Text

Def Jam's How to Be a Player is a 1997 American sex comedy film, starring Bill Bellamy, Natalie Desselle and Bernie Mac. The film was directed by Lionel C. Martin, and written by Mark Brown and Demetria Johnson.

The How to Be a Player Soundtrack, released by Def Jam Recordings on August 5, 1997, featured the hit single "Big Bad Mamma" by Foxy Brown featuring Dru Hill.

Def Jam's How to Be a Player is a 1997 American sex comedy film, starring Bill Bellamy, Natalie Desselle and Bernie Mac. The film was directed by Lionel C. Martin, and written by Mark Brown and Demetria Johnson.

The How to Be a Player Soundtrack, released by Def Jam Recordings on August 5, 1997, featured the hit single "Big Bad Mamma" by Foxy Brown featuring Dru Hill.

Bill Bellamy — Drayton "Dray" Jackson

Natalie Desselle — Jennifer "Jenny" Jackson

Lark Voorhies — Lisa

Mari Morrow — Katrina

Pierre Edwards — David

Bernie Mac — Buster

BeBe Drake - Mama Jackson

Jermaine 'Huggy' Hopkins — Kilo

dailymotion

Anthony Johnson — Spootie

Max Julien — Uncle Fred

Beverly Johnson — Robin

Gilbert Gottfried — Tony the Doorman

Crawford was born in DeKalb, Illinois, on February 20, 1966,[2] the daughter of Dan Crawford and Jennifer Sue Crawford-Moluf (née Walker).[3] She has two sisters, Chris and Danielle,[4] and a brother, Jeffery, who died of childhood leukemia at age 3.[5] On social media, she has stated that her family had been in the United States for generations and that her ancestry was mostly German, English, and French.[6] She is Christian.[7] Appearing in an episode of Who Do You Think You Are? in 2013, she discovered that her ancestors included European nobility and that she was descended from Charlemagne.

Stacii Jae Johnson — Sherri

Elise Neal — Nadine

Black Panther: World of Wakanda is a comic book series and a spin-off from the Marvel Comics Black Panther title.[1][2] It published six issues before being canceled. The series was primarily written by Roxane Gay, with poet Yona Harvey contributing a story to the first issue.[3] Alitha E. Martinez drew the majority of the art for the series, for which Afua Richardson contributed cover art to the first five issues, as well as art for a short story in the first issue. Gay and Harvey became the first two black women to author a series for Marvel;[3] counting Martinez and Richardson, upon its debut the series itself was helmed entirely by black women.[4] Ta-Nehisi Coates served as a consultant for the series.

Black Panther: World of Wakanda won a 2018 Eisner Award for Best Limited Series.[5] The series also won a 2018 GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Comic Book.

After the success of the Black Panther series relaunch in April 2016, written by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Marvel developed a companion piece set in the fictional African country of Wakanda, home to the Black Panther. Coates recommended Gay and Harvey to pen the series. He had seen Gay read a short story about zombies two years earlier that he recalled as "the most surprising, unexpected, coolest zombie story you ever want to see"; Harvey had been his classmate at Howard University and he felt her skills as a poet would lend themselves to the comic-book form, telling The New York Times, "That’s just so little space, and you have to speak with so much power. I thought she’d be a natural."[7]

The series debuted November 9, 2016 (with a cover date of January 2017). Harvey wrote a 10-page origin story for Wakanda's revolutionary leader Zenzi, and has said she drew on the example of Winnie Mandela as inspiration.[8] Gay has mentioned the character of Olivia Pope in the first season of Scandal and the original USA version of La Femme Nikita as influences for the series.[9]

The series was canceled after six issues due to poor sales.[4]

The first World of Wakanda story arc (issues #1-5) features Ayo and Aneka, two Wakandan members of the Dora Milaje, the Black Panther's female security force. Ayo and Aneka are also lovers. The first storyline also describes Zenzi, a revolutionary and villain in the Black Panther series.[10]

The first issue is a prequel to Coates's Black Panther series, describing the backstory of women in Wakanda. Captain Aneka of the Dora Milaje must deal with an impertinent new recruit who simultaneously challenges her and fascinates her. Meanwhile, Zenzi discovers that she has enhanced abilities and has to decide the best way to use them. Contrasting World of Wakanda with its Black Panther predecessor, Caitlin Rosberg writes at The A.V. Club that "World Of Wakanda feels more intimate, and all the more powerful for it. It’s deeply invested in the identities of black women both as characters and more importantly as creators, making it clear that these aren’t just background characters in T’Challa’s [Black Panther's] life."[11] Writing for Inverse magazine, Caitlin Busch called the first installment "a tear-jerking love story for the ages, encapsulating all the emotion, romance, tragedy, and fearsome intelligence of Black Panther’s Wakandan civilization."[12]

As the story moves along, Aneka and Ayo grow closer, but concerns over the righteousness of T'Challa's priorities lead them to leave the sisterhood. Aneka is conflicted about making her relationship with Ayo more public, but she agrees to take a vacation trip together. Folami tries to cause trouble for the Dora Milaje, but Queen Ramonda rebuffs her attempt and alerts Zola. Aneka and Ayo cut their trip short when they are summoned back to Wakanda. They become estranged when they return from their vacation to find that Shuri has been killed. Aneka takes on a solo mission to rescue women from an evil chieftain, and she is forced to kill him. She is arrested, and Folami, the chieftain's daughter, vows revenge. The women of Wakanda rise up to object to Aneka's imprisonment, and the Dora Milaje take a more active role in peacekeeping. Folami threatens Ayo and eventually kills Mistress Zola. Ayo breaks Aneka out of prison and the two vow to remain together and to fight injustice as the masked Midnight Angels.

The series' final issue, #6, is a standalone story by Rembert Browne and Joe Bennett about Kasper Cole and White Tiger.

J. Anthony Brown — Uncle Snook

Amber Smith — Amber

Jerod Mixon — Kid #1

Jamal Mixon — Kid #2

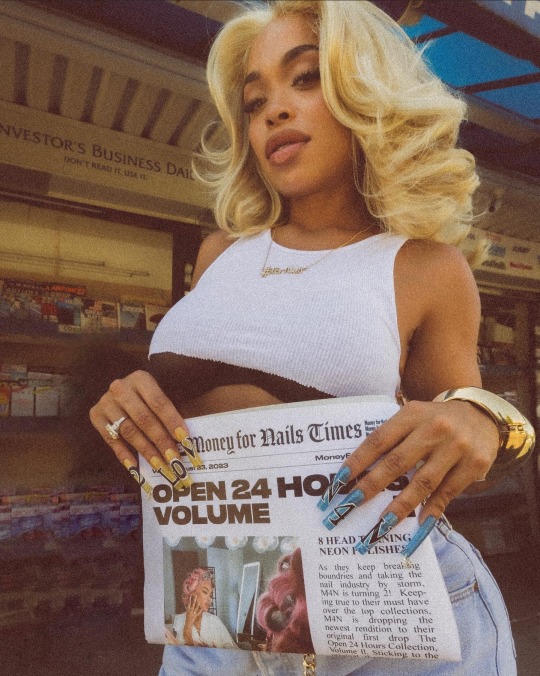

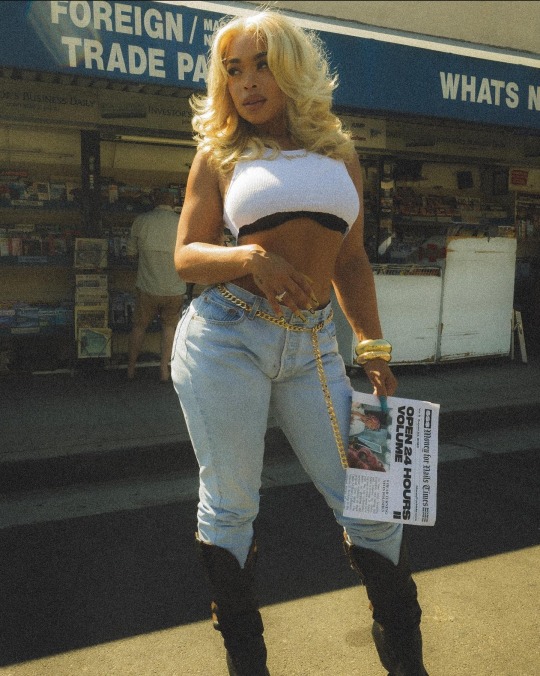

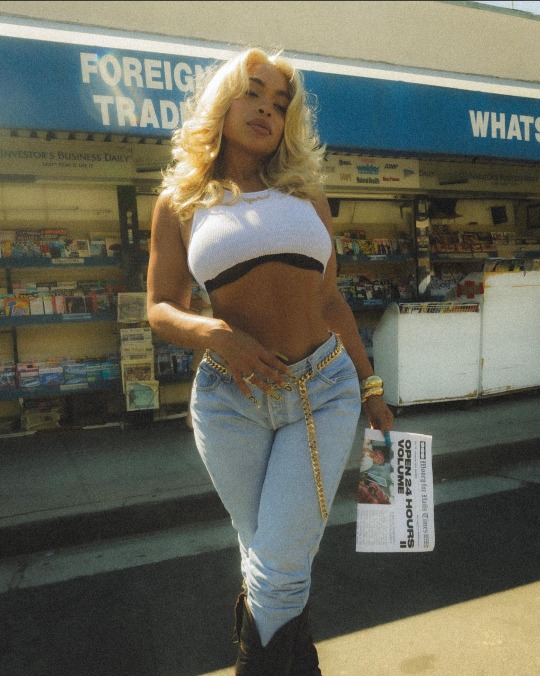

IG: heathersanders_

353 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ann Carroll Smith (née Fitzhugh; 1805–1875)[1] was an American abolitionist, mother of Elizabeth Smith Miller, and the spouse of Gerrit Smith. Her older brother was Henry Fitzhugh.

Ann and Gerrit Smith's Peterboro, New York, home was a station on the Underground Railroad. Known as "Nancy,"[2] Ann Fitzhugh Smith frequently traveled via an enclosed carriage to permit her carriage to be used, in her absence, to convey veiled fugitives on their way to Canada.[3]

In 1822, Fitzhugh – living in Rochester, New York, and formerly of Hagerstown, Maryland – married Gerrit Smith. She was devout and was influential in her husband's religious conversion and beliefs about social reform and slavery.[citation needed]

Abolitionist[edit]

The Smith household hosted both abolitionist and early suffrage meetings in the pre-Civil War period. As a child in Chewsville, near Hagerstown, Maryland, she was given a slave, Harriet Sims, who was sold and was further enslaved in Kentucky, with her spouse Samuel Russell. Ann and Gerrit located the Russells, purchased their freedom in 1841, and aided them in settling at Peterboro.[4]

The Smith couple had joined the abolition movement fully in October 1835, after a meeting of the New York State Anti-Slavery Society in Utica, New York, was forcibly broken up by local pro-slavery sympathizers. The couple interceded from the audience, and offered the Peterboro mansion as a safe haven to reconvene the gathering.[5] Therewas no other offer. As the crowd that showed up was too large for Smith's house, the meeting was moved to the largest building in Peterboro, the Presbyterian Church.[citation needed]

While Ann's daughter Elizabeth attended a Quaker school in Philadelphia, Ann stayed in the city for extended periods during 1836-37 and 1839. These stays brought Ann into the circle of Lucretia and James Mott, abolitionists C.C. Burleigh and Mary Grew. Ann and her daughter taught Sunday school in one of Philadelphia's African-American communities.

Stockjobbers were institutions that acted as market makers in the London Stock Exchange. The business of stockjobbing emerged in the 1690s during England's Financial Revolution. During the 18th century the jobbers attracted numerous critiques from Thomas Mortimer, Daniel Defoe and others. These writers denounced the use of market manipulation and front running and regarded it as unethical that the jobbers made money without any interest in the stocks involved. The business survived repeated legislation to ban it and became institutionalised.

Prior to the "Big Bang" deregulation of 1986, every stock traded on the Exchange passed through a 'jobber's book', that is, they acted as the ultimate purchasers of shares sold and the source of shares purchased, by stockbrokers on behalf of the latters' clients. Stockbrokers in turn were not permitted to be market makers.[1]

In the final years of stockjobbing, the leading firms were Akroyd & Smithers, Wedd Durlacher, Pinchin Denny, Smith Brothers, Bisgood Bishop and Charles Pulley.[2] All of these firms were acquired by investment banks and other financial institutions.

Henry Fitzhugh (August 7, 1801 "The Hive", Washington County, Maryland – August 11, 1866) was an American merchant, businessman and politician from New York.

Life[edit]

He was the son of Col. William Fitzhugh, Jr. (1761–1839, one of the founders of Rochester, New York) and Ann (Hughes) Fitzhugh (1771–1829). Baptised and raised in Saint John's Parish, Henry removed with the Fitzhugh family at the age of 15 to a tract of the Phelps and Gorham Purchase in 1816. On December 11, 1827, Henry married Elizabeth Barbara Carroll (1806–1866, sister of Charles H. Carroll) at Groveland, New York.

He was a member of the New York State Assembly (Oswego Co.) in 1849. He was a Canal Commissioner from 1852 to 1857, elected on the Whig ticket in the New York state election, 1851 and New York state election, 1854.

He was buried at the Williamsburg Cemetery in Groveland, NY.

U.S. presidential candidates James G. Birney and Gerrit Smith, and State Senator Frederick F. Backus (1794–1858), were his brothers-in-law.

0 notes

Text

Blue Lion

ArcaOS was formally announced on October 23, 2015, at the Warpstock 2015 event (an OS/2 user group event) under the code name "Blue Lion" by Arca Noae's Managing Member, Lewis Rosenthal.[4][5]

Some of the planned features for Blue Lion announced at the time were:[4]

new Symmetric multiprocessing kernel

new pre-boot menu

new OS installer with support for installation from USB flash drive and across a network

device drivers already produced by Arca Noae as part of their Drivers & Software Subscription[50]

the latest Workplace Shell enhancements

updated CUPS print subsystem

updated PostScript printer driver pack

localization in several languages besides English[51]

At the time of the announcement, the initial release was projected for late third quarter of 2016, but Arca Noae also stated that no actual release date had been set.

ArcaOS 5.0

The name "ArcaOS" was first published in a TechRepublic article[52] on May 26, 2016, while the arcaos.com domain was registered December 20, 2015. In the same TechRepublic article, Lewis Rosenthal was quoted as saying that the first release of ArcaOS would be version 5.0, as it follows onto the last release of OS/2 Warp from IBM, which was 4.52 (also known as Merlin Convenience Pack 2, or MCP2).[53]

ArcaOS 5.0 was released May 15, 2017.[1] There were two editions released: a commercial edition, intended for enterprise use (including 12 months of upgraded/prioritized technical support), and a personal edition, targeted at non-business users (including six months of standard technical support) at a reduced price.[54] Pricing was listed as $229 per license for the commercial edition, and $129 per license for the personal edition, with $99 promotional price in effect for the first 90 days following release.

ArcaOS 5.0 was followed by a number of maintenance releases between 2017 and 2021. In addition to bug fixes and driver updates, the maintenance releases added some significant features such as USB 3.0 support, the ability to install from a USB drive, and the update facility.[28] During Warpstock 2021, Arca Noae announced that 5.0.7 would be the final maintenance release of 5.0, and that it would be followed by the 5.1 release.[55]

Stockjobbers were institutions that acted as market makers in the London Stock Exchange. The business of stockjobbing emerged in the 1690s during England's Financial Revolution. During the 18th century the jobbers attracted numerous critiques from Thomas Mortimer, Daniel Defoe and others. These writers denounced the use of market manipulation and front running and regarded it as unethical that the jobbers made money without any interest in the stocks involved. The business survived repeated legislation to ban it and became institutionalised.

Prior to the "Big Bang" deregulation of 1986, every stock traded on the Exchange passed through a 'jobber's book', that is, they acted as the ultimate purchasers of shares sold and the source of shares purchased, by stockbrokers on behalf of the latters' clients. Stockbrokers in turn were not permitted to be market makers.[1]

In the final years of stockjobbing, the leading firms were Akroyd & Smithers, Wedd Durlacher, Pinchin Denny, Smith Brothers, Bisgood Bishop and Charles Pulley.[2] All of these firms were acquired by investment banks and other financial institutions.

Mary Edmonia Lewis, also known as "Wildfire" (c. July 4, 1844 – September 17, 1907), was an American sculptor, of mixed African-American and Native American (Mississauga Ojibwe) heritage. Born free in Upstate New York, she worked for most of her career in Rome, Italy. She was the first African-American and Native American sculptor to achieve national and then international prominence.[1] She began to gain prominence in the United States during the Civil War; at the end of the 19th century, she remained the only Black woman artist who had participated in and been recognized to any extent by the American artistic mainstream.[2] In 2002, the scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Edmonia Lewis on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[3]

Her work is known for incorporating themes relating to Black people and indigenous peoples of the Americas into Neoclassical-style sculpture.

According to the American National Biography, reliable information about her early life is limited, and Lewis "was often inconsistent in interviews even with basic facts about her origins, preferring to present herself as the exotic product of a childhood spent roaming the forests with her mother’s people."[4] On official documents she variously gave 1842, 1844, and 1854 as her birth year.[5] She was born near Albany, New York.[4] Most of her girlhood was apparently spent in Newark, New Jersey.[6][7]

Her mother, Catherine Mike Lewis, was African-Native American, of Mississauga Ojibwe and African-American descent.[8][9] She was an excellent weaver and craftswoman. Two different African-American men are mentioned in different sources as being her father. The first is Samuel Lewis,[4] who was Afro-Haitian and worked as a valet (gentleman's servant).[10][11] Other sources say her father was the writer on African Americans, Robert Benjamin Lewis.[12] Her half-brother Samuel, who is treated at some length in a history of Montana,[13] said that their father was "a West Indian Frenchman", and his mother "part African and partly a descendant of the educated Narragansett Indians of New York state."[14] (The Narragansett people are originally from Rhode Island.)

By the time Lewis reached the age of nine, both of her parents had died; Samuel Lewis died in 1847[15] and Robert Benjamin Lewis in 1853. Her two maternal aunts adopted her and her older half-brother Samuel.[8] Samuel was born in 1835 to his father of the same name, and his first wife, in Haiti. The family came to the United States when Samuel was a young child.[15] Samuel became a barber at age 12 after their father died.[15]

The children lived with their aunts near Niagara Falls, New York, for about four years. Lewis and her aunts sold Ojibwe baskets and other items, such as moccasins and embroidered blouses, to tourists visiting Niagara Falls, Toronto, and Buffalo. During this time, Lewis went by her Native American name, Wildfire, while her brother was called Sunshine. In 1852, Samuel left for San Francisco, California, leaving Lewis in the care of a Captain S. R. Mills.

By the time she got to college, Lewis was economically privileged, because her older brother Samuel had made a fortune in the California gold rush and "supplied her every want anticipating her wishes after the style and manner of a person of ample income".[14]

In 1856, Lewis enrolled in a pre-college program at New York Central College, a Baptist abolitionist school.[8] At McGrawville, Lewis met many of the leading activists who would become mentors, patrons, and possible subjects for her work as her artistic career developed.[16] In a later interview, Lewis said that she left the school after three years, having been "declared to be wild."[17]

Until I was twelve years old I led this wandering life, fishing and swimming...and making moccasins. I was then sent to school for three years in [McGrawville], but was declared to be wild—they could do nothing with me.

However, her academic record at Central College (1856–fall 1858) has been located, and her grades, "conduct", and attendance were all exemplary. Her classes included Latin, French, "grammar", arithmetic, drawing, composition, and declamation (public speaking).

The Specie Circular is a United States presidential executive order issued by President Andrew Jackson in 1836 pursuant to the Coinage Act of 1834. It required payment for government land to be in gold and silver.[1]

The order, which took effect on August 15, 1836, required that sales of public lands over 320 acres be paid for in gold or silver specie, except for certain types of Virginia scrip. The order aimed to curb the use of depreciating paper money from state banks not backed by hard currency, which had become widespread due to Jackson's veto of the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States. Although the Specie Circular was one of Jackson's last acts in office, its consequences, including inflation, rising prices, and the Panic of 1837, occurred during and were attributed to the presidency of Martin Van Buren. The Specie Circular also caused a split within the Democratic Party, with some members supporting sound money and others advocating for paper currency.

0 notes

Text

111 - 11I

222 - 225

333 - 33E

444 - 44P

Un Approved Clearance

[ BLACKBALL / STONE ]

555 - 552

666 - 66d

youtube

777 -77T

888 - 88 ( Skyline )

...affiliated with the wrong people

...stoned blackballed criminals

...those alligned fraudulently

999 -99P

BlackBall / Stone

000 - MAgic ( 0 )

0 notes

Text

Sir Edward Brantwood Maufe, RA, FRIBA (12 December 1882 – 12 December 1974) was an English architect and designer. He built private homes as well as commercial and institutional buildings, and is remembered chiefly for his work on places of worship and memorials. Perhaps his best known buildings are Guildford Cathedral and the Air Forces Memorial. He was a recipient of the Royal Gold Medal for architecture in 1944 and, in 1954, received a knighthood for services to the Imperial War Graves Commission, which he was associated with from 1943 until his death.

Maufe was born Edward Muff in Sunny Bank, Ilkley, Yorkshire, on 12 December 1882.[1] He was the second of three children and the youngest son of Henry Muff and Maude Alice Muff née Smithies.

youtube

Henry Muff[2] was a linen draper who was part owner of Brown Muff & Co a department store in Bradford, “the Harrods of the North”. Maude was the niece of Titus Salt, the founder of Saltaire. Maufe started his education at Wharfedale School in Ilkley, and later attended Bradford School.[3]

During his adolescent years, Maufe became interested in architecture. In 1899 he was sent to London to serve a five-year apprenticeship under the direction of the architect William A. Pite, brother of Arthur Beresford Pite.

..morman

Soon after, the Muff family moved from Yorkshire to Red House in Bexleyheath. The house was designed by Philip Webb for William Morris; Maufe later acknowledged the design as an early architectural influence. After completing his apprenticeship in 1904, Maufe attended St John's College, Oxford, where, in 1908, he received a B.A.; he also studied design at the Architectural Association School of Architecture.[3]

In 1909 the Muff family name was changed by deed poll to Maufe by Henry and his brothers, Charles and Frederick, "for ourselves and our respective issue". The deed poll stated that they were "desirous of reverting to the old form of our surname".[4][5] The following year Maufe, then aged 28, moved to 139 Old Church Street, Chelsea, London.

On 1 October 1910, he married Prudence Stutchbury (1882–1976), the daughter of Edward Stutchbury of the Geological Survey of India. She was an interior designer and later a director of Heal's.

They had a son who died in 1968.

During the First World War Maufe served in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, before joining the army in 1917 with Dick Sheppard, who acted as his guarantor.[6]

...mtima

Maufe enlisted in the Royal Garrison Artillery on 9 January 1917, was commissioned as a staff lieutenant that April, and saw action in Salonika. He was discharged on 26 February 1919.[6]

Having already been an associate member since 1910, Maufe was elected a fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 1920.[3]

In 1940 Maufe commissioned his portrait, which is now housed at the RIBA. The picture shows him in front of his winning design for Guildford Cathedral from Gluck, whose studio in Hampstead he had designed in 1932.

Another oil portrait of him by John Laviers Wheatley (1892-1955) was exhibited in 1956 and is in the Primary Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London.[7]

0 notes

Text

On 22 May 2017 at 22:15 BST (UTC+01:00), a member of the public reported Abedi, wearing black clothes and a large rucksack to Showsec security. A guard observed Abedi but said that he did not intervene in case his concerns about Abedi were wrong and out of fear of being considered a racist. The security guard tried to use his radio to alert the security control room but was unable to get through.[6] No police officers were available for members of public to approach as they had ignored briefings to stagger their breaks during the concert and instructions to be in place at the City Room entrance of the arena 30 minutes prior to the end of the concert.[7] Two British Transport Policeofficers who were supposed to be in place at the arena had gone on a 10 mile round trip to buy kebabs and were not present in the 31 minutes prior to the explosion.[8]

About fifteen minutes later at 22:31,[9]: 3.8�� the suicide bomber detonated an improvised explosive device, packed with nuts and bolts to act as shrapnel, in the foyer area of the Manchester Arena.

The attack took place after a concert by American pop star Ariana Grande that was part of her Dangerous Woman Tour.[10][11] 14,200 people attended the concert.[12] Many exiting concert-goers and waiting parents were in the foyer at the time of the explosion. According to evidence presented at the coroner's inquest, the bomb was strong enough to kill people up to 20 metres (66 ft) away.[13]

Greater Manchester Police declared the incident a terrorist attack and a suicide bombing. It was the deadliest attack in the United Kingdom since the 7 July 2005 London bombings.[9]: 3

Aftermath

About three hours after the bombing, police conducted a controlled explosion on a suspicious item of clothing in Cathedral Gardens. This was later confirmed to have been abandoned clothing and not dangerous.[14][15]

Residents and taxi companies in Manchester offered free transport or accommodation via Twitter to those left stranded at the concert.[9]: 4.85 Parents were separated from their children attending the concert in the aftermath of the explosion. A nearby hotel served as a shelter for people displaced by the bombing, with officials directing separated parents and children there.[9]: 4.85

Manchester's Sikh temples (gurdwaras) along with local homeowners, hotels and venues offered shelter to survivors of the attack.[16]

British military personnel alongside armed police as part of Operation Temperer in response to the raised threat level

Manchester Victoria railway station, which is partly underneath the arena, was evacuated and closed, and services were cancelled.[10]

[17] The explosion caused structural damage to the station, which remained closed until the damage had been assessed and repaired, resulting in disruption to train and tram services.[18]

The station reopened to traffic eight days later, following the completion of police investigation work and repairs to the fabric of the building.[9]: 4.57

After a COBRA meeting with Greater Manchester's Chief Constable, Ian Hopkins, on 23 May, Prime MinisterTheresa May announced that the UK's terror threat level[19] was raised to "critical", its highest level.[9]: 5.247 The threat level remained critical until 27 May, when it was reduced to its previous level of severe.[20] In the aftermath of the attack Operation Temperer was activated for the first time, allowing up to 5,000 soldiers to reinforce armed police in protecting parts of the country.[21][22][23]

Tours of the Houses of Parliament and the Changing of the Guardceremony at Buckingham Palace were cancelled on 24 May, and troops were deployed to guard government buildings in London.[24]

On 23 May, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, via the Nashir Telegram channel, said the attack was carried out by "a soldier of the Khilafah". The message called the attack "an endeavor to terrorise the mushrikin, and in response to their transgressions against the lands of the Muslims."[3][25][26]Abedi's sister said that he was motivated by revenge for Muslim children killed by American airstrikes in Syria.[27][28]

Manchester Arena City Room foyer, after renovation

The Arena remained closed until September 2017, with scheduled concerts either cancelled or moved to other venues.[29] It reopened on 9 September, with a benefit concert featuring Noel Gallagher and other acts associated with North West England.[30]

May announced an extra £13 million reimbursement from central government to Manchester's public services for most of the costs incurred by the attack in January 2018.[31] Later that month, Chris Parker, a homeless man who stole from victims of the attack whilst assisting them, was jailed for 4 years and three months.[32]

0 notes