Text

I had my first spontaneous encounter of quarantine recently. It was a humid Sunday late afternoon, storm clouds had dispersed but their moisture clung to the air. I was walking my bike down a winding road, moving slowly so as to better observe my new surroundings, mostly mid-rise apartment buildings and villas by the eastern shore of the Hudson.

I heard voices behind me, coming from two people, and I diverted my steps to a little paved half-island with a bench, wanting them to overtake me so I would have more privacy. But the voices followed, so I looked behind and was stunned to see a familiar form, face, next to an older silver-haired woman, who I gathered to be her mom. We knew each other from college and before that, a program that we did the summer before our senior HS year. But we had largely lost contact over the past few years, except for the occasional Twitter interaction.

I froze, incredulous that our bodies were both here, at the same time and place, and waited for her eyes to catch mine, wondering if they would. She turned around and froze, too. Is that you? she exclaimed. I took off my helmet, and we exchanged salutations in excited tones too loud for the quiet street.

We had both been hibernating in our family’s house, so we were startled by each other, attempting to compose ourselves, our minds rapidly trying to remember the protocols for exchanging pleasantries with an old but distant friend. What do I say? How much do I probe? How short or long should my answers be? How do we end the conversation and part ways? It was stressful to think about what words I should say while saying them.

The exchange lasted likely no more than five minutes, but it felt much longer. When when she and her mom waived good bye and headed off, I still felt a bit stunned, my mind turning over the couple sentences that we exchanged. She had a job now, a boyfriend who worked across the country, lived with her mom, wore V-neck fluttery long-sleeves. I had learned so much and knew so little.

I waited until her and her mom disappeared down the road and then hopped back onto my bike and rode away.

0 notes

Text

my friend told me last summer that she was reading a book about travel and it said that the first rule of travel is: do not go back the way you came.

I think about that a lot.

0 notes

Text

“Matins” by Louise Glück

You want to know how I spend my time? I walk the front lawn, pretending to be weeding. You ought to know I’m never weeding, on my knees, pulling clumps of clover from the flower beds: in fact I’m looking for courage, for some evidence my life will change, though it takes forever, checking each clump for the symbolic leaf, and soon the summer is ending, already the leaves turning, always the sick trees going first, the dying turning brilliant yellow, while a few dark birds perform their curfew of music. You want to see my hands? As empty now as at the first note. Or was the point always to continue without a sign?

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

“By failing he created loss, and loss was the threshold to freedom: an awkward and uncomfortable threshold, but the only one he had ever been able to cross...” (Rachel Cusk, Transit, 24)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

reflections on bike protest, 7/24

THIS IS WHAT COMMUNITY LOOKS LIKE

THIS IS WHAT COMMUNITY LOOKS LIKE

THIS IS WHAT COMMUNITY LOOKS LIKE

I was in a swarm of bikers chanting these words out loud last Friday. I could barely summon the vocal cords to utter them out loud though. Will I ever take part in this protest chant and not feel like a fraud? I am not sure what a community is or looks like, or if I have belonged to one that was not actually a family, a clique, a friend group, or a loose assemblage of some kind.

I had arrived already sweaty at Grand Army Plaza a few minutes after six o’clock and immediately spotted the amassing of bikers. This was my first time participating in a bike protest, or any of the protests for the renewed Black Lives Matter movement. Cloistered in my parents’ house for the past four months, I had been unable to go beyond a walking radius from my house, which meant, no protests. But the past week, I was staying with my sister in Brooklyn, which entailed a newfound freedom of movement.

I didn’t know who would show up, where we would ride, how we would coordinate the over a hundred bikers who would eventually arrive. I glanced over to my right and spotted a pale young man clad in all-black, waiting with his bike. We held brief eye contact and then broke away, nervous.

A long-limbed dark-skinned man, presumably one of the leaders, began speaking. He welcomed us and asked any first-time riders to raise their hands. I tentatively raised mine, relieved to see many other elevated arms. He informed us that we would actually ride out at 6:30, half an hour after the published start time, to wait for folks to gather. In the meantime, don’t be afraid to converse to the person to your right or left, he said.

My stomach sank. Oh no, socializing. This was like on the first day of school when you sit down in a boisterous classroom and silently wait for the teacher to arrive so that your silence could finally be justified. I glanced around, checking out the crowd while avoiding any lingering eye contact.

My gaze registered the multitude of arms—tanned, dark, pale, tatted, muscled, freckled. Sleeveless tops – form-fitting crop-tops, muscle tees. Bike shorts, cropped work pants, yoga leggings. Skins and surfaces and fittings. Clearly some bikers were returning—their bikes sported weathered cardboard signs proclaiming Black lives matter in Sharpie and glitter.

I had 25 minutes to kill before riding. To my immense relief, I had forgotten my helmet back at my sister’s apartment, so I left the mass of bikers to retrieve it. By the time I returned, the crowd of bikers had more than doubled – over a hundred were present. We started riding half past six, beginning our chanting that would continue for another three hours. We moved at a steady pace, our chains smoothly whirring along accompanied by our near-constant chanting. We rode through Crown Heights, Brownsville, Canarsie, Flatlands, turned back north, through Flatbush, and then back through Prospect Park, returning where we began, Grand Army Plaza. The ride lasted a total of three hours.

A smaller group of bikers, most of them in highlighter traffic vests, rode on the sidelines of the protest, shepherding us to stay within the two lanes. At each intersection, they stood off and guarded each side of the lane to block off any stray incoming cars. They rode alongside us, leading chants and occasionally yelling for bikers to stay on the right within our two-lane width.

The bikers at the front began yelling HOLD, this word reverberating down the swarm, moving like a wave through water. They raised their right arms at a 90 degree angle and began slowing down. Perplexed and surprised, I imitated them, slowing down and raising my arm at clumsy 90. We all stopped at an intersection. I tucked away HOLD and the 90 degree arm within my cache of knowledge and kept moving.

The next time, I heard shouts of RIGHT RIGHT RIGHT and saw arms extending in the same direction, signaling a turn. HOLE rang out, and I saw hands reach out, fingers pointed down to the ground, and sure enough, I saw a pothole. The next few times, I yelled out HOLE, too, whenever I saw uneven ground ahead. Sometimes it is worth just hearing the sound of your voice.

A young man swerved his bike and lay it perpendicular to the incoming bikers, a stick in the ground forcing others to flow around him. My initial frustration dissolved once I realized that he was covering a huge pothole that would’ve flattened several tires had they run over it. My heart thudded with appreciation.

I joined the protest knowing nothing—not knowing the route, or how many people would show up, how long we would ride for. Despite this, I was able to move in sync with everyone else by reading, listening, following the directives being called out. I moved as if I knew what was happening, although I didn’t. All I needed, though, was to trust that others did. Moving as a pack, compact and in sync, required a constant sense of trust and coordination.

There was something there, even if it didn’t feel like community. The ride itself, the demands of the movement, required constant full-body alertness, coordination, and organization between us that birthed a sense of affinity. By the time we returned to Grand Army Plaza at 9:30 pm, I no longer felt like an alien body amidst other alien bodies, but one part of a panting, sweating, exhilarated group that had driven their bodies to exhaustion and shouted to hoarseness about Black lives mattering.

What is community? Perhaps the first mistake is thinking of community as a noun, as a stable thing that exists, instead of a constant doing that generates and enforces its own formation as it moves along. We remained strangers after I rode away from the mass of bikers, but I now knew a code of conduct that could govern our collective movements, which feels like an important place to start.

0 notes

Text

I want to live in a house

that fills up, spills over, overheats. Where the table is heavy, laden with food, stained, crumbs all over. Glass cups with clear honeyed liquid and mugs with milky residue puddled at the bottom. A meowing cat interloping in the leftovers. A heaviness laying over the table, an accumulation of knit-picked arguments left unraveled. Where the talking animals go off to the room over, huddling together as they stare and occasionally yelp at a 13-inch screen for hours.

I want to live in a house where the hands return, their midnight bustle sweeping away the stale heaviness. One to the sink, which fills up with soapy bubbles; one to the table, its crusted veneer slowly disintegrating; and another to the floor, hands intermingled with feet as they pick up the remains of the day.

I want to live in a house run by a continuous exchange of gifts. The gift of waking up to a clean sink, kneaded dough on its way to the oven, the latest bounty from the garden.

I want to live in a house that is made and unmade and made again every day.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“People have to want something to exist”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Walking down this sticky road neath the gentle roar of swaying trees really takes me back to southeast Asia.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went to the river to find more space to be and to think but I mostly found these ducks.

0 notes

Text

Finding a new trail

Leaving my front door, I turned left, walking south. After a few intersections, I hit Mosholu Avenue, a commercial street whose name derives from the Algonquin word for “smooth stones” or “small stones.” Oddly, the river that does run through Riverdale, which likely created the “smooth stones” which the word mosholu describes, is named Tibbetts Creek, after a European settler. It’s kind of odd to name a commercial avenue after a geographic feature of a river, no? But perhaps that could be read in a hopeful manner—to think of the urban commercial avenue as a river incarnate, a life-giving force through the town.

At Mosholu, I turned right (west, toward the river), following the avenue as it rounded corner, passing the local Tudor-style NYPL branch. Past the Riverdale Neighborhood House, a quaint colonial building with a pool and playground that looks vaguely hospitable for a certain kind of respectable citizen. Past the weedy baseball field, past the playground, mostly empty during the pandemic, but sometimes with a gaggle of teenage guys, chilling.

I usually crossed the street at this point and walked up a sidewalk to a curious little park that exists as an island amidst a crisscrossing web of highways. I walked up the street mostly because I didn’t feel like crossing the six-lane avenue just yet. Wanted secluded lanes that would allow me to keep to myself.

The park consists of a hilltop, a green island that just peeps over a loop-de-loop of highways, another one of Robert Moses’ concrete graffiti scrawls over the landscape of the Bronx. There’s a dog park in the middle that’s sort of falling apart; I’ve never seen anyone using it, dog or human. Mostly there are a lot of benches, facing outward and inward.

I kept walking, down garden-style, five-story, red brick apartments. Turned onto a quiet residential road with suburban single-family houses. No sidewalks, just gravelly weedy transitional spaces between grass and pavement.

I remember the gates first. I didn’t yet know it was a school; all I saw was a gate and behind it, trimmed lawns rolling up to a genteel brick building. A gated compound, vast flat fields, lacrosse fields, parking lots – of course, a private school. I followed the road as it sloped downward, hugging the edge of the prep school. There is something so sinister about a totally manicured lawn. How much labor, how much capital, do you need, to sustain this ugly face of control? Walking alongside the compound, I thought of all the iterations of this sort of gated, fenced-in, land – estates, kingdoms, plantations.

At the end of the hill, the road spilled into nondescript dirt space. From a handful of cars, I gathered that it was a parking lot. The air changed, becoming cooler, denser. Ahead, the gravel met a chain-link fence tagged with the NYC Parks logo, a green maple leaf. This was a park? An old traffic cone and squashed cardboard boxes lay fallen against the fence. If you were walking quickly, or even driving, you would miss it entirely. My mind flashed to other Hudson parks I knew – Riverside Park, Riverbank State Park, Fort Tryon, Inwood. But this one was new, never previously encountered on a map or in person.

It seemed out of nowhere, a glen of hickory and oak, between mansions and railroads. No surprise, my mind flashed back to the gated private school that I had just passed. It was not lost on me that the serendipity of slipping into this trail occurred next to a private school with a 50K tuition in one of the richest neighborhoods in this zip code. Technically, this is a public park, but it is geographically located for the wealthy elite.

Not knowing what was inside this park, or how far it extended, I entered. Dusty paths, tall hickory and oak, flush with undergrowth. I followed a dirt trail and saw the glimmers of sunlight through the kaleidoscopic canopy of trees. I soon found the chain-link fence that formed the eastern perimeter of this park, and glimpsed the water beyond, drinking in its murmuring waves. Wandering more, I came across a dried-up gully, with a fallen tree trunk spanning its width. The top of the trunk had eroded into a temptingly flat surface. Certainly passable, if one had the guts to try. I walked five steps forward, paused, and retreated. Too old.

One thing to know is that the trees there were very tall. They do not rival the California redwoods, but the distance between the bushy undergrowth and the swaying canopy overhead felt vast. The treetops were so tall that they caught all the river wind, swirling it amongst their branches, so that I, a small ant standing below, heard the roar of the wind more so than felt its touch on my skin.

In the immediate vicinity of my body, there was the peace and quiet of overgrown trails and mossy trunks, but several leagues upward (what does a league measure? I do not know, but it feels like the right word), the treetops were in a great upheaval—maple, oak, hickory, all mingling—caught up in the wind, swaying and fluttering in one uplift.

The trail itself is fairly narrow, walk about 15 meters one way and you will see the faint outlines of a chain-link fences. On the riverside, you’ll catch sight of the railroads ahead, and on the roadside, the outlines of secluded houses, lights of vehicles driving by.

But this place, it felt like a little gem, one that, momentarily, was all my own. I knew that if I pulled up Google Maps, I would find this trail on the maps, and that if I searched it online, I would find the NYC Parks page for this trail, explaining in byte-form. The zoning, the planning committee, the pushback, et cetera. But it would say nothing about how it felt, walking through desolate suburban streets and posh gated lawns to then discover, without notice, relief. A windy green corridor, tucked by the river, rushing, still, roaring, quiet—all at once.

I returned to the trail the next day, and the day after that. I found my legs craving, turning toward the park. One day during dinner, my mom inquired after where I went walking that day, and I mentioned that I went to Riverdale Park, by the river. They were puzzled – where?

Is it by the train station, my mom asked. By the train station, I sometimes see a little trail there and wonder what it is, she said, referring to the Riverdale Metro North station that services the Hudson Line, connecting Grand Central in midtown to Poughkeepsie up north in the valley.

No, I shake my head, no, thinking that she was referring to the pathetic concrete strip accessible to pedestrians by the train station. It’s basically a 15 meter long sidewalk with a single bench and overflowing trash cans where you might sit down and look over the Hudson. It’s certainly something, at least, but one cannot feel antsy, gazing upon the vast sweep of the Hudson while hemmed in by these arbitrary fences for “viewing.”

Mine was a place that I had resisted placing on a map; it was this little gem of a shady glen pocketed into the outskirts of a suburb. It’s further south of here, next to Wave Hill, I said. You walked there? My dad asked, incredulous. Yes, I walked, I said, hiding my pride in my nonchalance. It’s only like twenty minutes.

Of course, my parents did not understand. They keep to their established routes – to the train station, to the field, to the grocery store. Whatever trail that my mom was referring to was not it. Besides, the trail was quite far from the train station – at least half a mile or so south of it.

I showed them the trail on Google Maps, pointing out the green rectangular patch. Ah, we have never been there, they mused. A week or so later, Saturday afternoon, instead of taking the car to the beach on Long Island, as is our tradition, we drove over to the trail. They were astonished when they arrived at the dirt entrance of the park. A secret! They exclaimed. They’ve been keeping this a secret! Five years and we had no idea this place existed. Who would have known? So out of the way. Who was keeping this secret??

I chuckled at their astonishment, their indignation, that they had only now discovered this place. Part of my reaction is a weariness of knowing my parents calcified habits. They have lived in New York City for almost a decade now but still – my dad especially – are still suburban in their bones. Their favorite store remains Costco, where they shop at least once a week, despite having been empty nesters for more than a few years now. During the weekends, they drive up north to the suburbs to go hiking more often than they drive south to Manhattan for entertainment. The most urban that they venture is to the local Asian neighborhoods – Chinatown, Flushing, Elmhurst, for shopping and eating.

But their indignant exclamation, they’ve been keeping this secret! lingers with me and evinces, I think, a kernel of truth. If you zoom out from where I’m standing, in this little park in Riverdale, and run your eyes down the western length of New York City, you will see green hugging most of the coastline, corresponding to the richest zip codes in Manhattan. I think about the other, far larger and more famous park, Van Cortlandt Park, that sits next to the 242nd street subway station and attracts more populous crowds of Black, Latinx, Asian, and white residents, picnicking, playing baseball, soccer, flying kites, working out. Of course, Van Cortlandt has far more acreage and resources to avail itself to such recreation, but the park is well-trodden and busy, evidenced not only by the multitude of bodies but also the glass shards that depressingly litter its trails. Most of all, I guess, Van Cortlandt is unmissable, obvious, in plain sight.

On the other hand, the trail running through Riverdale Park is sequestered away, on the margins with a nondescript entrance and overgrown signage. This trail offers the illusory feeling of having discovered it by yourself, a feeling of privacy within a public space. And within this privacy, unexpected and lively things emerge. But how might relishing the serendipitous joys of stumbling into one’s own world of green manifest not the sublimity of nature (or the self, touched by nature), but rather the hoarding of wealth, in its material and immaterial forms, across private and public lines? How might we deem both of these to be true and think of them together? Things to keep thinking about…

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

6/9/20: funny thing about apt complexes in NY is how they are often these plain bricked rectangular prisms but named as if they were the estates of the English gentry.

0 notes

Text

6/9/20: do you see that dusky blue shadow peeping behind the buildings and the trees? That’s New Jersey—the Palisades, specifically. It’s perceptible from here because the land goes downhill from this point on the road (Riverdale Avenue) until you hit the Hudson. You can see how the land descends if you track the cars. I love how steep and rocky New York gets the further north you go.

0 notes

Text

6/9/20: it’s comforting to see the corner delis still open in the middle of all the emptiness

0 notes

Text

6/9/20, evening. Summer arrived all at once and the only relief comes after seven now.

0 notes

Text

reflections on compulsory heterosexuality and “The Half of It”

*spoiler alert*

In an interview with Netflix, Alice Wu beautifully sums up the queer, coming-of-age film, The Half of It:

“This story is really about three people who collide and, in that moment in time, each of them ends up finding the piece within themselves that allows them to become the person that they need to be.”

Thus, the movie sets up and subverts expectations of what a love story should be. The emotional force of the movie stems from the unconventional bond between sharp-minded and pragmatic nerd, Ellie Chu, and golden-retriever-in-human-form, Paul Munsky. They are complementary opposites: Munsky cares for and stands up for Ellie with his brazen good-naturedness, giving her the confidence to seize the future for herself, and Ellie offers her words as a way to help him realize his dreams and carve out independence from his chaotic family. They are platonic soulmates.

Nonetheless, there is a moment in the film where the ball drops on their lovely and unexpected friendship. It’s after a football game, after Paul has scored the school’s sole touchdown in years. He enters a room, leaning against the doorway in a classic he’s-about-to-kiss-you stance. As Ellie awkwardly holds an armful of Yakult, he says, “Hey,” prompting her to look up. He stares for a split second too long before swooping in for an (awful, terrible, wretched) kiss.

His lips barely graze Ellie’s before she freaks out and moves away, dropping the prized Yakult on the floor in the process. “What are you doing,” Ellie asks Paul accusingly. Indeed, when I was watching the film, I was screaming at Paul: WHAT ARE YOU DOING???

I was mad at Paul, and still at the end of the movie, I remained befuddled by the kiss scene. It came out of nowhere, I said incredulously, to my siblings, with whom I watched it for the first time. (I subsequently had two more The Half Of It watch parties...listen, we are all trying to survive this quarantine.)

Sarah, my sister mentioned that she had discussed with her queer friends how close relationships between a guy and a girl so easily, almost inevitably, are scripted as romantic love. The strong-willed tomboyish girl strikes up a relationship with the puppy-dog, supportive boy and they get along swell until the boy develops feelings for her and she, while initially resistant, ultimately (naturally) admits her feelings for him, and they end up happily together.

How many stories did you read growing up that followed this plot line? Me? So many, too many. I’m reminded of the term “compulsory heterosexuality” coined by feminist theorist and poet Adrienne Rich in her 1980 essay wherein she argues against the notion that all women are naturally predisposed to be sexually attracted to men (and the following supposition that lesbianism is unnatural). While sapphic relations are much more visible and accepted in the mainstream today (hello, Portrait of a Lady on Fire), compulsory heterosexuality profoundly endures in the ways that relationships between girls and boys are charged with romanticism even before they can be fully understood by either party.

I’m reminded of my first real best friend in high school, who was a gay guy whom I met in a summer program and who remains my good friend. Despite him living in Texas and me in New York, we digitally sutured ourselves to each other during our senior year of high school. We were both fairly miserable, anxious and depressed, overwhelmed by college applications and desperately wanting to get out, by any means necessary. We became what in-the-know people would now refer to as “codependent,” and after a few months of constant texting I realized that this urge I felt to constantly be in contact with him, like a ghostly limb, must be a crush, a necessarily doomed desire. I guarded this feeling for months and, in short, after convoluted and messy communications, I confessed my feelings, he responded graciously, and we gave ourselves some distance.

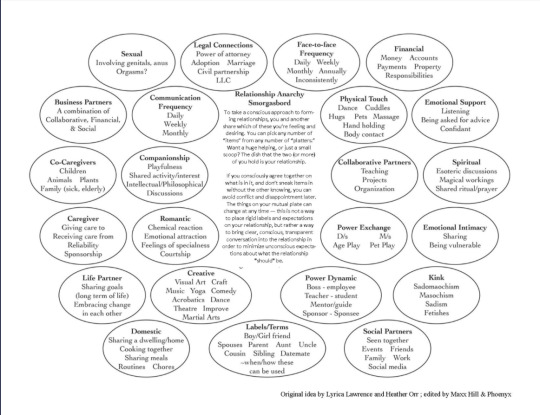

While my feelings were undoubtedly complicated, I realized that I could have saved myself a lot of drama if I had interrogated my feelings and allowed them to exist outside of the mandate of heterosexuality. This desire to merge, to be united with someone, is a feeling that I’ve had in my closest relationships, many of them no less important for being mostly platonic. But highschool me immediately labeled my feelings as “romantic,” relegating them to a distinct and privileged category. My friend texted me this “relationship anarchy smorgasbord” chart a few months ago that I think better illustrates the kinds of intimacies that we share with each other:

Source: Phoenyx Enterprising

(https://www.phoenyxenterprising.com/relating.html)

Relationship anarchy, from my very cursory knowledge, is predicated upon open mutual acknowledgment and agreement of the forms of intimacy that bind people together. This kind of communication is extremely queer, in my opinion, and necessarily antithetical to compulsory heterosexuality, which is sustained through implicit projection.

Reflecting on my personal experiences, I’ve come to understand and sympathize with Paul, to some degree. I still am deeply unimpressed by his instinct to ACT on his feelings without first asking Ellie how she felt, or whether she reciprocated his feelings. However, he and Ellie bond intensely over a short period of time; he finds something like a soulmate but lacks any interpretative framework for the intense feelings he has for a girl outside of heterosexual romantic love, so he immediately calls it a crush and, with his white man confidence, misreads Ellie’s affection for attraction. My other friend, Joce, brilliantly highlighted the football game that precedes the failed kiss scene. When Paul looks up at the stands, he glances at his girlfriend, Aster, but his gaze settles upon Ellie. In realizing that perhaps he was actually looking for Ellie the whole time, he realizes that Ellie, instead of Aster, is his love interest.

The thing is, they are each other’s love interest, but not in a way that can be easily defined. I’m not saying that it’s impossible for Paul to have had romantic feelings for Ellie, but that the movie acknowledges and reveals the absurd fallacy of a straightforward heterosexual reading of their relationship and in doing so demonstrates the poverty of our frameworks and vocabulary for interpreting matters of the heart. The Half of It is very much a feel-good coming-of-age movie, but it is radical in the ways that it refuses the form of a romantic love story—either heterosexual or lesbian—and instead focuses on the unexpected and opaque ways that we stumble into love.

0 notes

Text

I spotted this site on my walk two days ago (6/1) and I can’t tell if it was abandoned in the process of construction or in the process of destruction. It’s been sitting here like this, without much change, for awhile.

0 notes