my fics | translation | AO3 | linktreethe look on your face is somewhere between let’s start a revolution and i want to set this world ablaze — after further consideration they could possibly be the same; all i know is that if you ever looked at me that way, i would follow you anywhere.

Last active 3 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

when e.e. cummings said “i’ll live my life if it kills me”

125K notes

·

View notes

Text

you see this too right

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

fanfic writing culture isn’t “oh dang! I wanted to write about this prompt with this character but someone else already wrote it, so now I can’t”.

fanfic writing culture is always “two cakes is better than one. the more the merrier. there can ever be enough fics of this character with this prompt!”

50K notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a couple guys who like 2 wear each others’ clothes

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

tsoa

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

111K notes

·

View notes

Text

I miss them

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

when I comment on a fellow writer's fic and they, in turn, comment on one of mine

829 notes

·

View notes

Text

best m/f dynamic is a flamboyant bisexual show-off desperately in love with an extremely practical girl who’s difficult to impress 🤩

41K notes

·

View notes

Text

What a wonderful piece of media! Surely the fandom will be literate and normal

31K notes

·

View notes

Text

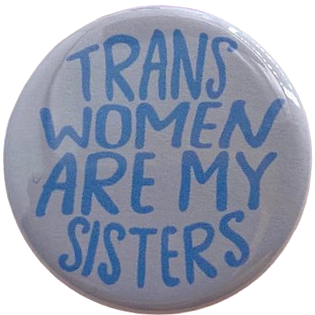

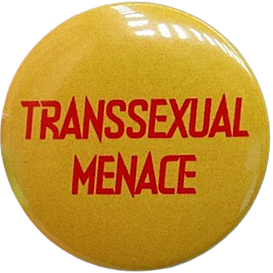

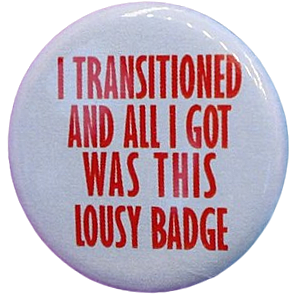

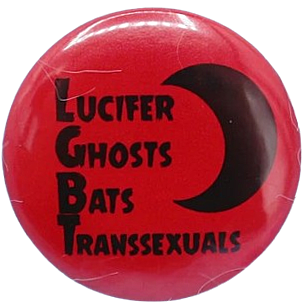

pins by Abprallen

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

"It’s all forgettable with just a single drink, and yet I always hesitate…”

#i feel like every other day i want to reblog this and go off in the tags about what this drawing in particular means to me but then#i get shy about being that vulnerable in the world wide web#so a lone rb it is and i'll let the drawing do the speaking i already feel like it's a little of my soul bare on a screen#<< prev i feel the exact same way#its hard#its a lovely portrait and id love to hear what youd have to say someday ^_^#← double prev#yah what they said!#thank you always for the gift of sharing your art and a bit of your soul with us <3

559 notes

·

View notes

Text

WIP Wednesday

Have a bit from Memory Unlocked

“I guess Menoetius did one nice thing for me,” Patroclus said as they entered his kitchen, yesterday’s wine glass still on the counter. “He gave me the opportunity and the excuse I needed to call you.”

Achilles flashed a great smile at him, but his eyes very quickly traveled past Patroclus’s face to land on something behind him that clearly troubled him, his brows furrowing first, then his lips losing their happy curl. Patroclus cringed when he turned his head to see it was Achilles’ drawing posted on the fridge that had caught his eye. He didn’t have any sort of explanation that would make taping it up make sense.

“I thought it was… funny,” he said. “Not the picture itself, just… A memento of a reunion that went terribly wrong. A sort of… dark humor thing, I guess.”

Achilles nodded slowly, as if accepting that explanation. He turned to Patroclus, took a breath, then let it out through his nose. He leaned back against the kitchen counter, his back to the fridge and their dashed teenage dreams. Looking off to the side toward the floor, he asked, “Out of curiosity, if I had been braver back then, what do you think would have happened?”

Patroclus was surprised by the anger that flashed through him. Achilles, his best friend who had everything, who left him to go be with some girl, was asking Patroclus, as if Patroclus was the reason it didn’t happen? As if anything had been up to him at all? If they had actually been on some sort of trajectory that involved sleeping with each other, Achilles was the one who crashed it into the ground and left the wreckage unharmed.

But as he watched Achilles’ bashful face, the anger faded. He moved a little closer to him. He put his hand on his shoulder. He told him the truth.

“I would have fucked the shit out of you.”

#patrochilles#IT'S HAPPENING#wip wednesday#I definitely have enough material to share something but idk if I should lol#I might get arrested for horny crimes

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

wasn’t going to drink tonight but I remembered that after Patroklos’ death, Achilles refused to eat or drink until he finally slays Hektor, both because he was so overcome with loss and grief, but also possibly because Patroklos was the only one in the Iliad who was described as preparing the meals and wine for Achilles, rather than a slave women that was typical during war to have done instead, so he perhaps can’t willingly stomach eating the food that someone else’s hand has prepared knowing that Patroklos wasn’t the one who did, symbolising the craved tie of domesticity and mortality that Patroklos provides Achilles that he loses when Patroklos does die. To Achilles, Patroklos was the part of him that made up his ties to mortality, as well as his honour and pride, when Patroklos dies, Achilles suddenly does not need for food and sleep and he feasts only on the merciless fury left within him, the wish to carve Hektor and eat him raw instead and to satisfy that need which ties him to the wrath of godlike immortality that does not require these humane needs. The things that tied him to mortality are all either gone or he no longer cares for them as much as he had, only striding to please the striking anger in his heart until there is nothing left but death.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

“imagine caring so much about fiction” imagine being so lame that you scoff at the timeless human practice of falling in love with art and stories

93K notes

·

View notes

Text

My friend wanted me to do this trend so here we go this book broke me

210 notes

·

View notes