Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Challenges and Successes of the Shemitah Sabbatical Year

Click here to see the original Shemitah nigun I recorded with friends in Ngor

An extra layer of my sabbatical year in Senegal was the connection to the Shemitah year of the Jewish calendar. Truthfully, I hadn’t known my sabbatical year would fall along a four thousand year old count of seventh year rest and repose! I only learned about it when saying goodbye to a Jewish friend in Colorado. It was one of the most serendipitous happenings in a year full of them. Although the original commandment was directed towards farmers (read: almost everyone 4,000 years ago) letting their fields lie fallow, there were also rules of debt forgiveness, of letting gleaners work through your fields, of replenishing yourself.

Though COVID sapped my enthusiasm for virtual events and cocktail hours, I loved the mostly Jewish community I connected with online around our interpretations of the Shemitah year. I didn’t meet anyone uprooting themselves in quite the same way Carolyn and I were, but heard from dozens of people about seeing where in their lives they could step back, offer themselves the gift of repose.

It was a timely question for someone used to doing many things at once. Would Shemitah for me mean doing less? Not trying these new activities? More…meditation? If I kept my life just as busy but only changed continents and language, was I really honoring the Shemitah spirit? The questions were challenging, and fortunately, wrestling with thorny questions open to interpretation is an old Jewish pastime. It’s one of my favorite bits of cultural heritage.

I concluded that a full life is not the same as a busy one, though they can overlap. If my activities here were intentional and most importantly fulfilling, they were still in line with the ideals of the Shemitah year. The repose, as it turned out, would be from the parts of myself I stepped back from, to make room for trying out new pieces. For the first time in many years, I wasn’t seen as an educator, or an activist. Both of those pieces and the communities around them were more core to how I felt about myself than I thought. When I took them away, and the new facets I was trying -surfer, artist, writer- were still in their nascent stages, I had some lengthy stretches of…I don’t even know what to call it. Ego death? Dissociation? Identity drift? I stepped away from the pieces that I drew value from, and there was nothing yet to take their place. Even the identity of language learner didn’t hold, here in this place where studying French only made some people ask why I bothered to live here if I wasn’t learning Wolof. After the honeymoon period of the first few months in Senegal wore off, it felt the opposite of restful. I just felt…clumsy, and incompetent, and unseen, here in this sunny paradise where I had all the time to create my perfect world. It was never true all the time, and every day continued to have sparkling moments on the water, with friends or typing away at new worlds. Still, finding contentment this year even when I held all the cards was more challenging than I thought. Turns out, my perfect world has more stable community in it, more shared goals and projects, and those take time to create. I worked myself out of the identity hole, which continued to pop up in low moments throughout the year. I think of it now as the price of growth.

I really did make strides in claiming new identities as an artist and a writer, and built relationships that centered on those pieces. It feels more legitimate to claim them now, and that they rest with their green new shoots alongside the older ones. Educator, activist, those ones that will come back when I step again into my American life. I didn’t see it at first, the connection to depleted earth. The analogy really clicked for me more with a garden. But having stepped back, I’ve begun thinking about any identity that you lean on too long, too fully as a mono-crop, some squash or gourd that chokes out your other sustenance. Carolyn and I have already started talking about our next Shemitah cycle in another seven years. I’m grateful beyond belief that my partner loves the idea and timeframe as much as I do. I’m grateful that we have the privilege of jobs and stability that allow us to conceive and execute a year like this. In my own organizing work I hope to keep pushing unions and employers towards contracts and agreements that allow everything the time and space for new experiences. We’ve talked about learning music as a language, studying and practicing with the same intensity and immersion, maybe in Cuba. We’ll start to save money again this next year, a little every month. We’ll probably have young children. I hope the ancient practice of Shemitah will have even more adherents by then.

0 notes

Photo

Reflections on Language Studies in Senegal, French and Otherwise

In Senegal, I took French classes for five months, three hours a day for five days a week. That’s about 220 hours, total. Carolyn and I shared the classes with two different tutors who came on different days of the week. Those of you who know me know how much time and energy I’ve put into language learning this past decade, and my recent struggles with learning Arabic. Especially just coming off four months in Egypt, my language learning brain was in a strange place when I moved to Senegal in September 2021. On the one hand, French seemed deliriously easy next to Arabic. Yes, there were new sounds, and of course the spelling is laughably complicated, with vowel triplets clustered together. Still, the alphabet was familiar, verb conjugations took a familiar form, sentence order was more or less familiar, and there were lots of cognates.

On the other hand, I found myself struggling more than I ever had with just the motivation to learn. Part of it was the multi-lingual society we were suddenly living in. Though there are many languages spoken in Senegal -Pular, Mandingue, Djiola, Serer- the main local language in Dakar is Wolof. Most of my elder and younger neighbors spoke almost exclusively Wolof, or very limited French. Those are usually some of my favorite people to talk with and hear stories from, the very old and very young. It was not a structure conducive to creating a Franco-phile. I was dually thinking, “Come on, I just almost broke my brain learning arguably the most difficult language in the world!” and “even if I do learn French, my neighbors just want to speak in Wolof anyway!” There was also at least three structures working in my favor to learn French, and so eventually I did. One was the fact that though French was less useful in my neighborhood than I’d hoped, English was even less useful. There were very few Americans or English here, besides tourists going to Goree Island, and in all my many conversations of folks guessing my origin, no one EVER guessed I was American. I could count on one hand the number of people in the neighborhood who spoke conversational English. So, French it was.

The other factor was just the structure of having language courses every day, which I’ve found is an essential part of my own language learning. If you’re not learning from professional necessity, or romantic interest, but intellectual curiosity, better hire a language teacher. My tutors were friendly and decent teachers for the most part, but just the repetition and presence in front of me over those months built up the base. The final piece was having an accountability partner in Carolyn. I was worried about how we’d fare in class together, both bossy students, but generally we brought out the best in each other’s French learning commitment. It was a bit of tortoise and the hare dynamic. I was the lazier language student for sure, and over time Carolyn’s many late night dance conversations with French speaking friends and constant reading of Harry Potter in French paid off.

With friends from France, I still get lost. The accent and jargon is hard to follow, although I can hold my own in conversations. My Senegalese friends tend to speak a bit slower, and the vocabulary is more familiar. When I stopped taking language courses, writing down new words etc, I plateaued big time. Some new phrases forced their way in through sheer repetition, but the French-language Michael Crichton novel I bought sat unread on the shelf. And that’s okay. I feel comfortable speaking with friends, getting around, reading and writing messages.

Truthfully, I still hold some guilt over prioritizing the colonized language instead of the local one. After I could offer greetings, thanks in Wolof, ask after health and family I stopped actively learning. “You show your respect for the culture through the language” had always served as a guidepost in the other places I’d lived, and here I wasn’t following that logic. Slowing down to spend time with neighbors, even if it was non-verbal, connecting through singing and sports on the beach, spreading out my business with shopkeepers in the village, keeping a long, long list of names and pronunciations in my phone, those were ways I tried to make up for what I lacked in Wolof-speaking capabilities. If we’re not careful in acknowledging our long-term goals when we meet them, the posts just keep on moving. If I’d done it over, I would have tried not to be so hard on myself for focussing on French instead of Wolof. Idealism battles practicality. By most metrics that matter, I can speak French now, and that’s a huge celebration. I’m excited to connect with the West African French speaking community back in Aurora. A bientôt.

0 notes

Video

tumblr

Reflections on Surfing in Senegal

I started learning French and surfing at about the same time, right when I first arrived in Senegal. Now, at the end of my sabbatical year, I think that I can safely say I’ve progressed much farther in French, but had a blast in the water the whole time. I spent a lot of time surfing this year, usually at least four times a week. It was how I first arrived in Senegal, spending two weeks at the Ngor Surf Camp as a soft landing. I’d tried a few times before, once in Oregon and twice in Mexico, but never with a serious learners mindset. I know swimming calmed me, though. I thought it might be like hiking and rock climbing. I thought hiking was as good as it gets in the mountains, and then I saw people hiking on their way to do something that seemed even more fun; rock climbing. I’d been lap swimming for years as a post work de stressor, and surfing seemed even more fun! Now, I lived a 10 minute bike ride from three excellent surfing spots, and if there was ever a time to learn it was now.

For better or worse I made constant comparisons to rock climbing. There was the same flow state when fast, continuous movement was required, that if you thought you were going to fall then you would fall. There was the idea of individual sport, that if you didn’t do the thing you weren’t letting anyone else down, and it was up to you to have a positive attitude about the whole affair. There was the desire for space, that you might groan rounding the corner and seeing a crowded crag the same as a crowded wave lineup. There was the obvious comparison of danger. (I bought a padded surf helmet and rubber soled water shoes my first week and silently blessed them every time I saw a bleeding head or foot full of urchin spines). In both sports, rocks would bash you up if you weren’t careful with where and how you fell. And you would fall. Over and over and over again.

In other ways, though, it was a unique athletic experience, and a cultural one too. It was solo, for one thing. You didn’t need a partner, and though it was almost always more fun to surf with friends it wasn’t necessary. Almost no one besides the surf schools were out in the morning, and I didn’t want to wait until other friends got off work, so for the most part my surfing was a solo affair. 95% of the time there would be others in the water, and we’d nod to each other or chat, but we were in our own worlds, on our own boards, sometimes jockeying for the same wave. “The Lineup” was an unwelcome change from climbing, this idea that you wait your turn in a conveyor belt for a wave to take. True, sometimes you have to wait at a crowded crag, but when it’s your turn the rock wave is all yours, and you take as much time as you want. I was spoiled surfing here, with rarely a crowded lineup unless I went with friends on the weekend, but I heard lots of horror stories about California surf breaks. The local surf community wasn’t so big, and it was nice to see the same faces over time, be recognized in turn.

The sensation when you do take a wave makes it all worthwhile, the cloud-floating. It feels like powder skiing, similar enough that I imagined I already knew the sensation, but I enjoy catching a good surf wave so much more. Maybe because at my skill level I frequently miss waves, paddling too late or nosediving into the washing machine churn, when I do catch them the thrill is magnified by some mix of relief and pride.

Surfing in Senegal is also a cultural experience, where the almost exclusively European tourist are taught and wildly outsurfed by local Lebou surfers from fisherman families. I’ve heard from neighbors that it’s looked down upon by some of the older fisherman, these kids just playing in the waves where they make their livelihood, but that’s slowly changing as those kids grow up as instructors earning their own livelihood. The kids, too, are magnificent, little wiry whip-saws with more muscle memory already for surfing than I will ever have, carving up and down wave faces on tiny boards. There are two wonderful groups that help out Senegalese kids with boards and training, one based with Marta and Aziz at Malika Surf Camp in Yoff, the other with Pape in Secret Spot. On Wednesdays and Sundays in Ngor Beach free lessons and surfboards were handed out. Watch out, European surfing world. Senegalese kids are incredible athletes, goofballs, unafraid to look silly and willing to try anything.

I was wary of scowling surf egos, but those come almost entirely from the Europeans. Even the few Senegalese surfers who are less than warm towards me on land smile more in the water. I’ve seen it bother European visitors that the concept of the lineup and wave order here seems loose. People in the middle of the lineup with paddle for a wave, and sometimes multiple people will share a wave. On the bigger breaks, more advanced surfers will chance the bigger waves closer to the break for a chance at priority and a longer ride. “They’ll take your wave, here,” one Australian surfer told me, “But they’ll do it with a smile.”

I loved almost every surf session, and worked hard to keep a beginner’s mindset, a sense of humor when I didn’t progress as fast as I thought. By the end, I could catch most smaller waves under good conditions -say, 2-4 feet, which seems way bigger when you’re lying flat on the water- and have a blast doing it. I don’t know that I’d chase it all over the world, or that I’m interested in working to surf even bigger waves. When rock climbing is the sport de jour back in Colorado, I think I’ll be just as content to switch back. Still, I imagine some time next winter, shivering, I’ll imagine riding a rolling wave all the way into shore.

0 notes

Photo

My Writing Project

I had a lot of goals for my sabbatical year, but the one that might have taken the most time was unplanned. Looking back through my journal, I had wondered that first week how I would fill my time besides surfing, learning French and hanging with friends. Would it be diving into painting goals more deeply? Music? A quick note in my phone’s "Project Ideas” list from September and one clear image set the faint cornerstone, although I didn’t realie it at the time. Nine months later, these three first draft manuscripts sit on my desktop. It still doesn't seem real. I’ve had the goal of writing a book for a long time, since first grade at least. Now, I'm closer than ever, though nervous with my sabbatical year coming to an end how I'll advance forward.

The image I started with was Colombus’ little fleet landing in North America. Arriving, they meet a fully mobilized tribal army armed with gunpowder and resistance to European diseases. How different history might have been. That was the image I imagined the book closing with, and spinning back from there led to this ambitious project. One book become two became four. Once the core of the story came out it never changed, but there was just too much that needed to happen, too many little tales to fit inside.

I don’t want to say too much here about the story itself, though I hope anyone reading this post will also read the books. If I had to pitch the story in Hollywood I’d say Moana meets Mad Max meets Guns, Germs and Steel. If I had to pitch it in a blurb I’d say “A group of navigators in the 15th century chase a vision across the ancient world, diffusing new ideas and technology, changing the course of history and challenging their own beliefs and identities in the process.”

The first push was NaNoWriMo, the National November Writing Challenge, which I’d heard about for a few years. 1,500 words a day for a month gets you around 50,000 words, enough for a short novel or most of a longer one. I gave myself the challenge of writing a few different short stories in October, and fleshing out my original idea the month before. The most productive I’d ever been was in creative writing classes at the university, pacing around the campus at night and returning back to bang out prose I’d later edit. If I had a smartphone then, in 2012, it certainly didn’t have the lures of my little pocket portal today. Leaving it at home (and leaving home) during morning writing sessions made a world of difference.

There is so much research that’s gone into getting the details of pre-European contact life just right. I’m leaning heavily on my alumni access to the JStor scholarly database, and I am definitely going to outsource the works cited writing. Old maps, details of rival city-state clothing and regional food during specific times of the year, original names for constellations from neighboring tribes…there’s a lot. I’m glad I started without consulting anyone, because I might have been talked out of it, and now I’m in too deep to stop. It’s been intellectually fascinating, and also tough and often lonely. No one should ever boo-hoo the writer privileged enough to spend time on a *bonus* pursuit. Our discomfort is entirely self inflicted. Still, where our early human storytellers spun out myths exclusively in groups, the written word demands solitude at first. It’s only later that you see how people have received your creation. That never quite registered with me, spending a night or two writing short fiction in college. Now that I’ve spent hundreds of hours creating worlds no one has yet seen, with characters who seem as real as my friends, who in this last book I feel like I’ll be following more than writing, I appreciate those creative souls who came before me. Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, One Hundred Years of Solitude. Just single people hunched over a writing desk, pecking away.

My goal is to finish the first draft by summer 2023. Hopefully this next winter I’ll have the chance to travel to the Marshall Islands in Micronesia where much of the first book takes place, and add to my research with real faces and names and smells. I’ve lived in many of the places I’m writing about, but doing justice to the cultures not my own requires incredible care. I want to get the details right, and my hope is to partner with cultural organizations for a first look sensitivity read on related parts of the books.

There’s also the fear of spending so much time working on something…that might not be very good. The story might feel overstuffed. The writing might feel flat. My attempts to bring complex characters from different backgrounds might read as gimmicky. Writing gorgeous prose in addition to a compelling story is so tough! Young adult writers have it easier; the bar is significantly lower. I’ve been working to try and root my definition of success in just bringing this to completion. To be sure, I’m going to iterate the hell out of it, but I don’t know if I’ll ever be satisfied with the final result as it sits in my head now. I have to be okay with that.

0 notes

Photo

The Cast of Characters

“The soul of a country lives in any one block” -Peter Hessler

The people make the place, and that’s especially true in Dakar. Besides the painted pirogues in Lebou villages, the bustling downtown markets and -gulp- the remaining French colonial architecture, Dakar is not a very Instagram ready city. “Lots to do, nothing to see,” is how someone described it to me. It’s a magical and compelling place because of the density and full commitment of it’s inhabitants to living their lives out in public space, and often together. Men work out in the dozens on the beach in muscled groups, women stride together in neon tailored dresses down the street, the nightclubs are filled with coordinated Afro-beat dancers, kids run squealing in neighborhood bunches down the alley, the fisherman grunt and haul their vessels together out to see, vendors cluster together with hair products and mangoes and dried fish. It was so overwhelming, at first, that it took a minute to separate out faces and stories from the crowd. Some of my first attempts at friendship didn’t quite take, as happens in anyplace. Here are snapshots of some of my favorite Senegalese and West African friends I spent time with this year:

-Ibraham: Guinean musician with a spider tattoo on his shoulder (he told me the spider protected the prophet Muhammed by weaving a web across the entrance to a cave where he was hiding, leading his pursuers to think it was abandoned.) I met him trying to haul heavy new flower pots up my stairs, when he stopped to lend a hand. He’d lived in Dakar for about 8 years, came looking for work and learned Wolof from kids here, though he spoke a half dozen other languages besides. He was an incredible musician, especially percussion, with a whole stable of guinean songs he could lead solo or sing as part of a group. I eventually started taking drumming lessons with him in the spring. He was constantly meeting new arrivals -especially from Guinea- and taking them under his wing, as well as striking up conversations with friendly foreigners. People were drawn to him, I could see. It was also a tough year for him, precarious housing and economic situation. COVID hit everywhere hard, especially creative industries that depended on live performance, and Senegal was no exception. He battled some dark days, alternating between seeking work in low-skill labor fields and holding out for musical gigs that never materialized. There was always his family home in Guinea to go back to, and at the end of my time he was ready to head home and recharge if things didn’t improve in a few months.

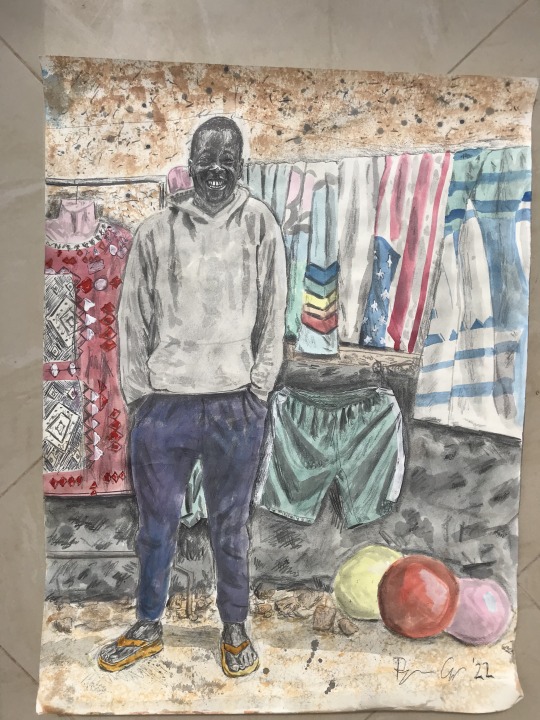

-Abdalla: I drew a portrait of Abdalla for his mom, and I needed to erase the mouth twice to make the smile bigger each time. That should tell you most of what you need to know. I had trouble connecting with a lot of the Baye Fall besides occasional greetings, but Abdalla was a local boy who seemed to dip his toe in just enough to scoop out reggae music and an extra dose of peace and love. The songs he composed himself are some of my favorite pieces of music from Senegal, and I hope he has the chance sometime to sing them in front of the huge crowd he deserves. His mom -Madame Faye- was not only acknowledged as making some of the best thieb in the village, but gave some of the best life advice around- I spent a good few days in her kitchen, where we’d berate Abdalla together for not helping with the cooking and he’d laugh his big laugh and play us another song. He was trying to organize a local music festival through the town, and waiting for enough funding to record an album. I worried about how trusting he was, sometimes; he always took people at face value. In the winter he let a new arrival looking for work sleep in his bed, and the man took off at 4 AM with his recording instrument, phone and guitar. The village seemed to take care of it’s own, though, the tough fisherman always jostling him affectionately when we walked around. He led a lot of our song circles, parceling out melodies and crooning high notes. During one golden afternoon I walked out to the beach and swam to Ngor Island, to find Abdalla on my favorite hidden beach with a few friends. They had guitars, flutes, drums. We sang together, and then when the sunset came we hugged and I swam home.

-Nalla: Friends who work towards goals are high on my list, whatever those goals. I few years ago Nalla was a pastry chef, when he decided he wanted to pursue art. He spent most of his time on the island, helpings uncle fix up a giant dilapidated house they were going to one day turn into a hotel/restaurant. There he holed up with paints and scraps of wood and canvasses and worked on his technique all year. Soft-spoken, blue-black skin, the chiseled Lebou cheekbones. He was one of the most constant presences at the Tuesday art nights, and I saw his technique improve dramatically while we were there. At the end of the year, he had a piece entered into the Dakar Biennial, and I felt like a proud cousin. He was an Ngorois through and through, with his dad a fisherman and dad an underwater welder. It was astonishing how may people he said hi to, both in the village and on the island. Sometimes we’d take out kayaks from the house, paddling out the the surf wave and daring each other to take bigger rides in the hard top. Even in the water, he knew every fishing boat and solitary figure that slippered along with a spear gun. He was focussed on bettering his art with a laser focus, to the exclusion of looking for a romantic partner, trying to stay on the island so he wouldn’t get distracted.

Julie: My Congolese friend, with a big smile and a weakness for sappy French love songs. She’d lived here for a few years, but been in a toxic relationship that she’d just escaped a few months before we met, with a jealous partner who didn’t want her to leave the house much. She talked about her mom often, a professional chef who cooked for airline pilots at the flight lounge. (Incidentally, her chicken recipe is one of my most treasured phone notes from my time there) When we met she was managing a clothing boutique, and sparring with an owner who seemed both not to trust her enough and to ask for too much commitment. It was fun to be around her; she had she energy of just having moved to the city and wanting to try everything. Carolyn took her along on several dance nights, and I think she might be hooked. Notably, she has an identical twin named Juliet, and two gorgeous twins with almost the same name caused a stir whenever I saw the two of them out together. In some ways she seemed to be adapting to life in Senegal, and others still seemed to grate. Taxi drivers going for the financial jugular in proposing fares never stopped annoying her. I’d long since resigned myself to giving the many kids asking for money a sympathetic smile and walking on, but it made her angry to see every time. “What parent would let their child out to do this??” She’d always ask. We were both trying to make friends and community in the new city, and reconcile it’s patterns with what we were familiar with. It was so nice to have a partner in that.

Petit: I first saw Petit marching around at midnight acting like a tree come to life. He was acting out a scene on the dance floor with his friend Tafa. The two of them remain some of the most creative individuals I’ve come across in any country. Like athletes slumped over chairs except for the big game, they had the ability to hide in a crowd, or to dazzle. Petit was often out of town, down performing or taking workshops down the coast in Toubab Diallo, but when he was around I loved getting together to dance or just play with movement. He had recently taken a puppet making course as well as a mask-styling workshop, and also worked as an acting teacher for a local school. He grew up in the southern region of Casamance, and talked about it always with deep, abiding love. I have no doubt when I go back he will be living there. His projects dealt often with the relationship between the self and the whole, or past traumas unearthed and confronted. One night he extemporized over Ibrahim’s drum beat, a monologue on the contentment we feel or don’t when alone. The last week before I left he was preparing a dance to welcome a group of black Americans, part of a program called Back to the Source. They were traveling to the famous Door of No Return on Goree Island, where slaves where loaded onto ships. After, they'd come to Ngor, where Petit and his crew were constructing a beautiful wooden door, through which they'd dance their American cousins as a blazing contrast to the door on Goree they’d just “closed.” Having such bright creative energy was a blessing and a half this year.

-Cheikh: ran a clothing boutique near the beach. He invested a lot in upgrading the space while I was there, until it became the hang-out spot for his group of friends. Twenty years ago he started out just selling clothes from a bag on this beach, and it was cool to see him now with a fancy shop. He started selling ice cream near the end, which I thought was a smart business move. I set him up with a Tinder account and we talked about love and dating a lot. His friend Moustafa always had a good sense of the political goings on of the neighborhood, and I lived leaning against the clothing racks, picking their brain and occasionally helping them sell things to tourists or lay out new merchandise.

-Amadou: Worked at a French-Senegalese organization around the corner, a center for unhoused kids, often running away from Quranic schools or home. Amadou ran soccer programs for them, helped with the lunch programs and literacy courses. He was a formidable soccer player himself, chiseled straight out of a men's health magazine. I couldn't believe he was still single. It was a treat watching the African Cup with him, such intense concentration and joy.

And many, many others of course, too many to fit here, everyone on their path, with lovely traits and foibles and disappointments and dreams little and big.

My European and American friends are dear as well, and just because I don’t spin out their stories here doesn’t mean they didn’t make this year so very special. Ben, Nick, Emily, Sait, Anne, Sara, Liz, Jake, if you’re reading this, sending you a big hug.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

The Sound of Music in Dakar

Note: Tumblr only lets you post one video at a time, another reason people are leaving in droves. There are too many videos to choose from, here’s just one from one of my last nights hosting a jam session on our terrace.

In different places I've lived, different senses store more memory than others. In Chengdu it was smell, hot pepper oil and frying scallions and mashed ginger. In Cercedilla, Spain it was sight, the roots and cobblestones meshed together on the old Roman paths, the valley vistas above Siete Picos and the low shrubs that hid sleeping cattle. Here in Dakar, my strongest sense-memories are tied to sound.

Some of it is city noise. I hear the barkers yelling out destinations from the back of shared busses, plinking on the back with a coin to signal the driver to stop. I hear the jingle on the harnesses of horse carts as they weave around people and cars to deliver loads of rebar or concrete to construction sites. I hear endless neighborhood games of soccer, and the grunt and swish of wrestlers in sand on the beach, and the scared but excited peals of laughter of women carried protesting into the water by bulky partners.

The most lasting sounds, though, are musical. There is always a beat in the background, always a melody. There is no elevator music here; even the supermarkets seem to have an expert DJ spinning Afrotracks in the booth. The nightly Sufi chanting circles gave me prickles of future nostalgia even as I heard them for the first time. Most of all, there are the drums. Odds are, somewhere in Ngor, most days, there is a wedding, nup ceremony, or naming day. That means a circle of drums and the leader, a local public drumline, rat-tat-tat, the stretched animal skin booming out from across the square. I could well imagine them using the giant signal drums I’ve seen in Casamance to communicate between villages.

It was impossible not to hear the drums and the think that somewhere down below, people were gathering in their best to celebrate the rituals of life. That there was a good chance I would run into these gathering walking back at night made it all the better, a permanent open invitation to wedding crashing, to join the spectator circle and just be. I never took videos -they were expressly forbidden at the healing ceremonies, and the rest of the time it felt othering- but these words will be enough to conjure them back.

Maybe even more than the adult drumlines, I loved watching kids practice. Using old plastic jerrycans or upturned pots, they would get together just like the bigs, older kids leading the younger ones. It wasn’t a hodgepodge, either. They would choose a rhythm and iterate on it. When I was younger I imagine I played dress-up. We all play at the adult world. When five year old are tapping out polyrhythms on the beach from inside the hulls of giant fishing boats, you know the bones of tradition are being passed down well.

For the first time, I can include my music in the sounds of the city. It took a little while to feel like my talented musician friends were not just doing me a favor by letting me sing and improvise along with them. The nigun singing circle I’d been a part of in Colorado gave just enough confidence to try. Whether plinking a metal pipe or scatting a high vocal over Abdalla’s guitar riff, jam sessions with friends around the neighborhood are some of my dearest memories. I had no ability to improvise with guitar or drums (and still don’t although I would like to), but vocalizations were different. Playing music together is a more democratic activity in Senegal, a lower barrier to entry. Daring myself to try and love it, to be a part of the jam session and not just an observer is a gift I’ll take back with me. I thought a lot this year about my own relationship with drumming. I loved hearing rock and roll drum solos, but also rolled my eyes at the white hippies in Boulder chanting out with their big African drums. My mind screamed cultural appropriation, that it was cringy and wrong. Was it just in my head?

Researching traditional Jewish drumming helped. Our people used mostly hand drums, “the Miriam drum,” a light tap-tap as opposed to a larger djembe or some such. Still, we stretched our animal hides over the top hoop, and danced. There was no snare drum then, no base. The same with Celtic drums, or Nordic, or Roman. White people have drumming in our roots too, though I feel divorced from comfort with the original instruments. Rock and roll, electronic dance music, all these pulsing, thrumming beats. We’ve had it all along. Is it not better to acknowledge the source?

Live music was everywhere. Our neighbors played, our friends played, we played, and went to several concerts. A few notables:

-Sona Jobarteh, Gambian professional kora player, the only woman with such a title. She comes from a traditional griot singer-storyteller family, and performed with her son and others at the French Institute in Dakar. She was a queen, enthralling, generous and also indisputably in command. The sound of the kora is like the harp, and from experience ai can tell you incredibly difficult to play

-Orchestra Baobab: I saw them perform twice, one of the original “Afro-jazz” sounds from Senegal to gain international recognition. They were originally the in-house band for one of the downtown hotels in the 1960’s, and the children of several original members still played with the band. They sang me “happy birthday Ryan” when I saw them in March at my neighborhood bar-resto, and I could have keeled over right then from happiness

-Burna Boy: The Nigerian wunderkind. The concert was an experience, albeit not entirely a positive one. Even in a land of loose time, this stood out. Doors opened at 7 PM downtown at the Grand Theatre, I got there at 10:30 PM, and Burna Boy didn’t go on till…wait for it…3 AM. Around 11 they started showing what I assumed was a music video of him on an airplane, until someone told me no, they were livestreaming his private flight from Nigeria. He hadn’t even left yet. Hubris. I was so tired and frustrated I left after two songs when he finally came on, but the songs are so infectious I can’t stop! I heard he was on time when he performed at Madison Square Garden last month, and it made me respect him a little less, but I will still always think of “Ye” as a track of this year

-Youssou Ndor: Maybe the most famous Senegalese musician. I watched a documentary about him before I ever came to Senegal, and jumped on the chance to see him at the Grand Theatre. It was like Touba all over again, the most elaborate outfits I had seen in the city, a private Dakar fashion week. It was worth the tickets just to people watch. He started around midnight, and I’d been warned about his legendary stamina. I also finally admitted to myself that while the mbalax music style he pioneered is something I can appreciate, it’s not a music that makes me watch to dance. There’s something about the mouse-heartbeat rhythm that doesn’t let my brain pause to hook onto a beat. The dance style is mesmerizing, frenetic movement of knees and elbows for a few seconds at a time. The dancers onstage were otherworldly. We left after a few hours, expecting the concert to go till dawn, and I’m still so glad I saw the icon.

0 notes

Photo

Scattered Adventures and Good Times

There’s nothing like having a routine to break. In between the rituals and activities anchoring me in my week, I wanted to capture some of the scattered memories and events across the year:

-My trip down to Toubab Dialow for Anne’s birthday, bachnalian night of dancing fresh juice by the beach, surfing at Pierre De Lys before it gets developed into an international shipping port and buries the wave -Visiting the new downtown mosque by HLM market with my friend Amdy Moustafa, being welcomed inside, discussing Islam and Judaism in the still unfinished courtyard.

-Hosting my mom and Carolyn’s parents in the springtime, seeing through their eyes all the pieces of the neighborhood we took as commonplace. Realizing from their baby-duckling movements how far we’d come in being able to navigate this new world.

-Eating lunch at Chez Hussein, the small restaurant next to the dirt soccer field with the best thieb in town (that you could buy at a restaurant). Since my mornings were unplugged and solo, it was always a treat to run into friends or Carolyn there on my way back home. It was the same cast of characters all year, an international West African mix of locals and professionals who spoke in a shifting mix of Wolof and French. Hussein’s wife cooked and he held court with questions on religion, politics, and the rest.

-Playing tennis on the beach with the heavy Senegalese wooden rackets. It was a goal of mine to improve this year, ever since the first week at Yoff where I saw men go back and forth like the Williams’ sisters. Senegalese friendliness meant I could always walk the 50 meters to the beach whenever I felt like playing -at any time of day- and find a willing partner. Nalla and I had a fun art day painting custom rackets, which I lugged back home

-Our trip to Israel for Ariella and Noam’s wedding! This came at the end of our time in Senegal, and maybe merits it’s own entry. First time for Carolyn, second time for me. It was a strange halfway experience, back in a more Westernized country that wasn’t the US. Once again, the Western Wall was an emotional experience, and I continue to have mixed feelings about supporting a state moving increasingly away from my values. After my time in Egypt and Senegal I felt so much more comfortable and culturally competent to engage with Arabic speakers there. A missed flight led to a surprise two day stay in Istanbul courtesy of the airline, and we weren’t complaining.

-Competitive Potluck: For almost eight years now, Carolyn and I have hosted a competitive potluck with friends, going back to the Golden Saltine in Idaho. It’s a lovely way to be praised for a meal you spend a lot of time preparing! Plus, who doesn’t want to win a trophy. With the addition of a French foodie (Dan) and trained German chef (Sara), the level of competition was higher than ever! We managed two sessions, the first a French tasting course that Dan swept with a pork-apple appetizer, the second a seafood themed dinner I won with a smoked oyster-mango treat. Food and friends, what better.

-Fabric shopping and clothing design: “Sweetie, the tailor called, would you head down for a second fitting this afternoon?” And other lines I never in a million years imagined myself saying, not unless my material circumstances changed dramatically. What can I say? When in Rome. Custom fashion is as affordable a commodity here as fish (seriously, a tailored dress and a 5 lb filet of sealife might both run you about $10). Senegalese tailors are wildly talented and inventive. It took a little while to find a tailor in the neighborhood I really liked, from the ten or so shops within 100 meters of our house, but once I did, Monsieur Bada Seck and I worked together for the rest of the year. He was endlessly patient with my alterations, and I grew more comfortable asking for designs I’d only imagined, not seen anywhere else. Wonder of wonders, I had at least two custom orders from other people who’d seen my designs and wanted their own! It’s a lifestyle I certainly won’t be able to afford back in the States, but bright, bold colors and designs that don’t scream “white dude in Africa” are something else I’d like to keep chasing back home.

0 notes

Photo

Snapshots of My Daily Life and Routines in Senegal

It took me a little while to settle into my rhythms, I’d say a good two months. Having routines that I can occasionally break is my happy place. Having taught for two stressful COVID years, the sudden freedom to arrange my days felt bizarre. I tried to never let the wonder die down, though we humans are just so freaking good at adjusting our baseline levels of happiness. Generally, many of my days would go like this:

Wake up, tea and stretching on the terrace, writing in my gratitude journal. Going downstairs, loading my surfboard on the bike rack, wheeling it out of the sandy alley and towards the parking lot. Saying hello to Bashir selling coffee, Nombu selling breakfast sandwiches, Abdalla opening his variety shop, Babacar selling sunglasses, Lamin idling his taxi. A ten minute bike ride to one of two shoreline spots, a bit on the paved road but mostly cobblestoned alleys and dirt streets. Construction piles, herds of animals and puddles changed overnight, so the route was always a bit different. If the tide was right and waves were good, I’d start out surfing, occasionally with a friend but usually hitting the water solo. There were almost always other surfers in the water, and if I didn’t get an early enough start one of the three surf schools would show up with a half dozen students. I rolled my eyes but up until the very end I’d classify myself firmly as a beginner.

Getting tossed around in the waves does wonders for the creative juices. Mostly it shook my mind blank, left a tabula rasa for writing. It’s the opposite feeling as when I finish a stretch of doom scrolling, that unpleasant sinking tunnel vision. After I dried, I’d head upstairs to the second floor of a surf shop and cafe. It looked out over the water, and was always perpetually under a bit of construction. The narrow staircase was hidden and the shop itself was set back from the main beachfront venue, so in my whole year there only a dozen or so people ever joined me there. It was the perfect writing spot, and with no phone or internet connection I could pace around with my small, over sugared cafe touba smelling of cloves, until I sat down to hit my daily word limit. Lunch was usually not ready in the shops until about 1 PM, so I could take my time getting back. Since I never brought my phone, lunch plans were serendipitous unless I’d organized something the night before. There were three little restaurants who made excellent versions of mustardy yassa, peanut tomato maffe and the Senegalese national dish, thieboudjiene (rice and fish). Often I’d run into Carolyn at one of the shops, or if I dropped my things off at home, we’d head there together.

In the afternoon we’d have French class, between which I’d sneak off for another workout, or playing on the beach. Intensive language learning is such cognitive exercise you’ve gotta do something to shake it up between classes. In the latter half of the year after French classes ended I’d replace it with a delicious siesta.

Nighttimes varied. Tuesday we’d host a weekly art night at our house, Fridays Shabbat, Thursdays date night with Carolyn out and about somewhere. On Wednesdays one of my friends MC’ed a little open mic show at a beach cafe nearby, where we’d laugh and dance and go outside to look at the waves when it got too hot. I met two of my best friends there, actors and dancers who came up with a new piece of performance art for the dance floor every week.

Candidly, nighttimes were also some of the more challenging for me. Carolyn had her dance community locked in at least three nights a week until the wee hours, but in my unplanned days I sometimes found it hard to motivate myself for a big night out, or even a walk around the village. It wasn’t for a lack of people available, but getting caught in a now familiar Ryan-trap of my own devising. I’d be conflicted about hanging out with American or European friends during my time in Senegal, but my Senegalese friends wouldn’t START their night until at least 11 PM or later, when I thought of getting up early to surf or write. If I could talk myself out of the non-issue I’d usually end up having a lovely time out, or if I could make peace with the slower pace of a sabbatical year have a lovely time staying in.

After the first month of shopping trips to the big markets, I rarely went downtown, and met a goal of almost exclusively getting around on my bike. Mostly that meant staying around the neighborhood, since Dakar is the opposite of a bike friendly city. I could bike ten minutes in either direction to a surfing/writing spot, or put on my wetsuit and swim to Ngor Island to see friends, or just walk to any of my usual haunts in NGor. It was a dreamy commute, and I’m sure as my life revs back up to normal American professional patterns next year, it will seem a dreamy routine.

0 notes

Photo

Senegalese Politics, National and Global

There was a half hour a week or so ago where most of my neighbors came outside around 8 PM to bang on pots and pans. I thought it was another wedding or healing ceremony at first, but it didn’t sound like the other drums I’d heard. Later, a friend told me it happened all over the city, a way to protest the president Macky Sall and his political party. Earlier, the president had issued a new order requiring authorization for political demonstrations of all kinds, and promptly denied one to the opposition party. Like a depressing number of countries in the world, Senegal is also seeing anti-democratic steps taken by the party in power.

After independence a scant 60 years ago, Senegal has had a constant love-hate relationship with France. If you ask the critics here -and there are many- France saw the writing on the wall and left without a violent fight, but still managed to continue it’s extractive legacy. The Senegalese elites were brought over and educated in France, and multi-national companies gained monopoly share market power. Today, the largest technology companies -Orange, Free, Wave- supermarkets -Utile, Auchan- and construction are all foreign owned, many French.

Like other places in mineral rich African countries, cobalt and other rare-earth minerals are being mined by other multi-national companies. I spent an afternoon with a Senegalese engineer musing about what the economy would look like with a national mining company controlling mineral tracts that dealt exclusively in a Senegalese currency. (Senegal uses the Central Franc African, which is minted and controlled by France.)

The influence of China’s Belt and Road campaign are everywhere, from a new national highway to a small water pipe project in Ngor Village. Equipment and road signs are written in both Chinese and French characters. Chinese engineers supervise Senegalese laborers as they dig ditches or weld bridge struts. In one case, I recognized a bridge design over an eight lane highway as the same type from when I lived in Chengdu. The Chinese themselves leave a light cultural footprint despite the economic clout. They mostly stay in a community outside the main city peninsula. There are only a few game parlors and restaurants with Mandarin characters downtown.

In Southern Senegal, Indian companies dominate the lucrative cashew markets, storing the raw nuts in huge warehouses and shipping them elsewhere for processing. (One of the products of the hard shells surrounding the cashew nut is used for jet fuel. I’ve seen how it explodes in the fire, and the corrosive juice is used for traditional scarification.)

I’ve been reading up on 15th century history for my book project, and in some ways it seems like so little has changed. Rapacious Western countries continue enriching their citizens (first it was Portugal), though now it’s more boardroom dominance than outright imperialism. China continues as indifferent merchant princes, and Islam allows a network of businesses stretching to the Middle East ease of business with religious kinship. (One exception to this is the tense relationship with the Senegalese-Lebanese community, who in some cases have been in the country for generations. A very successful business community, they nevertheless keep to themselves, and several Senegalese clothing vendors downtown have tried to steer me away from the Lebanese garment quarter and to their Senegalese “brothers” with the same clothing shops.) No one’s outright denying a Senegalese company from applying for mining permits, say, or manufacturing plants. But when other governments support their businesses in expanding, how is a Senegalese entrepreneur supposed to compete?

Against this whole backdrop, there’s lots of popular resentment against the President and his party for cozy economic deals with other countries at the expense of investing in local businesses. With elections coming in the next few years and the ruling party trying to kneecap opponents already, we’ll see what happens.

Ending on a bright note, this civics teacher was thrilled to see how seriously my Ngor neighbors took village elections when they were held in the fall. It shouldn’t be a surprise; until a generation ago everything was village politics, and the national ruling parties had no candidates. It was just the village chief. Now, though, my neighbors milled around at the nearest polling place, the school next to my house. The very things that Americans complain about on Election Days -long lines and having to wait, people coming up to bother them about this or that party- are a non-issue here. People are always waiting around for things anyway, and people are always coming up to sell you this or that. I found the whole atmosphere like a block party, and the former mayor -who was aligned with the President- was resoundingly voted out. My boxing coach was appointed commissioner of sanitation, and told lots of stories about the former budget disappearing into this or that pocket. At least in Ngor, my neighbors were ready for a change.

0 notes

Photo

Religion in Senegal

Having just moved here from Egypt, the ways Islam showed up in daily life here were wildly different. There, to my American eyes the biggest difference was in the separate spheres men and women occupied in public space, the care around every male-female interaction, the headscarves hijabs and full covering niqabs. Here, men and women mingled much more freely. They also showed much more upper body skin, though long skirts and pants were the norm away from the beach.

Especially in the north half of the country here, almost everyone is Muslim, though there are some Christians here and there. On Fridays lots of people -even the children- dress up in their “Sunday best” to go to the mosque for the afternoon sermon, prayer mats slung over shoulders. It’s the men who go, as a rule, though there’s a room in each of the larger mosques for women to pray as well. The call to prayer echoes out five times a day, with imans of varying singing abilities booming over the speakers.

The Sufi sect of Islam is popular here, and singing circles pop up almost every night. The keening melodies repeat, often one line from the Quran. It’ s a sound that I think will always root me in that time and place, and reminds me of the Hebrew niguns I love chanting with my own spiritual group.

Islam also exists alongside -or maybe superimposed on- local beliefs that have existed since the religion reached West Africa 1,000 years ago. Even in the time of the Malian king Mansa Masa’s pilgrimage to Mecca in the 1300’s, elites balanced a profitable foreign religion with existing systems. Tradition medicine, paying for blessings -or curses- from the seurigne elders is still very much a part of life here, though it seems to happen less openly than Islamic practices. There’s also the Baye Fall, a subject of one of the Sufi brotherhoods and followers of Ibrahima Fall (himself a follower of Chiekh Amadou Bamba). They wear white and black checkered robes and often rainbow patchworks, a louder, higher pitched chanting and gourds to collect donations. The small communities from other parts of Senegal exist sometimes uneasily here in the Lebou village, unlinked by the usual family ties.

Systems of Islamic and Quranic schools also exist alongside the public system of French or French & Arabic schools. Students clutching wooden tablets with carved verses are common all over the city, though teacher salaries are controversially funded by young pupils asking for change on the street. There are movements to stop students from panhandling every so often, but the national population is so young it seems like the government feels any system that can look after a portion of the youth can fund itself however it needs to.

Many people here have described Islam to me -especially in conversations about my Jewish heritage- as a religion of peace. Fundamentally, Judaism and Islam seem more like legal frameworks that a culture has sprung up around, though I identify more with the cultural pieces than doctrine. That said, the way Islam is practiced by more of the Senegalese I know offers deep kinship and ritual throughout the day.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Life in Ngor Village

20 years ago the center of Dakar was way down south, ten kilometers at the other end of the peninsula, and the three ethnically Lebou villages of Oakam, Yoff and Ngor existed separately. The Senegalese writer Mariama Ba has some lovely descriptions in her book So Long A Letter. Fast forward to today, and there are at least 10 construction cranes visible at any given moment from anywhere in the city, probably many more if your eyes are sharp. New neighborhoods have sprung up even in the past ten years where there was just scrub-brush, knitting together the former downtown and the outskirt villages. It reminds me of the construction I saw living in China back in 2013, constructing giant ring roads around a future metropolis.

The neighborhood I lived in during my time in Senegal has changed a lot, friends there told me. Lebou elders sold grazing land next door and the swanky neighborhood of Almadies sprang up around the American embassy and other NGOs. Ngor Island a few hundred yards offshore cut down their mango trees and began building houses, many of which were sold to Europeans. Growing families took advantage of lax land laws (and often ancestral land) to build concrete and rebar foundations they could add onto over time. Today, the parking lot by the beach, dirt soccer field, cemetery by the mosque, and the beach are some of the only large public spaces. Smaller squares the size of housing plots still gather vendors and families during the morning and evening hours, sometimes sandwiched in between small alleys. The fishing stocks have depleted, too. My friends’ parents have described all the fish they caught in their younger days they don’t see anymore, and the popular fish now -like the meaty lotte- that were considered waste fish back then.

For all that change, though, Ngor still feels very much like a village. The vast majority are still ethnically Lebou, and related; the same half dozen last names are shared around. No one, it seems, has more than one degree of separation from anyone else. Our downstairs neighbor showed Carolyn a construction site shortcut through the neighborhood she uses when the greetings for ten neighbors to get in the front door seems overwhelming.

The economy still centers around fishing, and the two dozen or so gorgeously painted pirogue boats are still pushed out at dawn by a dozen straining men. Refrigerated trucks roll up on the sandy shore all the time to haul the catch to markets across the city. Kids walk away from the shore swinging giant fish by their tail for the midday wheel, or if they’re too big, with a wheelbarrow. The Lebou are known for being expert fisherman and great swimmers. Some of the men forgo the fishing boats and bring their own setup -bodyboard, flippers, weighted belt and net- to go spearfishing. When the beach fills up after Ramadan with Dakarois from across the city, it’s the Lebou lifeguards who will swim out to fish the non-swimmers from deeper water.

Sheep are everywhere, though they look more like large American goats. They’re stored on rooftops, and little pens, lovingly washed in the ocean on the weekend. Some keep them as large pets year round, some raise them for the slaughter during the post-Ramadan festival of Tabaski. All year we fed our food scraps to the rambunctious herd on the roof of our building. Shifting herds of sheep, sometimes staked and sometimes roaming free was just one more way the physical makeup of the village changed on a daily basis.

Ngor has a justified reputation as a rough and tumble fishing village, where people take care of their own and the police mostly stay out. An example; there were big demonstrations near our home, in early February after the African cup. The president -in a spectacular display of tone-deafness- had promised contested land now occupied by the old airport to the millionaire players on the Senegalese national team. The Lebou claim their grandparents had only loaned the government the land 50 years ago when it was empty fields, and the government claims it was sold. Either way, there were a few days of riot police everywhere, tear gas.

The neighborhood generally felt really safe to walk around in, even at night. The western cultural creep of alcohol and drugs has infiltrated some of the young men of the village like everywhere else, and the parking lot was best avoided late, but other than that all generations walked around at all hours. Carolyn and I were the victims of petty theft twice while we were there -never with the threat of violence- and both times we talked to a village elder, and our things were returned anonymously by the next day. A third time we found a young boy in our house poking around, slipping something into his pocket, and I chased him through the neighborhood alleys until some of the young men who worked at the ferry stopped him. (He’d taken a key) They berated him by name, then the father was promptly called, and the unfortunate boy was hauled off with the family. All the kids around heard an impromptu sermon on Islam and proper behavior.

Wedding tents popped up all the time, everywhere without warning. Sometimes they were next to our house, sometimes down the alley, sometimes near the village round point. Gorgeous matching dresses and headscarves for women, long robes for the men, drumming that started late at night. There were several other ceremonies that happened regularly, too. When well dressed neighbors lounged in chairs outside houses, it was a good bet a baby naming ceremony was happening inside, and when the cobblestones were covered in a truckload of sand, it meant a traditional nup healing ceremony had just happened or was about to. A cow being hauled into the beach spray was the other sign sickness was being washed and chanted away. Drums beat a rapid trance pattern late at night and dancers moved around the sick as the spirit moved them. The sand was to catch them if and when they fell back down, exhausted. The way neighbors gathered in the hundreds in these small spaces late at night and dispersed just as quickly never stopped surprising me. In addition to the constant piles of sand and gravel and excavated water trenches that changed walking paths weekly, the human blocks of celebration kept walks around unpredictable.

Carolyn and I were never invited to a marriage or naming ceremony while we lived there, probably a function of our limited Wolof language capabilities. Still, we knew by name and more by face dozens and dozens of neighbors by the end of our time there, and our own walks around took longer and longer as we asked about family and health.

Our home was a rooftop terrace apartment that looked out over the ocean, Ngor Island, and the hive of activity that was the parking lot. Sitting on the terrace during the morning and sunset, alone or with friends, is one of my strongest images of the time there. The entrance was tucked behind a labyrinth of small alleys that never stopped confusing our friends. The owner and his extended family lived downstairs in the many other apartments. A family of sheep lived on the roof. We found it with village connections; the wonderful manager of the surf camp lived downstairs, and it seemed like most of the spaces in the village proper were like that. You could find a place through a rental agency on the outskirts, but even Google Maps gave up trying to trace the alleyways of the inner village where we stayed.

There were more non-Lebou people -foreigners like us as well as other Senegalese- slowly moving into the neighborhood, but gentrification was arrested by social ties. The Lebou, by and large, didn’t want to move out of their three traditional villages, and they owned large enough plots that they could rent out a room or two while still housing large families. The money they could make from selling wasn’t enough to make them break multi-generational ties to move. That line of defense made me proud to live in the village, and more than a little sad for the vanishing ties like that back in America.

In so many other ways, Ngor reminded me of the stories I heard by grandmother and other elders tell me about growing up. Wistful remembering of running around in gangs with there other urchins until they came in filthy after dark, a mix of agrarian and city life where you dodged horse carts and sheep herds next to the cobbler. One of my older neighbors had a grandson who was living in America. He was getting in trouble in school there, and she insisted he come back to spend his early years running around in the sand here with the other ankle-biters. I met him. He looked deliriously happy. I wondered if he’d had culturally competent teachers who recognized the buzzing energy of a young black boy as the gift it was. I have a feeling my American neighborhoods back home will seem so very lonely and empty by comparison. Even so, I couldn’t be more grateful to spend my year in Senegal living in Ngor Village.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Casamance Travels

I took a one week vacation with Carolyn -and for the first few days my friend Anne- down to the verdant southern province of Senegal called Casamance. The trip was loosely planned around a concert with with some musician friends from Dakar, exploring a bit on our own, and staying at the family farm of a neighbor in Ngor.

April 18th Monday Overnight slow boat travel is the way to go! It’s like buying a ferry ticket with a free hotel, or a hotel room that magically transports you where you want to go. Private cabin was lovely, and no one else stayed in the four person cabin but Carolyn and I! Woke up to sparkling water and mangroves and -no joke- dolphins swimming alongside the boat.

Writing after the concert with Youssou, so much fun dancing to his music, hanging out with the band -Paulette and the others. It felt a little icky to be in a nice hotel rather than a local hangout, and overall I’m not a huge fan of Cap Skirring. I must be missing the community heart, because right now it just seems like a lot of expats slouching around huge dispersed properties and a service economy.

Casamance has such a different feel than Dakar, which makes sense. New geography, climate, flora, ethnicity and languages spoken here. These endless river estuaries of mangroves and oysters, the green I didn’t know I was missing until I saw it here. My fledgling Wolof evaporates here in the face of regional Djiola dialects as well as the Pular and Mandingue communities. The Dept of State warns against travel to Casamance due to rebel activity in the northern parts. We weren’t planning on going there anyway, but I wonder if that’s true?

April 19th Tuesday

In a hotel in Ousseye, so many interesting facts on the walking tour from Monsieur Bonfils I don’t want to forget. The animist tradition of burying bodies, then moving the bones to the side, intermingling ancestors. Offering a drop of palm wine to the ancestors first. The massive drum to announce deaths and battles between villages. The towering, sinewy fromager trees. Mangos, papayas. The cashew trees, and the fruit, and 5 step process to dry, roast, crack, grill, finish the nuts.

April 20th Wednesday

Final day in Ousseye I think, close to perfect adventure with Carolyn, triangle shape mountain bike tour between 3 towns, first leg a sandy patch, still lovely to be on our own. Kid and his friend rolled up alongside up sharing a bike as we came into town, or rather we passed each other and they wheeled around to follow us. Younger, but so damn self possessed, said he’d take us to a nice place on the river, and he sure did, community center/restaurant. Went swimming with the boys Abdo and Ibrahim, talked about lots of things, his sense of right and wrong, preference for Casamance (others have said this). And when I asked the guy working there -Gir- if it was possible to get oysters, he ended up taking us on a grand adventure with his buddy on a boat deep into the mangroves. We hung out at a backwoods palm liquor camp, with some rough and tumble fellas sleeping on old mattresses, braided hoops for climbing the trees and machetes and knives buried in an old trunk. Watched them fill up nearly 100 liters of palm wine from old jugs to sell, showed pictures of rock climbing and described the process of making maple syrup. Then on the way back hacked off the roots of a few mangroves and pulled up 20 lb poles of oysters. They made a quick fire of palm fronds and ten minutes later we shucked oysters and ate them with a yassa onion sauce. Teranga on steroids. I can’t imagine taking strangers for three hours on a trip to scratch an itch of theirs. I mean, we all ate together, but still. Then biked the last two legs, groin killing but at least it was paved. Passed ever more majestic forager trees. Cold beer on the return at sunset, trying to coax my Spanish back to life with a tour group, and voila.

Friday, April 22nd

Yesterday was a bit of a travel day back to Ziguenchor. Nice and well organized and standardized transport hub outside of Ousseye. Checked into a musty and too small hotel -Sangamar 2- a little ways out of town. Went for a nice afternoon walk while Carolyn worked, one end of the town to the other, passing lots of industrial equipment and oyster mountains, ending up at a trash strewn but otherwise nice beachfront bar with a hammock. Anyway, made it to Rosie’s brother’s house after 4 hours, in Thionk Essen. He looks like a rasta Don Cheadle, incredibly kind, reflective and open prodigal son farmer man. Came towards the end of the day so we just went to his family’s land where a couple folks were working on the cashew apple harvest. So sweet, so tasty, liquid sunshine. Promised we’d help the next day, and will. Then, back to the family compound, playing with babies, being introduced to the 15 or so people of all ages around the house. Went for a nighttime walk, hearing all the sounds coming from the houses, ate a couscous group dinner, drank a little tea and more cashew fruit juice (which is good because our water is almost gone) and then reposed, which is what I’m doing now! Unsure of the hosting etiquette, five days seems like too much to expect, although if it weren’t an issue and it’s just our American non-teranga radars it would be lovely to fall into the rhythm of family life a bit more.

Monday, April 25th.

Already walked around the village, greeting everyone and their mother, literally. One has a daughter living in Colorado. So glad I got talked into visiting the school built by Spanish architects, it’s a thing of beauty and makes me miss the classroom. That English teacher -Babakar- had GREAT explanations, much better than mine in Spanish. “Building schools in Africa,” always seemed like a cringy, self aggrandizing act from a Westerner,, but now that I’ve been here and seen the community pride and participation, I get it more. Outdated curriculum and dubious employment chances in a gorgeous school setting still isn’t transformative, though. The family plots; 40 meters by 40 meters, enough to have a working farm if you put just two parcels together, and a helluva open space and garden with just one. The space is massive, massive, and the open design makes me dream -just as it did in Spain and Morocco- of living with intergenerational family in a giant compound. Or friends, especially if everyone has their own kitchen and bathroom. Evening thoughts, after a hot, bee filled afternoon on the farm, filled with smoke from a nearby brush fire and the guys on the farm muttered nervously. The helplessness of communities like Thionk Essen that don’t have a fire brigade that goes out that far or a government official to monitor wildfires. Climate change is all too real here.

Tues, April 26th

Just visited the future community site of Dallo, who grew up here, married an American and moved to Colorado Springs, where she now teaches dance. It’s a beautiful structure, circular, big center courtyard, half finished, with the cinderblock being slowly covered by mortar. How much mortar it must take! Is there a way to make concrete locally? What’s the active ingredient that makes it solidify so tightly when mixed with water? If it were cheaper, more could be covered. I think it’s a silly old tendency of mine to want things to be painted and bright when the gray concrete blends in more closely with the earth. Again, overwhelming hospitality, so much that I think I don’t have it in me to reciprocate in the same way, to plan everything around my guests. Kanie is such an interesting conversationalist, someone the young kids in town look up to, the reason they follow him out to the farm in the morning. He has an old soul in some ways, prefers to walk the half hour route along the road in the early morning rather than bike. He worries about the influence of the new Chinese made motor bikes in town, which can be bought for $500 and have led more than a few young men to drop out of school and lounge around on their crotch rockets at the transport hub. He worries that fewer and fewer people are willing to make the five kilometer trek out to the traditional rice fields to replant. The old town was razed years ago, rebuilt with modern blocks and these big family blocks. While in some ways it’s a success story of urban planning, it also means the oyster shucking grounds and rice fields are much farther away now. If there wasn’t cultural pressure to provide the traditional rice at weddings, if it even would have survived in town this long. Some of my fondest memories are talking with Kanie across the old bridge of lashed wooden poles, atop the literal oyster mountain, an artificial island built of millions of pounds of shucked oyster shells from who knows how far back. A giant baobab grew out at an angle, and the trunk was rubbed shiny from generations of feet clambering up.

Thursday, April 28th

On the Aline Sitoe, the giant ferry from Ziguenchor to Dakar, travelling “home” to Dakar and Ngor, which depending on the day has quotation marks or not. The boat is named after a young woman who resisted the French command to cultivate peanuts at the expense of the traditional rice. She was hugely respected even in her early 20’s, and died in exile. It seems like France never did seem to colonize this region as well as northern Senegal, too many lush inland places to hide. I was surprised in asking Kanie’s family about the independence movement. His brother had been stopped at gunpoint and robbed by the rebels too. The family seemed disgusted by what started out as a legitimate movement to recognize the province’s distinct identity -like Catalonia in Spain- and underinvestment versus the northern region. Then, according to them, it devolved into more petty banditry.

I could see living in this place after the time on Kanie’s farm and with family, though maybe that’s more to do with simple country living. Overwhelmed by watching him maintain social ties with everyone in town, when I maintain that in my own school village. Grateful for that. Takeaways, connection with the earth, the toil to grow the earth fruit I eat absentmindedly as snacks. The labor involved in producing a bag of cashews. How good it feels to hang out with family -blood, adopted or chosen- of multiple generations. It feels centering to have babies and toddlers and high schoolers and grandparents and maybe great grandparents. The contrast places me firmly in my life path, or rather, more appreciation for the current stage. Carolyn and I have never done this before, but we decided to offer Kanie a zero interest loan to buy a big solar panel. He never asked us for funds, but in talking about his dreams for the farm he has such a clear vision of how to expand production -and the jobs he can offer- with a solar panel to power the water pump for the well. Having hauled up endless buckets by hand while we were there, I can see what a game-changer it will be. Carolyn will draw up a promissory note, and we’ll send funds when we get back. It’s funny, seeing people keep to themselves on this boat. When I had to greet everyone in town all the time it felt stressful, but I already miss it. To be greeted is to be acknowledged, and what feels better than that?

0 notes

Video

tumblr

Feb 6, 2022: The African Cup

The Senegalese national team is the best it’s been in years, and it seems like the whole country is cheering them on during the African Cup. Some memories: Watching the quarterfinals in Chez Roger against Equatorial Guinea, the small, smoky dibiterie, as sheep carcasses were stripped and chopped into kilo and two kilo piles next to us, customers walking in front of the screen to pick up there orders, the thwack of the butcher knife in rhythmic time to the announcer chants.

Watching the semi-finals against Burkina Faso in Le Parisienne with neighbors Amadou, Helene, Ibou. Amadou is so intense, so into it, and the release when they won was a group catharsis like I’ve never seen. Cars honking, shouting. Then, the finals, going back with Jelani and Carolyn, the Senegalese flags plastered everywhere. The Egyptian goalkeeper saving the early penalty kick at minute 7. The long, scoreless match, so many chances for the Senegalese team, both goalkeepers superb. The roar in the street when the second to last penalty kick went through! Everyone making as much noise as they could, hugging each other in the small cafe, running out the door and back in. People banging on pots and pans, blowing whistles, car horns, anything, jumping in cars, riding on top, spilling out, fully a dozen people packed into each car, a cavalcade of stunt riders that were just excited Senegalese fans decked out in green, yellow, red.

We walked the long way around and back to the village. Sometimes a red flare gun would illuminate the night, or fireworks, but mostly cans of hairspray lit and used as flamethrowers. People yelled, everyone seemed to be simultaneously recording on their phones and participating, except for the foreigners who watched, dazed, and those painted and flag draped fans who blazed in the moment and couldn’t be bothered. I wanted to dance, crazy, but every time I started it turned into the toubab show, cameras being trained on me. People were laughing and encouraging, but, still, it was their moment, and it should be my neighbors in the spotlight. I restricted myself to a practice I’d seen Senegalese men doing, running into the middle of the circle when it formed, dancing wildly for a few seconds, and running as quickly out. Running into Madame Rosi, who owns a restaurant a few blocks away and her son was lovely. We said goodbye to Jelani and headed home, thinking of going out again, but lost steam.

And then, astonishingly, the next day, the team arrived at the airport in the afternoon and the party started up all over again. President declared a holiday, no school. Even more Senegalese flags and outfits this time, the fashion forward capital making every kind of pants, skirt, cap, cape, hat out of the flag. Painting their faces, or bodies, weaving colored strands into their hair. I saw a man in a full body flag suit on skates pulled behind a motorcycle. The whole city seemed outside, walking, waiting, cheering, for the motorcade to pass by, or maybe not, maybe just being together was enough.

0 notes

Photo

Travels To The North, Lampoule and Saint Louis