All the words. Gordon Ross, VP/Partner OXD, Vancouver.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Quote

The problem, if there is one, does not lie with sloppy data collectors; it lies with our continued reliance on two-cultures dichotomies, in which objectivity and subjectivity can be neatly separated and human messiness can somehow be avoided in data collection performed by humans (or with automated devices created by humans). When we imagine that datasets of properties like step counts speak for themselves, we negate the responsibility we hold for determining which properties will be expressed as data, in what form, and with what parameters.

https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/the-myth-of-objective-data/

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

the value of cases

“Good case studies inspire theory, shape ideas and shift conceptions. They do not lead to conclusions that are universally valid, but neither do they claim to do so. Instead, the lessons learned are quite specific. If one immerses oneself long enough in a case, one may get a sense of what is acceptable, desirable or called for in a particular setting. This does not mean that it is possible to predict what happens elsewhere or in new situations. Dealing with whatever is different always requires work and logic does not do work. They are not actors, but patterns. Thus, the logic of care articulated here only fits the case that I studied. It does apply everywhere. This is not to say its relevance is local. A case study is of wider interest as it becomes a part of a trajectory. It offers points of contrast, comparison or reference for other sites and situations. It does not tell us what to expect - or do -- anywhere else, but it does suggest pertinent questions. Case studies increase our sensitivity. It is the very specificity of a meticulously studied case that allows us to unravel what remains the same and what changes from one situation to the next.”

Annemarie Mol, The Logic of Care: Health and the problem of patient choice (Routledge, 2006)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Schön’s three responses to the loss of the stable state

In his BBC Reith Lecture in 1970 and in his book Beyond the Stable State in 1971 that followed, Donald Schön confronted the idea of a stable state, the consequences of believing in such a thing, and the responses of the individual when faced with the realization it does not exist.

The responses outlined by Schön to this ontological insecurity seem appropriate given this week’s events in Washington DC.

He begins,

I have believed for as long as I can remember in an afterlife within my own life -- a calm, stable state to be reached after a time of troubles. When I was a child, that afterlife was Being Grown Up. As I have grown older, its content has become more nebulous, but the image of it stubbornly persists.

The afterlife-within-my-life is a form of belief in what I would like to call the Stable State. Belief in the stable state is belief in the unchangeability, the constancy of central aspects of our lives, or belief that we can attain such constancy. Belief in the stable state is wrong and deep in us. We institutionalize it in every social domain. We do this in spite of our talk about change, our acceptance of change and our approval of dynamism. Language about change is for the most part talk about very small change, trivial in relations to a massive unquestioned stability; it appears formidable to its proponents only by a peculiar optic that leads a potato chip company to see a larger bag of potato chips as a new product. Moreover, talk about change is as often as not a substitute for engaging in it.

And then after a few more pages contemplating information overload and the role of technology, he outlines the 3 responses: return, revolt, mindlessness.

The most prevalent responses to the loss of the stable state are anti-responses. They do not confront the challenge directly. They seek instead to deny it, to escape it, or to become oblivious to it. The anti-responses take three primary forms:

Return "Let us return to the last stable state." This is the response of reaction against an intolerable present.

Recently I heard an old farmer in Oklahoma say that he had been farming for forty years and felt he had become something of an expert on the subject. It was his considered opinion that farmers had gone from milking 10 to 20 to 40 cows a day without increasing income, only running to stand still. All this was the fault of the Agricultural Extension Service, and of technological progress in general. Sooner or later we would have to return to the concept of the family farm.

Localism is a special case of return. It is an attempt to enforce and sustain isolation from the phenomena that threaten established institutions and values. Since the cherished past survives in an enclave, the drive to return takes the form of an attempt to protect the integrity of that enclave - as in the State of Mississippi at the present time.

Revolt There is a form of revolutionary response whose war-cry is total rejection of the past and of all vestiges of the past in existing social systems. The characteristic movement of this form of revolt is against established institutions rather than toward a vivid and well-worked-out ideal. In this sense direction comes from the established institutions themselves and the past sneaks in the back door. This form of "reactionary radicalism" moves against, sustains energy only as long as there is a target. It flourishes on the energy generated by the process of revolution itself.

Mindlessness This is an attempt to escape from anguish and uncertainty by evading reflective consciousness itself. The methods may be drugs, hypnotic routine, violence, or a peculiar union with machine technology - like the kids in Midwestern American towns who tool around empty squares at night on motorcycles or in hot rods and seem to be saying, "the Machine is winning. Why not join us?”

The anti-responses share a failure to confront what it might be like to live without the stable state. For them the loss of the stable state is like a gorgon's head, too dreadful to be contemplated. And they are destructive responses. Return is futile; there is nothing to go back to. Revolt, in the form of reactionary radicalism, represents a perverse return under the mask of violence. Mindlessness avoids the dreaded reality only by giving up awareness and humanity.

Constructive responses to the loss of the stable state must confront the phenomenon directly. They must do so at the level of the institution and of the person.

Hard week to confront the phenomenon directly.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

recovering our phronetic awareness

We ended the last chapter discussing how artists attempt to get at and understand the experience of human action as a kind of immersed, purposive engagement with an ever-expanding world; to absorb and document how life would be were it not subject of purely intellectual research. To recover this kind of phronetic awareness, however, is difficult, because it runs counter to our prevailing occidental mindset in social science in which the human relationship with the world is typically understood in detached and linear causal rather than relational terms; it is instrumentally rather than ecologically expressed. [...] ...an understanding of distributed phronesis comes from paying attention to the collective tacit knowledge enabling people to act appropriately and with prudence according to the dictates of the situations in which they find themselves, mindful of, but not slavishly acting in abeyance to, traditions of values and ethics. [...] It is the ability to apprehend why and in what circumstances something can be said to have equipmentality, to be behaving with sufficient reliability, to be good. [...] This is not technical awareness but a value-laden sensitivity of what is right. To extrapolate from one of their examples [...], phronesis is less the technical skill and know-how involved in building a car (technē) than knowing the subjective reasons why that car can be called a good machine [sic]; it is the car understood through its expressive use rather than its technical design. A strategy that is phronetic would similarly occupy a territory of judgement and use value rather than one of engineering facts and proofs; it would look to generate a common good in each situation knowing that this idea of the good can change from one situation to the next as the strategist reads from particular events to general principles and ideal, and back again, in a way that is open, collective and inclusive.

Nonaka and Toyama suggest that what characterizes such phronetic awareness in strategists [...] are: an ability to understand what is in the common as opposed to the individual good in any one situation; the ability to empathize with and accept the legitimacy of other opinions and concerns by being able to read the differing demands of situations; to understand the essence of things and correctly interpret situations by attending to details; the ability to communicate in language that resonates with others; the accrual of organizational power and influence sufficient to be a difference that makes a difference; and the capacity to instill phronesis in others.

Car example from Nonaka and Toyama about what is “good” as a technology notwithstanding, this is a lovely passage.

How do we help others understand the expressive use of technology rather than focus on the technical design, the relational nature of our networked digital tools, rather than linear causal representations that flatten and dull the entanglement through powerpoint decks and visio flowcharts?

from Strategy without Design, Chia & Holt (Cambridge, 2011) pp 134-135

0 notes

Quote

We need to attend to the ways in which the professionalization of Design in the last century has included a legacy of hegemonic claims to adjudicate the question of whose knowledges are relevant to our collective future-making. We might agree to reclaim the keyword design in order to refashion it, but we need to do that deliberately, with an eye to the tensions inherent in articulating projects in transformational change as “small d” design, without reproducing the supremacy of Design with that initial capital letter.

Suchman, Lucy. "Design." Theorizing the Contemporary, Cultural Anthropology website, March 29, 2018. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/1355-design

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

on the neoliberal practice of governmentality...

The implicit logic operating here is that once we are furnished with an explanation, we will be able to act on it in some way. But this places the burden of responsibility on the person the law refers to as the “data subject,” who is required to seek out an explanation, and then exercise prudence in their choices once it’s been provided to them. The right enunciated here is thoroughly consonant with the neoliberal practice of governmentality, which tends to individualize hazards and recast them as issue of personal responsibility or moral failure, rather than structural and systemic issues. It’s a conception of good governance that conflates transparency with accountability: if the information is available, you’re expected to act upon it, and if you don’t, it’s nobody else’s fault but your own. This clearly relies entirely too much on the initiative, the bravery, and the energy of the individual, and fails to account for those situations, and they will be many, in which that individual is not offered any meaningful choice of action.

One of the passages that stood out for me in Adam Greenfield’s Radical Technologies.

1 note

·

View note

Text

So then, what will it take to legitimize prototyping for policy?

Prototyping enables public servants making policy to mediate between actualities and potentialities but is not [yet] a legitimate evidence-producing activity, and is uncomfortable because outside of the normal range of practice. It enables flexibility in policy development, keeping things open as provisional solutions are anticipated, developed or rejected. However, policy solutions are inescapably bound up with ideological and political narratives. By revealing the genealogies shaping prototyping practice, we have shown that its characteristics can be reconfigured inside government within a new spirit of policy-making—yet this may not be able to live up to the hopes associated with such participatory, creative endeavours.

from Lucy Kimbell and Joss Bailey’s new paper Prototyping and the new spirit of policy-making. Lots resonating in this article. Have felt this very real uncomfortable / non-legitimate organizational response to prototyping for policy. And tried to express some of that experience to Joss in London back in March when I had the pleasure of meeting with her.

So the practice isn’t legitimate yet - but what will it take for it land? Likely because as designers, our tendencies (as pointed out in the paper) are felt to “creative, contingent and emergent” while policy types favour the “rational, linear, and reproducible.” Or said another way, the predictable, controllable, and/or causal. Which the public has never and will never be in any policy matter of substance.

0 notes

Text

Users: the people formerly known as the audience

Audience

Originating as a collective noun for those within earshot, who can “audit” a dramatic performance or hear the words of a monarch or pope, the term audience is now used to describe a larger number of individually unidentifiable and mutually anonymous people, usually united by their participation in media use. Given the varying demographics of this group, not to mention variations between nations, the concept itself is a means by which such an essentially unknowable group can be imagined. Naming an audience as such usually also involves homogenizing it, ascribing it to certain characteristics, needs, desires and concerns especially those that a producer-organization is setting out to meet. Thus the audience can be imagined as an agent in its own right. This “knowing” audience is a construction; a discursive abstraction not a natural phenomenon. Beyond the live event where audience members are co-present, it is impossible for “the” media audience to act in concert, and therefore an audience as such cannot want, know, believe, like or oppose anything.

This constructions serves the interest of three “producer” groups:

media organizations; media researchers (including polling agencies and academic critics); regulatory (governmental) bodies.

User

The “user” is a term from computer science that describes the agent on the human side of the human-computer interface; from expert programmer to the end user who runs an application. It has become a very familiar term in ordinary language and a useful concept in the study of media and communication. As a concept “the user” updates that of “the audience” in a transformational way.

Active, not passive. It removes the idea, inherited from mass communication, that the audience is the end point of a chain that leads one way only, from producer, via technology-and-text, to consumer, who is inevitably reduced to passive status with little agency beyond choosing to put their bums on this seat rather than that one and then to get what they’re given. The user is a “sit-up” agent, as well as a “sit-back” one.

Dialogic not one-way. The concept of the user reinstates a two-way model of the communication process, where users are active agents, with their own productivity, who share well as receive mediated content, participating, creating, and publishing their own work.

Turns not divisions: The concept of the user recasts the boundaries between expert and amateur, producer and consumer, cause and effect — it sees these roles as turn-taking possibilities for the same agent, rather than a fixed division of labour between them.

Agent not individual: The user does not have to be a domestic consumer or even an individual. Users can be scientists, entrepreneurs, fashion designers, or what you wil, and they can be firms or affinity groups as well as individuals.

Multiplatform and transmedia: It applies to any computer-related activity, meaning that the same user can be imagined in relation to any media content, including broadcasting (via podcasts for instance). Instead of different audiences (or readerships) following each platform - music, news, TV, cinemas, etc. - content can follow the user.

Thus “the user” changes mediated communication from an industrial to a social-network model, and installs what Jay Rosen dubbed “the people formerly known as the audience” (Rosen, 2006) as the main close of feedback and learning for the open, complex online system, thereby taking their place as agents for the growth of knowledge.

Source: Communication, Cultural and Media Studies; The Key Concepts (Hartley, 2011) Routledge

0 notes

Photo

Sunday at #QueensCX was memorable and forgettable for much the same reason: mud. Had better days for sure. This weekend is looking equally wet. If not more so. Photo Credit: the talented and waterlogged John Denniston. #vcxc #crossishere #cyclocross #mud

0 notes

Text

But we need to try.

Requisite variety is an aspiration, an ideal state rather than something any designer working with human behaviour can honestly claim to offer. But we need to try.

from Dan Lockton: http://requisitevariety.co.uk/what-is-requisite-variety/

1 note

·

View note

Photo

IN CYCLOCROSS, BICYCLE RIDES YOU.

Via: @podiuminsight

352 notes

·

View notes

Video

What a battle. Amazing.

youtube

OMG this is bike racing…

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

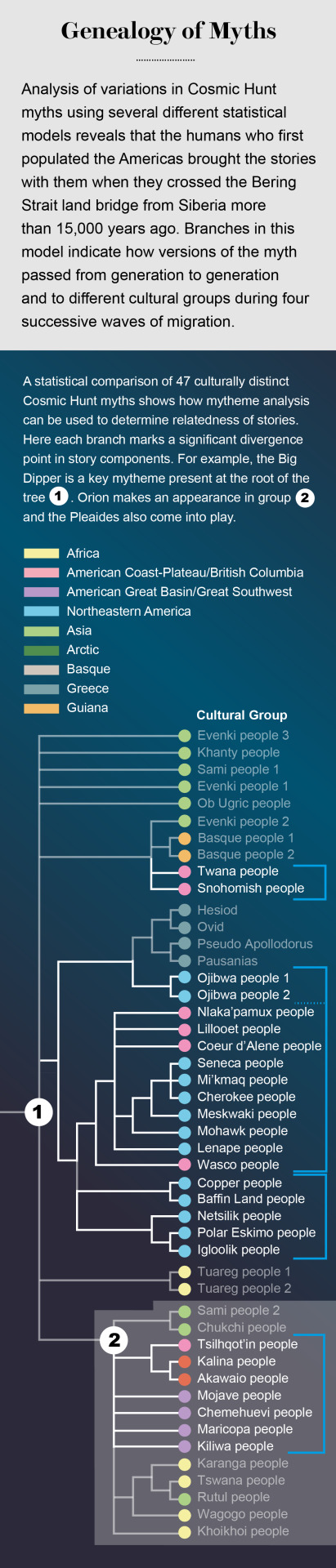

Julien D’Huy, Scientists Trace Society’s Myths to Primordial Origins

Carl Jung, the founding father of analytic psychology, believed that myths appear in similar forms in different cultures because they emerge from an area of the mind called the collective unconscious. “Myths are first and foremost psychic phenomena that reveal the nature of the soul,” Jung argued. But the dissemination of Cosmic Hunt stories around the world cannot be explained by a universal psychic structure. If that were the case, Cosmic Hunt stories would pop up everywhere. Instead they are nearly absent in Indonesia and New Guinea and very rare in Australia but present on both sides of the Bering Strait, which geologic and archaeological evidence indicates was above water between 28,000 and 13,000 B.C. The most credible working hypothesis is that Eurasian ancestors of the first Americans brought the family of myths with them.

To test this hypothesis, I created a phylogenetic model. Biologists use phylogenetic analysis to investigate the evolutionary relationships between species, constructing branching diagrams, or “trees,” that represent relationships of common ancestry based on shared traits. Mythical stories are excellent targets for such analysis because, like biological species, they evolve gradually, with new parts of a core story added and others lost over time as it spreads from region to region.

In 2012 I constructed a skeletal model based on 18 versions of the Cosmic Hunt myth previously collected and published by folklorists and anthropologists. I converted each of those accounts of the myth into discrete story elements, or “mythemes”—a term borrowed from the late French structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. Like genes, mythemes are heritable characteristics of “species” of stories, which pass from one generation to the next and change slowly. Examples of Cosmic Hunt mythemes include: a woman breaks a taboo; a divine person stops a hunter; a god transforms an animal into a constellation. My initial analysis yielded a database of 44 mythemes. For each version of a story, I then coded mythemes as either 1 (present) or 0 (absent) and applied a successive series of statistical algorithms to trace evolutionary patterns and establish family trees. In 2013 I expanded the model to include 47 versions of the story and 93 mythemes. Eventually I used three separate databases to apply different algorithms and cross-check my results.

One of the most up-to-date phylogenetic trees of the Cosmic Hunt [see illustration below] [above in this post] suggests that the family of myths arrived in the Americas at several different points. One branch of the tree connects Greek and Algonquin versions of the myth. Another branch indicates passage through the Bering Strait, which then continued into Eskimo country and to the northeastern Americas, possibly in two different waves. Other branches suggest that some versions of the myth spread later than the others from Asia toward Africa and the Americas.

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

a short description of design

Design is a culture and a practice concerning how things ought to be in order to attain desired functions and meanings. It takes place within open-ended co-design processes in which all the involved actors participate in different ways. It is based on a human capability that everyone can cultivate and which for some - the design experts - becomes a profession. The role of design experts is to trigger and support those open-ended co-design processes, using their design knowledge to conceive and enhance clear-cut, focused design initiatives.

This description must be augmented with one further observation:

In the transition toward a networked and sustainable society, all design is (or should be) a design research activity and should promote sociotechnical experiments.

This transition is a broad, complex social learning process, by which everything that belongs to the mainstream way of thinking and behaving in the world will have to be reinvented: from everyday life to the very idea of well being.

To do this we should look at the whole of society as a huge laboratory of sociotechnical experimentation, which in turn calls for producing and spreading design knowledge able to empower individuals, communities, institutions, and companies in inventing and enhancing original ways of being and doing things. This experimentation phase will last as long as the transition: a short period in the history of humanity but a very long time for us and our children. In practice, this experimental approach will become the “normal” approach in our future.

- Ezio Manzini, Design when Everybody Designs - An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation (MIT PRESS, 2015)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Only suckers (and tourists) ride the stones. The gutter is where it's at...

You want to win Omloop and you aren’t near the front at the bottom of the Taaienberg? Forget about it.

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bauer, Planckert, Van Hooydonck. 1990. Paris Roubaix. So close Mr. Bauer, so close.

11 notes

·

View notes