A digital humanities work-in-progress on Witch Films in U.S. film and media by Tess Henthorne, Bridget Sellers, and Elizabeth Crowley Webber

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Project Updates

Digital Witchcraft is… nearly digital! We’ve started web design in collaboration with Benjamin Liden and are close to completing the first phase of the project.

In this initial phase, we trace the selection process for our corpus of Witch Films before analyzing visual and textual similarities among the six films we’ve chosen as proof of concept: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), The Witches of Eastwick (1987), The Craft (1996), Halloweentown (1998), The Blair Witch Project (1998), and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (2001).

Next week we’ll use Amanda Phillip’s graduate level digital humanities seminar at Georgetown University to present our findings from the first phase of Digital Witchcraft and share continued plans for the project.

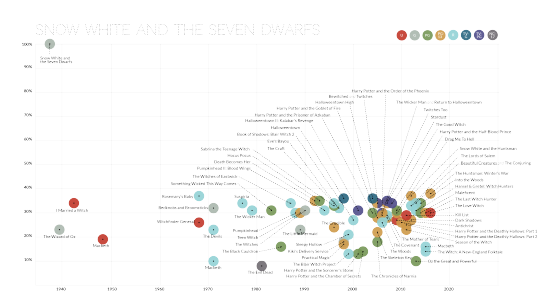

Stay tuned for updates and information about our live site. In the meantime, check out a sneak peak of our data visualization that shows textual similarity to Snow White.

0 notes

Text

Charts and Graphs, Part 2.

After some feedback, we’ve decided to scrap (for now) the petal graphs. It sounds like all in all, most readers have a hard time understanding what exactly those are showing. By comparison, the scatterplots appear to be highly readable. It’s exciting to see these coming together and begin to really reveal which films are using similar language.

0 notes

Text

Ethical Approach

Since the beginning of this project, we have tried to ethically orient ourselves to the subject matter. This has forced us to think and rethink what a witch film is, what a witch is, and what it means to talk about witchcraft in American media.

Since we decided to base our definition of a “witch film” on public opinion, we had to take into account the biases of the public. For example, this meant that almost all of the films on our list were about white women. This also meant that we did not include films that might include content that seems witchy in nature but does not explicitly use the witch label. We choose to identify and highlight these biases, rather than pushing them under the rug.

It is also important to us that we consider how witch films and the experiences of marginalized groups are tied. For example, we have tried to approach our work keeping in mind the differences between representations of witches in media and the lived experiences of Wiccans in America. We also work under the impression that the the witch as a figure is defined by their difference. The ideas of persecution and paranoia that are tied to the witch figure are also historically bound to American investments in structures of power and stabilized norms. The witch is both precarious and disruptive, both empowered and constantly maligned by those in power. Ultimately, what gives the witch figure its power and cultural currency is the lived experiences of marginalized groups.

With this in mind, we have tried to orient our project in terms of the way big film companies use and abuse the witch figure and witch narratives. On the one hand, it would be easy to simply look at the 80′s and 90′s boom of witch films and celebrate what it says about, for example, American feminism. Instead, we want to note that companies saw the popularity of the witch figure/witch narrative and sought to reproduce it for their own gain. This itself is closely connected to the white-washing and domestication of media representations of witches. Though one may rally behind a media representation of a witch as a symbol, we hope to always be aware of how these representations are used by those who are not invested in the wellbeing of marginalized groups.

0 notes

Photo

We’re working on visualizing the cosine similarity scores (which we’ve found using SameDiff), and have realized that percentages seem to make the most sense. In this scatter plot, we’ve played around with Halloweentown (The Disney Channel, 1998). You can see how close the different witch films are based on language usage and when the movies were made. It looks like there’s a cluster of more similar movies after Halloweentown aired. The most similar movies are, unsurprisingly, Halloweentown II: Kalabar’s Revenge (2001) and Halloweentown High (2004). But Twitches (2005), another Disney Original Movie in the same-ish historical moment, is also fairly similar.

The second way we represented the similarities was using a petal chart, placing stars to represent how close each movie is to the central film. In an ideal world, this would be a live image that allowed users to click on the stars in order to reveal the exact percentage.

On a purely semantic level, then, it appears that our visuals and the cosine similarity scores highlight a cycle of made-for-television, teen witch movies. Introduced by Halloweentown, these movies are about a girl (or girls) who discovers she’s part of a family of witches. The cycle was clearly repeatable at a semantic level, and based on the Disney Channel’s decision to continue to reproduce this kind of movie, we can presume its popularity.

0 notes

Link

We’re currently using Voyant to generate a list of the potential semantic similarities across the corpus.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Text Collection

After several weeks of effort, we currently have fan transcripts saved for all of the Witch Films that we plan to compare. As mentioned in our “Troubleshooting” post, there are several affordances of using fan transcripts (versus scripts or shooting scripts):

Transcripts typically do not record information about action or instructions for the camera, and so when we compare transcripts we are comparing only final dialogue. Thus, the cosine similarity scores between transcripts ought to determine the similarity between the spoken words that viewers hear. For the sake of our project, this is a more interesting comparison than, say, that between shooting scripts, which include a lot of extraneous information.

Fan transcripts proved much more reliable than other potential captures of dialogue, particularly closed caption data. Many CC files were garbled, especially in the case of older films. (In many cases, such as with The Witches of Eastwick, the fan transcripts appeared to have been rendered from closed caption data and then edited by a fan. In these situations, we removed time stamps from the file but left the rest of it intact.)

By looking for fan transcripts, we are once again allowing the audience and the internet to lead us toward popular films (as we’ve done with the creation of our initial list of films and with the selection of images). This means that while we believe that, say, Little Witches (Jane Simpson, 1996) should have been included in the comparison, it won’t make it into our digital analysis because no fan transcript is available for that film. The availability of a fan transcript acts as a kind of filter, limiting us to only those films that have a popular following.

When looking for transcripts, we tended to have a lot of luck with Drew’s Script-O-Rama, Springfield! Springfield!, and Fandom.* If multiple scripts were available, we attempted to discern which appeared to most accurately represent the dialogue. After locating a script, we copied it from the web and pasted it into a Text Edit file.

As far as text cleanup goes, we removed all apostrophes from each file. (As mentioned in our “Troubleshooting” post, SameDiff does not read contractions.) Unfortunately, this turned “he’ll” into “hell” and “I’ll” into “Ill,” so we’ll need to go back in after we run word occurrence data and account for that. After removing all apostrophes, we did a quick scroll through each file to ensure that nothing appeared incredibly amiss after pasting the text into the file. This is when we realized that in a cluster of transcripts circa 2005, the lowercase “L” and an uppercase “i” had been transposed. (So it appeared as if the word I’ll was in order, but it was actually L’ii.) We did global searches for i’s and L’s in each transcript and corrected for this error. Then we saved as a plain text document and uploaded to a Google Drive folder.

A link to all of the locations for the fan transcripts can be found in our Witch Things spreadsheet.

* For scripts and shooting scripts, there are several less robust options, including IMSDB and the American Film Scripts Online database. We are indebted to Melissa Jones at the Georgetown University Library for her help throughout the text collection process. The library’s Film and Media > Scripts & Archives page was also quite useful.

0 notes

Text

Image Collection

We’ve started the process of data collection! To analyze visual elements of Witch Films, we are collecting images in two categories: film stills and theatrical posters.

These two categories have evolved throughout the early phases of our work-in-progress. As we mentioned in our discussion of Troubleshooting, we originally planned to examine a single shot from each film on our list of Witch Films, hopefully a shot that would show the witches at a defining moment from their respective films. This idea prompted various logical questions. Do we watch every movie to determine the climax, where the witches are at their peak “witchiness,” and use a still from that scene? What do we do with films like The Blair Witch Project, which never shows a witch on screen? Are we reinforcing stereotypes of witches if we only look for shots that feature a witch behind her cauldron?

Hermione Granger in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

Photo Credit: Warner Brothers

Because this process would have been relatively biased—there isn’t one objective way to determine peak “witchiness”—we’ve crafted a methodology that is more dependent on discourse about Witch Films. We are collecting the first image return from a Google Search for “[film title] + film still.” We chose this process because results are partially curated and partially random. Although the Google Search algorithm is influenced by factors like the computer’s previous search history, it ranks pages based on their relevancy to search terms and minimizes bias. We also conducted our search from the same computer over a one-day window to eliminate differences between browsers on different computers and any changes to available results. While our methodology is streamlined, we’ve still had to make editorial decisions:

When an image is noticeably blurry, we’ve found the identical image with a higher resolution.

When the first image return is a poster, not a film still, we’ve selected the first still that appears in a Google Search.

In case the top return changes, we’ve noted the date that we searched for and downloaded the image result.

We’re also recording the source of each image. Since our project is interested in fan studies and audience reception, we want to track who is writing about the images that show up in a search.

Our collection of theatrical posters has required less editorial intervention. We’ve decided to pull all images from the film’s page on IMDB. Since there are often multiple posters distributed for a film—like teaser posters and character posters—this approach has ensured that we’re looking at a poster deemed representative of the film and will allow us to study contemporary reception and marketing of Witch Films. Similar to the film stills, we’ve recorded when we downloaded the image in case IMDB makes changes to these pages in the future.

The next step is to run our images through ImagePlot, a tool to examine trends and similarities within clusters of images. Check back for updates soon!

0 notes

Text

Troubleshooting

Over the course of planning this project, we’ve come across several roadblocks that have constrained how we’ve moved forward. Some of these were larger concepts, while others were practical limitations. For instance, we originally conceptualized this project as a large scale examination of the “witch aesthetic” across media catageories, including video games, books, films, television, and blogs. Though we would still like to extend our research to some of these categories, we had to limit ourselves to film because there was just so much material out there.

Meanwhile, we realized that it would be extremely time consuming to try to watch every film before determining whether it was a Witch Film. Instead, we decided to rely on what others determine counts as a “Witch Film.” So we used lists of films created by other groups, such as IMBD and Vulture. Because of this, we began to consider our project as an approach that centers public opinion.

But this approach comes with its own drawbacks, including the prejudices of the public. However, we’re hoping to use this particular roadblock to highlight how Hollywood exploits the concept of witch (which is inherently tied to marginalized groups) while excluding many of those groups from how the witch is represented (most Witch Films, for example, feature heterosexual cis white women).

With our image data, we struggled to find a way to compare images in films. We considered curating the images ourselves (which would definitely bias which kind of images we would study). We also considered taking stills from important parts of the film, such as the opening shot, the closing shot, and the shot in which the witch appears. But since many films categorized as ‘Witch Films’ didn’t show the witch at all (looking at you, Blair Witch Project), this proved complicated as well. Finally, we landed on picking one movie poster (using IMBD rather than trying to track down original posters) and the most popular film still from each film (using the plain old Google image search).

We also realized it would be impossible to get consistent scripts across all the films (some screenplays are locked behind paywalls, some scripts don’t reflect the final product, and lesser known films often don’t have legitimate scripts available), so we limited ourselves to fan transcripts, many of which come from closed captioning data.

Today, we started using our text comparison tool (SameDiff). When we began to use it, we realized that some of the text files we were using had words bleeding together. We also realized that our comparison tool didn’t recognize contractions, so we had to go through the files to edit out the apostrophes. This forced us to clean up the scripts a little more than we’d intended to, but we cut ourselves off when it came to fixing spelling errors, because that would ultimately change the status of the script as “fan transcript.”

These are just some of the roadblocks we’ve come across so far in the project. There will definitely be more troubleshooting ahead, but also more new and exciting developments. Stay tuned!

#DH#digital humanities#troubleshooting#witches#witch films#film#cinema#film studies#media studies#witchcraft

0 notes

Text

Project Pitch

As part of our process, we used Amanda Phillips’s graduate-level digital humanities seminar at Georgetown University as a sounding board for our project. Our basic pitch is to use the digital tools SameDiff and ImagePlot to look at the language and imagery of Witch Films in the United States.

One question posed by our peers was about our definition of “Witch Film.” If genre is how an audience defines it (or, in the words of Andrew Tudor, genre is “what we collectively believe it to be”) then we can rely on fan-produced lists to do this definitional work. We used Google, Vulture, and IMDB to build our initial corpus of films, adding additional titles as we come across them in our research.

Of course, this is really reliant on our usage of the internet, where we decide to click and the search terms we decide to use. And, this leaves out some stellar films, including independent and foreign ones. But our project is looking at the ways genre films co-opt the image of the witch—an image important to people of color, the LGBTQ+ community, Wicca, and practitioners of witchcraft. We’re choosing to look primarily at popular cinema (again, those films that appear readily in internet searches), which we hope will provide evidence for capitalism’s (ab)use of these marginalized groups.

Another question arose about culling this list. For example, someone pointed out that both Sleeping Beauty (Clyde Geronimi, 1959) and Maleficent (Robert Stromberg, 2014) technically features a fairy, not a witch. Again, we’re letting audience define what is or is not a Witch FIlm. Because popular culture defines these two movies as Witch Films, we’ve included both of these films in our corpus. In short: We aren’t doing much culling, except for removing films that appeared in searches but were not released in English.

Or project is to compare the similarity of dialogue (via fan transcripts) and images (via film stills and theatrical posters). So far, we’ve generated an inclusive list of films that we’re working with, along with metadata that includes the year, studio, director, writer, gross receipts, and gross receipts calculated for inflation. We’ve also done a lot by way of gathering images, and are hoping to experiment with ImagePlot over the next week.

The next step is to continue to gather transcripts of the films. Because The Witches of Eastwick (George Miller, 1987) appears to be a watershed moment for Witch Film production, we’re starting there and working our way up to the present. Amanda Anna Klein makes a convincing case that genre film cycles happen in 5–10 year periods. So, once we get transcripts gathered through 1997, we’ll start running scripts up against The Witches of Eastwick in SameDiff.

Photo credit: Warner Brothers/Photofest

The Witches of Eastwick

1 note

·

View note

Link

This is the home of “Digital Witchcraft,” a digital humanities work-in-progress, a project that is attempting to create a method for mining visual and textual data extracted from Witch Films.

This link is for a spreadsheet of the Witch Film and Media objects that we’ve found so far. We hope that it’s an inclusive list, so will keep updating it as we find more movies and television shows that fit the definition of “witch” film, broadly defined.

This Tumblr is where we’ll note our progress, wins and losses. Stay tuned!

0 notes