Audio

patriotism waves above our heads

overlooking swamps and shelters

rows of cars line the park’s edge

stop for intoxicated barbecues

around bonfires and gazouz

leaving back empty cans and bones

for stray dogs to chew

the ground sparkles green with celtia shards

crackles beneath the sneakers of few

in search of the city’s last patches of green

they find a lawless jungle amidst the grid

under a militarised gaze

full of plastic trees and cotton candy shrubs

the park, reduced to a transit zone

a zone of static drunkery

0 notes

Text

Manana - ‘a bridge between Santiago and the rest of the world’

1 Quote by Manana founder, Alain Garcia Artola.(https://video.vice.com/en_uk/video/celebrating-manana-in-the-city-of-music/579f5cb7c9f628430d9d030d)

Santiago de Cuba, 2016.

When speaking about electronic music, the notion of internet is almost implicit. It grants us access to the genre and is relied on by most musicians who release their work on platforms such as Soundcloud, Bandcamp and Spotify. The widespread nature of the internet has enabled independent artists all around the world to produce music and share it globally, all from their bedrooms. What however, would the reality look like for music producers who live in a country where only 5% of the population has access to internet services in their own homes? Where wi-fi can only be legally accessed at one of 237 hotspots throughout the country?

This reality is Cuba.

How might we envision an electronic music scene in such a locality? Regarding the lack of internet on the island, how do Cuban artists manage to tap into the international electronic music scene and get their voices heard? With these questions in mind, this paper explores the Manana project, a music label and Cuba’s first Afro-Cuban Electronic and Folkloric Festival, which ran from the 4th until the 6th of May in 2016 in Santiago de Cuba. The project strives to combat the lack of international exposure which Cuban musicians experience and explores the opportunities that these artists could benefit from through better connection with and integration in the international electronic music scene and industry. With this incentive, Manana records is producing and releasing albums which result from collaborative projects between some of the most exciting jazz, rumba and electronic music artists from Cuba and abroad. The creators of Manana strongly believe that the project can facilitate the creative development of both local musicians in Santiago de Cuba and international electronic music artists through the sharing of knowledge and technology. For this essay, I obtained most of my information through an interview which I conducted with Harry Follett, the founder of Manana, and Kadambari Chauhan who represents Manana records, in January 2018, and through various articles, press releases and promotional.

An off-line nation

Three major factors have been identified to have caused the absence of wide-spread internet connectivity on the island. Firstly, the US embargo has played a crucial role in determining which resources Cubans can or can not obtain, such as materials like optical fibre cables which are necessary to transmit internet communication signals (San Pedro 2016). Secondly, the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 lead up to the “special period”, a time of extreme economic depression in the 90s which resulted in an economic crisis, and during which the government found itself faced with more acute issues such as rescheming its agricultural and industrial sector. The government in power also feared that foreign investment, which could have facilitated wide-spread internet access, would weaken national sovereignty. Thirdly, after the Cuban revolution in 1959, the government recognised telecommunication methods as tools to undermine authority. The availability of internet was considered too big a risk to the stability of the government (Press 2011). The Cuban telecommunications service provider ETECSA offers cards which enable hourly wi-fi connectivity for about $2. These cards are extremely pricey, considering the weak internet strength that they provide and the average monthly salary in Cuba which is about $25 (Perry 2017). In Santiago de Cuba, wi-fi antennas have been set up in four main areas around public parks and a back alley. During the daytime, these areas are filled with people leaning against walls and sitting on the ground and park benches, gazing at their devices. (Hjorth 2017, 347)

Creating physical networks

Cubans have created alternative strategies to obtain data from the internet without actually going online, as well as setting up clandestine internet connections. “El Paquete Semanal” (“The Weekly Package”), is a usb stick or hard drive containing about a terabyte of files such as music, tv-shows, movies and apps, which “Paqueteros” (“media smugglers”) regularly update and distribute (Martínez 2017). Some government employees, doctors, professors, and students who get onsite internet access through their jobs or universities, sell their connections. One could also say that internet access is a form of remittance, with Cubans abroad sending sim-cards loaded with internet data to their families and friends back at home (San Pedro 2016). The lack of internet availability has also lead to the creation of an entire underground user network. Together, they’ve set up what is called intranet callejera (“the internet of the street”), “Snet” or “Streetnet”. This network hacks in to wi-fi antennas and broadband cables through black market computers which are spread across the island (Estes 2015). In an interview with Vice magazine, Cuban-based artist Isnay Rodriguez, also known as DJ Jigüe and the founder of the Hip Hop collective “Guampara Productions”, speaks about the importance of internet access for the careers of emerging artists. He can often be spotted, sitting on park benches with his laptop at 4 a.m., when the internet isn’t being used by as many people as during the day and runs significantly faster. To advertise gigs and events, artists and DJs spread the news through word of mouth, mass text messages and posters. The electronic music scene in Eastern Cuba have also set up their own network of “El Paquete Semanal” distributors, through which they circulate mp3 files of the newest electronic music (Scruggs 2016). Regarding the availability and popularity of “El Paquete” across the entire island, the medium could offer an incredible opportunity for underground electronic musicians to disseminate their work, however the most prevalent hard disks carry predominantly reggaetón mp3s, which is indisputably one of the most popular music genres amongst younger generations in Cuba (Mallonee 2017). More than popularise their own music and genre, “El Paquete” has helped in shaping and growing a community of electronic music lovers that are connected through a constant sharing of music. Instead of utilising the internet to discover new music, individuals connect and share files physically.

This notion of reciprocity also lies at the very heart of Manana, which in many ways has filled a gap between the local and international music scene, which could be considered a result of the lack of internet on the island, amongst other factors. The project was founded by Harry Follett, who is a London based consultant, Alain Garcia Artola, member of the hip hop group TNT la Rezistencia and artist from Santiago de Cuba, and Jenner del Vecchio, a digital producer currently based in Vancouver. ”Manana" is a word used by some Cubans to describe a spiritual connection between artists and their audience. According to Alain, Manana was originally the name of the wife of Máximo Gómez, a Dominican general who came to Cuba to fight in the war of independence. While the couple was separated, Manana would send her husband letters which were signed with, “with passion, Manana”. This name was picked up by early Rumberos who would use the it to articulate their emotions while playing, emphasising that when they played, they did it with as much passion as Manana felt when she wrote these letters to her husband. (As explained by Alain in “Where does the world 'Manana' come from?” (https://youtu.be/lUDsxTrElAQ)

Harry initially travelled to Cuba in 2014 with the intention of studying percussion with the batá master Mililian Galis in Santiago de Cuba, which is where he also met Alain. Santiago de Cuba boasts Afro-Cuban culture and is home to a large Jamaican and Haitian community, the latter descending from immigrants who fled Haiti in 1791 following the slave revolt. Music flows out of every corner of the city where son, trova, rumba and salsa concerts are hosted almost daily at state-run music halls such as the Casa de la Trova and Casa de la Tradiciones (Garber 2016). Harry and Alain immediately bonded and sought to set up an open door studio, where local musicians could drop in, record and experiment with electronic music. Only a small number of recording studios can be found in the city, such as the National Recording Studio (EGREM studio) and are not equipped with the hardware necessary to produce electronic music. In their makeshift studio, the two friends planned to record an album which would represent the contemporary musical landscape of Santiago de Cuba, which blends rumba, trova, son, bembé and other forms of Yoruba and Haitian music with contemporary influences and soundscapes. The format of an album proved to limit the musical potential and dynamics of the city, thus Manana was born. The two friends found themselves wondering, how the current music situation in Santiago de Cuba relates to international electronic music and artists and how a bridge can be built between them. It was the challenge of facilitating a fruitful collaboration through the sharing of knowledge and technology across genres and cultures which intrigued them most and which they were convinced could benefit all participants involved. The festival that came out of this collaborative project was one of the first major festivals in Cuba to have a focus on electronic music and feature international as well as local musicians. The political situation during this period was absolutely crucial to the festival’s successful execution. Barack Obama was the first US president to visit the island since 1928 and under his administration, travel restrictions related to the embargo between the US and Cuba, which was first imposed in 1958, were eased (Garber 2016).

Manana festival recognises and builds on the potential of electronic music and the international scene that is linked to it, to promote Santiago de Cuba’s local musicians and Afro-Cuban heritage.

The founders also believe that, “Cuba’s powerful blend of rhythm, flow and feeling will enrich the development of electronic music and its community.” (http://www.mananacuba.com/about-manana-cuba-2016/) Officially speaking, Manana isn't a festival, but a "cultural exchange" between foreign and Cuban musicians, which is managed by the Santiago Province Culture Office, “Cultura”. Alain, who is a popular rapper in Cuba and has good connections with the government, was able to pull some strings and win the project’s approval. The government’s institutions have almost complete control over cultural activities across the island and during the 10 months that lead up to the festival, the team had to maintain contact with them on a weekly basis and make sure they met the expectations of the Culture Office. It was also a challenge to convince the government to support a project which focusses on promoting Afro-Cuban religious music and rumba, as opposed to genres like son and salsa, which are commonly marketed as local music. Finally, it was the project’s approach of targeting an international audience and drawing publicity and tourists to the island which sealed the deal with the government in February 2015. By this point, Harry Follett had returned to London and recruited his friend Jenner Del Vecchio, who became the project’s third co-founder (Scruggs 2016).

The festival took place in May 2016 and was made possible through a successful crowdfunding campaign which was launched in October the previous year and helped the organisers raise about half of the costs necessary to execute the festival. There was a limited number of 500 tickets for international guests which could be purchased or obtained by donating to the crowdfunding campaign. For locals, tickets were adapted to the average monthly salary and priced at $4 (Scruggs 2016). Harry tells me that of all festival goers, about 70% were locals and 30% were international visitors. The Cuban government heavily subsidised the festival’s main location, the Teatro Heredia, and offered its state-employed musicians. Manana was run entirely through the help of passionate volunteers and received free logistic consultation and audio equipment from companies such as Elektron and Vermona and organisations like “No Nation”. After the festival, Manana donated much of this equipment to Egrem Studios and other privately owned studios in Santiago. Perhaps the most important part of the festival, were the workshops which took place before the festival and facilitated collaborative processes between international and local artists during which they could meet, jam and create music through an exchange of knowledge, talent and technology. The music that was produced during these sessions was performed during the festival. The festival itself stretched out across various venues in the city with parties taking place in courtyards, private homes and in the streets. Better known international artists included the British DJ/producer A Guy Called Gerald, Quantic, the Peruvian duo Dengue Dengue Dengue, and Nicolas Jaar, who all played the event in exchange for travel, room, and board.

Performing artists were evenly split between collaborators, DJs, and local Cuban musicians.The dynamic line-up offered the audience a chance to preview the experimental collaborative projects, discover the various styles of the Cuban musical landscape, or simply dance to their favorite local musicians.

Manana in the future

The Trump administration has tightly restricted travel to and business with Cuba, making the continuation of the festival extremely difficult. For now, the team is focussing on creating more collaborations within the country, recording and releasing new music and hopefully touring it abroad. One year after the festival, the Barbican hosted Manana for “a night of Afro-Cuban Collaborations”, which brought some of the festival’s best collaborative projects to London. The show featured Obbatuké who were grouped with the electronic music duos Soundspecies and Plaid, Ariwo, and DJ Tennis who performed with Tito (Obbatuké) and Alayo (Alain’s pseudonym).

Manana has proved to be a sustainable project by maintaining its long term collaborations as well as facilitating new ones. Its record label has released three of these collaborations as albums through the label !K7. Among these productions are “Obbatuké”, a five track album by the like-named rumba group, an album by “Ariwo” which is a Cuban/Iranian collective that brings together Pouya Ehsai, Hammadi Valdes, Yelfris Valdes and Oreste Noda, and a collaboration between the UK’s Soundspecies and Ache Meyi which blends Afro-Haitian rhythms like bembé with electronic dance music. The project has found ways for Cuban artists to circumvent the lack of internet and still gain international exposure and recognition. It has also allowed these artists to explore technological possibilities to further develop their music by linking them with the electronic music scene. It goes without saying that international electronic musicians can gain much through such collaborative projects, both creatively as well as financially. What is important for the future of this project is that it maintains its strict reciprocal nature and continues to respect and guarantee the creative ownership of the actors involved.

Hector from Ache Meyi, Santiago de Cuba 2016.

Henry and Oliver Keen from Soundspecies, Santiago de Cuba 2016

References

Estes, Adam Clarke. “Cuba’s Illegal Underground Internet Is Thriving,” January 26, 2015. https://gizmodo.com/cubas-illegal-underground-internet-is-thriving-1681797114.

Garber, David. “Wi-Fi Cards, DIY Parties, and Food Rations: I Went to Cuba’s First Major Electronic Music Festival.” Thump, May 17, 2016. https://thump.vice.com/en_au/article/kb53yz/wi-fi-cards-diy-parties-and-food-rations-i-went-to-cuba39s-first-major-electronic-music-festival-au-translation.

García Martínez, Antonio. “Inside Cuba’s DIY Internet Revolution | WIRED,” July 26, 2017. https://www.wired.com/2017/07/inside-cubas-diy-internet-revolution/.

Greg, Scruggs. “Why This Festival Could Spark Cuba’s Electronic Music Revolution - Thump,” May 5, 2016. https://thump.vice.com/en_us/article/ae87qb/cuba-electronic-music-festival-manana.

Hawthorn, Carlos. “A Guy Called Gerald, Gifted & Blessed Head to Cuba for Manana.” Resident Advisor, February 8, 2016. https://www.residentadvisor.net/news.aspx?id=33303.

Hjorth, Larissa, Lecturer in Digital Art in the Games Program Larissa Hjorth, Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell. The Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography. Taylor & Francis, 2017.

Lula, Chloé. “The Festivals Fighting To Preserve Latin American Music.” Telekom Electronic Beats (blog), February 27, 2017. http://www.electronicbeats.net/conversation-comunite-manana/.

Mallonee, Laura. “How Reggaetón Exploded All Over Cuba Without the Internet | WIRED,” 2017. https://www.wired.com/2017/03/lisette-poole-reggaeton/.

Pedro, Emilio San. “Internet Access Still Restricted in Cuba.” BBC News, March 21, 2016, sec. Latin America & Caribbean. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-35865283.

Perry, Kevin EG. “Manana: The Festival Helping Contemporary Cuban Music Go Global.” the Guardian, May 19, 2017. http://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/may/19/manana-festival-helping-cubans-forge-dance-music-connections.

Press, Larry. “The state of the Internet in Cuba.” The Internet In Cuba (blog), January 2011. som.csudh.edu/cis/lpress/cuba/chapters/lpdraft2.docx.

Scruggs, Greg. “How Do Cubans Make Electronic Music Without Reliable Internet?” Thump, July 26, 2016. https://thump.vice.com/en_us/article/yp45w7/cuba-electronic-music-technology-internet.

Photographs

All images were used with the permission of the photographer, Theodore Clarke. http://www.the0dore.com/

1 note

·

View note

Text

How does the concept of every day bordering enhance our understanding of migrants’ experiences: A look at the UK’s housing and employment sector

Introduction

Early exposure to borders can be traced back to childhood, such as the experience of growing up in a nuclear family. Who is part of the family and who isn’t? Who belongs within the home and who doesn’t? The walls of a home can be seen to represent borders that distinguish a space of order, which is governed by rules, from a space that is considered a realm of chaos. In this sense, the home can be regarded as a safe haven where people are united by a common sense of belonging (Tétreault et al. 2009, P. 112). How can we understand borders when their geographic reach is extended to the nationstate? How do inhabitants of this space adapt to a larger demographic and geographic scale in an attempt to find belonging and safety? In what way does the state intervene to maintain this sense of order and is its notion of order compatible with the people’s understanding of it?

Theoretical Framework

Since the implementation of the 2014 Immigration Act in the UK, legislative authorities have put the general public under increasing pressure to act as its border patrols.

In response to this circumstance, the research project “EU Borderscapes” was formed, to study borders “in relation to fundamental social, economic and geopolitical transformations that have taken place in the past decades” (www.euborderscapes.eu). Led by scholars such as Nira Yuval-Davis, who is in charge of the research group based at East London University, the project is producing invaluable data which helps to illustrate the implications of everyday bordering for public services and its effects on the experiences of migrants and civil society in general. EU Borderscapes defines everyday bordering as “the everyday construction of borders through ideology, cultural mediation, discourses, political institutions, attitudes and everyday forms of transnationalism” (Georgie Wemyss) and integrates the term ‘b/ordering’ which was coined by Van Houtum et al. through the book “B/ordering Space” and implies an intersection between borders and social ordering (Yuval-Davis, 2017). Through an intersectional framework, the project scrutinizes practices which attempt to enforce order through the embodiment of borders in everyday life, and argues that social relations are being significantly challenged while monitoring and patrolling tasks are being outsourced from external borders and guards, to civil society.

In “Global Politics as If People Mattered”, Tétreault et al. distinguish between social borders, which are characterised by ethnicity, religion, class, language, etc. and borders that separate nation states, which are considered products of imperialism and have little relation to people’s social borders but rather to the economic interests of colonial powers. In this light, borders are regarded as methods for the powerful to remain in control over the less powerful and find their way in to every dimension of human social organisation. Borders however are not impermeable and therefor subject to change. While the powerful seek to maintain them, the less powerful attempt to transcend them (Tétreault et al. 2009, P. 111). It is arguable that the more migrants trespass borders, the more autochthonous inhabitants fear for their access to public services. The stigmatisation of migrants through vilifying media representation, only serves those in power to reinforce borders on an external and local level, by emphasising immigration’s threat on employment, welfare, the economy and safety, hence legitimising the enforcement of more austere and hostile policies which will secure their own long-established hierarchies. (Tétreault et al. 2009, P. 109). With this framework in mind, I argue that an intensive examination of the housing sector, and its methods of inclusion and exclusion through bordering practices, is crucial to enhance our understanding of the hardships which migrants face in the UK, especially asylum seekers and recent arrivals (5 years or less).

Borders in Britain’s housing sector

What is more crucial to a recent arrival than access to shelter? While some must initially reside in hostels, they are soon handed over to private firms such as Serco and G4S that mainly offer ��hard to let” accommodation. Recent arrivals are ineligible for council housing and often do not have the freedom to choose where they would like to live upon arrival in the UK, due to dispersal policies and financial barriers. Adequate housing is not solely a physical need, but functions as a base to create or rebuild social networks. This is especially crucial for refugees and asylum seekers which lack welfare benefits and whose livelihoods depend of the support of their communities (Allsopp et al. 2014, P. 27). Furthermore, the UK government has recognised housing as a key factor of refugee integration (Home Office 2005). It is safe to say, that housing conditions play an important role on shaping experiences of refugees while they determine a person’s sense of safety and belonging in a certain space, and impact that person’s access to healthcare, education and employment (Herrick 2005, P.3).

Public debate has notoriously linked the shortage of social housing to increasing immigration. This discussion was especially stimulated by Ex-Cabinet Minister Margaret Hodge who argued that established families should be prioritised over new economic migrants in the allocation of social housing (Hodge 2007). Right-wing think-tanks such as “Migrationwatch” regularly publish reports expressing “concern about the present scale of immigration into the UK”. In 2006, they concluded that “high levels of international migration have been a major factor in the housing shortage and have contributed to the rise in house prices which, in turn, has led to serious problems of affordability” (Migration Watch UK 2017). A glimpse into one of these briefing papers is enough to understand that the nucleus of their concern is the prosperity of the white English working class family, as they pay little to no attention on the hardship that migrants face in the wake of the “housing crisis”. Reports as such have lead to the common misconception that the lack of housing and the rising real estate prices, are caused primarily through an inflation of international immigration. This argument is flawed as it ignores factors such as the privatisation of property by buy-to-let landlords and property investors.

Additionally, it holds migrants responsible for overall population growth and fails to address circular migration or temporary settlement patterns of migrants. Their solution to the housing deficit is to curb immigration, “more homes need to be built in England but a key component of solving the housing crisis must be a reduction in immigration to reduce demand” (Migration Watch UK 2017). Such statements have done much damage by feeding into the general public’s understanding of migrants as unwelcome and undeserving subjects.

Before the turn of the 20th century, borders were pretty flexible and porous, with border crossings an everyday reality, especially for people living and working in rural areas. It was only during World War I that passport checks were enforced by European governments as a security measure, and to facilitate the emigration of people who were considered to have “useful” skills (Tétreault et al. 2009, P. 104). On that note, the primary function of borders is to guarantee the economic prosperity of a designated group, rather than to protect their national identity. These means of control have stayed in place ever since and have become absorbed as natural divisions. Yuval-Davis traces the inwards extension of the UK’s border back to the privatisation and deregulation of state roles and the welfare system succeeding World War II (Yuval-Davis P-6). Corporate investment in the private rental sector has led to the inflation of real estate value, the de-regulation of rent and an ever increasing shortage of social housing. The sector is under extreme pressure due to its flexibility, in contrast to social housing and owner-occupancy, as it not only accommodates a vast spectrum of households, but also must ensure that social housing demands remain low. According to the Migration Observatory, foreign-born people are almost three times more likely (41% in 2017) to be in the private rental sector than UK-born people (15%). At the same time, recent arrivals are almost twice as likely to be renters in the private sector (80% in the second quarter of 2017), compared to migrants in general (The Migrants Observatory 2017). It has been argued that an increase in immigration affects the price of housing. In regards to social housing, this is a misleading assumption as prices are capped, the availability on the other hand, can be impacted. We can presume however that an increase of migrants leads to an increase in demand for rented accommodation, encouraging investors to enter the buy-to-let market, contributing to the further privatisation of the sector. In the case of recent arrivals and asylum seekers, this could also swell the availability of “hard-to-let” properties on the market, which might suggest a general reduction in the average price of houses and quality of life in the area (Yuval-Davis 2016).

The definition of homelessness experienced a big shift in 1993 when the Asylum and Immigration Appeals Act was implemented. Before this, asylum seekers were treated no different than the UK born population when applying for homelessness services. According to the law, whoever had lost the right to remain in their home or was forced to move because of ill-suited living conditions, was considered “homeless”. The 1993 Act deemed asylum seekers ineligible for homeless services if accommodation was “available to them”, regardless of the property’s state. The act also forced asylum seekers to take up temporary housing until their asylum case was settled, as opposed to “regular” homeless people, who were put up in permanent housing. Through the 1996 Asylum and Immigration Act, asylum seekers were denied the right to social housing and their access to public services was severely restricted (Guentner et al. 2016, P. 14-15). These policies illustrate the neoliberalisation of one of the most basic public services and human rights, which is the right to adequate housing. The increasingly privatised housing sector capitalises on those who have no choice but to fall back on the private sector, as their immigration status prevents them from accessing social housing and owning property.

In 2013, the government commanded local councils to favor social housing applicants who could prove a proximate link to their immediate environment and enforced requirements for residents to demonstrate 2 years of residency in the area before becoming entitled to social housing. Some councils now ask for applicants to prove 5 years of residency and some have proposed to raise the requirement to 10 years

(Guentner et al. 2016, P.15). The 2014 Immigration Act saw an extension of borders from the social housing sector to the private sector. The act determines a migrant’s “right to rent” in relation to their immigration status: indefinite for those with indefinite leave to remain, limited for migrants with limited leave to remain, and completely refused to those with no leave to remain. Through these new conditions, land-lords/ladies are demanded to behave as border guards and must force all tenants to produce the required documents in order to access accommodation, and face imprisonment if they fail to do so (Guentner et al. 2016, P.14-16). This condition applies to all tenants residing in the property, not only to those who are named on the lease. One could argue that this might lead to an increase in arbitrary raids of households which are suspected of hosting “irregular” migrants.

When speaking of housing, it is also important to examine dispersal policies and how they can influence tendencies of everyday bordering as well as how they work to exacerbate or reduce poverty among refugees and asylum seekers. I argue that the uneven dispersal of migrants exacerbates poverty by separating asylum seekers from existing social networks and instead settles them in areas where there may be a lack of infrastructure that can meet the demands of their daily needs, such as translators or communities who speak the same language and can assist them in accessing public services. Especially dispersal areas which are characterised by pre-existing social deprivation, division and high unemployment may meet asylum seekers with hostility and racism (Herrick 2005, P. 13).

Borders, employment and the politics of autochthony

These austere policies also apply to the employment sector, where according to the 2016 Immigration Act, employers can be imprisoned for up to 5 years if they fail to prove the required documentats for their staff on multiple occasions or be fined up to 20,000 pounds per undocumented employee. This act also transfers rights to immigration officials, allowing them to raid and seize businesses which they suspect of facilitating illegal work. Those who suffer the effects of the bill most are in many cases migrant business owners who often struggle to keep up with constant immigration controls and lack the training or experience to distinguishing “legal” from “illegal” employees (Yuval-Davis 2017, P. 7-8). This act plays an important role in reinforcing non-physical borders, as it encourages a notion of suspicion amongst lessors and employers towards anyone who looks the slightest bit “foreign” (Grant, 2015). This could lead to the increasing tendency of favoring white tenants or employees who, based on their skin color, pass as “legal”, hence perpetuating the stigma of people of color and migrants as “law-breakers”. This leaves little to no flexibility for people of color who may possess all required documents but are excluded from opportunities of housing and employment simply because lessors or employers don’t want to risk issues with legal authorities (Sue Lukes, “Everyday Bordering”). These racial bordering practices trickle in to our every day lives and can significantly reduce social solidarity within communities, enforcing the idea that some classes or ethnic groups are more “deserving” than others. Yuval-Davis draws on Geschiere’s interpretation of “autochtony” in regards to everyday bordering practices as it provides a more flexible framework to discuss notions of belonging. According to Geschiere, “autochtony” can be claimed by a group which state they “were here before”, allowing a malleable status of “native” according to the needs of an autochtone political agenda. This helps to sustain the belief among the “deserving and autochtone” population, that migrants deserve social disadvantage as they merely drain public services intended to serve “locals” (Geschiere 2009). When migrants are excluded from claiming public services, they are forced to turn to “unofficial” service providers. In the case of housing and employment, migrants must settle for poor living and working conditions, which lack regulation and hence increase their probability of exploitation. This results in the nourishing of a social class, which comprises bodies that are exempt from legal protection and that are forced to live in unhealthy and dangerous living conditions while engaging in precarious work. The provisions of the 2014 Immigration Act have given the illegitimate and exploitative housing sector a much welcomed boost, as migrants are becoming increasingly criminalised and corrupt lessors are decriminalised (Sue Lukes, “Everyday Bordering”). It is safe to say that the politics of autochthony, which constantly reevaluates notions of belonging according to political agendas, compels those deemed as autochthonous, to implement bordering practices in their everyday lives. I argue that this severely impeaches the civil liberties of both the “guards” as well as the “trespassers”. Not only does this undermine the dignity and safety of those regarded as “foreign”, but also exploits the “autochthonous” by transferring them responsibilities and tasks of immigration services. Consider military forces as an example, who are given professional training to execute their border-guard duties and are criminalised only if it is proved that they disobey their duties intentionally. Internal border-guards, in our case lessors and employers, who fail to carry out their duties, are harshly criminalised and prosecuted, regardless of their lack of training or interest to cooperate (Yuval-Davis 2016).

Furthermore, one could say that everyday bordering practices stem from an intention to govern bodies in order to create a “hostile environment” (Yuval-Davis 2017, P. 6).

By denying migrants basic rights such as the right to employment, housing, education and health care, life in the UK is made unsustainable for “undesired” migrants. Even the basic right to mobility is unattainable for many, as the 2014 Immigration Act criminalizes undocumented people for driving in the UK, and especially in the case of London, financial barriers block people on low incomes from accessing the public transportation network. Internal bordering is a more deceitful means of exclusion than external bordering, as it creeps in to the everyday life of society. It can be considered unpaid work which is carried out, in many cases, unconsciously by under-qualified people who embody a political agenda which’s goal is to commodify welfare by introducing a class-based project. The aim of this project is on the one hand to strip migrants from welfare provision, and on the other hand to reserve welfare provisions for those who fit the right status of belonging, according to categories such as citizenship and social class (Guentner 2016, P. 406). Borders are welcome where fear and threat are abundant, therefore vilifying migrants and associating them with welfare drainage, terrorism, and crime, facilitates the erection of non-physical borders between autochthonous inhabitants and migrants.

Countering everyday bordering

The increase of land privatisation and neoliberalisation of the real estate sector has proved to create great challenges for lower to middle income people, especially working class migrants. Increasing rents are pushing them out of their estates and neighborhoods and forcing them to close or relocate their businesses. In this section I would like to briefly look at one example of how migrants have adapted to these changing conditions by autonomously altering their housing situations and business models.

Commercial tenants: the story of Rye Lane

Peckham has been at the heart of urban and social redevelopment during recent years and the growth of land value has resulted in the limitation of resources for lower income people. Two thirds of Rye Lane’s businesses are owned by migrants, hailing from over 20 different countries. How do these business owners adapt to rising real estate prices?

In order to survive under these circumstances, business plans must be flexible. Some start out on a small scale, selling products from stalls, with options to extend to a shop unit in the case of commercial success. Unaffordable real estate has lead to what the urban Ethnographer Suzanne Hall calls “urban mutualism”, which implies that different sections of one property are sublet to different retailers, who split the rent between each other. One shop may have a magazine vendor outside, a mobile phone vendor taking up a small counter by the door, a cloth store against one wall, and a barber shop against the other (Misra 2015).

Conclusion

Everyday bordering, which is enforced and normalised through legislations such as the Immigration Acts and Bills, subvert our human rights, and in the specific context of London, behave as a threat to ethnic, religious and racial coexistence within the city, which is arguably its most noteworthy characteristic (Yuval-Davis 2017, P. 12).

Additionally, I argue that everyday bordering is part of a neoliberal political agenda to divert the public’s attention from large scale displacements through regeneration schemes and the privatization and marketization of public services and social housing, to the issue of migration as the leading factor of the UK’s housing crisis. As civil society, we must counter these imposed practices and prevent them from influencing our everyday lives. We are otherwise offering our bodies as simple vessels to neoliberal political agendas which promote the oppression of the poor (Yuval-Davis 2016). Academic work on the precarious living and working conditions of migrants, and especially asylum seekers in the UK, must be made accessible to the wider public in order to counter hostile reporting on migrants as “burdens” to the state in mainstream media. Collective awareness is absolutely vital to strengthen a solidarity movement which will help us resist the state’s imposition to act as its border guards and instead oppose it in defense of those who are forced to live in and work under inhumane conditions.

References

Allsopp, Jennifer, Nando Sigona, and Jenny Phillimore. 2014. “Poverty among Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK”. IRIS WORKING PAPER SERIES, NO. 1. Institute for Research into Superdiversity, University of Birmingham

Centre for Research on Migration Refugees and Belonging. 2015. “Everyday Borders” (video). Accessed March 26, 2018. University of East London.

https://vimeo.com/126315982

Geschiere, Peter. 2009. “The Perils of Belonging: Autochthony, Citizenship, and Exclusion in Africa and Europe”. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

Grant, Saira. 2015. “Right to Rent Checks Result In Discrimination Against Those Who Appear ‘Foreign’.” Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants. Accessed March 26, 2018. http://www.jcwi.org.uk/blog/2015/09/03/right-rent-checks-result-discrimination-against-those-who-appear-%E2%80%98foreign%E2%80%99

Green, Lord Andrew. 2017. “Immigration and Housing.” Migration Watch UK. Accessed March 26, 2018. http://www.migrationwatchuk.com/briefing-paper/document/438

Guentner, Simon, Sue Lukes, Richard Stanton, Bastian A. Vollmer, and Jo Wilding. 2016. “Bordering Practices in the UK Welfare System.” Critical Social Policy 36 (3): 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018315622609

Herrick, Christine. 2005. “Integration Matters – A National Strategy for Refugee Integration.” Race Equality Teaching 23 (3): 36–40. https://doi.org/10.18546/RET.23.3.09

Hodge, Margaret. 2007. “Margaret Hodge: A Message to My Fellow Immigrants.” The Guardian. Accessed March 26, 2018. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2007/may/20/comment.politics

Migration Observatory. 2017. “Migrants and Housing in the UK: Experiences and Impacts.” Accessed March 26, 2018. http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migrants-and-housing-in-the-uk-experiences-and-impacts/

Misra, Tanvi. 2015. “The Innovative Way Immigrant Businesses on This London Street Adapt to Gentrification.” CityLab. Accessed March 26, 2018. http://www.citylab.com/work/2015/10/how-immigrant-businesses-on-one-london-street-adapt-to-rising-rents/407977/

Tétreault, Mary Ann, and Ronnie D. Lipschutz. 2009. Global Politics as If People Mattered. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Yuval-Davis, Nira, Georgie Wemyss, and Kathryn Cassidy. 2017. “Everyday Bordering, Belonging and the Reorientation of British Immigration Legislation.” Sociology

Vol 52, Issue 2, pp. 228 - 244

Yuval-Davis, Nira, Georgie Wemyss, and Kathryn Cassidy. February 17, 2016. “Changing the Racialized ‘Common Sense’ of Everyday Bordering.” OpenDemocracy. Accessed March 26, 2018. https://www.opendemocracy.net/uk/nira-yuval-davis-georgie-wemyss-kathryn-cassidy/changing-racialized-common-sense-of-everyday-bord

0 notes

Text

Contested soundscapes of urban informality: Soho’s rickshaw drivers

Authoritarian structures of governing work hard to challenge the existence of informal activities in the public realm. Creative or personal construction of public space is quickly met with suspicion, and in some cases even persecution and arrest, as “irregular” activities are often considered nuisances or associated with idleness, homelessness and crime. Our understanding of public spaces in cities seems to be shrinking in flexibility as our common perception of streets’ functions is often limited to that of transit.

Through this research project, I aim to explore the informal nature of pedicabs in London and attempt to identify issues that people face who work in this sector. In particular, I will be focussing on music’s role in both ameliorating their working conditions as well as oppressing their profession.

“Pedicabs”, or “rickshaws”, are three-wheeled bicycle taxis which operate through a legal loophole that emerged through the Metropolitan Public Carriage Act from 1869. This act classifies pedicabs as stage carriages and authorises them to ply for hire, as long as they run without motors. Spokespeople from TfL have claimed that they collaborate with the police “to deal with unsafe and antisocial pedicabs on the Capital's streets. Pedicabs are the only form of public transport in London that is unregulated and our powers are extremely limited, but we are doing all we can to enforce against dangerous and nuisance riders” (Rea 2017). According to the London Pedicab Operators Association, a voluntary association which represents the interests of the pedicab industry in London and has brought forth a code of practice for the profession, TfL refuse to engage in negotiations with them about the regulation of pedicabs (Chester 2015). The council of Westminster has enforced a legislation which forbids pedicabs to play music after 9PM, a law which has, according to testimonies from pedicab drivers, been exploited by the police to arrest undocumented workers and seize their pedicabs. They also claim that it encourages pedestrians and locals to file noise complaints in an attempt to further stigmatise the profession. Statements such as, “pedicabs are responsible for congestion issues, the overcharging of tourists and threatening of their safety” are common in British mainstream media (Hellier 2016). In December 2012, Boris Johnson attempted to ban pedicabs, insisting that "although there are a number of responsible pedicab companies, the fact is that these vehicles jam up the capital's roads and consistently fail to ensure the safety of their passengers” (TfL 2012). The common assertion that they contribute to congestion should be scrutinised as it overlooks the city’s flawed transport infrastructure which can be dangerous for both cyclists and pedestrians. Rickshaws however, could decrease congestion and pollution in London, which in January 2018 already reached its annual limit (Gabbatiss 2018). Pedicab drivers believe it is their right to play music at a moderate volume during working hours, as it uplifts their own and customer’s spirits. This targeting of defenseless and informal actors, by condemning them as “nuisances”, has proved to function as a method of ridding the streets of all unregulated activities and distract from more crucial issues that arise through economic development in urban hubs which would require systemic change to be improved (Wagner 2018).

Industrial production has created considerable constraints on our capacity to perceive public space from a variety of perspectives to a perspective of a space which is “organized for and by consumption” (Lefebvre 2003, P.20). I find a great deal of parallels between my observations of Soho’s streets and Henri Lefebvre’s understanding of the street in “The Urban Revolution”, which seeks out to uncover the street’s potential of facilitating social encounters. With the invasion of the automobile, social interaction in the streets is disappearing as urban life becomes increasingly functionalised, while its ludic and informative functions are overlooked. He also discusses the notion of movement within cities, which can both be forced and repressed by authorities who attempt to restrict the lingering and assembling of bodies, conditioning us to suspect people who use the public space for social or economic recreation and regard them as irregular (P.21).

Public space is defined by a sense of formality and public etiquette, which I consider a form of regulation and control over our individuality and creativity. Pedicabs don’t seem to fit this idea “formality” and are therefore confronted with hostility from political authorities who fear to lack power over their control. My research has lead me to believe that by playing music, pedicabs can transform our perception of public space in the urban environment, in particular streets, and create possibilities for social encounters and the exchange of knowledge. Through sharing my observations, I hope to illustrate that Soho’s streets can be regarded as an interactive theater where agents’ roles are liminal and shift between performers and spectators. Furthermore, I strive to shed light on the way that music is being instrumentalised by policy makers to target pedicab drivers and threaten their livelihoods. Instead I propose an alternative method of inquiry, in this case through dialogue about music, to identify the profession’s issues and struggles, in the hopes that government bodies such as TfL find ways of cooperating with pedicab associations and support them in developing a regulation system which will improve the precarious situation of the sector.

Monday, 9. April

Our story begins on Old Compton Street, just outside of Prince Edward Theater, where a row of pedicabs are parked. It’s about 10PM on a very wet and cold day in April, and it’s the rickshaw drivers’ last shot at finding customers before business officially dies off for the day. Amongst the noise of passing people and cars, blaring music of clubs and bars, one can hear the occasional bike horn honk and phrases such as “hello Miss, rickshaw ride?” and “London is more beautiful from the back of a pedicab”. One pedicab plays Haddaway’s “What is Love” from a soundsystem and introduces himself as Milan. “I usually play classical music”, he says. Milan has travelled all around Europe and came to the UK almost 10 years ago to do his masters. He goes on to tell me about how slow his day was and that he’s only made 12 pounds so far. He says, “only Brits today. They’re the worst customers.” Their lack of trust in pedicabs mainly stems from a video which was published online a couple of years ago and shows a pedicab driver charging a tourist 600 pounds for a short ride. Milan says he can easily charge a couple hundred pounds for a half-hour ride from rich people who don’t know any better. I ask him if he thinks he attracts more customers through his music and he says, “of course, and through my decoration!”. His sound system is attached to the frame of his bike around which he has hung fake plants and attached a disco light which flashes in different colors. His carriage is decorated with more fake plants and stickers, one of a Qatari football team, he tells me “to attract rich Qatari customers”, and two stuffed pikachus which he places on the bike’s backseat.

By now, all of the other pedicabs have left to try their luck at Queens Theater down the road. Milan tells me to meet him there later. On my way to Queens Theater, I cross paths with Soho’s night crowd, promoters trying to lure people into clubs, tourists heading home from China Town, homeless people trying to knick a pound or cigarette from partygoers. Once I reach the theater, I hear a horn honk and turn around to find Milan on his bike. He immediately continues his storytelling. “Pedicabs are a tricky business”, he says, “most of us are documented but some aren’t, and it’s the undocumented workers who come out late at night to avoid the police and offer rides at unbeatable prices, stealing our customers”. “There are other ways however, to earn an extra dime or two”, he tells me that he gets commissions from brothels to bring people there. “I can also help customers get other things, if you know what I mean”, he tells me. I ask Milan if he would prefer his profession to be regulated? He says, “are you kidding me? No way!”. Regardless of the prejudice and legal issues around pedicabs, he prefers the sector to remain irregular as it allows him to make more money. Pedicab drivers who rent their cycles and work for authorised companies, such as Bugbugs and London Pedicabs, charge a regulated fee and are in favor of the sectors’s regulation which could protect them from stigma and discrimination which they owe to the few pedicab drivers who bend the rules. We’re joined by another pedicab driver who parks beside us. Milan begins to swear at him for hanging a price list onto his bike. Milan says, “that’s illegal”. I ask him, “what is”? “The pricelist!”. I wonder, “how can something be illegal when the profession itself isn’t entirely regulated?”. Milan says, “it simply is.” I wonder if, within this informal system, Milan has created his own set of rules which determine what is legal and illegal. It’s about midnight now and the streets are emptying. We say goodbye and Milan invites me to meet him tomorrow at the Comedy Store down the road on Oxendon Street where he’ll be watching the football match.

Thursday, 12 April

It’s another damp and chilly night in Soho when I meet Volkan from Turkey in front of Palace Theater. He’s listening to “Sweet Dreams” by the Eurythmics so I ask him if he always plays music at work. He tells me that it’s his favorite part of the job. It gives him joy and motivation and sometimes helps him connect with clients as he lets them play their favorite tracks through an aux cable. In his view, a pedicab ride is a way to experience and discover the city rather than a mode of transport. Just a couple of days earlier, the media had reported about a pedicab driver who tried to charge two tourists 150£ for a short trip from Selfridges to Knightsbridge. Volkan says that after each such incident he can feel the negative effect on his reputation. Two tourists interrupt our conversation and ask for a ride to Green Park. The minute Volkan drives off, I hear a bike horn and blasting classical music. “Hey you! This is from your country! Your national heritage!”. Milan’s back with “Dein Ist Mein Ganzes Herz” by Franz Lehár. I’ve never heard the song before and he tells me that I can’t possibly be Austrian if I don’t. He’s in a hurry to get somewhere and tells me to find him in Chinatown in half an hour. Parked next to the theater, I find Zaman from Bangladesh. He’s got a beautifully decorated bike and a big set of speakers. I ask why they’re turned off and he tells me, “it’s past 9PM! If the police catch me, I can get a huge fine or my cab could get seized!”. Soho feels like one of the loudest spots in central London, where drunk people shout and stumble across the streets and music blares out of nightclubs. The sounds of motored vehicles pollute Soho’s soundscape but still pedicabs are targeted and prohibited to play music during their busiest working hours. Zaman obeys the law out of respect for the residents who wake up early to go to school and work. He comments on passing pedicabs that play loud music and worries that they’ll jeopardize his reputation. I ask him if he thinks that the council enforced this legislation to legitimise the arrest of pedicabbers which they suspect to be undocumented workers. Zaman tells me it’s possible, but he blames pedicabbers themselves for not caring enough to enquire about the law and avoid problems. I thank Zaman for chatting to me and decide to head down to Wardour St. to see if I can find Milan. I find him parked in the middle of the pedestrian zone, waiting for work along with four other pedicab drivers. Milan immediately clarifies that he’s not really friends with the other pedicabbers. “It’s not me, it’s them! I don’t know why but they think I earn more money than they do!”. I ask him, “why?”. “What can I say? I’m a business man!”. Milan has a special way of dealing with clients which I get to experience in full action. A very drunk man approaches him and babbles, in words which I can’t quite make out, that he wants to go somewhere to get something. Milan tells him that he can get whatever he’s looking for in Camden and that he can take him there and back for 20 pounds. The drunk man agrees and calls for his friend. Milan tells me to wait for him and that he’ll be back in 20 minutes. I try to comprehend how Milan will manage his trip in 20 minutes but agree to wait for him. Meanwhile I speak to Pressi, another pedicab driver, who’s parked on Wardour St. and drives the slickest rickshaw in town which he’s named “Impressia”. I have heard other pedicabbers speak about him, calling him “the guy with the nicest bike in West End” or

“the man with the best soundsystem in town”. He starts telling me about “Impressia", which has its own website and which he built from scratch in Bulgaria. He then shipped it to Finland where he worked and lived for a couple of years before coming to London.

He continues to tell me about his passion for the movie “Into the Wild” and how one of the movie’s quotes, “Happiness is only real when shared”, inspired him to start a Facebook platform through which people from Bulgaria could connect. He tells me that, besides his bike, the platform is his proudest achievement in life and has helped people to meet, marry and start families. Milan’s back with a honk and Pressi ignores him. He tells me that Milan is jealous that we are speaking and jokes that I should ask him to be my boyfriend because he has 500.000€ in the bank. Milan keeps honking and puts on “Dein Ist Mein Ganzes Herz” again. I say “bye” to Pressi and join Milan. He tells me that he took the two drunk men up the road to some drug dealers, fooled them into thinking they were in Camden and brought them back after charging them 20 pounds. He then says, “man’s gotta make a living!”. Exploitations like these have come to shape the general perception of pedicabs in London. From all of the rickshaw drivers I spoke to, Milan’s behavior struck me as unique. Everyone else seemed to really fear for their reputation and livelihood and make an effort to work transparently, with an overall aim for the sector to become regulated and their jobs to be secured.

Some names in this paper have been modified to protect the identities of the pedicab drivers.

A soundmap of pedicabs in Soho, London

www.soundcloud.com/3am3ali/contested-soundscapes-of-urban-informality-a-soundmap-of-pedicabs-in-soho-london

References

Chester, Tim. Rickshaw Wars: Behind the handlebars of London's secretive industry. Mashable. 13 August 2015. Accessed April 26, 2018.

https://mashable.com/2015/08/13/rickshaw-wars-london-pedicab-industry/

Gabbatiss, Josh. One of London's busiest roads hits annual pollution limit with 335 days left of 2018. The Independent. 30 January 2018. Accessed April 25, 2018.

https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/london-busiest-roads-annual-pollution-limit-brixton-passed-2018-car-fumes-vehicles-uk-a8185416.html

Hellier, David. Transport for London Moves to Clamp down on Rickshaw Riders. The Guardian. The Guardian. January 1, 2016. Accessed April 25, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jan/22/transport-for-london-rickshaw-riders-uber

Lefebvre, H., & Bononno, R., 2003. The urban revolution. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Rea, Samantha. London’s Pedal-Powered Rickshaws: Scourge Of Soho Or Eco-Friendly Fun? Londonist. 6 November 2017. Accessed April 25, 2018. https://londonist.com/london/features/london-s-pedal-powered-rickshaws-are-they-the-scourge-of-soho-or-eco-friendly-fun

Roy, Ananya, and Nezar AlSayyad. Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives From the Middle East, Latin America and South Asia. Lanham, Md. ; Oxford: Lexington Books, 2004.

Transport for London. “Mayor Seeks Ban on Dangerous Pedicabs.” Transport for London. December 14 2012. Accessed April 25, 2018. https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2012/december/mayor-seeks-ban-on-dangerous-pedicabs.

Wagner, Kate. City Noise Might Be Making You Sick. The Atlantic. February 20, 2018. Accessed April 25, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/02/city-noise-might-be-making-you-sick/553385/

Wikipedia contributors. Soho. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Accessed April 25, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Soho&oldid=837697240.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Taking back the market: An auditory dérive through Pueblito Paisa

Dérive (“drift”) in psychogeographic terms, suggests to derive the meaning of a place by passing through its varied ambiences with a playful and constructive awareness of the space and the encounters which it facilitates (Debord 1958). The concept offers a lens through which I will explore microclimates within the Seven Sisters market in Tottenham. My approach to this study was heavily influenced by spacial theorists such as Henri Lefebvre and David Harvey, whose book “Rebel Cities” I happened to be reading at the time of discovering the market. Pueblito Paisa, strongly resembles Harvey’s idea of a “microstate”, which he describes as an autonomously functioning fragmented state, that is born out of the stark polarization of wealth in highly urbanized cities (Harvey 2013, p.15). In the market, I’m also reminded of the concept of heterotopia, which according to Foucault, is a non-hegemonic space of “otherness” and, in the case of Pueblito Paisa, illustrates the result of social heteronomy, a product of class systems within urban capitalist centers. In this heterotopia however, “ethnic, gender and language inequality are key factors in encouraging agency and entrepreneurship which contribute to a sense of belongingness, identity and self-representation” (Roman-Velazquez 2013).

This fieldwork project, in the shape of diary entries and a sound map, reflects an exploration of the market through dérive. It aims to shed light on the complex social fabric that forms Pueblito Paisa’s community and illustrate the important role that such communities play in today’s urban context.

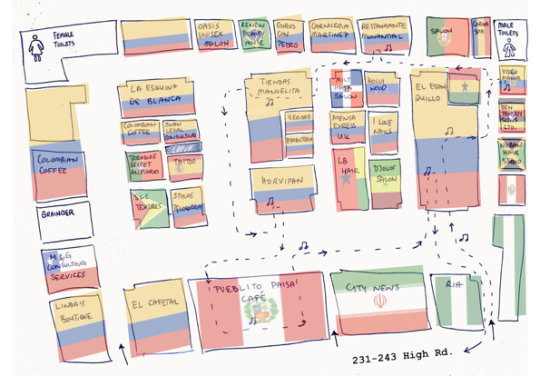

The market (When referring to the market, the names “Latin Village”, “Seven Sisters market”, and “Pueblito Paisa” are used interchangeably.)

Latin Village, located at 231-243 High Rd., contains 39 shops, of which 23 are owned or leased by Latin American retailers (Roman-Velazquez 2013). After Elephant & Castle in Southwark, The Seven Sisters market has the second highest concentration of Latin American business in London (Cabrera 2017). Since 2004, Haringey Council and Grainger development company have been negotiating a regeneration scheme for the area which requires the demolition of the market to make way for 196 non-affordable residential units and 40,000 sq. ft of retail space. Although the developers promise to provide a new long term home for the Seven Sisters Market within this space, the market community fears that it will disintegrate and be unable to afford the rent in the new development (https://tottenham.london/WC).

1. December: My first visit to Pueblito Paisa

I’m sitting in Latin Village’s Peruvian restaurant, “Pueblito Paisa Café”, which looks out on to the Seven Sisters station, allowing a glimpse of the outside world and reminding me that I’m in London. The restaurant is the only place I’ve spotted any other “gringxs”, by which I’m referring to people like myself. Regarding most of the market community is Latin American and speak little to no English, I completely forget my geographic location.

Music is ubiquitous. Almost every shop has its own speakers, playing a selection of Bachata, Salsa, Merengue and Cumbia tracks. Multiple tv-screens hang above the aisles, displaying the, mostly Youtube, playlists. Music is a vital element of the market’s soundscape and its impact on people’s uplifted mood is striking. Conversations are interrupted by familiar tunes, when spoken dialogue turns in to a song, whistle or dance. While wandering through the market like a tourist, I meet Alejandro Gonzalez Gortazar, a Cuban journalist and artist who’s been in the UK for 10 years and has known the market equally as long. He’s helping his friend Fabian, who owns the restaurant “Monantial”, with renovations. Having heard that the market would soon be moved to a temporary location, I am surprised to see people investing time and money in improving a space which developers were threatening to demolish. He happens to break for a cigarette so I take the chance to approach him and introduce myself, hoping he would be able to tell me more about the market. Luckily, he’s eager to speak and begins to talk about Pueblito Paisa’s foundation. According to Alejandro, a group of Colombian immigrants discovered the market about 20 years ago, which then was a half vacant market run by mainly African traders. Noticing they could rent stalls for cheap, they took their chances and started businesses, sending out for kin in Colombia to join in on the opportunities.

All of the market’s stalls have a commercial purpose, but still people seem to be using the space as a community center. There’s a notion of informality and inclusiveness at Pueblito Paisa which allows the general public access to and usage of the space without the pressure to consume or spend money. I think that markets function as important places of integration and solidarity for diverse communities and vulnerable people, where they can find affordable (and sometimes even free) food, social networks and even job opportunities. So why talk about Pueblito Paisa? And why through my eyes and ears, a gringa who has no prior connection to the market or the Latin American community.My sense of “rootlessness”, having been raised in Austria by a Canadian mother and an Iraqi father, has sparked my interest in the formations of “homes away from home” by immigrants and displaced peoples. At Latin Village, sound strikes me as one of the most powerful stimulants in recreating this sense of home. The omnipresence of Latin-American music, Spanish speaking voices, the sizzling of empanadas in the deep friers. Modern technology has enhanced the mobile notion of sound, allowing displaced people to reclaim space through sound and reestablish a sense of “home” wherever they go.Pueblito Paisa offers a fascinating location to study sound’s capacity to communicate impressions of a vibrant community’s social dynamics which is experiencing a period of transition. The Seven Sisters regeneration plans will uproot a well established community and possibly eliminate its collective memory. All I feel that my project can achieve is to exhibit the importance of this market to the livelihood and wellbeing of a community which is overlooked by developers interested in little more than reproducing capital wealth. To create documents that will allow the continuation of Pueblito Paisa’s existence, if only in people’s memory.

6. December: Second visit with Rita

(Screenshot taken of Seven sisters market through Google Maps Street View)

We’re sitting in Pueblito Paisa Café’s conservatory again, juxtaposed between two realms, Latin Village and Seven Sisters. The market is invisible, hiding in plain sight behind trees and vegetable vendors on High Rd., making it hard for passersby to assume what lays behind. This invisibility has offered the community a safe place to establish and express itself freely but the market’s lack of visibility has also made it hard for the community to gain the support they need to protect it.

This time with Rita, my Spanish speaking friend who’s offered to help with translation, we meet Fernando and his colleague Nixon of El EstanQuillo, Pueblito Paisa’s most dynamic hang-out, functioning as a grocery store, butcher, bakery, café, bar, and dance club. Nixon is a baker from Colombia who came to London and found work in Fernando’s shop two years ago. The space is a melting pot of sounds, where the noise of a juice mixer blends with Colombian christmas music and the chopping of meat. All the while kids, sipping on their hot chocolates, watch their parents dance with Corona bottles in their hands. Just across the aisle, we find Fabian from “Manantial”, replacing the carpet in front of his restaurant, completing the renovation process that Alejandro started last week. Later I find out through Mirca Morera, the founder of the Social Enterprise Latin Corner UK and one of the leading women fighting to save the market and protect the rights of its traders, that Fabian is a victim of the 7/7 bombings and is currently facing eviction charges on false accusations by the council appointed market facilitator, Jonathan Owen.

Just next door is the salon of a lovely Portuguese hairdresser, who is repainting her storefront and invites us to the reopening of her shop the following Saturday. Mirca will later tell me that she has a heart condition relies on the income and stability that the market can offer her, to ensure her health and livelihood. While she chats to us about family and work, her warm and welcoming spirit makes us feel like she’s always known us. Some in the market recognize me and wonder how I am and where I’ve been. Many traders tell me that their customers to them are friends before potential income-sources. “When a frequent customer doesn’t show up for a couple of days, I begin to worry and, if possible, call them to see if they’re alright”, Victoria Alvarez tells me. Vicky is the president of the association El Pueblito Paisa Ltd, owns two businesses in the market and is the face of the current crowd-funding campaign striving to raise 7,500 pounds towards a legal defense fund to preserve the market and its community.

9. December: Third visit with Paul

We’ve decided that Latin Village reveals elements of the failing system we live in.

Pueblito Paisa succeeds in protecting individuals who have fled economic hardship and possibly persecution, by offering them job opportunities and social networks. Rather than just facilitating economic reproduction, the space functions as a safe place guaranteeing the community’s happiness. Here, individuals do not self-maximize for the sake of reproducing their own wealth, but rather self-sustain for the sake of reproducing their own and community’s happiness. In an ideal reality, where governing systems enforce city development to improve the life quality of its citizens, particularly minorities and the most vulnerable, the protection of spaces, like Pueblito Paisa, woul be of highest priority.

Upon arriving at the market we head straight to El EstanQuillo to visit Nixon and Fernando. “Bomba En Navidad” by Richie Ray and Bobby Cruz, who Nixon adores, is playing while customers dance beneath the christmas decoration. We go over to see the Portuguese hairdresser who’s celebrating the reopening of her shop. She invites us in for snacks and drinks and to dance to some Reggaeton tunes together with her family and friends. After getting in touch with Latin Village UK over Facebook in the hopes of learning more about the organisation’s activities, Mirca invites me to the market to chat this evening. I find her sitting at her little community desk which she has set up in her stepfather’s video and music shop, “Videomania”. Her table is surrounded by artwork made by children from the market community, for who she organizes regular field trips to universities and museums. A trained educator, Mirca adores and is adored by the market community. With slogans and hashtags like, “take the Victoria line to Latin America”, she’s targeting the anglophone community through Latin Village UK’s campaigns. She’s also taken her plead to the UN triggering an intervention by the UN working group on business and human rights. Mirca and Vicky Alvarez seem to be the informal mayors of the market. They know the names and stories of everyone and fight restlessly to make their stories heard. They tell me that half of Pueblito Paisa’s business owners are female and that the market plays an important role in offering women, especially from Latin America, the opportunity of employment or entrepreneurship. These opportunities have raised their self-esteem and empowered their agency in a city which makes it extremely difficult for migrants, particularly female, to integrate into the job market.

Above: Images from Latin Village UK’s crowdfunding campaign: https://www.instagram.com/savelatinvillage

Below: Video still from Latin Village UK’s campaign video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=luEy65Y5n7s

16. December: Fourth visit alone

I’m on the tube heading back South, siting across from three men who left the market the same time as I did. They recognize me, smile and start speaking to me in Spanish, the market’s notion of community clashing with London underground’s nature of anonymity. It’s an incredibly precious feeling, realizing that inside this vast city, a sense of familiarity amongst strangers is possible.

Back at the market, I sit inside Vicky’s salon, chatting to her and Mirca while outside the market begins to fill up for an evening full of music and dance. Vicky tell her life story, of how she arrived in London from Colombia about 30 years ago. It was only until her father was murdered due to the Colombian conflict, that the UK granted her asylum and she was able to flee the country. She lost four of her siblings during the war and has undergone immense trauma, making her a very anxious person today. She tells me that the current market facilitator, Jonathan Owen, uses harassment to tear apart the market community and make way for developers to start working on the regeneration project. Many community members are Colombian refugees and suffer from PTDS. Vicky fears for the mental health of the community and is convinced that Jonathan’s bullying and threats may evoke anxiety and flashbacks of the terror they lived through in Colombia. “We are not just a shopping market, we are like a psychological clinic, a therapeutic market.” (Roman-Velazquez 2013). I am deeply humbled by Vicky and Mirca, who fight day and night to protect the market. Not to ensure their own livelihoods, but to defend their community’s right to existence, free cultural expression, and mental health and stability.

In the bathroom, which goes dark after 9PM when electricity is cut, I meet Lorena who is holding up her phone to illuminate the bathroom. She notices that I’m new to the market and asks me how I like it here. “I love it, what about you?”. She laughs, “me? I am Colombian, of course I love it! It’s the best place in London”. We continue to chat about life in the city while she holds the flashlight over the sink while I wash my hands.

Pueblito Paisa is a place of casual heart-warming encounters like this, a public space in its purest form, which is open to all and is shaped by the diverse people who use it. These are the spaces we need most in increasingly urbanizing cities like London where urban commons are reclaimed by profit-driven developers who are privatizing the city for their own economic benefit. It is places like Latin Village that remind us that cities can exist for people and not only for profit. It is places like this that make me feel “at home”.

“Dériving” in Pueblito Paisa: A sound map

Follow the link for the soundscape and its description (to trace the dérive, refer to the map above):

https://soundcloud.com/emily-sarsam/pueblito-paisa-an-auditory-derive

Follow the link for a Spotify playlist of music heard at Pueblito Paisa:

https://open.spotify.com/user/1111197818/playlist/1y5DaUkpu0nnBbowCwv2hM

References:

Cabrera, Maria. “We need to recognise the latinx community in the UK: Save Pueblito Paisa.” http://www.gal-dem.com/latinx-community-pueblito-paisa/ (accessed December 30, 2017)

Costa-Kostritsky, Valeria. “‘I won’t be displaced again’: the fight to save London's latin market.” https://www.opendemocracy.net/5050/valeria-costa-kostritsky/fight-to-save-london-latin-market (accessed December 30, 2017)

Debord, Guy. “Theory of the Dérive”. 1958. http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/2.derive.htm (accessed December 30, 2017)

Harvey, David. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. Paperback edition. London: Verso, 2013.

Roman-Velazquez, Patria. Valuing the work of small ethnic retail in London: Latin retail at E&C and Seven Sisters. Presentation given at Department of Sociology, UCL. 23 March 2013. https://latinelephant.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/valuing-small-ethnic-retail-space_ec.pdf (accessed December 30, 2017)

Photographs & Map:

All Photographs and the map are my own.

Photo 1 (cover) : An aisle in Pueblito Paisa, 2017.

Photo 2: El Pueblito Paisa Café, 2017.

Photo 3: El EstanQuillo, 2017.

Photo 4: Tiendas Manuelita, 2017.

Photo 5: Horvipan, 2017.

Photo 6: El EstanQuillo, 2017.

#latin village#pueblito paisa#colombia#london#tottenham#haringey#gentrification#soundscape#seven sisters

1 note

·

View note

Text

Women on the London Jazz Scene: Inspiring a generation of female jazz musicians

In this paper I will be discussing gender dynamics in the context of the current London Jazz Scene. This scene offers an interesting field to explore the powerful roles that women, such as Yazz Ahmed, Emma Jean-Thackray, Alya Al-Sultani, Nubya Garcia to name a few, are playing in inspiring a new generation of, especially female, jazz musicians. The idea to write this essay was inspired by my participation in the symposium “Making the changes: A powerful symposium for women in jazz”, which Issie Barrett organised in December 2017 at the Southbank Center and assembled over 70 people to speak about the current status of women in jazz. I feel it’s important to question the difficulties women and girls face when deciding to pursue a career in jazz, considering the art form’s historical importance in functioning as the voice of the oppressed, communicating the discriminatory practices of everyday life, and improvisation behaving as the ultimate symbol of freedom. One of my interviewees, Al-Sultani, believes that some actors in the jazz scene feel threatened by proactive and outspoken women. In order to prevent female jazz artists from becoming empowered by the sector, these actors have tailored the scene to function as a hostile environment. This reality clashes completely with Alya's interpretation of jazz as “politics of freedom”. To better understand this dichotomy, I will be drawing on the writings of scholars such as Ingrid Monson and especially Sherrie Tucker, who’s book “Big Ears: Listening for Gender in Jazz Studies” offered a valuable reference while exploring historical gendering in jazz and its influence on shaping the entire culture around it. In order to gain first-hand insight to current debates on gender in the London jazz scene I conducted interviews with Lizy Exell (English jazz drummer, member of the collective Nérija) from Jazz Herstory, a new web platform set up in July 2017 which seeks to address gender equality in Jazz, and Alya Al-Sultani, a vocalist and artist who released “Collective X”, a project which explores race, identity, and the black and minority ethnic experience through music. A lot of my opinions and views can be traced back to participatory observation during lectures, concerts and informal discussions with jazz musicians and enthusiasts alike.

The risks of gender-blindness and essentialism in jazz