The name of this course’s theme, “Getting Away With Fiction”, is meant to play on two preconceptions of fiction: the first, that fiction conspires to distort reality, but has less of a claim to truth than realism; the second, that fiction is escapist. .

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

In his commentary accompanying A Story of Floating Weeds (1934), Donald Richie defines modernity in film narrative as “a style of telling which is extraordinarily concise”. He further explains, “the form [of that narrative] is the shape of the story itself, and vice versa. It’s one that elides almost as much as it includes” (14:08)*. Although Ozu created this film after the unofficial end of the silent era, his narrative and filmmaking styles were (and would continue to be) markedly subtler than both contemporary and earlier silent film. In American cinema during the silent era, many performers originally trained in popular theatre, where exaggerated acting techniques and melodramatic situations were conventional. Many works of performing arts from this period would have been appealing because they made their audiences feel strong emotions. In contrast, Ozu consciously avoided forcing emotions upon his audience. He relied on his audience’s sensibilities.

“This kind of modernism”, which Richie refers to as Ozu’s dependency on the audience’s intuition, “plus the great willingness of Ozu to elide parts of its story, to allow us to figure out things for ourselves, this is a part of modernism. The playing down of emotion, as seen in this film—we don’t get to see any, you know, violent crying scenes. We get some violent slapping scenes, but nobody really bursts into tears on camera and if they’re going to bursts into tears, then they turn off camera themselves. We don’t have to watch them. This also, I would maintain, this lowering of the emotional temperature, is very modernistic of Ozu, in that modernist works have no use for this sort of Victorian kind of displayed emotion” (16:25).

The above clip (57:25)** is one of the most turbulent scenes of the film, yet its true power comes from its tension, rather than its violence. Whereas those brief explosions of physical anger expel the tension between the characters, their competing stares bottle it up, maintaining its suspense. Otaka speaks in dialogue with Kihachi’s inability to translate his violent temper into words. This further illustrates their present discord. The similarity between Richie’s words, “figure out things for ourselves”, and Otaka’s “Just think how I feel” is fortunate; given little information about Otaka and Kihachi’s relationship before this rift, which disinclines them to explain their motivations, the audience must intuit the depth of Otaka’s jealousy. Her words, lost on Kihachi, encourage our participation in the meaning of the story.

*Time stamps indicate that the film is played with audio commentary by Donald Richie. A Story of Floating Weeds. Dir Ozu, Yasujiro (Yasujiro, Ozu). Criterion Collection, 1934.

**The above clip is taken from A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) and is shuared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Text

Following his altercation with Bernie, the camera slowly traces up Driver’s body and the trail of blood from his wound (1:36:12). After a full thirty-second pause, he blinks, which is the first movement to disrupt his lifeless appearance. Combined with the shot’s silence, this pause elevates the audience’s anticipation, as Driver’s survival is unassured. The rhythmic music slowly crescendos (meaning it gets louder), just as if Driver’s heartbeat is returning. Just as in cinematography, when an image slowly becomes visible, in sound design this amplification is called a fade-in. The song, “A Real Hero”, reminds the audience of an earlier scene in which Irene and Driver develop affection for one another, and transitions to the final sequence of the film, which alternates between shots of both of them, separately.

*The above clip is taken from Drive (2011) and is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Text

Each song in Drive is carefully chosen to invoke a mood or mental state. The above scene (1:11:31) contains both the most intimate and most distant moments for Irene and Driver. Music transitions smooth the emotional transitions between these moments. In the beginning of this clip, the combination of soft ambient music and slow motion allows the audience to forget briefly the characters’ immediate danger. As the characters step closer to the rear and overhead lights (which function practically as backlights and hair lights), the key light softens, creating the effect of a halo around Irene and Driver. The music’s ominous transition and the film’s return to normal speed precede Driver’s fight with the “Tan Suit”. Driver’s kicks and the sound of crushing bone are examples of Foley sound effects. A sound designer creates these effects synchronously with the images on screen to magnify their impression. The discordant music continues and intensifies as Driver turns to see Irene’s expression of horror. The elevator door closes, “bringing down the curtain” on their chance of being together, since this will be the last time they see each other.

*The above clip is taken from Drive (2011) and is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Text

In such scenes as the ambush of Driver and Blanche at the motel, sound is used to “break the screen plane”, to borrow the words of Stanley Alten*. Such details as the ringing sound following the shotgun blast and Driver’s breathing (1:02:25) simulate the experience of the characters for the audience, thereby drawing the audience into the action.

*p 292, Audio in Media, 9th e.

**The above clip is taken from Drive (2011) and is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Text

Irene hosts a party in honor of her husband’s return to society. The music playing in her apartment demonstrates two uses of film music. The first is source music, which is recorded music that’s part of the setting. Although we don’t see a stereo, we assume that this is the source of the music. Music can also be used to narrate the film, although it’s not really playing in the setting. This is underscoring. In the above clip (37:30), underscoring performs at least three important functions. For one, it defines the relationship between scenes. The film cuts between Irene and Driver’s apartments. The use of underscoring bridges both scenes and reinforces their comparison, making it clear that these scenes belong to the same part of the story. In another function, performed specifically by the song’s lyrics, the music tells the audience what the characters are feeling. The repeated lines “you keep me under your spell” and “I do nothing but think of you” compliment their distracted, sentimental expressions. Finally, the use of underscoring foregrounds these feelings. All of the other sounds, including the noise of the party, become distant, as the narrative focuses its attention on the characters’ inner selves, rather than the external personae they present to others. This is especially important for Driver’s characterization, given his typical stoicism. It also reveals feelings to the audience that both Driver and Irene hide from her husband. Near the end of this clip, the music switches back to source music. The music’s muffled sound describes its travel through the wall into the hallway, which is the next location of the action.

*The above clip is taken from Drive (2011) and is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Text

Often, sound effects suggest props without their appearance on camera. In the first part of this clip (34:27), we hear (but don’t see) a ringing telephone. Just its sound is enough to cue the next scene, in which Irene tells Driver the purpose of the phone call: her husband is about to be released from prison. However, the most powerful parts of this scene are the lengthy silences between them. The film includes several close-ups and two shots of the characters, shots that films frequently use to accompany a conversation. As long as films have included sound, silence has been a powerful tool*, and here it really does speak volumes about the characters’ feelings.

*pp 383 – 385 in Looking At Movies (5th e) develop this point.

**The above clip is taken from Drive (2011) and is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Text

The first nine-and-a-half minutes of Drive (2011) use Chromatics’ “Tick of the Clock” to underscore the story’s opening and the protagonist’s (known only as “Driver” in the credits) character exposition. The song transitions between a simple electronic bassline and drone. The bassline’s tempo, which is the frequency or “speed” of rhythm in music, both adds excitement to the scene and suggests Driver’s steady nerve. The opening is also remarkable for its use of descriptive and commentative sound, which are two ways sound may be used to narrate a film. Commentative sound comments upon the action; rather than just tell the story, it reveals the narrative’s intention. In this case, the sound of the announcer’s commentary (8:47) comments upon Driver’s getaway, which the narrative intends the audience to root for as it would a sports team’s success. The countdown to the end of the game suggests that Driver’s “goal” is near. As he pulls into the parking garage, the cheers coming over the radio blend into the excitement of the crowd exiting the arena. It instantly becomes clear why Driver has been following the game. The crowd’s exit covers his escape. Their noise is descriptive sound, which describes what’s evidently happening in the scene.

*The above clip is taken from Drive (2011) and is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Photo

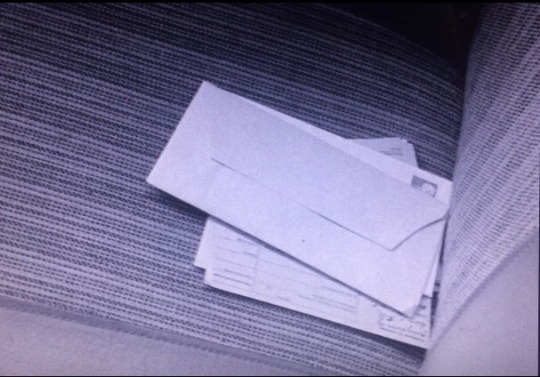

In the left (42:00) and right images (42:12), Alma curiously eyes a letter written by Elisabet to a doctor (likely, Alma’s superior). Upon reading it, Alma feels betrayed by Elisabet for repeating an anecdote about her personal life that she shared with Elisabet. Compare how the letter affects Alma with the foregrounding of the letter in Untitled Film Still #33.

*The above images are taken from Persona (1966), and are shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Photo

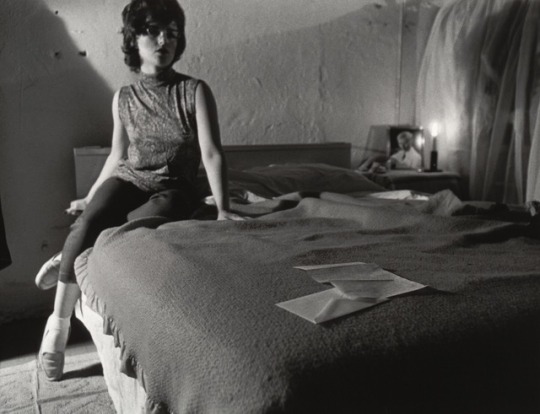

Untitled Film Still #33 (1979), by Cindy Sherman. This image is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Photo

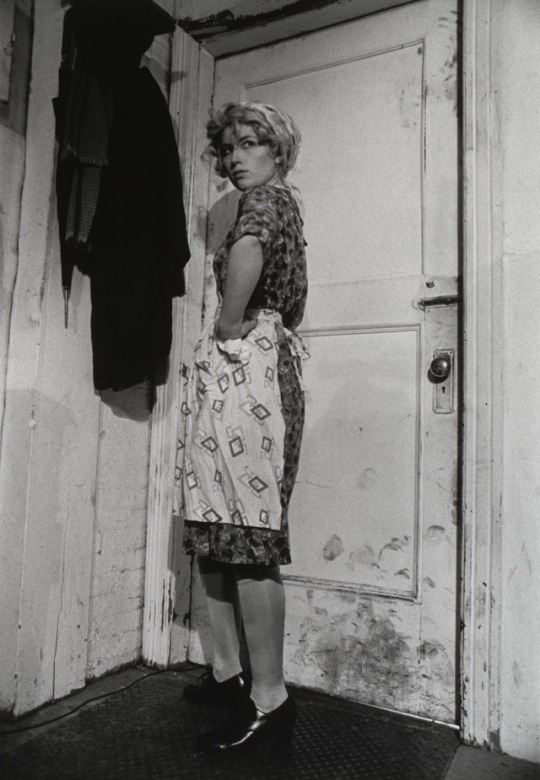

Untitled Film Still #63 (1980), by Cindy Sherman. This image is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Photo

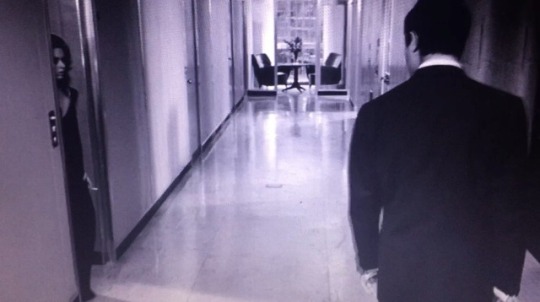

In the left (16:55) and right images (17:10), Giovanni is tempted by a young woman, presumably hospitalized to treat a psychological disorder (perhaps she is what was once called a “hysterical” woman). Compare her disheveled appearance and imploring manner with Untitled Film Still #28.

*The above images are taken from La Notte (1961), and are shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Photo

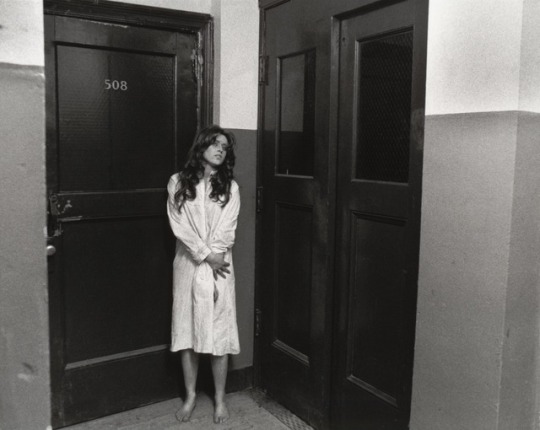

Untitled Film Still #28 (1979), by Cindy Sherman. This image is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Photo

Sophia Lauren plays Cesira, a mother witnessing the Allied invasion of Italy with her daughter during World War II, in Two Women (1960). Cindy Sherman names Lauren as a regular influence on her characters*. However downtrodden, Cesira is never broken, even when navigating between emotional independence and her affection for a persistent coal merchant (10:59). Compare Cesira’s tempestuous glare with Untitled Film Still #35.

*(p 8) Sherman, Cindy. The Complete Untitled Film Stills.

**The above image is taken from Two Women (1960), and is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes

Photo

Untitled Film Still #35 (1979), Cindy Sherman. This image is shared for educational purposes only.

0 notes