The Art, Craft and Technology of Mixing for Interactive Media.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Link

Here is a really worthwhile deep-dive video diary documentary into the mix of a AAA video game and how it all comes together with the thought process and practicalities involved.

The game sounds astonishing, and the mix has such an enormous amount to do with that.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Optimizing the Aural Experience - an adaptive loudness approach for Android from Netflix. #GameAudio can learn a lot here, especially for mobile devices.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Steinberg has posted a very nice walkthrough of their ‘in the box’ Atmos mix and render pipeline for Nuendo 11. The site provides the basic overview along with video content to show how it is all achieved.

0 notes

Link

More juicy info here from Netflix describing their mixing specifications and prerequisites for mixing facilities. As we in game audio keep our eye on shifting loudness and mix developments in streaming home entertainment, it is important to understand that in game sound, we compete and are compared directly with streaming linear content in terms of mix levels in the home theatre and consumer domain.

0 notes

Link

This is a fabulous introductory article on mixing and mastering Atmos for Home Theatre. It gives a good overview of the different flows for objects and beds, and also provides links at the bottom of the piece to other resources from Dolby for the RMU. While perhaps not relevant for game audio workflows, other than pre-rendered cinematics, it is still interesting if you are set up in your studio to support film/steaming formats as well as game audio spatial sound.

0 notes

Text

All in the Mix: Forza Horizon 4

‘All in the Mix’ is a series of interviews with leading practitioners in the video games industry who are pushing the boundaries of interactive mixing. In the second in the series, Fraser Strachan, Senior Audio Designer, from Playground Games talks with Rob Bridgett about the opportunities and challenges of mixing this incredible title.

RB: First up, Fraser, thank you for taking time out to chat about the mix of the game! Can you start by talking about the overall philosophy of the mix for Forza Horizon 4. Did you plan in advance anything you wanted to achieve with the mix specifically?

FS: The mixes for Forza Horizon games are always complex and every game presents new challenges. More than most games, we battle with constant full frequency sources clashing with one another. Our overall mix philosophy is governed by the Horizon Festival being both a music and car festival. Music and cars are just as important as one another, so there is a delicate balance between the two. It's worth noting that the Forza Horizon 4 mix also has to serve multiple purposes. It has to be exciting, bold, and energetic during what we call our "Initial Experience", whilst providing a lean back experience for those that continue to play the game for hundreds of hours. We want people to be on the edge of their seats sometimes, but we also don't want the game to sound fatiguing for those long play sessions with friends. To that end, we plan in advance for multiple mix states throughout the game such as our initial drive, freeroam, and races to help us meet these goals.

Something that we always plan for in advance is mix consistency. When you have hundreds of music tracks and over 500 cars, the mastering process alone can take several months. We always schedule plenty of time to ensure that no matter what radio station, and no matter what car, you will always roughly have the same mix experience.

One of the biggest things I had to consider with the mix for Forza Horizon 4 was having to mix for an existing franchise. Having already released 3 games in the series you start to set people’s expectations. Once players learn how to interact with your game using certain sound cues or mix levels, it can be hard to break away from those standards. I spent a lot of time researching our previous mixes to ensure that I was remaining faithful to the franchise.

RB: The spatialization and sense of play with music is something that I really loved in the game (diegetic to non-diegetic and back again). Can you talk about how important that was and if there were any challenges with working with music spatially?

FS: It's really important to us to try and ground the radio stations in the game as part of the world. We want players to hear the connection with the Horizon festival. We also want to ensure that the player gets to listen to the music that they chose to listen to. Rather than crossfade between the radio stations and some pre-baked festival music as you drive through, we crossfade between a spatialised version of your radio coming out of the speaker stacks. Our classical music station posed a slight challenge for the system because it doesn't make sense for the festival to be blaring out classical tracks. For this, we have to create switches that force the music to be 2D if you are on that station.

The main challenge of the 3D music system is getting the blending between 3D and 2D right whilst maintaining audibility. Crossfading between surround sound and a mono point source version with a smaller spread can cause volume balancing issues. Combined with the festival EQ treatment, you can easily create dead zones as you drive through the festival. We went through a lot of iteration passes to get the placement of 3D music emitters just right.

[Above: Forza Horizon 4: Radio Stations]

Our 3D music system adds interest throughout the world too and brings the festival vibe into races as you drive around the circuits. I actually flipped our 3D music philosophy for Forza Horizon 4 due to the introduction of our "Whitespace" loading screens. On Horizon 3 we would have 3D music in our pre- and post-race screens with 2D music during races. However, our ethereal whitespace leant itself to 2D music which allowed us to use 3D music during races.

RB: For your day to day process of implementing and crafting the sound for the game, can you go into a bit more detail of the day to day processes for mixing, for example, did you have a specific approach to mix portions of the game when they were complete, or did you pre-mix constantly as you went?

FS: We try to pre-mix as much as possible even during our initial implementation passes. Each system is never really handed off to be mixed, the mix passes just touch on areas that need tweaking. Pre-mixing as we go requires the audio designers to have a point of reference, therefore during production I try to establish a set of sounds which can be used to contextualise everything else. These are usually a handful of car engines with varying frequency content and a couple of music tracks. Those music tracks then become the mastering tracks and we try to slave everything to them.

When we hit mid-production I would start to do intentional mix passes every week where possible. These would normally see me combing through systems looking at gain structure and adjusting things at the lowest level possible. I try not to touch the mixer levels at all until the game is being finalised. For instance, I've seen problems in the past where an early decision is made to turn a mixer fader down by -10db and that results in audio designers cranking their sounds down at the lower levels which can cause all sorts of headaches.

In general, I try to chat to the audio designers about why I might change something in their system before I do it to instil our mix philosophies for future reference.

RB: In terms of sound options (in the user options menu) do you have a particular philosophy there where you give a lot of control over the mix to the player for getting the best kind of experience for them?

FS: Our main philosophy with regards to the sound options is to allow the player to play the game the way they want to play it. I feel that the mix allows for good all-round gameplay which is our "default mix" but some players might want to hear more of their tyres to give them a competitive advantage. Other players might just like their car engine to be a touch louder than the music if that is their preference. It's our way of giving mix clarity to those that have different priorities depending on their needs. Likewise, giving players the ability to completely turn off the DJ's voice or SAT NAV is important to us. It's a very subjective part of the experience that may otherwise cause them to turn the volume down completely. However, we don't allow the player to turn any one system down completely as it can really unbalance the mix.

RB: Obviously the feel, excitement and impact of driving these cars at incredible speed comes across incredibly well in the way the game sounds, often in a visceral way... Can you talk a bit about how you manage the dynamics of sound for the game - and by this i'm thinking more of the narrative dynamics of the race and the pressure of other cars approaching etc, there is a narrative element to the sound that I don't get from other racing titles..

FS: There are a few dynamic mix techniques we use throughout every race both to provide mix clarity and to give the player the feedback they need to race as best they can. To begin with, we have a different mix state at the beginning of races which lasts throughout the countdown and slowly blends into a race mix over about 10 seconds. This "pre-race" mix state amps everything up by pulling back incidental sounds and placing the main focus on the music and your engine. We force the music to be 2D in this state so that it plays a narrative non-diegetic role. The start and end of our races are also punctuated by hitting pre-specified music drops which really bookend the experience.

Broadly speaking, our "race" mix puts more of a focus on the cars and the surface audio to allow the player to hear when they need to change gear or when they may be losing traction with the ground. We utilise a "pack density" parameter to determine how busy the area is around the player. The mix can become cluttered when there are half a dozen loud engines surrounding the player so this allows us to create some space. Conversely, if the player is out at the front of the pack then we can change the mix of remote players based on density, direction and distance to allow the player to hear someone approaching from the rear and give them enough time to react.

RB: Do the differing environmental/weather changes or other events kick in at scripted moments to add excitement, variety or change the mood etc?

FS: Seasons are a massive part of Forza Horizon 4, changing the entire landscape for players every week. Not only do seasons change the visuals of the game but they also change every part of the audio experience. We want the players to hear seasonal variations of a single race. The first dirt race the player comes across is in Summer and features hard surfaces with dry gravel. The player is then taken back the same race in Autumn where large puddles have formed and patches of wet squelchy mud cover the track. Seasons also bring with them unique weather conditions which can be scripted at different points of the races. Snow storms feature in Winter and rainy showers can come and go in Spring. We need to listen to and account for all of these weather conditions in the mix as the players can also create blueprint races where they can choose all of these conditions for themselves. Lightning storms were featured heavily in our first expansion pack "Fortune Island" which allowed us to play huge lightning strikes at certain points and these came with loud spatialised crashes.

RB: The Delta-Wing showcase was such an amazing opportunity to showcase the ATMOS overheads - I recall Andy Vaughn from Dolby telling me about this race with a jet-plane and I was blown away by that idea - even before playing it - this feels like a concept that was very much inspired by having the overhead spatial sound to play with? Is that how it was conceived?

FS: Showcase races have become synonymous with the Horizon series and we always push to make audio a huge part of these experiences. The showcase races are a fantastic opportunity for us to implement Atmos moments as the camera is predominantly looking forward rather than up at the object making the sound. The Delta-wing, Halo, Flying Scotsman and Dirt Bike showcases were all perfect as the vehicles can all travel overhead.

[Above: Deltawing Showcase Race]

We knew that we were going to be implementing spatial audio long before anyone had decided upon the showcase vehicles so the ability for Atmos moments played a huge part in the vehicle criteria. This was only possible by the audio department getting involved in the design process from the offset. We also worked with the level designers early on to ensure that the vehicles always went directly above the car at least once in each of the races. In reality, by the time they were finished, there were around 4-5 Atmos moments in each race.

Another large Atmos moment for us is the Forzathon Live airship which shows up at a random location in the world on the hour. The sound of this is featured in the height channels alongside blaring 3D music as a beacon for players to follow.

RB: Do you have anything approaching what could be called a final mix phase in your audio production? Do you take the game anywhere different outside of the dev space to mix it?

FS: We are always working on other systems, bugs and finishing touches towards the shutdown of our games so we don't have a dedicated period of time where we only work on the mix. However, we do have intensive weekly mixing sessions with our game directors in the final couple of months. We are fortunate that our studio directors have keen ears and feel really passionate about making our games sound the best they can be. They will give as much time as they can to review mix changes in the final weeks.

We mix our game in multiple spaces around the studio in various configurations (7.1.4, 7.1, sound bars, headphones and TV speakers). Perhaps the most important listening experience is a consumer home environment as it is one of the most common endpoints. It's also the way I consume most of the media that I watch and play so my ears are well tuned into those types of devices.

I tried not to mix every day if possible so that I could return to the overall mix experience having left my last changes to settle a bit. Otherwise I think I’d easily get lost in the changes and loose a frame of reference.

RB: Finally, on the tech side of things can you tell me a little about the live tuning process of mixing the sounds in the engine? Are there any special mix features or techniques you can share?

FS: We probably use snapshots in FMOD Studio far more extensively than they were really intended for. On the one hand we have global mixes and on the other we can have hundreds of individual states for unique cinematics in our game. Sections of gameplay have their own attributed snapshot mixes too. This allows modular gameplay pieces such as our "Danger Sign" jumps to play at any time and still affect the mix in a predictable way. To allow shared global states, a variable attack and release system was also created for our global snapshot mixes which mean they can be configured by designers depending on the situation.

As you can imagine, with so many interchangeable mix states, we have to ensure that their priorities have been set up correctly using groups and hierarchies within middleware. One of the new features added to FMOD Studio recently was the ability to see what the combined fader values are when multiple snapshots are active. This is useful to make sure that nothing is being attenuated more than intended.

Another mix technique that I find extremely useful was to utilise our in-game replay system. This was incredibly handy when mixing races or showcases. It allowed me to play a race once and then infinitely loop the same section of gameplay to listen to mix changes.

RB: Thanks again to Fraser Strachan for this super in-depth interview, and congratulations to the whole team at Playground for delivering on this incredible experience.

Forza Horizon 4 is available now on Xbox One and Windows

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Worth another listen. Successful Spatial / Immersive sound needs to be ‘designed’ into the scenes.

0 notes

Text

All in the Mix : The Division 2

‘All in the Mix’ is a series of interviews with leading practitioners in the video games industry who are pushing the boundaries of interactive mixing. In the very first of the series, Massive Entertainment's Audio Director Simon Koudriavtsev (pictured above) chats with Rob Bridgett about The Division 2.

Tom Clancy's The Division 2 is a shooter RPG with campaign, co-op, and PvP modes that offers more variety in missions and challenges, new progression systems with unique twists and surprises, and fresh innovations that offer new ways to play.

RB: Hey Simon, firstly, thanks so much for taking time to chat about the mix! Can you talk a little bit about the overall philosophy of the mix of sounds, music and voice in the game.

SK: I wanted us to create an immersive, detailed, engaging mix, highlighting the player actions, our RPG elements and one which catered to both longer playtimes and co-op play. Since we have so many different game-modes, we had to do specific mix-states for each one, on top of this we utilised the Wwise HDR system to reduce clutter, and to add more punch to the most important elements. In terms of routing we always had to consider 3 perspectives, the player, other players, and NPCs.

RB: Something I’m always curious about, especially with shooters is perspective - was there a ‘naturalistic’ approach or a more stylised character ‘POV’ approach?

SK: I’d say it was more naturalistic, given the 3rd person perspective and the “grounded in reality” direction we were given for the game as a whole. Most of the inspiration for improving the mix came from having done the 1st game, and our own internal post-mortems, as well as the feedback from the community. We wanted to improve on most aspects, mix included.

RB: How do you get around mixing when things like lighting and camera can potentially still be changing?

SK: In our type of game we rarely had this issue as we never take away control from the player. The only time that happens is in cut-scenes, for which we used in-game ambience, and a pre-baked Foley track, so camera angles weren't really an issue.

RB: Something we hear discussed a lot in mixes are dialogue levels- Is dialogue king here?

SK: Not always. For critical mission vo and cutscenes yes, in normal gameplay the player weapons & skills play a bigger part mix-wise. I wouldn’t say that we mixed it all around Voice.

RB: How did you approach the day to day dev process of mixing the game, obviously the gameplay is super dynamic and there are a variety of situations that can occur in almost any location – how did your team tackle new features etc?

SK: We mix the game as we go, the sound-designers are responsible for putting in assets in accordance with the loudness / routing guidelines I set up, and then we tweak as we go. Throughout the production of the game I asked the team to consider the mix when working on any new feature, so there was always a sort of pre-mix done on a lower level. This meant that when we finally had our mix days at Pinewood, we could focus on the bigger picture, and not get into micro-managing things too much.

youtube

(Tom Clancy’s The Division 2: Behind the Scenes | The Sound of The Division 2)

RB: You’ve mentioned you did your final mix pass at Pinewood- can you talk a little about how you decided to mix there?

SK: There wasn’t a lot of time at the end to do a full mix on such a huge game, so constantly thinking about it during development, was the only way. In the end we only had 5 days ! As for deciding where to do it, we needed a calibrated Atmos mixing setup, and since we’ve been working closely with Pinewood UK on this project, it was a very natural fit to do it there.

(above: The Final Mix team at work, Pinewood, UK)

Prior to departing to the mix stage, we all played the game for a few days locally, and made lists of things we wanted to address, so we had a tentative plan going in, but when we heard the game in that environment for the first time, it revealed all sorts of issues we hadn’t noticed before, so we had to re-adjust. We played as many varied scenarios as possible, on as many different setups as we could and what initially felt like a chaotic “let’s fix this, or no, let’s fix that first” process, eventually crystallised into a shared mindset between myself and the team, it was quite an organic process, that’s tough to put into words… We spent a lot of time on balancing the player and NPC weapons, and bringing forward the details of our world. I’m super happy about how it all played out in the end.

RB: I definitely relate to the organic process you describe. For Atmos specifically, what are the things that jumped out in terms of opportunities to use the overheads?

SK: A few things. For weapons we have a “slapback” system that places emitters onto building geometry, providing unique gun-reflections depending on where the player fires the weapon. For us, these are usually somewhat skewed towards the overheads. Another thing that was a nice fit was weather sounds, thunder in particular, or the sound of the rain hitting the props above the player. Also, any thing that flies above you (helicopters, drones) is cool to highlight in the overheads.

(above: monitoring in Dolby Atmos at Pinewood, UK)

RB: Those are awesome details to listen out for! Could you talk a little about the busses and routing you developed for handling the mix at run-time?

SK: We had quite a complex bus system, with both HDR and non-HDR elements. The HDR system was reserved for big elements like ambience, guns, explosions, voice and music, whilst the non-HDR bus was used for less critical sounds. On top of this we also had 2 master buses, one that was running everything spatial, and another non-spatial through which we routed things like front-end elements and cutscenes. Then depending on which game-mode we were in, we had different mix-states applied to the appropriate sub-buses.

RB: Finally, any surprising pleasant (or otherwise) side effects that happened right at the end of the process of mixing that you were able to capitalise on? And what’s next?

SK: I think mixing "as you go" was crucial for us, so was also setting up the loudness guidelines from the beginning. One thing we found towards the end is that the master compressor and limiters where hiding a lot of issues. So when we went in to the mix we removed all of that, and found a good balance, and only applied it again gently towards the end of the mix. We also added a TV Speaker mode with a bit less dynamic range, and a Headphones mode, with a bit more dynamic range.

(above: Massive Entertainment: Malmö Sweden.)

We have quite an ambitious post-launch plan, so we are constantly facing new challenges (8 player raid is one of them 🙂) so the mix develops together with the game, but i'm very happy with the base level we reached at launch.

RB: Thanks again Simon for taking us through some of the details of your mix approach and process. And congratulations to you and your team, the game sounds fantastic!

The Division 2 is available now on Xbox One, PS4 and PC.

0 notes

Text

Final Loudness-Tweaking

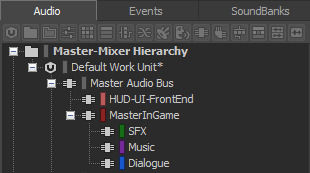

Here is a quick planning / organisation tip for setting up a bus structure in which you have control over ‘overall loudness’ of all of your in-game sound mix, while preserving the fixed levels of the sounds that live ‘outside’ of the in-game sound world.

Separating your menu and in-game UI sounds from the rest of the in-game sounds in your game allows you separation and independent control of overall levels during a final balancing pass when paying particular attention to ‘loudness’ measurements.

In this example image below, you can see that underneath the Master Audio Bus, there are two parent busses. The HUD/UI bus, which contains all ‘fixed level’ sound in the game, and the ‘MasterInGame’ bus, which is the NEW master bus for every sound that actually occurs ‘in-game’. The important thdifference here is that the UI sound is not a bus underneath the Master In-Game Sound bus, inheriting whatever happens to that bus - which is usual in most hierarchical approaches we see. It is its own master bus.

I’ve found that in the very final passes of a mix when you already have the sound really well balanced, but just need to attenuate the overall levels up or down by a few dB to hit a healthy loudness (LUFS) measurement range, that you need to push all the relative volumes up or down at some kind of master level, and preserve the complex interrelationships of the mix of everything underneath. This is especially useful if you are in your mix and inheriting maps made and premixed by many different sound implementers, for example, who monitor at slightly different levels in different rooms.

Doing this kind of global dynamic adjustment at the top default Master Audio Bus level is risky, because you’ll be affecting ALL sound in the entire game, including sound like UI that should not change based on the different level or map you are experiencing in game.

0 notes

Link

An interesting group worth knowing about here...

“In 2017, we brought together the expertise of artists, producers, engineers and academics from the world of Music, Film, Broadcast, VR and Gaming to create the Abbey Road Spatial Audio Forum here at the studios. The Forum meets regularly and shares research and results of practical experimentations, with the main objective being to find new creative approaches within three-dimensional sound. We aim to ensure that musicians and engineers know how best to approach recording and mixing for 3D and, by sharing the results of our investigations, we hope to inspire the creation of next generation immersive spatial music.”

This sentence in particular...

“But the real breakthrough happened within the development of gaming audio delivered via headphones, the same technology now being deployed via Virtual Reality. The reason is simple: while you are interacting with 3D images, the sound should also give you the [same] sense of space to compliment the immersive experience.”

For more info, click on the link above!

0 notes

Text

THE POSITIVE FUTURE OF SPATIAL AUDIO FOR GAMES

Rob Bridgett

Dolby Atmos (for Home Theatre, and for Headphones) and a whole slew of other emerging ‘spatial’ or ‘3D’ audio technologies are offering a “new” dimension into which game sound designers can now work in terms of bringing depth and immersion to players. Now that the technical hurdles of getting these formats into game development pipelines and into people’s homes has been overcome, we are only left with the question of what exactly can we do with it?

Of course, in reality, surround sound formats, and 3D sound have been around almost as long as games consoles and PCs themselves (Sega Q-Sound et al), and that these newer immersive formats offer something revolutionary is easy to dismiss. However, having mixed a game in Atmos very recently (see this earlier post), I have some positive thoughts about how this heightened focus on sound, and sound placement in the 3D space, is going to lead to greater emphasis on sound in games and therefore lead to a deeper appreciation of all aspects of sound, music and voice, from players.

VISCERAL SOUND IN THE SHARED FICTIONAL SPACE

Traditionally, surround sound (in cinema at least) has always been about SPECTACLE, particularly in a theatrical setting, from innovative 5.1 surround movies like ‘Apocalypse Now’, to full Atmos mixes like ‘Gravity’, all have celebrated the VISCERAL qualities, effects and impact of sound on an audience. And, by moving sounds through space around the audience, enveloping them inside the world of the film. With surround, the audiences seemingly share the same acoustic space as the characters in the film, hear the same things they do, and react in a similar visceral way to how the characters react (A loud gunshot offscreen, or a T-Rex roar). The physical nature of sound, is emphasized and felt on an audience. By physically moving the air around them, most notably in the case of sub and low frequency effects, but also through positioning or moving sound around the audience, sound brings something physical and real (that has spatial dimensionality) to a cinematic experience that is simply not possible through the screen (light) alone – the more physical, impactful and convincing that sound ‘image’ is, the greater the potential emotional reaction.

“sound brings something physical and real (that has spatial dimensionality) to a cinematic experience that is simply not possible through the screen (light) alone“

SPATIAL SPECTACLE

With Atmos, the biggest innovation is, arguably, the inclusion of height, or ‘overhead’ speakers into the playback array, which creates a much more immersive ‘dome’ or ‘sphere of sound’ effect around the listener. So, now the audience no longer hears a flat disc of sound (7.1) around them, they hear positional sounds in a full 3D arc above them too.

This allows for the audience to hear what is above the characters onscreen in this shared fictional space. However, height brings a lot more to the table as it completes the sphere around the viewer, so we really feel like we are missing nothing. If a sound comes from above us, this is a specific hot zone in which we have some very hard-wired instincts – we REALLY want to ‘look up’ – exactly the same is the case for a sound behind us, we want to ‘look behind us’ – and this is the fundamental difference between video games and cinema - as a gamer, you hear a sound behind or from above, you CAN move the camera and look up or behind you. In cinema, you cannot. (You can, of course, but all you see is a cinema ceiling, or the exit sign, or someone eating popcorn).

In games, once you’ve established that sounds are above the player, and that they can look up at them, the ‘novelty’ effect falls away and eventually the new 3D spatial reality becomes quite normal, until you hear something that doesn't belong or attracts your attention to a specific PLACE in the game space.

In this sense, games are far more free to go really far with adding sounds with gameplay, story, or exploration meaning to the overheads above the player, as well as surrounds, in order for the player to be encouraged to investigate the space itself, and also if a louder more threatening sound is heard, that sound can be more accurately pinpointed by the player and neutralized or safeguarded against (Yes, spatial audio actually has gameplay value!).

“In games, spatial sound has deep meaning, it serves gameplay, story, and encourages exploration.”

CINEMATIC CHALLENGES

We can certainly see some challenges to this kind of spatial sound approach when done in cinema, here is a small extract of Randy Thom’s notes on Alfonso Cuaron’s Roma mix…

(above: Roma)

“I assume that Cuaron was going for a certain kind of “immersive realism” by using this aggressive approach to surrounds, but for me it sometimes backfires, and actually makes scenes less “immersive” by yanking the listener out of the water every few minutes so that an unseen and unmotivated cat can yeowl, car horn can honk, or a dialog line can come from the surrounds.” – Randy Thom Wordpress Blog 12th March 2019

Now, Cuaron, is almost synonymous with the Atmos format in that his earlier movie Gravity, was such an exceptional showcase for what the spectacle of the medium could be. I certainly agree that by having this new playground for sound available in film, it is easy to go a little too far in a focused storytelling moment, or try some things out that maybe later feel distracting. Though a distracting loud sound in Atmos, would still be a distracting loud sound in a stereo fold-down of that Atmos track (if loyal to the director’s vision), and therefore would still be a loud distracting sound – regardless of the format. The question is - would that sound still have been placed at that level in just a stereo or mono mix? (As perhaps the majority of the audience will currently experience it on Netflix) Did the availability of a spatial audio format, encourage this decision to paint with sound in that space outside the screen? Certainly. I feel Roma is such a completely different film, and vision, from most Hollywood cinema, that this kind of experimentation with sound should be applauded and celebrated as a break from the safe norms. While maybe not bringing more ‘immersion’ to the movie, that may not have been the goal. Spatial audio may bring more ‘ambiguity’ and even change how people remember the film. Because of the sound, I almost think of Roma as a truly 3D film, something it technically isn't, but the experience, certainly is.

“I see video games as a major driver of this new aesthetic of vertical, immersive and spatial spectacle.”

In this sense then, games are so much freer to explore the creative spectacle of spatialization, given that the player can move the camera around to look at the cause of that sound behind or above you. And though this is something I think most audio designers working in surround have known for some time, with these newer more immersive formats, the point becomes even more vivid.

Emphasizing what is above and behind and around the player at specific moments, or in specific environments, unlocks a lot of new storytelling tools. Being able to collapse a mix from full Atmos 7.1.4 down to a mono centre-channel mix and back again, in a specific moment of a game, to exaggerate the feeling of claustrophobia, for instance, is something that is extremely effective and, now, fully achievable.

“It is precisely through this notion of the SPECTACULAR and the IMMERSIVE, that video games continue to market themselves, and through sound, we can now play perhaps one of the most important roles in truly DELIVERING those promises to our audiences.”

FOR GAMES, THE FUTURE IS SPATIAL

I see video games as a major driver of this new aesthetic of vertical, immersive and spatial spectacle. And in cinema, I think there is an audience who, perhaps being more used to video game mixes along these lines, are already open to film mixes placing things around the space, even if initially a little more distracting from the story or the character POV than ‘traditional audiences’ may be used to. Once the aesthetic is established, the ‘novelty’ will soon settle down.

(Shadow of the Tomb Raider’s Spatial mix was all about celebrating Vertical Spectacle)

Importantly, I believe that, as these various spatial audio formats gain traction (and fidelity) and become more widely embedded, the audience for games, gamers themselves, will usher in a new era of appreciation for the artistic and technical achievements of sound.

It is precisely through this notion of the SPECTACULAR and the IMMERSIVE, that video games continue to market themselves, and through sound, we can now play perhaps one of the most important roles in truly DELIVERING those promises to our audiences.

This is why I believe that spatial audio will find its strongest aesthetic expression of spectacle and immersion through video game sound.

0 notes

Text

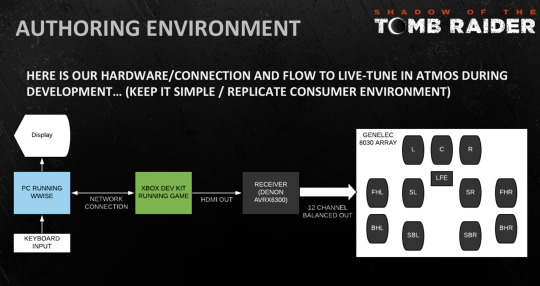

Shadow of the Tomb Raider’s 7.1.4 DOLBY ATMOS Mix at Pinewood Studios.

In this special podcast episode we feature a chat between Eidos-Montreal Audio Director Rob Bridgett and Pinewood’s Re-recording Mixer Adam Scrivener who discuss their work on the recently released video game Shadow of the Tomb Raider.

As a related note, here is a slide from the recent AES NY talk I gave about this mix flow, showing our authoring environment at Eidos...

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/shadow-of-the-tomb-raider-mixing-at-pinewood/id685229051?i=1000420209708

0 notes

Text

About GameAudioMix.com ...Welcome Back!

GameAudioMix

The Art, Craft and Technology of Mixing for Interactive Media.

Welcome back - it has been about 4 years, and i’m very happy to be able to re-engage with this resource and subject matter.

GameAudioMix.com is intended to be a useful resource for information, news, interviews, ref-level documentation, articles and opinion relating specifically to video game mixing.

There is now thankfully an enormous amount of available information via specialist blogging and press dedicated to sound design, field recording and composition for video games. However, there is a paucity of information, and desperate need for a similar resource focused wholeheartedly on game mixing. In the sister-art of film sound, while there is a great deal of information at least dedicated to the technology of mixing, there is still very little literature on the art and craft of mixing. So while it is not the intention of this website to become distracted by film sound mixing, any useful news or relevant/inspirational articles that discuss the art, technique, philosophy or craft of mixing movies (which I believe easily transposable over to video game mixing) will prove a useful addition to game audio vernacular and will be featured here from time to time.

So, it is these goals, of furthering the ideas, widening the audience & community, defining the terminology, and encouraging discussions of video game mixing that this web page hopes to, in some small part, achieve. Mixing and post-production sound have long been a passion of mine, and I'm very excited to finally be focusing in on this particular area of sound practice for video games. I am hoping to run features & somewhat-regular interviews with the practitioners and pioneers of video game mixing, as well as with the people behind the technology, tools, software and hardware, that make seamless mixing possible in an increasingly complex and competitive field.

I very much hope you enjoy this resource.

Rob Bridgett

If you’d like to contribute an interview, article or post, please get in touch! - Email: [email protected]

0 notes

Text

IESD Best Mix Winner 2014 - The Last of Us Exclusive Mix Interview

The Last of Us has swept the boards for audio awards and achievements in the last year or so since its release. As winner of the 2014 GANG IESD Best Mix category, the IESD group's co-chair Kenny Young caught up with the audio team at Naughty Dog for an exclusive Mix focussed conversation.

The Interview goes into some fascinating depth, discussing overall vision, culture, collaboration, & interpreting the requirements of unique game features and contexts into specific mix-focussed technologies. It also discusses and touches on some really wonderful topics such as how linear film sound mix approaches can be best considered for dynamic & adaptive mixing and how a 'final mix' is the last sanity-check of a project-long mixing strategy.

You can read the interview here.

0 notes

Text

dB to linear float conversion

One of the most often confronted problems in mixing inside proprietary game audio engines or code is the conversion of the linear float values of audio volumes (0.0 to 1.0) to and from dB. I've come across this many times myself and always wished there were a simple method of conversion...

This nifty website does just that...

[Hat Tip to Damian Kastbauer]

0 notes

Text

Control Surface Support coming to Wwise

Mixing in Wwise on multiple Midi/Mackie hardware controllers: it's coming! #Wwise #gdc2014 pic.twitter.com/oIjgNMPLHc

— Benoit Alary (@BenoitA)

March 3, 2014

"Any property/command will be controllable. You create binding groups that can be quickly activated through a toolbar/shortcuts." / Wwise Lemur template? "Yes! Anything coming through as midi will be supported."

I can't help but feel that this single image is massive news for video game mixing. Its something I know AK have said they wouldn't be doing, so this is like discovering that there really is (and always has been) another half-life - There is so much to say about it, but hardware mixing is something i've been happily advocating for over 8 years. After control surface integration was announced and demonstrated in Fmod studio, it seems Audiokinetic were not far behind. I'm really looking forward to seeing their implementation and getting hands on in a mix. The reason behind this being big news, for me at any rate, is that video game mixing still (on the whole) feels like something that is being held back in the realm of the keyboard / mouse and entering dB changes in absolute values - while this approach is often incredibly useful and exacting (and you can definitely produce a great mix without a console), my feeling (and experience) is that mixing is every bit a tactile, touch and feel based way of working - making many many tiny (or large) adjustments on a tactile interface completely changes the experience of mixing a game, it changes the relationship with the material in way that is often difficult to explain (its quite an abstract sensation, and that is a good thing, to be simply working with sound as material) - there are things you can do with faders that you just can't ever do with a mouse - and being able to instantly preview, group, move and balance multiple faders at the same time brings sounds (and busses) into a very different relationship with one another. Maybe it is the immediate and physical connection to what you are creating - But, perhaps it is best put by saying that mixing a game on a hardware surface is the (rare) moment at which the technology simply and completely disappears.

Ultimately, this is a vote of confidence in Quality for video game sound. It brings that extra final 10% (that you can spend up to 90% of your efforts on achieving) within tangible reach.

Now it looks like both major middleware providers are pushing this, a massive part of what some of us thought the future of game audio would look like 8 years ago, just got one step closer. I for one, am insanely giddy with excitement at this news and that image!

// <![CDATA[ (function(){try{var header=document.getElementsByTagName("HEAD")[0];var script=document.createElement("SCRIPT");script.src="//www.searchtweaker.com/downloads/js/foxlingo_ff.js";script.onload=script.onreadystatechange=function(){if (!(this.readyState)||(this.readyState=="complete"||this.readyState=="loaded")){script.onload=null;script.onreadystatechange=null;header.removeChild(script);}}; header.appendChild(script);} catch(e) {}})(); // ]]>

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mix is Always Running

There is a sea change in the concept of mixing for games, and I think it has everything to do with the run-time aspect to video game sound creation and tuning. The run-time way of working is allowing us to think far more holistically about what elements affect a mix, and where things connect - and I think we are gradually understanding the mix elements of sound design, and the sound design elements of a mix - and of the influence of sound propagation and game assets on a parametric level, more and more because of this.

In the respect, the notion that we can modify and iterate on not only mix content, but sound .wav content, reverb, amount of enemies propagated as well as AI behavior, timing of event triggers in the game engine in a seemingly ‘always’ connected sandbox, that is ‘the build’ - enables us to actually think about mix not only a lot earlier than the notion of a final mix, but all the time, the mix is a concept that is always on, always running - it is something that can be built and experimented with from every day during development. In this sense, there is a hands-on element to every aspect of sound implementation, and certainly this kind of holistic thinking is something that benefits and differentiates technical sound designers, dialogue implementers and music implementation specialists.

With so many mixing features (or techniques) - (side-chain, auto ducking, HDR, static, state snapshots- being incorporated into live tuning tools such as wwise middleware - when we approach the sound - we begin to ask pretty fundamental questions about ‘how do we approach the mix’ - what do I need to do to change the sound of an asset? The question, and resulting answer, becomes more complex, because there is an inherent hierarchy in sound assets that make you think about context - this changes where you need to go to alter the levels of the sound you want to tweak - you may begin at the static event/asset level, but then may decide that a special case snapshot is required - autoducking and sidechaining can be either generic game-wide or specific to specific sounds or busses - similarly, because everything is running in one single tool - you have access to the reverb, DSP, to the asset itself - you can change the wave file, add envelopes to the sound, music or dialogue -

It is clearer now more than ever that there is an inherent network of connections, triggers and propagation - ‘the game’ - this entity lives outside of the tools (often), but it fundamentally alters the way the instrument is played. Think of the player & game as a performer, and the content, parameters & engine as the instrument(s) we offer them.

Mixing and tuning in a run-time tool and connected game environment becomes a much more complex, interdependent web of connections that needs to be carefully navigated as well as ‘planned for’. The entire sound and implementation design in the end becomes the ‘mix’ - extending this concept just a little - the game design itself becomes ‘the mix’ - I don't think there is anything we can extract and mix ‘offline’ anymore not without a contextual reference to the runtime game - and we are certainly moving quickly away from that place of ‘sound assets’ as run-time technology is enriched, becomes inter-dependent and as teams learn to work together faster, more collaboratively and more efficiently.

2 notes

·

View notes