Geordie living in Walthamstow, East London. Socialist and vegetarian. Writing about left-wing politics, supernatural fiction, Modernist design, the uncanny and where all of these meet.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

A Warning To The Carless: Why Labour must invest in rural rail

As the autumn months approach, I relish any opportunity to dig out my copy of the Collected Works of M.R James, Britain’s greatest writer of ghost stories. This year, I said to myself, I will go one step further than just reading his stories, and make the pilgrimage to Suffolk to see where his inspiration came from. I picked out the seaside town of Aldeburgh, where one of his most famous stories, the bleak and unforgiving ‘A Warning to the Curious’, is set. Written in 1925, the protagonist Paxton traverses the Suffolk coastal area by train with ease.

But the more planning I undertook of my proposed trip, the more I realised that the route described by James no longer exists. Trains will only take me within 8 miles of Aldeburgh, and then I would have to engage with a concept that strikes fear into any British person’s heart more than any ghost story: the rail replacement bus.

This whole affair got me thinking about how we have allowed this situation to come to pass.

The current political landscape is fertile ground for the rethinking of old political orthodoxies, yet little has been said about the Devil’s Pact subsequent British governments have made with the motorway lobby since the 1960s. It was Macmillan’s Conservative government that commissioned the Beeching report, and subsequent Labour governments adherence to its principles, that has created a distorted transport landscape in favour of cars and to the detriment of rural rail. Beeching’s report proposed demonic cuts to rural railway services deemed unprofitable, and recommended the closure of 55% of railway stations in 1963. Little account was taken for the economic turmoil that would face communities being sent to the gallows. Nor was it considered that lines deemed unprofitable may not always be so in the future. Local passenger campaigns managed to save several key lines, but many were laid to rest.

To give Beeching his due, to mitigate the wide-ranging retrenchments, he proposed a massive investment in rural bus services, that both Tory and Labour governments failed to deliver on. Starvation of local bus services under austerity now sees Britain with the lowest level of bus coverage since the late 1980s.

The throttling of both rural rail and local bus services is a perfect storm for many rural and seaside communities, leaving them isolated and utterly dependent on cars. Many of the stations that were closed in the 1960s lie in waste and ruin, sacrifices on a premature funeral pyre in the name of ‘efficiency’. A great number of our nation’s seaside towns, those that have not yet been able to repackage themselves as ‘the new Brighton’, have often been dubbed ghost towns by the press. Ironically for M.R James, the only ghosts that haunt the Suffolk coastal towns he loved so much are those of a well-connected past.

If this desiccation of our rural connectivity it is to be reversed, it needs a radical investment and bold vision to move past Beeching and restore some equilibrium to the country’s transport infrastructure. There are several important reasons why Labour must take this up:

1) Labour’s pitch to rural voters. Committing to reopening local railway services would show rural and seaside voters, traditionally Conservative voters, that Labour has an exciting and relevant offer that directly impacts on their communities and that Labour understands the economic landscape they face. It would firmly place Labour tanks on Tory lawns, where campaigns to save rural bus services and encourage inwards investment are often big mobilisers in rural and seaside Tory seats. Analysis by the Social Market Foundation (SMF) thinktank found that in 85% of Britain’s 98 coastal local authorities, people earned below the national average for 2016, with employees in seaside communities paid about £3,600 less. Yet in seaside constituencies like Waveney in Suffolk, Labour’s vote receded in 2017, rather than advanced. Nothing in the demographics of those who live in seaside towns are beyond Labour’s reach: addressing them with an offer that reverses 50 years of transport neglect is crucial.

2) A greener and more equal infrastructure portfolio. Labour could put an end the tilted transport landscape that currently favours of cars, encouraging rail usage and benefiting the environment with reduced carbon emissions. Unlike other parts of the economy, where significant progress has been made to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, road transport emissions have actually increased by 1% since 1990. By contrast, the total greenhouse gas emissions from rail (including both freight and passengers combined) are an order of magnitude lower at less than 2% of total UK transport emissions

3) Young people are being costed out of road travel. Car insurance has increased by 80% for young people in the past two years, for example, compared with a 20% rise for those aged 50, while numbers of those aged 17-19 who take the driving test have dropped by a fifth in the past five years. Travel by car is becoming a luxury for many, and closing horizons, and job prospects, as a result.

4) Re-opening our country for exploration. Reviving the rural rail network would rejuvenate large parts of the country for rediscovery, leading to new markets and increased tourism. Reestablishing good quality local rail services would lead to trickle-up economic renewal in a lot of previously isolated communities. A fundamental level, having our country closed to many people is wrong. Trains are our gateways to discovery; to accessing and feeling a sense of ownership over the country we live in and beyond; to maintaining contact with family and friends, regardless of where you live; to exploring villages and towns you have only read about, making that spur-of-the-moment trip to visit somewhere because you like the sound of it. Despite what Theresa May says, our country is closed, not open. Labour need to open it.

Labour have an opportunity to correct a historic injustice, and build a railway network that serves the people and communities, not big cities or the motorways. If Labour is to exorcise the ghost of Beeching, it must be bold in its approach. The rewards are there to be reaped.

Written by Calum Sherwood. Follow me on Twitter at: @CalumSPlath

0 notes

Photo

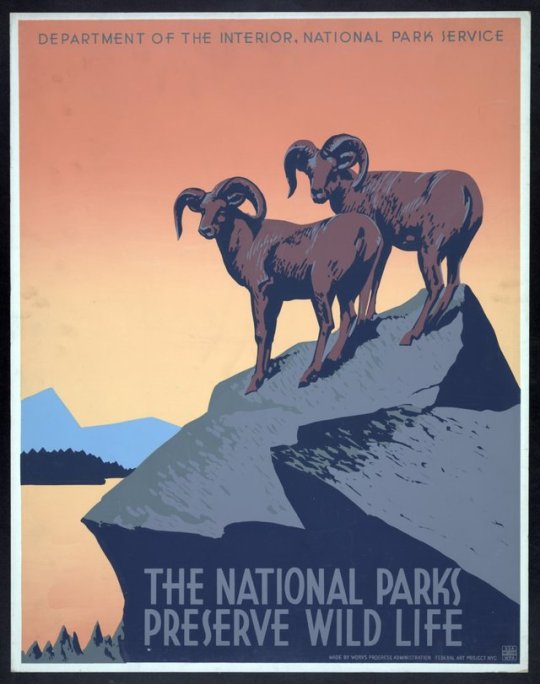

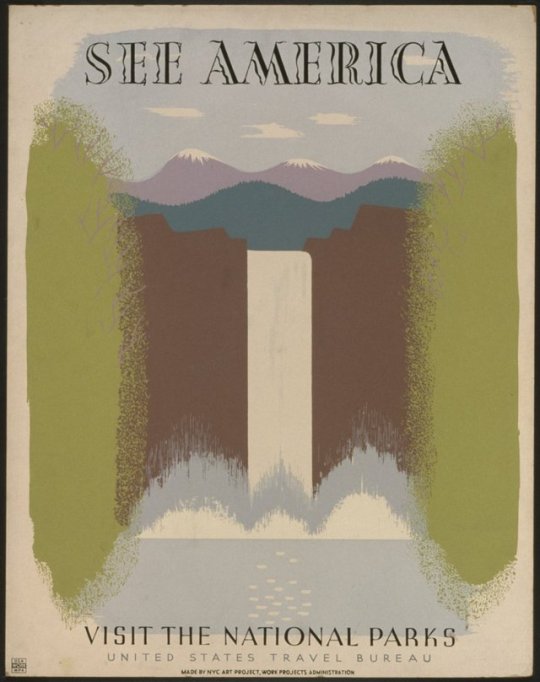

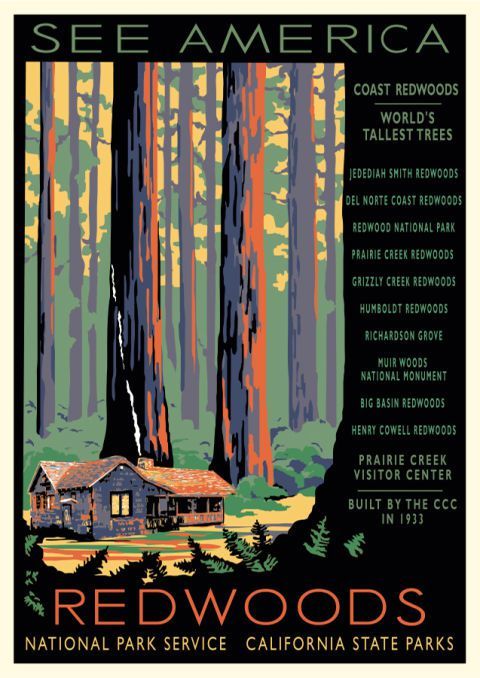

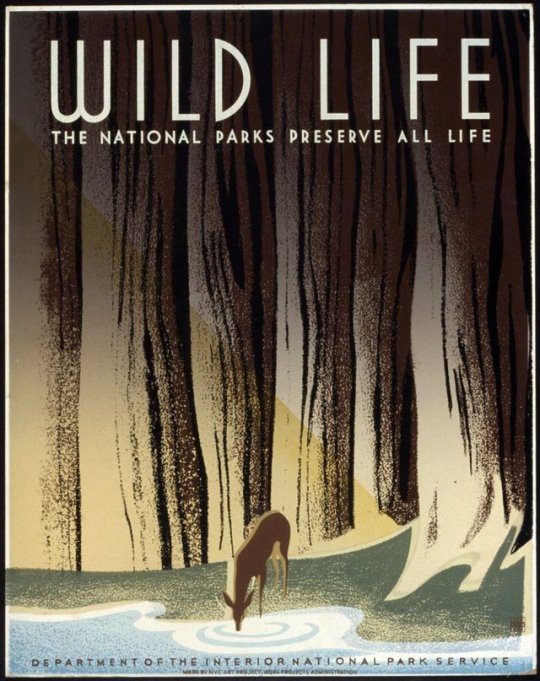

Hauntology of 1930s National Park posters: ghosts of state-funded design.

0 notes

Text

The North East: A cultural titan waiting to be unleashed

I have been thinking a lot about why the North East is never really given the same credit culturally as other Northern areas like Yorkshire or cities like Manchester. Although the North as a whole is underrepresented in a lot of conversations about our national story, the North East in particular feels strangely absent.

The North East's history is unique and beautiful, defined by its surprisingly untouched and almost mystical landscape. The dense and isolated Kielder Forest of Northumberland divides England from Scotland, and Holy Island, the birthplace of Christianity in England, has to be seen to be believed.

Historically, the North East was the centre of medieval learning, where the Kingdom of Northumbria was the richest and most scholarly of the Kingdoms of England. It is where the first history of Britain was written by a Briton. Our dialect is a fusion of Scandinavian and Old English. The North East is home to England's first stained glass windows and the world's first animal protection laws at Lindisfarne. Our people are diffident and proudly independent, always insistent we are the 'true North', distinct from Liverpool, Leeds and Manchester. Our folk songs share more in common with Scotland and Norway than the rest of the North, sharing many common words and stories.

From the Pitmen Painters to the brass bands of Durham Miners’ Gala, and the lyrical speeches of “Red” Ellen Wilkinson who led the Jarrow March, the art of the North East is inflected with its politics of solidarity and defiance.

I'm reminded of the words of the playwright J.B Priestly, written when he was touring England, that so much of North East culture is indebted to and led by a strong working-class:

"In Gateshead, we passed some little streets named after the poets, Chaucer and Spenser and Tennyson Streets; and I wondered if any poets were growing up in those streets. We could do with one from such streets; not one of our frigid complicated sniggering rhymers, but a lad with such a flame in his heart and mouth that at last he could set the Tyne on fire."

Gateshead has never been recognised with a Poet Laureateship, but it need look no farther for candidates than Alex Glasgow, who gave the world “The Socialist ABC”, one of the greatest and most humorous left-wing folk songs ever written.

Socialist politics, a strong sense of community and our isolation from the rest of England have melded to create an idiosyncratic and unique culture of our own.

I hope the Great Exhibition of the North, starting this month, can finally put an end to our cultural 'inferiority complex', and we can show the world why the North East has so much to be proud of. While the project began as a piece of Tory triangulation to pretend they had an interest in the cultural life of the North, I hope that in resistance to these cynical beginnings, it can flourish into something that truly shows the North East at its finest.

Written by Calum Sherwood. Follow me on Twitter at: @CalumSPlath

1 note

·

View note

Text

Capitalism: a Gothic horror story

Capitalism has been the longest horror story ever told; indeed, it is the longest Gothic horror story ever told. The Gothic writing tradition is steeped in the horrific details of capitalism: technological innovation leading to unnatural disruptions in society (Shelley), greed and avarice leading to hauntings at Christmas (Dickens), forgotten curses unearthed through academic curiosity (James). Capitalism’s monstrous qualities are pure Gothic - and Victorian capitalism’s greatest critic was Karl Marx. Yet rarely is he associated with the wider Gothic canon, and the Gothic’s concern with the dehumanising impact of capitalism.

Dracula can be seen as a zenith of a Gothic horror tradition that had been developing over the course of the 19th century, catching the popular psyche of Victorian society like no other work, scandalising and intriguing it in equal measure. Dracula laid bare the Victorians’ most salient but repressed fears about the modernising effects of capitalism: the changing role of women in society, the impact of migration (internally and from abroad) as communities respond to nascent international markets, and the perceived moral depravity that rising poverty incubates. Dracula was Gothic horror as political treatise, and as society’s mirror.

Yet those same fears which Stoker drew upon in writing Dracula were first laid bare, with surgeon’s precision, in the earlier works of Marx. Karl Marx published his dissection of the state of the modern Victorian economy, Capital, only thirty years before Bram Stoker’s Dracula was unleashed to the world, and although there is no documented evidence that Stoker had read the sociologist’s work, Marx contributed to a moral and political tone that resonated throughout Gothic literature.

If Dracula was Gothic horror as political treatise, Marx’s work was its inversion. Marx draws heavily on the febrile tropes of the Gothic’s fascination with the uncertain, the mystical and uncanny, to articulate a political vision steeped in Gothic horror. Victorian society was witnessing massive social upheaval, as ever-more rural workers were forced into the growing towns and cities, to work the factories and mills in appalling conditions. Slaves to the clock, the shift and to their factory owners’ whim, Marx describes the new working-class like hordes of zombies, deprived of their free will and their freedom, ready to cannibalise the class which has fed from their labour for so long.

In a beautiful line from The Communist Manifesto, published 30 years after Frankenstein, Marx writes:

“Not only has the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons — the modern working class — the proletarians.”

To Marx, capitalism has created its own Frankenstein’s monster: a beast who has been deprived of its freedom and dignity for so long, it will fatalistically rise up and wreak havoc like in Mary Shelley’s classic novel. In Frankenstein, the monster lashes out at the maker who has summoned it forth and given it life, with no respect to the monster’s material conditions or what kind of life that may be. Marx compares capitalism to “the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up with his spells”, the inference being that the unnatural power capitalism has brought into the world will eventually destroy it. Elsewhere in the Manifesto, Marx draws upon the Gothic imagery of the cemetery to articulate the same idea:

“What the bourgeoisie therefore produces above all, are its own gravediggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable.”

Marx’s most prescient articulation of Gothic horror foreshadows Dracula in his frequent comparisons of the exploitative nature of capitalism to a vampire. Capitalism drains the blood and life-force of its workers in order to enrich a class of society whose contribution is ‘undead’, absent and yet ever-present. Marx claims “capital is dead labour which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks”.

The erosion of the natural day, governed for centuries by the availability of light from the sun, appears in Marx’s writing as a sort of vampiric curse. The working day as a social construct was elongated by the Industrial Revolution with the introduction of gas lighting (and later electricity), meaning that factory workers could toil from early in the morning to past midnight. Capitalism had found a spell in which to turn nights into days, and for the reach of the ‘undead’ bourgeoisie to stretch further into the lives of the working class.

Indeed, Marx wrote of this phenomenon:

“The time during which the labourer works is the time during which the capitalist consumes the labour-power he has purchased of him. The prolongation of the working day beyond the limits of the natural day into the night only slightly quenches the vampire thirst for the living blood of labour.”

Conceiving of Marx’s work as part of the Gothic canon is important for several reasons. It credits Marx’s writing as not only eviscerating and insightful, but also beautiful and haunting. Much has been written on the haunting nature of Marx’s work, from Derrida to Miéville, who do it far more justice than I can. However, it is important to situate his work as a significant literary contribution to Victorian writing, as it empowers the understanding of the horror genre as both psychical and political.

More importantly, the Gothic is experiencing a renewed relevance in the late 2010s, as we broach the cusp of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Across politics and culture, we are retreating as much as revolutionising, and old modes of political praxis are finding new resonance as we navigate uncharted and unstable times.

Gothic writing is filled with stories of haunted and decaying landscapes, where those wronged in past continue to admonish an unheeding present. The Castle of Otranto, the isolated setting of Walpole’s Gothic masterpiece, is the archetypal haunted castle: decrepit corridors; infernal dungeons hidden below lofty audience chambers; secret passageways designed for lovers and then forgotten.

In Britain, the crumbling state of our national infrastructure is our Castle of Otranto, an ill-fared sepulchre from the past, its potential fading from the memories of even the generation who once built it. Railways left unelectrified, starved of investment. Prisons administrated by faceless companies, profiting from misery and social decay. Mould-filled private tenancies, infected with late capitalism’s insatiable lust for ever-depleting blood.

Empty castles are now empty apartments, haunted by the spectres of off-shore investors. Indeed, what could be more Gothic than a landscape of hundreds of unoccupied luxury homes, while Grenfell Tower burns?

Gothic writing is filled with ghouls hiding behind respectability and titles, seeking to provide credibility to monstrous desires. In Bram Stoker’s novel, Count Dracula positions himself as an aristocrat with a desire to own property in England, masking his lust for human blood through the apparently more benign practice of property speculation. Even when warned by the local population to stay away from Dracula’s Castle, and then confronted with the Count’s monstrous appearance in person, Jonathan Harker (Dracula’s English estate agent) continues to trust in the Count’s business motives until it is almost too late.

Harker’s distrust is suspended by his own self-interest in the Count’s commercial ventures, compounded by the veneer Dracula’s aristocratic office affords him. We are living in a time of false grandeur and undue deference in politics, to an almost equal measure as we are witness to rising resentment towards such unearned power.

And Gothic writing is filled with repressions, long-held and bubbling, finally bursting forth with profound effects. In some instances, the lifting of these repressions is emancipatory: forbidden desire turning into love; boundaries of class and status withering away to reveal a common humanity. In other instances, these repressions have been left too long, and they are most horrifying in effect. The political moment we are living through grappling with repression. Channeling, and refining, what bursts forth into a better and more progressive agent than that which previously chained down the beast is a task we all must play the role of steward to.

Finding and understanding the cultural centrality of Gothic horror throughout the First and Second Industrial Revolutions shows a method in which to analyse anxieties and fears during rapid change, and attempt to predict how those fears may be made manifest, politically and socially. Reading Marx as part of that tradition is critical to this undertaking, if we are to make sense of the longest horror story modern society has been told.

Written by Calum Sherwood. Follow me on Twitter at: @CalumSPlath

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The biggest Brute: the North East’s concrete utopia

After reading Karl Whitney’s excellent account of the significance of Newcastle-upon-Tyne’s disappearing Brutalist architecture, I was inspired to reflect on the impact those concrete landscapes had on my formative years growing up in the North East in the 1990s.

I was always fascinated by the Brutalist buildings around me; they felt like they lived and breathed the memory of an industrial heyday which was fast disappearing by the time I was alive. The North East of my childhood was witness to the first glimmer of investment under New Labour, and regeneration projects such as the Millennium Bridge and the Sage Gateshead cultural centre articulated a vision of cosmopolitan postmodernism: impressive, but alien; a mesh of influences far removed from the organic landscape of the North East.

I cherished the Brutalist architecture I came across, even as they were persecuted by my family as ‘eyesores’, including by my Mam from whom I had acquired my taste in so many things. The more I was told they were ugly or hideous, I found something in them compelling - they were bold and purposeful, even if faded, and seemed to belong to a different projection of where the future belonged, in stark contrast to the regeneration efforts on the Gateshead Quayside.

Brutalist public buildings such as Sunderland Civic Centre, with its hexagonal design which centred the public-facing service desk, embodied ideas of community, and local government for and owned by the people. Brutalist housing estates, such as Gateshead’s Chandless Estate, appeared designed with the intention of keeping people together, rather than seperating them, and enmeshing people into each other’s lives. As an only child for 10 years, whose family was dispersed across the North East, the idea of having whole communities (families, shops, social spaces - even a pub!) in one complex seemed massively appealing.

My Mam told me that Brutalist buildings looked haggard as soon as they were built, but that didn’t convince me. Even if the execution had been less than perfect, the ideas they represented didn’t seem to me discredited. Different buildings play-out in my memories like background music to my early years; The Dunston Rocket, a concrete necropolis imposing itself on the skyline, I would see from my car window on the way to the Metro Centre. Trinity Square Carpark, which I’d look up at in awe, like a monstrous spacecraft that had crashed onto Gateshead high street. The once-infamous Byker Wall, perhaps Newcastle’s most iconic Brutalist build, which I would always insist on diverting our route in order to drive past whenever we were in that part of town.

As I got older, I began reading more about the North East’s Brutalist heritage and the political ramifications of these buildings. In the North East, the name T. Dan Smith is inseparable from the word ‘Brutalism’. Smith was the Leader of Newcastle City Council from 1960 to 1965; he was nicknamed “the Mouth of the Tyne” during his time in office for his populist and outspoken persona - he was something of a hybrid of Ken Livingstone and Brian Clough, a bombastic figure who inspires and divides in equal measure. His career ended in disgrace, having fallen foul of the greed and vanity that all too many socialists pretend to have surpassed. But he had a passion and a vision for the transformative capacity of local government. Smith in particular recognised what imaginative and bold public architecture could achieve. It could liberate, it could educate, and it could change life chances. It was these qualities which made him a personal hero of mine.

Brutalism was derided at the time of its inception as a school of public architecture which preferred to dismantle and replace with concrete, rather than preserve. These arguments may have held true in some senses: the Killingworth Towers in North Tyneside was a major house building project which was demolished after only fifteen years of existence. The enthusiasm for Brutalism by public planners in Gateshead, the area I grew up in, resulted in many old Victorian and Edwardian buildings, tarred by coal and smoke, being pulled down rather than renovated. This soured the public’s attitude towards Brutalism.

But it is ironic therefore that the same logic is repeating itself: planners' desperation to pull down Brutalist buildings is destroying a key part of our heritage. The Dunston Rocket (officially called The Derwent Tower) and Gateshead’s Trinity Square Carpark are both no more, despite vigorous campaigns to preserve them (including the intervention of Sylvester Stallone in the preservation campaign of the latter). Other Brutalist building, like the Byker Wall, have managed to rebrand themselves as good quality and spacious housing for creatives.

That heritage of Brutalism in the North East, and all around the UK, that we are losing is deeply important. It is deeply inmporant not only from a conservation point of view, but politically too. It is not exaggerating to say that the Brutalist building movement of the 1960s and 70s was the last time there was an ambitious series of public works that prioritised the building-needs of ordinary people, not just businesses or the wealthy. The Brutalist estates cleared away slum housing that lacked basic amenities, like indoor toilets, and replaced them with people-centred complexes designed to promote interdependence and a shared stake in each other’s lives.

It would be deceptive to claim that these noble values always translated into reality (as Killingworth Towers proved), and I can understand my Mam’s generation’s scepticism about the shoddy execution of some major Brutalist projects, but these flagrant examples of poor practice has served the political purposes of those with no interest in good quality housing and services for working-class people. The defeat of Brutalist ideas is a victory for the unscrupulous property companies and landlords.

Revisiting Brutalism as someone who has become an adult in an era of precarity, austerity and housing crises, it is hard not to pine for those bold public ambitions, in spite of the valid critiques that are made of certain examples of Brutalism. The late great Mark Fisher described Millenial affection for Brutalism, in contrast to their parents' generation, as a sadness for a "lost future" - seeing a movement and vision of progress strangled at birth by neo-liberalism.

As we lose more and more of these buildings, we should begin asking more probing questions about why they must disappear; in whose interest are they vanishing? Is it because they are ‘hideous’ or ‘shoddy’, or is it maybe because they represent an era when luxury apartments were not the apex of architectural ambition?

Written by Calum Sherwood. Follow me on Twitter at: @CalumSPlath

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It's not you, it’s me": Why I will be voting Remain

I genuinely thought at the start of the EU referendum campaign I might vote to leave. Like a lot of people, I find the EU quite alienating and distant; I saw Greece being torn apart on the news due to cuts being imposed by the EU, and I wasn't sure why I could vote to remain a member of an organisation which seemed to put up borders with the rest of the world to look after its own.

However over the course of the past few weeks I've seen how this vote is actually about what kind of Britain we want to live in. Outward looking, tolerant, proudly multicultural and part of something bigger than ourselves. This referendum isn't so much about what we think of the EU as about how we view ourselves. For once the old break-up cliché, “it's not you, it's me”, is the reason to stay together.

My political hero, Barbara Castle, wrote when she became a member of the European Parliament despite years of opposition to the EU: "politics is not just about policies: it is about fighting for them in every available forum and at every opportunity".

I, like most British people, remain mildly Eurosceptic. I think the EU is not a perfect structure, and it has questions to answer about how it will make migration fairer and how it will ensure the inviolability of national sovereignty, particular in Southern Europe. However I do not think that this scepticism will be best served by surrendering our seat at the table; it will be best served by making our views heard as a partner and equal.

Tomorrow I'll be voting to Remain because I think Britain can achieve something better, for ourselves and our neighbours, by arguing for a better vision of Europe. We can only do that by maintaining our sense of ourself, by refusing to endorse a politics of fear and racism, and continuing to lead in Europe on inclusivity and equality; I'm frightened that a Britain which votes to isolate itself will not be in the position to argue for a better world.

Written by Calum Sherwood. Follow me on Twitter at: @CalumSPlath

0 notes

Text

The Finale

The Finale

By Florence Anderson

We often wondered, when it would end,

And how it would end

And sometimes, even if it would end.

The uncertain days of spring, yielded to the golden days of summer.

Sun-baked days, warmed by the joys of rediscovered

comradeship, solidarity and purpose,

defeating the cruelty of indescribable hardship,

but solid days departed, and scab days arrived.

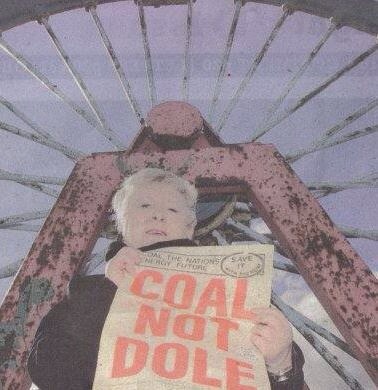

As November gloom descended on the pithead gear,

silhouetted skyline of Hetton town,

days of conflict, days of fear, police invasion and mass arrests.

Christmas awaited with bated breath.

Would we make it? Would we break?

The gloom abated for a while, spirits uplifted by turkey and wine,

picket vans, tinsel-decorated,

proclaimed the remaining days to the season of goodwill.

Childrens’ parties, French toys, German clothes, and Russian food, intense cold,

But we survived.

The road was clear for a victory,

But some were blind, they could not see,

and some were deaf, they would not listen.

Picket line broken, panic ran free.

Rumour to blame, sackings were due, Team Valley notices signed and sealed.

Reason abandoned, the battle bus filled.

Comrades departed, families torn.

My only regret, experience not shared,

the return to work, I was not there.

International solidarity determined I be far away,

in the Swabian Alps, land of mountains and fairytale castles.

Another world, another planet, a million miles from picketline battle.

But through the wonder of modern technology

I saw the families of Mardy, their pride still in tact,

And I wept with love for my culture and my class.

No glory achieved,

in might over right, police hands tainted,

we’ll never forget.

Salute those at Eppleton who returned with the banner,

The standard of struggle, the standard of honour.

Salute the women who marched at their side

With children who suffered but never complained.

History assured for those who resisted

the plan of destruction Thatcher devised,

the strike had ended, they did go back,

heads held high

Remember forever: 84, 85.

This poem was written by Councillor Florence Anderson, councillor for Hetton-le-Hole, about the end of the Miners’ Strike. Councillor Anderson led the Eppleton Area Miners’ Wives Support Group and has campaigned for peace and socialism through her support for The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament throughout her life.

This poem was used as inspiration for the folk song “The T-Shirts and the Blood” by Ed Pickford.

0 notes

Text

Walthamstow peace protests: a microcosm of the neo-liberalisation of the media industry

Now sufficient time has elapsed since the event, it’s important those on the centre-left look back over the peace protests in Walthamstow and ask why the press were so quick to believe and report that the Don’t Bomb Syria protest last year had been threatening, violent and outside an MP’s home - when in reality it was peaceful, community-driven and outside an MP’s constituency office situated in the hub of the area. Obviously, it was on some level about agency-driven decisions by individual journalists, either wanting to believe the story or using it to serve a political purpose. There was certainly an element of wilful ignorance - as well as genuine naivety or trust in the events reported as fact.

However it can’t be removed from the the neo-liberalisation of journalism as an industry. Poorer paid reporters, stricter deadlines, quantity over quality, fewer full time news reporters capable of doing long-term and thoughtful investigative journalism. Instantaneous reaction and the replacement of reporting with opinion, mainly because it’s cheap. Social media provides a shortcut to opinion presented as fact, and skirts around all these structural barriers imposed on the industry by neo-liberal rationalisation.

This isn’t to excuse the journalists who misreported the facts, or the disproportionate coverage the misreportage got compared to the subsequent clarifications. Rather the reportage of the Walthamstow protests was a microcosm of all these forces in political journalism, and there are important lessons to be observed in how the media operates and the constraints within which it reproduces information. I’m a bit of an unreformed Althusserian, but as always, a structural analysis really is key.

Written by Calum Sherwood. Follow me on Twitter at: @CalumSPlath

0 notes

Text

“The insanity of world-annihilation”: the political views of Sylvia Plath

This week we discovered Sylvia Plath invented that most shady of insults: “basic”.

“You are such a basic character yourself, anyway”, an 18 year old Plath wrote scathingly of a blind date.

Even in 2015, 52 years after Plath’s death, we are discovering the continued relevance and impact Plath has had on our culture. However, very little has been written about Plath’s politics - her worldview, and how her art was influenced by her values.

Plath is often written about as an apolitical artiste, too preoccupied with her own insecurities to have opinions on the world around her. Indeed there have been deliberate attempts by Olwyn Hughes, Ted Hughes’s sister and executor of Plath’s literary estate, to downplay Plath’s political activities through close editorial control of biographies. This version of Plath is simply not true.

Plath was optimistic and hopeful for the human race, even if she was disappointed by the politicians of her day. She was anti-establishment, strongly opposed to colonialism and American foreign policy. She was politically active, a campaigner and political party follower. As an ardent Plath-ist, I feel it my duty to write something which will go some way to illuminating the political side to Plath so often unexplored.

Religion was a formative influence on Plath’s views, particularly the pacifist beliefs Plath held throughout her life. Raised as a Unitarian, a non-conformist and liberal sect of Christianity, Plath dabbled in Methodism and later in life attended ceremonies in a Church of England parish. She even became involved in the supernatural, with a spirit guide called ‘Pan’ who she said assisted in the writing of some of her poetry. Although never remarkably religious - describing herself as a “pagan-Unitarian at best” - the radical and progressive brand of Christianity she grew up with ensured she was drawn to the outsider and the underdog, even in spite of her relatively privileged upbringing.

In 1950, at the age of 18, Plath published an essay in the Christian Science Monitor entitled “A Youth Appeal for World Peace”. A stinging critique of the arms industry and the arms race, Plath was disgusted by the politics of the Cold War and the state of anxiety and death US politicians were promoting. As a young pacifist, Plath became involved in the World Federalist Movement, an organisation critical of the United Nations’ ability to ensure lasting world peace. Plath was motivated to become involved in the WFM after witnessing the UN’s handling of the Korean War, writing that the conflict made her “physically sick”. At the height of the US’s patriotic fervour, Plath was a dissenter and felt alienated from the foreign policy of her home country.

Plath’s opinions were not confined solely to international politics; she was affected by the domestic politics of both of her homes, the US and the UK. It is fair to assume that Plath’s personal beliefs were too left-wing for either of the major US political parties, never registering as either a Republican or Democrat. Writing to her mother, she urged her not to vote for Richard Nixon - “a Machiavelli of the worst order” - yet she was similarly unsure of Kennedy too. Alienated by the American political mainstream, Plath dedicated herself to more cultural politics, taking up a job as a student journalist at college with an interest in current affairs.

Her anti-establishment politics were never clearer than the obvious sympathy she felt for the Rosenbergs, two alleged Communist spies in the US who were executed for treason. In Plath’s diaries, and in The Bell Jar, Sylvia and her novel’s protagonist Esther are both disgusted by the callous attitudes of many Americans towards the execution. This is particularly significant as the Rosenbergs represent “An Enemy Within” comparable today to homegrown Islamic terrorists. To sympathise with the Rosenbergs was to see humanity in a monster, who puts your own family at risk. Plath was always capable of compassion, even towards those she was told were her enemies.

Her political sympathies in the UK were more apparent. While at Cambridge, Plath became a Labour Party supporter, and a member of Cambridge Labour Club.

“I am definitely not a Conservative”, Plath writes firmly. She appears to hold the Liberals in similar disdain, writing: “The Liberals are too vague and close to the latter (the Conservatives)”. She even entertains the idea of attending some meetings of the Communist Party - “just for fun”, she adds. She later writes with ambivalence at the Communist group in Cambridge breaking up in response to the Soviet invasion of Hungary.

It is the Labour Party whom Plath is believed to have supported throughout her time in England. She was a great admirer of Hugh Gaitskell, the Labour Party leader at the time, whose eloquence she admired. His death, only slightly before Plath’s, would have been in the newspapers Plath read at the time.

Yet disarmament and pacifism remain the most consistent political thread which runs throughout Plath’s life. A few years before her death, Plath became a supporter of the “Ban The Bomb” campaign, an early initiative of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Plath wrote a detailed account in her letters to her mother of taking her young daughter, Frieda, on a “Ban The Bomb” march in 1960:

“I saw the first of the 7-mile long column appear - red and orange and green banners, “Ban The Bomb”, shining and swaying slowly… I saw myself weeping to see the tan, dusty marchers, knapsacks on their backs - Quakers and Catholics, Africans and whites, Algerians and French - 40 per cent were London housewives.”

Plath goes on to describe the pride she felt at having taken Frieda on her first protest: “the baby’s first real adventure should be as a protest against the insanity of world-annihilation”. Plath’s pacifism is even present in poems such as “Bitter Strawberries” and “Mushrooms”, where she alludes to the harsh climate of the Cold War and the destructive capacity of the atomic bomb.

Plath later wrote that “Frieda is my answer to the H bomb”.

In these few words you get a sense of Plath’s outlook - a belief that next generation has the capacity to be more peaceful than that which came before. Far from the introspective nihilist she is so often described as, Plath’s ambition was greater than for herself - it was for a world more peaceful than that which she experienced.

Written by Calum Sherwood. Follow me on Twitter at: @CalumSPlath

1 note

·

View note

Text

How I’m voting in the Labour leadership election

Not that I think my choices will matter much or be of interest to anyone else, but I felt it worth writing (perhaps for posterity’s sake) how I will be voting in the Labour leadership and other internal elections.

Mayor of London

1. Diane Abbott

Diane Abbott is the Labour politician who inspires me most. She has been at the forefront of progressive politics in this country since her election as the first black woman MP in 1987, and as Mayor will make London a fairer, greener and more tolerant place. Diane will never give quarter to anti-immigration rhetoric, and will champion the women and minorities who make London the brilliant and unique place it is. When we will have such a short turn-around time from choosing our Mayoral candidate until the election, Diane by far has the greatest name recognition and a record which is instantly recognisable as in tune with the priorities of Londoners. Diane has been both a maverick and a team player; willing to speak out when the Labour Party has strayed too far from its principles, but also serving in the Shadow Cabinet as an excellent Public Health Minister with fantastic policy ideas and work ethic. In my eyes, there's only one choice for Mayor and it has to be Diane.

Leader

1. Jeremy Corbyn

2. Yvette Cooper

3. Liz Kendall

4. Andy Burnham

Corbyn vs Cooper

After a lot of soul-searching, I’ve decided voting for Jeremy Corbyn is the right thing to do.

I have a great amount of respect for Yvette Cooper, who has defended Labour spending and is someone who I find a genuinely talented politician. Her policies on tackling domestic violence and championing women’s rights are second to none. But what I hoped Yvette would do over the course of the campaign is unequivocally champion a Keynesian vision for Labour’s economic agenda, a hard-headed economic rejection of austerity, and unfortunately she has failed to do so. By denouncing the idea of People’s Quantitative Easing, an idea supported by respected Keynesian economists like Paul Krugman and Ann Pettifor, it showed to me that Corbyn is the only candidate who can be trusted to articulate a pro-spending, pro-growth position.

Gordon Brown is a politician for whom I continue to have the utmost respect (perhaps an unpopular position amongst Corbyn supporters at the moment). Brown’s championing of spending to alleviate poverty and stimulate growth made a massive impact on the well-being of my working-class family from the North East, an impact that we still feel to this day. However, keenly following the campaigns of the four leadership candidates, I am not sufficiently convinced that Brown’s economic arguments will continue to be made unless Corbyn is victorious.

Regardless of who wins, I think Corbyn and Cooper would both make good, principled leaders. But it is Corbyn who offers the most hope for families like mine – and that is the reason I even care about politics in the first place. The anti-Corbyn camp say that a vote for Corbyn is privileged or careless; I find this an insulting line of argument. There is too much at stake in politics to gamble with my family’s security. Yet if politicians fail to make the arguments that will improve my family’s lives most - a prosperous welfare state, a well-funded NHS, spending money on jobs instead of war – then their lives will never improve. I could only kick myself if I threw away the opportunity to elect a leader who will try to persuade people of the fact that austerity is not only harmful, but terrible economics. The only thing that is guaranteed in this election is that Corbyn will make these arguments, and they are arguments I think will win with the public.

Kendall vs Burnham

Who you preference third and fourth is as much symbolic as it is trying to influence the result. Liz Kendall is someone whose politics are anathema to mine in a lot of ways. I have vehemently disagreed with calling her a Tory, as I do not doubt that her principles are more similar to mine than to a Tory’s. I subscribe to the Wilsonian maxim that the Labour Party needs a right wing and a left wing in order to fly. However her policy conclusions are not what I think will win for Labour; they represent a turbo-charged Blairism that has lost touch with the idea of differentiation, and have lost faith in providing a coherent challenge to the most right-wing Tory government this country has seen. I think her leadership would be divisive, her policies would be demoralising, and she would be the most right-wing leader the Labour Party has ever known. What I can say about Liz is that she has run an honest and straight-talking campaign – I know where she stands and she has stuck to her guns, and that is admirable, even if I disagree with what guns she has stuck to. She has faced sexist abuse from all sides, and I can’t help think that on a personal level, she seems a laugh. We might not agree on much, and I don’t think she’s right for the party or the country, but I can at least respect her for her tenacity and fighting a good campaign.

The opposite can be said of Andy Burnham. From launching his campaign in the City, denouncing workplaces where “only one person speaks English” (a statistical near-impossibility and dog whistle politics of the highest order) and claiming Labour spent too much in office, Burnham has flip-flopped to offer a reheated Milibandism in the wake of ‘Corbynmania’. He has embraced Corbyn one day and then made jokes at Corbyn’s expense the next; he has positioned himself as “the only candidate capable of stopping Corbyn” one day while acting as Corbyn’s greatest defender the next. From being the most pro-Iraq War candidate in 2010, he has now questioned whether he would back airstrikes against ISIL. I can honestly say I do not know what Andy Burnham thinks or believes, except that he believes that he should be leader of the Labour party. This is on top of the sexism which has emanated out of his campaign team (accusing Cooper of deploying tactics from the “Ed Balls playbook” was a new low), as well as the continued question mark over his LGBT voting record. I think a Burnham leadership would be disastrous.

Deputy Leader

1. Angela Eagle

2. Ben Bradshaw

Angela Eagle is by far the most qualified candidate for the position of Deputy. She has always been a fair democrat within the party, who genuinely believes in giving members’ more say over policy. She has run a pluralistic campaign, which has emphasised her faith in the wisdom of members. As a gay woman, Eagle will ensure Harriet’s legacy of championing equality in the party is continued. I also have the most faith in Eagle to manage an undoubted period of change; her experience and forthrightness is exactly what is needed from a Deputy when the party is at such a crossroads such as this.

Ben Bradshaw does not share my politics in a lot of areas, but I genuinely respect his outspoken support for Palestinian rights. This is particularly unexpected considering Ben sits on the right of the party. This is important as he ensures the case of Palestine is heard by an audience which is not always sympathetic to their plight. Having lived in the South West at uni, I can recognise that Ben has a unique perspective on campaigning as one of the few Labour MPs in the South of England.

As a gay person, I feel proud to voted for two gay candidates.

Conference Arrangements Committee

Katy Clark

Jon Lansman

NPF Regional Representative – London

Peray Ahmet

Nicky Gavron

James Murray

NPF Regional Representative – London – Young Labour

Jack Falkingham

Jack might not be from the same ‘wing’ of the party as me, but he is a good friend, and has worked tirelessly on the Labour Campaign for Mental Health. This is an issue very close to my heart, and I think Jack has been a fantastic advocate for this cause. He is also really nice about Newcastle, so I approve of his pro-Geordie policy stances ;)

0 notes

Text

The Labour leadership candidates should turn to Barbara Castle

As the Labour leadership election picks up pace, and some of the dividing lines between the candidates are beginning to emerge, I feel that it is becoming increasingly necessary for the some of the so-called frontrunners to revisit the career of Barbara Castle.

One of the most esteemed figures from Labour’s history, Castle proved that power is not incompatible with principle and providing a real opposition to Tory policy. Her politics in government and opposition always drew the red line of championing the cause of ordinary people. What would she have made of some of the triangulations over fundamentals, like welfare and immigration, on display today? I imagine she would have had stern words for those entertaining the idea of supporting a welfare cap or playing dog-whistle politics about “factories where no one speaks English”.

Castle has a rare place in the Labour Party as a figure who was always of the left (and never forgot she was of the left) but was decidedly unafraid of “getting her hands dirty” in government. In the act of “getting her hands dirty”, she was willing to compromise some of her ideological purity in the name of advancing the left as a whole.

An oft-cited criticism of Castle’s record from the left, sometimes used to dismiss Castle’s legacy as a socialist, is over her approach to trade unions. Castle’s proposal to introduce compulsory ballots before a strike, known as In Place Of Strife, was one episode from Castle’s vast career, and an episode in which she was defeated. To reduce all of her legacy to In Place Of Strife while ignoring her leadership of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, championing of Commonwealth immigration, steering great material and social advances in the rights of women, and pushing to abolish private medical practice, is dangerous and risks sacrificing Castle’s legacy as an important and successful Labour figure from the Labour left.

Castle’s isn’t a story of purity, and that is why I think she is important; hers is a story of achieving and using power to advance socialist causes. To Castle, both the “achieving” and “using” were equally important. Unlike New Labour, who saw the achieving of power as an end unto itself, Castle showed how radicalism could redefine political orthodoxy and make socialist policies, such as the Equal Pay Act, the mainstream.

Castle continued to remain a champion on the left of the party throughout her life, despite the sexist abuse she faced at times from so-called comrades (sexism was never far from her battles with the trade unions). This determined rootedness in the principles of the left, despite reaching the top table of government, show a roadmap of how to negotiate power with principle that the Labour leadership candidates should study.

Castle knew how to win, and electoral success is a raison d’etre of the Labour Party, but Castle should remind any would-be leader that the route to power is not through selling out those who the Labour Party exists to represent. Castle should also act as a reminder that women and minorities in the party are not there to be belittled, and would caution against any attempts from the left to endorse an all male ticket for leader and deputy.

Labour has fewer figures more popular or successful than Barbara Castle – her diaries are worth a reread before any decisions are reached.

This article was originally published on Left Futures.

0 notes

Text

Trident could be Labour’s issue of consensus, principle and pragmatism

It has been several weeks now since the Tories attempted to portray Ed Miliband as a “stab-in-the-back” traitor bent on surrendering Britain’s defences – an episode in which Trident became an unexpected focus of the campaign trail for a brief time.

Tory attentions have since moved on to other ludicrous topics to illustrate Miliband’s duplicity and skulduggery. Taking the shrill fever pitch of anti-equal marriage campaigners a step further, now they claim a Miliband government would be “anti-marriage” in its entirety. We wait with baited breath to see where they will go next.

However, despite the bottom of the barrel nature of Michael Fallon’s attack on Miliband, the episode was striking in how little debate had been had during the past 5 years over Britain’s nuclear deterrent. As the polls continue to be in deadlock, Trident has the potential to be an issue of consensus on which any Labour minority government could garner support from smaller parties and from the public.

In Miliband’s foreign policy speech last week, he described himself as “a disarmer – but not a unilateral disarmer”. This was clearly a demonstration of Miliband’s continuing commitment to Trident, yet Miliband is an astute politician who knows his history. He will not be unaware of the lack of progress in disarmament the multilateral approach has yielded.

Britain is under obligation, under the terms of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, to make active efforts to disarmament with the ultimate goal of a world free from nuclear weapons. Under the auspices of multilateralism, the UK is no closer to total disarmament than it was 47 years ago when the treaty was signed.

Tory and Labour governments have consistently rejected the calls for a nuclear weapons convention at the United Nations – something Miliband in the spirit of his commitment to playing an active role in the foreign affairs should support. Replacing Trident would say to the world the UK is dedicated to another 50 years of nuclear weapon possession, and fly in the face of our obligations to the NPT to lead on disarmament.

In the instance of a minority government, Miliband as Prime Minister could explain to the country that in times of economic hardship, £100 billion on weapons of mass destruction are not a priority. A far greater priority is ensuring the money is used to fund our public services, as well as repairing our damaged reputation abroad by taking bold decisions to meet our international obligations.

Two of Miliband’s closest and most trusted advisors, Lucy Powell and Stewart Wood, are believed to be supporters of unilateral disarmament; Lucy Powell committed in her selection for Manchester Central to opposing Trident replacement, while Stewart Wood is rumoured to have advised Miliband to commit to scrapping Trident during the election campaign. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that in government, Miliband could heed the advice of those close to him that faced with cutting social services and cutting nuclear weapons, the public may favour the latter.

Similarly there is increasing pressure from Labour parliamentary candidates for Miliband to take a firmer line of supporting disarmemnt. 75% of PPCs standing for Labour in 2015 opposed Trident replacement when surveyed, demonstrating that Parliament’s make-up may be the most hostile to Trident in a generation.

Job losses are often proffered as a reason for the maintenance of Trident from a progressive standpoint, yet this has been debunked by a recent report by Scottish TUC and Scottish CND. According to this report, as few as 600 jobs would be lost from disarming. At £100bn in cost to protect around 600 jobs, some have been prompted to describe Trident as “the most expensive job-creation scheme in history”. Miliband should argue that the skills used in the creation and maintenance of Trident could be diversified into fields such as sustainability and environmental projects.

Turning Trident to Labour’s advantage could be a demonstration of Miliband’s pragmatism; by offering Trident as an area for consensus, he could guarantee more vital support for Labour’s spending plans from other smaller parties, most notably the SNP. Scrapping Trident would show that a Miliband government would rather invest in providing for the most vulnerable, while also taking a bold approach to foreign policy similar to his principled stance on Syria.

In a climate when the public want greater differentiation from their politicians, while also desiring leadership which is tough and principled, Trident stands out as the obvious issue around which Labour can build consensus for its agenda of social progress and international cooperation.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Florence Anderson's speech to the Murton Miners' Rally - Durham Miners' Rally December 1984

“Today, I would like to turn the tables a little, because on behalf of the women, I would like to pay tribute to our menfolk. To the miners of this country, who have stood up and been counted, not just to defend their jobs, their communities and their union, but they have stood up and defended the dignity of the working class. Can I say publicly, that I salute the pickets. I salute the pickets, the men and the women, who have demonstrated in the time-honoured tradition of the British trade union movement and said to the scabs, you shall not pass unhindered. To hear some people, you’d think that they were creatures from outer space who had just descended. But they’re not. They’re husbands and fathers, sons and brothers. They’re wives, mothers and sisters. And we should stand proud of them too, because they are our frontline defenders against the war of oppression that has been thrust upon us by Thatcher and her Tory government. And you hear the Tories scream about the mass picketing, and I heard this recently in a debate at Tyne and Wear, about all these mass pickets. And at the same time they talk about the miners sitting at home wanting to go back to work. Well you can’t have it both ways, because I think the truth of the matter, is the sight of the working class standing together frightens the hell out of them. They talk about violence, and they know about violence, because they’re the masters of it. Since 1979, we have had a violent government pursuing violent policies against the working class. During the past nine months, we experienced violence. Violence from the State in the crudest form. We’ve had the DHSS regulations, which have robbed women and children of fifteen pounds, and now sixteen pounds, a week and that is responsible for the acute poverty which now exists amongst mining families. And we’ve seen the violence of the Electricity Boards, who are demanding unreasonable payments in order to continue the supply. I’ve seen dozens of people in the last few weeks, ordinary decent people with little children, who come to me for help because they’re under threat of having their electricity disconnected. That’s violence in my book. And of course we’ve all seen the violence in the courts, of the anti-trade union legislation, which no doubt your President is going to be referring to later. But most horrific of all, we have seen and we have experienced the violence of the state police whose brutality will never be forgotten and never forgiven. My own village of Hetton has played unwilling host to hundreds of police. That’s if you can call them police, because to me some of them are no more than animals in uniform. I think that’s why we recognise completely that they are strike-breaking. And I’ll never forget the horrible spite, of hundreds of police lined up at Eppleton when the first scab went in there, it really is a quite disgusting sight. And I’ll never forget walking along with the Women and Wives’ Support Group and every police van that passed we got that *middle finger* from them, that’s the contempt we got from the police. And I won’t ever forget being arrested a few weeks ago, and I don’t suppose there’s many people in this Hall who have been arrested during the Strike. And have you noticed when the police arrest you, they automatically think you can’t walk anymore? Now you see, I haven’t got very good posture as you can see, so they thought they can get your neck, and go like that, and then they sort of throw you in the van. And those other two women arrested with me, with two men, and we were sitting there in this little van like sardines, shoulder to shoulder, and this young copper sitting next to me lands another charge on me. He says, “stop you leaning up against me”. So I says, “honey, I’m particular who I lean up against!”. And you’ve got this one opposite you see, and I says, “I have never in my life witnessed such violence”. And he says, “You? Married to a miner?”. So I says, “honey, the miners stand head and shoulders above you”. But I never ever dreamt that I’d be hauled before the courts in my lifetime, and I don’t think many of the thousands who have been before the courts would ever thought so too, but it happened. And I think it should be a concern for women and children, who look on the police now with fear. And this is true, because I was in Hetton one day, and there was a woman standing there with her little boy, just down beyond picket line, and then the scab kind came and all the police run up. This little laddy stood there, and says to his Mam, he says, “Mam, I’m frightened”, but stood there, and he saw. And I’ve been shopping, and there’s children there, and they look at police and they’re afraid. But do you know, can I tell you this, that the politics of this strike do go into the playground. And I think that our children have been broke throughout this strike, they’ve been deprived, but in the playground they sing, “I’d rather be a picket than a scab”. Because scab is the most contemptible word in the English language, and those who sit in those obscene little vans with their blacked out windows and their mesh guard: they haven’t just sold their principles. They have sold their souls. They haven’t just betrayed us and our children, who have suffered all these 9 months. They have betrayed their forefathers and their Union. They have betrayed people like my Father, who in the 1930s couldn’t get a job in the Durham coalfield because he was blacklisted for being a trade union activist, and he had to end up before nationalisation in the Orkney Islands. And every scab who crosses the picket line, he’s assisting Thatcher, in pushing us not back to the 1930s, but to the 19th century. Now to me, a picket line is sacrifice, and it should be to every trade unionist. And if this principle had been upheld, we should have achieved our victory a long time ago. Comrade Chairman, I’m a member of the Labour Party. I’m a Labour councillor. I’m a very small cog in the machinery of politics. But I am to be a woman of total commitment to the miners’ cause, which I believe is fundamental to the whole of the labour movement. But I do wish I could hear the same talk and commitment come from the national leaders of my party. I don’t know how many times last year that we heard the pledge, “when we get back into power, we’ll look after our people like she’s looked after hers”. Well you know, if you cannit defend your own people when they’re having everything in the book thrown at them, you’ll never achieve office, because you’ll have lost your credibility.” Councillor Florence Anderson, Labour councillor for Hetton-le-Hole, led the Eppleton Area Miners’ Wives Support Group and has campaigned for peace and socialism through her support for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament throughout her life. Transcribed by Calum Sherwood from the original recording of the speech.

1 note

·

View note