Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Re-Weaving an Indian textile from Artek

The idea of re-weaving a fabric from the collection of the Alvar Aalto Foundation first hit me when I was visiting the Foundation’s furniture collection in 2020. I had been working, at that point, closely with the Foundation for a while, and also researching Artek and Aalto textiles for a long time, but somehow I had not arrived earlier to the conclusion that I could marry my theoretical insight to my developing weaving practice.

With my delight, the idea was well received by the Foundation, whose curators asked me to inspect a cushion coming from the Experimental House in Muuratsalo [Jyväskylä, Finland], that Alvar and Elissa Aalto had designed and built between 1952-54 as their summer residency, and as a project to develop an intimate architecture research centre on the shores of lake Päjiänne.

The cushion belonged to a rattan chaise-longue in two parts – seat and ottoman – designed by Alvar’s first wife and Artek founder Aino Aalto. The element I had to work on consisted in the padding for the ottoman part. It was threadbare on one side in the middle section and, as the house is open for visitors in the summer, curators wished to attempt substituting it with a reproduction.

The textile turned out to be an Indian plain-weave cotton fabric, belonging to the selection that Artek marketed between the 1960s-70s. Designer Sinikka Killinen had been traveling to the weaving mill in India – Commonwealth Trust Ltd. [Calicut, Kerala] – and had designed some textiles for Artek on location. This was possibly inspired by a 1965 display at Artek of textiles by Sheila Hicks, that she had created while working for Commonwealth Trust. Artek marketed both Killinen’s designs, as well as the producer’s own catalogue fabrics, to which the one I was dealing with belonged. Exhibitions of these textiles had been taking place at Artek in 1970 and 1976, the latter involving performative weaving by invited Indian weavers in the Artek shop, for the visitors to witness.

I started approaching the textile in what would be a discovering process for me, because it was the first time I embarked on such a project. I started by counting the thread density in the warp, which was 24 per millimetre, and sitting with a pantone catalogue, trying to match each coloured thread to the corresponding shade. I did so using the small bits of torn yarn sticking out in the threadbare section, in order to not have the colours distorted by the interaction with the weft, which was a bright emerald green. The weft was composed of a repeating pattern of four stripes of different width: three shades of blue and black.

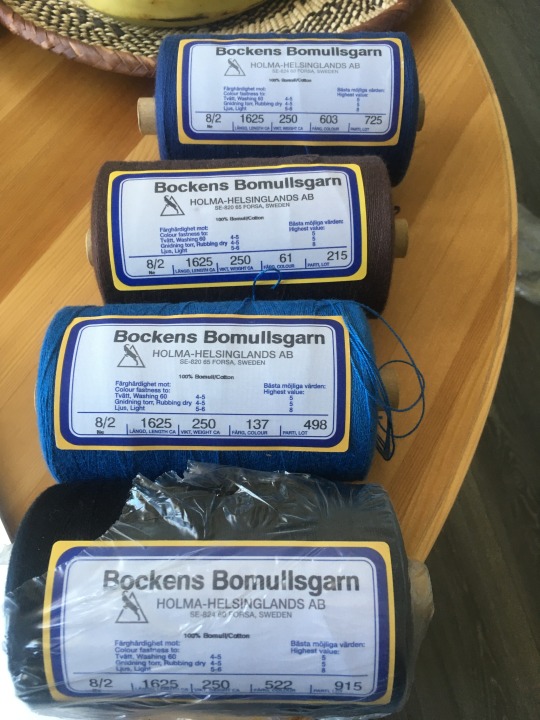

I tried then to retrieve similar yarns, both by visiting yarn shops and checking leftover yarns on sale in different contexts, and by referring to the catalogue of yarns available in Finland. I managed, in the end, to match almost all the colours quite closely by recurring to Bockens Bomullsgarn yarn: Ne 8/2, Tex 74x2 for the warp [colours 603, 137, 522] and Ne 16/2, Tex 36x2 for the weft [colour 3060].

There was only one colour I could not match: the lighter shade of blue. After some research and pondering I found some crochet cotton yarn from Esito [Ne 8/4, Tex 74x4, colour: 9051] which was way bigger than the size I needed, but that I could try to divide in smaller sections: extracting the four individual yarns twisted into the bigger size. This was a solution whose implications I did not entirely grasp: the fact that it would be extremely time consuming, and that the yarn would have been very fragile and difficult to work with.

However, the end result was the one I had hoped: the final yarn had the right size and colour! In order to obtain it, I twice divided the original yarn by rolling the yarns, as I was splitting them, on a cardboard cylinder. After I obtained the right size, I had to spin it again in order to attempt making it a bit more resistant, which I did by using a spindle – as I don’t have a wheel. After this process, which required some trial-and-error, I had to steam the small resulting yarn balls, to lock the yarn in its twist and avoid the warp yarns knotting themselves with each other as soon as they were left with no tension during the dressing of the loom.

Finally, I was ready to wind the warp! I first tried to create a smaller sample, to test my own process with reproducing the fabric, and to gain feedback from the Aalto Foundation before engaging with the bigger-size weaving. Results for the sample were satisfying – except for the light-blue yarn, that made it clear it needed to be dealt with very carefully – and the sample come out resembling quite closely the original.

I then started approaching the full-size reproduction, and wound a tree-meter long warp, for a final product that had to be two meters long and about seventy centimetres wide. I wound the warp in two sections, and then started dressing the loom. Once the warp was ready, I got going with weaving! The weft consisted of two threads of green yarn at once. Throughout the process I had to be careful to keep the warp quite humid, to try to minimize snaps in the light-blue yarns, which ended up happening anyhow several times, though probably not as much as I feared.

The warp was also so dense that it did not open very easily, as the small loom I was using could not provide a strong enough pull. I had, thus, to help the opening with my fingers, pretty much throughout the process, which made it quite slow, but also ended up making me interact very closely with the textile, and allowed me to control the fragile warp constantly.

Eventually, the weaving process proceeded rather smoothly, and I decided to deal with the broken light-blue threads by embroidering them into the fabric afterwards, as they were not so many, and the yarn was too problematic to add additional threads in correspondence to the broken ones during the weaving process. This ended up working quite well, with the final result managing to look like a finite fabric. Of course the ends of the broken and added threads still stuck out on one side of the fabric, but this did not matter, because It was going to be used as upholstery anyway.

I was quite satisfied with the final result, which looked quite well, and had managed to reproduce the pattern of the original quite closely. The colour, in the end, ended up being slightly different that the original, more so compared to the sample I had woven. This was unexpected, but I came to the conclusion that perhaps the very dense warp had packed the weft very tightly in, and thus the green note was less evident. This had perhaps happened slightly less in the sample, which consisted of a narrower warp. At the same time, the original had been used on the outside – as the chaise longue was often placed in the patio of the Experimental House – for perhaps six decades, and had received a great amount of sunlight, that had undoubtedly made the colours fade partly away.

In the end, the result was very appreciated by the Foundation’s curators, and with my delight the textile has been used for its intended purpose, and now sits in Alvar and Elissa Aalto’s intimate architectural masterpiece in Muuratsalo. For me, this was a very interesting process into understanding more deeply textile making, and reflecting on the presence of Indian textiles within Artek and Aalto interiors.

The slightly uneven quality of the original, as well as its fascinating alternation of nuances, was undoubtedly what made this fabric so interesting to the designers and architects who chose it. Aalto and Artek spaces have always been characterized by functionality in its elements, a very sensitive attention to materiality and surface rendition, and a wide representation of multicultural references embedded in a pondered selection of high-quality design products.

This fabric represented all this. Dealing with the very high density of the warp was a very direct experience of the great resistance that the finite product had, which made it perfect as an upholstery textile. Spinning and steaming the yarn also turned out to be a way to approach the slightly imperfect, lively quality that the original yarn had, and that emphasized the materiality of the textile surface. The Indian provenance of the textile, finally, was an input into researching more its history, and diving into the presence of these fabrics within Artek, connecting them to my earlier research and reflections on the recontextualization of non-western textiles within European interior design and Modernism.

[My thanks to the curators of the Alvar Aalto Foundation for making this project possible, and to Aoi Yoshizawa and Rosa Tolnov-Clausen for the feedback and support throughout this process]

5 notes

·

View notes