Text

Mark Rothko

September 25, 1903 – February 25, 1970

"I realize that historically the function of painting large pictures is painting something very grandiose and pompous. The reason I paint them, however ... is precisely because I want to be very intimate and human. To paint a small picture is to place yourself outside your experience, to look upon an experience as a stereopticon view or with a reducing glass. However you paint the larger picture, you are in it. It isn't something you command!"

209 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Along the Coast (1958) dir. Agnès Varda

26K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Iwajla Klinke (German, b. 1976)

Untitled, From the Series Bescherkinder,

Lusatia, 2014

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

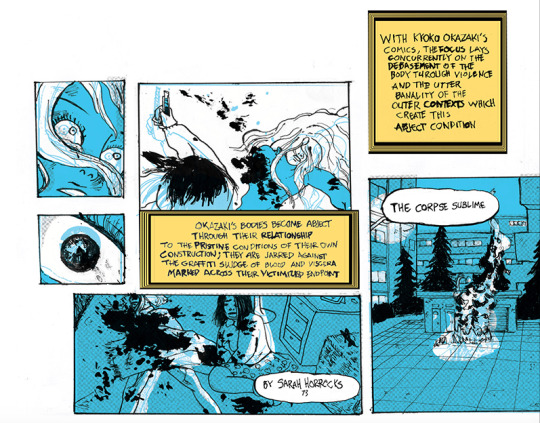

Pink by Kyoko Okazaki

Hi, I’m Jacob Shapiro and I run Fantom Comics in Washington, DC! I was asked to guest curate this page with comics from my personal collection that matter to me. My third post is about the oldest book I’ll write about this week, and the only manga: Kyoko Okazaki’s seminal 1989 comic Pink.

I didn’t grow up reading manga, or even really watching any anime aside from Pokémon. For the longest time, I wrote off manga as mostly being about magical children punching things. It wasn’t until a roommate of mine in 2014 forced Junji Ito’s horror opus Uzumaki into my hands that it finally hit me–for all the weird indie American comics I read, the same types of things are being created in Japan!

Coincidentally, that was the year I started working at Fantom, so suddenly I had a whole manga library at my fingertips, and I dove in headfirst. From Ito to Taiyo Matsumoto’s melancholy slice-of-life Sunny to surrealist Inio Asano’s Goodnight Punpun to gay manga icon Gengoroh Tagame’s My Brother’s Husband (which has already been written about on this blog!), at this point I’ve realized how wrong I originally was about manga. These are many of my all-time favorite comics.

Pink is about an office worker in her early 20s who works as a call girl at night to support her pet crocodile… and things get dark. I had seen it on the shelf at Fantom for a while alongside Okazaki’s later work Helter Skelter, but I didn’t really pay it any mind until I read a piece by comics critic/creator Sarah Horrocks (aka @mercurialblonde) in the now-defunct Island magazine that opened like this:

Holy shit, right?? There seemed to be a huuuuuge dichotomy between the frilly cover of Pink and the body horror Horrocks was describing in her piece–total tangent, but Horrocks’ fusion of Okazaki’s original panels with her own art on top of them to analyze them is such a genius marriage of analysis and art and Sarah deserves more credit for doing something no one else in the industry is doing right now. She’s written a ton about Okazaki, more eloquently than I ever could. Anyway, it made me finally sit down and read Pink.

And Pink encapsulates all of this dichotomy. Okazaki also worked as a fashion designer, so the work pays close attention to aesthetic and is firmly feminine while being unrelentingly grotesque at the same time (which reminds me of Hannah K. Lee’s Language Barrier that I wrote about yesterday). It’s also unapologetically sexual–it blew my mind that in socially-conservative 1980s Japan, Okazaki was able to be so deviant as a female manga artist and get away with it.

This is a strange comic. It’s really violent and full of nudity. But it’s also really pretty. There are few other mainstream comics that demonstrate art can be so aggressively feminine and unrelentingly violent at the same time; they’re not opposing forces, but rather completely intertwined and complimentary.

I’m on Tumblr at @aleneigen, and Fantom Comics is on Tumblr at @fantomcomics.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Consider the Vikings. Popular feminist retellings like the History Channel’s fictional saga “Vikings” emphasize the role of women as warriors and chieftains. But they barely hint at how crucial women’s work was to the ships that carried these warriors to distant shores.

One of the central characters in “Vikings” is an ingenious shipbuilder. But his ships apparently get their sails off the rack. The fabric is just there, like the textiles we take for granted in our 21st-century lives. The women who prepared the wool, spun it into thread, wove the fabric and sewed the sails have vanished.

In reality, from start to finish, it took longer to make a Viking sail than to build a Viking ship. So precious was a sail that one of the Icelandic sagas records how a hero wept when his was stolen. Simply spinning wool into enough thread to weave a single sail required more than a year’s work, the equivalent of about 385 eight-hour days.

King Canute, who ruled a North Sea empire in the 11th century, had a fleet comprising about a million square meters of sailcloth. For the spinning alone, those sails represented the equivalent of 10,000 work years.”

“…Picturing historical women as producers requires a change of attitude. Even today, after decades of feminist influence, we too often assume that making important things is a male domain. Women stereotypically decorate and consume. They engage with people. They don’t manufacture essential goods.

Yet from the Renaissance until the 19th century, European art represented the idea of “industry” not with smokestacks but with spinning women. Everyone understood that their never-ending labor was essential. It took at least 20 spinners to keep a single loom supplied.

“The spinners never stand still for want of work; they always have it if they please; but weavers are sometimes idle for want of yarn,” the agronomist and travel writer Arthur Young, who toured northern England in 1768, wrote.

Shortly thereafter, the spinning machines of the Industrial Revolution liberated women from their spindles and distaffs, beginning the centuries-long process that raised even the world’s poorest people to living standards our ancestors could not have imagined.

But that “great enrichment” had an unfortunate side effect. Textile abundance erased our memories of women’s historic contributions to one of humanity’s most important endeavors. It turned industry into entertainment.

“In the West,” Dr. Harlow wrote, “the production of textiles has moved from being a fundamental, indeed essential, part of the industrial economy to a predominantly female craft activity.””

- Virginia Postrel, “Women and Men Are Like the Threads of a Woven Fabric.” in The New York Times

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/a55592/playgirl-magazine-history/

0 notes

Link

From Stanford news:

A new student-run journal focused on art history and film studies, called Manicule, released its first issue last month.

The journal showcases scholarly and creative pieces written by Stanford undergraduate students in the fields of art history and film and media studies. The aim of the annual publication is to provoke new ways of thinking about art, enrich Stanford’s arts community and give undergraduates an inclusive outlet to share their ideas, according to the journal’s mission statement.

“We aim to write and publish pieces with style, passion, conviction and a desire to illuminate,” the mission statement says.

Carolos Valladares is listed as Manicule’s editor-in-chief, and Tabitha Walker and Samantha Wassmer are the managing editors. All three undergraduates are in the Class of 2018. The journal’s faculty advisers are art history Professor ALEXANDER NEMEROV, art history Assistant Professor MARCI KWON and GABRIELLE MOYER, a faculty member in the Program in Writing and Rhetoric.

The journal’s name comes from the Latin word manicula, which means “little hand.” This refers to a pointing hand symbol, often used in printing, graphics or signs, to draw attention to something previously ignored.

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.jungewelt.de/artikel/386635.frauenfilmfestival-ifff-zerplatzte-illusionen.html

0 notes

Text

Baya mahieddine : flowers under the jasmin. notes of music through the bombs.

Bright and contrasting colors, delicate swirls and bold lines, the work of Baya Mahieddine is well known in certain artistic circles, especially those that are interested in the history of algerian art, surrealism and modern art.

Nonetheless, it’s still a name that’s often unknown to the general public or to someone who only has a passing knowledge of art history. Which is, in my opinion, a shame that such a talented artist, and who had such a unique vision, had mostly been relegated to obscurity, when her white male counterparts, that were active in the same time as she was, often have entire courses being given on their lives and art. Books upon books have been written on Picasso, or Marcel Duchamp. Names such as Piet Mondrian, René Magritte are being remembered by history and their works are easily recognizable by the average person.

Baya Mahieddine, who simply went by the name Baya, and whose birth name was Fatima Haddad, was an algerian pictural artist who drew masterpieces that were considered to be on the same level as Matisse and Picasso at the very young age of 16 years old. Her paintings had a very distinct and recognizable style, it’s very easy to single out a piece she created. Yet, neither her art, nor her story are remembered by history (or at least, white western history) and the field of art history on the same scale as these men.

This is a story of a woman, of a country, colonisation and, hopefully, of justice.

Keep reading

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

Pool of Tears I, Kiki Smith, 2000

Etching and aquatint on paper 37.3 x 45 cm (14 ¾ x 17 ¾ in.)

2K notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Link

“In Civilization, women are objectified and treated as property—that is, owned to some degree—more than men. That doesn’t change with “sex-positive feminism". The sex-positive idea is that women can gain some degree of control by objectifying themselves. Women remain objects, but if we play it right, the reasoning goes, we can partake in more of the profits of our exploitation.“

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

Night at the museum, Nicolas Krief

101K notes

·

View notes