Text

the miseducation of Lauryn hill!!!

Goddamn, this album is good 🎧

#spotify#best music ever#lauryn hill#wordstoliveby#throwback#life quotes#life lessons#dancing#dancemood#mary j. blige#d’angelo#doo wop

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

💿 OutKast!! 💿

#Spotify#SoundCloud#outkast#best music ever#happy music#my music#my stuff#1990s#music#hip hop music#dancemood#dancing#andre 3000#ice cold#big boi#hey ya!#roses#so#sofresh

1 note

·

View note

Text

💿 BADBADNOTGOOD 💿

Best songs from the album tbh⬆️⬆️

[as] lol.

Probably the best trend rn

youtube

#Spotify#Youtube#tiktok#best music ever#badbadnotgood#time moves slow#in your eyes#[as]#good vibes#chill#my music#music

0 notes

Photo

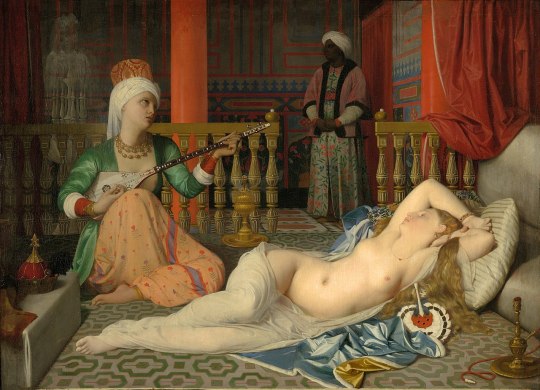

Odalisque with Slave, 1839, by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867)

Why Victorians Went Crazy for Orientalism

During the period of feverish obsession with Orientalism, European artists and art lovers looked towards what they dubbed the “East” - aka the “Orient.” The Victorians weren’t overly specific, as this region actually spans many distinct territories and cultures over the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia. They all did have one sure thing in common however, their “otherness.” They were decidedly different from European culture and while the obsession of the Orient has stretched quite far back in history (and I mean centuries before), we’re going to focus on how and why the Victorians in particular went crazy for it - particularly their obsession with the Ottoman Empire.

The idea of the “Orient” often sets the scene in one’s mind as slave markets, snake charmers, women either dressed in too much clothing or none at all, the hustle of markets and harems, as ‘Arabian Nights’ from Disney’s Aladdin plays in the background. These are just some of the stereotypes which continue to dominate much of the region(s) rich cultures and histories. Provocative, erotic, and exotic.

Power and Obsession

Society at this time held an appreciation of the complex architecture, but often little else, interested only in what the artists could portray as consumable to an audience - whether it was an accurate representation or not.

They largely pushed the view of East civilizations “otherness” through unrealistic portrayals of its people. Clearly all Arab men were snake charmers or slave traders, and all women were poor sexy slaves or… sexy slaves with slightly more luxurious lifestyles - “sexy slave babes” as Lindsay Ellis playfully coins in her video essay ‘The Most Whitewashed Character In Literary History.’ It largely represented these cultures stereotypes or fantasies from the Victorians outside perspectives.

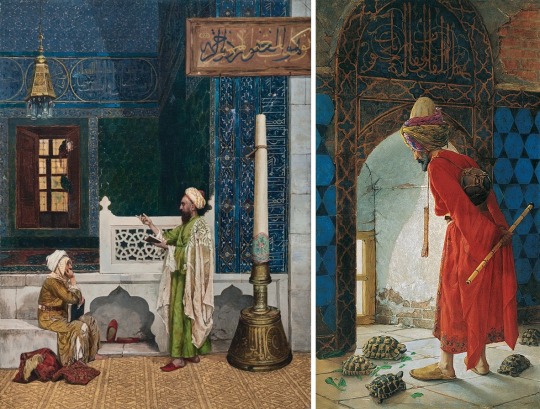

For example, look at the amazing care Osman Hamdi Bey, an artist actually born within the Ottoman Empire, took in portraying the architecture and lettering within ‘Reading the Quran,’ and ‘The Tortoise Trainer.’

While Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting ‘The Snake Charmer’ isn’t as grounded in reality.

These portrayals, which didn’t just occur in visual art but also frequently in literature and the World’s Fair, created a narrative in which the Western control of the East made them civilized and justifying that good ol’ colonial spirit.

Breaking the Nude Rules

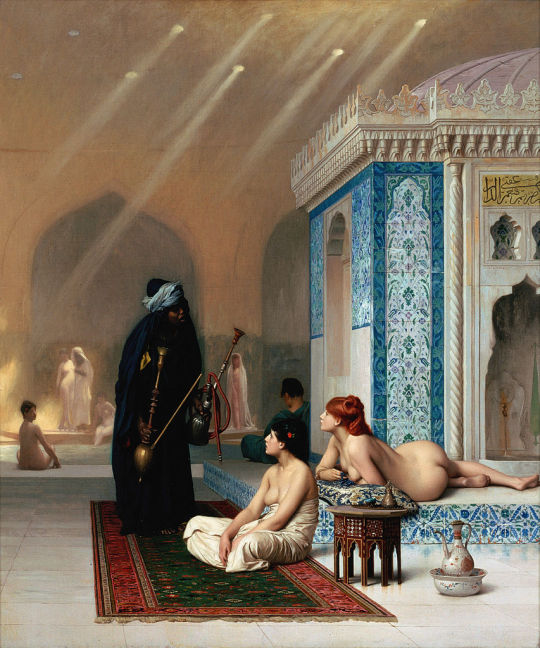

Nudity was a big thing for the Victorians. Today we regard them as shrewds scared of showing their ankles, but they went nuts for scandal and drama. Traditionally in Victorian art, nudity had to hold a purpose in order to be deemed acceptable. This included requirements such as depicting mythological or allegorical figures. Then entered ‘Orientalism’ and with it an exception to the rule, where they could view as many naked sexy slave babes that they wanted! Orientalism was an exception to the Nude Rules within Victorian society, and Orientalist artists milked it. Depictions of harems within Victorian art could vary greatly, from some showing it as a more domestic space for women, to others dialed up the exotic and erotic to 100.

When seeing how the Harem was depicted in art by men in particular isn’t all that surprising, as it was the unrealistic portrayal of what was essentially the equivalent to an exotic form of an all-girls sleepover, equipped with nothing but pillows. In short, it was pure fantasy. This is largely due to the fact that men weren’t actually allowed in harems. Going back to Ellis’ video essay, these 19th century European men of course struggled with the “why can I not have the thing?” mentality, and so were naturally inclined to go off nothing but their sexy, sexy fantasies.

For example, let us view the harem through the male gaze with Jean-Léon Gérôme’s ‘Pool in a Harem,’ painted in the 1870s.

In comparison is Henriette Browne’s 1860 painting titled ‘A Visit: Harem Interior, Constantinople.’

Beautiful but Problematic

Orientalism, since the publishing of the famous ‘Orientalism’ by Edward Said, has been dubbed inherently racist by many. Many depictions were for sure inspired by colonialism and the want to patronising-ly differentiate civilizations. Adam Shatz in his article ‘Orientalism, Then and Now’ suggests that this hasn’t ended with the Victorians:

“Orientalism is still with us, a part of the West’s political unconscious. It can be expressed in a variety of ways: sometimes as an explicit bias, sometimes as a subtle inflection, like the tone color in a piece of music; sometimes erupting in the heat of argument, like the revenge of the repressed. But the Orientalism of today, both in its sensibility and in its manner of production, is not quite the same as the Orientalism Said discussed forty years ago.” - Adam Shatz, The New York Review of Books

The Victorians undoubtedly fetishized these cultures in the guise of documenting the culture. And these stereotypes continue to persist to this day. On the site for ‘Reclaiming Identity: Dismantling Arab Stereotypes,’ it’s described how these views contribute to a larger (and inaccurate) view of the Middle East:

“‘Orientalism’ is a way of seeing that imagines, emphasizes, exaggerates and distorts differences of Arab peoples and cultures as compared to that of Europe and the U.S. It often involves seeing Arab culture as exotic, backward, uncivilized, and at times dangerous.” - arabstereotypes.org

Orientalist artists no doubt made visually stunning works of art, but delving deeper into identifying what makes them more fantasy than reality and the repercussions that came from that is far more important. These works often took away what made the cultures of these regions unique and interesting in order to push their own narrative, and push a consumer trend. When again looking at an orientalist piece perhaps ask yourself what aspects the artist is portraying; reality or fiction?

11K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Skulls, both painted in 1887, by Vincent van Gogh (1853 - 1890)

8K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Seeing Through Time, 2018, and Seeing Through Time 4, 2019, by Titus Kaphar (1976- )

Kaphar’s work might be familiar to you, as his protest paintings have been featured in (and on) TIME magazine. His works, notably his oil paintings but he uses various mediums, centers around the history of representation. As said in his own words, his “practice seeks to dislodge history from its status as the “past” in order to unearth its contemporary relevance.” They are about confronting the past and recognising how we are responding to it in the present.

Kaphar works in a way that takes traditional materials and transforms them into something completely new. This is extremely fitting as he uses his art to engage with social commentary and spread awareness on societal issues. Issues such as the US criminal justice system and racial inequality. In fact, he has TED talks including ‘Can Art Amend History?’ and 'Can Beauty Open Our Hearts to Difficult Conversations?’ that are certainly worth watching.

531 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Details in Red

Portrait of Isabelle Antoinette Barones Sloet van Toutenburg, 1852, by Nicaise de Keyser.

Patricipance of Venice, 1881, by Alexandre Cabanel.

A Young Lady Aged 21, Possibly Helena Snakenborg, 1569, by an unknown artist.

Portrait de la comédienne Marie-Anne de Châteauneuf, 1712, by Nicolas de Largillière.

Mrs. Hugh Hammersley, c. 1893, by John Singer Sargent .

Louise, Queen of the Belgians, 1841, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter.

Sabina Seupham Spalding, c. 1846, by Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz.

Elizabeth I, the “Pelican” portrait, c. 1572, by Nicholas Hilliard.

Portrait of Mary Louise of Orleans, Queen of Spain, c. 1679, by José García Hidalgo.

Portrait of Marguerite de Sève, 1729, by Nicolas de Largillière.

21K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Madame de Saint-Morys, 1776, by Joseph Siffred Duplessis (1725-1802)

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Detail of Madame de Saint-Morys, 1776, by Joseph Siffred Duplessis (1725-1802)

600 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Un Dejeuner, c. 1868, by James Tissot (1836-1902)

787 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Aperitif, 1881, by Émile Pierre Metzmacher (1815-1890)

761 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of Princess Zinaida Yusupova, 1902, by Valentin Serov (1865-1911)

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Modesty, 1749-52, by Antonio Corradini (1688-1752)

12K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Susan Walker Morse, c. 1836-37, by Samuel F. B. Morse

870 notes

·

View notes