Life is beautiful... and life is complicated. I'm a pastor, wife, and mom to a two smart and funny daughters and a son who, through his life and death, taught us what courage really means. This is my life: full of laughter and tears, grace, and a whole lot of rubber ducks.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Patchwork Hope

“And having loved his own who were in the world,

Jesus loved them to the end.” – John 13:1

they say

that even the rich and famous are stuck at home

and the fashion designers have set aside their sequins and satins and silk

and instead they sew gowns and hats and masks for the heroes

who show up each day to fight the enemy we cannot see

and I sit

at my own little sewing machine

my crooked seams as far from couture as you can get

I sit

stitching masks

which I know aren’t enough

but they’re all I’ve got to give

I sit and I sew

and I pray

I pray for those who will wear these masks

I pray for the community outside my walls

I pray for healing and safety and strength

and I pray that one day

one day

these masks will be torn apart

every stitch ripped out

and these grim reminders of our frailty

will be reassembled into baby blankets

and teddy bears

and wedding quilts

and baptismal gowns

each one a patchwork of pain redeemed

and perseverance

a ragged reminder of darker times

and the promise of resurrection that kept us holding on

and maybe, God willing

one day I’ll cradle my grandbabies

swaddled in blankets

made from the fragmented pieces of masks once soaked with tears

now perfumed with the aroma of life made new

and one day the museums will advertise piles of elastic

and ribbons and ties ripped from those masks

now set aside

but which still stand as a reminder of the way we pulled together

a silent witness to all those stitches which hold us together

and bind us together

and how great we were

when we all came together

by staying apart

I sit and stitch

alone

and realize

we are not our own

and we have never been alone

and maybe I won’t see that day

but by God, someone will

so I sew and I sing

I stitch and I pray:

Bind us together, Lord

Bind us together

With cords that cannot be broken

Bind us together, Lord

Bind us together

Bind us together with love

--------------------------------------------------

(this poem is for my kids

who think my crooked seams are perfect

and whom I hope are learning more than sewing skills

when they look at me)

- Bri Desotell 3/25/2020

“Bind Us Together” words and music by Bob Gillman.

1 note

·

View note

Text

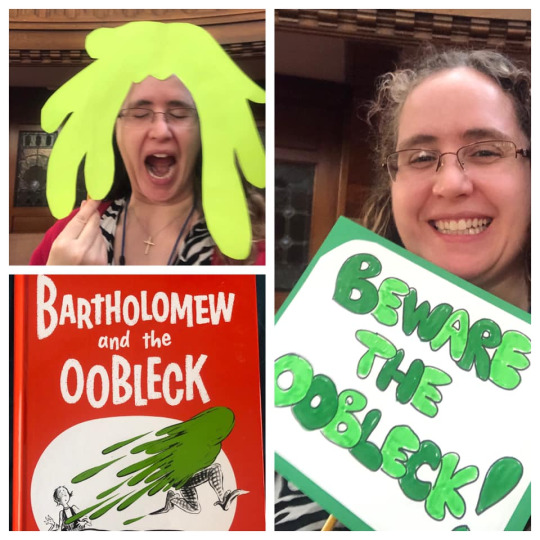

Bartholomew and the Oobleck: The Hardest Words (Matthew 6:5-15) - The Gospel of Dr. Seuss series #2, preached 3/8/2020

Last week, we started our series on the Gospel of Dr. Seuss with the story of one of Seuss’ most familiar characters – the Cat in the Hat – who taught us about grace and reminded us how important it is to know when to ask for help.

This week, we go back to an even earlier Seuss, one which is perhaps more unfamiliar to most of us: the story of Bartholomew and the Oobleck.

I don’t remember hearing this story when I was growing up – and when you remember that I grew up as the child of two elementary school teachers, that’s pretty surprising; I didn’t think there were any Dr. Seuss books I didn’t know. But Bartholomew and the Oobleck somehow flew under the radar: perhaps because the story doesn’t rhyme, or perhaps because level-headed Bartholomew isn’t quite as flashy of a hero as the persistently optimistic Sam-I-Am or the fun and funny Cat in the Hat.

So for your sake and for mine, let’s revisit the story of the Oobleck.

The story starts in the Kingdom of Didd, in The-Year-the-King-Got-Angry-with-the-Sky. And in an unlikely twist, the hero of the story is not the king but the page boy, Bartholomew. Then again, if you remember that this is a children’s book, it’s not so surprising that a child is the hero. Or if you’ve ever read the bible, if you remember the stories of David, the overlooked youngest son, or if you remember young Samuel’s call story, or the young person whose lunch fed thousands, or the king who was born in a stable, the Messiah who called us to have the clear-eyed faith of a child – then it’s not so surprising that a child sees more clearly than the proud and pompous king.

But anyway, back in the story, we learn that the King is a person who gets angry often. In this particular year, the King gets angry with the sky: he growls at the rain, he growls at the sun, he growls at the fog and he growls at the snow. And maybe you know people like this king, who spend their lives growling at things they cannot change – and who are so busy growling that they miss the beauty right in front of them. Maybe you’ve been a person like that; I know sometimes I have been: so caught up in the false feelings of power that anger gives me, that I miss what’s right in front of my face.

So here we have this King, angry with the sky, wishing for something NEW to come down. And because he is the King, he is determined to have exactly what he wants. The King decides to call for his royal magicians, to force them to make something new come down from the sky.

Bartholomew, the page boy, tries to get the king to slow down, to think his plan through, but the King won’t listen. And Bartholomew, bowing, says, “Your Majesty, I still think you may be very sorry.”

The king’s magicians are summoned, shuffling up from their secret hideaway, chanting their secret magical words, and the king commands them: “I wish to have you make something fall from my skies that no other kingdom has ever had before.”

And the magicians speak one word: “Oobleck.”

“Oobleck?” says the King. “What will it look like?”

“Won’t look like rain. Won’t look like snow.

Won’t look like fog. That’s all we know.

We just can’t tell you any more.

We’ve never made oobleck before.”

And as the magicians shuffle away to summon the Oobleck, Bartholomew begs the King to call them back. “I won’t stop them,” says the King, “not for a ton of diamonds! Why, I’ll be the mightiest man who ever lived! Just think of it! Tomorrow I’m going to have Oobleck!”

All night, while the king struggled to sleep, Bartholomew kept a sleepless and anxious watch, afraid of what the morning might bring. At first, when dawn breaks, it seems like the silly magicians have failed, but just as Bartholomew breathes a sigh of relief, he notices a wispy little green cloud. As the cloud comes closer, lower, he notices tiny little greenish specks.

Bartholomew can’t say why, but those green blobs frighten him. He wakes the king, who looks out the window in delight, even as the little specks grow bigger and bigger in size. The King calls a holiday: “I want every [one] in my kingdom to go out and dance in my glorious oobleck!” And he sends a protesting Bartholomew to ring the holiday bell… but the bell won’t ring; it’s full of sticky green oobleck.

And that’s only the beginning. Bartholomew sees a bird in her next, stuck in gooey, gummy, glue-y goop, and he realizes: if the green stuff sticks up robins, it’ll stick up people, too!

He runs to wake the royal trumpeter to sound the alarm – but a glob of oobleck flies right into the horn, and not a sound will come out. The trumpeter reaches inside to clean it – but he ends up with his hand stuck tight.

Bartholomew runs for the captain of the guards, who ignores Bartholomew’s frantic warnings, and – in an effort to prove his bravery – eats some of that beautiful green oobleck… and his mouth is glued shut. Bartholomew runs to get more help – but it’s too late. The oobleck is falling in globs as big as footballs; it’s too late to warn the people, who are already stuck in their fields and in the streets. The oobleck piles, still falling, until it breaks through the windows, pouring into the palace, and everyone ends up stuck, panicked, terrified, right where they are. No one can move – no one but Bartholomew, who carefully continues to avoid the green goo.

He runs back to the throne room, looking for the King – and there he finds him, “proud and mighty ruler of the Kingdom of Didd, trembling, shaking, helpless as a baby.”

Bartholomew finds the king, stuck to his own throne, his crowd stuck on his head; oobleck dripping from his eyebrows and oozing into his ears.

“Fetch my magicians!” he yells, but Bartholomew says, “It’s too late.”

“Then I must think of some magic words,” groans the king… until Bartholomew says, “Don’t waste your time saying foolish magic words. YOU ought to be saying some plain simple words!”

“What do you mean, boy?” asks the king.

“I mean,” said Bartholomew, “that this is all your fault. Now, the least you can do is say the simple words, ‘I’m sorry.’”

The king is flabbergasted; no one has ever spoken to him like this before. “Kings never say ‘I’m sorry!’ And I am the mightiest king in all the world.’”

“Bartholomew looked the King square in the eye. ‘You may be a mighty king,’ he said. ‘But you’re sitting in oobleck up to your chin. And so is everyone else in your land. And if you won’t even say you’re sorry, you’re no sort of a king at all!’”

Friends, Dr. Seuss wrote this book in 1949. He was inspired, he said, from a conversation he overheard while stationed in Belgium during World War II: during a rainstorm, a fellow soldier complained, “Rain; always rain. Why can’t we have something different for a change?”[1]

Knowing Dr. Seuss’ great imagination, that conversation caused him to dream up just what else might fall from the sky – and what might make that soldier more careful what he wished for.

But knowing Dr. Seuss, and knowing the world of the 1940s, it’s not hard to see a deeper caution in the story of Oobleck and the King. Just because we can do something, doesn’t mean we should. Just because we don’t intend devastation, doesn’t mean we aren’t responsible for the destruction that follows our choices. And pride, the desire to outshine our neighbors, our love of power and love of self – those are dangerous, devious motivations indeed. And if we are not careful, we just might end up being the reason that devastation rains from the skies.

It was an important message in the aftermath of the war, but it’s also an important message for us today: when we find ourselves stuck, mired in broken systems, watching devastation unfold around us, while those with the power to make changes stubbornly refuse to take any responsibility, to apologize, to change or to grow.

Friends, the systems we live in are broken. We are stuck. I don’t think that any of us, no matter where we fall on the political spectrum, can deny that we find ourselves divided on nearly every important issue, longing for a better system but unable to imagine one, feeling hopelessly gridlocked, just as stuck as if we were sitting in Oobleck up to our ears.

We’re stuck. We’re stuck with one person of wealth and privilege spending billions of dollars trying to prove they’d be a better leader than some other person of privilege and wealth… while for most of us, nothing changes at all; we’re stuck, lobbying accusations and insults at each other, while a virus preys on our prejudices.

We’re stuck in a society where women and minorities are still locked out of the rooms where decisions happen.

We’re stuck paying thousands and thousands each year for health insurance and even more thousands in copays and deductibles and medical expenses because we’re afraid of the cost of health care for everyone.

We’re sinking into the racism our forefathers mixed into the very foundation of our nation; we’re stuck in a cycle of inherited wealth for a few and generational poverty and despair for everyone else.

We’re stuck in a nation where we are so afraid of being taken advantage of that we’re willing to let children go hungry and veterans sleep under bridges while retirees freeze in their homes.

We’re stuck in the church, too. We’re stuck in a church that tries to cling desperately to the golden past and spends our time and energy preserving what we have rather than joining Jesus out in the world looking for the lost – and we’re stuck in a denomination that has spent decades and billions of dollars fighting over whether all really does mean all.

We’re stuck. We’re stuck; we’re overwhelmed, bogged down, mired in the hopelessness and helplessness of it all.

And this week, Dr. Seuss teaches us a very important lesson about what to do when we’re stuck. For one thing, when we’re stuck, sometimes the best thing we can do is listen to the children: to the voices of the young people, who haven’t been so hardened or become so comfortable that they’ve stopped dreaming of the way the world is meant to be. Bartholomew warned the king not to let his own pride guide him, much like the child in another story who was brave enough to admit that the emperor had no clothes. When we’re stuck, look to the next generation: their voices, their passion, just might help get us moving again.

But just looking for something new isn’t enough: before we can move in a new direction, we need to figure out how to get unstuck from the messes we’ve already made. I think often of the words of Greta Thunberg, the teenage activist who went on strike – and inspired a generation to rise up and demand action on climate change. When she was invited to speak at the Senate, Greta said, “Don’t invite us here to just tell us how inspiring we are without actually doing anything about it…”[2] Listening isn’t enough – not if we don’t figure out how to get unstuck and do something.

Last week, the Cat in the Hat taught us how important it is to ask for help. But this week, we learn it’s just as important – and often far more difficult – to say, “I’m sorry.”

It’s so hard to say, “It’s my fault.” It’s hard to say, “I contributed to making the mess we’re in today.” It’s hard to say, “I’m sorry.” We don’t want to admit our mistakes. We don’t want to confess we were wrong. We don’t want to have to change our minds or change our ways. We don’t want to learn, to be challenged, or to grow.

Even when, like the King of Didd, we can’t ignore the evidence of our mistakes, we’d rather sit, proudly stuck in our own messes, than apologize.

But Bartholomew forces the King to recognize that, just as his unbending pride got him into this mess, his unbending pride is what’s keeping not only the king but the whole kingdom stuck. Because the king’s sin doesn’t just affect him; his refusal to acknowledge or apologize means no one can move on.

And maybe that’s the lesson we need to hear, as we search for a way to get unstuck: maybe it’s time to stop pointing fingers and assigning blame – because until we are ready to acknowledge that we’ve all helped make the messes, until we are willing to admit the ways we’ve all be wrong, we won’t ever be able to get unstuck and start moving towards a new way of living, towards making things better, for everyone, together.

This season of Lent is traditionally a season of repentance: a time to take a good look at our lives, to confess where we’ve gone wrong, to do what we can to make it right, and to commit ourselves to turn and go in a new direction. This is a season to say “I’m sorry” – to God, and to the people we’ve hurt, to all those who’ve gotten stuck in the messes we’ve made – this is a season to say “I’m sorry” – and acknowledge the ways we’ve benefited from systems we may not have built, the times when we’ve been willing to be silent and look away rather than confront the hard truth – this is a season to say “I’m sorry,” recognizing that there is magic and power in this words; when we apologize with humility and honesty, when we say we’re sorry and we really mean it – we open the door for healing to begin.

As soon as the King of Didd finally confessed; when he sobbed out, “It is all my fault. And I am sorry…” all the oobleck began melting away. Our messes are rarely so easily cleaned up; it can take quite some time and effort for us to get unstuck, but until we are sorry, until we find those words, we cannot even begin.

Beloved in Christ, I am sorry. I am sorry for the ways the church has missed the boat. I am sorry for the ways the church has abused its power, for the times when church leaders have let their fear be bigger than their faith. I am sorry, on behalf of every pastor who has hurt you, who abandoned you, who kicked you out, who beat you down, and who told you your pain and grief were your own fault. And I am sorry, on behalf of every pastor who let you off easy, who told you only half the gospel, who never challenged you to examine the log in your own eye, who promised you heaven without showing you the kingdom of God here on earth.

I am sorry for the times when I should have said something – but I didn’t. I am sorry for the times when I should have listened – but instead, I said everything wrong.

I’m sorry. For myself, for this church, for the global church: I confess that we have failed. There are many things we’ve done right – but there are also many times when we have fallen short. We have not loved our neighbors as ourselves, and we have not heard the cries of the needy. We have served other lords than the Christ who comforted the hurting and unsettled the comfortable – and I am sorry. And I pray that, as we confront our sin, as we confess and repent, we may begin to find a way to move into the future God dreams for us to see.

I am sorry. But I’m not the only one who’s “stuck” today. So I ask you: what are you sorry for? What messes have you made? What is it that’s got you stuck? What do you need to confess before God? And what do you need to confess before others? Whose forgiveness do you need to seek out? Who is it that you need to forgive – so that, even if they’re not sorry, you at least can come unstuck? What broken relationships are you being invited, in this season, to try to set right? And what are the systems we are being called to take responsibility for – to apologize for the things we’ve allowed to go on for far too long, and to find that, as we take responsibility for what’s wrong, we discover we also have the power to help make it right.

Beloved ones, may we be strong enough to say we’re sorry. May we be humble enough to ask for help. And in our confession, in our forgiveness, in our faith, may we find again and again the power of grace.

O God, we are sorry. We have failed. We have let our pride lead us astray. We have chosen to sit stubbornly in our mistakes rather than admit where we’ve gone wrong. We have let ourselves get stuck – and we’ve let others sit, stuck, in our messes, too. O Lord, have mercy. Christ have mercy. Lord, have mercy. Hear us, as we cry out to you: hear us, as we name our sins, as we face our own responsibility for the messes around us. And Lord, by your mercy, by your grace, as we face the choices we’ve made that have helped get us stuck, may we also discover that we have the power to begin to clean up the messes, to transform puddles of oobleck into rivers of justice and oceans of grace. In the name of Christ, who hears us, who forgives us, who calls us to new life, we pray; amen.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartholomew_and_the_Oobleck

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/sep/17/greta-thunberg-to-congress-youre-not-trying-hard-enough-sorry

0 notes

Text

The Cat in the Hat Returns: VOOM! (Genesis 3:6-10; Isaiah 1:15-18) - The Gospel of Dr. Seuss series #1, preached 3/1/2020

My kids are artists. They are made in the image of a creative God, a God who delights in drawing rainbows across gray skies, who loves to paint the clouds orange, purple, and gold, a God who knelt in the mud to form beings out of dust.

My kids are artists. Like the God who made them, they look at the world and search for ways to transform it, to make something new, to bring color and manifest joy.

And I appreciate their creativity; I love how my children have learned to embrace their visions, to dream their dreams, to care enough about the world they live in to work to make it more beautiful. I love when their creative spirit leads them to new solutions to their own problems; I love when their creative spirit helps them made new friends, helps them try new things; I love when their creative spirit produces amazing artwork to frame and hang on our family walls.

I appreciate their creativity a little less, however, when they are so inspired that they try to skip the middleman and create their artwork directly on our family’s walls. Or floors. Or furniture. Or skin. Or clothes.

And by now, our kids know the expectations. They know that crayons and markers are only for paper – they know, because they’ve been taught, reminded, caught, punished, taught and reminded over and over again. They’ve had to clean up their own messes; they’ve learned just how hard it is to erase pencil marks off dressers and scrub markers from bedroom walls.

But sometimes, sometimes, the call of inspiration is too much to resist; sometimes, even though they know better, sometimes our little people just can’t help themselves.

Not too long ago, our five-year-old felt the creative spirit calling her, and she was moved to design a new art installation on our bathroom wall. She worked with a variety of media: pencils and crayons and markers and watercolors and lip gloss, brought together in pursuit of one glorious and colorful vision.

My daughter really is a great artist. But she also is a smart little girl, and even as she admired her handiwork, she knew that mom and dad would probably have very different feelings about what she’d done.

So she turned her pencil around, and started trying to erase the evidence from the bathroom wall. Unfortunately, that pencil eraser just made smudges and smears and made everything look worse.

But B didn’t panic. Fortunately, she was already in the bathroom, and there was a sink right next to her. So she started the water, and she dipped her paintbrush into the water, and she started trying to paint her masterpiece away.

The wet paintbrush did some wondrous things to blend the colors, but the art remained. So B turned next to the bar of soap. Again, she used her paintbrush, dabbing it first in the soap, then attempting to use the soap to swirl the colors away.

Again, she discovered a new artistic technique. But again, the artwork stubbornly remained.

And now she was starting to get a bit desperate. She reached for the bottle of hand sanitizer, pumped out a handful, and tried smearing it directly on the wall. Hand sanitizer is pretty strong, but mostly, it just transferred more of the colors to B’s hands, while leaving incriminating little handprints behind.

She reached for the towel, tried to wipe her hands clean, and tried to wipe the whole mess – the paint, the crayons, the markers, the gooey lip gloss, the water, the soap, the sanitizer – she tried to wipe it away. And she ended up with a colorful towel, and a smudged and blotchy wall, and a panic in her little heart.

She did the only thing left to do: she scrubbed her hands, balled up the towel in the corner, turned off the lights, closed the door, and walked away.

Maybe you can relate: maybe it’s been a few years since you created artwork on the walls, but maybe – like B, or like the Cat in the Hat – maybe you’ve made a mess which you only later discover you just can’t figure out how to clean up. Maybe it’s the words spoken in anger, which you just can’t take back – maybe it’s the email you wish you never sent; maybe it’s the money spent on an impulse which you later regret; or maybe it’s years of neglecting your physical health, only to reap the consequences… or years of letting your fears and insecurities keep you from doing what you really want to do, or trying something new. But no matter what you do, you can’t undo what you’ve done… and no matter how hard you try to fix it, to clean up the mess, you just keep seeming to make it worse.

Eventually, though, it catches up to us. Eventually, reality sets in. Perhaps it surprises you not at all to know that my daughter’s bathroom masterpiece was discovered… it was discovered by her older sister, her wholly unsympathetic older sister, who delighted in tattling, who took great joy in a superior attitude, who scolded and admonished her little sister… until mom and dad reminded her how, at the same age, big sister expressed her creative side with a bottle of red nail polish… all over the bookshelf, and the books, and the box fan, and the carpet, and the walls… We reminded her how her own creative spirit once inspired her to doodle with a permanent marker on the face of a flatscreen television… We reminded her how all of us have made messes, and we all make mistakes.

And suddenly, big sister didn’t have nearly so much to say.

Not one of us is perfect. We are made in the image of the creative God – but we fall short; we make mistakes along the way. All of us have, at times, whether intentionally or not, all of us have made messes of God’s good creation; all of us have disappointed God, and hurt others, and hurt ourselves; all of us have sinned.

And much like my five-year-old artist, much like the Cat in the Big Hat, we find that – try as we may, we just can’t fix it by ourselves. Everything we try just moves the mess around. It’s like a bad attitude: and maybe you manage not to yell at your boss, but instead you yell at the car that cuts you off on the way home; maybe you control your temper with the grandkids, only to let it loose at the server at the restaurant; maybe you keep your cool with your neighbor, only to scream when the kids won’t eat their veggies; or maybe you watch the news, and it makes you feel overwhelmed and anxious, and because no one on the TV listens to you anyway, you end up yelling at your spouse or your best friend instead. Everything we try just moves the stress around. Even if we get the mess out of our own house, we just set it loose in the world – and we can’t ignore it; no matter what we do, we can’t make it go away.

After trying and failing to clean the mess himself, the Cat in the Hat finally asks for help; one friend after another, Cats A, B and C and down through the alphabet all do their best – but nothing works, until finally we meet tiny Cat Z.

And the Cat in the Hat says,

“Z is too small to see. So don’t try. You cannot.

But Z is the cat Who will clean up that spot!...

“He has something called VOOM.

Voom is so hard to get,

You never saw anything Like it, I bet.

Why, Voom cleans up anything Clean as can be!”…

Then the Voom… It went VOOM!

And, o boy! What a VOOM!

Now, don’t ask me what Voom is. I never will know. But, boy!

Let me tell you. It DOES clean up snow!...

[And the Cat said,] “If you ever Have spots, now and then,

I will be very happy To come here again.”

Finally, the whole mess disappears: through the power of this mysterious Voom, which cannot even be seen – but which is the only thing with the power to make everything clean.

“Voom is hard to get,” the book says, and “Don’t ask me what Voom is; I never will know.”

But friends, I know what it is. And the good news is, it’s not “so hard to get” – all you have to do is ask.

Because Voom is the one thing that works, even when our own power fails; Voom is the one thing that can clean us when we can’t clean ourselves; Voom is the one thing that erases our failures and our sins, and allows us to start with a brand new clean slate. Voom is the love of God; friends, “Voom” is the Cat in the Hat’s word for grace.

You can’t control it. You can’t see it. But grace changes everything.

That’s what we see in our scripture for today: grace. In Genesis, a mess is made in the garden; a mess that the first people try to clean up, to hide with some fig leaves – but they can’t hide what they’ve done.

But then God shows up, and offers grace: even in the midst of judgment, they are given real clothing, to protect them in this harsh new world. And later in Isaiah, the prophet speaks to a people suffering in exile, a people who are suffering for their faithlessness, wallowing in the messes they’ve made, and through Isaiah, God promises: though your sins be like scarlet, I will cover them, clean them, fresh as newly-fallen snow.

We are entering the season of Lent: a season which invites us to take a good and honest look at our lives, to face up to the messes we’ve made, the mistakes we’ve tried to sweep under the rug, the flaws and failures we’ve hidden behind a smiling face – Lent invites us to acknowledge our sin. We all have fallen short. We all have made messes, all over the place.

But here is the good news: that’s not where the story has to end. The Cat in the Hat is finally wise enough and courageous enough to ask for help – and we can ask for help, too. And if we do, when we cry out to God, we are given the gift of grace: God’s power to heal us, to cleanse us, and to enable us to begin again.

I hope that my daughters never become so afraid of punishment or failure that they stop creating masterpieces. And I also hope that they are learning that our love is always stronger than our frustration, and no matter what mess they’ve made, if they ask us, we will help them make it right.

And friends, I hope that you know that God’s love for you is so much greater, so much deeper, so much more powerful and patient than our love could ever be. May you have the courage to keep seeking joy; may you have the hope to follow the divine and creative spark within you; and when you mess it all up, may you be strong enough to ask for help… and know that you will always be met with God’s amazing grace.

God, we thank you for hearing us when we ask for help. We thank you that we are not alone in our messes. We thank you for the gift of grace; for giving us voom – that invisible, undeserved, powerful grace. Give us the courage to ask for help; give us the joy that comes from doing the best we can; and by your grace, when we fall, help us start all over again. In Jesus’ name we pray; amen.

Note: this picture of my little Things meeting The Cat and his friends is a couple of years old, but it will always be one of my favorites! Thank heavens for these little mischief makers. They are worth all the messes. Always.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fasting and Slowing: An Ash Wednesday Message

I have always enjoyed travelling: whether it’s exploring a new hiking trail, finding a new playground for the kids around town, taking a road trip, going to a class or training, or getting on an airplane, there is something exciting about discovering a place you’ve never been before. Part of the magic is, I think, that traveling takes us out of our routines. Our normal rhythms, our normal daily worries and stresses, get put on pause for a little while. Even something a mundane as laundry and clutter takes a back seat when you’re living out of a suitcase or when you’re on the road. Instead, you’re able to focus on new experiences.

I have always enjoyed travelling… or really, to be honest, I’ve always enjoyed arriving. I love to explore new places, but I’m not as keen on the process of getting there: frantic packing and repacking, long hours in a car, eating whatever food you can scrounge up from a gas station or overpriced fast food stand, hurrying up, waiting, hurrying again, worrying, checking and rechecking that you remembered your ID and your cash and your confirmation numbers…

I enjoy arriving, exploring new places, but I sure do wish that there was a faster way to get there. Maybe that’s why, as a kid, I kept waiting for the day when the teleporter technology finally became a reality. Maybe that’s why my own daughters keep looking for secret doors into Hogwarts hidden behind portraits or inside unassuming brick walls. That’s why my husband keeps looking for a blue police box that’s bigger on the inside. And maybe that’s why all of us keep searching in every cupboard and closet for a shortcut into that wonderful world of Narnia.

You remember Narnia, don’t you? The magical kingdom C.S. Lewis imagined, into which four children stumbled through a secret passageway in an unassuming wardrobe. In Narnia, the children discovered wondrous creatures, had magical adventures, learned hard lessons about faith and friendship and hard work and hope and – perhaps most amazingly of all – when they returned home, it was as if no time had passed at all.

Imagine that: being able, anytime you want, anytime you need, to sneak away to a world full of fauns and talking lions, or maybe a warm and sunny beach, or an amusement park or a quiet mountaintop – to escape to a place where you can catch your breath, escape your to-do lists, allow your soul to be restored, and then – when you come back home, there’s no pile of mail waiting, no overdue bills, no thousand messages in your email inbox, no overgrown lawn, the milk in the fridge hasn’t even gone sour.

I keep looking for that secret portal: for a fast escape, and an instantaneous return. I have opened many wardrobes, pounded on the back walls of every closet, but I haven’t found it yet. Our family has knocked on every fairy door we could find – we’ve even made our own – but no doors have opened for us. \I’ve even looked for a secret passageway here in the church where, in our big box of church keys, there hangs not one but two keys intriguingly named “the Troll Doors.” I don’t know where or what that is, though to be sure, I’m not sure I want those doors to open anytime soon.

I still haven’t found the cupboard that leads to my private retreat. But there is one door in our home that opens into an unpredictable world of mystery and surprises. It’s a small door – only about yea high – a little door in the corner of the land of Kitch-En, behind which you’ll find the fickle and capricious Kingdom of Pots-and-Pans.

Maybe you have a little door like that in your house: a door which, when you open it, you never know quite what you’ll find. Perhaps it will be a delightful and orderly little corner of the universe, everything you need conveniently organized by type and style and size, pots piled like so many nesting dolls, and with every pot, a lid to be found. Or perhaps, more often, more likely, just nudging the door open sets loose a cascading crashing cacophony of metal, pans and lids and colanders and bowls spilling all across the floor. Or perhaps nothing pours out, because the contents have been so haphazardly and consistently wedged into that space that nothing moves at all. Like a game of tetris, like a game of jenga, you search desperately for the one loose piece, the keystone that will release the rest.

I hate that cupboard. Don’t get me wrong; it’s full of wonderful and necessary things, tools which we use to feed our family on a daily basis. But too too often, instead of putting our pots and pans carefully and neatly away, we take the fast and easy route: we take them out of the dishwater, open the cupboard door, throw the pieces inside, and then slam the door as fast as we can and hope for the best.

The thing is, that fast and easy path today is anything but fast and easy when tomorrow comes, when the piles have poured down into the black hole of the no-man’s land of dead space back in the corner – because that cupboard connects with the corner space by the stove, where there’s no door, no light, and where – to be honest – there really just might be a gate to Narnia but we just reach far enough that we’ll ever know. Every day finds one of us or the other on our knees, crying frustrated tears, screaming unkind and angry words, up to our waists into that cupboard, with piles of pots and pans and colanders and mixing bowls strewn around us, searching desperately for the right lid or the big frying pan or that one sauce pot in the size we know we need.

Which brings us to the season of Lent. Traditionally, this is a season associated with the practice of “fasting” – which means giving up some of our ordinary routines, letting go of something we’ve taken for granted, in order to shake up our lives and renew our gratitude and connection with God’s people: whether by spending one day a week eating nothing, or letting go of a specific kind of food, going meatless, or cutting caffeine, or letting go of processed sugar or eating out or unnecessary spending – giving something up, so that it forces us to think about what we really have, and what we really need, and what it is that matters most.

But as I’ve prepared for this season, I’ve been thinking about the other meaning of the word “fast” – as in: we live in a fast-food, quick-fix kind of world… but too often, just like our mess of pots and pans, the fast and easy solution today only leads us to an even bigger mess in the days to come. Instead, we need to plan for our journeys, to appreciate the time it takes to get there, and to make the better choices today so that we have what we need tomorrow.

And maybe the two meanings aren’t so very different: because in the season of Lent, part of the reason we fast is to force us to slow down, to think, to consider what we’re doing and where that road is leading us. When Jesus spent his time fasting in the wilderness, that time surely went slowly: but over those forty days of hunger pangs and prayer, he put his house in order, so that – when temptation came, he was prepared. And too often, the trouble we face isn’t an avalanche of kitchen tools – but it’s the way that our lives seem to come crashing down around us when trouble comes. When we reach for our faith, but we can’t find it – when we search for hope, but no matter how far we dig, we can’t figure out where it’s gone – or when we come to the end of our lives, and we look around at everything we spent our time and our energy on, all that we traded the days of our lives to build, and it’s nothing but a house of cards crashing down, nothing but vanity, just dust in the wind.

This season invites us to fast by going more slowly. This season invites us to take some time to put our houses in order – literally, perhaps, by tackling those corners and piles of clutter that cause us anxiety; by digging through our piles of stuff, by cleaning up the messes, by weeding out the things we don’t need any more, and releasing them back into the universe, and finding ways to make things easier for us in the days to come. But this is also a time to put our inner houses into order – to open the doors we’ve worked so hard to keep closed. This is a season to come face to face with all those feelings, those memories, those parts of ourselves which we’ve tried to shut away – maybe because it was the only way we knew to survive at the time, but now, the time has come to open the door and face the mess that hides inside. It’s time to come face to face with our grief; to name what we’ve lost, and what it meant to us, and what it still means for who we are today. It’s time to come face to face with our guilt; to recognize the ways we’ve failed, the people we’ve hurt, the needs we’ve ignored, the things we’ve tried to run away from. It’s time to come face to face with our fear; to name the worry that keeps us up at night, to recognize the anxiety that lurks beneath the surface every day, and to take the power we have to face what we can, and to accept what we can’t, and to discover that sometimes the monsters that keep us up are nothing but bunnies made of dust.

It’s time to let go of what we don’t need any more – and it’s time to think of what we do. Just like nesting our mixing bowls and colanders makes it easier for us to be fed tomorrow, what would it look like for you to put your spiritual life in order? To practice now what you’ll need when those hard times come – to wrestle with the hard questions now, while you’ve got space to breathe; to consider what it is that matters most, and just how far you’re willing to go for God; to revisit the story of hope and justice in the scriptures, to spend time in the presence of the God who loves you, to start writing down something you’re grateful each day, and to start intentionally weaving prayer into your life? How can you use this season to put your house in order, to learn to love God better, and to love your neighbor better, and to love yourself, too?

The reality we face tonight is that there are no shortcuts – but at the same time, we are reminded that, for all of us, time is short. Let’s not waste it digging angrily through the messes we’ve made, or wishing away the journey of our lives, or pushing frantically against the closet doors where we’ve hidden our shadows away. But let’s commit ourselves, during this season of Lent, to slowing down, to doing the hard work, to making our spiritual homes places that we really want to live, for the rest of our lives – however long that may be – and places where we will be able to find peace, in our hearts and in our souls, when the time comes to go on to our eternal homes.

May God give us courage to open the difficult doors.

May God give us power to face what we find there.

May God give us patience for the road that lies ahead.

And always, always, may the only thing that overflows and crashes down around you in waves be the peace that passes all understanding, the unfailing peace that comes from God alone.

O God, in this season of prayer and preparation, be with us. Help us, as we open the doors we’ve worked so hard to close. Help us, as we sort through the unexamined moments of our lives. Help us, as we strive to live with intention. And help us to slow down: to breathe deeply, to rest well, to be renewed in faith, restored in hope, and wrapped in peace. In the name of Christ, who prays for us and who walks with us, we pray; amen.

0 notes

Text

Justice, Mercy, and Grace (Faith at the Movies: Just Mercy) - Isaiah 1:10-17; preached 1/26/2020

I’ve really enjoyed this Faith at the Movies series. We’ve had fun the last few weeks – talking about Disney princesses and Jedi battles – though even in those fantastical universes, we’ve recognized the battle of good against evil, and the risk faced and the power held by ordinary people to confront their privilege and face injustice. But today, those themes come into the real world, and real lives are at stake.

And I start by saying that, as I prepared for this Sunday, the thought that kept coming back to me over and over again is: I should not be preaching this sermon. That’s not to say that I shouldn’t be preaching this sermon, but what I mean to say is, I should not be preaching this sermon – not because this conversation is not important, but because I’m me: I’m not a person of color; I’m a white cis straight woman… and while the world doesn’t always appreciate the voices of women, especially in ministry, the reality is that, as a cis straight white woman, I am very aware that people like me have far too often been treated as a precious commodity, to be defended and protected at all costs. In the name of people like me, injustices and violence have been heaped upon my trans sisters and people of color – especially men of color – even though, rarely, has anybody tried to trust or protect people like me against cis straight white men, who are actually historically our biggest threat.

But I stand here knowing that the accusations of white women, the suffering and fear of white women, has been used over and over throughout history to justify prejudice and discrimination and imprisonments and railroading and lynching –and for that truth, and for all the ways I myself have over the years intentionally or not participated in a system that privileges me and devalues others’ lives and experiences – I stand here humbled, ashamed, full of sorrow and regret.

I have wrestled this week with my place in this story – the story of a black man sentenced to death for the murder of a white woman, a murder he didn’t commit; a black man whose continued imprisonment is justified in the name of letting white women sleep well at night. But I’ve also recognized that this same black man was freed not just because of the efforts of his lawyer but the tireless and risky work of another white woman – a woman who saw what was happening, and knew it was wrong, and refused to be silent or just go away.

Maybe I’m not the best person to preach this sermon. But I also know that, as a woman, I am grateful when my white male colleagues stand and name from their pulpits the experiences of their female and minority colleagues – so here I stand, naming my own participation in broken and sinful systems, but choosing to use the platform and the voice I’ve been given as best I can.

So let’s talk about Just Mercy. Let’s not just talk about the movie, but the true story, the real life which inspired it: the life of Walter McMillian.[1] Walter was born in 1941, and he grew up poor, picking cotton in Alabama. As an adult, Walter made good – he purchased logging and mill equipment and began his own business. He married, raising nine children with his wife of twenty-five years – but he made waves in the community when he had an affair with a white woman – and when one of his sons married a white woman.

Walter’s connections to white women – the ways he was seen to step “out of line” – made him an easy mark for suspicion, when another white woman, an eighteen-year-old dry-cleaning clerk, was shot and killed.

At the time of the murder, Walter McMillian was at a church fish fry, with dozens of witnesses – including a police officer. Nevertheless, a few months later, Walter was arrested – by a newly-elected, openly racist sheriff who was feeling pressure to solve the crime.

Walter McMillan was immediately sent to death row, where he waited for more than a year for his trial to begin. Did you hear that? He was sent to death row before his trial even began. The trial was moved to an overwhelmingly white county, where an overwhelmingly white jury, after a trial which lasted less than two days, found Walter guilty. The jury ignored the multiple witnesses who testified that Walter was at a church event. The jury ignored the lack of physical evidence or motive. The jury recommended a life sentence, but the judge – whose name was, this is the honest truth, Judge Robert E. Lee Key, Jr. – the judge overruled the jury – not to protest the miscarriage of justice, but instead to sentence Walter to death.

This was in 1988. This is recent history, friends. This was the eighties: when we thought we were finally past the chaos of the civil rights movement, when good white people said we don’t see color and everybody can just be friends. This happened in my lifetime, and in many of yours.

A couple of months after Walter was sentenced to death, and well into his second year on death row, a young attorney named Bryan Stevenson visited Walter in prison. The two men bonded over their common life experiences, especially their faith, and Stevenson was moved to help Walter fight for freedom. Over the next three years, the Alabama Court turned down four appeals in Walter’s case. But then the key witness – really, the only witness – against Walter McMillian recanted: he confessed that he was put under pressure by law enforcement to lie, to place Walter at the scene of the crime, or else to face death row himself.

In the movie, this is the moment when you finally start to believe that the good guys could win – this is the moment when Walter himself, who’s refused so far to get his hopes up, when Walter starts to believe he might get his life back. Walter and his lawyer petition for a new trial, showing the evidence that was faked, the evidence that was ignored, all the evidence that Walter is an innocent man.

But then the petition is denied. Walter McMillian goes back to death row – heartbroken, devastated, after that hope, which he’d resisted for so long, fails him again.

But Stevenson doesn’t give up. Walter doesn’t give up. They keep telling the story: inviting the media to bear witness, inviting the public to hear what’s happened, getting the momentum to shift to the point where those in power can’t ignore it anymore. And after six years on death row, after six years of brutality and despair, after six years of protesting his innocence, Walter finally got a new trial. He was exonerated; his name was cleared; and Walter got to go home.

It’s a happy ending – but it isn’t. Because Walter McMillian carried the trauma of his years on death row for the rest of his life. And Walter McMillian’s community, his children, never forgot that their lives could be ended just because someone thought they “looked guilty.” And Walter McMillian is not alone. Although the prosecutors claimed that Walter’s eventual release proved that the system worked, the reality is that – as his lawyer Bryan Stevenson said – “it was far too easy to convict this wrongly accused man… and much too hard to win his freedom after proving his innocence.”

This is a powerful movie. It’s all the more powerful because it’s grounded in truth. But it also begs the question: how could this happen? And what’s terrifying is the realization that this story still plays out – innocent people are underrepresented, railroaded, convicted, even executed – all around us still today.

The systems that are supposed to protect us are broken. Systems are made by people, and people are messed up and broken, unwilling to acknowledge our prejudices, unwilling to face our mistakes, far more concerned with keeping up appearances and offering the illusion of justice than we are concerned with seeking actual justice based on the truth.

One of the protests offered again and again by those who refused to reopen Walter’s case is that “my neighbors deserve to sleep well at night” – as if having someone locked up, even if it’s the wrong someone, as if having the illusion of security is what really matters.

But the question is asked, “Whose neighbors?” Whose neighbors deserve to sleep well? Whose neighbors matter? Do you think that the people in Walter McMillan’s neighborhood slept well at night? Men and women and children who’d been with their neighbor, their father, their friend, who knew he was innocent, and still had seen him condemned to death for a murder he couldn’t possibly have committed?

What about us? Do we prioritize our own sleep over the sleep of innocent men on death row? The sleep of mothers, living in terror that their sons will one day be gunned down just for being black? What about the sleep of children separated from their parents at the border? The sleep of women who’ve been victimized but know if they come forward, their lives will just be destroyed all over again?

Who gets to sleep well at night? On the night before his own death, Jesus scolded his disciples for the inability to stay awake, to pray and keep watch with him – are we, too, guilty of sleeping while others weep?

It’s easy to talk about loving our neighbors – but as Just Mercy asks us: where is our neighborhood? Who are our neighbors? Jesus never gives us the luxury of limiting “loving our neighbors” to the people who look like, think like, believe like, or act like us.

And you know, for a religion that laments the sacrifice of an innocent man, for a religion that proclaims that one death is enough, and no one else has to die for their sins – or anybody else’s, for a religion that celebrates grace in the name of Christ, we sure have hurt and killed and ignored the suffering of a whole lot of people in his name.

When black men are shot in parks and traffic stops, we find ways to say it’s their own fault. When women are attacked, we immediately ask: what was she drinking? Why was she dressed that way? When violence breaks out, we breathe a sigh: it’s not in my neighborhood. When the water runs dirty for years on end, we shrug our shoulders – because our tap water is safe. Or at least we hope so. When mosques and temples are defaced and bombed, we look away; it doesn’t threaten me. And when the so-called justice system is in fact a travesty that privileges rich white people while overwhelmingly punishing people of color and threatening immigrants and refugees and terrifying victims out of telling the truth lest they be punished and victimized all over again –

When rich white men play with fidget spinners rather than hearing evidence, because they’ve already made up their minds, and because the lies are more profitable than the truth –

Then we are a very long way from the days the prophets dreamed of: when justice will roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream, where the young have vision and the old dream dreams, and there is neither Jew nor Greek, male nor female, black nor white, slave nor free, but we are all one in the peace and the grace of Christ.

Walter McMillian was almost executed for a crime he was innocent of; the system that was supposed to protect him let him down. But he’s not the only one. In fact, based on continuing work to secure new trials for those on death row, for every nine people who are executed in our country, at least one person is proven innocent. One out of ten. That’s unacceptable. That’s heart-breaking.

But even for those who are guilty – as Just Mercy reminds us, no matter what you’ve done, you are more than your worst act. Isn’t that exactly the gospel that we proclaim here every week? We celebrate the promise of grace for the foulest sinner, grace that saves wretches like me. In God’s eyes, there is no such thing as a lost cause; even the worst criminal can, by God’s grace, be forgiven, redeemed, become someone new. Just look at the heroes of our faith: Moses was a murderer. David was a sex offender and a murderer. Paul breathed hatred and murder against the early Christians. But God used every one of them – even the criminal who died by Jesus’ side, who had no time to turn his life around, no time to redeem himself or atone for his mistakes – even he was promised a place at the feast of God in glory.

We don’t get to kill people because they scare us. We don’t get to kill people because we don’t like the way they look. We don’t get to condemn people to death because they live on the wrong side of an imaginary line, or because they were born poor, because their skin is a different color, because they don’t fit in, because they follow a different faith. We don’t even get to condemn the worst criminal out there to death – because Jesus had something to say about throwing the first stone, and because – let’s face it – we are really good at getting things wrong. More than that, friends, we are people of life. We are people of grace.

It’s not popular. It’s not easy. In Walter McMillian’s story, Walter’s family and friends were pressured and threatened; Walter’s lawyer and his colleagues faced death threats; the key witness had to overcome his own terror and trauma to risk telling the truth; the prosecutor had to face the guilt and embarrassment and responsibility of getting things so wrong.

Speaking the truth is risky. Forgiveness is dangerous. Loving the wrong kind of people, eating with sinners – that’s exactly the sort of thing that got Jesus crucified.

And he said, “Take up your cross, and follow me.”

We are not promised that the road will be easy; it certainly won’t be comfortable or convenient. But we are promised that Christ will be with us, even in the shadow of death, even to the end of the age; we are promised that the truth will set us free. And we are promised that God’s grace will always be sufficient for our needs.

So let’s keep speaking truth. Keep facing difficult truths: like the reality that racism is built into the foundation of our nation, and some lives have always mattered more than others, and the death of a few innocent black people or desperate brown people has always been considered a reasonable sacrifice so long as white people can sleep well at night.

That’s the cold hard truth. Some of us have had the luxury of ignoring it for too long: but we can’t pretend any more.

Do you remember, back when our nation was debating whether or not we should welcome refugees – something we’re still debating, but much more quietly, while our government distracts us and keeps turning desperate people away… do you remember, someone used the analogy which compared refugees to candies? And they said, “Would you eat a bowl of candy, if you knew that one or two might be poisoned?” – with the implication that we shouldn’t possibly invite refugees and immigrants into our country, when a few of them might turn out to be criminals. Not like we don’t have enough homegrown terrorists already, but that’s another story…

When I remember from that conversation was when someone came up with the perfect response: He said, “Are the other candies human lives? Like, is there a good chance, a really good chance, that I would be saving someone from a war zone and probably save their life if I ate a candy? Then I would GORGE myself on candies. I would eat every single one I could find… And when I found the poisoned candy and died, I would make sure to leave behind a legacy of children and of friends who also ate candy after candy until there were no candies to be eaten. And for every person who found the poison candy… we would weep for their loss, for their sacrifice, and for the fact that they did not let themselves succumb to fear but made the world a better place… Because [the] REAL question [hidden behind an inaccurate, insensitive, dehumanizing candy metaphor] is, is my life more important than thousands upon thousands of men, women, and terrified children… and what kind of monster would think the answer to that question is yes?”[2]

I know we were talking about the death penalty, but it’s all connected: because whenever we allow ourselves to be guided by prejudice and by fear – we’ve lost our way. When did we start believing that one life doesn’t matter, unless it is our own? I’d much rather err on the side of grace and compassion than hear about one more child dying in an American concentration camp, or one more teenager taking their life because they’re afraid to be who they really are, or one more innocent person executed by our government in our name.

The problems are daunting. The systems are broken. And one person can’t fix it all. But each one of us can refuse to give up and to give in. We can choose to repent, to acknowledge our own prejudice and complicity, to name our own fear. We can search out truth, and call out lies – even when they come from the mouths of people we love. We can commit to a much broader definition of our neighborhood, and try to love and work for the good of all God’s children who live there – and when we fail, when we get discouraged, we can give thanks for God’s grace which is more than enough to cover our sins, and we can help each other find the hope and the courage to get up and start again.

I want to end today with the words of Bryan Stevenson – the real Bryan Stevenson, the man who fought for so long to get Walter McMillian free, who dedicated his career to freeing other innocent people from wrongful convictions:

Bryan Stevenson says, “We are all implicated when we allow other people to be mistreated. An absence of compassion can corrupt the decency of a community, a state, a nation. Fear and anger can make us vindictive and abusive, unjust and unfair, until we all suffer from the absence of mercy and we condemn ourselves as much as [we] victimize others. The closer we get to mass incarceration and extreme levels of punishment, the more I believe it’s necessary to recognize that we all need mercy, we all need justice, and – perhaps – we all need some measure of unmerited grace.”[3]

Thanks be to God, for justice, for mercy, and for unmerited grace.

O God, we have all fallen short of your glory. We have all sinned. We have not loved our neighbors as ourselves. We have not heard the cries of the needy. We have looked away from injustice. We have thought too often only of ourselves. Lord, have mercy. Christ, have mercy. Lord, have mercy. Forgive us for privileging power over people. Forgive us for choosing comfort rather than change. Forgive us for choosing crucifixion, when you’re a God of resurrections. Transform us. Teach us to love others as you love them. Teach us to love others as we love ourselves. Teach us to seek truth, to do justly, to love mercy, and above all, to walk with humility and love. In the name of Christ, who redeems us, who forgives us, who calls us to new life, we pray; amen.

Note: The photo above includes a portion of the United Methodist Church baptismal vows; along with rejecting evil, repenting of our sins, and putting our whole trust in the grace of Jesus Christ, candidates are asked: “Do you accept the freedom and power God gives you to resist evil, injustice, and oppression in whatever forms they present themselves?” Methodism (and the early church, and Jesus himself) has always linked the personal and social gospel; we are called to live out our faith in the world.

[1] The story is drawn not just from my movie notes, but from this article, which helped me fill in the gaps: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_McMillian

[2] https://www.joe.ie/news/broadcaster-eli-bosnick-with-a-far-more-humane-skittles-analogy-561050

[3] https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/6591318-we-are-all-implicated-when-we-allow-other-people-to

0 notes

Text

Our Holy Little Lives (Faith at the Movies: Little Women) - preached 1/19/2020

Movie Summary (spoilers – but if you don’t know the basics of Little Women 150 years after the story was published, I think it’s a bit late for spoiler warnings!): Little Women is based on Louisa May Alcott’s novel of the same name, and tells the story of four sisters coming of age in the 1860s. Their father is serving as a chaplain in the Civil War, so their wise and patient mother heads the household. The four sisters each have unique personalities: from oldest to youngest, they are Meg, who’s beautiful and traditional; Jo, who rejects tradition, longing to be independent and a writer; Beth, the peacemaker of the family; and Amy, the youngest, who loves art and longs to be rich. The family starts a friendship with their rich neighbor and his grandson, Theodore Laurence, whom they call “Laurie.” Meg falls in love with and marries Laurie’s tutor; Jo refuses Laurie’s marriage proposal and instead goes to New York City in search of adventure. Amy travels to Europe with the girls’ wealthy maiden aunt, while Beth’s health fails back at home. Before her death, Beth begs Jo to keep writing stories for her. Jo realizes she longs to love and be loved, and second guesses her refusal to marry Laurie – only to discover that Laurie has married her youngest sister, Amy. Jo ends up falling in love with a professor she met in New York City, who encouraged Jo to push herself beyond writing fantastical stories and instead capture the beauty of real life.

As Jesus and his disciples were on their way, he came to a village where a woman named Martha opened her home to him. She had a sister called Mary, who sat at the Lord’s feet listening to what he said. But Martha was distracted by all the preparations that had to be made. She came to him and asked, “Lord, don’t you care that my sister has left me to do the work by myself? Tell her to help me!” (Luke 10:38-40)

I always hated Amy March.

Maybe it’s because I was the youngest in my family, too, so I saw a little too much of myself in Amy, the youngest sister, desperate to stand out, longing for attention and a chance to outperform her older siblings.

But I always detested Amy March. The four sisters are each unique: there’s Meg, the oldest, smart and sensible; there’s Jo, fearless and bold – often to the point of foolishness; there’s Beth, the shy sister who sits quietly in the background and asks why everyone can’t just get along – and then there’s little Amy, whiny selfish Amy, fiercely and relentlessly ambitious Amy.

The March family is far from wealthy; though they do get glimpses of neighbors who are much worse off, they also live in the shadow of their rich neighbor’s estate, and more often than not, the family goes without. And so Amy is bound and determined that she won’t be poor forever; she is going to be a rich woman, no matter who she has to marry to get there.

Amy is vain, perhaps because she knows her beauty is her one greatest asset in capturing a rich husband; she yearns to be popular in school, and she hates being left behind. So when her older sisters leave her behind to go out for an evening of fun, Amy yells, “You’ll be sorry!” – and then with anger and intention, she takes her older sister Jo’s masterpiece, her handwritten manuscript, the novel into which she’s poured her heart and soul over many sleepless nights – Amy takes Jo’s one precious labor of creative love, and she burns each page away.

The sisters get in an actual rolling-on-the-floor, fists-flying and hair-pulling fight that night. And when Mike and I watched that scene – both sisters sobbing with anger, both sisters certain she was the one who’d been done wrong – when we watched those sisters yelling and rolling and fighting, I looked at my husband and said, “Isn’t it nice to know that sisters are the same in every generation? Some things just never change!”

No matter what age we live in, we fight most passionately – and hurt most deeply – the people whom we love most dearly. Maybe it’s a simple matter of proximity. Maybe it’s because we reserve our civility for those people we can keep at an arm’s length. Or maybe it’s because deep down we believe that love will persevere – they say that’s why children will behave beautifully for teachers and neighbors and strangers, but as soon as their parent shows up, everything goes off the rails… the experts say it’s because our children know they’re safe with us; they can let their guard down, and let their sadness or anger or exhaustion show, and they know we’ll still love them, no matter what.

Maybe. But – when we’re honest – there are plenty of days when we make it hard to love each other. And that’s what happened for the March sisters the night Amy threw Jo’s masterpiece in the fire. Even when she repents and apologizes, weeping, the damage is done, and Jo proclaims, “She doesn’t deserve my forgiveness. I hate her. I’ll never forgive her. Never.”

It’s only later – only after Amy chases after her older sister, begging for forgiveness, her cries falling on deaf ears until the splash, until Amy falls through the ice and nearly drowns in a frozen lake – it’s only later that Jo relents, rushing to her sister, pulling her to dry land, wrapping her in Jo’s own warm dry clothes, and forgiving her at last. Jo realizes, in that moment, just how quickly things can change; she realizes that even more important than irreplaceable manuscripts are irreplaceable people. Jo realizes what matters most – and, as she later says to a grown-up Amy, “Life’s too short to stay mad at your sister.”

And I know that Jo is right – I spend my whole life talking about grace after all. But I’m not sure I’d be so quick to forgive. I never really liked Amy to begin with, and this whole scene especially reveals just how selfish and ungrateful she can be. And I know, in my rational mind, that people are always more important than things. But still, the heart struggles to forgive sometimes.

I never could stand Amy. Then again – and this may be close to blasphemy – but I never really liked any of the March sisters. I loved their story; I loved to visit their chaotic little household, but the sisters themselves had a way of getting on my nerves. There’s Meg, who gives in to peer pressure when the rich girls adopt her as their pet… and who rather enjoys playing the part, until she gives into pressure from the neighbor-boy to put her airs away. And Meg is always just a little bit too earnest, too good; she gives up her own dreams for the sake of love.

Then there’s Beth, who never really has many dreams or much of a voice, just meekly letting the story pass her by – Beth, the one whose own sisters even think she’s just a bit too good to be true.

And even Jo, the plucky heroine who bucks tradition, clinging to her independence, determined to keep her voice and make her own way – even Jo ends up compromising, giving up her freedom to marry in the end. Jo made me furious growing up: she is so determined not to marry that she breaks the heart of the neighbor-boy, turning down his proposal, even though he would have been such a perfect match… but then all of the sudden she changes her mind and marries anyway, marrying somebody else whom we, the audience, hardly get to know or have any chance to approve. Sure, I could make an argument that the whole arc of Jo’s story, the essence of her character, is that she doesn’t give in to other people’s opinions of what her life should be – she won’t be pressured into compromising her choices just to meet someone else’s expectations, so perhaps it only makes sense that she doesn’t care whether I approve of her decisions, either.

Maybe. But my goodness, it was always just so annoying to watch this fiercely independent woman throw her whole personality away.

So that’s the family: four irritatingly flawed sisters, and their mother – Marmee, who’s more than just a little bit too good, Marmee who bravely heads the family while father is away, Marmee who believes in educating her daughters to be independent women, who teaches them not just ambition but compassion for their neighbors, Marmee who is infinitely patient with her wild girls and somehow always knows the very right and perfect thing to say.

It’s altogether a bit too much – which is, I think, why I appreciated this newest telling of the March family story. This film humanizes the March family and, in many ways, redeems them. Instead of saccharine perfection, wise words and quick forgiveness, we see more of the conflict and chaos. We catch glimpses of the struggle that patient Marmee faces when she confesses that she is angry every single day. We see that Meg, who achieves the perfect domestic little life, who pledged that she’d rather marry a poor man for love than anyone else – Meg marries her poor man for love, but still is the young woman who loves fine things, and struggles at times to be content. Beth the wallflower becomes a bit bolder, more of an actor in her own story, and in many ways the thread that holds the others together, even after her death. And we see a Jo who doesn’t forget herself for a man, but who instead clarifies her own priorities – and chooses to live, in her own ambiguous way, happily ever after.

But most of all, we get to meet a kindler, gentler Amy. We see Amy not as a spoiled brat but Amy who’s lonely and longing to be loved. We meet an Amy who has grown up in the shadow of hardship and war, of poverty and death, and who is desperately afraid she will die unimportant, unnoticed, that she will die without ever really getting a chance to live. And we meet an Amy whose marriage, in the end, is not so much a greedy manipulation but is an extension of her love for her family, and her grief, and her longing to be loved for herself, and the pressure she’s always felt to be the one who finds a way to provide for all the rest .

In this modern Little Women, each of the women are doing their best to make their way in the world – each choosing a different path, and each stumbling along the way to figuring out what love and happiness means. We find that none of the sisters is the caricature we’ve reduced her to; we find that none is so flawed nor so perfect as they’ve seemed – this new incarnation of the March family is not quite so pure, and for that reason, it’s so much more real.

Because that’s what Incarnation means: it means in-the-flesh, in the real world of flesh and blood and sweat and tears. And that’s where the Incarnate Word, who put on flesh and lives among us, that’s where God meets us – not in some patient, perfect, harmonious universe, but in this one where we really live.

It’s a bit peculiar, watching a movie knowing you’re going to preach on it in a few days. I’m always trying to take notes, jotting down the best lines and the things that really make you think – but this time, I found that my favorite scenes were the ones I couldn’t capture in my notes, because they were the moments when the whole brood of sisters are talking over each other – in joy, or excitement, murmuring words of comfort or exclamations of praise – and in those amazingly chaotic moments, there is just so much warmth and so much love.

And when the March family ultimately loses one of their members, when quiet Beth really and truly fades right away, that’s when the sisters realize just how not-invisible Beth really was – how much her very presence meant – and more than that, they realize just how precious all those ordinary little moments of their ordinarily little lives always have been.

Meg always longed for her own household, and Amy wanted riches, and Jo yearned for grand adventures – but when they lose Beth, they realize that what matters most, the grandest and richest adventures, came in quietly, in ordinary moments: in family newspapers and attic dramas, in family breakfasts and hair disasters, in missing gloves and burnt dresses and secret mailboxes and singing around the piano by candlelight… they learn to find the beauty and value in all that ordinary stuff.

I imagine that’s why Jesus sought the company of sisters like Martha and Mary, whom we visited again today, on what was undoubtedly not one of their finest days. But Jesus the wandering rabbi was a man without a home, looking for a place to let down his guard and rest – and in his presence, even sisterly squabbles take on the air of something holy. Have you ever considered how remarkable it is that we know this story at all? That the story of two sisters fighting over housework was considered so important that it actually becomes part of the gospel – the story of salvation, the story of heaven come to earth, the story which was preserved and passed down through the generations? It’s not just crowds and miracles and sermons and speeches, but we find that the chaos of our daily lives is holy, too. Even when we’re not at our best, even when we get on each other’s nerves, love is there, and God is, too.

Little Women is of course a story about a family of remarkable women, but there is an honorary brother in this family, the rich and lonely boy next door. And when that boy first encounters the chaotic bustle of noise and affection inside the March household, his face reflects his longing – a longing to belong to a crazy and boisterous and loving family like theirs. The arguments and embraces are holy, because they are bound together with a thread of love – and having everything means nothing if you have no one to share it with.

Jo spends the whole novel trying to write great stories; she writes about kings and princesses, about murderers and star-crossed lovers and great and mighty battlefields. Jo writes stories about scandal and passion and gore – but what she realizes in the end is that the best story, the greatest and most important story, is her own.

Beth begs her sister to keep writing, even after Beth herself is gone. And in the writing, Jo finds that the stories are holy – in the writing, she finds that her sister lives on. Love doesn’t end with death: we know it, we proclaim it, and Jo learns it – not by facing down a dragon on a battlefield, but by discovering the love that has been with her all her life through.

That’s the beauty and the genius of Louisa May Alcott’s book – she who identified with Jo, who searched for a great story and found her story very close to home. Alcott’s characters reveal to us that every day is a holy day, and ordinary moments can be the holiest of all.

And this is a message which is very personal for our family. Many of you know that we lost our son to leukemia when he was just one year old. Shortly after our son passed away, we sat with a friend of ours sharing photos and watching videos and telling stories through our tears, and our friend asked us, “Is there one memory, one moment, that you really treasure most of all?”

And we said, “Honestly? It’s the stupid ordinary everyday family stuff: the stuff that we used to take for granted.” It’s the afternoon when our kids drummed together on the bottom of a garbage can, or the nights we actually all sat around the same dinner table, or we shared snuggles and had a tickle-fight at bedtime – it’s the seemingly ordinary moments that matter most. Carl’s big sister trying to “read” him a book. Going for a walk around the neighborhood. Playing with my parents’ dog. Crying in the carseat. Laughing as he spins around and around in an office chair. Holding him while he naps. Stupid, ordinary, everyday family stuff.

That’s what matters. That’s why the March family story endures: not just because each sister, in her own way, learns that the most important thing in life is love – but because, for all their grand dreams and ambitions, they discover the real adventure and the best story is our own. One of the sisters muses, “Do you really think anyone would care about our little domestic struggles and triumphs?” The answer throughout the years has, of course, been yes – because we are reminded that the real stuff of our daily lives matters, too.

Friends, what is your story? Who shares it? Where has God been revealed in your life? What do you want to remember forever - not just the best days, but the ordinary ones? What legacy are we going to leave behind?

Our little lives matter. This day, this day right now, is the day that the Lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it. And may we find that this day is a holy day – flaws and squabbles and all.