I like to share and exchange ideas. Feel free to ask any question you want.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Women: “We don’t like being pressured into sex.”

Men: “WHAT’S GOING ON? Can we still talk to women? Can we still shake hands? Am I a rapist?! This is SO CONFUSING!”

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The most important measures to make the world better

Three important win-win-win measures to make the world better: https://stijnbruers.wordpress.com/2015/02/07/the-three-most-important-win-win-win-measures/

0 notes

Text

Free will relativism - A middle ground between Free will absolutism & Fatalism

According to some research, denying the existence of free will - such as claiming that our choices are determined since the beginning of the Big Bang - causes people to develop more fatalist, irresponsible attitudes. However, I think one needs to be careful with interpreting these results, because free will is an ambiguous concept. In this essay, I will first introduce some science about decision-making. Then I will talk about two extreme modes of thinking about decision-making: free will absolutism and fatalism. I will argue that both modes of thinking are plausibly harmful and fallacious. Finally, I will bring this dichotomy together in a cohesive, realistic whole: free will relativism, which is compatible with the science of decision-making. The Science of Decision-making According to science, we do the things we do because of continuous interactions between our bodies and our environment, which are both quite stable, yet ever-changing. Without the environment, there is no playground to act. Without our bodies, there is no act. The basic evolutionary function of the central nervous system is to coordinate the body in its environment, which is important to satisfy biological needs for survival, development and reproduction. Conciousness - one's ongoing experience - can be seen as an enhanced function of the central nervous system to allow a (more) flexible response mechanism (FRM) to coordinate the body in its environment. Through evolution, we developed the capacity to experience pleasant feelings toward what generally satisfies our needs and unpleasant feelings toward what generally threatens them. As a result, we as sentient beings experience problems subjectively. Decision-making, a part of the FRM, can be regarded as a problem-solving activity, which is terminated by a solution that is satisfactory to solve the problem at hand (f.e. find food). Conciousness provides the input data for decision-making, which is integrated information from the senses about the body and its environment and from memory based on past experiences. During the decision-making process alternative beliefs or courses of actions are identified, weighed and selected, which may or may not result in an action (defined as intentional, purposive, conscious and subjectively meaningful behaviour). It has been theorized (by Kahneman D.) that a person's decision-making involves two kinds of cognitive processes: an automatic intuitive system that is a bottom-up, fast, and implicit system of decision-making, and an effortful rational system that is a top-down, slow, and explicit system of decision-making. This theory is consistent with the idea of bounded rationality (Herbert S.), according to which people are only partly rational, and are irrational in the remaining part of their actions. People experience limits in formulating and solving complex problems and in processing (receiving, storing, retrieving, transmitting) information, and make use of mental-short cuts (heuristics) to make decisions (f.e. affect heuristic, availability heuristic, familiarity heuristic, representativeness heuristic). Free will absolutism Free will is oftentimes conceived as the idea that people ultimately cause their own choices, and are therefore ultimately responsible for their own actions. Although this idea - which I call free will absolutism - can be a powerful motivator to act and solve problems, it is bound to overestimate the role of choice and responsibility in the natural world, which may lead to: - magical, counterfactual thinking ("person X could have acted otherwise", “you can always control your own actions”) - negligence of problems ("the poor ultimately choose to be poor") - retributive punishment ("person X choose to behave badly, so s/he has to suffer") I believe free will absolutism is an extreme mode of thinking about decision-making and responsibility, and I think the idea is fallacious, because it artificially seperates ourselves from our environment, and assumes some kind of vague, magical “self” driving our behaviour. It obscures the fact that our choices are bounded by factors that aren’t within our control. People don’t cause their own choices ‘ultimately’, but only to a degree, depending on the information present in their brains, and the environment with which they currently interact. Fatalism The other extreme mode of thinking about decision-making and responsibility is the antipode of free will absolutism: fatalism. Instead of assuming that we are ultimately responsible for our own choices, fatalism assumes that we are ultimately irresponsible, and don’t cause any of our own choices. Fatalism allows to easily forgive oneself and others. Assuming that you don’t have a choice, can also be a powerful motivator to act in a certain way (“I have to do this, I have no choice.”). On the other hand, fatalism is bound to underestimate the role of choice and responsibility in the natural world (in a way that is relevant for humans), which may lead to: - negligence of problems (“we can’t control our own actions”) - prejudice about future actions (“person X will not be able to act otherwise”) - moral nihilism (“our choices don’t matter”) I think fatalism also artificially seperates ourselves from our environment. Everyday experience and science shows us that people are able to control their behaviour to a limited extent, although not in a magical or ultimate sense as described above. Even if all our choices are determined since the beginning of the Big Bang, it does not follow that we should be prejudiced about our future actions, because we can not know for sure what our choices will be in the future. It also does not follow that our choices wouldn’t matter, because (1) harm and suffering are bad by definition, so it matters to avoid them irrespective of one’s notions of free will, and (2) because we are bound to make decisions according to our needs, preferences or values. Fatalism only follows from a denial of free will if one resorts in black-and-white thinking about decision-making, where free will absolutism (“we always have a choice, we are ultimately responsible for our actions”) and fatalism (“we don’t have a choice, we can’t take responsibility”) are as two sides of the same coin: extreme modes of thinking about decision-making and responsibility. Free will relativism: a sensible middle ground A relativist notion of free will assumes that people have an ability to make choices and behave responsibly, but that some factors that influence their decisions are beyond their control. Therefore, we are not ‘ultimately’ free to choose (in the sense of autonomous or self-controlled) or ‘ultimately’ responsible for our actions, but only to a degree. I propose to conceive free will and responsibility as natural abilities (and not as magical givens), and to align these concepts with the science of decision-making. Free will relativism implies conceiving free will as the ability to make autonomous, self-controlled decisions, an ability that depends on circumstances, but which can also be improved. Similarly, responsibility can quite be conceived as follows: “I suppose responsibility is quite simply ‘the ability to respond’: when you question the things you do, you can give sensible reasons as to why you are doing what you are doing. Responsibility requires you to realize the consequences of what you do and the decisions you make. To me, responsibility really is an ability. As with other abilities, you can be(come) better or worse at it, and as with all abilities, responsibility is limited by natural factors. More knowledge and awareness commits us to more responsibility, despite the notion that our responsibility is bounded by the limited information we have, the finite amount of time we have to process this information and the cognitive limitations of our minds.” (one of my previous notes) I think this idea of ‘bounded responsibility’ (analogous to the idea of ‘bounded rationality’ has a couple of personal and social benefits. (1) It dismantles thinking black (fatalism) and white (free will absolutism), a cognitive distortion that may perpetuate the effects of psychopathological states such as depression and anxiety (fatalism assumes too little responsibility which may be depressing; free will absolutism assumes too much responsibility which may be terrifying). It also forms a buffer against moralistic judging about the decisions of oneself and others, and it enables forgiving oneself and others more easily. Moreover, it allows to focus on what’s more important: to prevent more harmful, irresponsible acts from happening (again) in the future. Blame and punishment should only be used if functional and needed to meet this goal, rather than being used as weapons to ‘fight evil’ or ‘compensate’ damage already done. A final note In this piece I proposed how to understand free will in a realistic way. Free will relativism is a form of compatibilism (the idea that free will is compatible with determinism). However, as I said in my introduction, free will is an ambiguous concept: based on one’s notions of free will, one may hold a different attitude towards it. Semantics matters. For example, Sam Harris asserts that free will does not exist and his view is also compatible with determinism and the science of decision making. Using the terminology in this piece I wrote, I would say he rejects free will based on an ‘absolutist’ notion of it. Resources If you are interested, this is a selection of resources that inspired me in writing this piece: Wikipedia: Bounded rationality, cognitive distortion, compatibilism, decision-making, fatalism, free will, ignosticism, magical thinking, retributive justice ... Books and articles: - Dennett, D. C. (2013). Intuition pumps and other tools for thinking. WW Norton & Company. - Earl, B. (2014). The biological function of consciousness. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 697. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25140159 - Gigerenzer, G., & Selten, R. (2002). Bounded rationality: The adaptive toolbox. MIT press. - Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan. - Verplaetse, J. (2010). Zonder vrije wil. Uitgeverij Nieuwezijds. YouTube: - Sam Harris on Free will

1 note

·

View note

Text

On the Evolution of Science

I recently read Matt Ridley’s book ‘The Evolution of Everything’. In his book he tackles the widespread myth that we can command and control the world – that we often go around assuming that the world is much more a planned place than it is. It is about our fascination by top-down direction and our blind spot for bottom-up emergence. In his book, he sets out to construct a sort of grand theory of evolution, that goes beyond the theory of evolution explaining the diversity of species:

“One of the great intellectual breakthroughs in recent decades is that Darwin’s mechanism of selective survival resulting in cumulative complexity is not only confined by systems that run on genetic information, but also applies to human culture in all its aspects. The evolution of human culture is surprisingly Darwinian: it is gradual, undirected, mutational, inexorable, combinatorial, selective and in some vague sense progressive. It was long believed that evolution could not occur in culture because it does not come in discrete particles, nor does it replicate faithfully or mutate randomly, like DNA. This turns out not to be true. Darwinian change is inevitable in any system of information transmission as long as there is some lumpiness in the things transmitted, some fidelity in transmission and a degree of randomness, or trial and error, in innovation. To say human culture ‘evolves�� is not metaphorical.”

Ridley demolishes the arguments for design and effectively makes the case for evolution in the universe, morality, genes, the economy, culture, technology, the mind, personality, population, education, history, government, God, money, and the future.

After reading his book I wondered: “What about science? Does science evolve too?”. Science is also an aspect of human culture, and one could argue that science is something that we humans intelligently designed to enable a better understanding of the natural world. (Wikipedia defines science as “a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the natural world”.) If anything, science seems like the pinnacle of human design and top-down planning. From another perspective, though, science can be understood as a cultural phenomenon offering bottom-up descriptions about the natural world, which emerged largely unplanned through evolutionary forces beyond human control. And so, as I thought about the question whether science evolves more thoroughly, interesting parallels between the evolution of life and a supposed ‘evolution of science’ came into mind. This is my take on it:

In life forms, the unit of transmission are genes. In science, the unit of transmission are hypotheses. Both evolve by selective persistence by at least partly random variation. Life forms are the carriers of genes, while minds are carriers of hypotheses about the world. As life forms migrate through the world, their genes migrate with them. If life forms have minds, their hypotheses travel with them as well. Genes are transmitted by reproducing life forms. Hypotheses are transmitted by communicating minds. Both genes and hypotheses evolve through natural selection. In life forms, environmental circumstances naturally select genetic varieties that are more suited. In science, experiments and observations naturally select hypotheses that are better at explaining and predicting observations in the natural world. This kind of natural selection is better known as the scientific method, which tries to explain and predict observations in a reproducible way. Natural selection explains the evolution of life by differential reproduction of genes. The scientific method explains the evolution of science by differential reproduction of hypotheses, which implies a survival of the fittest hypotheses. Hypotheses compete to explain natural phenomena. Hypotheses that don’t fit experimental evidence are either modified (cf. decent with modification) or discarded. Hypotheses that survived experimental testing may cooperate with other hypotheses, forming scientific theories - logically reasoned, self-consistent models or frameworks for describing aspects of the natural world. Testable explanations and predictions emerge and organize knowledge producing science. Nature experiments with clusters of cooperating genes producing life forms. Both genes and hypotheses recombine to generate infinite diversity and complexity. There is evolution of genes, cells, multicellular organisms and life as a whole. There is evolution of hypotheses and theories, physics, chemistry, biology and science as a whole.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

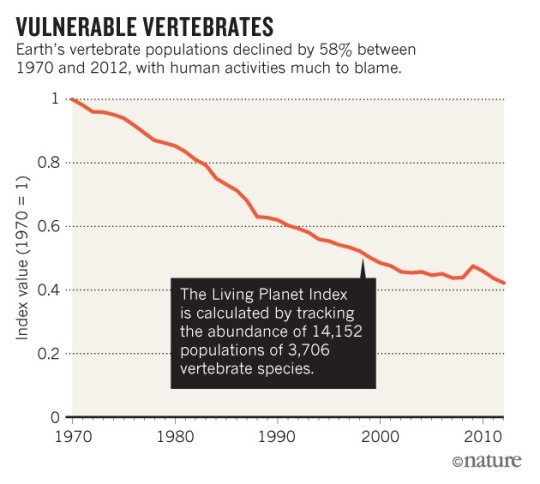

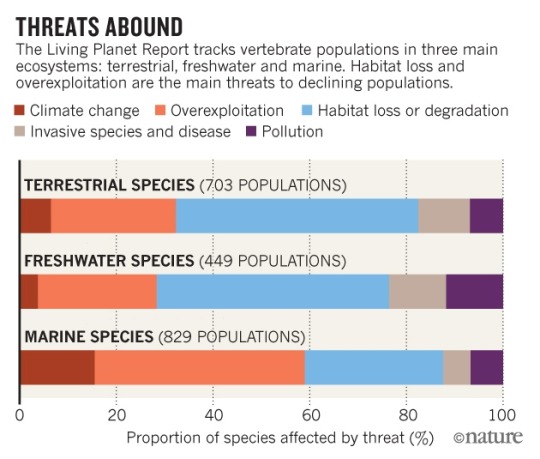

Wildlife in decline: Earth’s vertebrates fall 58% in past four decades

The populations of Earth’s wild mammals, birds, amphibians, fish and other vertebrates declined by more than half between 1970 and 2012, according to a report from environmental charity WWF and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL).

Activities such as deforestation, poaching and human-induced climate change are in large part to blame for the decline. If the trend continues, then by 2020 the world will have lost two-thirds of its vertebrate biodiversity, according to the Living Planet Report 2016. “There is no sign yet that this rate will decrease,” the report says.

“Across land, freshwater and the oceans, human activities are forcing species populations and natural systems to the edge,” says Marco Lambertini, director-general of WWF International.

Image Source: Living Planet Report 2016

337 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Redefining What it Means to Matter

I watched this video and want to share my opinion. To me, it is not that difficult to find meaning. If you know what it means to be happy, then you know maintaining it is meaningful. If you know what it means to suffer, then you know avoiding it is meaningful. To me these are simple truths, not some high moral standards. Our well-being matters, and if we think it doesn’t I believe we have been misinformed to the detriment of our self-respect and our care for others.

What does it mean to value anything? If it weren’t for us being sentient - our capacity of having pleasant and unpleasant experiences - I believe we wouldn’t be able to attach value to anything. Values are in a sense predictors of well-being, and this is why people can also value the wrong things: we can value things that badly predict happiness.

Then the question remains what we should value, that is: how can we support our well-being more effectively? To answer this question, I think we need to accept reality as it is and we need to adopt a proactive state of mind to make things better for the future. We need to gain understanding of ourselves and our circumstances through science and critical thinking, which will allow us to make better predictions, check our values and make better choices.

0 notes

Text

Nature, morality and responsibility

A good way to develop your ideas is to share them in public. That’s what I’m doing here. In this post I describe my current views on how to understand three important concepts (or so I believe): nature, morality and responsibility. Nature Nature, in its broadest sense, is anything present in the universe. Nature is reality. We humans are part of the universe, and thus can be considered natural. We have brains and senses that allow to make maps of reality, which enables to coordinate our bodies in our environment. If we want to accomplish certain goals, some maps will be more useful than others. I think scientific inquiry and critical thinking can make our maps of reality more clear and accurate, and thus more useful if a situation requires complex decision-making. Why? Science pertains to questions about nature ("what is") and I think it’s the most reliable source of information in principle. Critical thinking allows us to question our maps of reality thoroughly. Morality Morality pertains to questions about what is good. Can science inform us about moral questions? I think this depends on someone’s notions of morality. If one believes good and bad don’t really exist in the real world, than science can’t inform us to answer moral questions and thus make better choices. To me, this conception of morality makes no sense and doesn’t seem useful at all. I argue that "what is good" (morality) is a subset of "what is" (nature). Therefore, what is good refers to real-world, natural phenomenons. More specifically, I suppose that what is good, is what supports the well-being of conscious beings. (Think about it: does it make sense to ask whether maximizing well-being is good?) This conception of morality allows to give objective answers to moral questions in principle, because science can be used as a tool to describe what constitutes the well-being of concious beings and to understand the psychology and ecology of behaviours that cause more or less harm and happiness (though this doesn't mean it’s always easy or even possible to find answers in practice). This conception of morality also implies there can be wrong answers to moral questions. People their maps of reality can be vague, inaccurate and incoherent, which is to say that people - including me and you - can really value the wrong things for the wrong reasons. What is good, then, isn’t merely subjective or dependent on someone’s culture, but depends on facts about the well-being of conscious creatures within an ecological system. That being said, a universal conception of morality also doesn't require to be black-and-white. It doesn't require finding stringent moral truths that admit of no exceptions (dogmatism) or being able to always act consistently according to what is good (nirvana fallacy). I suppose that a scientific and critical inquiry of morality can help us to provide rational, open-ended and honest answers to moral questions and inform us to live the best life possible. Responsibility Responsibility can also be conceived as a natural phenomenon. I suppose responsibility is quite simply “the ability to respond”: when you question the things you do, you can give sensible reasons as to why you are doing what you are doing. Responsibility requires you to realize the consequences of what you do and the decisions you make. To me, responsibility really is an ability. As with other abilities, you can be(come) better or worse at it, and as with all abilities, responsibility is limited by all kinds of factors. More knowledge and awareness commits us to more responsibility, despite the notion that our responsibility is bounded by the limited information we have, the finite amount of time we have to process this information and the cognitive limitations of our minds. Considering morality, I think moral responsibility can be seen as the ability to act in ways that support the well-being of conscious beings (which includes your own well-being).

0 notes

Text

Request for Economic change

Economics can be described as the science that involves the coordination of efforts to accomplish certain ends (goals) by using available resources (means) within ecosystems both efficiently and effectively. In practice, the dominant economies in the Western world are focused on economic growth in terms of wealth and the pursuit of individual profit as ends rather than means. Because these ends lack intrinsic value or moral concern, these economies tend to behave as predatory systems, exploiting humans, animals and the environment as mere resources thereby causing harm as a consequence. Indeed, the world's mounting ecological problems and social inequalities are linked with the rampant economic growth in Western societies. The tragic irony is that an excessive desire for wealth also doesn't bring any fulfillment to those who pursue it. In principle, we could create economies that apply alternative conceptions of economic prosperity. Worthy economies focused on ends that are intrinsically valuable such as well-being and happiness. Harmonious economies that consider the intertwinedness of human, animal and ecological welfare. Caring economies that address global issues based on a shared responsibility. Sustainable economies that meet the needs of the present without compromising the needs of future generations. In practice, the seeds of these economies are already present. All we need to do is to nourish these seeds by our own actions if we want them to flourish, which is my request for economic change.

0 notes

Quote

Our language is an imperfect instrument created by ancient and ignorant men. It is an animistic language that invites us to talk about stability and constants, about similarities and normal and kinds, about magical transformations, quick cures, simple problems, and final solutions. Yet the world we try to symbolize with this language is a world of process, change, differences, dimensions, functions, relationships, growths, interactions, developing, learning, coping, complexity. And the mismatch of our ever-changing world and our relatively static language forms is part of our problem.

Wendell Johnson

0 notes

Video

youtube

Crash Course Economics: “You like to think of yourself as a rational person, right? Well, so do classical economists. Both you and the economists are wrong. Behavioral Economics takes into account the irrational behavior of real-life humans, and it’s fascinating: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dqxQ3E1bubI” I like to make the analogy with moral behaviour. People like to think they are responsible persons, but this is not necessarily the case. If one takes into account the harmful consequences of seemingly innocent behaviour of real-life humans, one can realize that responsibility is bounded by all kinds of factors (psychological, situational, etc.), which I find fascinating too.

0 notes

Quote

1. Do not feel absolutely certain of anything. 2. Do not think it worth while to proceed by concealing evidence, for the evidence is sure to come to light. 3. Never try to discourage thinking for you are sure to succeed. 4. When you meet with opposition, even if it should be from your husband or your children, endeavor to overcome it by argument and not by authority, for a victory dependent upon authority is unreal and illusory. 5. Have no respect for the authority of others, for there are always contrary authorities to be found. 6. Do not use power to suppress opinions you think pernicious, for if you do the opinions will suppress you. 7. Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric. 8. Find more pleasure in intelligent dissent that in passive agreement, for, if you value intelligence as you should, the former implies a deeper agreement than the latter. 9. Be scrupulously truthful, even if the truth is inconvenient, for it is more inconvenient when you try to conceal it. 10. Do not feel envious of the happiness of those who live in a fool’s paradise, for only a fool will think that it is happiness.

Bertrand Russell. (Title: The Ten Commandments that, as a teacher, I should wish to promulgate, might be set forth as follows – from: A Liberal Decalogue, Vol. 3: 1944-1969, pp. 71-2 )

383 notes

·

View notes

Text

What has science to say about morality?

I think the goal of science as a whole is to describe the nature of reality. Whether science can inform us about morality depends on someones notions of morality. If one believes morality doesn't have anything to do with reality; if one believes good and bad don't exist in the real world, than science can't inform us to make better choices in the real world. This also means that science can inform us to make better choices if our notions of morality do depend on real-world phenomenons. In my opinion, notions of good and bad only make sense if they relate to the well-being of sentient beings. Every and only a sentient being has an interest in avoiding aversive or unpleasant feelings (pain, disgust, sickness), and has an interest in experiencing pleasant feelings (happiness, the satisfaction of needs) (*). I think it's only reasonable to conceive unpleasant feelings as intrinsically bad, and pleasant feelings as intrinsically good. Therefore, the well-being of sentient beings in the real world is the center of my ethical concern. Science can be used as a tool to describe the well-being of sentient beings, to understand the psychology and ecology of behaviours that cause more or less harm and happiness, and to inform us to act morally responsible (**). An interesting video about what science can tell us about morality: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mm2Jrr0tRXk&feature=youtu.be&t=10m7s (*) The only sensible reason why one would choose to experience unpleasant feelings is to prevent more of them in the future, I suppose. (**) In a previous post, I conceived responsibility as the ability to give sensible reasons for your actions. Along the same lines, moral responsibility can be conceived as the ability to consider the well-being of sentient beings (including your own well-being) within your circle of influence. This depends upon self-control, empathy and reason.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are humans machines?

Somebody on Facebook asked the question whether humans can be compared with machines or whether humans can be conceived as some kind of biological machine. In my opinion, the human body as a biological machine can be an informative metaphore to better understand how it functions. However, when using this metaphore, I think it's important to point out that humans aren't just like any machine one probably thinks of when hearing the word 'machine'. When I think of a machine, I usually think of an automated soda machine, a dish washer, a computer ... These machines are man-made and typically perform a certain set of tasks to fulfill an intended purpose. Humans, on the other hand, aren't designed by other humans, but are ultimately the result of millions of years of evolution. Compared to a dish washer, the 'human machine' is incredibly more complex. It performs millions of tasks that don't have any intended purpose, but are functional adaptations promoting survival, cooperation and reproduction within certain environments. Furthermore, humans have conscious abilities, which things that are usually conceived as machines don't have. So yes, one can argue that humans are somewhat like machines, but they are not designed, incredibly complex and conscious.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thoughts on responsibility

Responsibility sounds like an important concept. Nevertheless, the concept is also pretty vague: people have radical different ideas of what responsibility means to them. I think the most reasonable and practical way to signify responsibility is as follows: Everything you do and every decision you make has consequences. Whether it’s how early you wake up, what things you consume in a day, which words you use to communicate … All these things have consequences. Being responsible means you realize that everything you do, and every decision you make has consequences. It means that you know why you do the things you do, and choose the things you choose. When you question the things you do, you have ‘the ability to respond’: you can give sensible reasons as to why you are doing what you are doing. Responsibility – to me – really is an ability. As with other abilities, you can be(come) better or worse at it, and as with all abilities, responsibility is bounded by reality. More knowledge and awareness commits us to more responsibility, despite the notion that our responsibility is bounded by the limited information we have, the finite amount of time we have to process this information and the cognitive limitations of our minds. - august 2014

1 note

·

View note

Text

Free will & Bounded responsibility

To put it generally, I believe we do the things we do because of continuous interactions between ourselves and our environment, which are both quite stable, yet ever-changing. Without the environment, there is no playground to act. Without ourselves, there is no act. Free will is oftentimes conceived as the idea that people ultimately cause their own choices, and therefore they are the ultimate source of their own responsibility. I believe this concept is fallacious. It artificially seperates ourselves from our environment, and assumes some kind of vague, magical "self" driving our behaviour. It obscures the fact that our choices are bounded by realities that aren't within our control. People don't cause their own choices "ultimately", but only to a limited extent, depending on the information present in their brains, and the environment with which they currently interact. If one believes in this magical concept of free will, it's easy to assume that a person who commited a horrible crime "could have acted otherwise", and is therefore ultimately responsible and deserving of blame and punishment. To me, this makes no sense. I believe acting responsibly really is an ability. In order to act responsibly, certain conditions must be met. An eagle isn't able to fly if it didn't learn it, nor if it's wings are cut. Similarly, acting horribly is obvious evidence of a lack of responsibility. Apparently, certain conditions weren't met to allow responsible behaviour. Bounded responsibility - the notion that responsibility is ultimately bounded by all kinds of realities beyond our control - forms a buffer against moralistic judging, allows to forgive others and oneself more easily and to focus on what's more important: to prevent more harmful irresponsible acts from happening (again) in the future. Blame and punishment should only be used if functional and needed to meet this goal, rather than being used as weapons to "fight evil".

0 notes