I like many things, maybe I'll post some drawings, maybe not...

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Vander: I've always liked the name Violet. Silco: *snorts a line* Hey, you know what I like?

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

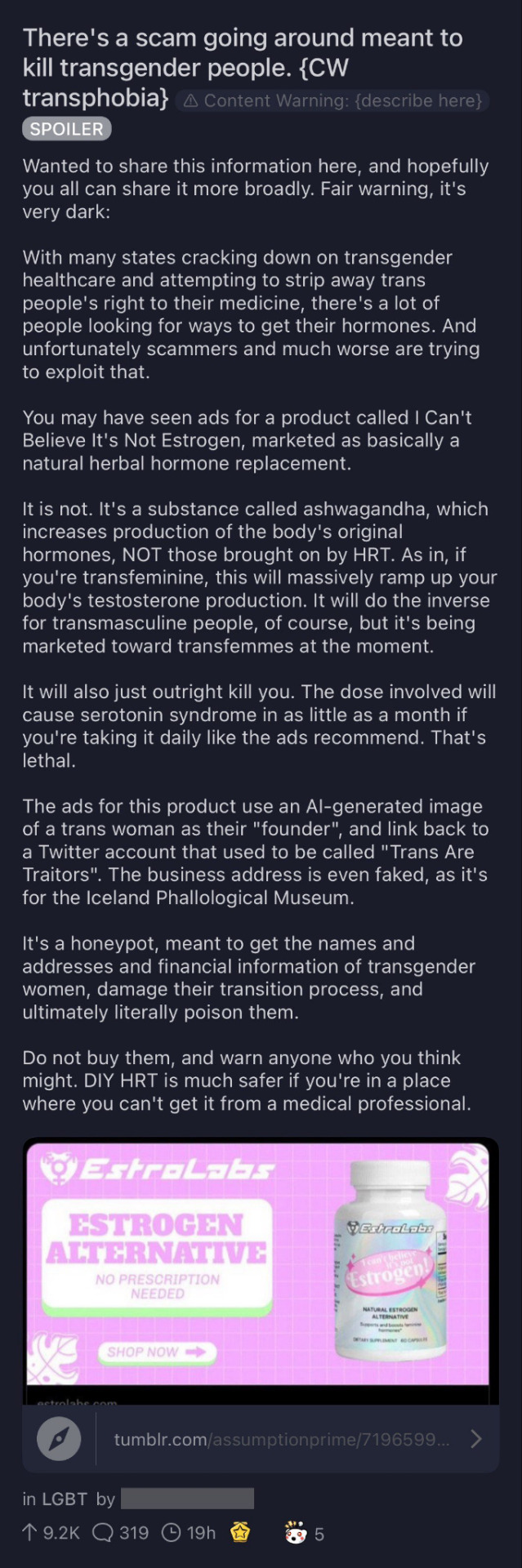

Don't Fall for this scam.

Transgender community, please please please do NOT use this product! It will kill you if used, please do not use it whatsoever.

Please reblog and spread the word

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

hi chat, guess who transcribed Alex Hirsch’s pitch for the book of bill that he showed off for nycc

668 notes

·

View notes

Text

what would YOU know about shirley pepperton anyway!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Can you believe it that this old fanart (2nd pic) is turning 10 years old? I can’t believe it.. time goes by really fast :(

970 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel that one of the most overlooked aspects of studying the French Revolution is that, in 18th-century France, most people did not speak French. Yes, you read that correctly.

On 26 Prairial, Year II (14 June 1794), Abbé Henri Grégoire (1) stood before the Convention and delivered a report called The Report on the Necessity and Means of Annihilating Dialects and Universalising the Use of the French Language(2). This report, the culmination of a survey initiated four years earlier, sought to assess the state of languages in France. In 1790, Grégoire sent a 43-question survey to 49 informants across the departments, asking questions like: "Is the use of the French language universal in your area?" "Are one or more dialects spoken here?" and "What would be the religious and political impact of completely eradicating this dialect?"

The results were staggering. According to Grégoire's report:

“One can state without exaggeration that at least six million French people, especially in rural areas, do not know the national language; an equal number are more or less incapable of holding a sustained conversation; and, in the final analysis, those who speak it purely do not exceed three million; likely, even fewer write it correctly.” (3)

Considering that France’s population at the time was around 27 million, Grégoire’s assertion that 12 million people could barely hold a conversation in French is astonishing. This effectively meant that about 40% of the population couldn't communicate with the remaining 60%.

Now, it’s worth noting that Grégoire’s survey was heavily biased. His 49 informants (4) were educated men—clergy, lawyers, and doctors—likely sympathetic to his political views. Plus, the survey barely covered regions where dialects were close to standard French (the langue d’oïl areas) and focused heavily on the south and peripheral areas like Brittany, Flanders, and Alsace, where linguistic diversity was high.

Still, even if the numbers were inflated, the takeaway stands: a massive portion of France did not speak Standard French. “But surely,” you might ask, “they could understand each other somewhat, right? How different could those dialects really be?” Well, let’s put it this way: if Barère and Robespierre went to lunch and spoke in their regional dialects—Gascon and Picard, respectively—it wouldn’t be much of a conversation.

The linguistic make-up of France in 1790

The notion that barely anyone spoke French wasn’t new in the 1790s. The Ancien Régime had wrestled with it for centuries. The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, issued in 1539, mandated the use of French in legal proceedings, banning Latin and various dialects. In the 17th and 18th centuries, numerous royal edicts enforced French in newly conquered provinces. The founding of the Académie Française in 1634 furthered this control, as the Académie aimed to standardise French, cementing its status as the kingdom's official language.

Despite these efforts, Grégoire tells us that 40% of the population could barely speak a word of French. So, if they didn’t speak French, what did they speak? Let’s take a look.

In 1790, the old provinces of the Ancien Régime were disbanded, and 83 departments named after mountains and rivers took their place. These 83 departments provide a good illustration of the incredibly diverse linguistic make-up of France.

Langue d’oïl dialects dominated the north and centre, spoken in 44 out of the 83 departments (53%). These included Picard, Norman, Champenois, Burgundian, and others—dialects sharing roots in Old French. In the south, however, the Occitan language group took over, with dialects like Languedocien, Provençal, Gascon, Limousin, and Auvergnat, making up 28 departments (34%).

Beyond these main groups, three departments in Brittany spoke Breton, a Celtic language (4%), while Alsatian and German dialects were prevalent along the eastern border (another 4%). Basque was spoken in Basses-Pyrénées, Catalan in Pyrénées-Orientales, and Corsican in the Corse department.

From a government’s perspective, this was a bit of a nightmare.

Why is linguistic diversity a governmental nightmare?

In one word: communication—or the lack of it. Try running a country when half of it doesn’t know what you’re saying.

Now, in more academic terms...

Standardising a language usually serves two main purposes: functional efficiency and national identity. Functional efficiency is self-evident. Just as with the adoption of the metric system, suppressing linguistic variation was supposed to make communication easier, reducing costly misunderstandings.

That being said, the Revolution, at first, tried to embrace linguistic diversity. After all, Standard French was, frankly, “the King’s French” and thus intrinsically elitist—available only to those who had the money to learn it. In January 1790, the deputy François-Joseph Bouchette proposed that the National Assembly publish decrees in every language spoken across France. His reasoning? “Thus, everyone will be free to read and write in the language they prefer.”

A lovely idea, but it didn’t last long. While they made some headway in translating important decrees, they soon realised that translating everything into every dialect was expensive. On top of that, finding translators for obscure dialects was its own nightmare. And so, the Republic’s brief flirtation with multilingualism was shut down rather unceremoniously.

Now, on to the more fascinating reason for linguistic standardisation: national identity.

Language and Nation

One of the major shifts during the French Revolution was in the concept of nationhood. Today, there are many ideas about what a nation is (personally, I lean towards Benedict Anderson’s definition of a nation as an “imagined community”), but definitions aside, what’s clear is that the Revolution brought a seismic change in the notion of French identity. Under the Ancien Régime, the French nation was defined as a collective that owed allegiance to the king: “One faith, one law, one king.” But after 1789, a nation became something you were meant to want to belong to. That was problematic.

Now, imagine being a peasant in the newly-created department of Vendée. (Hello, Jacques!) Between tending crops and trying to avoid trouble, Jacques hasn’t spent much time pondering his national identity. Vendéen? Well, that’s just a random name some guy in Paris gave his region. French? Unlikely—he has as much in common with Gascons as he does with the English. A subject of the King? He probably couldn’t name which king.

So, what’s left? Jacques is probably thinking about what is around him: family ties and language. It's no coincidence that the ‘brigands’ in the Vendée organised around their parishes— that’s where their identity lay.

The Revolutionary Government knew this. The monarchy had understood it too and managed to use Catholicism to legitimise their rule. The Republic didn't have such a luxury. As such, the revolutionary government found itself with the impossible task of convincing Jacques he was, in fact, French.

How to do that? Step one: ensure Jacques can actually understand them. How to accomplish that? Naturally, by teaching him.

Language Education during the Revolution

Under the Ancien Régime, education varied wildly by class, and literacy rates were abysmal. Most commoners received basic literacy from parish and Jesuit schools, while the wealthy enjoyed private tutors. In 1791, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand (5) presented a report on education to the Constituent Assembly (6), remarking:

“A striking peculiarity of the state from which we have freed ourselves is undoubtedly that the national language, which daily extends its conquests beyond France’s borders, remains inaccessible to so many of its inhabitants." (7)

He then proposed a solution:

“Primary schools will end this inequality: the language of the Constitution and laws will be taught to all; this multitude of corrupt dialects, the last vestige of feudalism, will be compelled to disappear: circumstances demand it." (8)

A sensible plan in theory, and it garnered support from various Assembly members, Condorcet chief among them (which is always a good sign).

But, France went to war with most of Europe in 1792, making linguistic diversity both inconvenient and dangerous. Paranoia grew daily, and ensuring the government’s communications were understood by every citizen became essential. The reverse, ensuring they could understand every citizen, was equally pressing. Since education required time and money—two things the First Republic didn’t have—repression quickly became Plan B.

The War on Patois

This repression of regional languages was driven by more than abstract notions of nation-building; it was a matter of survival. After all, if Jacques the peasant didn’t see himself as French and wasn’t loyal to those shadowy figures in Paris, who would he turn to? The local lord, who spoke his dialect and whose land his family had worked for generations.

Faced with internal and external threats, the revolutionary government viewed linguistic unity as essential to the Republic’s survival. From 1793 onwards, language policy became increasingly repressive, targeting regional dialects as symbols of counter-revolution and federalist resistance. Bertrand Barère spearheaded this campaign, famously saying:

“Federalism and superstition speak Breton; emigration and hatred of the Republic speak German; counter-revolution speaks Italian, and fanaticism speaks Basque. Let us break these instruments of harm and error... Among a free people, the language must be one and the same for all.”

This, combined with Grégoire’s report, led to the Décret du 8 Pluviôse 1794, which mandated French-speaking teachers in every rural commune of departments where Breton, Italian, Basque, and German were the main languages.

Did it work? Hardly. The idea of linguistic standardisation through education was sound in principle, but France was broke, and schools cost money. Spoiler alert: France wouldn’t have a free, secular, and compulsory education system until the 1880s.

What it did accomplish, however, was two centuries of stigmatising patois and their speakers...

Notes

(1) Abbe Henri Grégoire was a French Catholic priest, revolutionary, and politician who championed linguistic and social reforms, notably advocating for the eradication of regional dialects to establish French as the national language during the French Revolution.

(2) "Sur la nécessité et les moyens d’anéantir les patois et d’universaliser l’usage de la langue francaise”

(3)On peut assurer sans exagération qu’au moins six millions de Français, sur-tout dans les campagnes, ignorent la langue nationale ; qu’un nombre égal est à-peu-près incapable de soutenir une conversation suivie ; qu’en dernier résultat, le nombre de ceux qui la parlent purement n’excède pas trois millions ; & probablement le nombre de ceux qui l’écrivent correctement est encore moindre.

(4) And, as someone who has done A LOT of statistics in my lifetime, 49 is not an appropriate sample size for a population of 27 million. At a confidence level of 95% and with a margin of error of 5%, he would need a sample size of 384 people. If he wanted to lower the margin of error at 3%, he would need 1,067. In this case, his margin of error is 14%.

That being said, this is a moot point anyway because the sampled population was not reflective of France, so the confidence level of the sample is much lower than 95%, which means the margin of error is much lower because we implicitly accept that his sample does not reflect the actual population.

(5) Yes. That Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand. It’s always him. He’s everywhere. If he hadn’t died in 1838, he’d probably still be part of Macron’s cabinet. Honestly, he’s probably haunting the Élysée as we speak — clearly the man cannot stay away from politics.

(6) For those new to the French Revolution and the First Republic, we usually refer to two legislative bodies, each with unique roles. The National Assembly (1789): formed by the Third Estate to tackle immediate social and economic issues. It later became the Constituent Assembly, drafting the 1791 Constitution and establishing a constitutional monarchy.

(7) Une singularité frappante de l'état dont nous sommes affranchis est sans doute que la langue nationale, qui chaque jour étendait ses conquêtes au-delà des limites de la France, soit restée au milieu de nous inaccessible à un si grand nombre de ses habitants.

(8) Les écoles primaires mettront fin à cette étrange inégalité : la langue de la Constitution et des lois y sera enseignée à tous ; et cette foule de dialectes corrompus, dernier reste de la féodalité, sera contraint de disparaître : la force des choses le commande

(9) Le fédéralisme et la superstition parlent bas-breton; l’émigration et la haine de la République parlent allemand; la contre révolution parle italien et le fanatisme parle basque. Brisons ces instruments de dommage et d’erreur. .. . La monarchie avait des raisons de ressembler a la tour de Babel; dans la démocratie, laisser les citoyens ignorants de la langue nationale, incapables de contréler le pouvoir, cest trahir la patrie, c'est méconnaitre les bienfaits de l'imprimerie, chaque imprimeur étant un instituteur de langue et de législation. . . . Chez un peuple libre la langue doit étre une et la méme pour tous.

(10) Patois means regional dialect in French.

595 notes

·

View notes

Text

Master and Margarita dashboard simulator

👤 deactivated-302bis

censor this dick

🎈bezdomnyyyy Follow

op why did you deactivate

🎈bezdomnyyyy Follow

nvm i figured it out

🎈bezdomnyyyy Follow

be honest guys if im good enough for wattpad can i make it to ao3 🥹

🎭 messire Follow

you will not survive the winter

🎈bezdomnyyyy Follow

a no would've been enough

🐀 marcus-muribellum Follow

yeshua ha-nozri kinda mid

📜 matthewlevi-n1christian Follow

jerusalem, palestine, 31.779400, 35.232071

💬 anonymous:

i must say im so disappointed in you. i heard you tried to get acquainted with the procurator during your trial and even offered your miracles to him. you promised to sacrifice yourself and wash our sins away!

🌾 yeshuafromtheblock Follow

doesn't sound like me

🌾 yeshuafromtheblock Follow

@matthewlevi-n1christian WHEN I CATCH YOU

🧐 misha-bulgakov Follow

God at the pearly gates: look its really simple the only rule for getting in is you dont have to have written faust self insert fanfiction where your wife befriends magic stalin and beats the shit out of people you dont like

Me: ok hear me out

👤 not-the-kgb Follow

hey man what the fuck

🌻 miss-margo Follow

god please bring back my husband

🌻 miss-margo Follow

not my actual husband ew

🌻 miss-margo Follow

its been six months and nothing happened. time to switch teams

#hot witch easter

🐈⬛️ hippocat Follow

i miss when gingers got hunted down for fun

👩🦰 vampwitch Follow

no borsch for you

🐈⬛️ hippocat Follow

just the men though

🎈bezdomnyyyy Follow

who even uses ъ anymore

🎭 messire Follow

have you thought that maybe people who were there when the glagolitic script was created still need it...

👩🦰 vampwitch Follow

so insensitive of you op

🔫 azazello-with-an-o Follow

literally why dont they kick you out of the party

🃏 retired-jester-club Follow

im on the phone with poprichin rn they're revoking your massolit card

🐈⬛️ hippocat Follow

homeless AND jobless, pick a struggle

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Women of the French Revolution (and even the Napoleonic Era) and Their Absence of Activism or Involvement in Films

Warning: I am currently dealing with a significant personal issue that I’ve already discussed in this post: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/765252498913165313/the-scars-of-a-toxic-past-are-starting-to-surface?source=share. I need to refocus on myself, get some rest, and think about what I need to do. I won’t be around on Tumblr or social media for a few days (at most, it could last a week or two, though I don’t really think it will).

But don’t worry about me—I’m not leaving Tumblr anytime soon. I just wanted to let you know so you don’t worry if you don’t see me and have seen this post.

I just wanted to finish this post, which I’d already started three-quarters of the way through.

One aspect that frustrates me in film portrayals (a significant majority, around 95%) is the way women of the Revolution or even the Napoleonic era are depicted. Generally, they are shown as either "too gentle" (if you know what I mean), merely supporting their husbands or partners in a purely romantic way. Just look at Lucile Desmoulins—she is depicted as a devoted lover in most films but passive and with little to say about politics.

Yet there’s so much to discuss regarding women during this revolutionary period. Why don’t we see mention of women's clubs in films? There were over 50 in France between 1789 and 1793. Why not mention Etta Palm d’Alders, one of the founders of the Société Patriotique et de Bienfaisance des Amies de la Vérité, who fought for the right to divorce and for girls' education? Or the cahier from the women of Les Halles, requesting that wine not be taxed in Paris?

Only once have I seen Louise Reine Audu mentioned in a film (the excellent Un peuple et son Roi), a Parisian market woman who played a leading role in the Revolution. She led the "dames des halles" and on October 5, 1789, led a procession from Paris to Versailles in this famous historical event. She was imprisoned in September 1790, amnestied a year later through the intervention of Paris mayor Pétion, and later participated in the storming of the Tuileries on August 10, 1792. Théroigne de Méricourt appears occasionally as a feminist, but her mission is often distorted. She was not a Girondin, as some claim, but a proponent of reconciliation between the Montagnards and the Girondins, believing women had a key role in this process (though she did align with Brissot on the war question). She was a hands-on revolutionary, supporting the founding of societies with Charles Gilbert-Romme and demanding the right to bear arms in her Amazon attire.

Why is there no mention in films of Pauline Léon and Claire Lacombe, two well-known women of the era? Pauline Léon was more than just a fervent supporter of Théophile Leclerc, a prominent ultra-revolutionary of the "Enragés." She was the eldest daughter of chocolatier parents, her father a philosopher whom she described as very brilliant. She was highly active in popular societies. Her mother and a neighbor joined her in protesting the king’s flight and at the Champ-de-Mars protest in July 1791, where she reportedly defended a friend against a National Guard soldier. Along with other women (and 300 signatures, including her mother’s), she petitioned for women’s rights. She participated in the August 10 uprising, attacked Dumouriez in a session of the Société fraternelle des patriotes des deux sexes, demanded the King’s execution, and called for nobles to be banned from the army at the Jacobin Club, in the name of revolutionary women. She joined her husband Leclerc in Aisne where he was stationed (see @anotherhumaninthisworld’s excellent post on Pauline Léon). Claire Lacombe was just as prominent at the time and shared her political views. She was one of those women, like Théroigne de Méricourt, who advocated taking up arms to fight the tyrant. She participated in the storming of the Tuileries in 1792 and received a civic crown, like Louise Reine Audu and Théroigne de Méricourt. She was active at the Jacobin Club before becoming secretary, then president of the Société des Citoyennes Républicaines Révolutionnaires (Society of Revolutionary Republican Women). Contrary to popular belief, there’s no evidence she co-founded this society (confirmed by historian Godineau). Lacombe demanded the trial of Marie Antoinette, stricter measures against suspects, prosecution of Girondins by the Revolutionary Tribunal, and the application of the Constitution. She also advocated for greater social rights, as expressed in the Enragés petition, which would later be adopted by the Exagérés, who were less suspicious of delegated power and saw a role beyond the revolutionary sections.

Olympe de Gouges did not call for women to bear arms; in her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, addressed to the Queen after the royal family’s attempted escape, she demanded gender equality. She famously said, "A woman has the right to mount the scaffold; she must equally have the right to mount the rostrum," and denounced the monarchy when Louis XVI's betrayal became undeniable, although she sought clemency for him and remained a royalist. She could be both a patriot and a moderate (in the conservative sense; moderation then didn’t necessarily imply clemency but rather conservative views on certain matters).

Why Are Figures Like Manon Roland Hardly Mentioned in These Films?

In most films, Manon Roland is barely mentioned, or perhaps given a brief appearance, despite being a staunch republican from the start who worked toward the fall of the King and was more than just a supporter of her husband, Roland. She hosted a salon where political ideas were exchanged and was among those who contributed to the monarchy's downfall. Of course, she was one of those courageous women who, while brave, did not advocate for women’s rights. It’s essential to note that just because some women fought in the Revolution or displayed remarkable courage doesn’t mean they necessarily advocated for greater rights for women (even Olympe de Gouges, as I mentioned earlier, had her limits on gender equality, as she did not demand the right for women to bear arms).

Speaking of feminism, films could also spotlight Sophie de Grouchy, the wife and influence behind Condorcet, one of the few deputies (along with Charles Gilbert-Romme, Guyomar, Charlier, and others) who openly supported political and civic rights for women. Without her, many of Condorcet’s posthumous works wouldn’t have seen the light of day; she even encouraged him to draft Sketch and received several pages to publish, which she did. Like many women, she hosted a salon for political discussion, making her a true political thinker.

Then there’s Rosalie Jullien, a highly cultured woman and wife of Marc-Antoine Jullien, whose sons were fervent revolutionaries. She played an essential role during the Revolution, actively involving herself in public affairs, attending National Assembly sessions, staying informed of political debates and intrigues, and even sending her maid Marion to gather information on the streets. Rosalie’s courage is evident in her steadfastness, as she claimed she would "stay at her post" despite the upheaval, loyal to her patriotic and revolutionary ideals. Her letters offer invaluable insights into the Revolution. She often discussed public affairs with prominent revolutionaries like the Robespierre siblings and influential figures like Barère.

Lucile Desmoulins is another figure. She was not just the devoted lover often depicted in films; she was a fervent supporter of the French Revolution. From a young age, her journal reveals her anti-monarchist sentiments (no wonder she and Camille Desmoulins, who shared her ideals, were such a united couple). She favored the King’s execution without delay and wholeheartedly supported Camille in his publication, Le Vieux Cordelier. When Guillaume Brune urged Camille to tone down his criticism of the Year II government, Lucile famously responded, “Let him be, Brune. He must save his country; let him fulfill his mission.” She also corresponded with Fréron on the political situation, proving herself an indispensable ally to Camille. Lucile left a journal, providing historical evidence that counters the infantilization of revolutionary women. Sadly, we lack personal journals from figures like Éléonore Duplay, Sophie Momoro, or Claire Lacombe, which has allowed detractors to argue (incorrectly) that these women were entirely under others' influence.

Additionally, there were women who supported Marat, like his sister Albertine Marat and his "wife"Simone Evrard, without whom he might not have been as effective. They were politically active throughout their lives, regularly attending political clubs and sharing their political views. Simone Evrard, who inspired much admiration, was deeply committed to Marat’s work. Marat had promised her marriage, and she was warmly received by his family. She cared for Marat, hiding him in the cellar to protect him from La Fayette’s soldiers. At age 28, Simone played a vital role in Marat’s life, both as a partner and a moral supporter. At this time, Marat, who was 20 years her senior, faced increasing political isolation; his radical views and staunch opposition to the newly established constitutional monarchy had distanced him from many revolutionaries.

Despite the circumstances, Simone actively supported Marat, managing his publications. With an inheritance from her late half-sister Philiberte, Simone financed Marat’s newspaper in 1792, setting up a press in the Cordeliers cloister to ensure the continued publication of Marat’s revolutionary pamphlets. Although Marat also sought public funds, such as from minister Jean-Marie Roland, it was mainly Simone’s resources that sustained L’Ami du Peuple. Simone and Marat also planned to publish political works, including Chains of Slavery and a collection of Marat’s writings. After Marat’s assassination in July 1793, Simone continued these projects, becoming the guardian of his political legacy. Thanks to her support, Marat maintained his influence, continuing his revolutionary struggle and exposing the “political machination” he opposed.

Simone’s home on Rue des Cordeliers also served as an annex for Marat’s printing press. This setup combined their personal life with professional activities, incorporating security measures to protect Marat. Simone, her sister Catherine, and their doorkeeper, Marie-Barbe Aubain, collaborated in these efforts, overseeing the workspace and its protection.

On July 13, 1793, Jean-Paul Marat was assassinated by Charlotte Corday. Simone Evrard was present and immediately attempted to help Marat and make sure that Charlotte Corday was arrested . She provided precise details about the circumstances of the assassination, contributing significantly to the judicial file that would lead to Corday’s condemnation.

After Marat’s death, Simone was widely recognized as his companion by various revolutionaries and orators who praised her dignity, and she was introduced to the National Convention by Robespierre on August 8, 1793 when she make a speech against Theophile Leclerc,Jacques Roux, Carra, Ducos,Dulaure, Pétion... Together with Albertine Marat (who also left written speeches from this period), Simone took on the work of preserving and publishing Marat’s political writings. Her commitment to this cause led to new arrests after Robespierre's fall, exposing the continued hostility of factions opposed to Marat’s supporters, even after his death.

Moreover, Jean-Paul Marat benefited from the support of several women of the Revolution, and he would not have been as effective without them.

The Duplay sisters were much more politically active than films usually portray. Most films misleadingly present them as mere groupies (considering that their father is often incorrectly shown as a simple “yes-man” in these same, often misogynistic, films, it's no surprise the treatment of women is worse).

Élisabeth Le Bas, accompanied her husband Philippe Le Bas on a mission to Alsace, attended political sessions, and bravely resisted prison guards who urged her to marry Thermidorians, expressing her anger with great resolve. She kept her husband’s name, preserving the revolutionary legacy through her testimonies and memoirs. Similarly, Éléonore Duplay, Robespierre’s possible fiancée, voluntarily confined herself to care for her sister, suffered an arrest warrant, and endured multiple prison transfers. Despite this, they remained politically active, staying close to figures in the Babouvist movement, including Buonarroti, with whom Éléonore appeared especially close, based on references in his letters.

Henriette Le Bas, Philippe Le Bas's sister, also deserves more recognition. She remained loyal to Élisabeth and her family through difficult times, even accompanying Philippe, Saint-Just, and Élisabeth on a mission to Alsace. She was briefly engaged to Saint-Just before the engagement was quickly broken off, later marrying Claude Cattan. Together with Éléonore, she preserved Élisabeth’s belongings after her arrest. Despite her family’s misfortunes—including the detention of her father—Henriette herself was surprisingly not arrested. Could this be another coincidence when it came to the wives and sisters of revolutionaries, or perhaps I missed part of her story?

Charlotte Robespierre, too, merits more focus. She held her own political convictions, sometimes clashing with those of her brothers (perhaps often, considering her political circle was at odds with their stances). She lived independently, never marrying, and even accompanied her brother Augustin on a mission for the Convention. Tragically, she was never able to reconcile with her brothers during their lifetimes. For a long time, I believed that Charlotte’s actions—renouncing her brothers to the Thermidorians after her arrest, trying to leverage contacts to escape her predicament, accepting a pension from Bonaparte, and later a stipend under Louis XVIII—were all a matter of survival, given how difficult life was for a single woman then. I saw no shame in that (and I still don’t). The only aspect I faulted her for was embellishing reality in her memoirs, which contain some disputable claims. But I recently came across a post by @saintejustitude on Charlotte Robespierre, and honestly, it’s one of the best (and most well-informed) portrayals of her.

As for the the hébertists womens , films could cover Sophie Momoro more thoroughly, as she played the role of the Goddess of Reason in her husband’s de-Christianization campaigns, managed his workshop and printing presses in his absence accompanying Momoro on a mission on Vendée. Momoro expressed his wife's political opinion on the situation in a letter. She also drafted an appeal for assistance to the Convention in her husband’s characteristic style.

Marie Françoise Goupil, Hébert’s wife, is likewise only shown as a victim (which, of course, she was—a victim of a sham trial and an unjust execution, like Lucile Desmoulins). However, there was more to her story. Here’s an excerpt from a letter she wrote to her husband’s sister in the summer of 1792 that reveals her strong political convictions:

« You are very worried about the dangers of the fatherland. They are imminent, we cannot hide them: we are betrayed by the court, by the leaders of the armies, by a large part of the members of the assembly; many people despair; but I am far from doing so, the people are the only ones who made the revolution. It alone will support her because it alone is worthy of it. There are still incorruptible members in the assembly, who will not fear to tell it that its salvation is in their hands, then the people, so great, will still be so in their just revenge, the longer they delay in striking the more it learns to know its enemies and their number, the more, according to me, its blows will only strike with certainty and only fall on the guilty, do not be worried about the fate of my worthy husband. He and I would be sorry if the people were enslaved to survive the liberty of their fatherland, I would be inconsolable if the child I am carrying only saw the light of day with the eyes of a slave, then I would prefer to see it perish with me ».

There is also Marie Angélique Lequesne, who played a notable role while married to Ronsin (and would go on to have an important role during the Napoleonic era, which we’ll revisit later). Here’s an excerpt from Memoirs, 1760-1820 by Jean-Balthazar de Bonardi du Ménil (to be approached with caution): “Marie-Angélique Lequesne was caught up in the measures taken against the Hébertists and imprisoned on the 1st of Germinal at the Maison d'Arrêt des Anglaises, frequently engaging with ultra-revolutionary circles both before and after Ronsin’s death, even dressing as an Amazon to congratulate the Directory on a victory.” According to Généanet (to be taken with even more caution), she may have served as a canteen worker during the campaign of 1792.

On the Babouvist side, we can mention Marie Anne Babeuf, one of Gracchus Babeuf’s closest collaborators. Marie Anne was among her husband's staunchest political supporters. She printed his newspaper for a long time, and her activism led to her two-day arrest in February 1795. When her husband was arrested while she was pregnant, she made every effort possible to secure his release and never gave up on him. She walked from Paris to Vendôme to attend his trial, witnessing the proceeding that would sentence him to death. A few months after Gracchus Babeuf’s execution, she gave birth to their last son, Caius. Félix Lepeletier became a protector of the family (and apparently, Turreau also helped, supposedly adopting Camille Babeuf—one of his very few positive acts). Marie Anne supported her children through various small jobs, including as a market vendor, while never giving up her activism and remaining as combative as ever. (There’s more to her story during the Napoleonic era as well).

We must not forget the role of active women in the insurrections of Year III, against the Assembly, which had taken a more conservative turn by then. Here’s historian Mathilde Larrère’s description of their actions: “In April and May 1795, it was these women who took to the streets, beating drums across the city, mocking law enforcement, entering shops, cafes, and homes to call for revolt. In retaliation, the Assembly decreed that women were no longer allowed to attend Assembly sessions and expelled the knitters by force. Days later, a decree banned them from attending any assemblies and from gathering in groups of more than five in the streets.”

There were also women who fought as soldiers during the French Revolution, such as Marie-Thérèse Figueur, known as “Madame Sans-Gêne.” The Fernig sisters, aged 22 and 17, threw themselves into battle against Austrian soldiers, earning a reputation for their combat prowess and later becoming aides-de-camp to Dumouriez. Other fighting women included the gunners Pélagie Dulière and Catherine Pochetat.

In the overseas departments, there was Flore Bois Gaillard, a former slave who became a leader of the “Brigands” revolt on the island of Saint Lucia during the French Revolution. This group, composed of former slaves, French revolutionaries, soldiers, and English deserters, was determined to fight against English regiments using guerrilla tactics. The group won a notable victory, the Battle of Rabot in 1795, with the assistance of Governor Victor Hugues and, according to some accounts, with support from Louis Delgrès and Pelage.

On the island of Saint-Domingue, which would later become Haiti, Cécile Fatiman became one of the notable figures at the start of the Haitian Revolution, especially during the Bois-Caiman revolt on August 14, 1791.

In short, the list of influential women is long. We could also talk about figures like Félicité Brissot, Sylvie Audouin (from the Hébertist side), Marguerite David (from the Enragés side), and more. Figures like Theresia Cabarrus, who wielded influence during the Directory (especially when Tallien was still in power), or the activities of Germaine de Staël (since it’s essential to mention all influential women of the Revolution, regardless of political alignment) are also noteworthy.

Napoleonic Era

Films could have focused more on women during this era. Instead, we always see the Bonaparte sisters (with Caroline cast as an exaggerated villain, almost like a cartoon character), or Hortense Beauharnais, who’s shown solely as a victim of Louis Bonaparte and portrayed as naïve. There is so much more to say about this time, even if it was more oppressive for women.

Germaine de Staël is barely mentioned, which is unfortunate, and Marie Anne Babeuf is even more overlooked, despite her being questioned by the Napoleonic police in 1801 and raided in 1808. She also suffered the loss of two more children: Camille Babeuf, who died by suicide in 1814, and Caius, reportedly killed by a stray bullet during the 1814 invasion of Vendôme. No mention is made of Simone Evrard and Albertine Marat, who were arrested and interrogated in 1801.

An important but lesser-known event in popular culture was the deportation and imprisonment of the Jacobins, as highlighted by Lenôtre. Here’s an excerpt: “This petition reached Paris in autumn 1804 and was filed away in the ministry's records. It didn’t reach the public, who had other amusements besides the old stories of the Nivôse deportees. It was, after all, the time when the Republic, now an Empire, was preparing to receive the Pope from Rome to crown the triumphant Caesar. Yet there were people in Paris who thought constantly about the Mahé exiles—their wives, most left without support, living in extreme poverty; mothers were the hardest hit. Even if one doesn’t sympathize with the exiles themselves, one can feel pity for these unfortunate women... They implored people in their neighborhoods and local suppliers to testify on behalf of their husbands, who were wise, upstanding, good fathers, and good spouses. In most cases, these requests came too late... After an agonizing wait, the only response they received was, ‘Nothing to be done; he is gone.’” (Les Derniers Terroristes by Gérard Lenôtre). Many women were mobilized to help the Jacobins. One police report references a woman named Madame Dufour, “wife of the deportee Dufour, residing on Rue Papillon, known for her bold statements; she’s a veritable fury, constantly visiting friends and associates, loudly proclaiming the Jacobins’ imminent success. This woman once played a role in the Babeuf conspiracy; most of their meetings were held at her home…” (Unfortunately for her, her husband had already passed away.)

On the Napoleonic “allies” side, Marie Angélique, the widow of Ronsin who later married Turreau, should be more highlighted. Turreau treated her so poorly that it even outraged Washington’s political class. She was described as intelligent, modest, generous, and curious, and according to future First Lady Dolley Madison, she charmed Washington’s political circles. She played an essential role in Dolley Madison’s political formation, contributing to her reputation as an active, politically involved First Lady. Marie Angélique eventually divorced Turreau, though he refused to fund her return to France; American friends apparently helped her.

Films could also portray Marie-Jacqueline Sophie Dupont, wife of Lazare Carnot, a devoted and loving partner who even composed music for his poems. Additionally, her ties with Joséphine de Beauharnais could be explored. They were close friends, which is evident in a heartbreaking letter Lazare Carnot wrote to Joséphine on February 6, 1813, to inform her of Sophie’s death: “Until her last moment, she held onto the gratitude Your Majesty had honored her with; in her memory, I must remind Your Majesty of the care and kindness that characterize you and are so dear to every sensitive soul.”

In films, however, when Joséphine de Beauharnais’s circle is shown, Theresia Cabarrus (who appears much more in Joséphine ou la comédie des ambitions) and the Countess of Rémusat are mentioned, but Sophie Carnot is omitted, which is a pity. Sophie Carnot knew how to uphold social etiquette well, making her an ideal figure to be integrated into such stories (after all, she was the daughter of a former royal secretary).

Among women soldiers, we had Marie-Thérèse Figueur as well as figures like Maria Schellink, who also deserves greater representation. Speaking of fighters, films could further explore the stories of women who took up arms against the illegal reinstatement of slavery. In Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, many women gave their lives, including Sanité Bélair, lieutenant of Toussaint Louverture, considered the soul of the conspiracy along with her husband, Charles Bélair (Toussaint’s nephew) and a fighter against Leclerc. Captured, sentenced to death, and executed with her husband, she showed great courage at her execution. Thomas Madiou's Histoire d’Haiti describes the final moments of the Bélair couple: “When Charles Bélair was placed in front of the squad to be shot, he calmly listened to his wife exhorting him to die bravely... (...)Sanité refused to have her eyes covered and resisted the executioner’s efforts to make her bend down. The officer in charge of the squad had to order her to be shot standing.”

Dessalines, known for leading Haiti to victory against Bonaparte, had at least three influential women in his life. One was his mentor in combat and a mother figure, the former slave Victoria Montou, whom he called “Aunt Toya.” They met while both were enslaved. The second was his future wife, Marie Claire Bonheur, a sort of war nurse, as described in this post, who proved instrumental in the siege of Jacmel by persuading Dessalines to open the roads so that aid, like food and medicine, could reach the city. When independence was declared, Dessalines became emperor, and Marie Claire Bonheur, empress. When Jean-Jacques Dessalines ordered the elimination of white inhabitants in Haiti, Marie Claire Bonheur opposed him, some say even kneeling before him to save the French. Alongside others, she saved those later called the “orphans of Cap,” two girls named Hortense and Augustine Javier.

Dessalines had a legitimized illegitimate daughter, Catherine Flon, who, according to legend, sewed the country’s flag on May 18, 1803. Thus, three essential women in his life contributed greatly to his cause.

In Guadeloupe, Rosalie, also known as Solitude, fought while pregnant against the re-establishment of slavery and sacrificed her life for it, as she was hanged after giving birth. Marthe Rose Toto also rose up and was hanged a few months after Louis Delgrès’s death (if they were truly a couple, it would have added a tragic touch to their story, like that of Camille and Lucile Desmoulins, which I have discussed here).

To conclude, my aim in this post is not to elevate these revolutionary, fighting, or Napoleonic-allied women above their male counterparts but simply to give them equal recognition, which, sadly, is still far from the case (though, fortunately, this is not true here on Tumblr).

I want to thank @aedesluminis for providing such valuable information about Sophie Carnot—without her, I wouldn't have known any of this. And I also want to thank all of you, as your various posts have been really helpful in guiding my research, especially @anotherhumaninthisworld, @frevandrest, @sieclesetcieux, @saintjustitude, @enlitment, @pleasecallmealsip, @18thcenturythirsttrap, @usergreenpixel, etc. I apologize if I forgot anyone—I’m sure I have, and I'm sorry; I'm a bit exhausted. ^^

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

every time i think about them i feel like i need the memory gun

31K notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine if everyone pretended to lecture you on maths but they were convinced 1+1=3.

That's what people do with history.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

if there ever was a time to get obsessed with plastic beach it sure was that covid lockdown summer

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stanford Pines and his brother Stanley

39K notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the TimeSwap AU i need

Safe

30K notes

·

View notes