farrellleto

763 posts

XanXan has been a patrochilles fan for ~2300 slutty slutty years ☆ history memes & interesting stuff ☆

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

prometheus: hot take,

the greek gods: no give that back

94K notes

·

View notes

Text

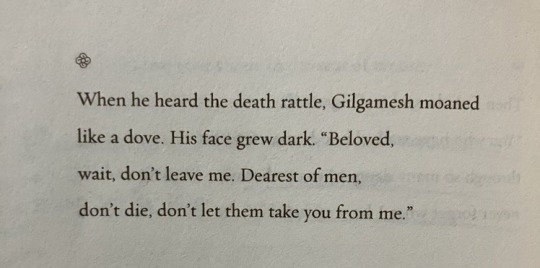

this is going to have me on my hands and knees dry heaving

95K notes

·

View notes

Text

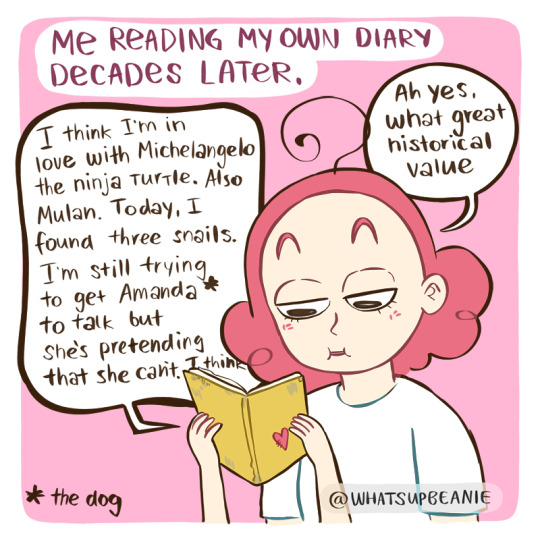

ok but the ancient hellenic child rambling about Achilles and petting the family dog is such an Alexander the Great image that I had to say something

I was reading one of my childhood diaries the other day and there was a whole paragraph saying how hopeful I was that my writing will help the archeologists in the far future. Then it proceeded to describe my lunch that day and how my dog was probably secretly able to talk.

82K notes

·

View notes

Note

What’s the most underrated pre-Alexander king of Macedon?

Easy. Perdikkas II.

He kept Macedonia independent throughout the long-ass Peloponnesian War. He changed sides 11 times to do so, and Thucydides kinda hated him. So be careful about what Thucydides says about him in his history. It's NOT unbiased. Thucydides wound up exiled due to losing Amphipolis for Athens, which he blamed (partly) on Perdikkas, although it was Brasidas (of Sparta) who orchestrated that.

But Perdikkas managed NOT to be obliterated by either the Athenian or Spartan superpowers--nor the powerhouses of Lynkestis or Elimeia either. Remember, at that point, they were independent Upper Macedonian kingdoms. Apparently, the Elimeian cavalry was even superior to the Macedonian for a while.

Alexander I (Perdikkas's father) was more colorful, and overall probably did the most (before Philip II) to push Macedon forward. And Archelaos (Perdikkas's son) might have topped Alex I, if he hadn't got himself murdered in 399.

BUT ... the most underestimated/underrated king?

That's my man, Perdikkas Alexandrou!

If you can read German, here you go. Best biography on him.

If you can't read German, but can read English, an older but still solid work on Macedonia generally:

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Re-post (Tumblr a bloqué cet ancien post soi disant qu'il est explicite!)

revue internationles:

- public 29 novembre 2004 (france) /

- choc 2 decembre 2004 (france) /

- B decembre 2004 (hollande)

collection personnelle

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colin Farrell and Jared Leto using the same metaphors.

#screaming honestly sure it could be a coincidence it's a pretty standard metaphor but how many coincidences until it starts to feel real#cuz it started to feel real in like 2003 and that was like. 30 love songs prior

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

This ship. Second to none.

RY X - Lençóis (Love Me) [Notre Dame Remix]

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

115 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ivory Sculptures of Alexander the Great & Philip II of Macedon from royal burial tomb of Philip II

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

The earliest depiction of Jesus, engraved by someone mocking their friend for believing in him, giving him a donkey head

200AD

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Human beings exist for the sake of one another: so, either teach them or endure them. Οἱ ἄνθρωποι γεγόνασιν ἀλλήλων ἕνεκεν: ἢ δίδασκε οὖν ἢ φέρε. --Marcus Aurelius, Meditations VIII.59

507 notes

·

View notes

Text

i know the minotaur's labyrinth was almost certainly actually a maze but it's really funny to imagine theseus was just so fucking stupid he couldn't even find his way out of a unicursal, non-branching path without ariadne's ball of string

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

You are not immune to men's thighs

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Netflix's Alexander the making of a god: pretty rad actually

My judgement: 8/10

While I'm not a history professional but a humble Alexander-the-great enthusiast, and I must admit I cannot judge the historical accuracy of all bits of information presented in the documentary either, I'm still impressed by the overall production as well as the producers' intention.

Firstly, I appreciate the presentation of a "non-Europe-centric" world at the time of ATG (which is objective since this was a pre-colonialism era, where multiple powerful nations outside of Europe existed, such as ancient Persia, ancient India and ancient China) and ancient Persia is portrayed as a strong rival instead of an uncivilised foreign hostile (I laughed every time the Greeks or Persians refer to each other as "barbarians" because this was how almost every ancient kingdom viewed the others, which is funny from a modern perspective). In the same respect, Darius is given a rationale for his motivation and shown as a worthy opponent.

In regards to acting, to me this series has the most accurate casting choices so far, and even if Buck Braithwaite (the actor portraying Alexander) doesn't deliver the sort of grandiose performance one would expect to be suitable for a figure like ATG, I'm moved by how human and nuanced his version of Alexander feels.

I'm definitely pleased with how truthful the relationship between Alexander and Hephaistion is portrayed, it's probably the very first time in human cinematic history that we see a portrayal like this (confettis!).

Regarding the low ratings, I'm aware that there are primarily two concerns resulting in this: 1) conservatives being deeply upset about Alexander being explicitly bisexual. I disregard such opinion completely since I know it is decidedly conservative which I don't agree with; 2) a neutral concern about the show not offering enough historical facts / not being accurate enough. As mentioned above I'm not a history professional, so as a common viewer I can only "blindly" trust the scholars being consulted.

In fact, I found the ratings of nearly all the ATG cinematic productions to be relatively low, from the 1963 Alexander, to the 2004 Alexander, and to this Netflix production. I understand that people throughout the ages have had mountainous expectation for any portrayal of ATG since he was not only a truly competent ruler but also a cultural legacy. And there's also another layer: even though he had accomplished monumental success as a conquerer, nonetheless his conquering brought wars and suffering to the civilians. Although the geopolitical dynamic then was different from that of now, meaning the countries he conquered were not considered "less developed", still you CANNOT tell the contemporary audience, some of whom are descendants from those conquered countries, who are people of colour, that Alexander's conquering of their countries was a natural result of social Darwinism, that these countries deserved to be conquered and casualty didn't matter – it's insensitive. As a POC myself, in my eyes Alexander was very much a hero of his time who had some greatness that all people can aspire to, but his military exploits are morally debatable according to modern standards (I don't hate him, I almost named my cat after him, I only want to view him as dialectically as possible). In sum, positioning the moral of his story for the post-colonial modern audience is tricky. Therefore, this Netflix documentary is the best reimagination of him, at least in my personal opinion.

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would Alexander have really married Cleopatra Eurydice? He seems to have respected her enough despite her relation to Attalus- some sources say when removing her statue from the Philippeum he transferred it to another respected place in Heraion. Did they get along personally? How would their marriage have changed matters, if at all?

Okay, first, I believe we have a confusion/conflation of Eurydikes. The one from the Philippion is Philip’s mother, wife of Amyntas III. Her statue was never removed out by Alexander, so I’m unsure what the asker is referring to? The statues were lost over time, but we have the statue bases, and descriptions of the monument. See especially Elizabeth D. Carney, “The Philippeum, Women, and the Formation of Dynastic Image,” in W. Heckel, L. Tritle, and P. Wheatley (eds.) Alexander’s Empire: Formulation to Decay (Claremont, CA, 2007) 27-70. For Eurydike herself, see Olga Palagia, “Philip's Eurydice in the Philippeum at Olympia,” in E. Carney and D. Ogden (eds.), Philip II and Alexander the Great (Oxford 2010) 33-41.

“Eurydike” became a dynastic name, so it keeps popping up among Argeads (and later). Philip’s mother was Eurydike, as was his daughter, wife of Philip III Arrhidaios: (Hadea) Eurydike. Also Kleopatra, niece of Attalos, took the name Eurydike when she married Philip. But she was never in the Philippeon. Philip’s only wife represented there was Olympias, mother of his heir, Alexander. Amyntas III and Eurydike appeared as his parents.

We have no idea if Alexander shared more than a few words with Attalos’s neice. Given her uncle’s hostility towards him, he would likely have minimized contact. Also, timing was against it. Alexander left on the heels of the marriage, was gone 6 months to a year, then likely kept his distance after his return. While Macedonian women were not as sequestered as in Athens, men and (respectable) unrelated women still didn’t mingle freely. If he did interact with her, it would have been when visiting the women’s rooms to see his sisters, with plenty of women present. If marrying a dead father’s widow had precedent, an affair with the wife of one’s living father was another thing. Alexander knew his mythology, and would’ve had no desire to be Hippolytos.* After he took the throne, he had to leave relatively quickly to settle affairs in the south…and she was (likely) dead before he returned.

As for the marriage… this was suggested by my colleague, Tim Howe: “The Giver of the Bride, the Bridegroom, and the Bride,” in T. Howe, S. Müller, and R. Stoneman, Ancient Historiography on War and Empire (Oxbow, 2017) 92-124. Nothing in the ancient sources says Alexander planned such a marriage BUT marrying the wife (especially if young) of the former king wasn’t novel in Macedonia; Archelaos did the same. It was accepted practice generally.

The titbit that might suggest Alexander did plan to wed Kleopatra-Eurydike … Olympias murdered her.

Now, ignoring Justin’s account of a son Karanos, which is wrong (for reasons I don’t have time to go into), Kleopatra-Eurydike’s child was a girl (Europa). That means Kleopatra had no power in the women’s rooms after Philip’s assassination. So why the hell would Olympias kill the infant (and her, by extension)? Revenge alone?

Possibly. Revenge, especially for a slight to timē (personal honor), was a perfectly respectable reason to kill someone. “Turn the other cheek,” or “When they go low, we go high,” is a very Christianized view. But an even better revenge would have been to let her live to raise an extra daughter under the king her uncle had insulted and schemed to replace. Philip had 3 prior adult/almost adult daughters. A 4th, well over a decade from marriageability, was a day late and a dollar short. She could expect a miserable existence in the Pella palace where she was no threat to Olympias.

Unless Alexander planned to marry her in a diplomatic solution to suppress Attalos’s faction, and secure Parmenion’s support. (Attalos had married Parmenion’s daughter.) I strongly suspect Philip’s final marriage was not the midlife-crisis love match Plutarch/Diodoros present, but an attempt to deal with push back in his latter years. Alexander may have decided that marrying the girl was the best way to deal with it too.

And if Alexander did plan to marry her, she was a threat to Olympias’ influence. This isn’t necessarily jealousy. Olympias may have decided that wooing the snake wasn’t sound policy. Remember that Alexander was barely twenty and Olympias would have been between 36 and 38, with oodles more political experience. While sure, her move was self-serving, it also may have been sound policy to keep her son from the match. (Two things can be true at once.)

Alexander need not have publicly declared an intention to marry his father’s widow; he had bigger fish to fry in the immediate aftermath. Yet if he’d discussed it privately, his mother may have moved to eliminate the possibility while he was out of the country. The brutality of the murder certainly suggests a vengeance theme.

Incidentally, while the death of Europa at Olympias’s hands (and Eurydike’s subsequent suicide) is not securely dated in our sources—except that Alexander wasn’t in Pella—it almost certainly occurred in the first months after Philip’s death, during Alexander’s first trip into the Greek south, to shore up support for the Persian invasion and re-ratify the Corinthian League.

As for how their marriage may have changed things…it would almost certainly have put Alexander under the thumb of Attalos-Parmenion. We can see, in the appointments of his two sons, that Parmenion alone held great sway in Alexander’s early years—but at least he wasn’t an in-law. For once, Olympias and Antipatros were likely on the same side. (Antipatros and Parmenion weren’t precisely friendly.) If, as I suspect, Philip made that marriage for political reasons, it suggests the Attalos faction—whatever that entailed—was strong enough to force Philip’s hand before leaving on a probable long-term campaign. That means Attalos was powerful. And a 20-year-old Alexander was no match for him, even if adolescent arrogance may have made him think he was. Olympias may also have decided/suspected that the Attalos-Parmenion tie wasn’t as strong as Alexander feared—which proved to be true. When push came to shove, Parmenion allowed Attalos to be eliminated on Alexander’s order.

Arrian glosses over all this. I wish we had the first two books of Curtius, who likely covered the story of Alexander’s accession in more detail. It would provide more clues. Attalos sorta comes out of nowhere at the end of Philip’s life. Although Diodoros’ account of his reign is so truncated we don’t know the marshals under Philip well, so he may have been around longer than it seems.

————-

* Alexander knew his mythology. Theseus’s second wife, Phaidra, was reportedly cursed to conceive a passion for her (more age-appropriate) son-in-law, Hippolytos. Yet Hippolytos had pledged his virginity to Artemis, offending Aphrodite, who was behind the curse. When Hippolytos rebuked poor Phaedra’s advances, she suicided, leaving a note implicating Hippolytos (for rape). As punishment, Theseus asked his father Poseidon to kill his son. While out in his chariot, a sea monster spooked the horses, he fell out the back but got tangled in the reins, and they dragged him to death. A variation exists in which Aisklepios brings him back from death but Hades is so offended/(worried) by this power, he asks his brother Zeus to strike down Aisklepios by lightning…which he does. One of the few cases of a god dying. (They’re immortal, yes…but can be killed; it’s just that few things can kill one. Being fried by lightning will do it.)

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dr. Reames!! Oftentimes I see it mentioned that Alexander’s Persian campaign was framed at the time as a revenge against Persia for previous wars against Greece. And so, for example, the burning of Persepolis could be interpreted as payback for the burning of Athens.

But how accurate is that actually? I can only suppose that the top echelons of the Macedonian military establishment didn’t really feel that strongly about Greece as a whole (as Greece wasn’t a unified country like today), but had to frame it as such to disguise what could be seen as a shameless offensive land grab.

Even so, Alexander knew his propaganda. Was there a general feeling among the people of Greece and the rank and file troops that this campaign was a revenge for the previous wars Persia waged against Greece? Some sort of unifying spirit, ideal? And Alexander exploited this for his benefit? Or is this idea of a Greece vs Persia conflict a complete fabrication of misinterpretation?

The idea of a “Revenge against Persia” campaign was part of 4th century political discourse before Alexander, or even Philip. The question was who would lead such a campaign? Naturally, Athens thought they should, but after their defeat in the Peloponnesian War, didn’t have the military mojo. And even in Sparta had opposed the Persian invasion (alongside Athens), he owed her success in the Pel War to Persian assistance, so that was a problem. Thebes as a potential leader was even worse, as she’d Medized (went over to the Persians), so hell-to-the-no would she be appropriate.

Isokrates was probably the first to suggest it be Philip, as his star was rising. Yes, Macedon had also Medized, but Alexander I had been a clever man who played both sides against the middle and was able to burnish his rep after the war as “having no choice, and see? I helped Athens by providing her with timber for the Greek fleet”…if at, we’re sure, a substantial sum that benefited Maceon. But Macedon resented Persia too and had been a victim! It provided the plausible deniability needed to elevate Philip as leader of the Go-and-get-Persia campaign.

Of course Athens was not keen on this. She still thought SHE should be leading the vengeance war, as she won the two most significant battles of the Greco-Persian Wars (Marathon in #1 and Salamis in #2). That Philip was out-maneuvering her at every turn for the hegemony of greater Greece was additionally galling.

When Philip decided to invade Persia is a point of great contention, but I think he had it in mind by the time of his extensive Balkan campaign (c. 341/40/39. when Alexander was left in Pella as regent). Much of that was to secure the Black Sea coast and conquer Perinthos and Byzantion (Athenian allies) in order to secure a bridgehead to Asia. He may have believed that the Athenian Isokrates’s oration letter to him was indicative that Athens could be won over as an ally, in order to provide the ships he needed but didn’t have. He knew Demosthenes a problem, but may not have believed fear of/resentment against Philip himself would unite Thebes and Athens (inveterate enemies) to oppose him at Chaironeia.

But that’s how it went. Philip won anyway and created the Corinthian League, whose purpose was the invasion of Persia and vengeance for the earlier Persian invasion of Greece. Was that Philip’s primary motivation? Oh, hell no. He wanted the MONEY/loot (and glory). But a campaign of retribution put a better face on it, and justified his usurpation of the Athenian navy, which he absolutely had to have to be successful.

When Philip was assassinated, Alexander simply took up where his father left off. He literally told the Corinthian League (when he reconvened them not long after Philip’s death), “Only the name of the king has changed….”

So yes, the propaganda wasn’t invented by Alexander, or even by Philip, but they used it to very good effect, as it allowed them to demand allies (and BOATS). Alexander didn’t dissolve the alliance and release those troops until after Darius’s death. And even then, he offered good pay to stay on with the rest of his conquests (which many did).

10 notes

·

View notes