Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Artist to look at

Willie Doherty - car videos with voice over

0 notes

Text

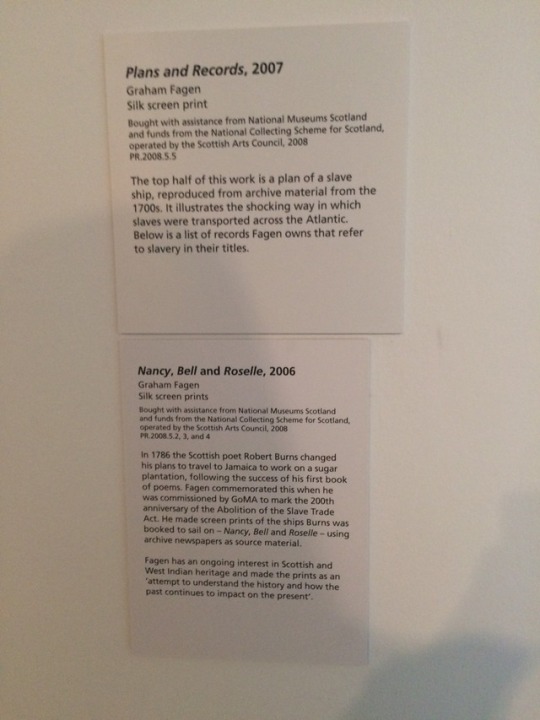

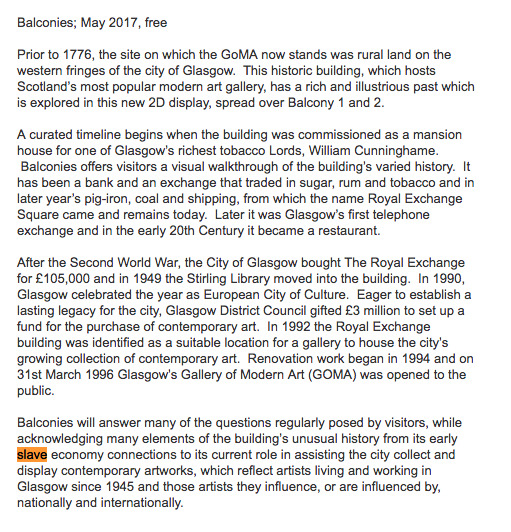

Michael Morris - Slavery Courses that may find source useful: The Atlantic Slave Trade, Changing Britain

Dr Michael Morris of Liverpool John Moore’s University examines Britain’s role in the Atlantic Slave Trade through a focus on taste – the flavour for foreign goods that global trade inaugurated, the culture of taste that sustained the desire for imports, regardless of how they were manufactured, and finally how slavery and the trade eventually became distasteful to British society.

Section 1 download

Section 2 download

Section 3 download

Full audio download

Section 1

The American travel writer Bill Bryson once observed that there is nothing that galvanises a British person quite like the prospect of a cup of tea. ‘Cup of tea?’, they’ll say… ‘ooh yes’, they’ll say, ‘lovely’. We have come to think of tea as quintessentially British. High tea, afternoon tea, tea parties, tea houses, tea with milk and sugar and scones: instantly recognisable as staples of everyday British life.

My central object today is this teapot from the 1750s. You’ll notice the image of a well-dressed, well-heeled couple enjoying a very pleasant, perhaps romantic moment, at their tea table. The couple hold their cups and saucers, the lady daintily stirs her tea with a tea spoon. The tea table itself is covered with all the paraphernalia of the tea service: sugar bowl, milk jug, and salver. What is most striking about the image though, is at the left hand side, we have a young black man pouring them their tea from a tea kettle.

So what this teapot suggests is not so much a singular national story, instead it opens up an international global story. The teapot is an early product of globalisation: vast webs of trade and international markets. What’s more, it suggests the rise of a wealthier group that was interested in conspicuous consumption in Georgian Glasgow. But, most importantly, we remember the people who laboured-- servants, serfs and slaves-- upon whom all of this wealth relied. Georgian Glasgow’s web reached to the East where tea leaves were cropped by forced labour in places like China. From the West, came the sugar that sweetened it all from the sugar islands of the Caribbean. From the South, millions of people in Africa were enslaved and transported to the Caribbean to grow the profitable crop. Alongside ‘Tobacco Lords’, Glasgow had ‘Sugar Barons’-- Merchants who made huge profits from sugar, so that it became known as ‘White Gold’. This elite group, their wealth and influence relied, in large part, upon enslaved labour in the West Indies. A global web of wealth for the few that relied upon a global web of labour of the many.

3min

This teapot is from the famous pottery firm of Josiah Wedgwood, it dates from the middle of the eighteenth century, around 1750. Now Wedgwood is also well- known for producing a token that would become the most popular Abolitionist symbol. It showed a figure of a kneeling slave holding up his chained hands and pleading—‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’ So the Wedgwood connection leads us to think about the sea-change in attitudes around slavery that took place between the middle and the end of the eighteenth century.

From the middle decades of the century, Britain became the leading slave-trading nation from Africa to the Americas. Its wealthiest and most prestigious families often had significant interests in slavery. Glasgow, famously, was less involved in the slave trade, but played a key role in the trade of slave-produce. ‘Let Glasgow Flourish’ was the slogan, and so it did on a new consumer boom, with increasing demands for sugar to stir and tobacco to puff. From 1787 onwards, however, the Abolitionist society co-ordinated a mass campaign against the slave trade that would lead to its abolition in 1807, and finally the ending of slavery itself in most of the British colonies in 1834.

Section 2

So my central theme here is TASTE and three different connotations of the word. I want to think about Taste in the sense of flavour, tastefulness and distaste. Firstly, then, taste in the sense of FLAVOUR. As the 18c progressed, the web of global trade transformed the relatively meagre national diet with a whole variety of new foods that came from the far reaches of the empire. Weird exotic luxuries like potatoes and chocolate became staples. Hot drinks like tea and coffee, as well as the sugar to sweeten them, must have seemed ideal in our cold climate.

1720s 9 million tons of tea imported. By 1750s, the time of our tea pot, this had risen to 37 million tons.

These new products drove a transformation in tastes and behaviours. As Robert Winder says: ‘We became a nation of cups and saucers, dainty plates and silver spoons.’

The consumer society was born and social life changed with it. Rather than only taverns, now Coffee Houses and Tea Houses sprang up where people could meet in public. Rather than stupefying ale, caffeine got people chatting—from everyday gossip, to philosophy, from discussing the daily journals, to merchants concluding deals. A bit of a difference sometimes emerged between tea and coffee. Coffee houses tended to be more of a public, masculine world with high powered merchants; tea could be consumed at home around the tea-table and so was sometimes associated with a more domestic, female world. Some might say that difference between coffee as more of a public drink and tea at home continues today.

I’m going to come on now to my second point about Tastefulness. All these new tastes and flavours developed a consumer society. New wealth and new products developed a ‘CULTURE OF TASTE’. This meant that newly wealthy people liked the finer things in life, they liked to be seen to be wealthy and stylish so they decorated their homes to show that style. Fancy tea services with beautiful silver tea spoons and colourful sugar bowls showed that they were part of that high-society club.

Now to focus back in on our tea pot. This is an earthenware tea pot which means that it would have been more affordable for those on a more modest income, rather than a high society one made out of porcelain or china. The image is a transfer, it’s not hand painted, so it could be more cheaply produced. And yet, in terms of the image, we have an elite couple with their own black domestic servant. We can imagine that the image functions a bit like a television advert nowadays which tells you that if you buy this product you will enjoy a more glamorous life. By drinking tea from this tea pot, you will be lifted into high society, this elite culture of taste.

The image reminds us that, many black people were present in Britain as Domestic Servants in the 18c. Estimates range from 10-40,000, and so far we have counted around 100 people in Scotland. Famous Enlightenment figures, such as Samuel Johnson and Lord Monboddo had black domestic servants, named Francis Barber and Mr. Gory respectively.

As a result, it is quite common to find representations of black servants in the art and material culture of the 18c. In addition to our teapot, you can hear about the Glassford Family Portrait in another talk in this series.

It is intriguing to ask a few questions:

1. How were these black faces presented to the eighteenth century public?

2. And how has the Meaning of the Image has changed over time.

In the 1750s, to choose to depict a black servant on our teapot would seem to increase the prestige of the couple, it would increase the sense of their wealth and exotic stylishness.

However, the thing to remember here is that although the couple and the servant are on the same image, close beside each other. In fact, these images worked to create a distance, a mental gap, between slavery and our cup of tea with two sugars. There is a mental gap between the hard conditions, the sweat and violence of its production in the East and West, and our stylish couple drinking the tea in a pastoral British garden.

We can say the image is ‘sanitised’- which is to say slavery has been cleaned up and made to seem more acceptable, more tasteful. Although the images are based on Africans, all of whom were transported from the chaotic slave ports of West and Central Africa, the image forgets all of that painful side, and instead depicts the black figure in a calm and peaceful world of taste, wealth and style.

It is noticeable that the black man is younger, smaller, and positioned lower down than the couple. He himself is dressed in fancy servant’s clothes- while the features of his face are practically invisible in comparison to them.

Nowadays, then, the image speaks to us of something different. The image reminds us of the slavery and racism that this couple’s wealth relied on. We notice that they are not looking at him and the man’s off-hand gesture looks like indifference and disrespect.

Section 3

To come on to my third point, later in the century abolitionists succeeded in making slavery DISTASTEFUL. After Parliament rejected the abolition bill in 1791, abolitionists bypassed parliament and developed a new strategy- the boycott of West Indian sugar.

If the politicians could not be persuaded, this would be a consumer awareness campaign that would hit the Sugar Barons in the pocket. Abolitionists understood that decreasing the profits gained from the sugar trade would take away the major justification of slavery. The boycott strategy was used first in 1791-93, and was revived in the 1820s, during the push to abolish slavery in the British colonies.

The Abolitionists were intelligent and targeted their campaign directly at consumers. For example, the poet William Cowper published anti-slavery poems, like ‘Pity the Poor African’ which was advertised as, "A subject for Conversation at the Tea Table". This publication was targeted at the middle-class housewife, who, the abolitionists believed, controlled the purse strings in the house, and could make the decision over whether or not to buy slave-grown products like sugar.

The Abolitionists worked hard to close the mental gap that existed in the Culture of Taste between slavery and the sugar that you stir in your tea. The poet, Robert Southey, described tea as “the blood-sweetened beverage”.

An anti-sugar pamphlet by William Fox was published in 1791; it ran to 25 editions and sold 70,000 copies in four months, one of the most successful pamphlets of the time. In it he argued,

“If we purchase the commodity we participate in the crime.…In every pound of sugar used we may be considered as consuming two ounces of human flesh” (William Fox, 1791, in Address to the People of Great Britain).

Instead of the sanitized vision of sugar and slavery, Fox here gives a vision of cannibalism, eating sugar is eating people. It doesn’t get much more distasteful than that.

A letter to the Glasgow Courier newspaper in January 1792 continues the theme, arguing that eating sugar was equivalent to whipping a slave yourself.

It was an effective campaign, sugar sales dropped by a third in some parts of the country. By 1792, about 400,000 people in Britain were boycotting slave-grown sugar. Some people abstained completely, others used sugar from the East Indies, where it was produced by freer labour.

At this time, Josiah Wedgwood produced the token with the image of a kneeling slave in chains and those famous words 'AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER' around the rim. The image was reproduced on a variety of Wedgwood products, such as brooches, hairpins, bracelets and pin boxes, that signalled a new consumer culture of anti-slavery.

However, many people have since criticised this image as it shows the African still on his knees and begging for help. It seems to remove any power from the African and suggests he needs to be rescued. This reminds us that even abolitionist images could contribute to the problem that even after the abolition of slavery, the issue of racism continues up to this day.

In conclusion, what we can say though, is that this form of campaigning empowered anti-slavery women to play an active part as consumers, though they were excluded from formal political power. The abolitionists succeeded in challenging the sanitised imagery of slavery. In the late 18c, it became as fashionable to be against slavery, as it once was to have a black domestic servant pouring the tea.

Manufacturers began to make sugar bowls and tea sets with anti-slavery slogans on the front. They declared that they only bought ‘East India Sugar Not Made By Slaves’. The Tea-Table had become a slavery-free zone.

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

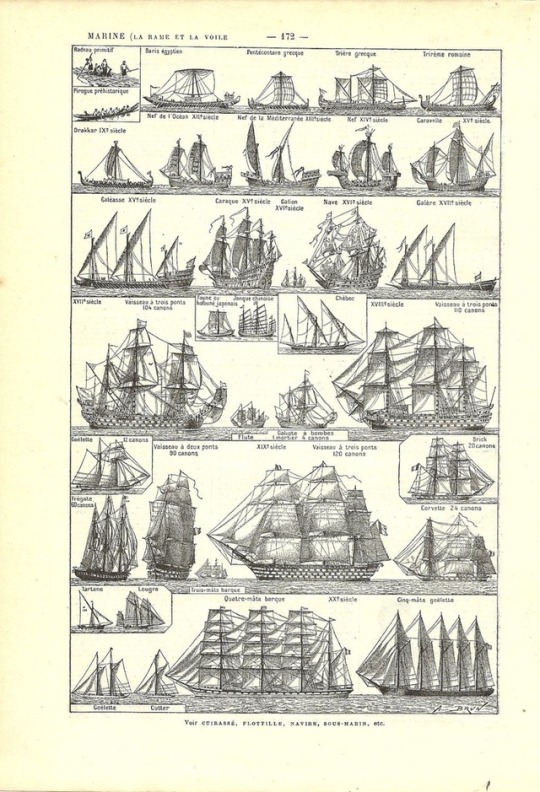

Could do a lithograph of 18th century boats and just call it caledonian sleeper?

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes