they/them, she/her. use what you want. I can't speak English. Nevertheless, I wrote in English because I hope that my interpretation will be implanted in your brain. You can use what I wrote without citing the source or anything like that. If it's not allowed, I'll post it in Korean, so there's no need to make a mistake.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

matt just fired half the remaining tumblr support staff lmao

46K notes

·

View notes

Text

turning seasons 🌸🌻🍁❄️

. .

start of new cycle of spring, time to finally posting the full sets!

27K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Eddas & Middle-earth: The Impact Norse Mythology had on Tolkien's Legendarium

Tolkien was deeply fascinated with mythology, and Norse mythology, in particular, played a major role in shaping Middle-earth and the wider Legendarium. While he drew from various mythological and polytheistic traditions, the influence of Norse religion and culture is especially strong and well-documented throughout his work. His academic interests reflected this, too. During the 1920s, he co-founded the "Viking Club" at the University of Leeds, where he and his colleagues explored Germanic languages and Norse literature in detail.

So let's jump into it!

It was a lot of fun to do this, as I got to use my degree. There are many more connections, but I did the main ones that I could get sources for or knew of through my studies. Now, some are just speculation and just out of my connections when reading the stories. If you want more, I really suggest taking a look at alvigunilla over on Instagram. For three of these, she was the source, but I dug a little deeper on the Tolkien side.

SKÖLL & HATI

The story of the Sun and Moon in Tolkien's "Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor" in The Silmarillion resembles the story of Sköll and Hati. In fact, for most polytheistic religions, there is some resemblance to a creation of day and night, the passage of time. But in the context of this post, we will stick with the Nordic rendition.

In Norse mythology, Sköll and Hati are two wolves who chase the Sun and Moon through the sky. Their pursuit explains the cycles of day and night. Eventually, in Ragnarök, they catch their prey, ending the world as it’s known (Sturluson, The Prose Edda).

Tolkien’s version is more elaborate, but there are parallels. After the destruction of the Two Trees, the Valar created the Sun from the last fruit of Laurelin and the Moon from the last flower of Telperion (The Silmarillion). These are not just lights, but vessels guided through the sky by spirits; Arien for the Sun and Tilion for the Moon. The Moon, led by Tilion, even wanders and behaves unpredictably, echoing the restless chase seen in Norse myth.

Moreover, Morgoth hates these new lights and sends dark spirits against them. The imagery of constant threat, something dark always pursuing light, is reminiscent of Sköll and Hati. In both traditions, light is not guaranteed it must be defended and keep moving.

While Tolkien doesn’t directly insert wolves chasing celestial bodies, the idea of the Sun and Moon as active forces under siege draws clear influence from myths like that of Sköll and Hati. Light is never still, never safe. It runs to stay ahead of the dark.

THE BERSERKERS

Another clear echo of Norse mythology in Tolkien’s work is the figure of Beorn, the skin-changer from The Hobbit. He’s a man who can turn into a solitary, fierce, and dangerous bear in battle. This mirrors the Norse concept of the berserkers, warriors who fought in a trance-like fury, often associated with bears or wolves. The word “berserker” itself likely comes from ber (bear) and serkr (shirt), meaning “bear-shirt,” a reference to warriors who wore bear pelts and channeled the animal’s ferocity (The Saga of the Volsungs).

Beorn is a more controlled version of this idea. While berserkers are known for their uncontrollable rage, Beorn retains his will and morality, using his power to protect rather than destroy randomly. However, raw energy, the primal strength tied to a bear’s nature, is very much in line with Norse tradition.

Tolkien wasn’t copying but reworking. He stripped away the chaos and darkness of the berserker myth and gave it shape and purpose in Beorn. Still, the roots are evident: a man who becomes a bear, whose rage and strength in battle seem almost supernatural, and who stands apart from regular men, just like the berserkers of old.

THE DRAUGR

The barrow-wights in Tolkien’s world can also be traced back to Norse myth, specifically the draugr, undead figures that haunt burial mounds, guarding treasure and tormenting the living.

In The Fellowship of the Ring, the hobbits are captured by a barrow-wight in the Barrow-downs, an eerie, fog-covered place filled with ancient tombs. The wight attempts to sacrifice them, surrounding them with cold, fear, and spells of darkness. It hoards ancient blades and jewelry, and its presence is one of malice and death.

The draugr of Norse sagas are much the same. They dwell in graves, often those of kings or warriors, and possess unnatural strength. They jealously guard their wealth and attack anyone who comes near. Like Tolkien’s wights, they’re more than just corpses; they have will, purpose, and power tied to the grave (The Poetic Edda; Lindow, Norse Mythology).

Tolkien borrowed that core idea but gave it a distinct feel. His wights serve a darker force. Much like we see in season two of the Rings of Power; Sauron supposedly awakens the wights to block Eregion in hopes he can get time to complete his task of getting his rings of power. But the mythic connection is clear: restless dead tied to burial mounds, hostile to the living, and bound to treasure and old oaths.

It’s another case where Tolkien didn’t lift the concept whole, he reshaped it to fit his world. But the bones are Norse. Quite literally.

FREFYR VS. SURTR

The showdown between Freyr and Surtr in Norse mythology has echoes in Tolkien’s battles between Gandalf and the Balrog in The Fellowship of the Ring, and Glorfindel and a Balrog in The Silmarillion. The core image is the same: light versus fire, a noble figure facing a monstrous being in a final, sacrificial confrontation.

In Ragnarök, Freyr, god of fertility and light, faces Surtr, the fire giant who brings about the world’s destruction. Freyr falls because he gave up his sword, leaving himself vulnerable. But the fight isn’t meaningless; it’s part of a cosmic balance, a necessary ending to make way for renewal (Sturluson, The Prose Edda).

Now compare that to Gandalf’s fight in Moria. The Balrog is an ancient fire-demon, a corrupted Maia like Gandalf himself. Their battle is brutal and elemental: shadow and flame against light and resolve. Gandalf wins but only through death. Like Freyr, he sacrifices himself to defeat the fire-bringer. And like Freyr’s role in the cycle of Ragnarök, Gandalf’s fall clears the way for the Fellowship to survive, and he later returns transformed more powerful, more vital to the world’s salvation.

Glorfindel’s earlier confrontation with a Balrog carries the same weight. In defense of others, he throws the demon down from a mountain and falls with it. His sacrifice buys time and hope. He, too, is later sent back by the Valar, reborn to serve again. He and Gandalf mirror Freyr in this way: luminous figures who fall in fire but whose loss isn’t the end; it’s a turning point (The Silmarillion; The Fellowship of the Ring).

Surtr, like the Balrog, isn’t just a brute. He represents destruction with purpose. The battle isn't just physical in each of these pairings, Freyr vs. Surtr, Gandalf vs. Balrog, and Glorfindel vs. Balrog. It’s symbolic: the old world giving way, the cost of light standing firm against fire.

HELGI & SIGRÚN

The story of Beren and Lúthien in Tolkien’s legendarium shares striking parallels with the Norse saga of Helgi Hundingsbane and Sigrún. At their core, both stories are about love that defies doom, romance wrapped in fate, war, and the supernatural.

In the Helgi sagas, Sigrún is a Valkyrie who falls in love with Helgi, a mortal hero. She defies her father’s wishes and vows to marry Helgi, even though he’s fated to die young. She fights alongside him, supports him through battles, and mourns him deeply after his death. Their love transcends the usual bounds of mortality and divine law, even continuing in spirit. Helgi is allowed to return from the dead briefly, and the two are reunited in his barrow for a night (Helgakviða Hundingsbana, The Poetic Edda).

Tolkien’s Beren and Lúthien follow a similar arc. Lúthien, a Maia-born elf, falls in love with Beren, a mortal man. Her father sets what should be an impossible task; retrieving a Silmaril from Morgoth. She defies authority, braves the realm of the enemy, and even enchants Morgoth himself. Like Sigrún, Lúthien isn’t passive; she’s powerful, active, and utterly devoted. After Beren dies, she chooses mortality to be with him in the end, trading eternal life for love.

Both stories are tragic and beautiful. Both center around women of supernatural origin choosing love over divine law. And in both, the union of mortal and immortal defies fate, if only for a time.

Tolkien knew these sagas. And while he transforms them into something uniquely his own, the fingerprints of stories like Helgi and Sigrún are their deep love, sacrifice, and the brief victory of life and light over doom.

In the end, we know that Tolkien and his wife Edith were the true defining inspirations for Beren and Lúthien. However, one could also say that, in his reading and love for mythology, Tolkien came across this story in the Eddas and subconsciously wrote aspects into Beren and Lúthien (Garth, Tolkien and the Great War; Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien).

THE ANDVARANAUT

Tolkien’s One Ring owes a clear thematic debt to the Andvaranaut, the cursed ring from Norse mythology. Both are golden, powerful, and utterly corrupt. And both bring ruin not because of what they do but because of what people do for them.

In the Volsunga Saga, Andvaranaut is a magic ring owned by the dwarf Andvari. When Loki steals it, Andvari curses it: whoever possesses it will meet destruction. The ring becomes part of a treasure hoard that poisons every hand it passes through greed, betrayal, and murder. It’s not just wealth; it’s doom wrapped in gold.

Tolkien flips the script slightly. The One Ring isn’t just cursed; it’s actively malevolent. It has a will tied to Sauron. But like Andvaranaut, it seduces its bearers and destroys them slowly. It ruins Gollum, corrupts Boromir, and tempts Galadriel. It turns friends into enemies and twists good intentions into disaster. And, like the Norse ring, it traces back to a dark, ancient origin; a forge, a theft, and a fall (Shippey, The Road to Middle-earth).

Tolkien denied that the Ring was directly inspired by Andvaranaut or Wagner’s adaptation of it, but the echoes are hard to ignore. Both rings are small but world-breaking. Both seem to offer power but instead bring obsession and decay. And in both stories, the ring isn’t just an object; it’s a curse in disguise.

Tolkien didn’t copy the Andvaranaut. He re-engineered it. He stripped it of divine politics and re-centered it around will, temptation, and power. But the core remains: the idea that some treasures are too dangerous to keep and too seductive to let go.

THE ÁLFAR

Tolkien’s Elves owe a lot to the Norse Álfar. Both are ancient, powerful, and closely tied to nature, light, and magic. But the Álfar are elusive figures in Norse myth, part divine, part ancestral spirit. Tolkien builds them into a full-blown civilization with languages, histories, and tragedy.

In the Prose Edda, Álfar are divided into Ljósálfar (light elves) and Dökkálfar (dark elves) (The Prose Edda). The light elves live in Álfheimr, a heavenly realm of beauty and light, while the dark elves are earthbound, shadowy, and more ambiguous. This split feels echoed in Tolkien’s Elves: the High Elves (Vanyar, Noldor) who lived in the light of the Two Trees in Valinor, and those who stayed in Middle-earth, like the Sindar or Silvan Elves, who are less radiant but still deeply tied to the world (McIlwaine, Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth).

Tolkien takes this a step further. His Elves are immortal, deeply sorrowful, and bear the memory of the world’s early light. They’re not just nature spirits or mythic figures; they’re fully realized peoples with internal divisions, politics, and grief. Still, the Norse DNA shows up in the way they’re connected to the land, their craftsmanship (especially in works like Eöl’s or Fëanor’s), and their uneasy relationship with Men.

Also, the way Elves fade in Tolkien’s world mirrors how the Álfar became more hidden in Norse and later Scandinavian folklore, eventually becoming the unseen folk, replaced by legends of hidden beings and fae. In Middle-earth, the Elves are already a people in decline. Their time is ending. The age of Men is coming. That melancholy matches the way Álfar shift from central figures in early myth to fading presences in the background of later tales.

Tolkien didn’t just borrow the idea of elves from Norse myth he expanded it. He gave them history, pain, and a deep sense of loss. But the roots go back to Álfheimr, to the light elves of myth who were never quite gods, never quite mortal, and never fully understood.

HUGR, ORLOG & WYRD

Tolkien’s legendarium, especially in works like The Silmarillion and The Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth, includes a deep metaphysical system. While Christian in its foundation, it shares notable parallels with Norse and Germanic spiritual ideas, particularly Orlog, Wyrd, and Hugr.

Fëar (souls) in Tolkien’s world are the immortal spirits of Elves and Men. The fëa drives identity, memory, will, and moral direction; it’s the spiritual core. This lines up closely with the Norse concept of hugr, which refers to the mind, will, or inner self. The hugr was not just thought, but intention and presence it was something that could affect the world, even project itself. The fëa, like the hugr, shapes action and fate. In Elves, whose fëar are bound to the world until its end, this spiritual presence can even influence matter and perception; hence their ability to create beauty or fall into ruin.

Then there's Orlog, the idea in Norse belief that each being carries a web of accumulated deeds and inherited strands of fate. It's layered over generations, and what ancestors have done echoes into your own life. That concept maps well to how Tolkien builds Elvish and Mannish destinies. For instance, the Doom of the Noldor isn’t just divine punishment; it’s Orlog-like. Their choices in Valinor, oaths, and Kinslayings carry forward into every generation, shaping their fate, even when some try to break free, like we see with Fëanor’s line.

Wyrd, often translated as "fate" or "becoming," is the unfolding of life shaped by action and character. It’s not a fixed destiny but a pattern that builds with every choice. Tolkien’s view of fate works much the same way. Characters aren’t locked into a path but move within larger frameworks, like the Music of the Ainur, which sets the theme but allows for improvisation. Frodo wasn’t fated to succeed, but his choices moved within a moral arc that shaped what was possible (Lindow, Norse Mythology; Tolkien, Morgoth’s Ring).

Together, hugr, orlog, and wyrd describe an interplay of spirit, accumulated deed, and unfolding fate. Tolkien’s fëar, the long memory of Elves, the weight of oaths, and the way choices echo across ages these are built from that same structure.

Tolkien didn’t import Norse metaphysics wholesale, but he clearly understood them. He reworked them into a moral world where spirit, action, and fate all matter, just as they did to the ancients who first spoke of wyrd and orlog under cold skies.

RAGNARÖK

Tolkien’s concept of Dagor Dagorath, the final battle foretold in his legendarium, shares clear similarities with Ragnarök, the Norse myth of the end of the world. Both are apocalyptic confrontations between forces of light and darkness, involving gods or godlike beings, and culminating in destruction followed by renewal.

In Ragnarök, the world is torn apart as gods and monsters clash: Odin is slain by Fenrir, Thor kills the World Serpent but dies from its poison, and Surtr sets the world ablaze. After the devastation, a new world rises from the sea, fresh, green, and ready for a new age (Sturluson, The Prose Edda).

Tolkien’s Dagor Dagorath ("The Battle of All Battles") is less detailed but follows a similar arc. It’s prophesied that Morgoth, the original dark power, will break the Doors of Night and return to the world. A final alliance of the Valar, Elves, and Men, led by Eärendil, Túrin, and others, will rise to confront him. Morgoth will be defeated once and for all, likely by Túrin, a mortal hero striking down a godlike evil. After the battle, the world is expected to be remade or healed, echoing the post-Ragnarök rebirth (The Shaping of Middle-earth; The Silmarillion appendices).

Tolkien reshaped Ragnarök’s grim fatalism into something more redemptive. While Norse myth ends in twilight and uncertainty; Dagor Dagorath holds out hope that evil can be defeated, and the world can be renewed.

SOURCES

Byock, Jesse, trans. The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

Larrington, Carolyne, trans. The Poetic Edda. Revised edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Lindow, John. Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Shippey, Tom. The Road to Middle-earth. Revised edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003.

Snorri Sturluson. The Prose Edda. Translated by Jesse L. Byock. London: Penguin Classics, 2005.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Silmarillion. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Fellowship of the Ring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1954.

Tolkien, J.R.R. Morgoth’s Ring: The Later Silmarillion, Part One. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Read The Silmarillion So You Don't Have To, Part 12

Previous part.

Chapter 24: Of the Voyage of Eärendil and the War of Wrath In which a mariner embarks on a legendary voyage, and Morgoth is finally defeated.

Eärendil was a mariner That tarried in Arvernien; he built a boat of timber felled in Nimbrethil to journey in. —Bilbo, The Fellowship of the Ring

Alright, everybody! It’s finally time for the Voyage of Eärendil! I’ve been excited for this one. A bit of background, so you understand the significance of this:

Eärendil is the oldest piece of Tolkien’s Middle-earth worldbuilding. He was inspired by a single line in an Old English poem, Crist 1:

Eala earendel, engla beorhtast, ofer middangeard monnum sended, ond soðfæsta sunnan leoma, torht ofer tunglas, þu tida gehwane of sylfum þe symle inlihtes! O Earendel, brightest of angels, over middle-earth sent to men, and a beam of the true sun, brighter than the stars, for all time you always illuminate yourself!

I think this poem identifies Earendel as the rising sun rather than as the evening star, but versions of this same character appear in other Germanic texts, in which he’s related to the evening star. He appears briefly in the Prose Edda under the name Aurvandil:

Wanting to please and reward Groa for her healing, he [Thor] told the story of his return from the north, and how he had waded across the river Elivagar, carrying Aurvandil southwards from Giant Land on his back in a basket. He recounted that one of Aurvandil’s toes had stuck out from the basket and had frozen. Thor broke it off and threw it up into the heavens as a token, making from it the star called Aurvandil’s Toe. (trans. Jesse L. Byock)

Aurvandil/Earendel might have been a Germanic god of the dawn or the planet Venus, similar to Eosphoros, who was reinterpreted as an angel after Christianization.

Tolkien took this idea of Earendel as the evening star, and just ran with it. His first poem about Eärendil is called “Éala Éarendel Engla Beorhtast,” and it describes Éarendel sailing east in a magic ship, chasing the rising sun. The title is the Old English line from Crist 1. Tolkien’s original poem bears some similarities to the “Song of Eärendil” that Bilbo sings in Fellowship. So, in a lot of ways, the story of Eärendil is Tolkien’s most direct tribute to medieval literature. It also pays tribute to the more general mythological motif of a hero on a sea voyage to the Otherworld. I really like how Tolkien took this obscure character mentioned in a few medieval stories, and made him a focal point of his own mythology.

Light of Eärendil by breath-art

With how big of a deal this story is, it’s kind of a shame that it’s so brief in The Silmarillion. But I’ll take what I can get.

Where our story picks back up, Eärendil becomes king of the Havens at the mouth of the Sirion after his parents’ departure. The Havens have become a sort of melting-pot of refugees from the sack of Gondolin, the sack of Doriath, and all the other destroyed kingdoms of Middle-earth. Eärendil marries one of these refugees, an Elf named Elwing. She’s the granddaughter of Beren and Lúthien. They have two half-elf sons, Elros and Elrond (yup, that one). They’re as happy as they can be under the circumstances, but Eärendil is afflicted with that sea-longing that his father had.

Eärendil decides to sail for Valinor, to convince the Valar to do something about Morgoth. Middle-earth is all but doomed at this point, now that all the great kingdoms are a pile of rubble, and desperate times call for desperate measures. Eärendil also hopes to find his parents, who sailed off into the sunset and never came back. With Círdan’s help, he builds a beautiful white ship made of birchwood, with silver sails and golden oars. The ship’s name is Vingilot, “foam-flower.”

When Eärendil sets sail, Elwing sits on the shore and cries, assuming she’ll never see her husband again. And I can hardly blame her. Dude straight-up abandoned his family!

Eärendil’s initial attempt at reaching Valinor does not go well. The sea is full of “shadows and enchantments,” and winds buffet the ship away from the western shore. Eärendil doesn’t find his parents, either. Feeling hopeless and missing his wife, he decides to turn the ship around.

Meanwhile, Maedhros hears that Elwing survived the Second Kinslaying at Doriath, and that she has her grandparents’ Silmaril. Feeling awful for his actions at Doriath, Maedhros decides not to go after the Silmaril this time. But oaths are magical, and you can’t just decide to ignore them. Maedhros and all his brothers are mentally tortured by the knowledge that Elwing has the Silmaril. The brothers begin by sending a strongly-worded letter, demanding that Elwing return it. The people of the Havens refuse to return it, because its magic is part of what’s keeping them safe.

So, what do you think happens? You think the Feanorians are just going to turn away this time? Hahaha nope. Instead we get the Third Kinslaying! It’s “the last and cruelest” of the conflicts caused by the Fëanorian Oath. It’s so brutal that some of the Fëanorians’ own people refuse to slaughter the helpless refugees, and are promptly killed for being traitors. At the end of the battle, only two Fëanorians, Maedhros and Maglor, are left standing. Elros and Elrond are kidnapped, and Elwing throws herself into the sea with the Silmaril.

Ulmo rescues her, turning her into a white bird, with the Silmaril shining on her breast. Elwing flies over the western sea, and finds her husband on his boat. She flies down out of the stormy clouds like a falling star. Eärendil sees the magical bird turn into his wife, and she sleeps in his arms for the first time in years.

Eärendil and Elwing by Kamehame

Eärendil is happy to see his wife again, but devastated to learn about the sack of the Havens and the kidnapping of his sons. Assuming that their sons have been killed, Eärendil and Elwing decide there’s nothing for them in Middle-earth, and try for Valinor again. This time, they have the Silmaril. Eärendil wears it on his forehead, and it shines out over the sea. Its light cuts through all darkness and illusions surrounding Valinor. So, Eärendil succeeds. His ship is the first one to reach Valinor in more than four thousand years.

The Teleri are astonished to see the shining ship sailing out of the West. I can picture it: the light of the Silmaril on the horizon like a mini-dawn, rising from the wrong direction.

Eärendil is the first mortal Man to ever set foot in Valinor. He recognizes the inherent danger in entering Fairyland, so he tells Elwing and his sailors to stay on the ship. This is the point of no return. Elwing won’t let her true love face such peril alone, so she leaps from the ship. Eärendil tells her to wait for him on the shore, and she does, reluctantly.

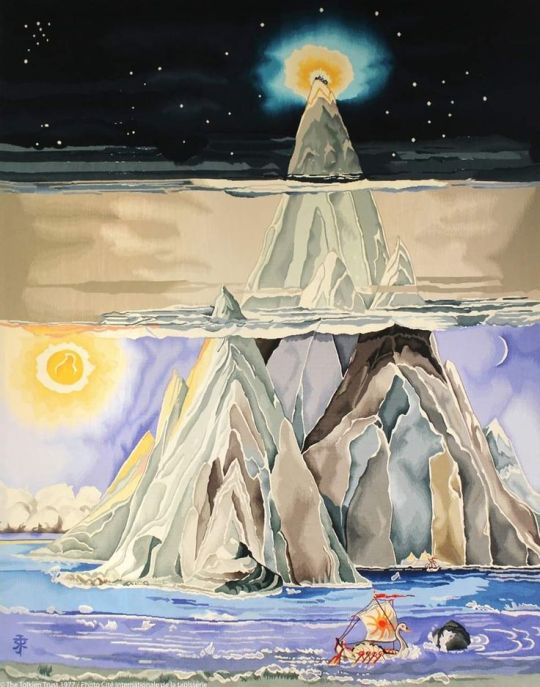

The Halls of Manwë on the Mountains of the World above Faerie by J.R.R. Tolkien

Valinor appears deserted. Eärendil enters the Noldor’s legendary city (where even the dust is made of diamonds), and finds it completely empty. Everyone is gathered in the Valar’s palace for a festival, just like when Morgoth and Ungoliant came to destroy the Trees. Eärendil calls out in as many languages as he knows, but no one answers him. Finally, he turns back towards the shore, thinking the mission was a waste, when suddenly, a voice calls from the top of the hill:

Hail, Eärendil, of mariners most renowned, the looked for that cometh at unawares, the longed for that cometh beyond hope! Hail Eärendil, bearer of light before the Sun and Moon! Splendour of the Children of the Earth, star in the darkness, jewel in the sunset, radiant in the morning!

Now, that’s one heck of a greeting! The person delivering it is Eönwë, a Maia, the herald of Manwë. (An angel of the Lord, basically.) Eönwë invites Eärendil into the divine palace, where he stands before the Valar themselves and makes his caseEönwë by redreyenotarget. “Please, for the love of Eru, help us!” And for once, they agree: The Valar will officially Intervene and help Middle-earth with its Morgoth problem.

Eönwë by @redreyenotarget

I know it’s easy to hate or blame the Valar for their apathy, but try to see this whole situation from their perspective: They spent the first couple eons of their time in Middle-earth trying to clean up Morgoth’s messes. Every time they succeeded, he would just fuck it up again for shits and giggles. And he’s more powerful than the rest of them combined. It’s just not worth their time to deal with their brother’s stupid shit. And for what? To help Men who are going to die anyway, Noldor who rejected their help and protection and who committed heinous atrocities, and some other Elves who never bothered to come to Valinor in the first place? You’d be demoralized too, if you realized that the world is never really going to be fixed, and people are always going to choose the worst possible options, no matter what you do. Hell, I feel that way, and I’m not a god. Also, as we’re about to see, there’s another, better reason why the Valar don’t help all that often.

What makes them say yes to Eärendil? I don’t know. Maybe they see the scale of the problem — that the survival of the Children of Ilúvatar is hanging on by a thread — or maybe they’re simply moved by his words. However, there’s a catch: the fate of Eärendil himself. Mandos declares that no mortal Man can come to the Undying Lands and live. On top of that, Eärendil is the son of Idril and the grandson of Turgon, making him technically a Noldo. And the Noldor are officially Banned From Valinor, on account of… *gestures vaguely*… everything.

Manwë delivers his judgement: Eärendil and Elwing will not be punished, because they came to Valinor with pure intentions, out of love and a desire to protect others. But he also can’t just let them off the hook. Eärendil and Elwing are forbidden from returning to Middle-earth.

There’s also the matter of their mixed heritage. Eärendil and Elwing are both Halfelven, with both Elven and human parents (or grandparents). Remember, the difference between Elves and Men is a metaphysical one: Elves are immortal, but permanently tied to Middle-earth. Men are mortal, but their souls will survive the end of the world, and participate in the creation of the next one. Manwë gives Eärendil and Elwing, and their sons, the ability to choose which destiny they want.

During all of this, Elwing made friends with the Teleri, and tells them all about Doriath and Gondolin and everything else that’s happened in Middle-earth. Eärendil comes to get her, and brings her to Manwë’s palace to make her choice. Elwing chooses to be an Elf, and Eärendil also chooses to be an Elf for her sake, even though he feels a stronger connection with Men.

Eönwë gets the Vingilot (sending Eärendil’s mariners home in another boat), and brings it to Eärendil. The magic of the Valar makes the ship glow bright white, like it’s filled with celestial fire. Eärendil sits at the helm, literally sparkling with all the diamond-dust on his clothes, and the Silmaril still on his brow. He sails out past the “uttermost rim” of the world, through the Door of Night, and into the void. In the morning and evening, he comes back to Valinor, which is why you can see him shining over the horizon.

The Voyage of Eärendil by @wavesheep

Elwing doesn’t join him on his voyages into the void, but she stays in Valinor, waiting for her husband to come home. In that time, she learns to speak the language of the sea birds, and they teach her how to fly. She flies up to greet Eärendil’s ship on white wings.

So now, you can understand the full significance of Sam’s line in The Two Towers:

“Beren, now, he never thought that he was going to get that Silmaril from the Iron Crown in the Thangorodrim, and yet he did, and that was a worse place and a blacker danger than ours. But that’s a long tale, of course, and goes past happiness and into grief and beyond it — and the Silmaril went on and came to Eärendil. And why, sir, I never thought of that before! We’ve got — you’ve got some of the light of it in that star-glass that the Lady gave you! Why, to think of it, we’re in the same tale still! It’s still going on. Don’t the great tales never end?”

Yes, Samwise Gamgee uses the light of a Silmaril, the last remaining light of the Two Trees of Valinor, to defeat Shelob, the daughter of Ungoliant. He uses it to force his way into Cirith Ungol, while singing the name of Elbereth, the Vala of the stars.

Back in Middle-earth, Elros and Elrond are not dead. They were adopted by Maglor (the second-oldest of Fëanor’s sons, who hasn’t individually done anything important until now). There’s something more than a little weird about being raised by the person who sacked your city and killed everyone you love — even the text itself points this out — but this is Maglor’s way of working towards the smallest bit of atonement. He and Maedhros don’t want a repeat of what happened with Dior’s sons. And Maglor genuinely grows to love the boys like they were his own children.

Maglor by @aamuusva

When the people of Middle-earth see the evening star rise for the first time, Maedhros immediately recognizes the light as that of the Silmaril. He and Maglor conclude that if the Silmaril miraculously rose into the heavens, where everyone can see it and it’s safe from Morgoth, they should take that as a good omen. (Not only is it safe from Morgoth, it’s also safe from them. They can’t literally climb into the sky to steal it from Eärendil’s crown.)

Seeing the evening star, Morgoth is genuinely worried for the first time in a long time. But he’s so arrogant, he doesn’t consider that the Valar would openly challenge him again. They’re happy in their paradise, and don’t care what Morgoth does over in Middle-earth. Plus, they hate the Noldor. Morgoth gives himself a big pat on the back for that one. He assumes the Valar would never stick their necks out for the Noldor again, because he’s evil, and he can’t understand forgiveness or compassion. As usual, mercy is the highest good in Tolkien’s world.

The Elves of Valinor prepare for battle. The Noldor of Valinor, the ones who never followed Fëanor into exile, are led by Finarfin. There’s also a host of Vanyar, the first group of Elves to arrive in Valinor. They’re led by Ingwë, the last standing of the three Elven kings who originally came to Valinor.

(Another Germanic Fun Fact for you: Ingwë is named after the god Freyr, who’s sometimes called Ing, Ingvi, or Yngvi. Variations on it are a common theonym in Germanic languages. I can’t believe I didn’t catch that back at the start of the book!)

There’s also a handful of Teleri, though not many. They still haven’t forgiven the Noldor for the Kinslaying and the destruction of their ships, and who can blame them? Elwing convinces some of them to contribute, since she’s distantly related to them, but they only send enough mariners to sail the Elf armies over to Middle-earth.

The army comes. The Valar are beautiful and terrible, and their footsteps shake the mountains as they march towards Middle-earth. Eönwë blows his trumpet, and the War of Wrath begins.

The War of Wrath by Firatsolhan

This is the biggest and greatest battle that has ever, or will ever take place in Middle-earth until the battle that ends the world. All the armies of Men and Elves, from Valinor and Middle-earth, participate in this battle. For once, they have the upper hand. Almost all the Balrogs are wiped out, save a few that scurry into the dark tunnels under the earth (to be found by Gandalf and co. millennia later). Most of the Orcs are slaughtered “like shriveled leaves in a burning wind.”

Seeing that he’s losing, Morgoth unleashes his trump card: If you think Smaug is bad, you’re not ready for the biggest, baddest dragon in Tolkien’s lore: You know ’im, you love ’im, please give it up for… ANCALAGON THE BLACK!

Ancalagon the Black by Ruben de Vela

Oh yeah! This is the kind of massive, horned demon dragon that you’d expect to see in a battle like this. This dragon is the size of an entire mountain range. This dragon makes Smaug look like an iguana. All seems lost, but then Eärendil himself comes down out of heaven with a host of Eagles, led by Thorondor. Together, they fight Ancalagon and the dragons in the sky. Eärendil himself slays Ancalagon, and the dragon’s enormous body falls upon the Thangorodrim, snapping their tips off. (If you’re gonna be a legendary hero, you need to get your dragon slaying in.)

After a day and a night, the battle is over. The sun rises, and Morgoth is defeated. He runs like a coward and hides in Angband, until the Valar drag him out and cut off his feet. They bind him with the chains that they once used to bind him in Valinor, and remove the remaining two Silmarils from his crown.

And that’s it. The Dark Lord is defeated.

Melkor by Elveo

(I tried to save this picture for a moment in which Morgoth arrives to fight, all badass, but nope. He’s too much of a coward for that. Good job, Morgoth, you suck so much that this picture makes you look cooler than you really are. Still a cool picture, though.)

His defeat came at a very high cost. The battle was so intense that Beleriand itself was destroyed. The entire westernmost part of the continent was ripped to pieces, and what’s left of it is swallowed by the sea. This is why the Valar don’t intervene often: when they do, the world as we know it is physically destroyed and reshaped.

Eönwë invites the remaining Elves of Middle-earth to come to Valinor. Last call. Maedhros and Maglor both refuse. They’re still compelled by their oath — they have to retrieve the Silmarils, even from the Valar themselves. They beg Eönwë to surrender the Silmarils to them, making the case that because their father made them, the Silmarils are their birthright. Eönwë responds that they no longer have that right. They committed so many atrocities in the name of the Silmarils that they don’t deserve them anymore. Their cruel sacking of Doriath and the Havens, in particular, damned them. Their only remaining option is to return to Valinor and face Manwë’s judgement. Then, and only then, will Eönwë give them the jewels.

Maglor decides to submit. He’s sad and exhausted, and hopes that the oath will let him bide his time indefinitely. Maedhros worries that if they return, and the Valar don’t forgive them, then they’ll be permanently stuck in an impossible position: they’ll be compelled to get the Silmarils, but won’t ever be able to access them. Whether they fulfill the oath or break the oath, they’re damned either way. They decide that the safest option is to simply steal them. They sneak into Eönwë’s camp at night, and literally just steal the gems, killing the guards and making off into the night. They’re caught, but Eönwë prevents anyone from killing them. Finally, finally, after all of that, the sons of Fëanor have their hands on the Silmarils! There’s only two of them left, and two of the three Silmarils left, so, one for each of them.

But as Maedhros takes the Silmaril, it burns his hand, because no evil thing can touch it. In that moment, Maedhros comprehends just how far he’s fallen. He cries bitterly, and in his despair, casts himself into a fiery chasm, taking the Silmaril with him into the depths of the earth.

The Death of Maedhros by Kamehame

I’d make a “cast it into the fire” joke here, but I don’t want to make light of this. Maedhros is such a tragic character, even by Silm standards. TV Tropes calls him one of the main villains of The Silmarillion, and I think that’s accurate. While Morgoth is the looming threat in the background, the Fëanorians are a much more personal, and sometimes more dangerous, threat. Maedhros in particular emphasizes the devastating tragedy of the Oath of Fëanor, because he’s not as much of an asshole as some of his brothers. For most of the story, he genuinely tries to do the right thing: he abdicates rulership of the Noldor, attempts to unify Elves and Men, and makes good decisions during war. He survives hell and despair once, and comes back stronger. He tries, but it’s not enough. He still destroys two Elven kingdoms (without Morgoth having to lift a finger), killing thousands of innocents, all for the sake of an ancient vanity. At the end, he realizes he is not a good person, that maybe he never was. That it was all for nothing.

His story illustrates how even a “good” person is still capable of evil — how passion, fear, anger, or a sense of honor can drive us to do terrible things, because they feel compulsive. We may claim to be compelled by internal or external forces, but we are still ultimately responsible for our own actions and their ripple effects. It’s unclear whether the oath really does have some kind of magical hold over Maedhros, or whether he only believes it does. Ultimately, it doesn’t make much of a difference. It’s your call whether he succeeded in mitigating the oath’s effects, or whether he was every bit as bad as his father and brothers, while pretending not to be.

It Ends in Fire by Jenny Dolfen

As for Maglor, his hands are also burned by the Silmaril, so he throws it into the sea. He cuts himself off from the rest of the world, and walks the edges of the shoreline, playing on his harp and singing laments. We’re not told what happens to him after that. There are those (in the fandom) who say that Maglor still lives, still wandering the edges of the sea and singing.

Maglor by @redreyenotarget

The Silmarils find their final resting places: One in the air, one in fire, and one in the sea.

Most of the remaining Elves sail West, and are welcomed to Valinor. They live on Tol Eressëa, the island just off the coast of Valinor. They build a city on the island called Avallónë, which means “near to Valinor,” but… c’mon… “Avalon.” (Real subtle there, Tolkien.) Manwë finally pardons the Noldor, and the ancient Curse is officially null and void.

A handful of Elves choose to stay in Middle-earth. Among these are Círdan, Celeborn, Gil-galad, and Galadriel. Galadriel is the last of the original group of Noldor who were exiled from Valinor (except Maglor, I guess). The forgiveness of the curse applies to her, too, which is why she’s able to sail West at the end of The Lord of the Rings. But for the time being, she remains in Middle-earth with her husband.

Elros and Elrond, the half-elves, are given the same choice as their parents. Elrond chooses to be an Elf, and Elros chooses to be a Man. Elros’ line is particularly epic, because it’s the only line of Men that has both the noble Noldor blood and the divine blood of the Maiar. It eventually ends in Aragorn. On the other hand, imagine how Elrond must feel: He loses his parents early to their divine sea voyage, his foster fathers to the despair over their curse, and then his brother to the world of Men and a mortal life. And then, after several millennia, he loses his daughter, who makes the same choice to become human! (Arwen is able to do that because she’s Elrond’s daughter; not just any Elf could do that. Also, yes — Aragorn and Arwen are technically first cousins, but so many generations removed that it doesn’t matter.) At least Elrond is eventually able to reunite with his wife and sons in the Undying Lands.

Meanwhile, Morgoth is thrown through the Door of Night and into the Timeless Void. The Valar aren’t going to make the mistake of forgiving him a second time! He’ll wait there in the dark, gnashing his teeth, until the end of the world. Unfortunately, the damage was done: Morgoth planted the seeds of evil and hatred and fear in the hearts of Men and Elves, and that capacity for evil will continue to do harm until the end of days. And of course, as we all know, there’s another Dark Lord to deal with…

With the War of Wrath, the destruction of Beleriand, and the near-permanent imprisonment of Morgoth, the First Age comes to an end. With it ends the Quenta Silmarillion proper. It ends on a sad note. The last paragraph emphasizes that the whole story has been about the decay and destruction of what was once beautiful, and that this is the fate of the world. The world is Fallen, and if God (Eru) intends otherwise, the Valar have not declared it. That is very depressing.

But wait! There’s more! We haven’t even gotten to Númenor yet…

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did Sauron have Shelob as a middle-finger to Morgoth?

Like, I doubt Morgoth liked spiders in any form with all the Ungoliant stuff.

And here's Sauron taming a spider, "I'm superior to these creatures!".

Yes it's not as huge or powerful as Ungoiliant but I think he's saying something.

523 notes

·

View notes

Text

But Celegorn said: 'Know this: thy going is in vain; for could ye achieve this quest it would avail nothing. Neither thee nor this Man should we suffer to keep or to give a Silmaril of Fëanor. Against thee would come all the bretheren to slay thee rather. And should Thingol gain it, then we would burn Doriath or die in the attempt. For we have sworn our Oath.' - The War of the Jewels, "The Grey Annals"

Tolkien in Color: The House of Finwë (part 10/x) < part 9 ||

for @cnc-week

377 notes

·

View notes

Text

“But the land of Aman and Eressëa of the Eldar were taken away and removed beyond the reach of Men for ever. And Andor, the Land of Gift, Númenor of the Kings, Elenna of the Star of Eärendil, was utterly destroyed.” - the Silmarillion, J.R.R. Tolkien

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Again therefor in his pain Maedhros begged that he would slay him; but Fingon cut off his hand above the wrist, and Thorondor bore them back to Mithrim.”

Silmarillion – Of the Return of the Noldor

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to be the very best, like no one ever was

Fëanor invented pokéballs and also the pokédex.

Close ups under the cut!

307 notes

·

View notes

Text

“At that time Nimloth was dark and bore no bloom, for it was autumn, and its winter was nigh; and Isildur passed through the guards and took from the Tree a fruit that hung upon it, and turned to go.” - the Silmarillion, J.R.R. Tolkien

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

IDEA: The Silmarils were, in fact, crystal containers with either:

- fluorescent proteins, or (even more likely)

- luciferases (proteins that catalyze chemical reactions producing light, e.g. in fireflies or jellyfish)

because that's probably how the Trees could shine in the first place.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday❤️❤️ ❤️ @dalliansss

Thank you so much @sauroff for those two wonderful commissions!

Finrod/Maedhros

Aegnor/Fingon

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's ignore the fact that Tolkien is a complete idiot at biology. Tolkien only showed two families in the elven genealogy where twins are born. Nerdanel and Nimloth. And Nimloth' family keeps having twins. Nerdanel's family… well, We don't know because they all died! For now, let's focus on Nimloth. Identical twins have no genetic influence, but fraternal twins are usually inherited through the mother's body type. Nimloth' daughter Elwing gave birth to twin sons, and Elros, the son, can't decide whether his children will be twins, but he can pass on his mother's body type to his daughter. Even Elwing's son married Nimloth' relative and had twins. Well, incest is a royal trademark. And since there's no description of the twins in that family looking exactly alike, it seems like Nimloth' family is a family where fraternal twins are often born.

On the other hand, the sons of Feanor look like identical twins, as there are descriptions of them looking so similar…..but that may not be the case. There are descriptions of them looking eerily similar, and also of their hair colors being different. If they are also fraternal twins too….. The lineage of Nimloth and the lineage of Nerdanel may actually be related. Of course, the elves are all related because Tolkien made a mistake in the setting, but let's move on. Among them, they may be more related. If we use our imagination, there were fraternal twin sisters, and one of them crossed the sea and married Mahtan, and the other followed Thingol. And they passed on their constitutions……

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

If someone is a necromancer its cuz they have no money to hire men and no charisma to convince people to their cause u have to understand they only fuck with skeletons because they have no other option

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

When it became clear at last that Míriel would never of her own will return to life in the body within any span of time that could give him hope, Finwë's sorrow became embittered. He forsook his long vigils by her sleeping body and sought to take up his own life again; but he wandered far and wide in loneliness and found no joy in anything that he did. - The Peoples of Middle-Earth, "The Shibboleth of Fëanor"

Tolkien in Color: The House of Finwë (part 1/x) || part 2 >

848 notes

·

View notes