a series of retrospections into the relationships we have with the media we create and consume

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

SAY CHEESE!

the association of meaning to photography as an art form and as a social right.

written by naomi✿✿✿

When you take a picture - whether it's on your digital camera, professional camera or your cell phone, do you ever think about why you decided to capture that moment in time. Do you believe that what you see is exactly what you get in photographs? Do images really say a thousand words? If they do, are those words perfectly received by all viewers of your image and do those words change with time?

I don’t really know the answer to these questions either, and to be honest they kind of contribute to the esoteric universality of photography. It shouldn't be imperative for viewers to know the exact intent behind an image, especially since we’re going to place our own narrative on it anyway.

This is essentially what the beauty of photography is; ambiguity. A constantly evolving image has many meanings, as its manipulation cannot weave its intricacies to one sole interpretation.

Susan Sontag’s In Plato’s Cave from the book: On Photography speaks of photography using many definitions. She discloses two modes of photography- as an art form and as a social right. She believes photography is a reflection of reality and is construed to show parallelity to Plato’s Cove. Where the shadows of the exterior world reflect only certain pieces of the truth.

“To collect photographs is to collect the world”, she says as she speaks of the exploratory notions of “what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe” (Sontag, 3). But there are complexities that have made modern photography mean much more than that. An image can be manipulated into the mere idea of truth.

“But despite the presumption of veracity that gives all photographs authority, interest, seductiveness, the work that photographers do is no generic exception to the usually shady commerce between art and truth. Even when photographers are most concerned with mirroring reality, they are still haunted by tacit imperatives of taste and conscience” (Sontag, 6)

Photography as an art form reflects photos in the form of expression and are an interpretation of the artist's reality. We see what they want us to see but associate our own meaning to it. While photographers may be concerned with capturing reality, the idea of satisfying niche imperatives of their own intrigue and consciousness will always hone itself into the photograph. It is a means of converting image into experience, experiences that have the ability to be more simple than we think.

PEACEFUL ILLUSTRATIONS PRESERVE FLEETING MOMENTS OF EVERYDAY LIFE -ELFIE THOMAS

In this sense the truth is stranger than fiction, because it’s undetermined. Photographic art in itself can’t always be limited to reality if we want it to create narratives that evoke thought and evolving processes.

Although photography claims to capture the essence of reality and we’re corrupted to deem it as the truth, we often forget that it can also be an interpretation of someone else’s feelings and sensibilities.

Sontag reminds us that today’s photographs are just pieces of the truth. Daily were shown so many different pictures of people we don’t know, in places we’ve never been before, unknowing of the intent behind the screen. We construct our own reality with all of this unknown information, living in our own interpretation of images, resulting in a photographic facade of manipulated image.

Art as a social right recognizes photography as an event in itself and not an encounter between the photographer and an event. Sontag says it is a peremptory right to invade these spaces and have something else be brought into the world. Think about it. When an event ends, the pictures still exist and create a small element of another world. Pictures will outlive all of humanity.

In recent years, we see picture taking becoming more of a casual activity of amusement. And as Sontag shares…

“Like every mass art form, photography is not practiced by most people as an art. It is mainly a social rite, a defense against anxiety,and a tool of power” (Sontag, 8).

I’ve developed a sort of ambivalence to her theory. It makes me wonder how our brains have evolved to support this acquisition of photography, as people will always consciously see what they expect and not what violates their expectations.

Sontag resonates with this towards the end of her piece, where she has a rant about the aesthetic notions of consumerism that photography has now reached, where societal expectations that objectify human life is at the forefront of pleasurable photographs (Sontag, 24). Despite her ferocity she ultimately concludes that...

"Today everything exists to end in a photograph" (Sontag, 24).

lol... toodles for now! ✿✿✿

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

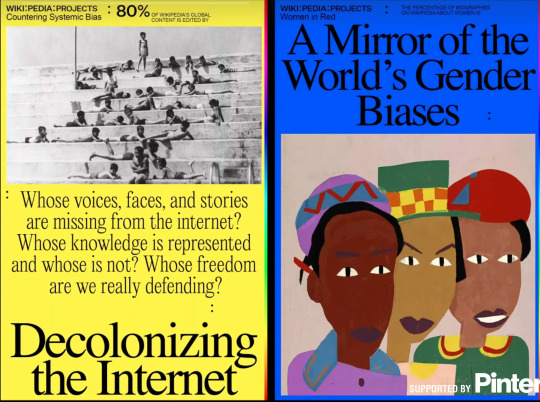

THE DIGITAL DIVIDE !

how can we decolonize technology, but make it cute ?

by naomi ✿✿✿

Colonized individuals of the new age are detaching from the post-colonial expectations and plans placed by systems of power that once dominated their peoples. All differential modes of thinking, being and existing that shy away from dominant, white-favoured Western theories have been neglected, ignored and resented. The new digital age has introduced new ways of connecting with technology and challenging what author Beatrice Martini calls the borderless colonial phenomenon. This is the infringement of rights over geographical borders that empresses the complete control over a community’s digital technology and aids in its erasure of identity (Martini).

Beatrice Martini in “Decolonizing Technology; A Reading List'' speaks about decolonizing technology and utilizing it as an avid tool of resistance against the systems of oppression and injustice that have held centuries of dominion over minority groups. It’s all about overthrowing gilded narratives of biased power to envision a world where technology doesn’t evoke colonial ideas. It is a way to de-systemize the functionality of oppressive systems with the aim to inspire and aspire the new generation to decolonize the colonial dimensions of technology.

However, Beatrice doesn’t go into deep detail about what it means to decolonize technology, but thanks to her reading list, readers are prompted to discover different perspectives that delve deeper into this enriching topic. One article that she links is written by Jessica Ogden in This is For Everyone?Steps Towards Decolonizing the Web. Jessica mentions the resolution to the digital divide not simply being about international and global inclusion in tech, that we know is already built upon predetermined and biased retrospectives, but requires a critical reconstruction of how we comprehend and understand data, the web and technology. Allowing the new digital era to challenge open-ended conceptualizations of tech that have a distinct beginning, but an unfinished ending.

ARE WE ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR WRITING THIS ENDING DIFFERENTLY?

"After all, the ‘decolonization of technology’ seems to be a conflicting term, not least because decolonization describes the retrieval of stolen land, whereas in the case of technology our concern is with the understanding of our own cultural practices" Clemens Apprich

Practical barriers of accessibility and restrictions have created the global digital divide that excludes a particular demographic from the usage and consumption of technology and digital infrastructure. Once again, excessive power and control is to blame here (boo, I don't like her). Good thing Martini doesn't like her either as she shares that this exertion of power...

“strikingly channels a colonialist exercise of control, establishing who gets to use a tool or service, and to which extent”.

The culture that surrounds technology is one of elitist standards with a need to perpetuate global dominance, led by white men who build enterprises and business models at the demise of marginalized people. Digital technology plays a vital role in the economy and social life everywhere. With transnational corporations of power continuing their adamant reinvent of colonialism in the Global South, the control of intellectual property, digital intelligence, and the means of computation are all at risk here. This is all part of the digital architecture that Michael Kwet raves about in his piece. Understanding The Architecture of Digital Colonialism allows us to really delve into the conceptual construction of colonial thought in digital advocacy, to assess what it means to decolonize it and investigate this domination that results in subordinate dependency.

Richer countries could be sharing transferable knowledge and tech and attempt to achieve global prosperity on equal and fair terms. Yet they decide to financially and institutionally support ideas that clearly lack the ability to think critically about digital culture. Technology generates a colonizing practice in the first place, proving that standard tech is driven by hegemonic structures and capitalistic politics, as a source of homophilic ideas.

So can we fix this or what? Is there a response to this messy affair? We must realize that the only way to fix these digital discrepancies is to find new ways to engage with it. The answer is always found from within. We cannot technologically advance by submitting to technophobia (that would mean you think tech is totally gross and you completely and utterly do all things to avoid it. Think of like Cher from Clueless “AS IF” gross…)🤮

DON'T BE LIKE CHER

Digital colonialism is now engulfing the world and the resolutions for the digital economy has to involve the broader struggles for equality. As technology evolves into digital infrastructures of artificial intelligence that unfairly target people of colour, now more than ever we need to work towards scrutinizing what our society deems as normal culture. We must introduce new modes of knowledge into machine research that disassembles the racial ordering that colonialism has introduced to the world.

lol... toodles for now! ✿✿✿

0 notes

Text

i think, therefore i post, tweet, share

examining selfhood and group identity formation in digital spaces

written by kaylz

Why do you post on social media? Posts can be informational or aesthetic, but the intention behind why you share your given information is the most important part. Harvard researcher, Mesfin Awoke Bekalu, writes on the power of social media to connect us to a greater audience than has ever been possible, going across physical distances and language barriers, and allowing people from varying backgrounds to interact with one another. However, he warns that the way we use social media is of paramount importance and our individual backgrounds affect whether it is truly negative or positive—with a particular disadvantage for the elderly, less-educated, and racial minorities.

So, when you’re posting, it’s important to consider what privileges allow you to post, how the content will impact or be received by a general audience, and who you want to connect with.

On the topic of connection, researcher and PhD candidate Abeba Birhane writes about how our connection with others has a greater importance to our self-identification than traditional Western thought implies. In her article “Descartes was wrong: ‘a person is a person through other persons’”, Birhane (academically) roasts Descartes – creator of the famous “I think, therefore I am” phrase – and other Western thinkers who introduced and helped standardize an individualistic and extremely rational view of the self. This Cartesian view insists that our own thoughts and conceptions of self are the only thing that matter to our identity – an idea known as cogito – excluding considerations on the impact of society and other people on the construction of our sense of self.

Birhane calls on a few examples of alternative thinking, like the Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, who thought that we could only struggle with metaphysical topics and self-conception after dialogue with others, and Ubuntu philosophy, which believes babies start with no selfhood and gain it through interactions and experiences. Rather than “I think, therefore I am”, Birhane asks readers to consider the Zulu saying, “‘Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu’, which means ‘A person is a person through other persons’”.

Social media and the Internet are epic locations for interacting with others to form our selfhood. For this generation of kids, their images and information will start being shared online before they can talk, and from young ages they will be able to engage with and post content themselves; this will have a MAJOR impact on how they understand themselves and have agency over their identities. They’re learning how to see and be seen by others in a way that will inform their views on the world, and there’s a possibility of that world as more global, diverse one because it will reflect the wide variety of content available to them in an Internet-exposed childhood. I believe this connection with others through social media and these experiences online will help children – and people in general – to shape their sense of self in increasingly unique ways, and unique people are often the changemakers our world needs.

I know right now you’re questioning how this fab idea of collective identity formation relates to a meme-page on Instagram or a TikTok thirst trap video, but give me sec to explain! As human beings we love to talk about things we’re passionate about, share experiences and information, and connect to people over mutual topics of interest. Even when those interest may seem strange, they’re something to bond over!

We can apply Birhane’s ideas about forming sense of self with others to the small communities like BookTok , fan pages for celebrities (see example here), gamers, and more. These people connect online because their aligned interests usually mean they have aligned values, personality traits, or senses of humor. However, because of their other unique interests and personal history/backgrounds, they can also learn from each other! When the different aspects of the identities of several individuals interact, those involved share discourse on experiences or see their own experiences reflected back at them through the eyes of a community member, and they see a new way of viewing themselves. This cycle can repeat, and the community connections would then impact the identities of all those involved, but we need do our best to ensure that these digital spaces are not exclusive or prejudiced towards minorities so that we all benefit from the experience.

Obvi the Internet and social media have bad parts, but that’s a topic for another blog post. Today we’ve decided to be a little less of a technophobe and little more of a techno-positivist!

TLDR: Applying Abeba Birhane’s theory on consciousness and sense of self being formed with others to social media and the Internet allows us to see them as positive spaces for improving community and self-understanding. What we post and who we connect with online shape our individual and group identities, and we should understand that as a responsibility.

TTYL, kaylz

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

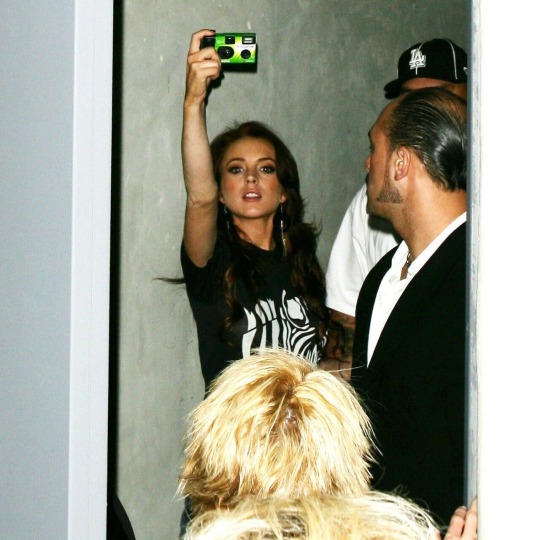

plz stop the pa-pa pa-pa-razzi!

the power of photography and media to exploit people and reinforce sexist and racist stereotypes

written by kaylz

The power of photography cannot be overstated. Pictures have the ability to shape our perceptions of the world around us and can be used to reinforce negative stereotypes and power imbalances based on race and gender. Susan Sontag and Laura Mulvey have contributed significantly to our understanding of this phenomenon.

Sontag's essay "In Plato's Cave" highlights how cameras can be used as tools of violence. She argues that photographs can dehumanize and objectify their subjects and can be used by those in power to dominate and control others. In particular, Sontag discusses the use of cameras to document violent acts, such as war or crime scenes, where the camera becomes a tool for violence rather than just a recording device. This violence can also be present in images that are not necessarily violent, such as photographs of vulnerable individuals who are being exploited for the pleasure of the viewer.

Similarly, Mulvey's concept of the "male gaze" shows how images can perpetuate harmful gender stereotypes and sexist power dynamics. According to Mulvey, the camera is typically controlled by a male director or photographer, and the images produced often serve to reinforce the male gaze. The male gaze is a way of looking that is predicated on the objectification and sexualization of women, where they are often presented as passive objects to be looked at and consumed by the male viewer. This perpetuates negative stereotypes and reinforces power imbalances, where women are seen as inferior to men.

Sorry GaGa, the paparazzi are #notcool when they take those sketchy pics of famous women. Paparazzi photographs often contribute to the sexualization and objectification of women. By objectifying women as objects of male pleasure, these pictures reinforce harmful gender stereotypes and power dynamics. Paparazzi photos often capture moments when women are vulnerable, such as when they are exiting a car or engaging in a private moment. These images use race to reinforce power imbalances and amplify the harm.

One example of this is Meghan Markle, AKA the Duchess of Sussex. Markle is biracial and has been the target of relentless attacks by the British media. She has been portrayed as a conniving, power-hungry woman trying to take down the British monarchy. The negative portrayals of Markle are a clear example of how pictures can be used to reinforce negative stereotypes and support those in power. The media is using images to perpetuate harmful gender and racial stereotypes, which ultimately reinforces power imbalances in society.

The movie "Peeping Tom," referenced in Sontag's essay, is an example of how cameras can be used to dominate and capture the suffering of others for one's own pleasure. This is what paparazzi are doing when they take pictures of famous women without their consent. They are using their cameras to invade privacy, dominate, and present women as objects to be controlled. The act of taking pictures without consent can be seen as a form of violence in and of itself, as it robs the subject of their agency and control over their own image.

youtube

So, what can be done to combat these harmful images? We need to be aware of the images we create and consume, and recognize how they can contribute to negative stereotypes and power imbalances. If a picture reinforces these things, we can choose not to create or share it. We can also call out the negative stereotypes perpetuated by paparazzi pics and demand more ethical journalism. It is crucial to promote empathy, understanding, and social justice in the images we create and consume. By using photography and visual media to uplift and empower rather than exploit and objectify, we can work towards a more equitable and just society.

TLDR: photography is a powerful tool that can be used to reinforce negative stereotypes and power imbalances based on race and gender.

TTYL, kaylz

1 note

·

View note

Text

lindsay lohan taking photos of the paparazzi with a disposable camera, 2004 📸

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

ur totally dead!

exploring digital ghosts, tools for grieving and legacies

written by kaylz

Have you ever wondered what happens when you die? Well, sucks, I can’t answer that question.

What I can talk about is what happens to your social media and online data when you die; an issue not often considered by the masses who are caught up in the present cycles of consumerism and the newest TikTok trends, or the older generation who doesn’t understand the world’s rapidly evolving technology. However, there is a dedicated following of those interested in the topic of thanotechnology, digital technology used post-death for things like memorialization.

Oliver Misraje writes about thanotechnology, how our legacies outlast us online, ghosts in the digital space and some ways people use technology to process or express their grief in the article “The Internet is a Graveyard”. Misraje explains how after we die our digital remains, the data we leave behind on social media and other technological networks, form a “HTTP ghost” of the user we were. This ghost becomes our digital legacy, offering a snapshot of insight into our curated online personality and life in the 21st century more broadly. We are constantly creating digital archives — that we don’t own — of our day-to-day lives. These can be valuable historical resources for the future if Big Tech companies (like Facebook and Apple) don't delete them, but this means that these companies control the future of our historical narrative just like they control what happens with our current data.

Often, the issue of digital legacies isn’t relevant until someone is already gone. If you’ve had a loved one pass is recent years then you may have had to go through the process of deleting or memorializing their social media accounts, which usually requires a proof of death; this may include a death certificate, obituary article, or an online will. A popular example is the Instagram account of child star Cameron Boyce, popular from the Disney Channel show Jessie, who died in 2019 from complications with epilepsy. His account still retains 12.1 million followers, but has a distinct “Remembering” banner in the bio.

Considering that 4.48 billion people use social media (that’s more than half the population!!) and there will be a projected 4.9 billion inactive accounts on Facebook by 2100, it’s important to know how to protect your digital legacy. FYI, the best way to ensure your digital accounts are handled when you die is to create an online will or appoint a legacy contact who has access to your passwords when the time comes.

Another way technology can help us come to terms with death is through emerging digital tools that help us grieve. Misraje’s article contains examples of using AI or chatbots to seek closure, trying Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy, and the terrifying prospect of Big Tech monopolizing on our digital ghosts. Underappreciated online resources also include hotlines and messaging services that support people struggling with mental health issues or crises.

Another interesting suggestion from Misraje is poetic therapy. Humans have been writing poems about loss and in memoriam of loved ones since the days of Ancient Greece, and the poetic form of the elegy was popularized during the Renaissance. It led to classics like W.H. Auden’s “In Memory of W.B. Yeats” and the lyric, “Is it romantic how all my elegies / Eulogize me?” by Taylor Swift on the bonus track “the lakes” from her 2020 album folklore.

Eulogies and elegies are similar, with the key difference being that an elegy is typically some kind of prose, but both are writings that express sorrow or melancholy – usually over the loss of a family member, close friend, or lover. Misraje’s article includes an example of how a journalist named Vauhini Vara successfully prompted GPT-3 to write about her sister’s death. With the recent explosion of popularity for AI systems like ChatGPT, why not use the easily accessible digital tools at the tips of your fingers to process overwhelming emotions like grief and explore the human ability to create emotional connection with technology?

Or, if you’re feeling technology-adverse, you can always try it the old-fashioned way and write out your own feelings with a pen and some paper. Grief is one of those nearly intangible emotions, functioning – much like the Internet itself – in an omnipresent and difficult-to-pin-down way, and everyone has to experience and process it in their own time. Yet, regardless of your comfort level with using digital tools to grieve, it’s important to understand how thanotechnology is developing and the impact it can have on your digital legacy.

Ultimately, I’ll never be able to tell you what happens when you die, but I can advise you to protect your digital legacy – and pick a legacy contact who will never show your family your spam Instagram account.

TTYL, kaylz :)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

online sovereignty: total yuck!

digital ideas of decolonization

written by zoe ⋆˙⟡♡

The digital world has come to replace the physical one in a number of aspects of our lives. This, of course, brings into question how we perceive and interact with our cultural monuments now that we have moved to a collective online space. Namely, this includes the museum.

Beatrice Martini states: “Western culture has long been defining how the world came to existence, its history, and how it works from a perspective which is centred on a Western and white point of view.” Martini continues to break down how colonial ways of thinking have shaped the online world as a reflection of our face-to-face reality. While Martini asks questions surrounding the accessibility and exclusionary practices that exist within colonial ways of thinking on the internet, I wonder how colonial institutions interact with our digital spaces and how we can find new ways to interact with our histories and the preservation of our past.

The museum as an institution has received a number of valid criticisms throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Today we view museums as educational centres and preservations of knowledge, our museums play a significant role in national and cultural identity. This also means that these institutions have power, and the power to control the narrative of our histories. The relationship to the colonial is intrinsically tied to the museum, they were quite literally created to house the ‘treasures’ of colonization during the 16th century. By the 1980s, there was a shift in museum practices but the message remains the same, these are homes of colonial spoils.

So when a museum goes online, how does the colonial interact in this digital setting? How do these collections, which museums have developed plans to reconceptualize in their physical institutions, become decolonized in the dimensions of technology? We cannot leave it unchallenged, as Martini explains, the power imbalance will continue to grow and could perhaps open new gateways for colonial powers to exert their power in this digital realm.

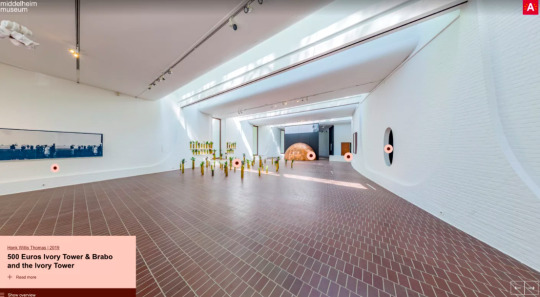

So how do we challenge this growing online sovereignty? With the emergence of the covid-19 pandemic, many museums were forced to make the swift switch to the digital world in order to survive, and one who did so while simultaneously challenging the colonial past through their virtual museum was the Middelheim Museum located in Belgium.

Once known as the Colonial College, what is now Middelheim Museum prepared students for management positions in the Belgian-occupied Congo. This provided the museum with a unique opportunity to present its colonial past, take responsibility for the histories that preceded the institution today and provide the framework for reconciliation. The exhibition Congoville has artists tracing the colonial tracks while also presenting the vibrant and flourishing central African culture.

The exhibition can be accessed through their website and through VR, creating a visual archive that will remain accessible for years to follow. The exhibition was–and continues to be–a success. It was new and refreshing for artistic communities but most importantly it presented a step towards a decolonial digital space. I strongly believe online spaces like Middelheim Museum would be a strong addition to Martini’s reading list and simultaneously provide museums with an opportunity to reshape their identity, moving away from the oppressive colonial world that predates them and moving towards a progressive and decolonial digital world.

brb zoe⋆˙⟡♡

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

video games, hot or not?

gender-based violence in online spaces

written by zoe ⋆˙⟡♡

Video games, the violent, dangerous and unknown. Or at least, that is how the world of electronic adventures has become intrinsically linked to accompanying violent actions.

But what is it that correlates with this belief? And furthermore, why is it that these spaces have become totally macho, and would probably smell a bit like axe body spray if they were in-person environments, don’t girls get to have a little fun too?

Despite men and women playing video games in equal numbers, the world of video gaming is strongly associated with masculinity. A common stereotype and one often used to justify misogynistic practices in online spheres, female gamers are thought of as less skillful and casual players as opposed to their male counterparts. This marginalization of women in digital spaces has roots leading all the way back to the creation of the internet itself, as explored in Mar Hicks’ article A Feature, Not a Bug.

Hicks explains the relationship computing industries have with meritocracy, that the wider world pleads the idea that these high-tech industries are not predicated on skill and intelligence, these systems concentrate power, the clearest example being in gender-based discrimination on the basis of sexuality. Female workers were, and continue to be, seen as women, which meant they are viewed as less intelligent despite the fact that women have been foundational to not just high-tech industries, but have impacted technological advancements that are rarely recognized or credited.

Similarly to the way high-tech industries influence much of modern media and culture, in the world of digital online spaces, they influence the way users live, work, consume and create. Advancements in tech have enabled us to contact and connect around the globe. This has, in turn, also led to an increase in gender-based violence against women within digital spaces. This personalization of video game spaces is why we can see this gamer identity has so many die-hard fans trying to make their girls' out signs as literal as possible.

These spaces provide an environment for young boys to express themselves with little to no resistance, allowing one another to fuel their biases to extremes. Almost all professionals and highly visible figures in gaming are male presenting, their female counterparts are often marginalized, frequently being on the receiving end of much hatred and sexualization. These mindsets and rationalizations exist both inside and outside gaming culture, just as they are used to drive profit, “developers pander to a male consumer base with strong male characters and sexy female characters” (Paaßen).

In order to combat much of the harassment faced online, many women will take on alternative identities, either presenting as male or gender non conforming. The game industry itself plays a huge role in the promotion of these ideas, much like many tech industries continue to view women as replaceable and disposable assets, this mindset has become ingrained into many online spaces.

There is no space for harmful actions against women in the online world. Digital violence has had a severe impact on women and girls, both their mental and physical safety have time and time again come into concern for female-identifying people trying to navigate online spaces.

It is important that we uplift voices in gaming communities that are trying to combat this gender-based digital violence. There is a tendency to not take online violence seriously, but what happens in an online space can easily be reflected in an offline one. These views and actions do not end when the computer is shut off. While it is essential to not let our fear of the unknown video game world win, it is still important to recognize how we can combat the hatred and negative practices that exist to make these spaces more enjoyable for everyone.

brb z0e ⋆˙⟡♡

0 notes

Text

are old people like #cancelled from cyberspaces?

ageism in the era of digital platforms

written by naomi ✿✿✿

When speaking of media ideologies and perspectives and analysing them through our own unilateral opinions, we often neglect certain biases that occur through digital platforms. The construct of media has evolved over the decades, and social media as we know it could never be stagnant. With that, the world has overlooked certain normalized deviances that affect the way all people socially ingest media. Yet, it seems that there is no advert concern with the generational learning gaps of technology and age-related stereotypes towards its usage. In “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace” written by John Perry Barlow highlights “the new home of mind”, which is identified as cyberspace. This new outlook on cyberspace and technology refuses to be held under governmental regularities and refuses all holistic approaches of control and enforcement. It renders itself as a quest to investigate the relationship between the discrepancies of age and technology at the hands of an ever changing cyberspace.

Perfecting digital technology has become a vital pillar for what it means to be a fully fledged member of society. I mean I vividly remember re-taking Snapchat selfies with my grandmother because she had to “make sure her WhatsApp story was on point”. Yet, I lack much familiarity with Facebook so I couldn't help her out with the new update they’ve launched. This specific encounter intrigued my interest on whether my grandmother, and possibly other elderly people struggle with their daily usage of technology. Are new updates and tweaks accessible and apprehendable to them? Are they able to buy the newest IPhone because they would know how to use it, and not because it’s the newest IPhone?

It seems as though older people are not considered in the algorithms on digital platforms. Every technological advancement aims to be faster, smarter and desired, ultimately making it more feasible but less adaptable. There are algorithms put into play that hinder older people’s accessibility to the internet and technology because they are tethered towards the youth. Ageist paradigms like these affect the digital intelligence of a group that under the Independence of Cyberspace, should be included, heard, and recognized. But the advancements made toward technology don't seem to reflect that, which is really an #EpicFail㋡

Negative preconceptions and fixed beliefs about older individuals have caused them to be undervalued, ignored, and left out of the grander scheme of digital platforms. These perceptions are shaped by the values and approaches used in the design process, a process that rejects a diverse, accessible and just cyberspace. As a result, digital platforms may unintentionally or intentionally perpetuate this form of bias by failing to consider the preferences, and circumstances and normalities that older people encounter in their daily lives through the process of aging. Barlow emphasizes in his impenitent soliloquy ( pretty much a rant) that cyberspaces should not and cannot leave anyone out of the retrospective space of media that they are creating, as they seek a world that “may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth” (Barlow). I resonate with his passion toward the diversity and inclusion of cyberspace and its fascinations, making readers like myself question the freedom that individuals have within technology and cyber spaces.

Cyberspace Independence speaks of this global conveyance that relates the human mind and its creations being reproduced and distributed at no cost (Butler). If we view the consumption of technology this way, we could account for the transparent chasm between the younger generation and the older generation, where the barriers of technological engagement are defined by the period in which you entered the earth. The circumstances of technology do not make the future of digital life promising and makes me wonder whether the world will see a vast shift in the demographic of digital users. There are certain steps we can take towards addressing the barriers for internet use among the elderly and what can be done to address and change these conflicts.

Technology always seems to be concerned with the future, but not so much who takes part in it. What does the future look like for older people when they feel uncomfortable using something that dominates their world? Who has the right and the power to change this narrative for them? Investing in infrastructure that allows elderly people to overcome the barriers they have surrounding internet could be a crucial start. In the wise words of Butler, “... no one can arrest our thoughts”.

lol... toodles for now! ✿✿✿

0 notes

Text

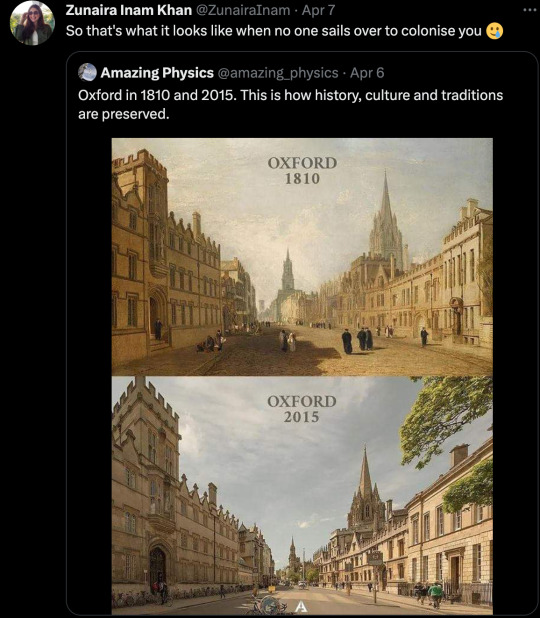

Bernini is #Overrated

enduring relevance & classical art

written by z0e ⋆˙⟡♡

After rea Rachelle Hampton’s article, The Black Feminists Who Saw the Alt-Right Threat Coming, her analysis of the complete failure of mainstream media to identify the rising threat of alt-right trolls and online extremism spread through blatant misinformation campaigns are unfortunately echoed through many other subsections of the internet.

Last month, the section of Twitter I found myself a part of had one of Bernini’s iconic sculptures at the centre of mass debate. I found myself beginning to feel like the women from Hampton’s article–it was clearly a bait tweet, one that tries to make the viewer feel angry or inadequate for a reaction. It was when I realised that the tweet had over 500 million views that my attention was drawn in. @Culture_Crit tweeted “A 23 year old sculpted this. What’s your excuse?” paired with a picture of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s sculpture entitled The Rape of Proserpina.

Upon first glance, one might simply disregard the tweet but as user @theobromic_ replies, “bernini was raised by an established sculptor acquainted with the pope himself and was brought to rome at age 8 to receive the best training one could ask for in renaissance italy, never needing to study or work in any other field” and makes an excellent point. The art world–which has been consistently gatekept by classism and money–marks its elitism through this type of socially manipulative behaviour in which glorification of the classical world becomes harmful. This projection of modern-day identity politics onto classical works is found at both ends of the political spectrum, but is used predominantly in right-leaning, trad-fascist online groups to promote an ‘idealised’ idea of a white-supremacist society.

As Dr. Futo-Kennedy explains, there are structural elements within the field of classical studies to support and maintain whiteness, such as success in relation to language knowledge, the apologetic approach to slavery in the ancient world from a 19th-century European worldview, and the continued practice of using textbooks and dictionaries that were created during the 1800s where deeply rooted ideologies of European superiority become intertwined with the teaching of the subject.

With a deeper glance into Culture_Crit’s profile, we begin to see these themes of white supremacy begin to surface. The January 12th tweet reflects more than just an expression of lost value in the creation of art, tweet after tweet expressing their hatred for modern art and architecture, promoting their lovingness to right-wing Christian ideologies and associating contemporary art with a diabolical left. Due to these foundations to the field being so deeply rooted in ideas of whiteness, these actions are continuously enabled. By guising their opinions as missing ‘what we once had’, Culture_Crit, like many others, is able to hide behind a false idea of cultural perseverance while promoting white supremecist ideologies.

In a later post, Culture_Crit compares Giuseppe Sanmartino’s sculpture, Veiled Christ, to Duchamp’s Fountain, captioning it as “Art in a religious society [compared to] ‘Art’ in a Godless society.”

Known by some as the face of Dadaism, Duchamp’s anti-war sentiments expressed in his early modernist work clearly still baffles audiences today, but Culture_Crit’s tweet is more than just a critique of the technical aspects of modernist art. Fountain is a rejection of European values during the early 20th-century, and its traditions. The authority, violence, racism, nationalism and capitalist society is exactly what Duchamp wanted to reject, and is something that makes many like Culture_Crit uncomfortable. Art like Duchamp’s, and the thousands of artists that would come to follow, through their work challenge these systems and attempt to uproot these long-held beliefs by rattling the art world, which in turn affects all of the media we consume.

When approaching Culture_Crit’s tweet through a critical lens, clear discrepancies begin to emerge. But this is not always the case with an online viewership. Very quickly and very easily can viewers be swept up into these deep spirals of hatred that initially mask themselves as valid sources of critique.

works cited

brb z0e ⋆˙⟡♡

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Stickers featuring the cartoon version of Lizze McGuire, taken from “My crush-tacular book of valentines” published by Disney in 2003

3K notes

·

View notes