the Successor Wars later. There were others, but those names float to the top again and again. Similarly, although older, Harpalos, Ptolemy, Erigyios, and Laomedon all got themselves exiled for his sake. And Alexander never forgot it. The man who brought news to Alexander of Harpalos’s first flight (due to embezzling) was initially arrested for a false report. Alexander simply didn’t believe his friend had betrayed him.

And it wasn’t just those men. The tale of Alexander drinking a medical potion given him by his doctor Philip—despite a missive from Parmenion warning him about Philip—became famous as a tale of trust. And sure enough, the drought cured the king, so ATG’s trust was well-placed. A later story about Alexander locking up Lysimachos in a cage with a lion in punishment is almost certainly bogus (with overtones of Roman-era stuff). Other evidence suggests great affection for his men. That’s perhaps why Philotas’s failure to inform him about a conspiracy endangering his life came as such a blow.

One may wonder if some of those guys, like the talented—and older—Krateros, didn’t want to replace him as king? Certainly after his death, they did vie to be kings.* Periodically, I run across some misguided person arguing that Philotas and/or Parmenion wanted to take his place, hence the conspiracy. It’s even embedded in our ancient sources, which didn’t understand Macedonian kingship (were thinking on Roman models).

But those men couldn’t be kings. They weren’t Argeads, and it mattered. (Such supposition also assumes they were part of the real conspiracy, rather than Philotas simply being an arrogant dumbfuck who failed to report it.)

The Argeads had Royal Charisma. Charis is a gift from the gods: literally. It can be beauty and grace, sure, but at its base, it simply means “favor.” The difference between a king and a tyrant was that the former had charis by descent. The men who became tyrants (or tried and failed) all believed they had it too, but by their own demonstrated aretē and timē. That’s why they were never just popular Joe Blow off the street. They were Olympic victors, winning generals, etc. All were also aristocrats and fully intended to establish their own royal dynasties…but failed.

Until the Hellenistic Age. The Successors were just tyrants who made it work. Some (like Seleukos) even created mythological origins for themselves. Daniel Ogden has a good book on the creation of this myth: The Legend of Seleucus: Kingship, Narrative and Mythmaking in the Ancient World. If you’re curious about how all those things go into charis, I recommend it.

It’s not enough to be competent. One also needed the gods’ blessing. Charisma. That’s why Alexander’s officers might compete with and snipe at each other…but not with/at him.*

As for figures such as Roxane or Oxyathres (Darius’s brother who joined ATG’s court after Darius’s murder), it’s impossible to know what their opinion of him would have been. We have zero reliable evidence. It would seem Sisygambis (Darius’s mother) genuinely liked him. But again, this may have served later narratives, so I wouldn’t swear to it. She might have just made the best of a bad situation.

So! The final vote is that he seems to have been more popular/well-received than not … for a rather ruthless ancient world conqueror. Ha. I think that’s part of his eternal fascination. He’d be far less interesting if he’d simply been a monster.

Also, I forgot, but I did a separate post a while back on a related topic: Did Alexander's Companions Like Each Other

————————

* It took some years before the Successors started using the title “King” (Basileus). Antigonos Monophthalmos was the first, if I remember right, around the same time Alexander IV was murdered by Kassandros—and he didn’t claim the title himself. It was given him by Athens. Up to that point, they’d all simply called themselves “governors” and/or “regents.” Even if they might have been privately considering how to become kings in their own right, the charisma of Macedonian kingship belonged to the Argeads. Getting rid of Alexander IV (quietly), then Olympias’s murder of Philip III Arrhidaios and Hadea Eurydike left no Argeads. Then Alexander’s empire could become “spear won” territory.

37 notes

·

View notes