This blog seeks to explore the world through its people and the diversity of their cultures, art, music, cinema, architecture, philosophies, traditions, beauty standards and lifestyles

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Postcard of Ainu people from Hokkaido, Japan

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Georgian folk fashion. Designed by Samoseli Pirveli.

825 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Workers in a truck cab before work on the man made island of Neft Baslani (Oily Rocks). Photographed by Alex Webb in Baku, Azerbaijan.

885 notes

·

View notes

Photo

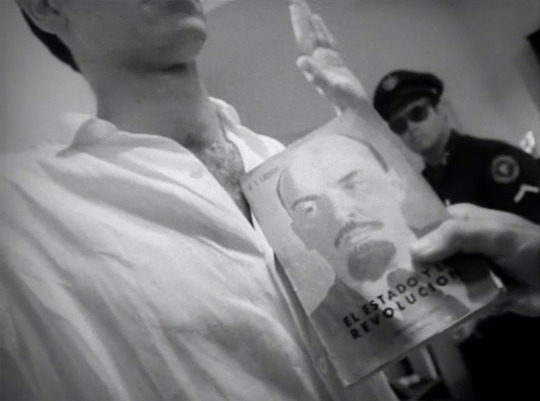

I Am Cuba (Soy Cuba/Я - Куба) | Mikhail Kalatozov | 1964 | USSR

#soviet union#cuba#cubans#mikhail kalatozov#marxist-leninist#communism#socialism#marxist#marxist-leninism#social realism#social realist cinema

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Painted Karo Dancer; Ethiopia - Angela Fisher

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mumbai, India

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Makhachkala, Dagestan, Russia (2008) - Sergey Maximishin

Students during a lecture at an Islamic Theology College

237 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mullets of Medellín - Stefan Ruiz

Stefan Ruiz and Rainbow Nelson venture to Colombia’s Estadio Atanasio Girardotto capture the dedication – and hairstyles – of the fans of Deportivo Independiente Medellín and their more illustrious rivals, Atlético Nacional.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tahiti

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roma Interiors. Photography project by Carlo Gianferro.

“The images of Roma Interiors allow us to enter into the intimacy of the Roma houses in Moldova and Romania, where interiors are represented with its inhabitants in order to solder the connection between the life and the lived. The people, the inhabitants and the owners were photographed quickly, without prior preparation, aesthetic tricks or any special choice of clothes: what you see is what there is, what there was at the time of the shooting, what there is every day.

Women with sumptuous traditional costumes and hairstyles that have remained unchanged over time; men who owing to their dealings outside of their community wear Western clothing; youths wearing the universal fashions of today’s youth everywhere, yet all of these sharing a common background characterized by creativity, color, splendour, and cultural tradition.

Roma Interiors is above all a real and accurate portrait of current Romani society, which is still, as it has always been, based on the family, and the house is the backdrop against which the family is represented. Money and the home are the two main parameters which show the other members of the community the importance and power of the family. In this the Roma don’t deviate from universal motivations, but they articulate it in their homes with an innate and personal expression, with the concepts of luxury, prosperity, and especially power represented by decorative overabundance.

Colours are essential to the Roma people and, as with the women’s costumes, colour covers everything, both the inside and the outside of the houses, making fantastic, unreal buildings - as fantastic and unreal as the dream, the desire of having a house, a stable place for a people that for hundreds of years has roamed far from its place of origin.

Freedom, and the intelligent use of it, has allowed the Roma community to redeem itself in the most obvious and confrontational way possible, using rocks, concrete, iron, wood, plaster, and metal to build these monuments to their desires, and into which they then move to live in a joyous, colourful, world of their own.”

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tibetan New Year, Losar - Hieu Chau

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Armenian bridal attire from the region of Shamakhi, present-day Azerbaijan

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

Masai Men - Christopher Wilson

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mapuche Woman in Temuco, Chile - Marcelo Montecino

470 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dagestan - Luke Duggleby

Located in the North Caucasus, bordering the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan and Chechnya, Dagestan is home to almost 3 million mostly Muslim people. A Republic of Russia it is ethnically very diverse, and made up of several dozen ethnic groups which create Russia’s most heterogeneous republic, where no ethnicity forms a majority.

Dagestan has had a turbulent history and until 2012 was subject to a violent Islamic separatist movement that spilled over from neighbouring Chechnya. Largely subdued by the Russian Government it earned a reputation for being dangerous and violent, a reputation that is compounded by a lack of visitors and up to date news. But there is an overall feeling of being neglected and forgotten and a frustration that its bad reputation still lingers.

Today Dagestan (which means Land of Mountains) is peaceful and remains one of Russia’s untouched treasures. A place where moderate Islam mixes with age-old traditions and due to its relative isolation, this mountainous region has maintained traditional cultural practices that have been lost in many other parts of Russia.

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

Komuso Buddhist - Huseyin Kuchkarov

6 notes

·

View notes