Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

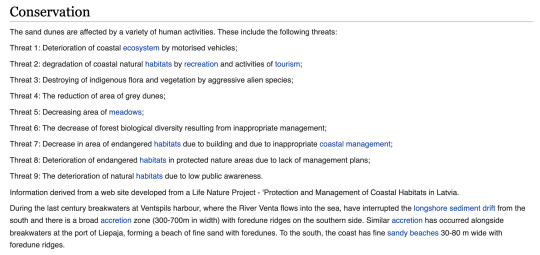

conservation of sand dunes

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20191108-why-the-world-is-running-out-of-sand -->

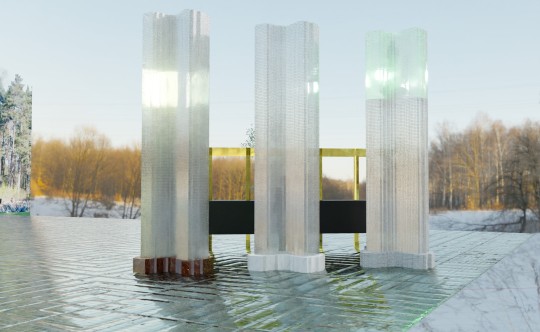

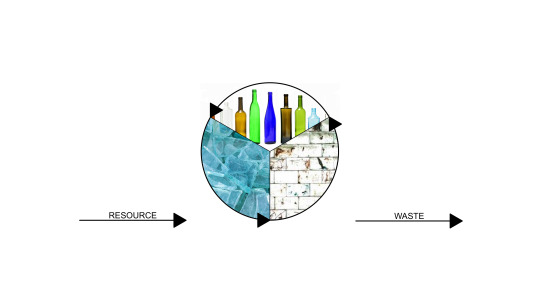

Sand is the second most-consumed natural resource on the planet after water. The construction industry is the largest sand consumer. Generally speaking, two-thirds of a building is concrete and glass, two-thirds of which is sand. The sand from deserts is mostly useless to us due to its smoothness. Therefore we exhaust the sand of river beds and seashores. Low public awareness and mismanagement also endanger the typical sand dunes along the Latvian coastline. Therefore we propose to decouple the used construction materials from natural sources and give already processed resources a second life. In Latvia recycled glass is mainly used in street construction. The precious and beautiful material is thus invisible and removed from possible future recycling. Our structure is free of mortar and compresses the glass bricks through tension cables inside the columns therefore the glass can have a new life cycle at any point.

0 notes

Text

Cycles

Life comes from life; human beings emerge embodied from another body to perpetuate the cycle of birth, death, and decay. Cycle and Recycle — all things recycle. Everything is a cyclical repetition with minor variations, as we see in nature (the repetition of seasons, life and death, the cycle of the weeks, months, etc.). Night and day or winter and summer are the complementary poles of larger cycles, rather than as mutually exclusive opposites. And if the coming to be of things is cyclical, it is necessary that each of them is coming to be and has come to be: and if their coming to be is necessary, it is cyclical. Why then do some things manifestly come to be in this cyclical fashion, as, e. g., showers and air, so that it must rain if there is to be a cloud and, conversely, there must be a cloud if it is to rain, while men and animals do not return upon themselves so that the same individual comes to be a second time?

The Columbarium is a place held within a temporal paradox of the symbolic order, a space that is torn in two different directions at once. Its stories take place in a strange time loop: time is frozen within its shelves, but the people and nature are celebrating cycles all around. They perform rituals and grieve and grow. When the community gathers to carry out this simple action of eating and drinking, the event is attended by a sense of magnificence which intensified the feeling of joy. By celebrating, the community is welcoming Nature and rejoicing in its gifts; more than this, it is associating Nature with the human community, binding the two together. And there are external factors that surely have a bearing: the unpredictable fluctuations of the weather, the cycle of the seasons, the irregularities of terrain.

Goethe characterizes architecture as “frozen music”. But “frozen music” is cold, raw, (…) and has neither warmth enough to relieve, nor gray enough to harmonize with, any natural tones; it does not please the eye by warmth, in shade; it hurts it. The question I would like to ask is the following: can architecture break out from its frozen state ? Can it be put into a cycle ? Surely, there must be some convenient way of following the cycle of the seasons? By readmitting the transitory, fluid, and contingent aspects of modernity back into architecture, the fullness of time is released from his frozen vignettes and his empty space is repopulated.

It is always wise, in planning a Columbarium, to plant about a pergola from two to four kinds of flower bearing or fruit bearing vines, so that each season will have its fragrance and color. It is also interesting to plant rows of shrubs at the foot of the supports and between the supports, that the whole structure may be more intimately connected with the ground. The sequence of the seasons is elucidated in the planting through the reality of fruition in the color seen as dominant in each season – green in spring, yellow red in summer, white in autumn and black (or deep purple) in winter. Time differs, however, from human life. Spring is not my spring, Nor is summer mine, Nor is autumn, Nor is winter, for that matter.

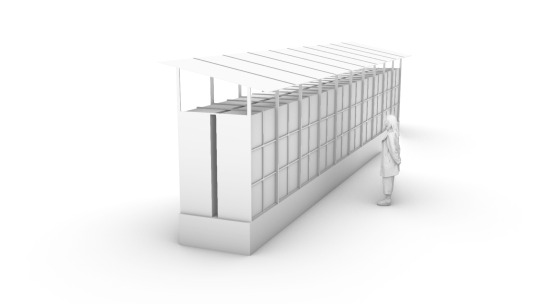

For that very reason the sight of the Columbarium gives a sensation of open air and warmth —all the more so because, (…) by virtue of the liturgy and ritual in which it is so profoundly versed, its glass facade connected with the season and the hour by a bond both necessary and unique, the flowers on the flexible (…) brim of its roof, the ribbons on the glass, seemed (…) to spring from the month of May even more naturally than the flowers of garden or woodland; and to learn what latest change there was in weather or season, (…) its entrance is open and outstretched like another, a nearer sky, round, clement, mobile and blue. The most popular feature is undeniably the outdoor, 10,000 square foot linear ice skating rink. In the summer months, the rink is converted into a 42 jet interactive fountain, also very popular among residents and visitors.

But let’s not forget where we are. Everything here still bleeds and suffers. A great mystery is taking place. On all sides death meets the eyes, and we are tempted to weep. Nevertheless, may not this immortal death, the image of which art inscribes in an efflorescent vegetation, this flower of the soul, this divine fruit of the world, which nature decorates with her leaves and her roses, may it not be life and love under a mortuary form? These sombre arches may conceal the marriage rites beneath their gloom. Are not Romeo and Juliet united in a tomb? It is not at all about wandering souls, ghosts and ghouls, but about appeasing nature, preparing for the change of seasons from the abundance of autumn to the privations of winter.

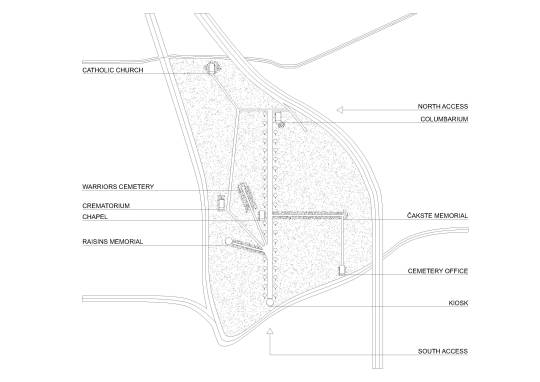

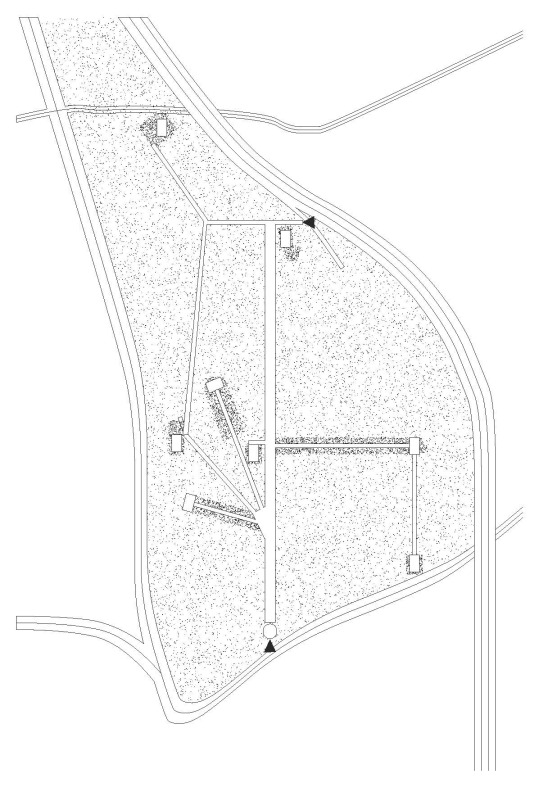

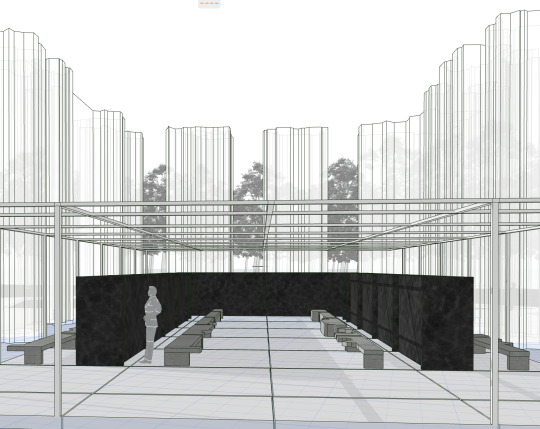

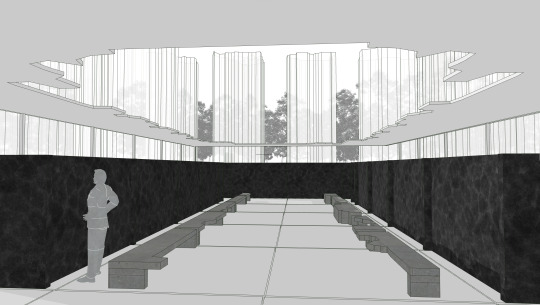

Let us take a closer look at the architectonics of the Columbarium. The northern façades, with few or no windows at all, are constructed of thick masonry walls to keep out the cold winds in winter. (…) The courtyard serves as a private outdoor room and provides light and solar heat to the adjacent indoor spaces. The entrance to the Columbarium is from the street and leads directly to the courtyard. Surrounding the courtyard are all the other rooms, which opened into it. There are two layers of transparency—one from the exterior to the occupied spaces and the other to the atrium interior. (…) The building utilized a borehole system from below grade where naturally chilled water is circulated through the structural beams in summer. In winter the water is heated before being circulated throughout the atrium.

The water is routed in clear conveyances, treating visitors to both the motion and sounds of flowing water, without compromising water handling standards. Rainfall is processed through small wetlands on the building shell, to an interior pool, then to a cistern beneath the building and an exterior pond. The water then supplies on site greenhouses. Interior waterfalls create sound and cool the air in summer. The portico and roof eaves served to shade the sun in summer. Grapevines on the roof thicken in the summer, providing shade, and thin in the winter, letting the sun's rays through.

One will notice to their astonishment that the light plays in these forms and that an air space surrounds this form. One will see by entering the glass skin, how these forms grow into the air space and on the other hand, surround and enclose it. With the use of glass, it does not depend upon the effect of light and shadow, but on the rich interplay of light reflections. It also shelters one from the east wind, and ripens one’s peaches and nectarines, and glows in autumn like a sunny bank.

The inner chamber hosts all the artifacts; Wax flowers under glass cases, or a left over ormolu clock: dried flowers in the fireplace in summer: immortelles in a wreath around the portrait of a deceased member of the family—dust and desiccation, fancywork and ornament: in short, the art of the what not. The leaves dropping from the trees in the autumn, the interior of an airplane engine, the entrails of a dissected rabbit, the city desk of a newspaper, all appear to be chaos if they are seen without comprehension. Once they are understood as systems of order, they actually look different.

0 notes