Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

‘Musical Schemas in Capoeira Music - an Analysis of Mestre Pernalonga’s Performance of ‘Parana ê/A Manteiga Derramou’ - PART 2

‘A Manteiga Derramou’

The corrido ‘A Manteiga Derramou’ is the second corrido of the performance. The four bar chorus response melody is fixed and can be seen below, alongside the chorus in Pernalonga’s performance which once again features a strong upper third harmony:

Transcription 10.

When analysing the verses I have chosen to look at a recent recording made by Mestre Suassuna, alongside a very old recording by the founder of one of the three branches of capoeira, Mestre Bimba. In Mestre Suassuna’s performance very different melodic contours are used with the text. The first is on the beat and each phrase clearly passing through the next barline and is centred around the 5th, 3rd and tonic of the pentatonic scale.

Transcription 11.

The second however is more syncopated and uses the first three degrees of the scale only.

Transcription 12.

We can compare this to Mestre Bimba’s performance which is much lower, centring on the 3rd and 5th (or 6th) notes of the scale:

Transcription 13.

It is also interesting to note at this point that all three reductions start the phrase on a different degree of the scale (the 5th, tonic, then 3rd).

A reduction of Pernalonga’s melodies only reinforces this point as we see below that he favours starting on the 6th degree of the scale:

Transcription 14.

We see here that the notes used are not a fixed schema, however the phrase length and overarching descending shape are constants seen across all examples. Mestre Bimba’s performance, while favouring a smaller range of notes lower down on the pentatonic scale, also features much more rhythmic variation than that of Mestre Suassuna:

Transcription 15.

In this much earlier recording of Mestre Bimba he is frequently swapping between simple and compound time which is a clear link to an older more African derived style of playing; as Charry describes a typical feature of West African music as subtle changes between binary and ternary divisions of the beat (Charry. 2000).

Mestre Pernalonga’s most used rhythmic variations show a move to triplets at the beginning of the phrase then returning to simple time. When paired with his much higher starting notes we can see that he is both experimenting with his choice of pitch, yet also adding a more traditional African feel through triplet variations.

Coda.

The final section is an instrumental ending to the performance in which greater variations of rhythm are heard in the medium and viola berimbau parts

Conclusions

This analysis shows sections within a capoeira musical performance have different schemas and therefore different expectations. Structure, phrase length, descending melodic contour and chorus responses are fixed whereas pitch (within the pentatonic scale) and rhythm allow for variation. This creates musical tension as some of these elements are set off in relief from the schema (Tenzer. 2006).

Mestre Pernalonga retains the reputation as a skilled musician through his navigation of elements to leave and others to change. We see him using his upper vocal register creating new melodies often, offsetting this with a more traditional style of compound time rhythmic variations harking back to Mestre Bimba’s original recordings. However he does this within established fixed schemas.

The spectators around the roda and capoeiristas inside it all intact learned behaviours in relation to the Ladainha, Louvação and Corridos. The schemas identified in each of these sections are important for listeners as they allow them to form an understanding of what has been heard (Widdess. 2013.) In capoeira it also affects physical movements in the roda, and as the schematic structure of the music unfolds, all participants are therefore involved in an interactive process of musical communication (Widdess. 2013) which in turn passes on the music and these schemas to the future generation of capoeiristas.

Appendix.

Structure diagram: This shows a left to right (landscape) visual of the piece with each block representing a section. Time codes, section names and some stand out details are included. This gives an overview of the piece in its entirety.

Transcriptions:

1: Mestre Pernalonga’s Ladainha. Brackets show phrasing. The opening shout is notated in the beginning before the barline. This reduction is shown in a free time as the rhythms are not the focus of the transcription, it is the melody and contour.

2: Three rhythmic variations are shown. A two line percussion stave has been used to show the two pitched notes of the berimbau, higher and lower, with the percussive sound of the hand held stone muting the wire string notated with a crossed note head.

3: The pandeiro and atabaque are shown respectively on a one line percussion stave. The letter B marks a bass tone and S a slap tone. Crossed note heads with arrows underneath show directional movement of the pandeiro to make the metal disks rattle and the higher slap is notated with a crossed note head to show its force - but written above the stave to differentiate it from the metal disk rattles.

4: Call and response recorded by Mestre Pastinha. The note labeled 1 gives A as the root and further numbers indicate the degrees of the scale to aid analysis of this reduction.

5: Three variations are shown in a reduced form. The first Bb is given in brackets as a root note reference point. The descending line coming out of the 5th degree note in the third bar marks a bending of pitch on this note, falling to an undetermined lower pitch.

6: Two variations marked 1 and 2. Notes are numbered to clarify their degree of the scale, with lines stretching where the note degree stays the same.

7: Mestre Pernalonga’s version, with harmony line added in an upper part with ascending note stems.

8: Roman numerals mark implied harmony. In this reduction diagonal lines are used between note heads to reinforce the direction of the melodic contour. The blue markings show where a harmonic difference of a 3rd is present.

9: Asterisk markings over the bracketed final two bars of the first two variations show that these two sections are often interchanged.

10: Two notes in bar three with upper facing stems show a harmony part that is often performed.

11: Marked 1 for part 1 and R1. for ‘Reduction of 1’. Diagonal lines outline the bar crossing contour and degrees of the scale are numbered.

12: The reduction shows that lower degrees of the scale are used in this version and without regular bar crossing contours.

13: This reduction shows contours using diagonal lines to link the note heads. 5/6 and 6/5 show that these are the options most used and are swapped frequently by Bimba. This has been written as a reduction down to melody and pitch rather than rhythmic placement of each note in the bar as Bimba’s performance is very irregular and in an almost spoken form. The observation of the contour and pitches are more important here.

14: Here the barlines divide each phrase to show them separately, rather than dividing a set unit of measurements.

15: Three variations are shown each marked numerically 1-3. This is shown on a single percussion stave.

References:

Brown, S. Jordania, J. (2011) Universals in the Worlds Musics. Psychology of Music.

Capoeira, N. (2006) A Street-Smart Song: Capoeira Philosophy and Inner Life. Blue Snake Books.

Capoeira, N. (2002) Capoeira: Roots of the Dance Fight Game. Blue Snake Books.

Capoeira, N. (2003) The Little Capoeira Book. North Atlantic Books.

Charry, E. (2000) Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of West Africa. University of Chicago Press.

Stock, J. (1993) The Application of Schenkerian Analysis to Ethnomusicology: Problems and Possibilities. Musical Analysis Journal.

Tenzer, M. Analysis, (2006) Analytical Studies in World Music: Categorisation and Theory of Musics in the World. Oxford University Press.

Widdess, R. (2013) ‘Schemas and Improvisation in Indian Music.’ In: Kempson, Ruth and Howes, Christine and Orwin, Martin, (eds.), Language, Music and Interaction. London: College Publications

Zadeh, C. (2012) Formulas and the Building Blocks of Thumrí Style - A Study in Improvised Music. Analytical Approaches to World Music

Audio:

Mestre Pernalonga (2017) CD. Capoeira Musica. N/A, self published and produced.

Track 2: ‘Parana ê/A Manteiga Derramou’

[Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=px3es0z1uDs] [Accessed, 30, March. 2018] Image 1.

Mestre Jogo de Dentro ‘Parana ê’

[Accessed online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L8z8YkfMDr4] [Accessed 30, March 2018]

Mestre Suassuna. ‘A Manteiga Derramou’

[Accessed online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BdjAH4Qbhss] [Accessed 29, March 2018]

Mestre Bimba. ‘A Manteiga Derramou’

[Accessed online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=usf5TCDTMU4] [Accessed 29, March 2018]

Mestre Pastinha: ‘A Manteiga Derramou’

[Accessed online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_UY0vyB7HNE] [Accessed 28, March 2018]

Grupo Muzenza de Capoeira: ‘Parana ê’

[Accessed online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y3GLBvmEv7s] [Accessed 28, March 2018]

Images:

Image 1: Mestre Pernalonga (2017) CD. Capoeira Musica. N/A, self published and produced.

0 notes

Text

‘Musical Schemas in Capoeira Music - an Analysis of Mestre Pernalonga’s Performance of ‘Parana ê/A Manteiga Derramou’

Image 1: ‘Capoeira Musica’ CD. Mestre Pernalonga

Introduction

The Afro-Brazilian martial art ‘Capoeira’ is unique as a mixture of a dance, fight and sport, ‘played’ with musical accompaniment. The ‘game’ itself takes place in a circle on people called a ‘roda’ with musicians playing percussion and three sizes of berimbau to one side, and the entire circle of spectators participating in singing songs lead by the musicians. The acrobatic movements made by the players in the roda reflect the rhythms and overall mood created by the musicians (Capoeira. 2003). This essay will analyse a performance of a set of songs performed and recorded by Mestre Pernalonga and through the use of Schenkerian style reduction analysis will examine the schemas present in the performance.

Capoeira music is an oral tradition and it is of interest to compare different versions of the same songs to examine which schemas are fixed and which allow adaptations, and to what degree. As the writer Nestor Capoeira states:

‘Its a bit like jazz, where each time something different comes out although you are playing the same theme. (Capoeira, 2002. p.g 6)

However these themes are never fully defined other than by subject or text. The aim of this essay is to define the themes used and to explore which elements are changed and which are maintained between versions. I compare Mestre Pernalonga’s performance to established ‘classic’ recordings by capoeira’s founding fathers Mestre Bimba and Mestre Pastinha (Capoeira. 2006) as well as with contemporary recordings. In recent years contemporary recordings have gained a favourable reputation through transmission between groups and natural rises in popularity. The examples I examine hold a high number of online ‘views’ as proof of their legitimacy.

Structure

Much like examples used by Tenzer in his world music analysis, Mestre Pernalonga’s recording should not be seen as a piece of music but as a performance. The function of capoeira music is to create a specific energy through the berimbau, the rhythm and the singing (Capoeira. 2002) which instructs the speed and style of physical play inside the roda.

Performances start with the ‘Ladhaina’ introduction section, then established call and response based songs are strung together as a set. Zadeh notes the principle function of using pre memorised material in a performance as allowing the music to keep going when there are demands for constant sound for an extended length of time (Zadeh. 2012). This is the case in capoeira performance as multiple players will play in the roda within one musical performance.

A visual outline of Mestre Pernalonga’s recorded performance showing the sections:

Analysis

Stock identifies that the underlying structures that music can be reduced down to must be musically meaningful (1993) and that this may differ from one culture to another. To address this I am reducing melodies down to the most frequent pitches and referencing them to degrees of the pentatonic scale used in the capoeira tradition.

Stock cites Cook’s wariness to use reductive analysis with world music styles due to the position of the musicologist and the possible failure of understanding what the culture of study rationalises to be of musical significance, which can in turn lead to misunderstandings (Stock. 1993). I see this as a valid warning, however part of a continuum of which at one extreme is understanding the culture of study and the other is othering them. As a capoeirista myself, I am part of the culture in question so am able to make decisions with regard to aspects of the music that are significant.

My schenkerian-inspired reductive analysis looks at universals of pitch in different sections of the performance, then makes comparisons with Mestre Pernalonga’s performance to identify which schemas allow changes and which are fixed. From comparing these universals I aim to identify musical criterion by which he is held in high regard as a capoeira musician.

Ladainha

After a brief introduction from the berimbau the Ladainha story telling section starts, in which the lead vocalist signals their entrance by shouting ‘iê’ which deters others from also starting to sing (Capoeira. 2002.). There is no set melodic formula for a Ladainha, however it has a quatrain form and phrases leap up the pentatonic scale then descend down to the tonic, as is a fingerprint from the music’s origins in West Africa.

Mestre Pernalonga’s Ladainha below follows these established schemas. The notes transcribed show the most prominent pitches he uses in his phrases, and these show an extensive use of the descending major pentatonic arpeggio. Notes 1, 3 and 5 are clear and the 6th note of the scale is marked as the highest note:

Transcription 1. (See Appendix for all)

Louvação

To end the Ladainha the word ‘camará’ is called and the capoeiristas start to play in the roda as the Louvação section begins. Vocally this section follows schemas of structure, phrase and pitch. It is also in this section that we hear the full percussion section added each with a defined role. The low ‘gunga’ berimbau establishes the groove with the atabaque drum. The medium berimbau then plays an exact rhythmic inversion of that played by the gunga. The highest berimbau named the ‘viola’ plays improvised patterns on top. (Capoeira. 2002)

Transcription 2.

The pandeiro supports the atabaque and accents the fourth beat of the bar. The berimbau is played with a shaker in hand which gives an added timbre and this can be seen in isolation below which clearly shows ago-go rhythm almost in unison.

Transcription 3

All instruments in the capoeira ensemble are fixed in pitch so only able to improvise rhythmically. The roles of these instruments allow for different degrees of improvised rhythmic flourishes which comment on the game being played before them. These range from the viola and medium berimbau which do this often, to the pandeiro and ago-go parts showing infrequent variations, and the atabaque and gunga which rarely change as they are considered the driving heartbeat of the music.

Below is a reduction of the call and response pitches used in a Louvação by Mestre Pastinha:

Transcription 4

The call follows a descending contour which can have some variation between the 5th, 4th and 3rd notes of the pentatonic scale. The response however is constant, starting on the 3rd and falling to the tonic and 2nd. Three variations of Pernalonga’s call parts are shown below and show that the response part is a fixed schema, however it is only the pitches available and phrase length of the call that is set, with room for anacrusis and some slight rhythmic variations.

Transcription 5

Widdess highlights musical elements that are recalled when a memorised text is performed, known as ‘combined restraints’ (2013). In this performance the text, phrase length and direction are all established schemas, and any variations or improvisations must therefore exist within these structural restraints. Through seeing the similarities in Pernalonga’s performance compared to that of Mestre Pastinha we see the function of the Louvação itself as a large scale schema. The Louvação is when praise is given to various masters and saints, however on a practical level it is a moment where the chorus starts to participate in answering vocal phrases.

‘Parana ê’

After a short instrumental section the ‘corrido’ section starts and is defined as containing alternating call and response lines. In the song ‘Parana ê’ each line consists of four bars in 4/4 time. Chorus responses follow the same rhythm and phrase length however harmonies can be improvised with the most commonly used shown below:

Transcription 6.

Mestre Pernalong’s performance clearly combines both of these lines together with Pernalonga himself taking the top harmony line.

Transcription 7.

When comparing reductions of the verses to this song an implied harmony has been added above the staves and we can see a common trend of which degrees of the scale are favoured per bar as well as major 3rd harmonic links marked in blue.

Transcription 8.

By comparing these trends to the three most used variations by Pernalonga we can see that his performance is based on three different versions. A standard template labelled ‘1’, a low variation labelled ‘2’ which builds tension in the second bar by staying on the 2nd degree of the scale, and a third variation labelled ‘3’ in which he starts on the octave and descends, one again highlighting the 6th degree of the scale, before dropping down to finish.

Transcription 9.

From these three variations we can see that the implied harmonic changes and four bar phrase length are fixed restraints in the song, however the choice of notes in the melody allows a greater degree of freedom and artistic variation. In the performance by Pernalonga we hear him using and perhaps highlighting his upper vocal register.

0 notes

Text

‘Walakandha Ngindji' Transcription.

Walakandha Ngindji Notes

The opening bar is in free time with the didgeridoo starting and the first percussion note marked at the end of the first bar. The percussion line is on a percussion stave with the vocals and didgeridoo on standard treble clef staves. I have divided the piece into sections A, B and C. The main melody is sung in section A, a second melody in section B and a percussion section at section C. Section A is divided into A.1 and A.2 to show that there are two phrases that are very similar but not direct identical repeats. A3 is marked as it is a free time variation of the melody presented in the A section. The Didgeridoo plays constantly throughout the piece. fluctuating between an E/Eb continuous drone. The first fully notated bar is repeated with variations for the majority of the piece, with a change at letter C, which is then used with variation until the end.

Section marked A.1.

Double stemmed notes in the percussion part show where the sound heard is stronger and alludes to two sticks played together. Without a visual guide the exact nature of the percussion instrument and number of players is unclear. For this reason I have notated it as one part and used double stems and flams.

The vocal part has square brackets over the end of the third and fourth bars of phrase one in A, the second and third bars of phrase two and later in A1. signal two voices singing together. The second voice is faint in the recording and generally sings in unison with the lead voice, with a few small differences in intonation which I feel are of interest as a textural affect only.

Section Marked A.2

In the first bar the two lines above the minim represent a slight sharpening then flattening of the note during its duration.

Section Marked B.

At B the last crotchet of each triplet group features a descending curved symbol to represent a slight fall in pitch.

Section A3.

This is marked ‘Rubato, Freer Pulse’ and is without a time signature. The rhythms therefore serve to outline the phrasing of the vocals.

Section C.

The sense of regular pulse returns with the percussion part playing. The second semi quaver in each group is marked with a line above it to show that the timbre of the note is higher than the notes preceding and following it in the grouping. Again, as the number of players is unknown from just the recording, this is a representation of the rhythm and timbre based on the sounds heard.

0 notes

Text

East Anglian Folk Music: Realities, Context…and Reinvention?

Abstract:

Scottish and Irish folk music are known internationally today however East Anglia in England lacks both regional identity and folk music culture. Initial English revivals aimed to create a national culture focussed on a narrow selection of music, excluding and sub-categorising progressive elements as they developed. Ireland and Scotland exported their traditional music via the world music market, created strong musical institutions and embraced developments and innovations from their diasporas. In East Anglia my field work sees a range of non-folk repertoire accepted in folk clubs when played acoustically, popular sea shanties regarded as separate, and greater accessibility in Irish traditional music. This essay examines the theory behind music revivals, noting the key elements of recontextualisation, authenticity and what the term revival really means. I use case studies of folk music revivals in Finland, Sweden and Hungary to create a framework of initiatives including re-organising the wealth of existing yet inaccessible online resources, and instrument revival. I argue the fundamental impetus must be to create new, relevant folk music, whilst maintaining the traditional. I argue for the reinvention of the East Anglian folk music scene for the wider positive social changes I believe it could contribute towards.

Chapter 1 - Introduction

1.1 Project aims

I’m a musician and I grew up in North Norfolk in England, part of an area known as East Anglia. Celtic punk music from the 90s eventually lead me to contemporary UK folk artists such as Seth Lakeman, Eliza Carthy, Julie Fowlis and Cara Dillon, and I noticed that the UK folk music scenes are highly regional with frequent reference and importance given to places by performers, critics and presenters. Yet where was East Anglia?

The composer Vaughan Williams collected numerous folk songs from the area in the early 1900s, so at this time there must have been a regional folk music scene, but I had no experience of it during my upbringing. What happened?

My recent studies regarding the application of music for social development lead me to think about community development through music. East Anglia is not a wealthy region of the country, but could folk musical initiatives create greater community cohesion? Could this build a modern sense of identity I notice was lacking during my upbringing there?

Could folk music initiatives lead to cultural tourism and the multiple benefits that would come with increased financial provisions for the area?

Nicholas Cook, that music 'can be understood as both a reflector and generator of social meaning[…]Music, in other words, becomes a resource for understanding society’ (Cook, 2003. p.g 213) Tying these areas together my research questions for this study are as follows:

Why is folk music in England received and experienced so differently to folk music in Scotland and Ireland?

2. What is the folk music scene in East Anglia like at present?

3. What are musical revivals and how do they work?

4. Theoretically how could folk music be revived in East Anglia?

1.2 Literature Review

Folk Music Definition

Defining what folk music means to me is fundamental to this study and my definition comes from a collection of different sources. In ‘The Study of Folk Music in the Modern World’ Philip Bohlman defines folk music as rural music taught without being written down and distinguishes the difference between rural and urban calling urban music popular music and city music folklore (1988, p.g 1) I disagree with the music only being rural and oral, and believe urban music should be included as folk music. I do not see the oral nature of transmission as essential, however I recognise that a large proportion of folk music comes from an oral tradition. A fundamental perspective from Bohlman’s writing is the misconception that folk music is static (1988. pg. 3) which I agree with.

Mark Slobin supports the view of folk music changing over time and looks specifically at the content of the music:

‘Folk music: acoustic instruments with a hint of social significance. Generations reshape and revive this model at any time (Slobin, 2011. pg. 1)

This idea of content is then expanded upon when he outlines the themes covered in folk music being: work, raising children, family ties, voicing beliefs/ambitions/hopes/identities and defining and reinforcing a place in society (2011). He has also mentioned here a key instrumental identifier that is almost unanimously agreed upon: folk music instruments are acoustic. To further illustrate this, along with self identification Ruth Finnan observed the importance of musical style over choice of instrument for defining a genre, noting how learning by ear and certain playing techniques defined a level of ‘folk-ness’ (Finnan, 2007. pg. 66)

To summarise, my opinions on folk music are:

1. Folk music is both rural and urban.

2. Folk music varies and is not static.

3. Lyrics contain social significance.

4. Acoustic instruments are widely used.

5. Self identification by the performers is crucial.

6. Musical and stylistic elements from British traditional music are used.

My Own Research

The English folk song revival movements in England, Scotland and Ireland have been well documented and my study includes both contemporary and period sources. I pay particular attention diasporic folk music developments as I believe this to be relevant and my own experiences of folk music stem from these movements particularly. No one has yet written about East Anglia in specific relation to Scotland, Ireland and the rest of England, however given the scope of the study I have had to condense this project on the basis of practicality. For more concrete conclusions, in depth comparisons with regional folk music scenes across the country are needed yet are logistically unmanageable. For this reason I am focusing on understanding the events that took place in folk music revivals in the UK in the past to try and explain the differences in folk music practise between Ireland & Scotland, and England today. I then take my own observations of both the English and specifically East Anglian folk scene at present and, through the lense of organised revivals, explore possible frameworks that could be used to benefit the region, should further revival initiatives take place.

Schema

My frame of reference for understanding observed behaviours in my field work is based upon the concept of schemas which I discovered through the writing of Richard Widdess. He explains that:

‘Music seems to be composed of a large variety of specialised schemas[…]They consist of categories…between which they establish static or temporal relationships[…]They can be hierarchically combined, and generate expectations.’ (2013. p.g 200)

I keep this in mind when observing performance practises in sessions and in making correlations between the behaviours I observe, however a detailed examination and definition of the schemas is beyond the scope of this study, but would be an interesting future study.

Revival

I explore revival using Caroline Bithell’s six themes for revival, alongside Owe Ronström’s authenticity framework. The works of Juniper, Livingston and Slobin are foundations upon which I view revival in this project. The case studies I examine are centred around folk music with similar features, to create a framework of possible initiatives to increase East Anglian musical culture.

1.3 Methodology

My method of collecting primary source data is through informal conversations and observations, and to record my findings in a close up descriptive style. This style was greatly influenced by Louise Meintjes’ Sound of Africa! (2003) in which the style of prose is largely through first person observations. The author labels this as observing the symbolic aesthetic realm (Meintjes, 2003, p.g 9) which Jeff Todd Titon supports stating that:

‘Interpretation of meaningful action as a text requires that the ethnographer inscribe the observed action into a narrative description-interpretation’. (2003, p.g 177)

The study of English folk music raises an ontological problem in that there is no one dominant description or set of parameters for what English folk music is. The genre exists somewhere within multiple definitions based on musical features, performance style, and the history and origins of the material. To tackle this I have to outline my own definition of folk music and epistemologically base my primary research on empiricist observation and belief, which I join with historical study to construct more rationalist leaning questions for further study. It is the aim that should these further areas be studied, more concrete definitions would in turn arise and allow more rationalist analysis within English folk music.

Chapter 2 - Historical Context

2.1 The First English Revival

Initiatives in English folk music revival occurred multiple times from the end of the 19th century to arguably the beginning of the 21st century. To understand folk music in England today and to make UK comparisons it is crucial to understand what happened during these revival movements.

In 1898 Cecil Sharp established the Folk Song Society (FSS). A group of amateur song collectors, their intention was to collect folk songs from rural areas of England which they believed were near extinction. The organisation made the distinction between composed music and music of an oral tradition, defining folk music as music born in the mind and avoided printed sources (Keel. 1948).

Sharp pushed for folk dance to be added to the national curriculum (which it was in 1906) after becoming increasingly interested and involved in English Morris dancing and establishing the Folk Dance Society in 1911. Publications by the Folk Song society in 1912 feature the inclusion of Scots Gaelic, Canadian and Irish folk songs amongst others, however after amalgamating in 1932 (becoming the English Folk Song and Dance Society) the focus changed to repertoire and practises from England.

Sharp believed that the communally transmitted folk song contained national character which, if used strategically in education, would promote a musical and national revival (Francmanis, 2002). Sharp’s 1907 publication English Folk-Song, Some Conclusions clearly states the musical features of English folk music he observed. Although he then suggests reasons for these features based on little or no evidence, in their own right they are of interest as they define what this first revival regarded as musical features unique to English folk music (see appendix 1).

At the end of the publication Sharp’s involvement with the movement are realised. He praises other European countries for their nationalist movements and criticises, in his words, England’s tendency to culturally honour the foreigner (Sharp. 1907. p.g. 127). He sees the need to create new nationalist art music attainable through building musical good taste in children:

’…if we are not careful, cosmopolitan education will create citizens of the world not Englishmen. It’s Englishmen, English citizens that we want’ (1907. pg. 136)

For all its nationalistic ideas which must be viewed in relation to the time period, from Sharp’s work the musical features of English folk music are analysed and defined. Sykes however identifies many fabrications and issues with the EFSDS and their portrayed image of English folk music:

‘…the revivalists argued that there was a class of song called 'folk song' […] that this folk song was restricted to isolated rural communities, was sung by unlettered peasants and was fading with the disappearance of the last survivors of an essentially 'primitive' way of life. (Sykes, 1993. p.g 460)

Alongside the frequent uses of the words primitive and peasant, this shows the collectors’ leanings towards ideas of cultural evolution. The intentions were clearly to document and preserve rural music for use in creating nationalist art music as well as creating a greater national identity using this music in children’s schooling.

2.2 The Second English Revival

The second revival in England started in the mid 1950s after a boom in popularity of skiffle music from the United States. Folk music was performed in clubs and pubs, was mainly unaccompanied vocal music and was seen as both an alternative to the commercialised popular music of the time and as a cultural expression of the people (Keegan-Phipps & Winter, 2014.) During this revival amateur folk musicians were regarded as ‘tradition bearers’ (Keegan-Phipps & Winter, 2014. p.g. 497)

During the 1960s the English folk scene received great influence from the USA with artists like Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Paul Simon bringing with them the acoustic guitar and image of the singer songwriter. The 2006 BBC documentary Folk Britannia documents the split in terminology and repertoire at this point: artists such as the Watersons, the Spinners and Annie Briggs rejected the influences from the United States and continued to make largely vocal music regarded as traditionalist, whereas artists taking the guitar and singer songwriter aesthetics were regarded as contemporary and had overtly political left-wing material. Artists such as Ewan McCall and A.L Lloyd pushed contemporary folk music into the arena of political protest. In the documentary Shirley Collins marks this division claiming that McCall hijacked the movement for his own political aims.

By the 1970s English bands such as Steeleye Span, Fairport Convention, Lindisfarne and The Strawbs had taken the traditional music collected by Sharp et al. and recontextualised it. These groups were innovative, used electric instruments and added improvisation attracting a new audience (Britta Sweers, 2014. p.g 477) and creating Folk Rock. This new genre developed and became linked with commercial pop and progressive rock scenes. Folk Britannia highlights drug abuse, commercialisation and a lack of values leading to the movement becoming a pastiche of itself, and at the core of the English folk club-based movement was the dogma that folk songs should only be sung unaccompanied and English groups were too loud for the folk clubs, so moved into the performance spheres of prog rock (Britta Sweers, 2014. p.g 480). The English folk music scene continued, however did not see the next level of resurgence until the early 2000s.

2.3 Irish Folk Music

Irish folk music revival and collection pre-dates the English by over a century with the Irish harp festival of 1781 and the Belfast harp festival of 1792 at which Edward Bunting notated the music and created The Bunting Collection. Music collecting from this era onwards coincided with waves of Irish migration to the United States and this music lived on in the hearts and minds of those diasporic communities (Williams, 2014. p.g 605)

In 1807 the Belfast Harp Society was formed, with the Society for the Preservation and Publication of the Melodies of Ireland publishing Ancient Music in Ireland in 1855, and the Gaelic League founded in 1893 which was particularly active in promoting Irish traditional music and dance (Blaustein, 2014).

In 1896 an instrumental music competition called the Feis Coeil was founded aiming to promote all forms of Irish music within a competition style, (Williams, 2014) later shifting to music that purists might regard as traditional (Williams, 2014. p.g 607) and this was followed in 1908 with the establishment of the Piper’s Club of Dublin.

Successful examples of institutionalisation can be seen again when in the late 1930s the Irish Folklore Commission, Irish National Teachers Organisation and the Department of Education collaborated to create the School’s’ Folklore Scheme. This saw children acting as folklore collectors by interviewing family and neighbours about folklore practises, the half a million results of which were compiled in The School’s Manuscript Collection. Adding to this wealth of written resources, in 1951 the Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (Gathering of Musicians of Ireland) organisation founded the Fleadh Cheoil as an annual festival of Irish music and dance which continues to this day.

Alongside the second English folk music revival, several supergroups emerged from Ireland in the 1960s and 70s. The Chieftans, The Bothy Band and Planxy performed internationally on the world stage, inspiring a new generation to learn traditional Irish folk music. At this time, with the growth of media representation in Ireland, a session playing scene developed as part of the rapidly growing industry of cultural tourism (Williams. 2014). Irish traditional music then became part of the World Music market place in the late 1980s which increased the sales and presence of Irish music on the world stage. This was followed by bands fusing Irish traditional music with punk in the 1990s in the Irish diasporas. Groups such as Flogging Molly (Los Angeles), Dropkick Murphys (Boston), The Saints (Brisbane) and The Pogues (London) combined material on Irish cultural history with working class issues and were popular worldwide.

In summary the key elements of the development and revival of Irish traditional music are:

Written sources - dating back to 1792.

Specific Instrumental clubs and associations founded.

Traditional music lived on in the diaspora and cultural links maintained.

Music connected to cultural associations in Ireland.

The School’s Manuscript Collection - a large resource that engaged a young generation.

Fleadh Cheoil Music and Dance festival - still relevant today.

60s and 70s supergroups exported traditional music and inspired a new generation.

Cultural tourism and the rise of session culture.

Entry into the World Music market.

Popular fusion with punk in the diasporas.

2.4 Scottish Folk Music

The folk music revival history of Scotland is comparable to Irish folk music, both in style and via diasporas in North America which Richard Blaustein describes as ‘comparable developments’ (2014. p.g 559).

Folk music collecting, publishing and promoting in mainland Scotland dates back to as early as 1726 in Edinburgh with the clear organisation of piping and fiddle societies. George Emmerson states that throughout the eighteenth century an interest in Scottish national music was held by all members of social classes in Scotland, with a wave of grassroots cultural nationalism emerging in the formation of strathspey and reel societies in 1881 in Edinburgh (Blaustein, 2014. p.g. 559)

More recent developments in the revitalisation of Scottish traditional music (Blaustein, 2014. p.g. 559) have seen the invention of specialist accordion and fiddle clubs and the co-ordinating and co-organisation of the National Association of Accordion and Fiddle Clubs in Scotland. As in Ireland, Scotland has a thriving cultural tourism industry based on both historic and recently invented cultural traditions. Scottish traditional music has entered the mainstream through the World Music market under the umbrella label of ‘celtic’ however not to the same extent as in Ireland. The Scottish diaspora around Nova Scotia in Eastern Canada until recently called Scots music is now called Cape Breton music (Feintuch, 2006. p.g.11) yet still hold on to Scottish origins, and both Scottish and Irish revivals share a history of successful institutionalised initiatives.

Today Scottish traditional music can be studied at Edinburgh, St. Andrews and the Highlands & Islands Universities, as well as at the Scottish Royal Conservatoire, and lower level instrumental grades in both Scottish and Irish music are available. To compare this to England, there are currently no instrumental grades in English traditional music available, with only two long standing university courses in folk music available (Newcastle and Sheffield). Taking this into account alongside the long-standing Scottish festival scene (The Edinburgh Festival, Celtic Connections, Heb Celt Folk Festival and the Orkney Folk Festival) the extent of institutional support and opportunities for Scottish traditional music, in contrast to the absence in England, becomes clear. The exact statistics of funding received, impact of resources and local initiatives in place would be valuable to draw conclusions from and compare to England, however this is outside the scope of this study.

2.5 Celtic Identity

Throughout this study the role of identity has been ever present. In examining the progression of the English folk music revivals in comparison to those in Ireland and Scotland it is impossible to ignore the factor of identity, particularly the Gaelic and Celtic identities.

The Gaelic League was founded in 1893 as an association to promote Irish language, arts and culture through poetry, literature, and music. The invention of cultural practises such as the ceilidh satisfied revivalist cultural mores to create a strong image of Irish identity. (Williams. 2014.) Not to be confused with the Gaelic League, (and I believe building upon the success of it), the Celtic League was established in 1961 creating the self identified Celtic Nations of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, The Isle of Man, Cornwall and the French region of Brittany. Cultural, linguistic and political aims are held by this group, however the fundamental idea behind it is a shared identity. The contentious issue of the inclusion of Galicia and Asturias in northern Spain still surrounds the League, yet Peter Ellis (who was instrumental in rejecting Asturias and Galicia from the League) clearly states:

Celtic is a linguistic term; a Celt is one who speaks or was known to have spoken within modern historical times a Celtic language[…]The last time a Celtic language was recorded as being spoken in Galicia was in the 9th Century[…] I believe the focus of the Pan-Celtic movement should be on the nations where there are still living Celtic languages… (McIntyre, 2013.)

Regardless of their absence from the Celtic Nations, Mauel Alberro notes that many people in Galicia feel a Celtic identity (2008). Alberro goes on to point out that despite failing to qualify as part of the League based on the linguistic criterion this has not stopped Galicia from proclaiming a self-defined Celtic identity that has found its expression through a range of musical festivals and cultural activities (Alberro, 2008).

A BBC documentary exploring Galician Celtic identity presented by Scottish Accordionist Phil Cunningham is rife with examples and assumptions about ethnic and DNA links between Celts based upon no evidence. After the opening introduction explaining shared Celtic roots in pre Roman Europe, Cunningham says: ‘The Chieftains - the great grandfathers of Celtic music…’ and in a sentence this highlights a key issue with the Celtic identity. Throughout my research I have identified four different uses of the term Celtic:

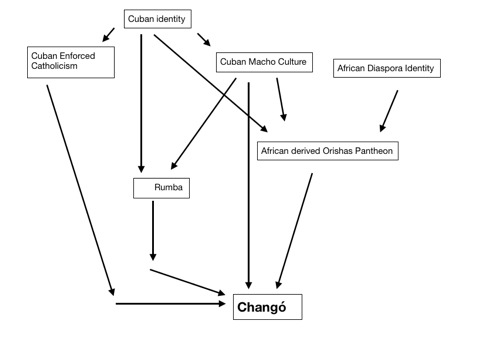

(Image 1)

The Celtic music Cunningham is referring to is in fact the traditional Irish and Scottish music from the super groups of the 70s and brought to international attention via the World Music market, marketed under the label of Celtic music. Celtic music and culture are recent inventions in comparison to the Celtic tribes of Europe and the Celtic languages that live on, in fringe areas of the Atlantic seaboard of Western Europe. Despite the modern Celtic identity being officially described as rooted in the distinct living Celtic language of each of the six nations (McIntyre, 2013.) many times the validity and authenticity of the Celtic identity is debated using the Celtic race and languages as key factors.

To explore these arguments further is beyond the scope of this study, however it is undeniable that Celtic culture in this format is a modern and successful construct (see appendix 2.1 and 2.2) The movement has a growing cohort of musicians and is an example of a highly successful folk music movement.

Bohlman highlights the dangers in nationalist music as having the potential to continue to problematise the gap between the image and reality of a nation (2003, p.g.52) however in the case of the Celtic Nations it can be seen that they transcend existing national boundaries and join countries rather than separate them. Bohlman goes on to suggest that music represents culture as both a form of expression that unites, and as a manifestation of difference (2003) with both of these extremes seen in the Celtic Nations.

The important factors to be taken away are:

1. New cultural movements between countries can be created.

2. Cultural preservation (particularly languages) can strengthen a movement’s legitimacy.

3. Historical and linguistic ties should not be allowed to dominate discourse surrounding authenticity and legitimacy.

4. Geographical and political contentions can dominate discourse and detract from the culture being created, as seen with northern Spain and the Celtic League.

Chapter 3 - Contemporary Context

3.1 Contemporary English Folk Music

In the early 2000s England entered a new phase of interest around folk music, (however not named a revival as such) with the rise of popular bands and artists; Mumford & Sons, Laura Marling and Noah & The Whale (amongst others) mixing indie rock with folk and traditional music elements to create what has been termed nu-folk. Blaustein argues that folk revivals in the Western world are historically a compensatory response to modernisation (2014. p.g. 566) and I believe that in this case it was in opposition to the rise of electronic dance music elements in pop at the time. English folk music underwent a shift in demographic as part of its recontextualisation, with a realignment closer to pop and indie rock structures (Blaustein, 2014.) and Keegan-Phipps & Winters argue how a perceived levels of authenticity came with playing acoustic instruments.

Successful English musicians such as Seth Lakeman, Kate Rusby and Jon Boden, carefully define themselves as contemporary folk and/or traditional musicians, however others closer to mainstream rock or pop genres (Frank Turner and Mumford & Sons) have a more difficult relationship with labelling. Turner is commonly referred to as a punk/folk artist (Rifkind, 2015) with an article in The Guardian stating:

‘Turner was so terrified of being saddled with the dreaded appellation "singer-songwriter" that he told everybody he was a folk singer, which "pissed off the folk purists no end” (Gittins, 2011.)

However the inclusion of folk in his labelling is only the result of his use of acoustic instruments. Mumford & Sons use instruments more widely regarded from the traditional or folk genre, yet they reject labels of being a folk band, due to negative press they received. They state that they never thought of themselves as a folk band, yet due to the acoustic instruments they play they were labelled as such in the media, then criticised in the folk scene with accusations of inauthenticity. (Lamond, 2012.)

I take the view that folk music is a continuum with traditional material at one extreme and pop or other genres at the other. Acoustic instruments have a strong impact on public perceptions of an artists position within that continuum. What is most important, as Ruth Finnan highlighted, Frank Turner demonstrates and Mumford & Sons battle critics using, is self identification. We can see this as for a time Mumford & Sons were one of the most well known music acts internationally, yet they did not identify as an English folk act to avoid criticism of their folk music authenticity. As a result the English folk scene did not share their world-wide exposure. Much like Folk-Rock in the 1970s, a new genre was created, Nu-Folk, and it was this relevant music that appealed to a young generation.

3.2 Folk Music in East Anglia

I was born in 1989 and grew up in north Norfolk with very little awareness of folk music or culture. I was raised in a rural community with little idea about the existence of English folk music other than in the loosest sense including Christmas carols and nursery rhymes. My exposure to folk music came through celtic punk music played by the diasporic bands Dropkick Murphys, Flogging Molly and The Pogues.

To study the region and it’s history I searched online and found the traditional music group rig-a-jig-jig had been active in the area until recently and some of the band members were also local historians. Band member Barbara Jane was able to give me some broad context for my questions about the region during the folk revivals, and band member and author of numerous online local history articles Chris Holderness was able to give more detail on this, and offer his opinions on the scene currently.

Email correspondence with Barbara Jane

On English folk music revival:

‘There certainly was some folk revival awareness of Norfolk.'

On folk music practises during the revivals:

‘During the 60s and onwards there were certainly folk clubs in Norwich (however) Largely not Norfolk music.’

Email correspondence with Chris Holderness

On East Anglian music history:

‘There has always been a vibrant tradition of music in East Anglia; it actually has been as strong as those of the various areas of Scotland and Ireland, but just not associated with the local nationalism of those countries, which has given it there a public impetus.’

‘…East Anglia was probably the most widely collected area for traditional music in the 1950s and 1960s, including Ireland. There are so many recordings available that show this.’

On the English folk revivals:

‘None of this has anything to do with a 'revival' and the folk club scene. It has just continued on in pubs and village halls of its own accord[…]The folk club revival scene is very different and mostly makes little reference to the true tradition of the area.’

On contemporary practises:

‘Some younger people are becoming involved, particularly with step dancing (however) It seems that most people who like 'folk' music and go to folk clubs are not, sadly, interested in the real tradition.’

The points they raise are interesting; both agree there was a vibrant music scene in East Anglia with a wealth of traditional music material collected, however this was not, and still is not the music performed in folk clubs today. The music made by the region’s numerous shanty groups was not covered by the revival movements and seems to exist in a separate genre. In the international world of shanty music these groups receive critical acclaim, perform regularly and have a contemporary online presence, however this traditional folk culture would not be instantly recognised as part of the region’s folk music. I theorise that this is a result of a national tendency to over categorise and separate genres within the English folk music scene, as I believe was the case with folk rock and other variations. Looking at the online presence of folk music in East Anglia, there is much more now than a decade ago. Ranging from historical articles to directories of live music events.

Cambridgeshire and Suffolk folk club websites - modern and accessible.

Norfolk shanty group websites - modern and accessible.

Mustrad website - difficult to access due to a very dated layout, yet contains a vast library of articles on local music and culture.

East Anglian Traditional Music Trust (EATMT) website - unfinished at the time of this study, yet starting to produce accessible content.

Mainly Norfolk - folk culture hub connecting articles to events and audio sources.

(See appendix 3.1 - 3.4 for website images)

For future development I suggest that Suffolk and Cambridge folk hub websites in the style of Mainly Norfolk should be created, with access to articles in an updated format. The EATMT could be central in connecting Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire websites together, and all sites need to take influence from the Irish traditional music website The Session (see appendix 3.3) and upload sheet music and audio files to encourage performance and further active music making, as all currently lack this.

I was able to make contact with the EATMT however they were unable to help with this study by answering my questions. Further information regarding their funding, long and short term goals, current educational initiatives and outreach methods would prove extremely valuable in this area of study, as further predictions and suggestions could be made. To add to my observations of the online presence of folk music in East Anglia I undertook primary research observations at the Cambridge Folk Festival in Cambridgeshire and the Folk East festival in Suffolk.

3.3 Field Work: Cambridge Folk Festival

Session 1

I arrive at the outdoor tent for the advertised ‘English session’ and join the circle. In my late 20s I bring the average age down significantly as most are in the 50+ category. The session has begun and the banner visible inside the tent tells me this is organised by a local folk club. A compere runs the session by pointing around the circle, indicating to each performer when to play, and by circling the tent, whispering invitations to perform at newcomers as this is an ‘open session’. I decline the offer, which is accepted as I see that there are others like me who are content just to listen.

Two elements become apparent to me: the introductions and the performance schemas.Time is given for each performer to introduce their song, this includes where the song is from and where it was learnt.

‘this song is from Devon…’

‘I learnt this song in Derbyshire from a friend of mine…’

No comments are given from the rest of the circle when location is mentioned in the introduction, yet without fail all of the singers do it. As a performance schema this is clearly a moment to indirectly highlight the appropriateness of the material, and I wonder if by pointing out the oral tradition it influences perceptions of authenticity. Highlighting the deliberate use of regional accents once again demonstrates an awareness of appropriate performance style, in this case to create certain rhymes:

‘I’ll have to sing this northern otherwise the words wont work properly, so apologies to anyone from Derby here…’

It could also be the case that the performance schema of a dedicated introduction section functions to check the repertoire of the session adheres to the title of ‘English’.

It is clear that there is some sort of cannon of repertoire so I ask my neighbours on either side of me where these songs are learnt - they reply that they are learnt from sessions like this.

Session 2.

I return to the same tent for an ‘open session’ run by another local folk club with a different compere and here I notice different schema for whole group inclusion. The majority of songs have a repeated refrain or chorus section which is explained before starting. We are encouraged to sing this part and the whole circle complies with improvised harmonies with minimal explanation. A line is sung once then the song begins and with a hand gesture we are invited to sing.

Lyrics are given equal importance to musical skill as some songs are short but receive applause and praise for the quality of the singer, whereas others are long story songs which receive a great level of interaction during the performance through applause and laughter, regardless of the singers vocal abilities.

I talk to stewards and festival attendees during the festival and note the difficulty in defining folk music, the importance given to acoustic instruments and stating geographical places. I conclude that both using acoustic instruments and recounting song histories with reference to places must contribute to a perceived level of authenticity from the crowd, often described as ‘being genuine’.

I wonder if this feeling of a ‘genuine’ performer is instilled subconsciously through performance connected to a sense of transparency which the audience respect in comparison to pop musicians.

Conclusions:

1. English sessions focus on songs.

2. Songs include audience participation.

3. Repertoire is learnt through attendance at sessions.

4. Schemas of performance are present.

5. Song history is important in validating authenticity.

6. Spoken accents are used and highlighted for authenticity.

7. The accepted idea of folk music as more genuine than other genres.

8. Majority of participants are in the 50+ age bracket.

3.4 Field Work: Folk East Festival

Session 1:

I sit at the back of the tent as a nearby table plays Irish tunes - Northumbrian pipes, tenor recorder, whistle, guitar, two fiddles and a bodhran. The performing schema are consistent with my observations of Irish sessions at the Cambridge Folk Festival; the music is instrumental, pentatonic, and the tunes are linked together by an unspoken leader. A fiddle player starts a tune and leans to their left and right to welcome the rest of the circle to play. They carry the tune through a series of nods, raising and lowering their body to signal dynamic suggestions and using eye contact cues when sections change or repeat.

After circling around the material a number of times in different combinations of melody and accompaniment the volume starts to drop. A concertina player lifts their instrument off their lap and begins pumping out a new string of notes which is eagerly joined by the bodhran and guitar. With the rhythm section backing the concertina drives on with the tune, changing to a second section as the other instruments start to follow. With the new tune a new leader has been unspokenly selected and with a falsetto whoop the session seems to all fall in behind them. There are no introductions to the tunes, and no discussions of arrangement. Players who are visibly unfamiliar with the tune sit on the fringes with a head cocked to one side, working out a part at low volume. The session is not explicitly labelled as Irish, however I recognise some tunes and the general style as such. I notice that from the initial core of players, numerous people come and go without appearing to know the repertoire. They work out a part and play a more visible role once they are confident it fits.

Session 2.

I return to the pub tent and observe an informal session where the music sounds like Morris dancing music. A melodeon and concertina dominate, the expanding and contracting of their squeezeboxes establishing dotted quaver melodies in 4/4 time. The tunes lurch with an accented emphasis on the first and third beat of the bar with the heavy pushing and drawing of air into the bellows of the instruments. The musicians sit with eyes closed lost in the melodic whirl of the jig. Others holding instruments sit near but do not join them unless they are clearly familiar with the tune. I can clearly note that the melodies are very long making them harder to follow than the Irish tunes.

Session 3.

A large crowd has gathered for this more formal session. The instrumentation is dominated by melodions and concertinas and I estimate that of the 20 or so musicians, only two are in their early 20s and the majority of the others are in their mid 50s or above. Songs are introduced by a soloist who explains the song history and any audience response parts. We sing along to a free refrain in a drinking song, then the whole tent is lead in a rendition of the shanty ‘Bound for south Australia’ to thunderous applause. Many instrumental tunes follow and I see that again the music is stylistically similar to music accompanying the Morris sides. As in the Irish sessions, these tunes are not introduced and are lead by the performer who starts them, however those in the circle who do not know the repertoire do not quietly work through it - instead they sit out and only play the tunes they know.

Folk Club Session

This performance slot is organised by a Suffolk folk club and the organiser gives a brief speech about the club history then lists the performing acts. The first musician plays for an hour on the acoustic guitar and none of the material is in the folk genre. She introduces each track and despite being acoustic covers of pop songs, is received well by the audience and the organisers. This leads me to re-evaluate the question of what is folk music? To my definition the only musical feature that is present is an acoustic instrument, but this is enough for the crowd and the organisers.

Conclusions:

Irish and English instrumental sessions share schemas of performance in some areas.

2. Irish tunes are more accessible than English - possibly due to the use of the pentatonic scale.

3. English tunes have more notes, are more scalic and have less rhythmic variation than Irish tunes.

4. The general public equate Folk music with acoustic instruments.

5. The history of the music is held in high regarded and given designated time before performances.

6. Shanty music is popular, possibly because the pentatonic melodic character allow for easy participation.

Chapter 4 - Revival

4.1 Reasons for Revivals

Drawing upon the work of Ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl, Blaustein sights folk music revivals as an attempt to offset disorientation and displacement by an alienated middle class, by allowing them to periodically regenerate and identify with an idealised and romanticised idea of rural or folk communities. Looking at the numerous folk music revivals in England, Ireland and Scotland this can be argued to different degrees, however the reasoning behind such revivals is not the concern of this study. My interest lies in understanding what happened and creating a coherent narrative explaining the different musical landscapes we see today. My own interest in increasing folk music making comes from a belief in the numerous positive social and community benefits music making can initiate and support. The ability of music as a vehicle for social change is echoed by Tamara Livingston who says: ‘Music serves as a powerful means for restoring and reengaging individuals with each other, their culture, and their past’ (Livingston, 2014. pg. 68/69)

The case study examples I use focus on the practical features of revival efforts, rather than the reasons behind their inception. The concept and terminology of revival must be explored as, like folk music, there are many different uses and examples which overlap.

4.2 Use of the Term Revival

Mark Slobin suggests that the term revival should be abandoned as it is outdated. In Livingston’s revisited paper on the subject in 2014 she highlights the problems of the term, giving the example of the participatory continuum in which once a revival effort experiences a certain degree of interaction and participation then it becomes an act of social-musical interaction in its own right and arguably ceases to be a revival (Livingston, 2014. p.g. 64) Hill and Bithell put forward the remedy that the term revival is broad and contains the varied integrated processes of Regeneration, Reclamation, Resurgence and Recreation. As these terms share the fundamental motivation of drawing on the past to intensify some aspect of the present, and by accepting this definition, it allows us to see revivals as groups of related movements (Livingston, 2014. p.g 63) To this list I add the term reinvention as I believe it to be a key concept in revitalising musical scenes.

4.3 - Recontextualisation and Authenticity

Recontextualisation happens with every musical performance and needs to be openly acknowledged within folk music circles, as too often contemporary contextualisations are dismissed as inauthentic, while it is also acknowledged that any artistic culture must continue to develop otherwise it dies. Authenticity is another fundamental feature with definitions given by Owe Ronström in 2014, focussing on the attachment of factuality, truth and effect to a musical practise. Ronström recognises the links to legitimation and emotional response and suggests three positions from which authenticity is validated:

1. Doers - (making music) - quality and authenticity are anchored in music making and the experiences that evolve from it.

2. Knowers - (knowing what the music is about) -authenticity is found in managing the knowledge.

3. Marketers - (distributing) - the goals of the Doers and Knowers result in the marketers goals being met.

Ronström argues that all revivals are examples of decontextualisation and transvaluation of the obsolete or old-fashioned to create something new (Ronström. 2014.) and in accepting this as an inevitable process I believe there can be more focus on the relevancy of the work itself and how it connects to the next generation of participants. It is with this lense that I view case studies and try to extract successful elements that could be used to expand the East Anglian folk music scene.

4.4 Folk Music Revival Case Studies

Case study 1: (for full case studies see appendix 4)

In Folk Music Education: Initiatives in Finland, Tina Ramnarine explores the national initiatives conducted in Finland to create a thriving national folk music scene. Ramnarine highlights a rise in popularity of Finnish folk music as a result of:

New definitions and interpretations of folk music.

Implementation of folk music education on a national level.

Innovative contemporary groups popular for creating new folk music rooted in tradition.

Institutional structures.

Revival of national instruments.

In Innovation and Cultural Activism Through the Reimagined Pasts of Finnish Music Revival Juniper Hill also tackles the topic and through analysing the revival and its connection to an imagined past. Hill provides some broad concepts to take away:

1. Reimagining the past has been a successful way to create cultural change, and to inspire and legitimise innovation… (Hill, 2014. pg. 413)

2. Borrowing elements from the past is always selective - thus revivals always include recontextualisation (Hill, 2014. pg. 394)

3. Revivals almost always end up[…]creating something new (Hill, 2014. pg. 393)

Case study 2:

Jan Ling’s paper Folk Music Revival in Sweden: The Lilla Edet Fiddle Club documents the recent rise of fiddle and nyckelharpa clubs in Sweden. In this case study the following key elements for success can be seen:

Mass media support

National funding for adult recreational activities

Clubs and music schools established

Adapted regional traditional material to create a new core repertoire

Case study 3:

Colin Quigley studied the rise and development of the Hungarian Dance House movement and the revival of Transylvanian string band music from which some interesting insights can be learned. Three elements can be attributed to the success of the movement:

Institutionally funded celebrations, competitions and festivals

Authenticity validated through the inclusion of the keepers of tradition

Relevancy for the next generation through organised youth social dances

For all the successes of relevantly recontextualising cultural practises for a new generation, the movement experienced problems:

Geo-political labelling of the repertoire as Hungarian, Romanian or Gipsy lead to imagined divisions and a descent into ethnic and nationalist debate.

Funding from nation institutions held influence over the revival and these institutions had other nationalist agendas.

Recontextualising material in national institutions, and an over reliance upon them contributed to a loss of musical functionality in its original form.

Conflicts arose among revivalists, academics and traditional culture sources.

It is suggested that the movement survived despite these issues largely through the sustained commitments from the core participants (Quigley, 2014) From these case studies I make the following conclusions regarding folk music revival movements:

1. Institutional Support - crucial, yet over-reliance must be avoided.

2. Innovation Focus - leads to the creation of new, relevant material.

3. Authenticity - the source must be carefully considered and flexible.

4. Recontextualisation - inevitable and must be acknowledged.

5. Preservation and Innovation - can exist together.

6. Relevancy - keeps traditions alive.

7. Partnership - shared identities and goals with other art forms gives support.

8. Nationalism - can dominate debates and funding.

9. Musical Education - targeted at the next generation creates continuation.

10. Revival of Instruments - can instil identity to new compositions.

11. Individuals - invaluable, from tradition bearers to educators.

12. Revival - true revivals always lead to something new.

13. Reimagining the Past - inspires and legitimises innovation which can positively effect local culture and economies.

Chapter 5 - Conclusions.

5.1 - Research Question 1

Q1. Why is folk music in England received and experienced so differently to folk music in Scotland and Ireland?

I have studied the history of the numerous revival movements in each of the nations and present the following summary table to distill the information down into relevant elements:

Revival summary table:

From these events I now present a table of what I see as the generalised significant differences between the movements that account for differences in their current states:

What can we take from this?

The areas of identity and connecting with other traditional cultural practises show striking differences in how the revival movements were managed between the countries. The aims, sources collected, and educational strategies also show key differences and I believe that these are the broad reasons for the differences in traditional/folk music and culture between the countries today.

5.2 Research Question 2

Q2. What is the folk music scene in East Anglia like at present?

This question involved field observations at folk festivals in Cambridgeshire and Suffolk, correspondence with Norfolk musicians and local historians, and analysing the current web presence of folk music in the region online. I conclude that currently:

1. Extensive musical and historical resources exist online, yet the majority are difficult to access.

2. Some recent online hubs have been created.

3. Folk clubs play varying degrees of folk music. Other genres played on acoustic instruments are accepted.

4. Sea shanties are popular and accessible, yet not widely regarded within the folk/trad. genre.

5. The music festival scene is well attended.

6. Irish sessions are popular and musically accessible.

7. Older generations dominate music and dance practises

8. Sessions contain multiple performance schema and are defined by nationality of repertoire.

9. Authenticity is not uniformly measured and can dominate discourse.

What does this mean for the area?

Growing up in the area I see a general lack of coherent regional identity. From studying how regional, national and Celtic identities are tied to music in Ireland and Scotland, I believe that building on the folk music practises that currently exist in East Anglia could contribute enormously to creating a modern regional identity. Nicholas Cook also argues that music is both a reflector and generator of social meaning, and as such, music can become a resource for understanding society (2013. p.g. 213) I agree with this and believe that with this in mind, it would not only help create an identity but could also have a positive effect on wider community issues in the region.

5.3 Research Question 3

Q3. What are musical revivals and how do they work?

This area is crucial in understanding not only what a revival contains and why it happens for the purposes of studying the UK folk music revivals in the past, but also for creating a framework for how East Anglia could develop its folk culture in the future. Two conceptual areas in the revival field answer my third research question:

1. Mark Slobin - The term revival really means many things:

Regeneration

Reclamation

Resurgence

Recreation

2. Caroline Bithell, (2014) Processes that take place in musical revivals:

-Activism/desire for change.

-Validation/reinterpretation of history.

-Recontextualisation and transformation.

-Legitimacy and authenticity.

-Transmission and dissemination.

-Post-revival outgrowths and ramifications.

5.4 Research Question 4

Q4. Theoretically, how could folk music be revived in East Anglia?

Studying the history of UK revivals, learning from wider revival case studies and making primary observations and analysis of music made in the region today, I arrive at a position from where I can make suggestions regarding future initiatives, yet I am aware that the conclusions I make are recontextualised here. I do not suggest that successful initiatives from other revivals will be instantly successful in East Anglia, however these are simply suggestions and I hope that at the very least they will provide points from which further research can pick up from, eventually leading to the implication of further informed musical revival initiatives in the area.

General aims:

The music should not be regarded as revived but as reinvented, as it would build upon music gathered and instruments played in the past.

A clear and flexible definition of what folk music is.

Open acceptance of the recontextualisation that comes with playing traditional material.

Clear definition of what constitutes authenticity.

Focus on being contemporary and relevant through innovative practises.

Drive to create new music whilst not forgetting the old.

Avoid the trappings of over categorisation seen in the past in English folk music through flexibility in accepting musical and stylistic variations.

Promote the reconceptualisation of creativity as Jason Toynbee argues, as a standard cultural process rather than a heroic act made by an extraordinary personality (203. p.g. 111) thus maximising engagement and innovation from all persons.

Self define the scene using John Shepherd’s definition of a musical scene as a cultural space with much cross-fertilisation from outside influences, in which a range of related musical practises exist. (Shepherd, 2003)

Link with other cultural movements through reinvention or invention of instrumental and dance traditions.

Collaborate and connect with other regional dance and arts movements.

My suggestions for specific initiates:

1. Institutionalisation

1. Folk music education modelled on the Finish system. Learn both traditional material and promote developing it. Fund teachers and provide revived instruments.

2. Create instrument clubs to promote specific musical practises.

3. Update online history and music resources with a central hub for each county connecting multiple smaller sites. Model musical resources on Irish traditional music website The Session.

4. Collect, reformat and publish collected music from the region gathered during the first folk music revival.

2. Music

Create new music mixing the stylistic features of English folk music established by Cecil Sharp with contemporary features.

Promote and support regional artists through competitions, small tours and financially and logistically support recording sessions.

Fund instrument, songwriting and performing workshops by professional folk artists.

Collaborate with regional folk dance groups in creating new material and performance.

Link practises with other folk scenes of similar musical aesthetic (Celtic, Gaelic, Scandinavian, regional English) to widen exposure, learn from them and increase creative cross pollination.

Continue to promote the revival of the East Anglian dulcimer and melodeon.

Continue to promote regional step dancing.

Invent the tradition of other East Anglian instrument playing (such as fiddle, bag pipe, pipe and tabour and whistle for example) as these are strong cultural symbols of folk music and have global networks, institutions and resources that could be connected to.

Similarly, looking at the popularity, accessibility and global appeal of the ceilidh, a regional variation could be invented and promoted.

3. Organisation/funding

Strive to create regional cultural tourism based on musical practise. Look at Ireland and Scotland as models. Build upon the regions’ established rural hospitality industry.

Investigate funding for financial support of regional traditional practises such as the dulcimer, melodeon and step/clog dancing.

Establish clear regional centres physically and online, with the same aims.

Seasonal programs with regular and accessible events for both the older generation and the younger.

Build upon existing online resources, overhauling online libraries to make their content more accessible.

Continue to promote and participate in the growing festival market, collaborating with other regional art forms.