Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

This is the 6th post of a series that explores one of the darkest sections of human behavior, that of mass exterminations. Previous posts dealt with the extermination of the witches in Europe, of young men during WW1, of elderly people, of the rich, of the useless, and now this one about famines as a weapon of mass destruction. From now on, I'll move to different subjects, although I may return to this one, a little depressing, but surely fascinating.

0 notes

Text

The Age of Exterminations (III). Why you Should be Worried. Very Worried

Disclaimer. I am no prophet and I have no crystal ball. I am just trying to find patterns in history. And I think many historical events can be explained simply on the basis of the tendency of people to try to make money whenever possible, even at the cost of doing the most evil things imaginable. That sometimes leads me to making rather somber predictions, as in this post, the 3rd of a series on mass exterminations (part one and part two). Sorry about this, but think that I may well be wrong -- and I hope so!

The extermination of social subgroups is a relatively recent phenomenon in history but, unfortunately, it seems to have become more and more frequent in recent times. Often, as in the case of the witch-hunting age, extermination is the result of a perfectly rational attitude that develops in societies under heavy stress. When a social subgroup is relatively wealthy, can be identified, and can't offer significant military resistance, there are good chances that its members will be exterminated and their assets confiscated. That was what happened to the people branded as "witches" in Europe during the 16th and 17th century in Europe. Another classic case was that of the Jews, a few centuries later.

At this point, considering that our society is surely under heavy stress, the question is: which subgroup could be the next target for extermination? I asked this question to the readers in a previous post of this series, but almost nobody could identify the right target. Now I think I can propose the answer:

The most likely target for the next extermination round are middle-class retirees.

Retirees satisfy all the requirements: They are identifiable, of course, they are old! They are often relatively wealthy and, more than that, they cost a lot of money in terms of health care. Finally, they can hardly put up serious military resistance. Exterminating the middle-class elders would be both easy and profitable.

Let's make a few calculations. In the US, there are nowadays about 46 million retirees living on social security. The US spends about 7% of its GDP on pensions, that is, about 1.5 trillion dollars per year (about $30.000/person/year). That's more than the about 1 trillion dollars that the US government spends for the military budget, bloated as it is.

Assuming that you could remove just 10% of the retirees, it would mean saving some 150 billion dollars per year. But, in practice, much more than that if you take into account the health care costs. For instance, summing nursing care facilities and home care for the elderly, we are talking of something close to 300 billion dollars per year, and that does not include hospitalization costs. The potential savings are truly huge: hundreds of billions of dollars.

Of course, exterminating the elderly cannot be done using the same demonization techniques used in the past against the witches and the Jews. Old people are fathers and grandfathers and their offspring won't normally like to see them burned at the stake or gassed in extermination chambers. But extermination takes many forms, and it is rarely explicitly proclaimed. After all, it never happened in history that you could find a sign with the words "extermination camp" at the gate of an extermination camp. During WWII. for instance, the Germans were told that the Jews were just being relocated, not that they were being exterminated. In other cases, the people being exterminated were glorified as heroes.

So, what form could the extermination of old people take? It would be done using well-known propaganda techniques, the main one being to state the exact opposite of what is being done. In other words, when the idea is to kill some people, propaganda will convince everybody that it is done to do them a favor (do you remember the "humanitarian bombs" dropped on Serbia?)

In practice, the weak spot of the middle-class retirees is that they need medical assistance and that they cannot normally pay the skyrocketing costs on their personal saving. So, they could be gently removed from the state budget by degrading the public health care system while saying that it is being modified in order to protect them. A clever way of doing it would be to focus so much on curing a specific single disease that the result would be a decline of the care for the illnesses that mostly affect aged people: cardiovascular diseases and tumors. A parallel measure to intensify the effect would be to degrade the quality of the food available, making it become less nutritious and contaminated with all sorts of pollutants.This method would not affect the elites, who can pay for good health care and and good food, but it will hit directly those who live on pensions.

Now, let's take a look at the current situation. In 2020 the average life expectancy in the US has declined by nearly 2% for a total of 600,000 extra deaths, most of them old people. So, we are talking of some 20 billion dollars saved just in terms of pensions. But it is much more than that considering the saving in health care costs. These numbers are not large in comparison to the US budget, but not peanuts, either. And what we are seeing is just the start of a trend.

At this point, it is customary to start screaming: "

conspiracy theory!"

It is true that the world is so huge and complicated that it unthinkable to see what happens as the result of a group of evil people collecting, say, in the basement of

Bill Gates' mansion

in Seattle. The mechanism that leads to collective events is collective:

society as a whole is a complex network with a certain ability to process information.

It does that without being "conscious" of what is being done, but often the results are to move society in a specific direction. In this case, Western Society seems to perceive the problem created by an excess of elderly people, and it is moving to solve it. It is brutal, yes, but only individuals have moral restraints, society as a whole has none. Every decision taken individually affects all the other decisions, and we are seeing the results. It is nothing new in history where, typically, everything that happens, happens because it had to happen.

_______________________________________________________________________

This said we have arrived at a worrisome (to say the least) conclusion. Most readers of the "Seneca Effect" blog are middle-class Westerners (maybe Mr. Gates reads my blog? Unlikely but who knows?). And sooner or later we are all going to become middle-class retirees and we are going to experience the ongoing trends. Of course, we are not going to be "exterminated" in the literal sense of the word. That is, no firing squads, gas chambers, or the like. But we will have to live on a progressively poorer diet and we won't have the same kind of health care that our parents and grandparents had.

What can we do about that? The answer is, unfortunately, "very little." Of course, you'll do well in following a healthy lifestyle, exercise, try to avoid the worst kinds of junk food, all that. A sane mistrust in doctors and their unhealthy concoctions may also help a lot. But you have to face it: the life expectancy of the people who are alive today is going to drop like a stone. It will be a classic example of a Seneca Cliff.

But is it so bad? I don't think we should take this as a reason for despair. At least we'll avoid the sad trap of overmedicalization in which so many of our elders fell. When my father was 87, he had a heart attack. I remember that while we were waiting for the ambulance, he said, "I think it is time for me to go." He was not happy, but I think he understood what was happening to him and perhaps he savored the idea of being reunited with his wife, who had died the year before. But that was not to happen. He was kept alive for five more years, every year worse than the previous year, until he was reduced to a vegetal, his mind completely gone, kept alive by tubes and machinery. Being humiliated in that way is not something anyone would desire. When it is time to go it is better to leave this world in peace. If possible, at home.

If you have time, you may do well in reading Lucius Annaeus Seneca's "De Brevitate Vitae" ("on the shortness of life"). Seneca was not so great as a teacher of wisdom and he made some egregiously unwise mistakes (with Queen Boudica, for instance). But when his time came, he died an honorable death. The death of a true stoic.

0 notes

Text

What can we expect for the future when it is clear by now that nobody wants to do anything serious to stop climate change?

As Seneca said, "ruin is rapid" and a further problem is that when you are falling down the Seneca Cliff, you are so busy with surviving that you have no time to look at where the cliff ends: is it on sharp rocks or on a green meadow? Right now, we seem to be more or less at the peak of the Seneca curve and we still have a chance to take a look down and figure out what could happen to us. The result is this post where I examine future scenarios in the assumption that we already passed -- or will soon pass -- the tipping point leading us to a much hotter world. Will humankind survive as a species? Not impossible. Will the ecosystem survive? Almost certainly yes. Will it be a bad world for those who will live in it? We can't say but, as always, Gaia knows best.

https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/2021/08/climate-change-what-is-worst-that-can.html

0 notes

Text

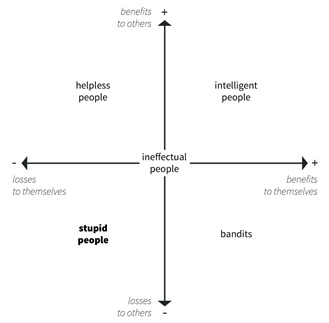

On Human Stupidity

Our study (mine and Ilaria Perissi's) on the root causes of human stupidity. We started from the "laws of stupidity" proposed by Carlo Cipolla and developed a system dynamics model that could explain the laws in a semi-quantitative way. It works. The final result is that humans are stupid because they are too intelligent!

#stupidity #systemdynamics #collapse #overexploitation

https://www.mdpi.com/2079-8954/9/3/57/htm

0 notes

Photo

Excuse me if I return to the Afghanistan story. I don't claim to be an expert in international politics, but if what happened is the result of the actions of "experts", then it is safe to say that it is better to ignore them and it is better to look for our own explanations. And I think that Tolstoy provides one in his book "War and Peace"

#afghanistan #Tolstoy #Napoleon #Taliban

https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/2021/08/lev-tolstoy-about-afghanistan-it.html

0 notes

Text

The Decline of Science

A long post on the decline of Science. Science is dead, long live Science! But in a different form.

https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/2021/08/the-collapse-of-scientism-and-rebirth.html

0 notes

Text

Consensus Building: an art that we are losing. The Case of Climate Science

by Ugo Bardi (from The Seneca Effect”)

In 1956, Arthur C. Clarke wrote "The Forgotten Enemy," a science fiction story that dealt with the return of the ice age (image source). Surely it was not Clarke's best story, but it may have been the first written on that subject by a well-known author. Several other sci-fi authors examined the same theme, but that does not mean that, at that time, there was a scientific consensus on global cooling. It just means that a consensus on global warming was obtained only later, in the 1980s. But which mechanisms were used to obtain this consensus? And why is it that, nowadays, it seems to be impossible to attain consensus on anything? This post is a discussion on this subject that uses climate science as an example.

You may remember how, in 2017, during the Trump presidency, there briefly floated in the media the idea to stage a debate on climate change in the form of a "red team vs. blue team" encounter between orthodox climate scientists and their opponents. Climate scientists were horrified at the idea. They were especially appalled at the military implications of the "red vs. blue" idea that hinted at how the debate could have been organized. From the government side, then, it was quickly realized that in a fair scientific debate their side had no chances. So, the debate never took place and it is good that it didn't. Maybe those who proposed it were well intentioned (or maybe not), but in any case it would have degenerated into a fight and just created confusion.

Yet, the story of that debate that was never held hints at a point that most people understand: the need for consensus. Nothing in our world can be done without some form of consensus and the question of climate change is a good example. Climate scientists tend to claim that such a consensus exists, and they sometimes quantify it as 97% or even 100%. Their opponents claim the opposite.

In a sense, they are both right. A consensus on climate change exists among scientists, but this is not true for the general public. The polls say that a majority of people know something about climate change and agree that something is to be done about it, but that is not the same as an in-depth, informed consensus. Besides, this majority rapidly disappears as soon as it is time to do something that touches someone's wallet. The result is that, for more than 30 years, thousands of the best scientists in the world have been warning humankind of a dire threat approaching, and nothing serious has been done. Only proclaims, greenwashing, and "solutions" that worsen the problem (the "hydrogen-based economy" is a good example).

So, consensus building is a fundamental matter. You can call it a science or see it as another way to define what others call "propaganda." Some reject the very idea as a form of "mind control," or practice it in various methods of rule-based negotiations. It is a fascinating subject that goes to the heart of our existence as human beings in a complex society.

Here, instead of tackling the issue from a general viewpoint, I'll discuss a specific example: that of "global cooling" vs. "global warming," and how a consensus was obtained that warming is the real threat. It is a dispute often said to be proof that no such a thing as consensus exists in climate science.

You surely heard the story of how, just a few decades ago, "global cooling" was the generally accepted scientific view of the future. And how those silly scientists changed their minds, switching to warming, instead. Conversely, you may also have heard that this is a myth and that there never was such a thing as a consensus that Earth was cooling.

As it is always the case, the reality is more complex than politics wants it to be. Global cooling as an early scientific consensus is one of the many legends generated by the discussion about climate change and, like most legends, it is basically false. But it has at least some links with reality. It is an interesting story that tells us a lot about how consensus is obtained in science. But we need to start from the beginning.

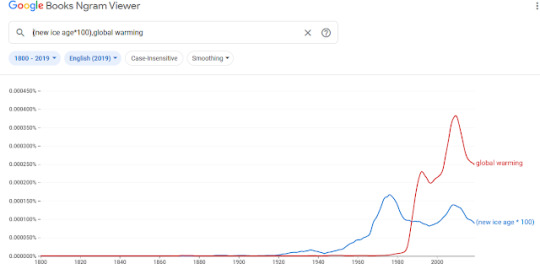

The idea that Earth's climate was not stable emerged in the mid-19th century with the discovery of the past ice ages. At that point, an obvious question was whether ice ages could return in the future. The matter remained at the level of scattered speculations until the mid 20th century, when the concept of "new ice age" appeared in the "memesphere" (the ensemble of human public memes). We can see this evolution using Google "Ngrams," a database that measures the frequency of strings of words in a large corpus of published books (Thanks, Google!!).

You see that the possibility of a "new ice age" entered the public consciousness already in the 1920s, then it grew and reached a peak in the early 1970s. Other strings such as "Earth cooling" and the like give similar results. Note also that the database "English Fiction" generates a large peak for the concept of a "new ice age" at about the same time, in the 1970s. Later on, cooling was completely replaced by the concept of global warming. You can see in the figure below how the crossover arrived in the late 1980s.

Even after it started to decline, the idea of a "new ice age" remained popular and journalists loved presenting it to the public as an imminent threat. For instance, Newsweek printed an article titled "The Cooling World" in 1975, but the concept provided good material for the catastrophic genre in fiction. As late as 2004, it was at the basis of the movie "The Day After Tomorrow."

Does that mean that scientists ever believed that the Earth was cooling? Of course not. There was no consensus on the matter. The status of climate science until the late 1970s simply didn't allow certainties about Earth's future climate.

As an example, in 1972, the well-known report to the Club of Rome, "The Limits to Growth," noted the growing concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere, but it did not state that it would cause warming -- evidently the issue was not yet clear even for scientists engaged in global ecosystem studies. 8 years later, in 1980, the authors of "The Global 2000 Report to the President of the U.S." commissioned by president Carter, already had a much better understanding of the climate effects of greenhouse gases. Nevertheless, they did not rule out global cooling and they discussed it as a plausible scenario.

The Global 2000 Report is especially interesting because it provides some data on the opinion of climate scientists as it was in 1975. 28 experts were interviewed and asked to forecast the average world temperature for the year 2000. The result was no warming or a minimal one of about 0.1 C. In the real world, though, temperatures rose by more than 0.4 C in 2000. Clearly, in 1980, there was not such a thing as a scientific consensus on global warming. On this point, see also the paper by Peterson (2008) which analyzes the scientific literature in the 1970s. A majority of paper was found to favor global warming, but also a significant minority arguing for no temperature changes or for global cooling.

Now we are getting to the truly interesting point of this discussion. The consensus that Earth was warming did not exist before the 1980s, but then it became the norm. How was it obtained?

There are two interpretations floating in the memesphere today. One is that scientists agreed on a global conspiracy to terrorize the public about global warming in order to obtain personal advantages. The other that scientists are cold-blooded data-analyzers and that they did as John Maynard Keynes said, "When I have new data, I change my mind."

Both are legends. The one about the scientific conspiracy is obviously ridiculous, but the second is just as silly. Scientists are human beings and data are not a gospel of truth. Data are always incomplete, affected by uncertainties, and need to be selected. Try to develop Newton's law of universal gravitation without ignoring all the data about falling feathers, paper sheets, and birds, and you'll see what I mean.

In practice, science is a fine-tuned consensus-building machine. It has evolved exactly for the purpose of smoothly absorbing new data in a gradual process that does not lead (normally) to the kind of partisan division that's typical of politics.

Science uses a procedure derived from an ancient method that, in Medieval times was called disputatio and that has its roots in the art of rhetoric of classical times. The idea is to debate issues by having champions of the different theses squaring off against each other and trying to convince an informed audience using the best arguments they can muster. The Medieval disputatio could be very sophisticated and, as an example, I discussed the "Controversy of Valladolid" (1550-51) on the status of the American Indians. Theological disputationes normally failed to harmonize truly incompatible positions, say, convincing Jews to become Christians (it was tried more than once, but you may imagine the results). But sometimes they did lead to good compromises and they kept the confrontation to the verbal level (at least for a while).

In modern science, the rules have changed a little, but the idea remains the same: experts try to convince their opponents using the best arguments they can muster. It is supposed to be a discussion, not a fight. Good manners are to be maintained and the fundamental feature is being able to speak a mutually understandable language. And not just that: the discussants need to agree on some basic tenets of the frame of the discussion. During the Middle Ages, theologians debated in Latin and agreed that the discussion was to be based on the Christian scriptures. Today, scientists debate in English and agree that the discussion is to be based on the scientific method.

In the early times of science, one-to-one debates were used (maybe you remember the famous debate about Darwin's ideas that involved Thomas Huxley and Archbishop Wilberforce in 1860). But, nowadays, that is rare. The debate takes place at scientific conferences and seminars where several scientists participate, gaining or losing "prestige points" depending on how good they are at presenting their views. Occasionally, a presenter, especially a young scientist, may be "grilled" by the audience in a small re-enactment of the coming of age ceremonies of Native Americans. But, most important of all, informal discussions take place all over the conference. These meetings are not supposed to be vacations, they are functional to the face-to-face exchange of ideas. As I said, scientists are human beings and they need to see each other in the face to understand each other. A lot of science is done in cafeterias and over a glass of beer. Possibly, most scientific discoveries start in this kind of informal setting. No one, as far as I know, was ever struck by a ray of light from heaven while watching a power point presentation.

It would be hard to maintain that scientists are more adept at changing their views than Medieval theologians and older scientists tend to stick to old ideas. Sometimes you hear that science advances one funeral at a time; it is not wrong, but surely an exaggeration: scientific views do change even without having to wait for the old guard to die. The debate at a conference can decisively tilt toward one side on the basis of the brilliance of a scientist, the availability of good data, and the overall competence demonstrated.

I can testify that, at least once, I saw someone in the audience rising up after a presentation and say, "Sir, I was of a different opinion until I heard your talk, but now you convinced me. I was wrong and you are right." (and I can tell you that this person was more than 70 years old, good scientists may age gracefully, like wine). In many cases, the conversion is not so sudden and so spectacular, but it does happen. Then, of course, money can do miracles in affecting scientific views but, as long as we stick to climate science, there is not a lot of money involved and corruption among scientists is not widespread as it is in other fields, such as in medical research.

So, we can imagine that in the 1980s the consensus machine worked as it was supposed to do and it led to the general opinion of climate scientists switching from cooling to warming. That was a good thing, but the story didn't end with that. There remained to convince people outside the narrow field of climate science, and that was not obvious.

From the 1990s onward, the disputatio was dedicated to convincing non-climate scientists, that is both scientists working in different fields and intelligent laypersons. There was a serious problem with that: climate science is not a matter for amateurs, it is a field where the Dunning-Kruger effect (people overestimating their competence) may be rampant. Climate scientists found themselves dealing with various kinds of opponents. Typically, elderly scientists who refused to accept new ideas or, sometimes, geologists who saw climate science as invading their turf and resenting that. Occasionally, opponents could score points in the debate by focusing on narrow points that they themselves had not completely understood (for instance, the "tropospheric hot spot" was a fashionable trick). But when the debate involved someone who knew climate science well enough the opponents' destiny was to be easily steamrolled.

These debates went on for at least a decade. You may know the 2009 book by Randy Olson, "Don't be Such a Scientist" that describes this period. Olson surely understood the basic point of debating: you must respect your opponent if you aim at convincing him or her, and the audience, too. It seemed to be working, slowly. Progress was being made and the climate problem was becoming more and more known.

And then, something went wrong. Badly wrong. Scientists suddenly found themselves cast into another kind of debate for which they had no training and little understanding. You see in Google Ngrams how the idea that climate change was a hoax lifted off in the 2000s and became a feature of the memesphere. Note how rapidly it rose: it had a climax in 2009, with the Climategate scandal, but it didn't decline afterward.

It was a completely new way to discuss: not anymore a disputatio. No more rules, no more reciprocal respect, no more a common language. Only slogans and insults. A climate scientist described this kind of debate as like being involved in a "bare-knuckle bar fight." From there onward, the climate issue became politicized and sharply polarized. No progress was made and none is being made, right now.

Why did this happen? In large part, it was because of a professional PR campaign aimed at disparaging climate scientists. We don't know who designed it and paid for it but, surely, there existed (and still exist) industrial lobbies which were bound to lose a lot if decisive action to stop climate change was implemented. Those who had conceived the campaign had an easy time against a group of people who were as naive in terms of communication as they were experts in terms of climate science.

The Climategate story is a good example of the mistakes scientists made. If you read the whole corpus of the thousands of emails released in 2009, nowhere you'll find that the scientists were falsifying the data, were engaged in conspiracies, or tried to obtain personal gains. But they managed to give the impression of being a sectarian clique that refused to accept criticism from their opponents. In scientific terms, they did nothing wrong, but in terms of image, it was a disaster. Another mistake of scientists was to try to steamroll their adversaries claiming a 97% of scientific consensus on human-caused climate change. Even assuming that it is true (it may well be), it backfired, giving once more the impression that climate scientists are self-referential and do not take into account objections of other people.

Let me give you another example of a scientific debate that derailed and become a political one. I already mentioned the 1972 study "The Limits to Growth." It was a scientific study, but the debate that ensued was outside the rules of the scientific debate. A feeding frenzy among sharks would be a better description of how the world's economists got together to shred to pieces the LTG study. The "debate" rapidly spilled over to the mainstream press and the result was a general demonization of the study, accused to have made "wrong predictions," and, in some cases, to be planning the extermination of humankind. (I discuss this story in my 2011 book "The Limits to Growth Revisited.") The interesting (and depressing) thing you can learn from this old debate is that no progress was made in half a century. Approaching the 50th anniversary of the publication, you can find the same criticism republished afresh on Web sites, "wrong predictions", and all the rest.

So, we are stuck. Is there a hope to reverse the situation? Hardly.

The loss of the capability of obtaining a consensus seems to be a feature of our times: debates require a minimum of reciprocal respect to be effective, but that has been lost in the cacophony of the Web. The only form of debate that remains is the vestigial one that sees presidential candidates stiffly exchanging platitudes with each other every four years. But a real debate? No way, it is gone like the disputes among theologians in Middle Ages.

The discussion on climate, just as on all important issues, has moved to the Web, in large part to the social media. And the effect has been devastating on consensus-building. One thing is facing a human being across a table with two glasses of beer on it, another is to see a chunk of text falling from the blue as a comment to your post. This is a recipe for a quarrel, and it works like that every time.

Also, it doesn't help that international scientific meetings and conferences have all but disappeared in a situation that discourages meetings in person. Online meetings turned out to be hours of boredom in which nobody listens to anybody and everyone is happy when it is over. Even if you can still manage to be at an in-person meeting, it doesn't help that your colleague appears to you in the form of a masked bag of dangerous viruses, to be kept at a distance all the time, if possible behind a plexiglass barrier. Not the best way to establish a human relationship.

This is a fundamental problem: if you can't build a consensus by a debate, the only other possibility is to use the political method. It means attaining a majority by means of a vote (and note that in science, like in theology, voting is not considered an acceptable consensus building technique). After the vote, the winning side can force their position on the minority using a combination of propaganda, intimidation, and, sometimes, physical force. An extreme consensus-building technique is the extermination of the opponents. It has been done so often in history that it is hard to think that it will not be done again on a large scale in the future, perhaps not even in a remote one. But, apart from the moral implications, forced consensus is expensive, inefficient, and often it leads to dogmas being established. Then it is impossible to adapt to new data when they arrive.

So, where are we going? Things keep changing all the time; maybe we'll find new ways to attain consensus even online, which implies, at a minimum, not to insult and attack your opponent right from the beginning. As for a common language, after that we switched from Latin to English, we might now switch to "Googlish," a new world language that might perhaps be structured to avoid clashes of absolutes -- perhaps it might just be devoid of expletives, perhaps it may have some specific features that help build consensus. For sure, we need a reform of science that gets rid of the corruption rampant in many fields: money is a kind of consensus, but not the one we want.

Or, maybe, we might develop new rituals. Rituals have always been a powerful way to attain consensus, just think of the Christian mass (the Christian church has not yet realized that it has received a deadly blow from the anti-virus rules). Could rituals be transferred online? Or would we need to meet in person in the forest as the "book people" imagined by Ray Bradbury in his 1953 novel "Fahrenheit 451"? We cannot say. We can only ride the wave of change that, nowadays, seems to have become a true tsunami. Will we float or sink? Who can say? The shore seems to be still far away.

h/t Carlo Cuppini and "moresoma"

0 notes

Text

The Truth About Décolletages: an Epistemic Analysis

This image represents the rape of Cassandra, the Trojan prophetess. It was probably made during the 5th century BCE (Presently at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Napoli, 2422). Note the partial nakedness of the figure of Cassandra: the ancient didn't see female breasts in the same way we do nowadays. Instead of being an erotic symbol, they were seen as a sign of distress. Cassandra's rape scene was almost always represented in this way, but it is not the only example. It is not easy for us to understand why our perception of this anatomic feature of human females has changed so much, but is not impossible to propose reasonable hypotheses. In this post, you'll read about one of these hypotheses from the book "The Empty Sea" (Springer 2020) by Ugo Bardi and Ilaria Perissi. But I'll start with some epistemological considerations.

Science is supposed to tell us what things really are. But is it true? In recent times, the prestige of science seems to be declining for various good reasons. An example: in his "Red Earth, White Lies," Vine Deloria, Jr. starts with a citation from the 1973 series by Jacob Bronowski, "The Ascent of Man."

"Why are the Lapps white? Man began with a dark skin; the sunlight makes vitamin D . . . in the North, man needs to let in all the sunlight there is to make enough vitamin D and natural selection therefore favoured those with whiter skins."

Deloria notes that "Lapps may have whiter skins than Africans, but they do not run around naked to absorb the sunlight's vitamin D." From this, he says that "my faith in science decreased geometrically over the years."

As a first reaction, Deloria's position is understandable. How could it be that a renowned author such as Jacob Bronowski (1908 –1974) uttered such a silly statement? But, as always, things are more nuanced than they seem to be. It is true that Bronowski was somewhat careless, but it is also true that Deloria played a typical game of rhetoric by using a single sentence out of context.

Read the whole paragraph and you'll see that Bronowski did NOT say that the Lapps are white because they live in the North. He was just comparing the time scales of cultural and genetic adaptations, noting that the Sami (once called "Lapps") maintained a skin color that they had inherited long before from their remote ancestors. When they migrated to their current lands, the Sami didn't need to expose their skin to the Sun simply because their traditional diet included plenty of fish and that provided them with abundant vitamin D. (of course, nowadays they may well subsist on fast food, but it is another story)

But Deloria's position should not be banalized, either. True, his chapter on "Evolutionary Prejudice" is mainly a series of statements of disbelief. But, if he takes this position, there has to be a reason and the reason is that science often does not hold up to the lofty promises made to everyone. Not rarely, we are presented with a kind of science that cannot be discussed, doubted, or criticized just because it is "Science" with a capital letter.

The problem is that science has been badly banalized, bowdlerized, politicized, financialized, and more. With scientists nowadays selling themselves cheap to whoever wants to buy them, it is hard to discount Deloria's position. Like him, I am starting to distrust scientists.

But I still believe in "science." Science is, in the end, a set of epistemic tools. It is up to us to use them well, not as an excuse to disparage the wisdom of our ancestors. Science has little to do with the TV utterances of pompous scientists. It is not represented by the inflated claims of the newest trick that, maybe, will solve this or that problem. It is not about the silly power games that academics play, those who pretend to teach our young how to behave. It does not tell us to do things we feel are wrong to do and, if it does, then it is wrong science.

True science, as the name says, is about knowledge, and knowledge is never fixed, never complete, never written in stone. Like the universe, knowledge changes all the time, and change is what we need to learn to appreciate. Science doesn't give us absolute truths. But it does tell us something about the infinite variety of the way the universe works and its beauty -- ultimately a homage to the Goddess of Earth, Gaia. This is the kind of science we can trust.

About the specific issue that Deloria and Bronowski raised, the color of the human skin, I do think that there is a lot of merit in the scientific explanation that attributes it to the fact that humans need to be exposed to the sun to synthesize vitamin D inside their bodies. It is a fascinating story that deserves to be learned as part of the human adventure that started tens of thousands of years ago, and that is still ongoing.

On this matter, I and my colleague Ilaria Perissi even played with the hypothesis that the need for vitamin D was the ultimate reason for the fashion of woman décolletage that started in Europe with the waning of the Middle Ages.

We discussed this matter in our recent book "The Empty Sea." It is a book that deals mainly with the economics of marine resources and, in exploring this subject, we found plenty of unexpected facets of how differently humans behave (you may also be interested in a short theater performance by the authors!). I am presenting to you an excerpt from the book that I hope you'll enjoy. Don't take it as the absolute truth: it is just a possible facet of it. And we continue learning!

From "The Empty Sea," by Ugo Bardi and Ilaria Perissi, Springer 2020.

Here, we are going to propose to you the hypothesis that the fashion of women’s décolletage is related to fishing. No, it is not because human females copied the fashion of going around topless from mermaids! It is a more complicated story of interrelationships in human culture and society, one of those relationships that often lead to unexpected consequences. But let us start from the beginning.

Figure 14 – Roman statuary piece, probably representing Thusnelda, the wife of the German leader Arminius. It is presently at the Loggia de’ Lanzi in Florence, Italy.

As we all know, female breasts are something very popular with human males, nowadays. But that may not be the same in all cultures and, in particular, it was not the same in the past. It would be a long story to tell, but let us just note that, in classical times, when you saw the breasts of a woman exposed in a piece of statuary or in a painting, it did not signal sexual attraction but distress. You can see that well in the picture of a Roman statuary piece, presently in Florence, that may go back to the 1st century CE. It is said to represent Thusnelda, the wife of the German leader Arminius who had defeated the Romans at Teutoburg in 9 CE. Later on, the Romans managed to capture Thusnelda and they were obviously happy that they could show her sad and distressed as a war prisoner.

We find little trace of erotic interest in female breasts in European art until the late Middle Ages, when the fashion for women of flaunting their cleavage at men started. It was the origin of the fascination with breasts -- we could say “fixation” -- typical of our times. But, if something exists, there must be a reason for it to exist. What caused this cultural change to appear and spread?

To find the explanation, we can go back to the times of the fall of the Roman Empire, around the 5th century AD. When the empire collapsed, the center of gravity of the population of the Western tip of Eurasia shifted northward. It was a slow process that saw northern Europe change from a land of sparse and nomadic populations to a highly populated and urbanized area. Of course, this large population had to be fed and, in earlier times, fish represented a fundamental element of the diet of northern Europeans. But fishing could not keep pace with the growing population. Not only the amount that could be produced was limited, but there were no refrigeration technologies that could have allowed the distribution of fresh fish inland. So, from the Late Middle Ages, northern Europeans relied mostly on agricultural products for their diet: grain, barley, wheat, and the like.

At this point, there arose a problem with the new diet: it was poor in vitamin D. Humans badly need this vitamin, lacking it leads to rickets: weak bones, and other related illnesses. But the human metabolism is unable to synthesize vitamin D by itself, so humans can obtain it in two ways: from food that contains it, typically fish, or from a chemical reaction that takes place in the human skin when exposed to ultraviolet radiation from the sun.

Now you see the problem with getting enough vitamin D in northern Europe: not enough sun. It was probably the same problem that led our remote Cro-Magnon ancestors, originally dark-skinned, to acquire a pale skin when they migrated to Europe from Africa, some 40,000 years ago. Pale skin is more easily penetrated by ultraviolet radiation and that helps to make more vitamin D. But, during the Middle Ages, northern Europeans could not get paler than they already were, and if they ate a diet poor in fish, it is certain that they didn’t have enough vitamin D. Data are lacking for ancient times, but rickets has been an endemic disease in northern Europe up to relatively recent times.

A way to get more vitamin D is to expose a larger fraction of one’s skin to the sun. Indeed, you may have noticed how modern Northern Europeans apply this tactic in summer when they tend to stay in the sun as much as they can, while rather scantily clad. But, during the Middle Ages, dress codes were tighter than they are nowadays. For men, then as now, there was no problem with wearing shorts or going shirtless. But for women it was more difficult: baring one’s legs was considered sinful beyond the pale, to say nothing about going topless. What women could do, though, was to bare a part of their skin that was not considered too sinful for males to behold: their necks and shoulders.

Note that during the Middle Ages nobody had the scantest idea of what vitamin D could be and of its relationship with sunlight and human skin. Just like our Cro-Magnon ancestors had not planned to get pale skins, the diffusion of décolletages was probably a question of trial and error. With the vagaries of fashion, women who exposed more of their skin to the sun had a better supply of vitamin D. They were healthier and they were imitated.

It was the start of the fashion of the low neckline that was gradually lowered more and more until it arrived to show part of a woman’s cleavage. We see this fashion expanding in European art from that period. In the figure, you see an example in a miniature made by the Italian painter Giovanni di Benedetto da Como in 1380. Note how splendidly dressed these ladies are, they are true fashion models. And note their ample décolletages. It was a brand-new fashion for those times that is lasting to this day, the origin of our modern fascination with a specific part of the human female anatomy.

Of course, we are presenting to you just a hypothesis: we have no quantitative data on the incidence of rickets in the late Middle Ages, nor statistical data on the benefits of décolletage at that time. But, from what we know about vitamin D and human health, décolletages must have helped the people of Northern Europe of that time and so we believe that the fisherman’s curse is a possible explanation for the diffusion of décolletage in Europe. We leave it to our readers to decide how likely it is that this is a correct explanation.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Empires are typical examples of the Seneca Curve. They grow slowly, then collapse rapidly. But, between the growth phase and the declining one, sometimes there is a period of relative peace, a twilight, when the Empire stops engaging in military adventures and concentrates on mere survival. That happened for the Roman Empire, which enjoyed a "Pax Romana" at the time of the Antonine dynasty from AD 96 to 192. For the current Global Empire (aka the American Empire) we may be entering a similar phase, as indicated by the abandoning of Afghanistan. Things are much faster nowadays than in Roman times, so it is hard to think that the Pax Americana will last a century

https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/2021/07/the-twilight-of-global-empire.html

0 notes

Photo

This summer, we'll be working at promoting our (mine and Ilaria Perissi's) book "The Empty Sea."

This book is a travel in learning about the still mysterious landscape on Earth: the sea. The authors narrate the great journey of human beings: from the discovery of the sea by our remote ancestors to the modern trends of overexploitation. In this travel, you find gems of knowledge that you can't find anywhere else: How did Neanderthals sail on the sea? What did the Sea God tell to ancient fishermen? What did the apostles fish in the sea of Galilee? How could a few men on a small boat kill a giant whale? Who invented frozen fish sticks? How is the modern fashion of women's decolletage related to fishing? And much, much more. (image background, courtesy of "Pescheria Barabino, Firenze).

https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030518974

#blueeconomy #emptysea

0 notes

Photo

The latest post on "The Seneca Effect:" A discussion on how science seems to be taking the same road as older belief systems did when they became incompatible with the society in which they existed. Just as Paganism was replaced by Christianity, which then was replaced by Science, which, in turn, will be replaced by something else. It is time for a big paradigm shift.Yet, old beliefs are replaced only after a phase of desperate efforts of the believers to keep them alive. By now, the belief system we call "science" is obsolete for several reasons, especially in the sclerotic form called "scientism." But it still enjoys a certain prestige and desperate efforts are ongoing to keep it alive.A characteristic of this phase is that the supporters of an obsolete system seem to lose faith in the deities that they are supposed to adore. The result is widespread corruption, one of the many problems of science.

https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/2021/07/the-collapse-of-science-why-we-need-new.html

0 notes

Photo

Who rules the world? The question is equivalent to understanding how the world's network of relations is organized over what is now the human memesphere: the Internet. In this post, I argue that the wars for the domination of the Internet are over. Google won and is now the new World Emperor, ruling by means of epistemic dominance. The post also honors the good king of Hawai'i, Kamehameha 1st.

https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/2021/07/who-is-emperor-of-world-new-age-of.html

0 notes

Photo

What could bring down the industrial civilization? Would it be global warming (fire) or resource depletion (ice)? At present, it may well be that depletion is hitting us faster. But, in the long run, global warming may hit us much harder. Maybe the fall of our civilization will be Fire AND ice.

#climatechange #peakoil #collapse

https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/2021/07/climate-change-and-resource-depletion.html

0 notes

Photo

https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/2021/06/dust-thou-art-and-unto-dust-shalt-thou.html

0 notes

Photo

This post is contributed by a commenter of "The Seneca Effect" who signs it as "Rutilius Namatianu.s. It is the first of a series of three posts that re-examine the four scenarios proposed by David Holmgren in 2009 in terms of a "quadrant" that separated the various effects of climate change and resource depletion. It is an interesting story and I am sure you'll find much food for thought in reviewing those old predictions which (unfortunately) seem to have been prophetic in several respects. We seem to be living in a world dominated by madness, but in that madness, there is some method.

https://thesenecaeffect.blogspot.com/2021/06/four-scenarios-for-future-part-one.html

0 notes