Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

A Series of Unfortunate Events by Michael Wolf (2010)

Wolf spent hundreds of hours searching through Google Street View, to create this series of images displaying bizarre occurrences throughout the world that have been captured by the cameras mounted on the top of Google’s special GPS-coordinated Street View camera vans.

via: welcome.jpeg

672 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The erasure of the individual through the quantification of the dead is also explored in Coco Fusco’s work Your Eyes Will be an Empty Word. The work comprises of a video featuring the artists rowing alongside Hart Island in a rowboat. Hart Island is the largest mass gravesite in the United States, and it is where New York’s unclaimed victims of COVID-19 were buried. As Fusco rows along the island, she tosses white carnations into the water to memorialize those left alone in death. Her work features various aerial shots of the island, and the sheer size of the island pushes against the rational aesthetics of counting the dead. Although throughout the height of the pandemic, death tolls were a key metric used to provide comfort to individuals, this video makes us aware that counting the dead may not be as comforting as we hoped. Fusco’s video makes us uneasy rather than comforted because although the dead here were counted, they were not properly memorialized. The dead are massed together, and we do not know what their names were or what kind of people they were. Works like Fusco’s and Gonzalez-Torres’ offer us a different perspective on the rational aesthetics of counting the dead. More specifically, it shows us how even though we may count the dead, there remains a lot of work to be done in memorializing those we count.

Coco Fusco, Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word, 2021, HD video, color, sound, 12 minutes. From the Whitney Biennial 2022: “Quiet as It’s Kept.

209 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Trevor Paglen, “‘Fanon’ (Even the Dead Are Not Safe) Eigenface” (2017), dye sublimation metal print

Trevor Palgen is an artist and geographer who explores such themes through his investigations into surveillance apparatuses. In doing so, his art offers a “perverse voyeuristic satisfaction of watching the systems meant to watch you” (Burke). My exhibition features several of his works yet they all center around the same goal of making viewers more cognizant of the ‘datafication’ of people. One of the works, titled Fanon (Even the Dead Are Not Safe) Eigenface, creates a portrait or what he calls a “face-print” of philosopher Frantz Fanon. The portrait looks very uncanny as it only vaguely resembles Fanon, yet this is exactly the point. Palgen transforms Fanon’s face into an eigenface which is a unique set of eigenvectors that allow a computer to facially recognize a person. In essence, facial recognition technology breaks down each person’s face to a set of unique eigenvectors based on facial traits. Thus, the technology takes one’s face and breaks it down into a set of data points. This dataset is then stored in memory so that when the person attempts to use the facial technology again, the computer recognizes who the person is. Palgen’s ghostly portrait of Fanon uses the data that a facial recognition technology would store of his face. Thus, Fanon is reduced to the set of eigenvectors that make his features mathematically distinct from other faces. The work’s title Fanon (Even the Dead Are Not Safe) Eigenface, warns viewers that even Fanon, who died before facial recognition was developed, is not immune from getting turned into a dataset in order to have his face tracked.

Trevor Palgen’s work and the aims behind his art serve an important purpose. Jose van Dijck’s article “Datafication, dataism, and dataveillance” illuminates an age of increasing dataveillance which is “a form of continuous surveillance through the use of (meta)data” (198). A person’s eigenface can be considered metadata about their face, and thus allowed to be tracked by the government. The difference between dataveillance and surveillance is that surveillance assumes monitoring for explicit purposes while dataveillance allows for “the continuous tracking of (meta)data for unstated preset purposes (van Dijck 205). The title of Palgen’s work Fanon (Even the Dead Are Not Safe) alludes to the idea that facial recognition is dangerous. As van Dijck’s article shows, the datafication of our bodies through technology like facial recognition has opened the door for a new kind of surveillance. This dataveillance is a more dangerous kind of surveillance because it is largely unrestricted and does not need a specific goal. People thus become tracked for tracking’s sake, and Palgen’s work attempts to make us, as viewers, aware of this reality.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

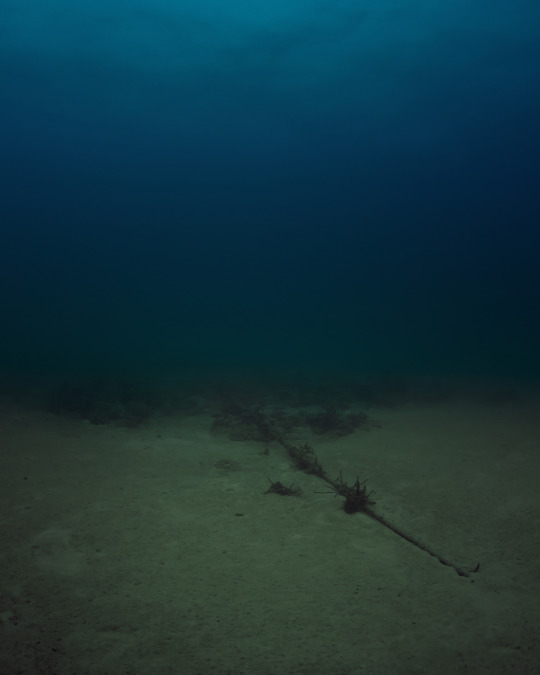

Trevor Paglen, “Bahamas Internet Cable System (BICS-1), NSA/GCHQ-Tapped Undersea Cable, Atlantic Ocean” (2015), c-print, 60 x 48 inches (image) (courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures)

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Trevor Paglen, “It Began as a Military Experiment” (2017), set of 10 pigment prints, glossy finish (all images courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures)

0 notes

Photo

Margolles’s work comprises of a stillborn child encased in a concrete block. Her work begs the questions what part of life have we not infiltrated and commodified yet? The piece creates demand where naturally there should not be any and “demonstrates that the social inequalities suffered by the poor and disenfranchised continue after death.” Burial shows how death is not the great equalizer and how we value lives translates to how we value the dead.

Teresa Margolles, Burial (Enterrement)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jenny Saville’s Propped, made in 1992, is a nude self-portrait. The work does not depict Saville in a way that aligned with the aesthetics of the nude, rather it tows the line between a realistic portrayal of her body and abstraction. The nude became a codified style in art perpetuated by famous works like Pablo Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon and Edouard Manet’s Olympia. These works sexualized and idealized the female body, treating the body as something the male viewer should take pleasure in. Saville’s work pushes against the nude, by creating an exaggerated portrayal of her body. Saville’s knees and hands are proportionally much bigger than the rest of her body. Furthermore, the color palette of pinks and greys underscores the fleshiness of the body. Her legs are not depicted as thin and petite, but rather their fat and muscle are overexaggerated in the painting. Thus, her work interrogates standard conventions of beauty, specifically a cultural aversion to obesity. Society’s fear of obesity is largely attributed to the quantification of our weight and the quantified self-movement which seeks to constantly track our weight. Kate Crawford et al.’s paper “Our metrics, Ourselves” explains how the proliferation of the penny scale and the scale’s eventual transfer into the domestic created a culture of women having to be a certain weight. The penny scale gained popularity because it allowed people to quantify what their weight is rather than speculate. However, the scales move into the domestic sphere marked a shift in what the scale measured as it went “from what the person weights to what you should weigh and what you should be” (Crawford et al. 482). Thus, with the popularization of the domestic scale came a culture bent on achieving a target weight. The marketing of these domestic scales was specifically targeted towards women. A Health-O-Meter advertisement from 1925 featured an image of a young woman in her underclothes with the catchphrase “She doesn’t GUESS – She KNOWS” (Crawford et al. 488). The selling point that a scale gives women knowledge and thus is an important metric for women perpetuated a diet culture, one that did not exist before the 20th century. The obsession with women measuring and knowing their weight created by the proliferation of domestic scales is a theme Jenny Saville’s work is in dialogue with. Saville is highly aware of the type of body and weight society wants to see, and instead, her portrait offers the opposite. In doing this, her work asks what is the point of having an ideal weight and incessantly measuring our bodies? In conversation with the Health-O-Meter advertisement mentioned earlier, Saville’s self-portrait responds with questioning the value in knowing?

Born in Cambridge in 1970, Jenny Saville is a contemporary painter. She is known for her large scale portraits, often depicting very overweight bodies. After graduating from the Glasgow School of Art she received a grant to study in the United States at the University of Cincinnati, which is where she found her inspiration. Talking about this period of her life, she has said: “There were so many huge women. So much flesh just spilling out of shorts and t-shirts. It was good for me to see it; their physiques interested me so much.“Whilst at the head of Young British Artists (YBA) – the movement which made her famous in 1992 – she was supported by the famous Saatchi agency, whose owners are dedicated collectors of contemporary art. They spotted her while attending her graduation show, where Charles Saatchi bought her entire portfolio and invited her to exhibit them in his gallery. Today, she lives and works in Oxford.

In her compositions Saville transcends the boundaries of both figurative art and modern abstraction. She takes inspiration from Picasso, and sees in his works the same figures that she herself studies and produces. She is most interested in bodily imperfections and the social constraints and ideals around the female body which have led to the development of taboos and warped beauty standards.

Her interest in the subject developed throughout her childhood; she remembers studying bodies in works by Titian and Tintoretto, and noticing the chest of her piano teacher as it pressed against her blouse, becoming an abstract mass of flesh just like the ones she would eventually go on to paint. In 1994 she watched a plastic surgeon at work in New York, which allowed her to study the deconstruction and reconstruction of the body in depth.

This experience marked a shift in her art as she discovered the fragility of the body, and her perception of flesh changed. She became more analytical and began to explore medical problems; viewing bodies in the morgue and examining animals. Saville is interested in both classic Renaissance sculpture and her own daily observations of people of people pushing the boundaries of genre, as well as the interaction of bodies: entwined couples, the embrace between mothers and children…

https://www.artsper.com/…/united…/55222/jenny-saville

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Glen Luchford and Jenny Saville, Closed Contact A-D (four works), 2002

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The work consists of candies piled up in the corner of a gallery that weigh a total of 175, an ideal weight. The label lists the works ideal weight of 175, which corresponds to the ideal body weight of Ross Laycock. The work is meant to be engaged with by viewers as viewers are encouraged to take candy for themselves. The diminishing amount of candy over the course of the work’s display symbolizes Ross’s weight loss and suffering as he battled with AIDS. The artist stipulated that the pile of candy should always be replenished, allowing Ross to perpetually live on through this work. The work’s emphasis on weight connects back to my exhibition’s first theme. The artist uses the quantification of the body through weight to depict an ideal image of loss. The ideal weight of 175 that is included in the wall label is meant to represent the peak of Ross’s health. Thus, we see in this work how the scale and the quantification of weight has altered our entire perception of what it means to be healthy. Not only does this work tie in with my first theme, but it also explores a new theme of how we quantify the dead. The AIDS epidemic killed millions of people. Although the victims of AIDS were quantified, this quantification did not help their loved ones feel better about their death. If anything, it dehumanized the dead by turning their bodies into datapoints. Gonzalez-Torres made this work not only to mourn his partner, but also to ensure Ross Laycock was memorialized albeit by also turning him into a number.

“Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) is a 1991 piece by Felix Gonzalez-Torres in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s a spilled pile of candy.

“Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) represents a specific body, that of Ross Laycock, Gonzalez-Torres’ partner who died of AIDS in 1991. This piece of art serves as an “allegorical portrait,” of Laycock’s life.

The pile of candy consists of commercially available, shiny wrapped confections. The physical form of the work changes depending on the way it is installed. The work ideally weighs 175 pounds (79 kg) at installation, which is the weight of Ross Laycock when healthy.

Visitors are invited to take a piece of candy from the work. Gonzalez-Torres grew up Roman Catholic and taking a candy is a symbolic act of communion, but instead of taking a piece of Christ, the participant partakes of the “sweetness” of Ross. As the patrons take candy, they are participants in the art. Each piece of candy consumed is like the illness that ate away at Ross’s body.

Multiple art museums around the world have installed this piece.

Per Gonzalez-Torres’ parameters, it is up to the museum how often the pile is restocked, or whether it is restocked at all. Whether, instead, it is permitted to deplete to nothing. If the pile is replenished, it is metaphorically granting perpetual life to Ross.

In 1991, public funding of the arts and public funding for AIDS research were both hot issues. HIV-positive male artists were being targeted for censorship. Part of the logic of “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) is you can’t censor free candy without looking ridiculous, and the ease of replicability of the piece in other museums makes it virtually indestructible.

65K notes

·

View notes