Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Notes on Ian Leslie’s John & Paul: a Love Story in Songs.

#5: "You're not still angry with me, are you, Mimi?"

I love the way Ian Leslie writes about the formative influences of Julia (John Lennon's mother) and Mimi (his aunt and de-facto parent). It's commonplace to point out that John was a very all or nothing, hot and cold, tough but tender person. Until I read John & Paul: a Love Story in Songs, however, it never occurred to me to connect John's yin and yang personality to the two vastly different models of adulthood and femininity that Julia and Mimi embodied. “In 1957", writes Leslie, "it must have felt to John Lennon that life was about choosing between these two paths – between two ways of being a person. And then along came Paul.” (p.18) Does that imply that Paul McCartney represented some rare hybrid of both beasts? A musical sphinx with Julia's artistic flair and sense of adventure, but who could also match Mimi's wit and thrift?

Perhaps Leslie is saying that Paul confronted John with a hitherto unknown possibility, a third option that was neither Julia nor Mimi, but an escape into perpetual lost boyhood. Either way, Leslie's recognition that two colossal and contrasting female figures bestrode John's young life goes some way to explaining how much he responded to the world in black and white terms. John was child-like in his trust and adoration of those who, like Julia, projected a louche form of charisma (Magic Alex, Maharishi, Allen Klein); he was also shockingly rude to conventional authority figures (Lee Eastman), but in a way that abnegated responsibility and carried the expectation of a parent's forgiveness.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes on Ian Leslie’s John & Paul: a Love Story in Songs.

#4: Lennon's restless melodies.

When describing the difference between Lennon and McCartney's musical styles, it's common for people to point out that Paul wrote beautiful melodies yoked to daft lyrics while John tended to hit one very insistent note over and over again, the better to deliver his lyrical litanies.

This is too simple to be true. George Martin points out in The Beatles Anthology that John could write some wonderful music and Paul could write some wonderful words. There are many examples of a 'John' song in which a melody shifts restlessly, even wildly, around its singer's vocal range, and in a way that projects uncertainly, anxiety or a loss of control. Think of the verses of 'Girl' or almost all of 'Strawberry Fields Forever'. These are songs in which a singer struggles to find his musical footing at the same time as as he's trying to master a volatile emotional or psychological state. Ian Leslie offers a great early example of this quality in Lennon's songwriting: ‘If I Fell’. This is a song, he writes, in which "a lurching chord change makes us uncertain about where we stand within the song’s harmonic world. John’s voice leaps up (and help me …) to a note that’s so high in his register that he almost breaks on it, before coming back gracefully down the scale, via each syllable of ‘understand’. The intro to ‘If I Fell’ makes us feel Lennon’s uncertainty as well as hear it in his words. Falling in love it shows us, starts with falling.” (p.107)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes on Ian Leslie’s John & Paul: a Love Story in Songs.

#3: Perspiring Geniuses

One of the things that Ian Leslie does best in John & Paul is explode myths about the Beatles' creative process. “The origin story of ‘Yesterday’ is often told as an example of divine inspiration," he writes, "because it came to McCartney in a dream. But it is also an example of what the science writer Steven Johnson calls a ‘slow hunch’: an idea that takes its time to ripen and requires a lot of work to realise.” (p. 122)

A maxim commonly attributed to Thomas Edison makes the same point: genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. The extent to which this applied to Lennon-McCartney songwriting is important to consider if we want to understand just how they did what they did. I appreciate that revealing a magician's secrets destroys the appeal of illusion, but we're not talking about tricks that anyone can learn how to do; we're talking about how two men created some of the greatest songs of all time, not just better than those of their peers, but easily better, better by far. If their process involved chipping away at lyrics and chord progressions, trying out different arrangements and seeing what songs sounded like if they began with the chorus and jettisoned the middle eight, I want to know about it. I'm fascinated by this stuff, and I'll probably end up revering Lennon and McCartney more for their dedication to their craft.

Both Lennon and McCartney have been guilty of obfuscating and oversimplifying their composition processes, perpetuating the belief that even their most inspired songs took as much time and effort to write as they do to hear ("fiddle around in C for a while and hey, presto, you've written 'Let it Be'!). To be honest, I wish they wouldn't. If you believe that little thought or energy went into their work, it's easier to dismiss them as savants with a lot of luck and little between the ears save catchy tunes. Paul McCartney's reputation, at least, has suffered from this. Leslie’s careful consideration of how iterative and painstaking his creativity actually was demonstrates that moments of great inspiration still require a sustained perspiration that should be acknowledged and admired.

Everyone knows that ‘Yesterday’ was the only song that Paul ever dreamed, but not many know how long he spent toying with the tune, playing it to anyone who'd listen, studying their reactions, asking for their thoughts, subbing in dummy lyrics about scrambled eggs before the rights words to match his tune's melancholy mood slowly emerged. 'Yesterday' is a prime example of where music and lyrics cohere as inseparable sides of the same artistic coin. I can't hear the tune without thinking of the words, and I can't read the words without hearing the tune. Their brilliance testifies to McCartney's formidable talent, but they should impress their listener as evidence of creative muscles that had grown harder, faster, better and stronger through use, and not through sitting and waiting for the muse to strike. 'Yesterday' is so perfect that it sounds effortless, a low-hanging fruit that McCartney plucked with two idle fingers one lazy Sunday afternoon. It's the very appearance of effortlessness, though, that should tip us off about the considerable effort it took to achieve this effect.

Leslie is also bang to rights in identifying the same slow gestation and dogged pursuit of perfection as qualities vital to John Lennon’s creative process, however much he would vaunt certain songs as the children of immaculate creative conception. A case in point is ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, clearly one of his most distinctive and ground-breaking works: “Lennon has a reputation for being a visionary artist and what we expect of a visionary is that their ideas arrive fully formed, thunderbolts from the blue. ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ began as an odd-shaped pebble that Lennon rubbed away at patiently until it began to glint.” (p. 180) Anyone who's listened to the series of fragments that were combined, separated and re-combined over the last months of 1966 until they became the song we all know and love will agree that this is true.

Lennon and McCartney liked to give the impression that songs flowed from their guitar strings like the Mersey flows through Liverpool; it perpetuates an appealing Romantic myth of genius. The truth was at once more laboured and more accomplished than this myth. Indeed, it is their sustained creative concentration and their unerring ability to separate the wheat from the chaff that we should admire most about the Lennon-McCartney partnership.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes on Ian Leslie’s John & Paul: a Love Story in Songs.

#2. Noddy's Adventures in Toyland

Ian Leslie writes that the song ‘Penny Lane’ “hints at and subverts England's deep cultural memory, imaginary or otherwise, of an orderly, serene Edwardian world, before war and decline despoiled it.” (p.189) I know the world that Leslie’s referring to. It’s there in the poems Philip Larkin wrote at the same time as the Beatles made their music, poems such as ‘MCMXIV’ (1960) and 'To The Sea' (1969):

“The crowns of hats, the sun On moustached archaic faces Grinning as if it were all An August Bank Holiday lark. And the shut shops, the bleached Established names on the sunblinds, The farthings and sovereigns, And dark-clothed children at play Called after kings and queens, The tin advertisements For cocoa and twist, and the pubs Wide open all day...” "Steep beach, blue water, towels, red bathing caps, The small hushed waves’ repeated fresh collapse Up the warm yellow sand, and further off A white steamer stuck in the afternoon."

It’s a world that lyric poetry evokes particularly well. It may only have been a matter of time, then, before a bookish and ambitious Beatle chose to set a comparable 'lyric' to music.

Leslie also makes an apt comparison between Paul McCartney and René Magritte in his discussion of ‘Penny Lane’. Magritte’s paintings, like McCartney’s music, “are easy to like and superficially easy to comprehend, yet inscrutable and unsettling at the same time. It is the art of the uncanny: the real made subtly unreal.” (p.187) Leslie is right, though I think there’s a little more to it, and what there is connects to the point above about remembrance of things past.

You wouldn’t know it by the song’s jaunty summery sound, but I think of ‘Penny Lane’ as an elegy. It’s not lachrymose, but its animating spirit is one that all elegies share: the desire to recapture a lost object. In this case, McCartney conjures a prelapsarian England too far back in time to have been something he experienced, but one that he inherited through shared cultural memories. I think it was one he identified with, melding it with his own dreamy recollections of boyhood. Most of us are prone to romanticising our childhoods; just think how much stronger the temptation must have been for a man who precipitated a cultural shift that couldn’t be walked back. Stepping into Beatlemaina must have felt like closing the door on a version of himself that could only then be glimpsed in dreams and diaphanous music. It’s exactly this yearning for a former self that I hear in the ethereal ‘Ram On’ from McCartney’s 1971 album RAM.

So, ‘Penny Lane’ may be regarded as elegiac because it aims to make absence present. It may also be considered elegiac for an equal but opposite reason: it has the effect of making presence feel absent. The sunny oasis of barber, fireman, roundabout and nurse are all conjured in living colour by McCartney’s synesthetic mind, but the harder you stare at them the more they resemble Noddy’s Toyland: shiny and attractive, but also faintly macabre, or ‘very strange’ as the song puts it. Leslie picks up on this disquieting insubstantiality in the song’s imagery: “… the singer tells us that Penny Lane is in his ears and in his eyes. But the singer is also telling us that he isn’t there … he’s … remembering a place that will never be as real to him as it once was.” (p. 189).

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes on Ian Leslie's John & Paul: a Love Story in Songs.

#1. "...it became petty, but the manifestations were on each other, because we were the only ones we had."

Ian Leslie offers his reader a really interesting consideration of the tension that escalated between the Beatles over 1968-1969. He does it by drawing attention to the fact that their acrimony also represented a kind of ‘phase shift’, one that fuelled their creativity, rather than constraining it. Just as they had exchanged leathers and quiffs for collarless suits and mop-tops, and then went on to exchange these for militaristic uniforms and Edwardian facial hair, the Beatles sat in their escalating squabble as if it were a skin they expected to shed.

Some have questioned why the Beatles didn’t take any substantial time off after the Herculean effort it took to produce the double 'white album'. Leslie suggests that the answer is their sense of having entered another period of fertile creativity: “From late 1968 to early 1969 McCartney wrote many songs that ache with yearning for home: songs for the end of a journey – ‘Two of Us’, ‘The Long and Winding Road’, ‘Let it Be’, ‘Get Back’, ‘Golden Slumbers’. These songs seem to emerge from an intimation that the dream he and John created in Liverpool was coming to an end … As they came apart, they increased their rate of production … Making music together was their way of processing emotional turmoil” (p.277-291).

One of the reasons the band members submitted themselves to the slow-motion crash of their break-up without trying to resist, ignore or control it, is that submission, or at least creative openness to all possibilities, was their superpower: accepting, succumbing, going with the flow and trusting their child-like faith that 'something will happen'. The Beatles’ music is so fecund and diverse because it doesn't try to fix mistakes; it explores accidents. This is what the band were doing as the momentum of their break-up gathered. They used their turmoil to fuel their creativity, hopeful that this would lead them toward the next spectacular re-birth. There’s real pathos to this: even as they knew they were being pulled apart by circumstances beyond their control, they each strengthened their grip on the only security blanket they had – each other. Perhaps this is the reason why Abbey Road sounds so unified and happy, a final tribute to the Beatles by the Beatles themselves. As Leslie says, “It’s like the curtain call of the musical that John and Paul never wrote.” (p.312)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

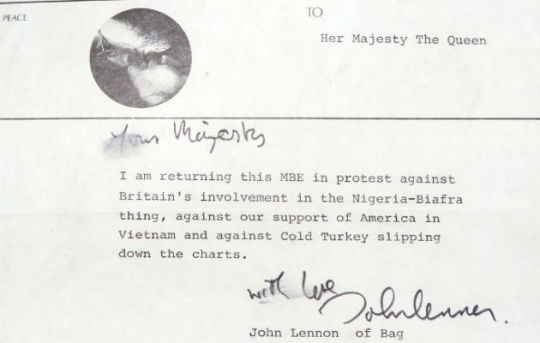

'Now and Then', 'Here Today' and subjunctive creativity

From announcement to release and beyond, biographical speculation has attended ‘Now and Then’, the momentous ‘last Beatles song’. I understand the compulsion to speculate: Lennon’s lyrics are inchoate, but they identify an unnamed subject as the reason for the singer’s success and as the source of his fortitude:

I know it's true It's all because of you And if I make it through It's all because of you

youtube

These opening lines suggest that Lennon is not the hero of his own life; instead, they attribute that station to someone else. Who? Yoko Ono? May Pang? Paul McCartney? These are clear possibilities that fans, bloggers and podcasters have enjoyed considering. It was in the wake of such consideration that Sean Lennon (John’s second son) was moved to tweet his thoughts on the subject:

“If you listen to my dad speak about lyrics, it’s clear he never felt any song was necessarily about one thing. Songs are not essays. Poetry is not journalism. Art is like life - multilayered and elusive.”

With customary brevity, Twitter (or ‘X’ as it’s decided to call itself) proved the ideal platform from which to make an obvious but surprisingly overlooked point: however autobiographical a song may be (or appear to be), it always involves elements of artifice that distance the creation from its creator. A song is never wholly self-inspection or self-revelation. At one level, this is because autobiographical content must always be shaped by musical conventions that exist independent of it. In the case of ‘Now and Then’, these conventions include a questioning A Minor-E Minor verse structure and a more assured G Major-D Major chorus that answers the questions posed by the verses. It’s a classic Beatles trick, taking a sad song and making it better.

Another reason why ‘Now and Then’ can't exist solely as a spontaneous overflow of powerful emotion is recognised in Sean’s comment that his father ‘never felt any song was necessarily about one thing’. To put this another way, Lennon’s intention in composing ‘Now and Then’ was less to speak to or with the song’s subject than it was to achieve the composition itself. Ono, Pang, McCartney or all of them may have been on his mind as his fingers shifted, searchingly, from A Minor to E Minor, but it’s likely that Lennon put the stuff of life into the service of his creativity, rather than using creativity as a tool to resolve issues in his life. Musical therapy may be a felicitous by-product of composition, but I suspect that it wasn’t the prime motivator. In the same way that an Olympic sprinter is trying to win a race more than he’s trying to keep fit and healthy, Lennon’s chief desire in composing ‘Now and Then’ was probably (and simply) to write a good song.

None of this should diminish the song’s meaning or impact. Indeed, these aspects are enhanced when you appreciate them as dynamic (not static) and universal (not local). As Sean Lennon put it, art is ‘multilayered and elusive’ and all the better for it.

If you’re not convinced, then consider another example of creativity's searching, elusive qualities: Paul McCartney’s ‘Here Today’. It’s a song that the composer freely (and frequently) admits to being for or about John Lennon. Even in this relatively direct epistle ‘from me to you’, however, there are still reasons to delineate the ‘I’ who sings from the ‘I’ who is sung about; to recognise that, however autobiographical the song’s contents is, there are fictionalised elements that characterise it as a work of art more than a vérité documentary.

As stirred with emotion as McCartney no doubt was in the wake of Lennon’s 1980 murder, it was when stumbling upon an unusual E Minor 6th chord that ‘Here Today’s composition began – from a musical pang as much as an emotional one. As with ‘Now and Then’, there’s an unresolved and questioning quality to the chord(s) that lays the foundation of the song's creative space. The E Minor 6th chord is an inkling that the rest of the song goes on to explore. The apt word to describe the mood it conjures is ‘subjunctive’, a term employed by grammarians to describe a verb form that represents an act or a state of being not as fact, but as a conditional or possible that is experienced emotionally.

The song’s lyrics are also drawn from this mood. They begin mid-sentence, as though trying to enter the delicate musical space unobtrusively, via a side door:

And if I said I really knew you well What would your answer be If you were here today?

They are subjunctive because they imagine how a conversation that never occurred might have played out. They draw on McCartney’s intimate knowledge of Lennon and they reveal much of their composer’s psychology, but these aren’t leveraged to document reality; they’re employed to stage a scene between two men as semi-fictional versions of themselves.

youtube

The novelist Martin Amis once explained the uneasy relationship between fiction and reality this way: “You don't write about what happened, you write about what didn't happen.” That is exactly what McCartney does in ‘Here Today’, imagining how Lennon might have responded to words that McCartney should have said, but didn't. ‘Now and Then’ does much the same thing, achieving an artistic reunion between Lennon and McCartney where – and perhaps because – no comparable reunion was ever quite achieved in life.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Hard Day’s Midsummer Night’s Dream: The Beatles Play Shakespeare

In February 1964 the Beatles and their small coterie were in New York, having ‘invaded’ via John F. Kennedy International Airport (newly-renamed in the wake of the President’s November 1963 death). 5000 screaming fans greeted them as they alighted Pan-Am flight 101, and pandemonium followed them to the Plaza Hotel, reaching fever pitch as they performed live on The Ed Sullivan Show two days later.

Despite the hurricane quality of their first visit to the United States, their manager Brian Epstein took the time to meet with Jack Good, a British television producer for Rediffusion London (which had also just changed its name). It was fortunate for Good to have been squeezed into Epstein’s tight schedule. Indeed, Epstein may have given him the time of day on the basis that he, too, was a trail-blazing impresario of British rock ‘n’ roll acts: Tommy Steele and Billy Fury owed part of their success to Good’s management. Epstein was impressed enough that he agreed to a Beatle-themed television special, suggesting that Good himself produce the show (a point that he would later press during negotiations with Rediffusion). Another deal-breaker for Epstein was that the special must serve as an introduction and endorsement of other NEMS (Epstein’s company) acts. With one eye on American distribution of the special, Epstein also requested that Murray ‘The K’ Kaufman act as compare. 'K' was a prominent New York disc jockey and one of the lucky few ushered into The Beatles’ inner circle on this transatlantic visit.

Rediffusion agreed to all of Epstein’s terms (including NEMS ownership of world distribution rights) and provisionally entitled the special John, Paul, George and Ringo. Last-minute name changes must have been part of the 1964 zeitgeist, however. In addition to the re-christened JFK International Airport and the self-styled Rediffusion London, Good re-named his Beatles show Around The Beatles, a title that was likely inspired by the semi-circular design of the set built for it.

The special was rehearsed on April 18, 25 and 27 before taping on Thursday 28 April. The Beatles did not perform any songs until the second half of the hour-long show, though their (mimed) set was notable for featuring the only televised medley of Lennon-McCartney compositions the band ever ‘stuck together’ (to borrow Paul McCartney’s phrase when introducing the sequence). ‘Love Me Do’, ‘Please Please Me’, ‘From Me To You’, ‘She Loves You’, ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ and ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’ are the songs in question.

youtube

The majority of the show’s first half was given over to a ‘variety-hour’ assortment of supporting acts, including Millie, Long John Baldry, Cilla Black, P. J. Proby, Sounds Incorporated and The Jets (an American dance troupe). Many of their performances look and sound quite dated now, especially when set against the timeless vitality of The Beatles. Indeed, one song in which Sounds Incorporated execute a neat series of dance steps recalls the unified choreography of The Shadows, an act which had bemused The Beatles prior to their success.

One of the sequences that sets the show apart from television specials of the era is the unique means by which Good chose to introduce The Beatles to their audience. Rather than start things off with a big musical number (as might have been expected), he capitalised on the band's humour and charm by having them perform a liberally-edited version of Act 5, Scene 1 from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the celebrated play-within-the-play in which Quince, Snout, Bottom, Flute, Snug and Starveling (the ‘rude mechanicals’) perform a hilariously inept version of Pyramus and Thisbe’s tragic love story, all the time struggling valiantly against the mocking interjections of the play’s ‘noble’ characters (Demetrius, Hermia, Lysander, Helena, Theseus, Hippolyta and Egeus). It is not clear how and why Good seized upon this idea, but it too may have been in response to the semi-circular design of the set on which the band played, echoing as it does the tiered three-quarter circle of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. It may also have had something to do with the fact that the Beatles rehearsed the show on April 18 and 25, either side of the anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth and death (April 23), an auspicious date that Ringo Starr noted when interviewed by Murray ‘the K’ on set.[1]

youtube

Whatever the reason for the special's unusually theatrical opening, its effect is inspired, playing wonderfully to the anarchic comic strengths of the Beatles’ collective identity. Clips of the scene are prevalent on the internet (including one surprisingly effective colourisation), but they are often misrepresented as a ‘parody’ of Shakespeare in comments and captions. It is true that the Beatles play fast and loose with the script, interjecting their own one-liners throughout, but the spirit of their performance is remarkably consistent with the intended tone of the scene which, it should be remembered, is already a parody. In this case, Shakespeare mocks the representation of tragic love in Elizabethan verse plays such as his own Romeo and Juliet, which was written either immediately before or after A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ playlet is intended to be chaotic and inept, performed as it is by a group of enthusiastic but unsophisticated artisans who find themselves thrust into a world of power and privilege they do not fully understand. When considered this way, the scene and its characters are apposite to the position The Beatles found themselves in at this point in their career: suddenly and unprecedentedly successful working-class lads from an industrial backwater taking some of the starch out of the stiff cosmopolitan shirts they encountered in London and New York. The kind of ‘hooray Henry’ infamous for snipping locks of Beatle hair might have applied Puck’s description of the mechanicals to The Beatles as they descended upon his little patch of the world: ‘What hempen homespuns have we swagg’ring here…? (3.1.65)’. The Beatles' swagger is more knowing and cheeky than the rustic gait of Shakespeare’s rude mechanicals, but its effect is very similar: if Bottom or Quince were transposed to the 1963 Royal Variety Performance, they too might have requested that the poorer audience members clap their hands while the rest rattled their jewellery.

Indeed, the effect of the Beatles on the stifled culture of Great Britain in the early 1960s might be considered analogous to the effect that ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ has on the Athenian nobility who are confronted by it in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Writing of the intended effect of the play-within-the-play, Marjorie Garber argues that '… performed by social inferiors for their putative betters, it confronts the themes, aspirations, and pretensions of the aristocrats and comments on the larger play that contains it.'[2] Over the course of the scenes in which the mechanicals rehearse and then deliver their performance, Quince (their self-appointed manager) tries and fails to maintain control over an increasingly chaotic band of would-be entertainers who add and subtract from his script, question his decisions and ignore what they are supposed to be doing when something more interesting turns their heads. Perhaps Good had seen footage from A Hard Day’s Night (completed but not yet released at the time Around The Beatles was taped) and perhaps he was struck, like the author of this article, by the parallels between the mechanicals and the semi-fictionalised Beatles of the silver screen, both of whom effortlessly frustrate each authority figure they encounter.

The chaos of the rude mechanicals’ Pyramus and Thisbe is echoed in the performance the Beatles give of it, which seems always to be on the verge of collapse. The ‘heckling’ interruptions of some audience members add to this effect and may seem to be a strange addition of Good’s, but they are also in keeping with their source material. They are a substitute for the on-stage audience of principal characters constantly interjecting their criticism of the mechanicals’ performance in Shakespeare’s play. Hippolyta, for instance, exclaims ‘This is the silliest stuff that ever I heard!’ [5.1.207]. The tone and effect of the heckling The Beatles contend with is strikingly similar to that present in Shakespeare’s play. Stephen Greenblatt says of the mocking audience in A Midsummer Night’s Dream that ‘we are incited at once to join in the mockery … and to distance ourselves from the mockers’[3], something you feel in Around The Beatles when one wag shouts ‘Go back to Liverpool!’ We recognise that the band are uncomfortable in the world of Elizabethan theatre, but we are on their side when a contingent of London audience sets against them.

There are other parallels between The Beatles’ story and A Midsummer Night’s Dream that are worth pointing out. At the time he wrote the play, Shakespeare was either working towards or away from the comedy of magic in moonlight, something which appears in earnest throughout Romeo and Juliet but which is also present in the nocturnal sorcery the fairies work in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Marjorie Garber writes that the play emphasises ‘the difference between night, which transforms and changes, and day, which is rigid, inflexible, and associated with law.’[4] The stark contrast between what could be said and done after the sun went down and what repercussions might be made in the cold light of day was certainly one that the four Beatles understood. The nightlife of Hamburg’s Reeperbahn, for instance, was the crucible in which their alchemy was formed: its coloured lights, licentious habits and mind-altering substances are a modern analogue to Oberon and Titania’s shady garden of delights. The effect of moonlight on The Beatles’ creativity took root early and continued to grow throughout their career. As soon as they were given the keys to the kingdom of EMI Studios, for example, their preferred recording hours began late in the day and ended as the sun came up. Indeed, one of the few ‘covers’ they would record in 1964 was Roy Lee Johnson’s ‘Mr Moonlight’, the opening address of which is scream-sung by John Lennon as if he were a wolf howling at the song’s titular subject. The first verse of the song continues:

You came to me one summer night And from your beam you made my dream And from the world you sent my girl And from above you sent us love

This is comparable to the lines spoken to the moon by Bottom’s Pyramus in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In Around The Beatles, it is Paul, dressed as Pyramus, who delivers the first of these lines, the following three of which were cut from the 1964 performance:

Sweet moon, I thank thee for thy sunny beams. I thank thee, moon, for shining now so bright; For by thy gracious, golden, glittering gleams I trust to take of truest Thisbe sight (5.1.261-264).

One of the best jokes staged in ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ is the absurd personification of ‘moonshine’ (complete with a lantern, thorn bush and dog) reluctantly played by the serious-minded Starveling, whose name means ‘undernourished’. In The Beatles’ performance , the character is well-represented by George Harrison, the most gauntly thin Beatle and often considered to have been the sourest (his first song was called ‘Don’t Bother Me’). Shakespeare’s character and George’s public persona are in perfect harmony when, frustrated by the heckling interruptions of the show’s audience, he says:

Look, you! All I have to say is to tell ye that this lantern is the moon, ye see. Got it? I’m the man in the moon, this thorn bush ‘ere’s my thorn bush and this doggy-woggy ‘ere is my dog! [sic][5]

The same rehearsal tape made by Murry ‘The K’ in which Ringo alerts the DJ to the date of Shakespeare’s birthday also includes a moment suggesting that Good knew exactly what he was doing when he cast George as Moonshine. The Beatle can be heard delivering the lines above before Good interrupts him with this note: ‘George, you mustn’t smile at all, you mustn’t sort-of realise it’s a joke’[6]. Clearly, Good knew that Starveling was meant to be a grumpy, frustrated character and that he is funniest when played ‘straight’.

Next to Puck (the mischievous sprite) the best-remembered character from A Midsummer Night’s Dream is probably Bottom (the weaver), the most enthusiastic of the rude mechanicals. He doesn’t appear in the Beatles’ version of Act 5, Scene 1 in any proper sense: it’s true that Bottom plays ‘Pyramus’ in the play-within-the-play, but Paul appears to be playing Pyramus fairly straight too: as a young lover, rather than as Bottom-playing-Pyramus (which wouldn’t make a great deal of sense outside of the play’s larger context). Despite this, Bottom is a character appropriate to Paul. For one thing, he shares Paul’s natural charm and enthusiasm. He also has something of Paul’s desire for control and thirst for the spotlight, wanting to play both Pyramus and Thisbe himself: ‘An I may hide my face, let me play Thisbe too. I’ll speak in a monstrous little voice: “Thisne, Thisne!”’ (1.2.43-44). Bottom's eager versatility is comparable to Paul’s facility with a range of musical instruments that sometimes led him to encroach into his bandmates’ territory. Ringo, at least, would complain of Paul’s tendency to mess with his drums.

In some respects, it is actually Ringo himself who is reminiscent of Bottom: both are the most loveable member of their respective band of entertainers. Bottom is always greeted by his companions with unfeigned joy, and his presence has the effect of defusing tension, just as the three other Beatles would still rally around Ringo when otherwise at odds with each other. Like Bottom, Ringo doesn’t always appear to understand everything that’s happening to him - think of that moment in the Maysles brothers’ What’s Happening! The Beatles in the USA at which Ringo exclaims ‘It’s great to be here in New York! Oh, Washington, is it? Just moving so fast…’[7] Most characteristically, Bottom and Ringo both have an endearing tendency to speak in malapropisms as profound as they are naïve. ‘A hard day’s night’ is a phrase that could easily have issued from Bottom’s lips after hours of weaving work, just as Bottom’s reference to his dream as ‘Bottom’s Dream, because it hath no bottom’ matches the homespun profundity of ‘Tomorrow never knows’.

A more general point of connection between Shakespeare’s play and The Beatles concerns the fact that A Midsummer Night’s Dream had frequently been considered the most suitable of Shakespeare’s plays for children, stuffed as it is with fairies, slapstick and strong rhymes. In 1964, at least, an atmosphere of Victorian-era wholesomeness and whimsy attended it, as though it were a precursor to Peter Pan. Such an unthreatening, ‘family’ appeal suited the neatly-pressed image for The Beatles that Brian Epstein had crafted over 1963. By the time Around The Beatles was taped, The Rolling Stones had entered the British popular consciousness as a more dangerous and pouty alternative to the smiling, chirpy Beatles, reinforcing the latter’s wider appeal.

This, at least, is how the media were encouraged to see things, though the truth was more complex. The Beatles’ genesis on Hamburg’s Reeperbahn belies the squeaky-clean aspect they had cultivated, just as John’s on-stage presence tended to cut through the professional sheen that Paul lent to proceedings. It was in 1964 performances, for instance, that John would often change the lyrics to songs (secure in the knowledge that they couldn’t be heard over the audience’s screams), the coy overture ‘I wanna hold your hand’ sometimes being replaced by the more confronting and sexually aggressive ‘I wanna hold your head’.

Just as there was a suggestive (perhaps even predatory) side to The Beatles if you knew where to look, so too are there more dangerously adult aspects to the desire that seethes beneath the surface of A Midsummer Night’ Dream. Emma Smith writes of the way ‘our schoolroom version’ of the play has polished away its rougher edges (or, if you like, replaced its leather jackets with a shiny, collarless suits):

…the ‘dream’ of the title is more Dr Freud that Dr Seuss, and the vanilla framing device of marriage creates an erotic space for a much raunchier and riskier set of options, from bestiality to pederasty, from wife-swapping to sexual sadomasochism. This really isn’t a play for children…[8]

If you know your Beatles’ history well enough, you might be reminded of how the band’s giggly, innocent appearance often concealed private bacchanalian affairs. In both Shakespeare’s play and The Beatles’ story, subversive elements occasionally bob up to the surface, however hard some try to submerge them.

It would appear that the connection made between The Beatles and Shakespeare at the outset of Around The Beatles struck a chord with the British public, including with the band themselves. In 1965, Peter Sellers would make an appearance on The Music of Lennon and McCartney (another Beatle-themed television special) in order to recite the lyrics to ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ in the style of Laurence Olivier’s Richard III. At the time, Olivier’s film versions represented the high-water mark of Shakespearean performance in the British collective consciousness, something which is also evident in Around The Beatles: the special begins with a trumpet fanfare and flag raising ceremony which is almost identical to that at the outset of Olivier’s own film of Henry V. Sellers’ performance of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ is tonally comparable to The Beatles’ own attempt at ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’, too, both celebrating and gently mocking its source material.

youtube

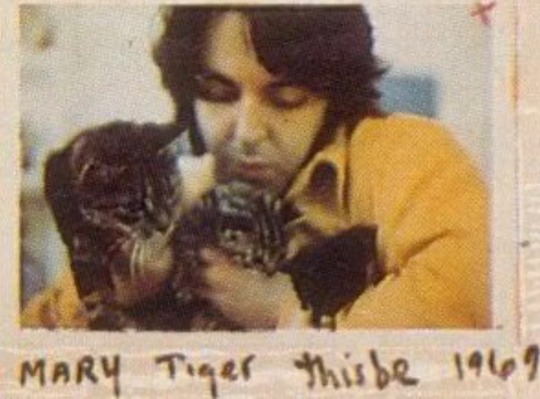

Paul may have recalled the Shakespearean dialogue he was required to recite in Around The Beatles a few years later, when choosing the name ‘Thisbe’ for a pet cat. He was certainly aiming for the grandeur of Shakespearean verse when composing ‘The End’ for Abbey Road. Hunter Davis notes in The Beatles’ Lyrics that the song’s final couplet is ‘almost Shakespearean’[9] in effect. He attributes this to the lines’ familiarity, but it is worth pointing out that Paul's lyrics achieve a Shakespearean effect partly because they are metrically identical to the verse form of Shakespeare’s epilogues: both employ an iambic tetrameter that is less expansive and more formal than their authors' common rhythms, which in Shakespeare's case is the 'blank verse' of iambic pentamer. Changing the meter for an epilogue allowed Shakespeare to place the tidy symmetry of his play's resolution within a pleasing metrical frame, just as the final words of ‘The End’ draw the threads of Abbey Road's song suite together and tie them in a satisfying bow that also contains a parting message of hope and comfort. When set next to each other, the similarities between Paul's and Shakespeare's lines are evident, and they serve as a better end to this article than its author can devise for himself:

Give me your hands if we be friends And Robin shall restore amends. And in the end the love you take Is equal to the love you make.

[1] The Beatles. ‘Around the Beatles Rehearsal Tape’. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FF7845r9WIo. Accessed 11.05.2020.

[2] Marjorie Garber. Shakespeare After All (2004). New York: Anchor Books, p.233.

[3] Stephen Greenblatt (Ed.). The Norton Shakespeare (1997). New York: W.W. Norton and Company, p. 807.

[4] Garber (2004), p. 213.

[5] The Beatles. ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream Excerpt’. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Owin8pcoyBQ. Accessed 11.05.2020.

[6] ‘Around the Beatles Rehearsal Tape’.

[7] Albert Maysles and David Maysles (Dir.). What’s Happening! The Beatles in the USA (1964). Maysles Film.

[8] Emma Smith. This is Shakespeare: How to Read the World’s Greatest Playwright (2019). London: Pelican Books, p. 85.

[9] Hunter Davies. The Beatles’ Lyrics (2014). London: Weidenfeld &Nicolson, p.378.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lessons Learned From Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

III. How to experience spontaneous, self-directed learning

Frankly, I don’t believe that Ferris, Cameron and Sloane would have spent their ‘day off’ better in school. Consider everything they pack into it: they ascend to the top of Willis Tower and observe the ant-like movements of workers 1400 feet below; they stare at the frenzied floor of the stock exchange and learn the sign-language of its traders; they take in a baseball game at Wrigley Field at the exact moment they should be enduring a gym lesson. Far from blowing learning off, Ferris’s rich schedule of activities achieves anything you could want for an educational field trip. The point is well made in a scene filmed inside the Art Institute of Chicago in which Ferris, Cameron and Sloane hold hands with a group of much younger children who are there with their teacher – everything they do mirrors the curriculum being delivered to their campus-bound classmates, the difference being how much more engaged they are.

youtube

John Hughes offers a comparable opportunity to the film’s audience. During the same gallery sequence, lengthy shots of masterpieces by Edward Hopper, Amedeo Modigliani, Jackson Pollock and Pablo Picasso fill the screen to an instrumental version of the Smiths’ song ‘Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want’. There is no clear motive to this montage: it doesn’t advance the film’s plot or match the frenetic pace of its comic hijinks; the art is celebrated for its own sake. Perhaps Hughes is doing for Ferris Bueller’s Day Off what galleries do for cities the world over, providing a respite to the bustle and purpose of everything else. In narrative terms, the scene is a prime example of what Timothy Morton means when he says that a ‘middle’ (development) is characterized by a slow, meditative pace and a feeling of absorption. In educational terms, the scene supports a claim for the value of the unplanned (much of it was improvised) or the apparently irrelevant. It can be frustrating for English or Arts teachers to vindicate their content in ‘lessons planned for … audit and accountability’, sacrificing ‘the unfinalisable struggle for meaning’ at the mendacious altar of ‘the easily-measurable’. Art, music and literature are illustrative of the ways in which meaning can be a slippery, mercurial thing; when they appear in an educational context they can also force a distinction between usefulness and value, reminding us that many of the things we place the highest value on are, from a utilitarian perspective, useless: chocolate, wine, sunsets, love. Hughes’s Art Institute sequence invites us to consider the flaws of an education system so staid and inflexible that it requires a ‘day off’ for students to reckon with something powerful enough to influence their perception of themselves and the world around them.

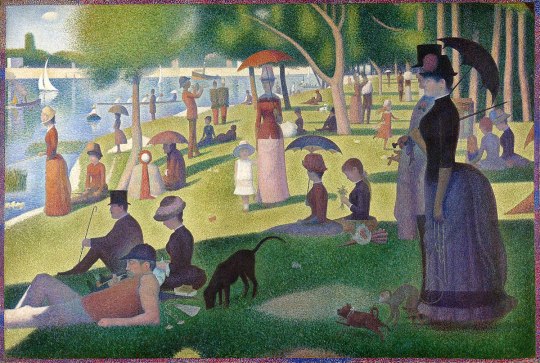

It is just such a reckoning that occurs when Cameron stands alone before Georges Seurat’s pointillist work, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. The painting depicts a group of well-to-do people promenading by the banks of the river Seine in the late 19th century, the men in top hats and the women in bustle-heavy dresses. Everyone in the painting seems together yet somehow alone, and a small girl dressed in white stares at the viewer from the centre of the canvas. Cameron fixates on this little girl – she is the only figure in the painting who makes a connection to the world outside its frame, and so the raw perceptive powers of childhood are contrasted against the dulling superficiality of adulthood. A teenager hovering between these two states of being, Cameron’s wrapped expression suggests that he is young enough to identify with the child but old enough to fear the looming demands of adult life. The film cross-cuts between increasingly close shots of his face and that of the girl, who on closer inspection appears to be wailing in distress. Eventually, Cameron’s eyes and the specks of paint on Seurat’s canvas appear in such extreme close-up that they cannot be resolved as themselves – they become abstract details of shape and colour.

It’s an ambiguous but quite moving sequence of film, especially when set inside of a breezy, feel-good comedy. If there’s a point, it may be that Cameron sees his own anxieties reflected in the girl’s anguished face and either he or the audience (or both) are made aware that overwhelming pain can obliterate identity. Hughes alludes to this in an audio commentary recorded for the film’s DVD release:

The closer he looks at the child, the less he sees with this style of painting. The more he looks at it there’s nothing there. He fears that the more you look at him there isn’t anything to see. There’s nothing there. That’s him.

Erik Erikson’s seminal research into identity formation considers that emerging adults experience a dynamic interplay between identity synthesis and identity confusion: while most of us use the process of ‘trying out’ possibilities to determine an internally consistent sense of self, some experience an arrested development in which a fragmented or piecemeal selfhood does not support decision making. On this basis, we might consider Ferris’s play-acting to be an example of normative behaviour leading to identify formation. Cameron, on the other hand, appears to be enduring an atypical crisis: believing himself to be dying from an incurable disease, immobile with anxiety at the wheel of his car, staring in horrified recognition at the deconstructed face of Suerat’s child, he could be said to exemplify what James Marcia calls ‘identity diffusion’: he does not enjoy exploring options in the way that Ferris does, nor does he make a commitment to any of the possibilities lain before him. When an incredulous Ferris asks him to acknowledge all that he’s seen and done on his ‘day off’, Cameron’s laconic response is, ‘Nothing good’.

Perhaps we should resist the temptation to psychoanalyse a fictional character as though he were possessed of a ‘real’ inner life. Cameron has more depth than Ed Rooney, but he’s not Hamlet. Ferris is the character you want to be, but Cameron is who you think you are (or fear you might be). Because you identify with him, there’s a temptation to project your psychology onto him. This might lead to the sobering realisation that you share some of his issues, but it’s worth remembering that Cameron is also a more perceptive individual than his famous friend. It is his depth and sensitivity that awe him when confronted by Seurat’s painting. The moment is almost epiphanic: what could be more absorbing than seeing yourself staring back at you from a hundred-year-old work of art? Ferris and Sloane enjoy their ‘day off’, but Cameron has a life-altering encounter, despite his claim of not having seen anything good. At the end of the film (and in a revealing act of growth) he resolves to confront his authoritarian father. Eleanor Harvey, senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, considers there to be a direct link between his experience of the painting and the way the arc of his character resolves: ‘That encounter with the painting … gives [Cameron] courage to understand that he can stand up for himself’. Not a bad lesson to have learned on your day off.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lessons Learned From Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

II. How to let jealousy obscure your judgment

youtube

A frequently-quoted line from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off articulates the way its hero perches atop his school’s social tree yet still enjoys a relationship with each of its sub-cultural branches: ‘He’s very popular … the sportos, the motorheads, geeks, sluts, bloods, wastoids, dweebies, dickheads – they all adore him’. It may be worth pausing to consider how valued this quality is in the American ethos. Ferris brings people together, de-alienating estranged or antagonistic cliques with a charm and optimism that never fails to win him supporters. He’s an embryonic politician. It’s fair to say that the only character in the film who doesn’t adore him is the school’s principal, Ed Rooney. Rooney lacks all of Ferris’s winning qualities: he alienates, bemuses or angers representatives of every section of American life. He’s forever beset by hindrances and his brittle authority is constantly eroding. Like Basil Fawlty, he’s either smug and superior (when looking down on students) or fawning and obsequious (when looking up to rich and powerful parents).

Director John Hughes described Rooney as a man who covets a throne, but who is forced to assume a lowly chair. This is why he’s driven by a jealous desire to destroy Ferris: it maddens him to see a student possessed of everything he considers to be rightfully his. Rooney’s jealousy also explains how he can be so blind to the content of Ferris’s character. Arguing with his secretary, he claims that ‘what is so dangerous about … Ferris Bueller is he gives good kids bad ideas … he jeapordises my ability to effectively govern this student body … [I have to] show these kids that the example he sets is a first-class ticket to nowhere’. Rooney is right to suggest that Ferris undermines his authority (as much as he obfuscates the point in management speak), but everything else he claims could not be further from the truth. Ferris’s ‘day off’ has nothing to do with tempting studious classmates into trouble; it’s a means of forcing his fragile and troubled best friend into confronting his demons. Imminently bound for different universities, the clock is ticking for these childhood buddies, and Ferris’s decision to focus one final adventure on Cameron as an antidote to his anxiety is both loyal and touching. Ferris lends his oldest friend a lust for life when it’s needed most.

Rooney bristles at the challenge Ferris’s youth poses to his own adulthood, but he should look more closely at how the pose is struck: in one of the film’s early scenes, Ferris disguises himself as his girlfriend Sloane’s father and (with Cameron’s help) persuades Rooney to let her off classes for the rest of the day. In a later scene, Ferris pretends to be Abe Froman (‘the sausage king of Chicago’) and talks his way to a table at a fully-booked restaurant. Apart from being expert demonstrations of the arts of persuasion, both scenes dramatise the incipient adulthood that Ferris knows he must step into. He’s playing with aspects of identity in exactly the way that James Paul Gee considered essential to adolescent learning and development:

[adolescents] must see and make connections between [a] new identity and other identities they have already formed … Such a commitment requires that they are willing to see themselves in terms of a new identity, that is, to see themselves as the kind of person [Gee’s italics] who can learn, use and value the new … domain’.

James Marcia identified this in terms of a ‘moratorium’ stage of identity formation (‘the process of exploration’), and Molly Davis has made a similar argument, defending ‘the [roles that] students experiment with and “try on” for size’. This might be achieved by donning the costume of laboratory coat and safety goggles in Chemistry lessons, but Ferris does it by assuming the face of white yuppie privilege. It’s authentic, experiential learning that puts his considerable intelligence and guile into practice. Far from buying himself a ticket to nowhere, the film depicts Ferris easing himself into the red Porsche of success. Rooney may or may not sense this, but he certainly doesn’t acknowledge it. The clichés he mouths about ‘bad examples’ and ‘governing the student body’ blinker him to reality and fix him as a two-dimensional authority figure.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lessons Learned From Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

I. How to Deliver a Bad Lecture ‘Bueller? Bueller? Bueller?’ repeats Ben Stein’s Economics teacher, his brow raised expectantly and his eyes scanning rows of pimply students for a response. The camera cuts to a vacant chair in which the absent Ferris Bueller should be sitting. It’s clear that the teacher has no idea who ‘Bueller’ is – he’d probably go on calling the name out forever like some malfunctioning automaton, but a perky, obliging girl cuts him off and explains that Ferris is sick. He thanks her in a way that suggests concealed impatience at the interruption, and then he launches into an interminable lecture about economic policy in the era of the Great Depression. His tone is arid and affectless, an unmodulated drone that transforms the classroom into a purgatory of boredom: the students’ glazed eyes and slack jaws suggest that they have been lobotomised (one has fallen asleep, a puddle of drool gathering on his desk). The teacher has probably given this lecture often enough that he’s on auto-pilot, his mind entirely elsewhere (everyone will likely carry on with their lives as though none of this ever happened). What makes him a bad teacher would appear to be obvious: he doesn’t have (or want) any kind of relationship with his students, he’s uninterested in their learning, and his response to any provocation is the same cold indifference – he is entirely ineffective. To label him a ‘bad’ teacher might misrepresent the student experience, however. Indeed, he is an object lesson in what Oscar Wilde meant when he claimed that it was ‘absurd to divide people into good and bad. People are either charming or tedious’. Were they to respond to a multiple-choice question asking them to identify the most apt description of their teacher’s lecture, I expect that most students would select ‘A. Boring’ over ‘B. Didactic’, ‘C. Ineffective’ or ‘D. Miseducative’, and they would probably be right.

Instead of applying a vague value judgement like ‘bad’, it may be more profitable to compare the lecture to a celebrated pedagogical model – John Hattie’s ‘seven steps of direct instruction’, for instance. Anything from within Hattie’s theory of Visible Learning may seem an odd frame to place around a conceptual, meditative article such as this: his meta-analyses are sometimes considered the apogee of educational research employing abstract data to valorise ‘what works’ at a macro level, flattening out complexity and contextual significance. This is too simple to be true, however – teacher autonomy remains a salient point in Hattie’s landscape of efficacy, and one of his more recent works makes the case that all failures in education are essentially failures of empathy (that of teacher, student or both). Apart from anything else, Hattie’s ‘seven steps’ remain one of the most authoritative guides to instructional pedagogy, and so they might at least clarify missed opportunities and illustrate how we can avoid making similar mistakes to those of Stein’s Economics teacher.

Hattie would probably consider Stein’s teacher to have cut across or stumbled over all seven of his steps, beginning with a failure to clarify learning intention(s): it’s unclear what, if anything, students should take away from his sermon about ‘the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act’, as it seems to be going everywhere and nowhere at once. Ultimately, this essay is critical of a dogmatic attitude to pre-determined outcomes in teaching, but Hattie does have a point when he writes that teachers should have some idea about what a lesson’s ‘success criteria’ are and should be able to hold students accountable for them. What we have in this early scene from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is a teacher who appears to have given up setting goals for himself, let alone those in his charge. There’s certainly no ‘hook’ to grab and hold students’ attention (Ibid., 206), nor is there any guided or independent practice of what has been taught to absorb students in active learning. There is nothing for these students to do: they are as passive and immobile as it is possible to be – they don’t even blink. The teacher makes a feeble attempt to phrase elements of his lecture as questions (‘Anyone? Anyone?’) but no one takes up the challenge and so he answers his own questions moments after asking them. There’s no genuine attempt to engage students in dialogue, no feedback given and ‘no actions or statements … that are designed to bring a lesson presentation to an appropriate [end]’. There is only the teacher’s bland stream of consciousness.

It’s tempting to think of the scene as evidence of why teaching should be student-focused and inquiry-driven: there’s nothing in the lecture to explore, uncover or connect to, and so students disengage their brains until the end-of-lesson bell stirs them enough to leave the room. Before we consign ‘sage on the stage’ didacticism to the ash heap of history, however, perhaps we should consider whether exchanging it for ‘guide on the side’ facilitation creates a false dichotomy between different elements of teaching that each have their value. Most teachers would agree that instructional phases allow a teacher to assume the role of expert model and afford students the opportunity to learn how to ‘do’ by watching those who ‘can’. Brian Moon argues that an absence of faith in instruction and a total investment in ‘discovery learning’ can leave students ‘trapped within their own limited social experience’, even in a haven of self-actualisation like English. Hattie identifies a surprisingly large effect size of 0.6 for ‘direct instruction’ in comparison to 0.4 for ‘inquiry-based teaching’. It’s true that Hattie’s understanding of direct instruction encompasses much more than listless, meandering lectures, but his meta-analysis supports the case for better instruction, not the total absence of it.

When asked to recall a moment of classroom inspiration or a favourite teacher, it’s interesting how often people give examples of direct instruction. Jerome Bruner (the educational psychologist) recalls his high school science teacher ‘inviting me to extend my world of wonder to encompass hers. She was not just informing me. She was, rather, negotiating the world of wonder … [as] a human event, not a transmission device’ (Bruner 1986, 126). To me, that sounds like something Hattie would call an ‘empathy success’. Similarly, the Australian actor John Bell identifies the spark of his career igniting over a sequence of teacher-focused lessons on A Midsummer Night’s Dream: ‘[the teacher] performed the whole play – all the characters and voices … it was wonderfully entertaining’. In both cases, teachers romanticised their discipline by modelling the beguiled and curious attitudes they wanted students to assume; they recognised that enthusiasm is infectious and that, for good or ill, a teacher functions as a symbol of their subject. Stein’s fictional Economics teacher provides a third – negative – example of this maxim: if a teacher can’t muster any enthusiasm, what hope have students got?

In a fascinating article on the importance of narrative in instructional pedagogies, Catherine Heinemeyer and Sally Durkham argue that our ‘progressive era’s democratic focus on the [student’s] voice, experiential learning, play and freedom … [discourages] many teachers from embracing the apparently authoritarian role of storyteller’ and that a concomitant culture of ‘lessons planned for pace and demonstrable progress in learning skills … measurement, audit and accountability’ exacerbates a misguided assumption that all forms of direct instruction render students passive and subservient. Brenton Doecke agrees, lamenting the conditions of a schooling environment in which ‘Everything is directed towards achieving pre-conceived outcomes, rather than allowing teachers to seize those unanticipated moments with their students where they can throw themselves into imagination and play’. Ann Craft considers a problematic tension to exist between an emphasis on creativity and a powerful but narrow set of drivers measuring achievement; she also recognises the challenge this tension poses to the legitimacy of what she calls ‘performance pedagogies’. Heinemeyer, Durkham, Doecke and Craft all agree that some forms of direct instruction can be as effective as they are memorable, stimulating the imagination to incorporate new elements into existing behaviours and modes of thinking.

As much as he needs to consider his students’ learning, then, Stein’s Economics teacher also needs to enliven his teaching. How should we advise him to do this? Where to begin? Perhaps we should try to avoid alienating him with en vogue theory or ‘silver bullet’ technology – something tells me he wouldn’t be receptive to either. Instead, we might suggest a series of baby steps in the direction of something more familiar. Drawing from Heinemeyer and Durkham’s research, we might emphasise the importance of narrative form to direction instruction in teaching. Aristotle considered that narrative has a beginning, a middle and an end, a deceptively complex observation that the philosopher Timothy Morton amplified as aperture (an open, questioning uncertainty), development (a deeper, more assured experience of absorption) and closure (a reorientation to the world outside of the text). Good films, novels and plays share these structural elements, but so do good lessons – perhaps Stein’s teacher could draw inspiration from this. His lecture could certainly benefit from what Hattie calls a ‘hook’ on which to bait students’ engagement (a beginning), and there’s something in his stated concept of ‘voodoo economics’ that could have started things off with a bang (a video clip of a voodoo ceremony combined with the question, ‘What has this got to do with our President’s economic policy?’). A means of absorbing students in something participatory (i.e., a ‘middle’) could have drawn inspiration from Bueller’s presumed illness: in a subsequent scene, a fellow student is collecting donations to buy him a new kidney, and so I have no doubt that a senior-level Economics class would have collaborated on ways to maximise funds raised if their teacher had suggested it. If this is too much to ask at a moment’s notice, then perhaps the various threads of his lecture could at least have been tied together in an ending that contextualises the reality of supply-side economics: what will the effect of economic depression be on the cost of the boy’s medical treatment? What about the effect on the school they’re in? One of the reasons why the lecture is so boring is that Stein’s teacher doesn’t have the imagination to seize on what Doecke calls ‘those unanticipated moments’: his diatribe is mired in abstraction. A solid narrative would provide much-needed structure, but it would also encourage a more imaginative approach and serve to ground the lecture’s tariff acts in something concrete and relatable. It might also encourage the teacher to remember who his students are, alleviating those uninspired moments in which he monotonously repeats their names.

youtube

0 notes

Text

Here, There and Everywhere - but when?

In the final episode of McCartney 3, 2, 1, the titular composer recalls the rare seal of John Lennon’s approval: ‘John liked [‘Here, There and Everywhere’], and John was not one to praise … After we made this record, we were going to film in Austria (for the film, Help!) and me and John [sic] shared a ski chalet, and we were taking our boots off and we were playing the album. I remember him saying, “Oh, I like this one.” And, you know what, that was, like, enough … that was, like, great praise coming from John.’[1] In their responses to McCartney 3, 2, 1 on podcasts and social media platforms, commentators were quick to point out that ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ was recorded in June and released in August of 1966 (on Revolver), while the skiing scenes for Help! were filmed in Austria in March of 1965, more than a year earlier. The commentators’ (reasonable) assumption was that McCartney’s memory was faulty: Lennon must have been referring to a different song or his praise was bestowed at a different location and a different time.

A curiosity of the anecdote, however, is that McCartney has told it several times, in variations dating back at least as far as 1984 – it clearly means a lot to him. In his semi-official book, The Beatles Lyrics (2014), Hunter Davies legitimises a version of the story in which John and Paul didn’t play the completed Revolver, but rather ‘a cassette of all their recent songs and when it came to “Here, There and Everywhere”, John said, “I probably like that better than any of my songs on that tape.”’[2] Davies is likely to have recalled McCartney’s 1984 Playboy interview, as it is this interview in which McCartney first mentions the cassette tape (the detail about removing skiing boots in an Austrian chalet remains):

I remember one time when we were making Help! in Austria. We’d been out skiing all day for the film and so we were all tired. I usually shared a room with George. But on this particular occasion, I was in with John. We were taking our huge skiing boots off and getting ready for the evening and stuff, and we had one of our cassettes. It was one of the albums, probably Revolver or Rubber Soul – I’m a bit hazy about which one. It may have been the one that had my song ‘Here, There and Everywhere’. There were three of my songs and three of John’s songs on the side we were listening to. And for the first time ever, he just tossed it off, without saying anything definite, “Oh, I probably like your songs better than mine.” And that was it! That was the height of praise I ever got off him. Mumbles, “I probably like your songs better than mine.” Whoops! There was no one looking, so he could say it.[3]

It is interesting that the further back in time the anecdote is delivered (and so closer to the events it describes), the less certain its details become. In 1984 (a comparatively early telling), McCartney admits to being ‘a bit hazy’ about which of the band’s albums was most recent and confesses that ‘it may [my italics] have been the one that had … ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ on it. It is possible, then, that latter versions of the anecdote created a false association between the song and a separate instance of Lennon’s (grudging) approval in McCartney’s mind, combining authentic but unrelated particulars in the way that repeated tellings of a tale sometimes do.

The significance of Lennon’s praise and McCartney’s repeated emphasis on its winter setting encourage closer examination. It may be profitable to consider McCartney’s claim in light of other statements he has made about ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ – these might reveal how possible (or plausible) the alpine anecdote is. In Many Years From Now, McCartney recalls the genesis of ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ this way:

I sat out by the pool [of Kenwood, Lennon’s Surry home] on one of the sun chairs with my guitar and started strumming in E, and soon had a few chords, and I think by the time he’d woken up, I had pretty much written the song, so we took it indoors and finished it up.[4]

Miles identifies the occasion as ‘a nice June day’,[5] as does Steve Turner in Beatles ’66: The Revolutionary Year.[6] A warm month like June would make sense if Paul sat outside to compose the song while waiting for a sleepy Lennon to stir himself. If the song had been composed early enough to have existed on a ‘cassette’ in March of 1965, though, it could not have been in June of the previous year, as Lennon did not purchase ‘Kenwood’ until 15 July 1964 (the pool was installed as part of renovations made to the property after the purchase but prior to Lennon’s residence from the end of July).

Perhaps the month is wrong but the summer of 1964 remains a possibility. Mark Lewisohn places the Beatles in England from 1 July to 18 August 1964, then touring the United States of America until 21 September (by which time a poolside morning setting for the song’s composition may be too cold to be plausible).[7] There are, then, around 17 days of 1964’s August in which McCartney could conceivably have driven to ‘Kenwood’ and composed ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ while enjoying the last of the summer warmth. If he did so, however, we must admit that Lennon & McCartney chose to ‘sit on’ a finished song for nearly two years before recording it. McCartney has been known to hold back strong material for what he considers to be the right time, but this creative practice does not appear to have developed until a little later in his career; it was more common (and necessary) for The Beatles to write to order and to be keen to record and release material they knew to be strong. A cool decision to ignore ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ for two years is hard to parse, especially when you consider that the interim covers the making of Rubber Soul (an album for which the band were so hard up for material they nearly included the plodding ’12 Bar Original’).

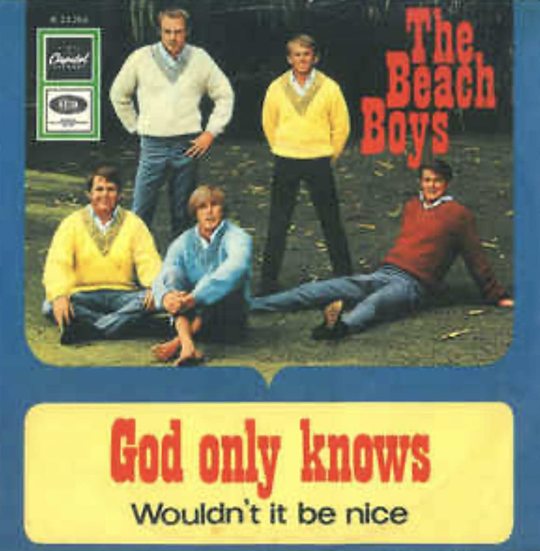

When you consider other evidence related to ‘Here, There and Everywhere’, the song’s composition prior to March of 1965 seems less likely still. When discussing the influence of The Beach Boys on The Beatles, Robert Rodriguez identifies McCartney as having ‘stated many times through the years that Pet Sounds’ “God Only Knows” … influenced him when composing and arranging “Here, There and Everywhere”’.[8] ‘God Only Knows’ was recorded between March and April of 1966 and released on Pet Sounds in May of that year, more than a year after the filming of Help! It is also the case that McCartney wrote and revised the lyrics to ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ on the reverse of a typed document outlining ‘BEATLE PLANS FOR NINETEEN SIXTY-SIX’, one that refers to both ‘Paperback Writer’ and ‘Rain’ (the band’s non-album single for 1966) as having been written and recorded. It is possible that McCartney refined the lyrics on the document in preparation for recording the song (rather than when composing it), but the fact remains that the sole primary source document related to ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ dates elements of the song’s composition to 1966. As Barry Miles notes, the document’s three-month schedule of concerts spanning Germany, Japan, Manila and the United States may have inspired the song’s title on the basis that The Beatles would soon find themselves travelling here, there and everywhere.[9]

At the risk of moving away from analysis and towards speculation, it may also be worth considering why McCartney has become increasingly convinced that that his former song-writing partner singled ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ out for praise at an alpine chalet over a year before it was recorded. Perhaps it is related to the fact that in March of 1966 (immediately before the making of Revolver), McCartney enjoyed another skiing holiday, one in which he wrote the song ‘For No One’ in a different alpine chalet: ‘I was in Switzerland on my first skiing holiday. I’d done a bit of skiing in Help! and quite liked it, so I went back and ended up in a little bathroom in a Swiss chalet writing “For No One”’.[10] John Lennon was not present, and the song in question is not the same, but it is comparable to ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ in that it was written and recorded for the same album and it stands as another of McCartney’s exquisitely-crafted baroque-pop ballads. It is also a song that Lennon would single out for praise: ‘One of my favourites of his. A nice piece of work.’[11] To call the song ‘a nice piece of work’ is to concede a measure of laconic, guarded respect comparable to the admission, ‘Oh, I like this one.’ If the setting for the song’s composition was near-identical to that of the filming of Help!, the similarity may have been enough for McCartney to elide the two experiences, intermingling memories of a heady period of life crammed with incident.

[1] Zachary Hienzerling (Dir.) (2021). McCartney 3, 2, 1. Hulu/Disney+

[2] Hunter Davies (2014). The Beatles Lyrics: the Unseen Story Behind Their Music. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p. 168.

[3] Retrieved from https://www.the-paulmccartney-project.com/interview/the-1984-playboy-interview/

[4] Barry Miles (1997). Many Years From Now. London: Secker & Warburg, pp. 285-286.

[5] Ibid., p. 285.

[6] Steve Turner (2016). Beatles ’66: The Revolutionary Year. New York: HarperCollins, p. 204.

[7] Mark Lewisohn (1987). The Beatles Day By Day: A Chronology 1962-1989. New York: Harmony Books, pp. 48-53.

[8] Robert Rodriguez (2012). Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock ‘ n’ Roll. Milwaukee: Backbeat Books, p. 78.

[9] Miles (2014), pp. 170-171.

[10] Retrieved from https://www.the-paulmccartney-project.com/song/for-no-one/

[11] Retrieved from https://www.beatlesbible.com/songs/for-no-one/

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dave the teacher, or the short story as a kind-of lesson.

III.

A sub-theme of this post has been the extent to which Wallace’s teaching was influenced by his writing (or at least his authorial persona). You may have noticed fleeting glances in the direction of “Forever Overhead”, Infinite Jest and This is Water. With these in mind, it might be profitable for the final phase of our inquiry to consider how much Wallace’s writing was informed by his teaching. Again, the question is a large one that cannot be addressed comprehensively here. If we hang the question on something discrete, however, we may be afforded a window that looks out over the answer’s wider terrain. Consider the short story, “Think”, from Brief Interviews with Hideous Men (1999). A two-page piece of ‘micro-fiction’, the story describes a rather tawdry attempt at adultery that takes an unexpected turn as one of the participants experiences something like religious ecstasy. I choose this example partly because the very title – “Think” – seems so teacherly in light of this discussion. It’s single word might appear intriguing to the casual reader, an oblique semiotic clue hinting at the larger puzzle of the story, but if we clothe Wallace in his academic gown and remember his reputation as a ‘pedagogical hard-ass’, “Think” seems more like an interrogative command, one that your own teachers may have punctuated silences with after a question hung in the air for too long (“What’s one of the themes of this story? … C’mon people, THINK!”). The injunction to think, then, has the effect of many of Wallace’s course syllabi: like the phrases “don’t be late … your deadlines are obligations to twelve other adults” and “work that appears sloppy or semiliterate will not be accepted for credit”, the agenda behind the text is to warn the complacent student (or reader) that this is going to be hard work: you’re going to sweat over this and the easy validation and satisfaction you’re hoping for will not be given.

youtube

“Think” raises all manner of knotty questions designed to make the reader’s forehead pucker as intensely as its protagonist’s does just before his moment of revelation. Consider, for instance, the oblique quality of the narrative’s free, indirect discourse:

She could try, for just a moment, to imagine what is happening in his head. A bathroom scale just barely peeking out from below the foot of the bed, beneath the gauzy hem of the comforter. Even for an instant, to try putting herself in his place.

Those first and last sentences appear to be diegesis: words spoken by a narrator who may or may not be Wallace offering the reader their opinion as to how the story might resolve, (one that implies a moral judgement of the female character’s empathetic failings). Sandwiched between those two sentences, however, is a third describing a curious feature of the hotel room without context (or apparent relevance). It’s tempting to think of it as a moment of mimesis interrupting the third-person diegesis: our male protagonist’s mind, in other words, noticing a bathroom scale in an incongruous setting. The point might be that even in moments of ecstasy, the mind can still be arrested by banal detail (what’s ‘happening’ in this guy’s head, maybe, is nothing special). Somehow, though, I don’t think that’s the point. At least, it’s not as simple as that. Because there’s no character attribution to the sentence about the scale peeking out from below the bed, its syntax implies that this is still our narrator speaking, alerting the reader to surface features of the setting right at the story’s emotional climax. Why? Is the narrator bored with the story he’s telling? Are they more interested in hotel furnishings than middle-aged, middle-class, mid-Western lives? Of course, another possibility is that all three sentences are examples of the protagonist’s self permeating the narrator’s discourse, in which case it’s really been the protagonist thinking all along, silently willing his wife’s college roommate’s younger sister to exercise a little empathy here (not so fervently, though, that he doesn’t stop to notice the bathroom scale beneath the bed). It’s not the case that each of these possibilities establish radically different readings of the story, but they do obscure our understanding of how much its characters are thinking and how much its narrator is inferring on our behalf. Again, the point is to force us to consider these ambiguities and their knotty implications. Like the girl in the quoted passage, we’re being told to “try to imagine what is happening”; we’re being induced to think.

If we take Wallace at his word and begin thinking about the story, anyone interested in education is likely to hover over the narrator’s description of the girl’s smile as “media-taught”. Some may even spend a moment unpacking the compound adjective for the teaching and learning implications it carries. For one, it represents mimesis of a different kind: no longer Wallace’s ability to construct a simulacrum of someone’s inner life, but rather the way in which this girl’s response to seduction is learned through imitation. Aristotle considered that all learning was mimetic (an attempt to reproduce the knowledge and skills performed by expert models). Albert Bandura’s social constructivism is referred to in part II of this post, a comparatively new theory based on the same Aristotelian idea. Bandura regarded the young self as an acquisitive and protean thing that develops socially by assuming the characteristics of what it encounters. He is careful to point out that this process is more nuanced and complex than what we might call ‘mere imitation’; rather, it is a fundamental and complex means by which individuals observe, intuit, remember and re-produce patterns of thought, whole behavioural systems, motives, values and ideals. In the case of Wallace’s story, the girl’s physiology is an index and symptom of this process taking the form of role-play (though the script has been written by a glut of advertising and bad TV that fetishises adultery).

If you consider that this interpretive line is too harsh on the female character, it’s worth pointing out that the protagonist’s identity is also demonstrably mimetic: experiencing his revelatory moment, he kneels and prays. A cynical reader might say that he’s replacing the iconography of Victoria’s Secret with the iconography of the Catholic church. It is suggested that moments of ecstasy might sometimes contain elements of the banal; perhaps they can also contain cliché?