Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Hurricane and Its Impact

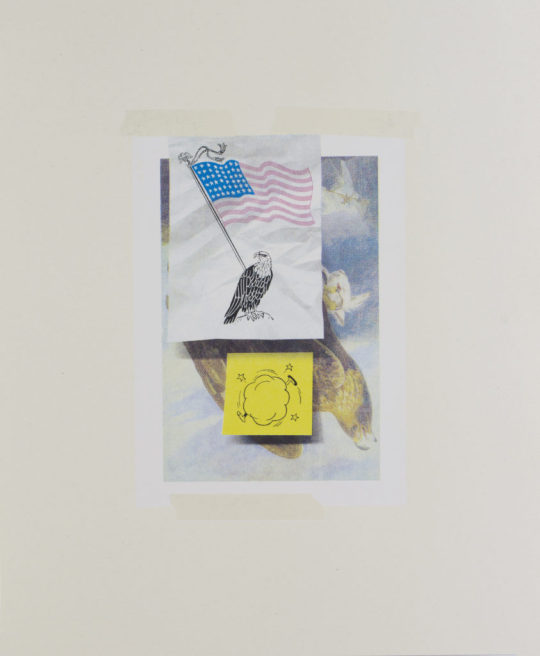

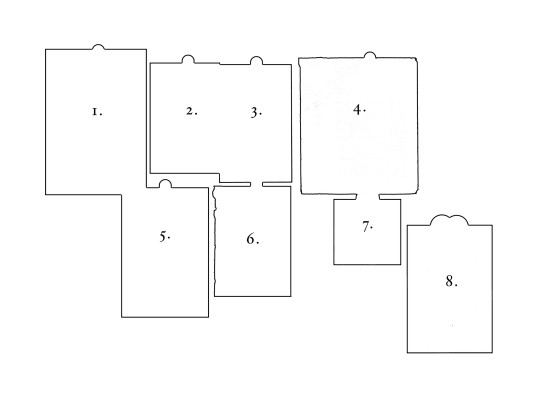

THE HURRICANE AND ITS IMPACT / 23 x 19 inches, Screen print on paper, 2016

“The Hurricane and Its Impact,” like other works in my series of screen prints on paper, “Reading,” is an attempt to layer and combine various printed sources to reflect on the past and the present and to consider or suggest possible futures. Intimations of foreground, middle ground and background are created through conventional strategies of illusionism but this happens in two distinct layers or registers—first, the depth and space captured in the photograph that functions as the print’s background and second, the illusionism of the trompe l’oeil elements that sit atop this in a second shallower space. The photographic time of the background image, depicting a man and child surveying an arctic scene, represents an instant when a camera’s shutter clicked and captured an image on celluloid. This moment was then re-instantiated in its first printing in a vintage book and finally revisited or accessed again in my print, where the trompe l’oeil additions point toward other meanings possible when time and history are kept open for reevaluation and study.

The trompe l’oeil elements here are a torn sheet of Christmas wrapping paper, adorned with a swirl of top-hatted snowmen, and a grayscale image of a hurricane torn or cut from a textbook. The promise of increasingly extreme weather caused by climate change is made to loom over the original scene (which I can’t help but read as a father and son). The giant glaciers they surveil now seem as transient and fragile as the Frosty the Snowman motif of the wrapping paper, designed to be ripped off and discarded. The hurricane image, an aerial photo of an historical weather event, is held up with a depiction of a pushpin, implying it could be replaced by an image of another, newer hurricane. The father and son may have been simply marveling at the vast arctic landscape, but I imagine the father telling his son about this landscape, facts about its long history, its harshness and brutality. His original lesson, the moment of its telling fixed on film, would certainly sound different today, the monolithic bodies of ice seeming more fragile and temporary, more temporal. There is no such thing as timelessness, nothing immune to entropy or decay and no story or lesson is final. “The Hurricane and Its Impact” suggests the importance of being open to new facts and information in an ever-changing world.

0 notes

Text

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE / 23 x 19 inches, Screen print on paper, 2016

John James Audubon’s series Birds of America is an important benchmark in both American illustration and ornithology, its place secure alongside other expansive, ambitious projects of the 19th century such as Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass or Henry David Thoreau’s On Walden Pond. But despite this pedigree, there’s something uncanny about Audubon’s illustrations—the birds, depicted in their natural habitats, carefully observed, masterfully rendered and often captured as if in motion, have this strange stiffness. It’s the feeling of a death mask, the viewer realizes, because these images, made before the advent of photography, were executed from taxidermied specimens. Indeed, Audubon paid assistants to obtain birds and bring them to his studio, where they were carefully posed with wires. Audubon was a wealthy immigrant, a slave-owner who spent time in prison for debt, a businessman and self-promoter who tried many occupations before finding success as an artist and naturalist. In short, John James Audubon, was a typically complicated American mess.

I began the four-color screen print on paper “Domestic Violence” a few days after Donald J. Trump was elected president of the United States. It felt like a very messy moment in American history. A rotated version of Audubon’s “Golden Eagle” forms the background of my print, and in every version of Audubon’s print, there’s a tiny felled tree that spans a chasm. The bottom edge of Audubon’s image doesn’t reveal just how deep this chasm goes or how far the fall. In some versions (including the one I’ve used), there’s a small figure of a man happily straddling the tree, playfully dangling over the abyss. Always, the titular golden eagle in the foreground has caught a rabbit, one talon sunk deep enough into its prey’s face to draw forth one fat, viscous teardrop of blood, a leporine version of Fra Angelico’s “Christ Crowned with Thorns.” The guy on the tree doesn’t seem to notice or care about the passion of the rabbit unfolding in the sky above him, but turn the print upside down, as I’ve done, and everyone is falling—rabbit, eagle, man. In “Domestic Violence,” I conceived of Trump as the golden eagle, his helmet of blonde hair as curiously unnatural as the reanimated specimens illustrated by Audubon, a simulacrum of a lush head of hair, the Wizard of Oz’s curtain. On November 9th, I thought everyone was falling.

My dad used to sometimes tell this one terrible joke after he’d get his hair cut. “I went to the barber today. The barber told me I have Audubon hair.” “Audubon hair?” “Oughta been on a dog!” Punchlines create second meanings. On top of Audubon’s “Golden Eagle,” I’ve depicted two pieces of paper in hokey trompe-l'œil. On each piece of paper is a cartoon. One cartoon appears as if drawn on a Post-It note and shows a couple fighting, their bodies obscured by a dustcloud of fists and feet. The image is lifted from Andy Capp, a long-running newspaper comic about a working-class alcoholic and his embattled wife. These characters no longer fight in the tornadic style I’ve show; they attend marriage counseling. The funnies sometimes advance with the times but shed some of their cartoonishness. The other cartoon image I’ve placed onto Audubon’s eagle is a bald eagle, here perched next to a waving flag. The image appears wrinkled, and it’s held up with masking tape. It nearly covers the rabbit’s bloody tear but doesn’t.

A canary yellow Post-It with low tack adhesive, masking tape holding up a wrinkled scrap of paper, Audubon’s flipped print sharing the same masking tape—all imply a temporary, variable arrangement. Time and gravity could separate all the parts, and like the man dancing on his log, the distance of the fall is undetermined, undefined. All the parts of “Domestic Violence” are cartoony in some way, from Andy Capp to Audubon to the patriotic clip-art. The trompe-l'œil shadows, too, are a kind of facile cartoon. The CMYK dots that flatten all the parts optically create a semblance of thousands of colors but work best at a certain viewing distance or with squinted eyes.

Ursula Le Guin wrote this on the subject of creative world-making: “An artist makes the world her world...Like a crystal, the work of art seems to contain the whole, and to imply eternity. And yet all it is is an explorer’s sketch-map. A chart of shorelines on a foggy coast.” John James Audubon made many images of avian specimens and even illustrated some species that are now extinct, but he failed at his lofty goal of recording an image of every bird in North America. In the quest for knowledge, understanding or progress, nothing is ever finished or finalized. We are always working from cartoons and abstractions, connecting things with lines of best fit.

0 notes

Text

Saturday on Tiptoes

I’m sneaking around my house on tiptoes on a Saturday, trying not to wake Elliot. Every day in November could be the last warm fall day of the year. It’s a beautiful day in November, but we haven’t left the house. Elliot is cutting teeth, and he’s not happy. He’s tired and hard to keep happy, harder to put down for a nap, hard to keep napping. I sneak out for a cigarette, carefully turning the doorknob. I have to use my foot to keep Macho from escaping outside with me, and I shut the door behind me as quietly as possible. Someone has been on the porch, leaving behind a postcard: “Vote Clinton and Feingold, November 8th.”

This coming Tuesday is Election day. Later today, I plan on meeting Becky after work, but we’ll see if Elliot cooperates. If everyone is up for it, we’ll all take a number 30 bus downtown, where the Milwaukee Zine Fest is being held at the Central Library. It’s the second year in a row I haven’t tabled. Between parenthood and graduate school, it’s not a priority. Anyway, I haven’t printed a new zine in almost three years. At one time, I was making three books a year. It would be easier to travel if we had a car. I guess we could get an auto loan, a risky move on our budget. Our young family feels like a statistic, part of the rotting out of the American dream. We’re waiting to hear if we’ll be accepted on BadgerCare. Maybe that’ll help pay down some of our medical debt.

I slip back inside, wash my hands, apply hand sanitizer, change my shirt. Plan to quit smoking when the snow comes. Or before Elliot is old enough to remember me smoking. We’re so proud of him, even though he’s just 8 months old. It’s hard being a baby. There’s five sharp, little milk teeth now peaking above his gums. If he can deal with that, I can quit smoking, for him, for myself, for us.

I tiptoe to my bedroom (Elliot’s asleep in his room). I’m looking online for more information about Robert Rauschenberg’s “5:29 Bayshore,” a large, multi-colored lithograph from 1981 that I saw two weeks ago at Marquette University’s Haggerty Museum. I find three separate listings for prints from the edition of 30 for sale on the websites of auction houses. One website’s estimate: 8,000 – 12,000 USD. Another estimate: 10,000 – 15,000 USD. Another: 20,000 - 30,000. That’s a big difference, the difference between 8,000 and 30,000 dollars, but also not such a big difference because neither seems like a real price for a piece of paper. I say this as a printmaker and as someone who would like to make a living as a visual artist. And I say this as a fan of Rauschenberg.

I’m looking for more information on “5:29 Bayshore” because I recall Lynne Shumow, Curator of Education at the Haggerty, saying the print was inspired by a train commute Rauschenberg regularly took at the time the print was made. I’m trying to find more about this anecdote, but all I find is three auction listings, three ranges of prices. The story of the train commute seems small and human. Robert Rauschenberg on a train. Robert Rauschenberg as a man on a train. I attended a lecture a few weeks ago by Maria Gaspar, a Chicago artist whose work advocates for prison reform in the Cook County Jail. Her 96 Acres project was a recent recipient of a grant from the Rauschenberg Foundation. According to Gaspar, the foundation has been awarding more money of late to social justice projects like hers. The 96 Acres project is ambitious but the work is also often small and human and humane, always aware of the emotional and personal costs of incarceration.

I’m looking for more information on “5:29 Bayshore” because it reminds me of the prints I’m working on at the moment. Where could I get such a big piece of paper? What would I put on it? What story am I trying to tell? And whose story?

In thirty-five years, if one of my prints lives on in a museum collection or an auction house, I hope there is more than a price attached to it. I hope for a rich history of discussion, scholarship, thinking. My most recent prints are multi-color screen prints, sometimes big but not Rauschenberg big. In them I examine the history of the environmental movement as it has been recorded in print—books, ephemera—trying to locate something that has contemporary resonance, trying to resume conversations that started decades earlier. I approach Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson (both dead) as peers whose concerns live on. I would like to talk to Robert Rauschenberg this way, but I feel stifled by his fame and stratospheric posthumous valuation. I hope that my prints are not dead-end conversations. The material value we place on objects is a topic ripe for discussion, but is it an interesting discussion when a dollar sign is a punctuation mark?

Q: Why is election day a Tuesday in America?

A: Because it can’t be a Sunday (because that’s the Lord’s day). And because a rural farmer needs a day to travel to the nearest polling place, it can’t be a Monday. So Tuesday it is. (Wednesday is market day, another holy day not to be encroached upon).

This system was established in 1845, when humans in America could be bought and sold as property.

On Tuesday November 8th, I will vote in a US presidential election for a fourth time. It will be the second time I’m casting a ballot since Elliot’s birth, so this time feels different. When I voted in the presidential primary, I stuck an “I Voted” sticker on his sleeping head and took a picture with my phone. He was less than two months old. Now he’s almost nine months, his whole life still yawning out ahead of him. I tiptoe around the house, trying not to wake him.

In my prints, whose story am I trying to tell? And to whom am I telling that story? I mine the past for material, look to dead writers for inspiration. But I want to talk about the future, about the world Elliot will live in (the one I hope he will live in, a just world). I was looking for more information on Robert Rauschenberg’s “5:29 Bayshore” because I was intrigued by a story of Robert Rauschenberg on a train, looking out a window, collecting images in his memory as they flew past (into the past), but looking ahead to his destination. Perhaps as the train pulled into the station, he already had an image in mind, an idea for something new.

0 notes

Text

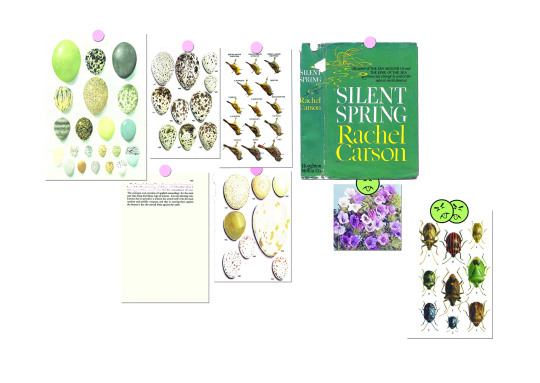

Reading Rachel Carson

1. One of the oldest children’s nursery songs in English to come down to us today is “Cock Robin.” The first written record of the song dates to the 18th century, but it was certainly sung in some form in the 15th century or earlier. A stained glass window from the 15th century depicts a robin killed by an arrow. The song begins immediately after a murder (“Who killed Cock Robin?” is the first line), moves swiftly to an inquest (“Who saw him die?”), and ends at a funeral where various animals, chiefly birds, all play roles in the mourning and burial. The darkness and solemnity of a song ostensibly for children is striking to modern ears.

2. The European robin has relatively large eyes and starts to sing early in the morning.

3. In Medieval and early Renaissance painting, multiple events could be depicted at once in a serial fashion. The world of these images reflected God’s omniscient vision of history, not the human-centered illusionism of the High Renaissance.

4. “Like the Robin, another American bird seems to be on the verge of extinction. This is the national symbol, the eagle. Its populations have dwindled alarmingly within the past decade. The facts suggest that something is at work in the eagle’s environment which has virtually destroyed its ability to reproduce. What this may be is not yet definitively known, but there is some evidence that insecticides are responsible.”

5. Accumulation of the chemical insecticide DDT in the bodies of birds often caused the production of eggs with thin shells that would be crushed during incubation. Birds are excellent, though imperfect, indicators of environment health.

6. In Fra Angelico’s tempera painting of the Biblical Annunciation painted circa1433-34, a dove representing the Holy Spirit is surrounded in gold, hovering above the Virgin Mary. The words of Gabriel unspool from the angel’s mouth in three lines like scrolls (also gold). In the background, Adam and Eve are being expelled from the Garden. The immaterial (words, spirit) is made physical and all of history is compressed into one moment.

7. According to a traditional English nursery rhyme, the number of magpies (or sometimes crows) one sees determines good or back luck. Taking the form of a counting song, it typically begins, “One for sorrow, two for joy/ Three for a girl, four for a boy/ Five for silver, six for gold/ Seven for a secret never to be told.” While regional variations to the rhyme exist, common to all versions is the notion that a lone bird is a harbinger of bad luck.

8. I read a picture of a bird right-side up as alive, a picture of a bird upside down as dead. I try the trick with images of other animals, a page from a book on insects, but the effect is less pronounced.

0 notes

Text

Aldo Leopold, Architecture and Fire

There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot. — Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

My love is a building, which is on fire. — Talking Heads

In the fall of 2011, I took a bus to Madison, Wisconsin to sell my books at The Madison Zine Fest, an annual event I’d exhibited at the year before. I filled my messenger bag with so many of my books I didn’t save room for a change of clothes. I slept on the floor of my brother and sister-in-law’s house. I arrived at their house pretty late but I was happy to finally meet my newest nephew, Alex. It was past his bedtime, but his mom carried him downstairs in a zip-up sleeper, bleary eyed and teetering on the edge of either sleep or tears. I like to think baby Alex smiled at me, just a little, before he went back to bed. I can’t remember, so let’s say, yes. He was brand new then. Now, he’s six, an awesome boy who still fights bedtimes.

In 2010, the Madison Zine Fest was held at the university’s main library. Though a part of this huge state institution, the library was the perfect venue, I thought, for a festival celebrating DIY publishing. Artists and writers sold books on sometimes esoteric or marginal topics surrounded by old books, old carpet, old electrical outlets taxed trying to accommodate the latest technology. A year later, the event was in the new student union, just across the street from the old student union and perpendicular to that old library.

The building, the new student union, had just opened that fall semester, and it wasn’t being used much yet. The old union is still open, still bustling, useful. The new one, a gleaming monument to somebody’s money, a building made to be made and not so much to answer a need. It was brand new but outfitted in autumnal oranges and browns, flagstone and brick decorated with leaf motifs, a steroidal hunting lodge aesthetic with Wi-Fi and a coffee shop. My brother dropped me off, and I set off in search of that coffee.

The coffee shop, brand new, was called Prairie Fire. A pretty good name for a coffee shop, I guess, but I thought immediately of Aldo Leopold, naturalist and writer, the most famous (to me) emeritus faculty of The University of Wisconsin-Madison, who died fighting a fire on a Wisconsin prairie. Am I alone in feeling like this is in bad taste? Yes, probably. I ordered a large, black coffee.

Aldo Leopold didn’t actually die fighting a prairie fire. He did but not like you think. He had a heart attack while helping fight a fire on his neighbor’s property, and the fire likely rolled over his body after he’d fallen in the grass. In his work and his writing, Aldo Leopold advocated for an ethical use of resources, an enlarged definition of conservationism that he called the land ethic. "The land ethic,” he wrote, “simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals.”

The fire in which Leopold died was not the first he’d encountered, making it all the more unlikely he perished in an out of control blaze, and he understood the important role of fire in prairie ecology. Elsewhere, he wrote of his Midwestern home: “In the 1840’s a new animal, the settler, intervened in the prairie battle. He didn’t mean to, he just ploughed enough fields to deprive the prairie of its immemorial ally: fire.” Leopold argued thoughtfully for nature as a complex web of relationships, in which humans should act as codependent players rather than masters. Aldo Leopold died fighting a prairie fire at the age of 62.

The zine fest was in a spacious ballroom, natural light streaming through massive windows. But sales were slow. No crowds like the year before in the library. Few people seemed to be using this new building on a Saturday morning. I made conversation with a cartoonist seated next to me. We talked about Aldo Leopold a little and about the naming of coffee shops, about architecture and the names on buildings. He had studied at Madison, lived in the suburbs, and agreed he wasn’t sure why this building was built or why it was adorned like a cabin, like the luxury version of Leopold’s hobby farm. I decided to leave the event early and meet up with my brother and his oldest son. It was a beautiful fall day. The best zine fests are bustling, warm. This felt vacant and cold. The venue was wrong; I know that much. I’ve heard the festival has since moved back to the library, but that was the last year I attended.

0 notes

Text

Reading Rachel Carson, Worrying

“The ‘control of nature’ is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man.” –Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Macho is in the foyer, scratching at the front door, stretched full length and meowing. Outside on the sidewalk is another black cat with green eyes, Macho’s doppelganger, a cat we call Outside Macho. Outside Macho crosses the street and disappears into the alley. Since we moved in a year ago, Macho hasn’t been further outside than the front porch. What he thinks of Outside Macho, we aren’t sure, but he knows about the other, wilder cat.

Through the front window, I’ve seen Outside Macho kill a bird in the tall grass of the neighbor’s yard. What our Macho would do on the other side of the door, we aren’t sure.

I’m standing on the east bank of the Milwaukee River, in the woods. My son Elliot, six months old, is strapped to my chest, his head just below mine. This morning, I accessed an online database of Milwaukee homes which might have water lines containing lead. Our address, and every address on our street, is on the list. The mayor’s office advises concerned citizens to install water filters.

I hold my phone at arm’s length and take a photo of us by the river. I look at the screen and see Elliot smiling back, looking healthy and happy. I worry. Our home is a thin membrane pierced in a million places. I worry about the water from the street, the food from the grocery store, the conditioned air coming from the vents all summer. Our cat wants to be wild. I want to pull everything close and hold it tight.

Rachel Carson’s landmark 1962 book Silent Spring is famous for leading to the 1972 ban of the synthetic pesticide DDT. Silent Spring is a plangent call to arms, arguing that chemical solutions aimed at increasing human comfort never affect only their intended targets but carry wide-ranging dangers that echo through an ecosystem. The book was famously mentioned by President John F. Kennedy in a press conference the year of its publication and is widely credited with inspiring Congressional revisions to laws governing the labeling of pesticides. Silent Spring, like Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac (especially its concluding chapter “The Land Ethic”) or Buckminster Fuller’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, are viewed as milestones leading to the formation of the modern environmental movement.

Reading Silent Spring in 2016, while Elliot sleeps (when I do all my reading), Carson’s warnings are as urgent to me as they must have been when the book seized the popular imagination in the early 1960s. The book is conspicuously absent from the catalog of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Golda Meir Library. I find a few biographies (some nearly as old as Carson’s seminal tome, published two years before her death). The library holds a handful of critical writings, most of which deal with the book as milestone, not living text.

When I read Silent Spring, I think of Monsanto, Round-Up, global warming, avian flu, superbugs. I worry, and I feel a bit like a crackpot, which might be the way we’re conditioned to feel when we name and list our fears like this rather than press them down and away. Life is comfortable, mostly, please don’t worry.

I turn to the Internet, trying to find other contemporary readers for whom Rachel Carson is still a bellwether in an age perhaps more uncertain than her own. I find an article from 2012 in The New York Times, “How ‘Silent Spring’ Ignited the Environmental Movement” by Eliza Griswold. Griswold draws parallels between Carson’s fight and a current class action lawsuit against a coal-fired power plant. I’m reassured, but I find one phrase troubling—Carson is called “the nun of nature.” A superlative, to be sure, but confusing. It’s my first encounter with this appellation, but a Google search offers many more, never with a citation. That’s just what she’s called, I guess. I begin puzzling over what nun might mean in Carson’s case. “Nun” can signify devotion to a cause, sure, but also a vow of celibacy. I’ve found other references, though, to a “female companion” who shared Carson’s life until her death, which always scans as a genteel gesture towards a queer life that biographers would rather gloss over. “Nun of nature” increases the unsexing of Carson. It places not only Carson’s writing in a secure, inoculated past-ness but Carson as well, not a living woman but a ready, safe icon.

I worry. As a new parent, I have a rich, new litany of worries and fears. Often, Becky and I feel like we’re worrying alone or worrying our worries for the first time in recorded history. Elliot’s first cold is the first cold to ever befall babykind.

Talking to other parents helps, people who have been here before. This is the way I read Rachel Carson. Why I read Aldo Leopold. I don’t read historical texts for a past that is a closed circuit but for something I can access. I’m listening for echoes. Echoes that say that the worries go on but so does the fight and the struggle.

Hopeful words: “Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature -- the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.”

1 note

·

View note