All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is. Take it moment by moment, and you will find that we are all, as I've said before, bugs in amber. -Kurt Vonnegut Art, writing, photography and...

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I&R - Full Interview

For Josh Cournoyer, a move to Nashville, after being a fixture in the Providence music scene for years, never really erased the scene from his life. This year, Josh has found himself creating his first solo album under the moniker I&R that works to reconcile his feet planted in both worlds.

I&R presents Bankrupt City as a collection of folk musings, fast and slow, hard and soft, all with an edge of pause and existential reflection. With a solid foundation in Josh’s rich, literary lyrics and deep, baritone voice reminiscent of The National’s Matt Berninger or Last Good Tooth’s Penn Sultan, Bankrupt City comes together as a collective approach to creating and recording with various players, each having their own expression and a conversation with each other.

The following is the unedited conversation with Josh Cournoyer about I&R, Bankrupt City and his Friends From Back East Tour:

Photo Credit: Micah Mathewson (Mathewson Imaging Co.)

Q: What went into your choice to have your album release in Providence as opposed to Nashville?

Josh Cournoyer: Providence has been so generous with support over the years and I couldn't shake the idea that this is where I was meant to be on the night the record comes out. I started playing in bands twenty years ago this summer and there's only one place in the world where I can play a show to a crowd that's been there for most if not all of that journey.

Q: Will you be touring with the same musicians featured on the album?

JC: MorganEve will be joining I&R for the night of the album release which is significant because of how much she brought to the sessions for Bankrupt City. The touring band will be include bassist Nick Sollecito (another PVD transplant to Nashville) who has been playing with me since shortly after we finished making this record and will be featured heavily on the next one. Mike Murdock from Smith and Weeden didn't appear on the record but will be with us for the duration of the Friends from Back East tour behind the drums. We'll also have some guests for the shows on the tour, I&R doesn't have a set lineup so we're always finding new ways to include some of our favorite musicians.

Photo Credit: Micah Mathewson (Mathewson Imaging Co.)

Q: Your album is very rich in sound and full in instrumentation. How much of it was envisioned and how much came out in studio sessions?

JC: I have a small home studio where I did a lot of the initial demos for Bankrupt City. Half the songs had a full band arrangement pretty well roughed out before we started recording, but over the year that we made the record we added a lot. I had a lot of trust with the other producers and musicians on the record, which is why we ended up with string arrangements over marching band drums, or a synth lead giving way to pedal steel. Mike and Arun played a big part in the initial sonic blueprint, Joe and MorganEve breathed so much life in during overdubs and mixing.

Q: Would you say this is your first big recorded production since moving to Nashville? Does it feel like an album that could have only come out after moving? Or could this album have been made in Providence? Was it an inevitable collection of songs or a product of place.

JC: To me it's equal, Nashville taught me to fall in love with my craft, but Providence had always instilled that this thing is ultimately about making art. I needed to grow when I moved here, both creatively and as a person. Things that I took for granted gave way to a reality that Nashville would be just fine whether I made records or not. I'm so fortunate to have great mentors, everyone who played on this record has taught me how to be a better musician. How to enjoy what we do and bring gratitude to the process. At least half the people involved in the making of Bankrupt City have Providence roots, having them beside me in making a record in Nashville was one of the greatest thrills of my life.

You can find I&R’s music here.

#I&R#bankruptcity#rhodeisland#nashville#music#writing#indie#folk#interview#providence#monthly#joshcournoyer#musings#philosophy#emo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Freakbag - Full Interview

Providence art/noise/eclectica duo FreakBag has made a name for themselves over the past two years playing live every chance they get in state, out of state, wherever the freaks are. With a brash yet cleansing simplicity to their Fat Piggy EP, FreakBag offers a collection of sayings, turns of phrase, blips, scratches, riffs, and lo-fi drum machines that remains something altogether refreshingly different. Not trying to be anything other than itself, FreakBag works to make themselves an entity built for experience over studio sounds.

I featured Freakbag in the June music column of Providence Monthly.

The following is the unedited interview with Hana Ko and Johnny Sneeze:

Hana Ko and Johnny Sneeze

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SAVANNAH BARKLEY FOR PROVIDENCE MONTHLY

Q: Freakbag has a psychedelic, art-rock, noise appeal that captures the spirit of Lou Reed or Hella. What do you think it is liberating to play genre-defying music that doesn't necessarily conform to anything in particular?

Hana Ko: The fact that we aren't stuck in one particular genre is the fun part! We don't have any rules. If we want to try out a sound, we can. We get to do whatever we want!

Johnny Sneeze: I think what is most liberating is exactly that; not being tied to any one particular sound. Personally I get tired of hearing anything that always stays the same, so I like being in a band like Freakbag where we have the creative room to do whatever we feel like.

Q: Your lyrics walk the same line as magical realism walking a line that is either absurd or highly profound. Where do your lyrics fall into the writing process? Do you write your lyrics to fit the music? Or do you write your lyrics separately and put the two together?

Hana Ko: I write mostly all the lyrics. Usually things I find funny, or word combinations that make me laugh. With the first ep, the lyrics were mostly made up of catchphrases from my dad, or bizarre things my mom would sing to me as a kid. I reworked them to fit into our songs. With the new Ep, the words are pretty descriptive of situations I've been in or some dark/ odd interactions I've had. The repetition is something I think helps paint the mental images I'm going for.

Johnny Sneeze: Hana writes almost all of the lyrics,and most of the time they're out on top of something that we're already doing and see if they fit.

Q: What is the creative process behind the music? Fat Piggy is lo-fi drum machine driven with a variety of guitar tones and electronic elaboration, but all very minimal. What goes into creating the music? Is it treated almost as a soundscape with your words added or do you create together?

Hana Ko: Our writing process is usually pretty on the spot and in the moment. We get together and the songs usually just pop out and we go with whatever feels right.

Johnny Sneeze: I'm not sure if there really is a whole lot to the creative process, haha. We usually go into our practice space and start playing something, and it works most of the time. That spontaneity is something that we like to bring to our love shows. There are a good amount of our songs that have a level of improvisation in them.

Q: How is the recording of your new album different from the recording of Fat Piggy? Did you go into a studio or is it self-recorded? Do you record live? Or do you layer the various sounds and vocals?

Hana Ko: We recorded both albums with our pal Joe Bazydlo in Connecticut. We don't add a ton of effects or anything. I think the recordings stay true to how we actually sound which is super important to us.

Johnny Sneeze: We recorded the new album identically to Fat Piggy, the only difference really being that we had a few new pieces of equipment. It was recorded at our friend's house in CT, dubbed "the Cigarette Factory." All the songs were recorded separately and layered together.

Q: Freakbag plays out live very often. Do you view yourselves as a live band first with some recorded songs? Or do you see yourselves as a recording band that plays your songs live?

Hana Ko: We are 100% a live band first and foremost!Most of the reason we started Freakbag was so that we could play shows! It's way more about the experience and performance for us, the actual tunes being secondary. I think it's about being in the moment and feeling that raw energy. I sometimes see bands play who look bored, and I really wanted Freakbag to just be about fun. So our goal was to have an entertaining live show, I love to jump around and freak out and yell. That doesn't really come across the same way on the albums.

Johnny Sneeze: I definitely feel like we are a live band first. The recordings are a fun document, but I think the feeling of our live show isn't always there.

Q: All of your songs on Fat Piggy are very short and concise. What does writing short music do that is lost in longer songs?

Hana Ko: I don't have the attention span for long songs or long sets for that matter. We like to keep it simple, short, catchy and to the point. I thinks it's fun to be like "what's that? What's happening!?" And then its abruptly over ! Haha.

Johnny Sneeze: Once you get the point across there isn't too much else you need to do. It's also fun to write a bunch of new songs all at once, which is more achievable with shorter songs.

Q: Freakbag kind of strikes me as a celebration of some kind. What are you guys celebrating?

Hana Ko: We are celebrating definitely! It's crazy to me that I can yell about pigs, and dance around and not get made fun of. It's a celebration of all the freaks!

Johnny Sneeze: Being your own weird selves! Not conforming to anything and getting what you want for yourself out of life.

Q: Who are the people in your band? Where are you playing live in the month of June (when the article comes out)? When and where can people find the new album?

Hana Ko: Hana Ko and Johnny Sneeze. It's always just been us as a duo! The new cassette will be available at shows!

Johnny Sneeze: This band is made up of Hana Ko and Johnny Sneeze at the moment, hopefully we might be able to expand at some point. You can find the new album on our bandcamp page or pick up a tape at one of our shows.

Q: Any fun live stories from the world of Freakbag? Be vivid.

Hana Ko: My favorite story is from we went on tour last fall. We get to Friendship Mountain in Jersey and it's been raining for days like torrential downpours. The place is a little basement spot and water had been coming down hard into the bulkhead and there are these huge puddles in there. It didn't matter, everyone still piled in all soaking wet. There were some electrical issues going on at this point and things were zapping. So when it came time for our set we had to reconfigure our setup a little so my mic wouldn't shock me! Haha anyways, we start playing and our pal John Guttschall, who puts on the shows there, starts freaking out during our 1st song and dives right into this massive puddle! He started like swimming/ dancing/ thrashing around and he's totally soaked in this puddle. It was wild.but it got everyone excited and splashing around more. Definitely a memorable night!

Johnny Sneeze: I think out of our live shows, one of my favorite memories was playing in front of a bunch of little kids at the Ricky Rainbow show at Black Box. We were asked to play one song, and we hung around the show until It was time for us to play. It was really awesome seeing a bunch of young'uns really digging our song and dancing around while their parents sat in chairs and kind of looked annoyed. We were even drawn as cartoons for a little coloring book they made for all of the kids.

You can find Freakbag’s music here.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Josh Cournoyer’s I&R brings an all-star line-up back home

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The first word that comes to mind with this one is earnest.

Dave Savage launches into Affinity & Beyond with an energy necessary to just get on with it. Equal parts stand-up bass driven folk and riff driven pop-punk move this record along as Savage’s words explore his own world at his own speed. Mixing self-reflection with necessary calls to action, this record strikes me as restless in the best way possible. Not content to stick around with the same kids on the same block getting on with the same bullshit, Savage moves to occupy new space with anything he can. Full band or a strummed guitar both work as movement behind Savage’s words allowing the search for meaning to be the drive behind each song.

Affinity & Beyond stands as a manifesto or a howled rant drawing Savage’s line in the sand against the status quo.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

High School Never Ends: Manifesto (Strategies, Goals & Process)

My goal in writing my essay was to fully thrust myself down a rabbit hole of thought. Emboldened with more questions into human nature than anything else, I found myself preoccupied with just what makes us hit that post button. What is the real significance of all this digital “sharing?”

Social media, blogs and other other free and available media outlets have created a universal platform for all people who choose to engage online. Sharing recipes on a Facebook wall, writing a personal blog, recording videos or podcasts or developing a form of activism all are inevitably tied to a certain level of popularity or active seeking of popularity. While the sentiments of people wanting to be noticed or have their work noticed in some way may have always existed, the free and open internet as it exists today has really elevated these sentiments to much higher levels.

Everything is hyper-paced and universally available around the clock. One cannot escape the pull of social media and it has become a parallel dimension to our three dimensional world. My goals in this essay and social experiment project were to seek out and provide empirical evidence that digital authorship is nothing more than a deeply rooted desire to belong. It is a call to anyone who will listen that we are here to create and those creations need validation.

This essay was designed dig deeper into the nature of social media and digital authorship. With so many free creative outlets and platforms for “sharing,” I believe people have an inflated stake in these platforms to contribute and actively monitor just how important their post (in a broad sense) are. The opportunity here is explore what does creatively engaging on the internet (for any multitude of purposes) bring to us intrinsically by broadcasting so much extrinsically? If people are moved to share for the sake of monitoring who is seeing or supporting or opposing what they do, what will the new nature of authorship be? What are the varying degrees of authorship from one “like” to millions of followers? Are we actively community building by sharing? What does the ability to show support or rallying around a cause really say?

My essay seeks to connect research of scholarly work to a more personal take on what content (created, remixed or re-shared) generates the most feedback and what psychological effects are produced by sharing and subscribing to different kinds of content in a public display. Is the online-self nothing more than a fashion statement? Or is it something real?

The work process for this paper was devoted to searching for sources and constructing a social experiment to implement as a creative component to a this kind of meta-authorship. As I explored popularity as the root of all digital authorship, I myself had to embark on numerous elements of digital authorship that, in themselves, explored the very validation I wanted to nail down as the end-point of any public decision to post online.

From the selfie to the scholarly article, we are on desperate, far-reaching searches for connection, community and validation that what we create is worth the time of others and that what we do with our time is worthwhile. This validation is now instantaneously at our fingertips and as a result we have become followers of the very things we create.

The essay is for educators who foster authorship and for people who actively engage online in any capacity and to any end. The goal of the research and essay is to explore the nature of authorship in the context of popularity and self-branding. When we have students put work onto a blog or create a podcast there is the unspoken (or perhaps spoken) notion that people will hear this, it’s out there.

By being “out there” with our work are we just preparing our students to seek approval or recognition? Does sharing something point to a need for acceptance or validation? Does creating or liking a "activist" page show an intrinsic desire for social change or is it an extrinsic symbol? Nothing more than an advertisement of one's identity?

In an unexpected turn of events, I found myself exiting the rabbit hole in an unexpected space of wondering where the nature of authorship will go next. I have spent so much time thinking of where authorship stands today as a destination, that it only dawned on me in conclusion that our posts are threads in the very fabric of the young Internet itself. Each element we “share” is another stitch into something larger and as yet unrealized.

0 notes

Text

High School Never Ends: A Social Experiment

As a component to my project, I also conducted a short social experiment analyzing a variety of publications posted on Facebook in a one-hour span of time. After a week, I analyzed the posts and the conversations within posts in an attempt to compare levels of engagement on the posts. In short, I sought to discover what kind of post was “most popular?”

You may find a link to the slide presentation here. It is a compilation of my research.

Conclusions:

What becomes abundantly clear from this variety of post, at least in the circle of amassed “friends” I have on Facebook is that the more likes went to the more relatable posts showing expressions of cuteness, humor or personal triumph. The post of the grad-school meme, my dog and the Rhode Island Press Award post all generated not only the most likes, but also a healthy interaction in the comments and interaction within those comments.

It was found in this social experiment that it did not take much for a post to feel even somewhat validated. A single like offered some degree of someone’s out there connection, but those feelings were greatly amplified when a post generated more likes and public back-and-forth.

The posts I chose to publish and research represented middle-of-the-road posts that most people might make on a daily basis. No matter what the content of the post, a common factor was a desire for reaction and social interaction celebrating or acknowledging what I took the time to post. The sharing of the “How Fast We Buy a Gun” video was shared with no commentary from me. It received no “likes” and no comments. Maybe no one wanted to open a can of worms. I tend to think that people are more apt to assign validation if there is a level of buy in from the author. It seems that people gravitate towards the more earnest or funny posts.

Finally, this social experiment illustrates that the feeling of validation from people for something we create always feels better than nothing. A published work collecting dust is nowhere near as fulfilling as the outpouring of support and adoration for a cute puppy picture.

While the outward seeking of such validation and “popularity” is not inherently bad, it does tend to boil down most of our engagements to a base, almost instinctual gravitation towards recognition seeking. It makes one wonder if social media and the way we engage on it was meant for something more. Does digital authorship need be validated to hold significance?

0 notes

Text

High School Never Ends: Popularity and Engagement in the Digital Age

Everyone wants to be popular.

While this sentiment might not be outwardly expressed by many or overtly apparent in everyday life, there exists a deep-seeded need for validation and recognition. In the digital age (arguably starting with the first AOL Instant Messenger screen-names, MySpace profiles and Livejournal sites) this outward, public seeking of validation and approval has been at the core of every endeavor undertaken in the digital world of self-broadcasting, self-publishing and community entertainment.

Whether outwardly apparent to the post-er or not, every status update, photo upload, blog, vlog, reshare or creative work is a shared and curated element of self-promotion and self-branding that speaks to a need to control how people see who we are and recognize the things we stand for, create or “share.” Likes, comments, re-blogs and re-shares all amount to a point system, a personal catalog of validation that works like a checkbook ledger crediting and debiting the appeal of the creator.

People, hyper-aware of ideas on the spectrum of “going viral” to “trolling” post with total awareness of the weight they carry in the online sphere. Everything one “shares” is at its core a maintenance of an online persona, a way to lure people to think a-like or challenge people to debate with the intent of bringing attention to the very thing that was publicly created.

To exist on social media, in any capacity and on any medium, speaks to a personal need to be popular, accepted, validated and recognized.

Thus, I would like to focus on three key areas of 1.) personal creativity in a “friends” context, 2.) public personal creativity (blogs, vlogs, podcasts and websites) and 3.) activism to examine how public viewing, critiquing and collaboration have made virtually all forms of interaction on the media, at some level, an amplification of personal desires for popularity, acknowledgement and relevance.

I will attempt to articulate a unified nature to why we post what we post. What are we looking for in our digital authorship and will it ever be realized? Does our personal digital authorship have a point? Does our “shared” authorship matter if everyone’s an author? For what reasons does the “social media self” exist? Is there such a thing as post-popularity authorship?

Part I: Selfie

The selfie has become the poster-child for our digital times.

The sole-creator, sole-subject of a picture looks to show in the most blatant of ways, what “I” am doing. Check this out. While the selfie is not something everyone partakes in regularly while at the gym, at scenic locales or simply to show something unmissable in the moment, it does serve as a good starting point for the larger discussion of the role of popularity in social media. The selfie is a metaphor of the digital author in any form (including the selfie itself!).

In their paper Narcissism 2.0! Would narcissists follow fellow narcissists on Instagram?” the mediating effects of narcissists personality similarity and envy, and the moderating effects of popularity, Jin and Muqaddam (2018) point to a level of narcissism associated with and attached to selfie takers. They write that “selfies allow individuals to manipulate the angle of the shot, to be at the center of the frame, and to make certain poses and facial expressions that reflect the personality they wish to communicate. Social networking sites like Instagram and Snapchat provide filters that improve the quality of the image and digitally enhance the face by hiding skin-spots and controlling brightness. Hence, when social media audiences judge images where the source is self-centered, they naturally associate this self promotion with narcissism (Lee & Sung, 2016) and therefore perceive selfies as narcissistic behaviors (Re et al., 2016)” (Jin & Muqaddam 2018, p. 32). While the selfie remains one of the more obvious and self-centered forms of self-promotion on social media, the intent of the selfie is the same core intent that drives any singular post someone might make. It is a desire to outwardly “share” something with the expected viewership and feedback of a community in return.

Digital authorship, in all forms, is simply different reiterations of the selfie. The word count or perceived merits of “high-brow” creativity or the simplicity of the re-share does not take away from the core purpose of the piece of authorship: It is a way to be noticed and to reach a perceived audience.

Part II: Yourself, personally curated

Like a perfectly staged selfie of profile picture, how one portrays themself online through the things he or she shares speaks to the unique ability to self-create and self-curate our own online perceptions. Kurt Vonnegut once wrote, “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful what we pretend to be.” This has never been more true than in our digital age and in regards to the task of personal digital authorship.

The act of wording a Tweet or choosing a recipe to share or choosing a cause to “like” all stems from the intrinsic knowledge that this information will be seen. The online persona is a sum of its digitally authored parts and it is responsive to the input of other digital authors.

Essentially, digital authors are in constant flux, tweaking, branding and altering digital personas to appeal to approval or recognition from online communities. The digital self is not static, it is constantly malleable to changing trends and events. In their study of different types of Facebook profile pictures, Wu, Chang and Yuan (2015) point out that “people use the internet to explore themselves. That everyone has two different entities; ‘true’ self and ‘actual’ self have been proposed before (McKenna, 2007). The user is highly motivated to project himself in the best possible way in the virtual world (Emmons, 1987)” (Wu, Chang & Yuan 2015, p. 881). This differentiation between the “true” and “actual” self speaks directly to Vonnegut’s “pretend to be” self. The words “true” and “actual” could just as easily be replaced with “digital” and “real-world” self and with that we could even branch those selves further!

Joachim Vogt Isaksen (2013) writes that a “person’s construction of an ‘imagined self-image’ is done unintentionally. We are not consciously aware that we often try to conform to the image that we imagine other people expect from us” (Isaksen 2013). One mirrors what he or she thinks will be acceptable to others and creates a version of themself accordingly.

To consider what elements of digital authorship show about our “best possible projections” is to consider the implications for our choices of what we show. It is worth noting, how absorbing the digitally authored, online self can be. Even in the midst of navigating real-world situations, the parallel Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, blog or other social platform sits ready to show new forms of validation for something shared. Who hasn’t scrolled through Twitter on the subway? To post a photo is not just to post a photo. To post a photo is to monitor the popularity of that photo in real time. What is the fallout from that photo? What is the impact of that photo? When does following analytics for a given photo cease being something worth looking at a smartphone for?

Isaksen (2013) points to American sociologist Charles Horton Cooley when he asserts, “[the] looking glass self, states that a person’s self grows out of a person’s social interactions with others. The view of ourselves comes from the contemplation of personal qualities and impressions of how others perceive us. Actually, how we see ourselves does not come from who we really are, but rather from how we believe others see us” (Isaksen 2013). With Cooley speaking to us from the turn of the 20th Century, it is easy to see how this idea of “self-image” has become hyper-edited and hyper-curated in the digital age.

While in person one might mimic body language subconsciously to gain someone’s favor, the world of back-and-forth digital authorship has allowed people to spend time and put great care into the maintenance of exactly who they are through their authorship. Shows such as MTV’s Catfish are built on the whole premise of people completely mirroring to the point of assuming someone else’s identity just for the sake of validation.

A post is more than a post, it’s an established ecosystem.

The point is not about the post. The significance lies in the life that takes shape around the post. The discussion or feedback or “virality” of the post is more important than the post itself. It is the cosmos that forms surrounding the post that gives the author meaning, feelings of validation and a reason to continue engaging. The post, no matter what it was, gave life to something.

That’s creationism.

Part III: You be an author while I be an author.

To be a digital author is to engage in “correspondent authorship.”

The act of writing a post and then responding with a gif is a case in point of back-and-forth authorship. While a face-to-face conversation is built around the moment, social cues, pragmatics, situations, visual and auditory stimuli; the act of being a digital author allows for wait time between interaction. In this way, the only way to respond to one’s online publication, even one so simple as “Love shopping at Aldi!” (Who’s my audience with that line? Why’d I say Aldi? The irony!) would be met with a considered and measure expression in return. The act of even considering whether to “like” a post carries with it the weight of realizing that the “like” will be seen by the author and that the “like” stands for something.

That “like” stands for a person and everyone can see who they are, everyone can think about why they “like” it and everyone can judge them.

Correspondent authorship, even between “friends” on Facebook is public domain. This is a central idea to the popularity drive behind every social media interaction. Companies like Facebook, Twitter or Tumblr afford the user a free service and all-important “wait-time” to express themselves. The promise of millions of other users having access to view and consume what we say or do, whether that many people actually engage with our published material, is enough to give everything we post, say or articulate a literal “pause.” Ranney (2015) writes that “the ability to control the dissemination of information and monitor self-representation in digital contexts helps individuals develop positive impressions among others and cultivate the esteem of their peers (Walther, 2011). Thus, information and communication technologies facilitate social and emotional adjustment by encouraging individuals to be more careful and deliberative in their digital interactions and behaviors than they are in their face-to-face interactions” (Ranney 2015, p. 4). This act of being “careful,” the momentary finger-hover over the enter key is our brain working not as a conversationalist, but rather as creator, editor and publisher of our own persona, hyper-aware of how the thoughts put to publication might play out.

And that’s just in the person-to-person interactions!

The things we choose to post and the multitude of other posted fragments, whether it be a Pinterest board or Instagram feed or news site with attention grabbing headlines, all feed into our ambient awareness. According to Levordashka and Utz (2016), “Ambient awareness can be defined as awareness of social others, arising from the frequent reception of fragmented personal information, such as status updates and various digital footprints, while browsing social media. “Ambient” emphasizes the idea that the awareness develops peripherally, not through deliberately attending to information, but rather as an artifact of social media activity” (Levordashka and Utz 2016, p. 147). The act of mindlessly scrolling through Instagram after a long day of work is actively working to develop ambient awareness of tens or perhaps dozens of people mathematically chosen to appear for one’s viewing pleasure. This ambient awareness informs us of trends, events or ideas worth further investigating, engaging with or forgetting about.

If enough people post about something, it’s going to get noticed.

In their study of “ambient awareness” on social media platforms, Levordashka and Utz (2016) used questionnaires to assess the extent to which people became aware of information in their networks just by browsing through a Twitter feed. Levordashka and Utz (2016) wrote the “results of this study show that people experience a sense of ambient awareness towards their online network. More importantly, they were able to recognize and report information about individual people in their network, whom they know only through the microblogging platform Twitter” (Levordashka and Utz 2016, p. 150).

Just as we have become accustomed to “scanning” for information, so too has our awareness of our social, political and professional circles become crowd-sourced. To just browse through what friends are posting on Facebook on a given night offers not just close friends, but acquaintances, ads and other algorithmically driven sponsored content based on the things we choose to publish. Thus, our acts of authorship are motivated to determine what social, political or professional circles we both see and pop up in.

Levordashka and Utz (2016) go on to conclude,“We demonstrate that browsing social media and frequently encountering various social information allows social media users to gain awareness of what is going on in the lives of people in their online network” (Levordashka and Utz 2016, p. 154). To engage on social media as an author and as an author on someone else’s authorship is further created in the context of being watched in a “fishbowl” so to speak. To engage on social media is part creation, part mathematical equation and part right-place-at-the-right-time all stemming from the initial desire to be noticed.

Whereas in person one must cultivate who they are in a fully dimensional way (emotionally, socially, physically), the digital world has been left as a place to write, edit and re-edit our memoirs in real time, see who’s reading it in depth and be intrinsically aware of the many others “window shopping.”

Part IV: Social Activism…there’s a brand for that

Social media has made social activism click-friendly.

To be an activist does not require physical action only intellectual action and a willingness to be vocal. In this way, activism in social media circles is kind of like comparing bumper stickers. There is a certain awareness that a “like” to an organization, whether it is Black Lives Matter, the National Rifle Association or Greenpeace, proclaims publically what one stands for.

Furthermore, to be an activist on a platform like Facebook, to “like” a page, offers a scroll bar of like-minded organizations, all with the same goal in mind, more likes and more clout that translates to more “likes” for the liker from the kind of people they want “liking” their posts.

Fichter and Avery (2012) write, “Having power and influence, making the things you advocate happen: This is the essence of clout. Does clout matter? Yes. On different issues, at different times and for different reasons, everyone wants their voices to be heard and their points of view acted upon, or at least understood, acknowledged and validated in some manner” (Fichter & Avery 2012, p. 58). This idea of clout puts community, social, political and grassroots organizations into the interesting space of brand management in order to achieve change. At some point, maybe around 10k “likes,” an organization enters a space of brand recognition that affords it the ability to market itself to people as a kind of “badge of honor.” Social movements become a way to express oneself without showing anything more than a copyrighted title and font.

In many ways, this appeal to broad popularity in a social media platform (soft activism) becomes a gateway to more concrete forms of activism such as giving money, protesting or voting (hard activism). In a study done on whether civic activism online made young people dormant or more active in real life, Milošević-Đorđević and Žeželj (2017) found that “when tailoring policies to

engage young people in civic activities, one has to have in mind different platforms and different topics; making them engaged in one type of activity makes it more probable that they would engage in others, making them engage in “soft activities” makes it more probable that they would engage in “hard activities” (Milošević-Đorđević and Žeželj 2017, p. 118). Therefore, it becomes essential for an organization to develop brand appeal and clout through activism and a key way to do this is to stand for something that people can show publically and let it, in turn, stand for who they are.

A drawback to the click “like” approach to activism lies in the “browser” nature of how we consume information online. To get into the nitty-gritty details is simply not something everyone has time for, so to “like” something one stands for places a level of trust in the organization to promote an imagine that maintains the cultivated imagine one hopes to achieve by advertising their “like” for that organization.

Ranney and Troop (2015) explore how this at-a-distance approach to social interaction leads to disconnection when they point out that “information and communication technologies (ICTs) limit the number of non-verbal social cues available during social interactions (i.e., facial expressions, vocal inflections, body language; Lee, 2004; Tanis & Postmes, 2003; Walther, 2011), which in turn reduces the total amount of observed information that is exchanged during interactions. The consequence is that ICTs may reduce the total amount of information exchanged, including the ability to convey one’s emotions, revisit topics, and discuss topics in detail” (Ranney & Troop 2015, p. 64). This lack of information exchanged directly correlates to the Trump-era we find ourselves in. The “like” of something Facebook recommends we like or the “follow” we give to someone Twitter says we should follow supplants the way one explains themselves, relying instead on social crutches to explain their views or personality for them through shares or re-tweets.

In 2016 people could go online and like a page proclaiming, “Make America Great Again,” they could buy a red hat and wear it and in those few words, so much could be said. Was it a movement? A feeling? A trend?

Whatever it was, people could share it, their “friends” could “like” it and their views were validated. The kicker was when those “likes” turned into mobile votes.

Instances such as this, mass movements based on catch-phrases and gut-impulses, is a natural conclusion to an online, social culture based on self-promotion, fast, bountiful information and limited time to consume or articulate stances, viewpoints or feelings. There lacks a need to explain one’s post if it is someone else doing the explaining. The digital author simply gets the credit for sharing, not articulating and the greater the ecosystem of engagement created, the greater the success.

If something feels right, why not share it and see who reciprocates those feelings?

Part V: Moving On

As an avid digital author in numerous forms myself, it is unclear whether there is a remedy to the popularity driven social authorship or whether there even needs to be a remedy. In essence, is being driven by popularity wrong? The moral implications of why we engage on social media aside, it can be asserted with confidence that the vast majority of our social, digital authorship through personal posts, blogs, vlogs, podcasts or other forms of creative publication is driven by a need for validation within a community or by a more open-public audience.

Validation in the form of debate-seeking trolls or likes or upvotes all add to a subconscious (or conscious!) tally of who sees our stuff, who likes it and who values its creation in the first place.

In short, we are a large part of each other’s entertainment, so we’d better have evidence that we are entertaining!

Ranney (2017) in his study of adolescent social interaction on the internet as a means to maintain social hierarchies, points to the growing influence of digital societies on social interaction. Ranney notes that “socialization through information and communication technology (ICTs) is so pervasive that, compared to 35% adolescents who report socializing face-to-face outside of school, 63% of adolescents text their friends daily, 39% talk with friends on cell phones, 29% message friends through social networks, 22% communicate through instant messaging, and 6% email their friends daily (Lenhart, 2012). Although time spent in school and in-person gatherings with friends remain important for adolescents’ social and emotional well-being, a majority of the social interactions that peers have with one another during adolescence is currently taking place in digitally mediated contexts” (Ranney 2015, p. 2). This time spent in digital social circles points to a need to fully understand and embrace what drives acts of digital authorship, come to terms with the underlying reason people are engaging online and decide whether “online” is ever meant for something bigger; driven by creations that are less self-serving.

Despite researching adolescents, I would not expect an adult sample to look much different in terms of time spent in digital realms. An adolescent posting about secret levels in a computer game and a middle aged man posting a cat meme are both driven to publish material for the same reasons; recognition and validation. It’s almost like a mantra.

Thus, as with anything else, attention is the catalyst for what one chooses to do. Where we place our attention is where we place value and seek to find quality.

Tiffany Shlain (2017) points out that “attention is the mind’s greatest resource”. She goes on to picture “the Internet, like the developing brain of a child…in a rapid phase of growth and change” (Shlain 2017). Like a small child, countless synapses are forming as the Internet grows in real time. More than being just “along for the ride,” we are active builders in the unseen and unrealized scope of what the Internet will become. Our acts of digital authorship, while being currently driven by popularity as a catalyst to create might need to become something more empathetic or humble if we hope to see social media and digital platforms become more altruistic than they appear to be. If Facebook’s recent rebrand as something “pure” has shown us anything, it seems we might be turning a small corner towards seeing social media in a different light.

There’s more to all of this than just “sharing” in different forms. I’m sure of it.

“This means that just as we must be mindful in how we nurture our children’s minds,” Shlain notes, “we must also pay careful attention to how we develop our global brain” (Shlain 2017). Our information and our authorship is shared content in the public domain. No matter what the privacy settings, someone else has access to it. It is a building block. It might feel insignificant or goofy or even useless and futile, but it is valuable information that informs a larger design. With the role of “builder” rather than “user” in mind, one can begin to envision a larger calling in the name of global consciousness and motivation behind digital authorship. One begins to not just be a personal creator, but a contributing creator. One is part of a larger one.

On the other hand, maybe a good, well-timed meme is as good as it gets.

Resources

Fichter, D. d., & Avery, C. c. (2012). Tools of Influence: Strategic Use of Social Media. Online, 36(4), 58–60.

Isaksen, Joachim Vogt. (2013). The Looking Glass Self: How Our Self-image is Shaped by Society. Retrieved April 17, 2018, from http://www.popularsocialscience.com/2013/05/27/the-looking-glass-self-how-our-self-image-is-shaped-by-society/

Jin, S. v., & Muqaddam, A. m. (2018). “Narcissism 2.0! Would narcissists follow fellow narcissists on Instagram?” the mediating effects of narcissists personality similarity and envy, and the moderating effects of popularity. Computers In Human Behavior, 8131–41.

Levordashka, A. a., & Utz, S. s. (2016). Ambient awareness: From random noise to digital closeness in online social networks. Computers In Human Behavior, 60147–154.

Milošević-Đorđević, J. J., & Žeželj, I. z. (2017). Civic activism online: Making young people dormant or more active in real life?. Computers In Human Behavior, 70113–118.

Ranney, J. D. (2015). Popular in the digital age: Self-monitoring, aggression, and prosocial behaviors in digital contexts and their associations with popularity (Doctoral dissertation, North Dakota State University).

Ranney, J.D., & Troop-Gordon, W. (2015). Problem discussions in digital contexts: The impact of information and communication technologies on emotional experiences and feelings of closeness toward friends. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 64–74.

Shlain, T. (2017). How The Internet Is Like A Child’s Brain. Retrieved April 17, 2018, from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/brain-power-film-and-ted-book_b_2083785.html

Wu, Y. w., Chang, W. i., & Yuan, C. d. (2015). Do Facebook profile pictures reflect user’s personality?. Computers In Human Behavior, 51880–889.

#edc534#selfie#long reads#essay#philosophy#education#media#digital#Digital Literacy#computer#social media

0 notes

Text

Facebook Owns You

This article was published on Mic back in 2013. It popped into my head recently.

Adam Hogue

| June 25, 2013

You can walk away for a year, two years, live out in a shack in the woods but there will come a day where you find yourself wanting to check back to Facebook.

No one can stay away for long. This is how we live now.

At least, that’s the general consensus a number of “living without internet” experiments have arrived at. The internet, namely social media, is something that we have bought into in a big way and there is little hope of escaping its gravitational pull. In three words, Facebook owns you (and will sell you).

Our society is becoming increasingly invested in our social media, to the point that we are finally wondering when the pendulum will swing back. Some are arguing that social media is already in decline with younger generations looking to return to simpler, pre-status days where eye-contact on the street and tag-free photos were the norm. But, it is unclear whether such a “disconnect” is possible. In a sense, we are in The Matrix already.

Over the past year, a few stories have turned up from notable writers that explored “unplugging.” While each story offers a different perspective on stepping back from being a “plugged in” 20-40 something, they all share a similar fate in the end. All of the writers could not stay away from the technology they grew with, while cutting back was feasible, a complete disconnect was impossible to sustain.

Let’s start with the case of The Verge’s Paul Miller.

Miller was paid by The Verge to leave the internet cold turkey for a full year. No internet at all. Initially, Miller felt his quality of life get better. His attention span increased, he could read hundreds of pages of Greek literature in a single sitting, he was having better conversation and he was more attuned to maintaining relationships. But, over time, that zeal of life faltered and eventually he was back in the same pitfalls that he had once blamed on the internet.

He realized the internet was not something that distracted from “reality.” The internet and the way we connect is our reality. It’s our world now, take it or take it.

A year later, the internet didn’t seem so bad.

But, while the internet might be the reality we live in. There are certainly levels to the extent in which we engage. For instance, I’m a one tweet, one status a day, one essay a week guy. I read my news online, but otherwise, I don’t find an intrinsic satisfaction loitering online. Granted, I don’t yet have a job that demands I do…yet. But, in the case of writers (writers much more famous than me) the internet is a life-blood. It is the source of promotion, connection with fans, and maintaining a brand. It’s the way the business works.

In my freshman year at Keene State College, I watched Baratunde Thurston of The Onion perform stand-up, shortly thereafter I began to follow him on Twitter and I have been amazed ever since at the level of tweeting one person is capable of. These days he is the bestselling author of How to be Black. He is also a prime-example of what I would call a “plugged-in” person. What started as a need to promote and engage, became an unweeded garden of social networks, applications and general keeping up in a little bit of everything.

But, not too long ago, Baratunde took a slightly lighter, but still bold month away from the internet for the sake of his sanity and he wrote a great essay about it. While the Miller experiment ended in him coming full circle, realizing the internet does not change the person, Thurston arrived at a much more light-hearted, optimistic view of his break. He noticed the world more, he was unafraid to try restaurants on sight alone and he found himself in a state of freedom from those things he once felt obligated to contribute to.

Suddenly, not tweeting made him not care if people were reading what he said or not. This is a feeling that anyone who has taken even just a few extended days away from Facebook is no stranger to. If you don’t think about it, it doesn’t matter anymore. He was engaged in a living environment for a change.

But, ultimately, he knew he had to eventually return.

We find ourselves in a plugged-in world whether we truly enjoy it or not. Perhaps a Facebook friendship is not a substitute for a person-to-person friendship; but it is what we have created and cultivated. With our social media we have the ability to be ever-present to everyone, but at the cost of being truly present to the few people around us.

A final case to consider of severing all internet ties concerns only Facebook. Katherine Losse was an employee of Facebook who was one of the few women with a liberal arts degree to make it so far up the ladder (for a while she was Mark Zuckerberg’s personal ghostwriter).

In a piece by Craig Timberg for The Washington Post in August 2012 (is that too out of date for our internet age?) we meet Losse in the town of Marfa, Texas. She is physically cut off from the world, her Facebook is deactivated and she is working on a book. She argues that Facebook is playing in very “touchy territory” with the vast amounts of information they and other social media store.

The fact that we actively and willingly trust our information to these free servers and then demand our privacy or feel betrayed when we find out this information is being accessed and stored by people other than ourselves is reason enough to feel that a great social media walk-out should almost be guaranteed in the future. It is this trade-off that led Losse away, out of the Silicon Valley, to a trailer in West Texas.

But, like all the other post-Walden “unplug-gers,” Losse now finds herself, reluctantly, back on Facebook as a means to promote her brand. Like the rest of us, she’s in the make it big or die-trying youth of life and the internet is the only frontier people are paying attention to.

We’ll always come back to our social media.

In a bit of an ironic twist, I posed the question, “Any thoughts on leaving social networks?” as my Facebook status for this article. The response falls in line largely with those that tried to disconnect above. It is a varied and objective field. For most, Facebook and social media is a lifeline for engaging, learning, business, connection and promoting. It is not perfect, but it is a reality. It is a curated diary that will survive longer than we ever will on this Earth.

Whether we are ready to admit it or not, social media is a tangible part of our society. It is a world-wide nation that we have a personal stake in … our identity. To disconnect from social media or the internet as a whole is to erase one’s self from a part of society. However, there can still be be valuable lessons gained from moderation and even severely limiting one’s presence from social media platforms in exchange for simply an e-mail address.

Our information and the parts of ourselves we leave on the internet binds us to a 21st century facet of the world we live in. As I alluded to earlier, we are giving ourselves to social media for nothing, in exchange for feeling a sense of online connection that may or may not be genuine, but, as Paul Miller illustrated, is better than no connection at all.

As a collective, multi-generational, world entity we are deeply engaged in our social media. Our information is there and it is not going anywhere soon. Perhaps, in the future we will see the world of Facebook, Twitter, and blogs disappear; but that will take considerable time to undo.

For the time being, we are products of our social media and we will never be away for long.

With that being said, for a credible, well-versed source on 50 years disconnected from social media, talk to my dad.

It’s not so bad.

0 notes

Link

Feel free to enter the Padlet, listen to my reflection and contribute to the conversation yourself. I would love to here your thoughts in any medium (Padlet permitting) you choose.

What do places mean to you?

What’s a shared story?

How can memories be crowd-sourced?

#edc534#Digital Literacy#digital authorship#digital media lab#renee#hobbs#URI#podcast#reflection#padlet

0 notes

Text

Relax, This is Only a Remix

Somewhere in the ether an idea is born.

From some deep (or not so deep place) a creative impulse jets it’s way to the surface. Perhaps it’s a lesson plan idea or a line of a song or a manifesto waiting to be pounded out on the keyboard. Wherever that idea came from, it’s yours. It’s yours to create, yours to nourish, yours to contribute.

At its core, this is how I have come to interpret “fair use.” From somewhere an idea came, but, regardless of where it was born from, the genetic make-up of that idea is an imprint that is the sum of countless parts that are surely the copyrighted material of someone else’s bright idea.

So it goes.

While the idea of giving money and due credit to artists or creators or innovators and the protection of their intellectual property is a fundamental right, it is unrealistic to consider that every single utterance of said work must result in an infringement on the said property. The Media Education Lab (2008) defines fair use as “the right to use copyrighted material without permission or payment under some circumstances—especially when the cultural or social benefits of the use are predominant. It is a general right that applies even in situations where the law provides no specific authorization for the use in question—as it does for certain narrowly defined classroom activities” (Media Education Lab 2008, p. 1).

In essence, ideas must be allowed to take shape unhindered by restriction as they will almost inevitably be built upon the material of other ideas. Aufderheide (2012) points to “the prizing of transformativeness (repurposing, not just re-use) as key to deciding fair use” (Aufderheide 2012, p. 6) and the confidence fair use can afford creators to pursue their ideas wherever they may lead and to whatever end is in sight.

Aufderheide (2012) goes on to explain that “Fair use applies to all of a copyright owner’s monopoly rights, including the owner’s right to control adaptation, distribution and performance. It applies across media (for example, music, video, print), and across platforms (analog, digital). Part of U.S. law for more than 150 years, and especially in recent decades, fair use has become a crucially important part of copyright policy. It is a core right; it is part of the basic package of freedom-of-speech rights available under the Constitution” (Aufderheide 2012, p. 7). To this end, fair use is an enabler of progress and process to create.

One might argue that no idea is truly original.

Indeed what someone like Joseph Campbell or Kirby Ferguson (2015) brings to light is the idea that archetypes and “remixes” of existing media begets new media or ideas advanced in a new direction.

Nods in film or music to familiar styles or even specific moments awakens something in the viewer or listener that can help them to see the point trying to be made. Ferguson (2015) titles his series on Vimeo “Everything is a Remix” and in the process of breaking down what makes something a remix must essentially remix and re-represent existing media to make his point. Does this make what he does infringement or unoriginal? Of course not. Ferguson (2015) using clips from J.J. Abrams to illustrate how J.J. Abrams is essentially a “remix” artist involved hours of sorting through and remixing J.J. Abram’s own “remixed” work in order to show how its a remix, juxtaposed with the remix of the “original” work Abram’s work is said to “remix” in the first place.

In order to point out that “everything is a remix,” Ferguson (2015) himself must rely on remixing himself to make his point thus proving his point through the act itself. Think Don DeLillo’s “most photographed barn in America” from White Noise. Everything is a picture of a picture that is already in our minds from somewhere.

The Media Education Lab (2008) notes that “copyright law does not exactly specify how to apply fair use, and that gives the fair use doctrine a flexibility that works to the advantage of users” (Media Education Lab 2008, p. 6). For someone like Ferguson (2015) or Abrams or Kanye West or any Youtuber to do what they do, this flexibility and murkiness of what exactly “fair use” specifically means lands the favor on the side of the creator and lays to rest what Aufderheide refers to as the “romantic notion of authorship.” That is, that the creator is the sole creator and sole-owner of their content.

So hands off!

Aufderheide writes, “filmmakers interviewed here also balanced the ‘Romantic ideal of the author’ with the realization that, at least for documentary filmmakers, new work that uses existing work is also creative and should be valued. The realization that the law did not merely permit but encourage the re-use of copyrighted work for the creation of new work, while a new idea for many, was an exciting one that challenged their surface assumptions about authorship” (Aufderheide 2012, p. 11). Thus, authorship is a give-and-take collaboration and with each new, almost certainly free contribution to the world wide web, that give-and-take collaboration and ability to chunk and rehash other people’s work for new hopefully ingenuitive purposes grows exponentially.

As long as the end is something altogether transformed, the ability to utilize the copyrighted work of others is free and fair game. The Media Education Lab (2008) points out that “despite longstanding myths, there are no cut-and-dried rules (such as 10 percent of the work being quoted, or 400 words of text, or two bars of music, or 10 seconds of video). Fair use is situational, and context is critical” (Media Education Lab 2008, p. 15). Thus, the idea that comes from the ether can be allowed to exist freely.

Just be ready to defend it.

Resources

Aufderheide, P. (2012). Creativity_Copyright_and_Authorship. In D. Gerstner & C. Chirs (Eds). Media authorship. New York: Routledge.

Ferguson, K. (2015). Everything is a Remix: The Force Awakens. YouTube.

Media Education Lab (2008). Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for Media Literacy Education.

#edc534#university of rhode island#Digital Literacy#digital authorship#digital#copywrite#clarity#essay#long reads#fair use#renee#hobbs#digital media lab

0 notes

Audio

A roomful of family, a photo and a composed story about a place.

1 note

·

View note

Text

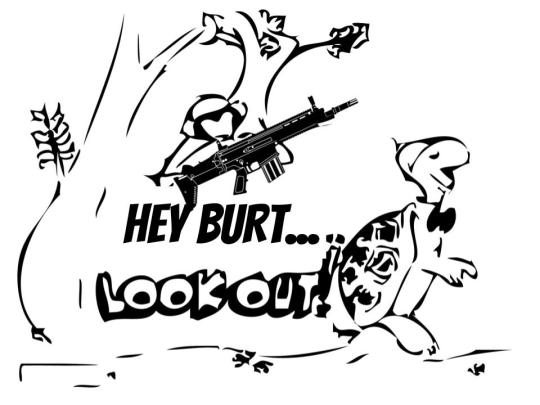

LEAP 2: Duck and Cover

The Atomic Age and the Cold War will forever be associated with duck and cover drills in schools. Students were instructed to crouch down and protect themselves from impending danger- collapsed roofs, flying debris, the inevitable results of an explosion. Luckily for American school children, their rehearsals were all in vain. The Cold War ended without ever becoming warm.

youtube

There is a war on American soil today. Mass gun violence has sparked a need for children to prepare, once again, for the worst.

My partner and I created these images to draw comparison between the Cold War era drills and the modern day lockdowns. It is absolutely unacceptable to us to think that our nation’s children face the daily threat of violence and death, as they have in times of foreign wars.

These images were created using Photoshop and Google Drawings. Our process began by searching for historical and more recent images using a Google Image search. Images were added to a shared Google folder. Historical images were selected in order to draw the comparison between nuclear war and mass gun violence. These images were copied and modified in Photoshop using the live tracing tool. Text was drafted in a shared Google document. Ultimately, my partner and I decided to annotate the original text that had captioned these images. We believed this would strengthen the comparison and represent the urgency of adopting lockdown procedures in schools while at the same time, revealing with a sense of irony that the more circumstances change, the more they stay the same.

By recycling, manipulating and annotating existing digital media from a bygone era, we attempt to reveal the seemingly contradictory ideas that these drills are both necessary to perform and, at the same time, altogether futile. The use of red marker over stark, Banksy-esque stencil motifs adds to the narrative of “updating” Bert the Turtle for more “modern” times by attempting to show a “work-in-progress” approach to the images. They remain unfinished and merely sketches of what could be, not what is.

Duck and cover is a metaphor for how our society has confronted mass gun violence. Rather than reform policy, we double down on how we will respond to the incident itself. As we practice intruder drills with our students in schools, we are assuring them that gun violence will continue. The only preemptive measures our policy makers are willing to take are to mandate rehearsals without adequately confronting the source of this violence.

Bert the Turtle, while seemingly a relic of the Cold War, has never been more timely. This project is an act of civic engagement and protest through digital authorship.

Resources

Rizzo, A. (Director), & Mauer, R. J. (Writer). (2009, July 11). Duck and Cover [Video file]. Retrieved February 27, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IKqXu-5jw60

0 notes

Text

Facilitative Instruction

A central idea to the readings this week is that media literacy can no longer be relegated as an extra-curricular subject or a talking point, rather, it must be built into the everyday lesson. Generally, students must be able to navigate digital media, manipulate digital media and use digital media for the explicit purpose of civic engagement that supplants the still-prevalent model of teacher-centric, teacher approved information being given and then tested upon.

This general model of education is bumping up against a digital world that grew exponentially in a relatively short period of time. Close to 20 years of (relatively) high-speed internet has created a parallel existence of accessible knowledge that current generations have grown up with and are able to use. Hobbs (2016) points to a need to empower to young voices through progressive, civic education that seeks to actively employ free, accessible knowledge for the sake of youth driven creation. Hobbs (2016) writes, "when young people discover a sense of agency from participating in a meaningful form of public communication, where their voices are part of a strategy to create social change, the impact can be transformative" (Hobbs 2016, p. 364). In Hobbs' view, digital media education and the ability to facilitate, aid and guide student-chosen, student centered pursuits is where the transformation in education lies.

Mihailidis and Gerodimos (2016) echo the sentiments of Hobbs in pursuit of the core dilemma this approach to digital media education presents when they write, "formal education has long struggled with how to build effective approaches to teaching about citizenship while being wary of the complex political, social, and cultural constraints that are embedded in pedagogical design and approval. Civic action that is seen as overtly political in some way is harder to justify as a learning outcome. As a result, the work of the literacies can be agnostic toward social justice, inequality, underserved populations or communities, and the role of civic voice as a change agent" (Mihailidis, P. & Gerodimos, R. 2016, p. 377). Along with pushing students into a space of active, real-world civic engagement comes a loss of ability to assess them in the formal, classic sense. To facilitate is seen as a release of power and authority that, to many educators, feels like a blow to self-esteem.

Thus, a component to transform practice in education rests in the ability to embrace civic engagement in digital culture from both youth and educator perspective with the same intent. Engagment in this digital culture "depends on the extent to which citizens learn to use media to step out of their routines and comfort zones, experiment, fail, innovate, interact, argue, and learn" (Mihailidis & Gerodimos 2016, p. 382). This applies first to educators in the classroom and then unto students. A teacher who is willing to step outside their comfort zone will find themselves working with students to create something new.

Resources:

Hobbs, R. (2016).Capitalists, consumers and communicators: How schools approach civic education. Mihailidis, P. & Gerodimos, R. (2016). Connecting pedagogies of civic media: The literacies, connected civics and engagement in daily life.

0 notes

Text

Ugly Betty and Affirmative Action

Artwork by Jeremy Ferris

Step 1: Google Morgan Jaffe

This was not an intention, but it was something that I noticed myself doing, almost, as if it was an action out of my control. A fluid and seamless scroll over to a new tab while Jaffe’s (2017) voice introduced her podcast, Burst Your Bubble, in the background, “Ugly Betty, a U.S. interpretation of a Latin-American telenovela...” (Jaffe 2017). While the podcast continued playing, I was typing her name, my mind half-heartedly in two places at once. She’s in Boston? Is she my age? Is she younger than me? Did she really teach in all those schools? Should I being doing something, anything differently?

The questions were all there, a second layer while the podcast droned on. It is is within this impulse that I find a necessary place to reflect on where I found myself. In a simultaneous moment, I was consuming information, questioning the credentials of the information and then returning to the information with a different perspective, in under ten seconds. I did not approach the podcast wondering who Morgan Jaffe (2017) was, but, there was a definitive moment where the need to know credentials, status, background and there they were and then, click, the window was closed.

While not coming from any deep place, this ability to instantaneously question and receive a gratifying answer to said question is a hallmark of our digital age. It was a sense of power or at least a sense of gratification. I felt more comfortable listening, I trusted or at least didn’t completely disregard the voice that was speaking, I had some sense of a person speaking with a background. I felt a sense of peace with being able to react to what I was listening to, it was no longer an unsubstantiated voice.

Following the Podcast and a listen to some of Jaffe’s (2017) other episodes, I felt more comfortable knowing who she was as a person. I started to anticipate her cadences, her responses and her stances. Jaffe (2017) is a quintessential “millennial” voice. She has views she wants to express, she knows how to create a platform to express her views and she knows how to market her expression into a form of quantifiable consumption. She can see the weight of her opinions in views, comments and subscribers.

Jaffe (2017) describes her podcast in this way:

“Burst Your Bubble is a podcast that combines racism, sexism, homophobia, and all of the other -isms and -phobias within our society and looks at them through a pop culture lens. From music and movies to comic books and games, hatred, bigotry, and ignorance seep into our everyday lives. What is important is to dissect it and discuss it, and not just accept it as something we can not process or change” (Jaffe 2017).

Hobbs (2017) reflects this sentiment when she writes, "asking questions can activate and deepen critical thinking and the practice of close reading and close analysis can be a powerful tool to understand how media are constructed and how media text construct reality" (Hobbs 2017, p. 62). While only surface deep, my initial questions about Jaffe were necessary for me to consume what she was saying, whether I agreed or disagreed with what she was about to say, I needed to know the source of the opinions I was receiving in order to decide if the argument she was presenting was worth my time at all. Was Jaffe (2017) a voice worth agreeing with or challenging?

The small questions that plagued my mind at the top of the podcast about Jaffe (2017) gave me a sense of who she was as an author. With a background in education and communications, Jaffe (2017) works as the General Manager of Boston Community Radio. Being a supporter of public access media in all forms, this allowed me to listen to Jaffe (2017) as a authority on the subject matter. Some other aspects of the podcast, the uniform intro music and use of original artwork by Jeremy Ferris for each episode further lent credibility to the podcast in my mind. It had substance. While only image deep, the branding and the hook of “challenging” assumptions was enough to not only catch my attention, but intrigue me enough to listen.

Step 2: Maintain judgement-free Zone, listen, make coffee

As with all other podcasts I have come to enjoy (Love + Radio, Radiolab and This American Life to name a few), the listener is brought to a familiar place with theme music and a hook from a recognizable voice. These elements make the podcast a welcome place to relax and listen to something. Jaffe’s (2017) Burst Your Bubble is no different as she introduces what Ugly Betty (the show) meant to people, what it did right and then, the hook before cueing the music. After celebrating the grounding breaking nature of Ugly Betty and what it brought to marginalized voices on network television, Jaffe (2017) “pops” the bubble when she says, “but it still has some stereotypes and problems of its own. Like the episode where Ugly Betty puts affirmative action in a negative light. I’m Morgan Jaffe and this is Burst Your Bubble” (Jaffe 2017). This “burst your bubble” moment is a predictable element of Jaffe’s storytelling style and it serializes the podcast in a way that allows the listener to predict her inserted opinion after laying out a seemingly noble, altruistic or otherwise positive element of pop culture. It is this moment that holds the listeners attention and elicits a response that causes them to listen to Jaffe’s argument.

In itself, Jaffe’s podcast serves as a method of digital inquiry that the listener can follow along with and, at the same time, must perform a meta-inquiry about Jaffe’s (2017) own inquiry.

Jaffe (2017) focused her podcast on one particular episode of the show Ugly Betty that took on the issue of affirmative action. Throughout the course of the 30 minute podcast, Jaffe (2017) works in what Hobbs (2017) calls the “theater of the mind” as she delivers an opinionated de-construction of the episode using clips from the show to link together her ideas regarding affirmative action, what the show got wrong and what opportunities were missed. Hobbs (2017) writes, “storytelling’s inevitable and highly attractive approach to oversimplification, through the creation of a hero, villain and victim, may distort our understanding of history by contributing to the fictionalization of history” (Hobbs 2017, p. 125). In Jaffe’s (2017) case, she is working to poke holes and offer a more rounded, gray-area view of pop-culture as we know it. Through her storytelling, we are offered only her take on things and are left to debate outside and apart from the speaker, in the real world, while her views are left recorded and static.

I suppose one could always tweet her their take.

For this reason, I purposefully suspended judgement during the episode to fully absorb Jaffe’s take on the episode. In this way, I attempted to approach the media as an independent listener, but also an open listener. While I support Affirmative Action and agree with general atmosphere of what Jaffe had to say, I also find myself adopting opposing viewpoints as a default when confronted with opinions. Even if the opposing viewpoints are not necessarily ones I believe in.

I believe one needs to be comfortable with having their views uncomfortably challenged or adopting uncomfortable positions, even in a hypothetical sense. Namely, playing devil’s advocate in one’s own mind. That is a level of vulnerability that is needed now more than ever. Media simply must be met with a challenge.

In a kind of double kudos, I commend Ugly Betty for taking on the issue of Affirmative Action in such a direct way. I have never watched the show, but even given the clips that Jaffe (2017) provided, I feel like Ugly Betty did make an effort to confront an issue calling it by its name and allowing different sides a voice on the issue. Furthermore, I feel like Jaffe (2017) should be commended for holding the show accountable for not taking the issue far enough. People of color, disadvantaged people and other stakeholders in this issue might interpret Jaffe’s message as either a rallying cry or something disagreeable, but, it should be generally realized when listening to a podcaster, a vlogger, blogger or even fringe “newscaster,” that they are representative of one viewpoint. It is up to the listener to discern their own take on the matter using the voiced opinion as either a catalyst or opposing force to move their position to more solid ground based on reason, research and articulation.

Step 3: Dig deeper, ask questions, rinse, repeat

Pangrazio (2016) defines "critical digital design" as a framework to operate within in order to both consume and create digital media. She writes, "critical digital design can be thought of as a deliberately political model of digital literacy in which complex and detailed understandings of discourse, ideology and power in the digital context are scaffolded. It aims to analyse the specific multimodal features of digital texts, as well as the general architecture of digital technology and the Internet, so that a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of these concepts is developed in the learner" (Panagrazio 2016, p. 172). With this in mind, it becomes clear that what Jaffe (2017) is doing to Ugly Betty, one must also do to Jaffe herself. While Jaffe (as an admittedly white woman) stands up for Affirmative Action and what it has done for disadvantaged people of color, she does not offer understanding or empathy for the clips she played of white people who sued universities from not getting in. Jaffe’s (2017) values align with the plight of the “Ugly Betty’s” of the world, but she does not see a gray-area in such circumstances.

Furthermore, Jaffe (2017) fails to recognize the work and hard decisions the writers of Ugly Betty must have made to air an episode that dealt with Affirmative Action in such a head-on way and with care given to opposing sides of the issue. While “it was a different time” or “it was good for its time” arguments do not always apply, I think they do in this case. I feel like Jaffe omits an olive branch given to writers and producers of Ugly Betty in favor of doubling down on her own strong opinions, as right as they may be. Did Jaffe (2017) consider Salma Hayek’s work as producer of the series (Barreiro 2010, p. 34)? As a white woman does Jaffe (2017) have the right to push back on the work of people of color as not going far enough in serving social justice? Do all people have a stake in an issue such as affirmative action? Should Jaffe (2017) be singling out one episode of a show to “burst” the bubble of its appeal? Is that fair? Does fair matter?

With such pointed questions left unanswered, the fact that they came up in the first place meant that the work of a discerning listener was unfinished. A look outside of Jaffe’s (2017) podcast was in order. After all, is it fair as a listener to only focus on one view of one episode of one show? In research done by Barreiro (2010) on what audiences, particularly Latino audiences, look for in Ugly Betty, she offers this take on the Ugly Betty:

Although Ugly Betty’s text and its official Website seem to make efforts to include race

discourses, the audience’s perception seems to be far from focusing on racial or cultural matters as the series’ main point. Instead, viewers concentrate more on the entertainment nature of the text. Ugly Betty seems to unify culturally mixed audiences by acting as the connector between Hispanic and Anglo viewers. The series presents universal themes that allow multicultural audiences to relate to them, while acknowledging, but not concentrating on, the multicultural element of the text. While cast as an outsider, Betty becomes an intrinsic component of the society that surrounds her, providing an empowering Latino representation (Barreiro 2010, p. 39).