Watching some of the movies that played at the Vogue Theatre in Louisville, Kentucky between 1977 and 1998. A project by Andy Sturdevant.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

At the Vogue, twenty years (well, OK, nineteen years and ten months) after it closed. St. Matthews, Louisville, Ky., July 2018.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Tony de Peltrie” (1985)

The basics: Wikipedia

Opened: A landmark piece of computer animation, the Canadian short was part of the 19th Annual Tournee of Animation anthology that showed at the Vogue Theater in March and April of 1986.

Also on the bill: At least one Saturday in April, it was programmed in the 9:00 slot after Chris Marker’s Akira Kurosawa documentary A.K. and Woody Allen’s Sleeper, and before a midnight showing of Night of the Living Dead, which sounds to me like a very good eight-hour day at the movies. Otherwise, you could have had a less perfect day seeing it play after Haskell Wexler’s forgotten Nicaragua war movie Latino and the equally forgotten Gene Hackman/Ann-Margaret romantic drama Twice in a Lifetime.

What did the paper say? ★★★1/2 from the Courier-Journal film critic Dudley Saunders. Saunders described the Tournee as “a specialized event that shows signs of moving into the movie mainstream,” correctly presaging the renaissance in feature-length animation in the 1990s generally and Pixar specifically, whose Luxo, Jr. short was released that same year. Of Tony, Saunders singles it out as “one of the most technologically advanced,” and that it featured “some delightful music from Marie Bastien.” He then throws his hands up: "Computers were used in this Canadian entry. Don’t ask how.” Saunders was long-time film critic for the C-J’s afternoon counterpart, the Louisville Times, throughout the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s. In the late 1980s, he would co-found Louisville’s free alternative weekly, the Louisville Eccentric Observer.

What was I doing? I was six and hypothetically could have seen an unrated animation festival, though I'd have been a little bit too young to have fully appreciated it. Although, who knows, I’m sure I was watching four hours of cartoons a day at the time, so maybe my taste was really catholic.

How do I see it in 2018? It’s on YouTube.

youtube

A four-hour-a-day diet of cartoons was probably on the lower end for most of my peers. I grew up during what I believe is commonly known as the Garbage Age of Animation, which you can trace roughly from The Aristocrats in 1970 to The Little Mermaid (or The Simpsons) in 1989. The quantity of animation was high, and the quality was low. Those twenty years were a wasteland for Disney, and even though I have fond memories of a lot of those movies, like The Black Cauldron, they’re a pretty bleak bunch compared to what was sitting in those legendary Disney vaults, waiting patiently to be released on home video.

Other than low-quality Disney releases, the 1980s were highlighted mostly by the post-’70s crap was being churned out of the Hanna-Barbera laboratories. Either that, or nutrition-free Saturday morning toy commercials like The Smurfs and G.I. Joe. Of course there’s also Don Bluth, whose work is kind of brilliant, but whose odd feature-length movies seem very out-of-step with the times. Don Bluth movies seem now like baroque Disney alternatives for weird, dispossessed kids who didn’t yet realize they were weird and dispossessed. (Something like The Secret of NIMH is like Jodorowsky compared to, say, 101 Dalmatians.) Most of the bright spots of those years were produced under the patronage of the saint of 1980s suburbia, Steven Spielberg. An American Tale or Tiny Toon Adventures aren’t regarded today as auteurist masterpieces of animation (or are they?), but they were really smart and imaginative if you were nine years old. Still, the idea that cartoons might be sophisticated enough to be enjoyed by non-stoned adults was probably very alien concept in 1985.

In the midst of all of this, though, scattered throughout the world were a bunch of programmers and animators working out the next regime. Within ten years of Tony de Peltrie, Pixar’s Toy Story would be the first feature-length CGI animated movie, and within another ten years, traditional hand-drawn animation, at least for blockbuster commercial purposes, would be effectively dead. That went for both kids and their parents. Animation, like comic books, would take on a new sophistication and levels of respectability in the coming decades.

I love it when you read an old newspaper review with the benefit of hindsight, and find that the critic has gotten it right in predicting how things may play out in years to come. That’s why I was excited to read in Saunders’ review of the Tournee that he suspected animation as an artform was showing “signs of moving into the movie mainstream.” His sense of confusion (or wonder, or some combination) at the computer-generated aspects is charming in retrospect, too.

Tony de Peltrie is a landmark in computer-generated animation, but its lineage doesn’t really travel through the Pixar line at all (even though John Lassetter himself served on the award panel for the film festival where it was first shown, and predicted it’d be regarded as a landmark piece of animation). The children of the 1970s and ‘80s grew up to revere the golden era of Pixar movies as adults, and the general consensus is that not only are they great technical accomplishments, but works of great emotional resonance.

As much of an outlier as it makes me: I just don’t know. I haven’t really thought so. I think most Pixar movies are really, really sappy in the most obvious way possible. The oldest ones look to me as creaky as all those rotoscoped Ralph Bakshi cartoons of the ‘70s. Which is fine, technology is one thing -- most silent movies look pretty creaky, too -- but the underlying of armature of refined Disney sap that supports the whole structure strains to the point of collapse after a time or two.

Film critic Emily Yoshida said it best on Twitter: she noted, when Incredibles 2 came out, she’d recently re-watched the first Incredibles and was shocked at how crude it looked. "The technoligization of animation will not do individual works favors over time,” she wrote. “The wet hair effect in INCREDIBLES, which I remember everyone being so excited about, felt like holding a first generation iPod. Which is how these movies have trained people to watch them on a visual level...as technology.” There’s something here that I think Yoshida is alluding to about Pixar movies that is very Silicon Valley-ish in the way they’re consumed, almost as status symbols, or as luxury products. This is true nearly across all sectors of the tech industry now, but it’s particularly evident with animation.

One of my favorite movie events of the year is when the Landmark theaters here in Minneapolis play the Oscar-nominated animated shorts at the beginning of the year. Every year, it’s the same: you’ll get a collection of fascinating experiments from all over the world, some digitally rendered, some hand-drawn. They don’t always work, and some of them are really bad, but there’s always such a breadth of styles, emotions and narratives that I’m always engaged and delighted. They remind you that, in animation, you can do anything you want. You can go anywhere, try everything, show anything a person can imagine. Seeing the animated shorts every year, more than anything else, gets me so excited about what movies can be.

And then, in the middle of the program, there’s invariably some big gooey, sentimental mush from Pixar. Not all of them are bad, and some are quite nicely done, but for the most part, it’s cute anthropomorphized animals or objects or kids placed in cute, emotionally manipulative situations. I usually go refill my Diet Coke or take a bathroom break during the Pixar sequence.

Yeah, yeah, I know. What kind of monster hates Pixar?

I don’t hate Pixar, and I like most of the pre-Cars 2 features just fine. The best parts of Toy Story and Up and Wall-E are as good as people say they are. But when you take the reputation that Pixar has had for innovation and developing exciting new filmmaking technology in the past 25 years, and compare it to the reality, there’s an enormous gap. And it drives me nuts, because if this is supposed to be the best American animation has to offer in terms of innovation and emotional engagement, it's not very inspiring. Especially placed alongside the sorts of animated shorts that come out of independent studios elsewhere in the U.S., or Japan, or France, or Canada.

Which brings us to Tony de Peltrie, created in Montreal by four French-Canadian animators, and supported in part by the National Film Board of Canada, who would continue to nurture and support animation projects in Canada through the twenty-first century. A huge part of the enjoyment -- and for me, there was an enormous amount of enjoyment in watching Tony de Peltrie -- is seeing this entirely new way of telling stories and conveying images appear in front of you for the first time. Maybe it’s because I have clear memories of a world without contemporary CGI, but I still find this enormous sense of wonder in what’s happening as Tony is onscreen. I still remember very clearly seeing the early landmarks of computer-aided graphics, and being almost overwhelmed with a sense of awe -- Tron, Star Trek IV, Jurassic Park. Tony feels a bit like that, even after so many superior technical accomplishments that followed.

Tony de Peltrie doesn’t have much of a plot. A washed-up French-Canadian entertainer recounts his past glories as he sits at the piano and plays, and then slowly dissolves over a few minutes into an amorphous, impressionistic void. (Part of the joke, I think, is using such cutting-edge technology to tell the story of a white leather shoe-clad artist whose work has become very unfashionable by the 1980s.) It’s really just a monologue. The content could be conveyed using a live actor, or traditional hand-drawn animation.

But Tony looks so odd, just sitting on the edge of the Uncanny Valley, dangling those white leather shoes into the void. Part of the appeal is that, while Tony’s monologue is so human and delivered in such an off-the-cuff way, you’re appreciating the challenge of having the technology match the humanity. Tony’s chin and eyes and fingers are exaggerated, like a caricature, but there’s such a sense of warmth underneath the chilliness of the computer-rendered surfaces. Though it’s wistful and charming, you wouldn’t necessarily call it a landmark in storytelling -- again, it’s just a monologue, and not an unfamiliar one -- but it is a technological landmark in showing that the computer animation could be used to humane ends. It’d be just as easy to make Tony fly through space or kill robots or whatever else. But instead, you get an old, well-worn story that slowly eases out of the ordinary into the surreal, and happens so gradually you lose yourself in a sort of trance.

As Yoshida wrote, technoligization of animation doesn’t do individual works favors over time. To that end, something like Tony can’t be de-coupled from its impressive but outdated graphics. These landmarks tend to be more admired than watched -- to the extent that it’s remembered at all, it’s as a piece of technology, and not as a piece of craft or storytelling.

Still, Tony is the ancestor of every badly rendered straight-to-Netflix animated talking-animals feature cluttering up your queue, but he’s also the ancestor of any experiment that tries to apply computer-generated imagery to ways of storytelling. In that sense, he has as much in common with Emily in World of Tomorrow as he does with Boss Baby, a common ancestor to any computer-generated human-like figure with a story. When Tony dissolves into silver fragments at the end of the short, it’s as if those pieces flew out into the world, through the copper wires that connect the world’s animation studios and personal computers, and are now present everywhere. He’s like a ghost that haunts the present. I feel that watching it now, and I imagine audiences sitting at the Vogue in 1986 might have felt a stirring of something similar.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Bagdad Cafe” (1987)

The basics: Wiki | IMDb | Ebert

Opened: Percy Adlon’s Bavarian-housefrau-in-the-desert comedy Bagdad Cafe opened at the Vogue on Friday, September 16, 1988. It played once a day for one week, and as far as I can tell, never screened in Louisville again.

Also on the bill: During the six days it was showing in Louisville, it played with the 1987 Italian drama The Family. Both were shooed out the following week for Louis Malle’s acclaimed Au Revoir Les Enfants (and also for James Fox’s much less acclaimed White Mischief).

What did the paper say? ★★1/2 in the Courier-Journal, though this was another one outsourced to Janet Maslin at the New York Times. She said it was “too slow-paced to work as a comedy” and “simultaneously shapeless and pat,” but praised Marianne Sagebrecht’s performance as Jasmine, the German tourist who befriends C.C.H. Pounder’s Brenda, the harried owner of a roadside diner in the Mojave Desert.

What was I doing? I was eight years old. Even if I could’ve seen it (the nudity makes it unlikely), I’d have been bored. This is potentially something I could have rented in high school. But it didn’t even look like it was on cable that often, based on the listings.

youtube

Like Lair of the White Worm, which also screened for one week a few months later, considering Bagdad Cafe in the context of the Vogue Theater in 1988 is to consider some very low numbers. There’s no way that more than a handful of people saw this during the week. The lukewarm review in the C-J didn’t inspire much confidence (the local critic didn’t bother writing about it), there were no ads in the paper, and word-of-mouth only goes so far if it’s playing for one weekend. I’d be curious who turned out, but these are the sorts of the facts that are lost to historic record. Maybe some German ex-pats who saw anything playing in German. Percy Adlon didn’t have the devoted following that some of his West German colleagues like Fassbinder, Herzog and Wenders had, but perhaps there were a few film nerds who loved the New German Cinema and turned up out of curiosity. So for six screenings, maybe we’re looking at about a hundred people, max.

This is the kind of movie that falls by the wayside in the United States, although apparently it was enough of a hit in Germany that the real Bagdad Cafe in California, where the movie was filmed, remains a tourist destination for Germans to this day. It’s funny in a low-key way, and it’s got the sort of aimless ‘80s indie weirdness that feels charming viewed thirty years later. Fuzzy aimlessness onscreen was in a transitional state in the ‘80s, I think: less grim or politically fraught than the ‘70s version (a la Altman), and not quite as self-aware or studied as the ‘90s version (a la Kevin Smith).

The movie begins with a series of low, flashy shots and untranslated German dialogue between Jasmine and her soon-to-be former husband, who abandons her in the desert after an argument. It’s stylized to the point where it seems almost like a hip trailer. It’s kind of hard to say what Adlon had in mind for the movie, as far as whether he’s making a cool hipster curiosity or a sweet and cuddly tale of friendship and love. His MTV-influenced camerawork and minimalist dialogue would seem to indicate the former, while the title track is a bubbly harmonica ballad that suggests the latter.

It’s not really a movie with any big ideas, which is kind of refreshing. Adlon and his partner Eleonore, who co-wrote it, seems to regard the oddball small-town Southwestern community as a type of racially integrated paradise inhabited by outcasts and eccentrics, African-American, Hispanic and Native. The characters’ primary problem is not poverty, lack of social services or racism, but a sort of good-natured aimlessness that can be set right by a little bit of stoic German know-how. Jasmine and Brenda are at loggerheads at the beginning -- Jasmine, a provincial German hick, has a weird, racist fantasy about being boiled in a stew initially (!), and Brenda is pretty provincial herself, instantly suspicious enough of this German woman to call the local sheriff (!!).

Eventually, though, they build a relationship over time that blossoms into a professional partnership. Jasmine tidies everything up, and more importantly, picks up some magic tricks from a kit left in her husband’s suitcase. By the end, the diner has a floor show that’s made it a destination for truckers and tourists. The warmth and eccentricity reminds me much less of a brutal quasi-nihilist like Fassbinder than someone like Jonathan Demme. Proto-Andersonian character-focused whimsy was in ample supply during the period, though, so I don’t know if this one made much of an impression nationally (and certainly not locally). Not all of these could become cult films, I suppose.

A lot of German filmmakers seemed to be fascinated by the United States in the 1970s and ‘80s, like Wim Wenders, whose Paris, Texas deals with some of these ideas a little bit more effectively. I wonder how a reversed Bagdad Cafe would play today, now that the roles have partially reversed from the 1980s: United States is a tired, decaying superpower in decline, and Germany often seems to be the last best hope of democracy. What would a displaced Texan tourist bring to a community of people in Berlin or Frankfurt or small-town Bavaria? Not in the familiar way of a free-spirited American liberating a bunch of uptight Germans (though, to some extent, that’s what happens here: Jasmine is able to let her inner magician/cabaret star shine in this free-spirited environment).

Rather, made from a German perspective, what would such a tourist learn from the community? Would she toss aside her stubborn, contrarian individualism and embrace the communitarian ethos of an efficient and cosmopolitan society? Would something about her sense of independence, in fact, assist in the communitarian German project? It’s Jasmine’s firm but humanitarian sense of order and discipline that liberates the people of the Bagdad Cafe from their own ennui and frustration. Her Germanness allows the Americans to be all the more American: happy, successful, idiosyncratic, fun-loving, harmonious. Could Americanness allow a German community to become more German?

Who knows what anyone seeing Bagdad Cafe at the Vogue thought about any of this. Socio-cultural considerations, aside, there was such a rich vein of this kind of movie in the 1980s, as I noted before. My guess is that, compared to other charming culture-clash character studies like Local Hero or Down by Law, Bagdad Cafe got lost in the shuffle. The fact that any small, independent movie was able to find any kind of audience nationally when in many cases it showed in a city for just a single week is sort of miraculous.

0 notes

Text

“Stop Making Sense” (1984)

The basics: Wiki | IMDb | TVTropes

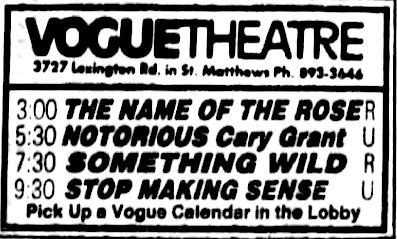

Opened: Jonathan Demme and David Byrne’s Talking Heads concert film opened the second week of March 1985. It ran for a few weeks, and by early June was showing at Village 8, the local second-run theater. It was revived at The Vogue in July, and ran a few times a month through 1986 and 1987, usually as the second-to-last or last show of the day.

Also on the bill: Opening weekend, it shared a very unlikely bill with the slow-burning 1975 Australian film Picnic at Hanging Rock. It also shared some more tonally appropriate bills with Buckaroo Banzai, Amadeus, Fellini Satyricon and another Australian cult favorite, Bliss. A few times, of course, it was inevitably programmed before the monthly midnight screening of Rocky Horror.

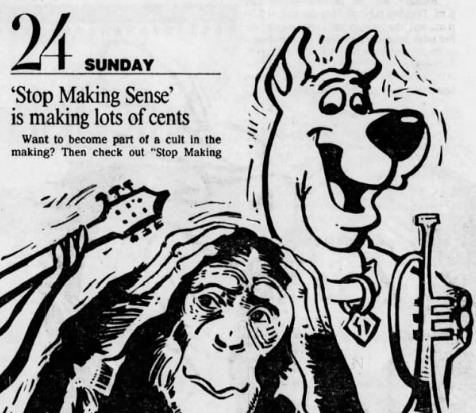

What did the paper say? Given its status in years since as the great rock concert movie of that (and any) era, there wasn’t much coverage at the time. The Courier-Journal’s regular film and theater critic from the late 1940s through the early 1990s, William Mootz, didn’t appear to see it. Janet Maslin’s glowing New York Times review was run instead, as was common practice for smaller movies. Vince Staten, the vaguely curmudgeonly but always insightful TV critic of the 1980s, wrote a few years later when it came out on VHS that "quite a few people, myself included, thought it was the best rock-concert movie ever made.” In 1987, towards the end of its run at The Vogue, a weekend roundup in the paper’s Saturday edition highlighted it, calling it "a cult in the making" that was “building a faithful following in its repeated engagements at the Vogue Theatre.” The headline was “’Stop Making Sense’ is making lots of cents.”

What was I doing? I was between six and eight years old. It was unrated, so I certainly could have seen it, though neither of my parents were Talking Heads fans, and I don’t think it would have occurred to them to take me -- this is the kind of thing my cool aunt would have considered taking me to see. Maybe I am giving myself more credit than I deserve, but I think I would have liked parts of it quite a lot.

In a mid-sized town like Louisville in the 1980s, I imagine fringe culture tended to consolidate itself into small, overlapping groups. Bookstores, bars, music venues, video stores, coffee shops and art galleries serving the same audiences all overlapped in their programming to some extent.

The Vogue, in addition to showing the movies we’re talking about here, was also an occasional music venue. Its musical programming served a roughly parallel function to its cinematic programming: it was an outlet what used to be called “alternative” culture. A number of Louisville’ earliest punk and new wave shows, in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, happened there.

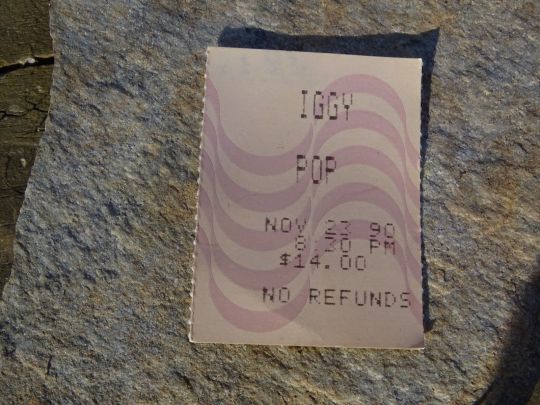

In fact, on that note, I have an eBay alert set up for “vogue louisville” so I can grab any Vogue-related memorabilia that comes through. Almost nothing does, though recently there’s been someone trying to unload a ticket stub for an Iggy Pop show presented there in partnership with the Kentucky Center for the Arts in 1990. The sort of person who might go see Iggy would also likely be there for the showings that week, which included Pump Up the Volume and Pink Floyd The Wall. Neither of those were exactly countercultural circa 1990, but were certainly adjacent. (Incidentally, I’m a little tempted to buy that Iggy ticket, but it doesn’t even have the name of the Vogue printed on it, so it doesn’t seem like it’s really worth it for my purposes. Still, there it is below.)

Jonathan Demme’s Stop Making Sense played the Vogue for about two years. Though that was a lot longer than most rock movies, it was far less than, for example, Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains the Same, which played for ten years, or the aforementioned Pink Floyd The Wall, which showed regularly for almost fifteen, right up until a year before it closed. This tells us that while the Vogue catered regularly to a new wave crowd, their economic bread and butter was either aging boomers or stoned college kids who remained in an oblivious dope haze throughout the events of the 1980s (or possibly both).

But a few times a month for two years indicates there was a healthy interest in Stop Making Sense among a fairly sizable portion of Louisville’s young cultural elite. There were a lot of weirdo bands in Louisville in the mid-1980s, loosely aligned with punk but a little artier, and I wonder how of them were in attendance. Once again, this is one of the big problems with this experiment: watching a lot of these movies on a streaming service on a TV all by myself is so unlike seeing it projected on film in a communal setting with a roomful of people that it barely qualifies as the same experience. It’s like trying to write about having a dinner at the French Laundry by eating a Trader Joe’s frozen quiche lorraine over the sink in your kitchen. Koyaanisqatsi loses a lot in this format, and Stop Making Sense may lose even more.

Koyaanisqatsi, which was also on the midnight movie circuit about the same time, is a fully immersive experience, like Stop Making Sense. Demme’s movie, though, goes a step beyond immersion by inviting active participation. It’s shot from the perspective of the audience, with no reaction shots or backstage interviews, and since the audio was recorded digitally, it was crystal-clear, or as crystal-clear as the P.A. allowed at the Vogue. Probably the sound and sights were, in some way, superior to those you might have seen at that Iggy Pop show live in person. Most of the reports from the time -- not in Louisville specifically, but in many places -- make note of people dancing in the aisles. I can imagine it must have been a similar scene at the Vogue.

As a director, I didn’t give any thought Jonathan Demme up until a few years ago. I’d seen Silence of the Lambs, and liked it OK, and although I adored Swimming to Cambodia, I thought that had more to do with Spalding Gray than Jonathan Demme. In a stirring reminder, though, that the internet can still cough up truly remarkable documents that change the way you see the world, I stumbled across this Jacob T. Swinney supercut from 2015. I remember opening it, and scoffing to myself, “oh, so Jonathan Demme is like an auteur now?”

Obviously I was way, way off-base. Three-and-a-half minutes later, the video had made a total convert of me. The way those faces looked at you -- clearly there was something here. I rented all of them over the course of a few weeks, through his early and middle period, from Melvin and Howard through Married to the Mob. I came away with the sensation of falling in love, partially with way of making movies but also with a whole worldview. Demme’s movies find a way to be incredible stylish assemblages of the best parts of North American culture (all accompanied by incredible soundtracks), and also turns its attention to oddballs, misfits and outcasts with a loving gaze that manages to be both amused and compassionate.

Stop Making Sense does all of these things. David Byrne is not warm, exactly, but his arch sense of humor is endearing, and of course he’s one of the great eccentrics of late 20th century American culture. And he’s surrounded by a gang of musicians that seem like they’re right of out of a Demme movie, like the house party at the end of Swing Shift or the Miami hotel pool in Married to the Mob: Chris Frantz in funny-dad mode with a very un-rock-star polo shirt, Bernie Worrell mugging at the camera, Tina Weymouth looking cool in a succession of power suits, Lynn Mabry and Ednah Holt providing synchronized commentary throughout.

It’s only at the end that Demme, as if he’s been teasing you by withholding them, allows some audience shots to sneak in. They look like the sorts of sweet, goony people you’d hope to meet at a Talking Heads show. After every Demme movie, there’s a sense that you, too, could be part of a global community of weirdos who take care of one another.

I can tell you from experience that being weird in a place like Louisville, a town that can be both rigidly conservative and indulgent of eccentricity, could be sort of a lonely experience. It was also the sort of place where there were enough of you out there that you usually found each other somehow. I hope a few of the members of that Demmian-Byrnian community, all out at the Vogue on a Saturday night dancing in the aisles, caught a glimpse of one another when the lights came on.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Lair of the White Worm” (1988)

The basics: Wiki | IMDb | TVTropes

Opened: Ken Russell’s Bram Stoker adaptation opened in Louisville on the weekend of January 13, 1989 at the Vogue, and ran for one week. It played for a handful of weekend late-night screenings that March.

Also on the bill: The week Lair of the White Worm played at The Vogue, it usually showed between two documentaries. The 5:30 show was China Run, a now-mostly forgotten story of a Kentucky man named Stan Cotrell who ran 2,000 miles across China in the 1980s (Cottrell made some in-person appearances at the theater during the week). At 9:30, they showed Big Time, a Tom Waits project from the period when it looked as if he was going to have a parallel career as an indie film actor. There’s maybe a little bit of audience crossover for White Worm and Big Time, but generally, between two indie documentaries isn’t a great place for such an odd little genre movie to be stuck.

What did the paper say? ★★1/2 from Courier-Journal film critic Roger Fristoe. A lot of times, with movies like this that only played for a week and didn’t get a wide release, the C-J would just reprint Janet Maslin’s review from the New York Times, or a wire review from someone like Jack Garner. For whatever reason, though, Roger took it upon himself to drive down to the Vogue and see the movie in person. He thought it was “more often than not, highly entertaining” with “modern kinkiness and hallucinatory effects that suggest a nightmare version of MTV.” If anything, he found it “a bit talky,” with “grainy” and cheap-looking special effects.

What was I doing? I was eight years old, and there was way too much nudity for me to have seen in the theaters or anywhere else. It played regularly on Cinemax and Bravo in the early 1990s; perhaps I’m misremembering this, but I have a foggy memory that Amanda Donohoe had kind of a cult following in my middle school because of her extremely nude performance in this movie.

How did I watch it in 2018? Amazon Prime.

Maybe if someone other than Ken Russell had directed Lair of the White Worm, it’d be more of a cult movie than it is. Russell’s filmography is so full of over-the-top cult movies that this one gets lost in the shuffle -- it’s pretty minor in the canon, compared to weirdo classics like Tommy or Altered States or Women in Love. But then again, nobody but Ken Russell could have directed this. It’s got all of the Ken Russell hallmarks: the crucifixes, the nudity, the blood, the low-budget special effects, the nineteenth century setting. It’s a Bram Stoker adaptation, though it apparently doesn't have much to do with the novel, starting with the fact that it takes places in the 1980s and none of the characters have the same names. (Although there’s a monologue on the Anglo-Saxon origin of the word “worm” that comes directly from the Stoker text.)

In short, Hugh Grant, the wealthy descendent of a dragon slayer, and Peter Capaldi, an archeologist from Scotland, are dating Sammi Davis and Cathy Oxenberg, a pair of sisters whose parents have died under mysterious circumstances recently. It seems connected to a myth of a white worm that lives in a hillside. Amanda Donohoe, a chic member of the international jetset that lives alone in a castle, seems to be connected somehow. Blood, nudity, flashbacks, vampirism and snakes ensue. A Boy Scout gets his dick bitten off. Hugh Grant chops a vampire in half. Amanda Donohoe is hypnotized by the sound of Peter Capaldi playing bagpipes and does a snake dance out of a basket she is sleeping in. (All that stuff is in the original theatrical trailer, actually.)

youtube

So it came and went at The Vogue in the space a week, though it had a healthy afterlife on cable TV and, presumably, VHS. The economics of the pre- and early home video eras are interesting when you look at the hard numbers: If it only played eight or nine times at The Vogue, how many people could possibly have seen it? The Vogue had 800 seats, but with maybe the exception of a few weekend nights, it’s hard to imagine more than a few dozen people at most for each screening. Diehards who saw everything The Vogue played, maybe, or committed Anglophiles, or weirdos who saw the trailer or read Peter Travers’ review in People and were really into the idea of a sexy snake horror movie. Maybe 200 people saw it in the whole state of Kentucky in all of 1989. Who of those thought about it much afterwards? It must have seemed like a hazy memory.

In fact, part of the enjoyment of seeing Lair of the White Worm today would have been completely absent in 1988. It was an early major motion picture role for each of its three stars. Amanda Donohoe would later appear on a lot of quality TV and in a few art house movie roles. Of course Hugh Grant (who is 28 here but looks like a college senior) and Peter Capaldi (who is 30 but looks like a college sophomore) would become major stars. There’s at least 200 Louisvillians who later saw Four Weddings and a Funeral or The Thick of It and thought, huh, he looks familiar, wait, he was in the Ken Russell white worm movie, wasn’t he? In fact, the reason I chose this movie out of the dozens that also played at The Vogue in 1988 is that, all these years later, I recall my high school social studies teacher mentioning it in the mid-1990s. Clearly he was one of those 200.

This is the kind of movie that, in some ways, plays best to a mostly empty house, with maybe a handful of other people. A few other voices to join with in laughter when appropriate, but largely silent elsewhere in the theater. Seeing it on a Tuesday night in March is close to ideal. It has such a jerky, dreamlike quality that I can imagine walking out of the theater, and exchanging glances with the one or two other people straggling out: did I really just see that? My girlfriend wandered into the room during the scene where one of the sisters has a very, very sudden hallucination of Jesus Christ on the cross being strangled by a white worm while Romans centurions slaughter a bunch of nuns and thunder and lightning and psychedelic green screen effects are flashing in the background. She could only muster a dazed “what the fuuuuuck” and backed out of the room.

Ken Russell had enough influence to be able to make whatever kind of weirdo movie he wanted in the late 1980s, provided he made it entertaining and kept it under budget, and Lair of the White Worm meets those criteria a couple of times over. Roger Fristoe, in his review for the local paper, wasn’t wrong when he suggested the special effects looked like they were done cheaply on video. No doubt this thing came in plenty under budget. It’s pretty crappy-looking in most parts.

It’s also kind of fun, though. I didn’t grow up with the Hammer horror movies, which is what Russell was calling back to, but I’ve seen enough of them later in life to appreciate the parallels. Even without that frame of reference, it feels like it draws equally on Satanic panic and MTV quick-cuts, making it undeniably an artifact of the 1980s. However, it’s also clearly a product of the era of psychedelic sleaze that Russell came up in, where compensating for the small budget meant ramping up both the psychedelia and the sleaze in equal measures. As funny as it seems, in 1988, Russell was only as far along in his directorial career as David O. Russell or Kevin Smith are today. He’d been around for awhile, but was by no means an elder statesman. He was still a vaguely disreputable eccentric who could work cheap and fast.

He assembled a brilliant young cast, even if they occasionally look like they’re being held hostage. Hugh Grant and Peter Capaldi are already playing Hugh Grant and Peter Capaldi: the latter is posh and diffident and charming, and the latter is irascible and intense and vaguely Whovian. (His character is also Scottish, and in case this wasn’t clear, he’s named “Angus Flint” and wears a kilt and happens to have brought some bagpipes with him while on an archeological trip.)

So Hugh and Peter are great, but it’s Amanda Donohoe who stands out.

Lady Sylvia Marsh is one of the nuttiest, most self-aware performances of the era, in an era with no shortage of nutty, self-aware performances. Lady Sylvia is a wealthy, sex-crazed vampire-yuppie (and the costume design is very on point here), but she is also an immortal snake-woman that hates bagpipes and Christianity, and wears a snake-shaped strap-on in rituals enacted to pay worship an enormous white worm that lives in a whole in the side of a hill. She manages to embody all of those things. It’s the kind of amazing performance you can really only do in a weird, inexpensive genre movie where the stakes aren’t that high, and where you’re relatively free to pursue the role in whatever way you see fit. She pursues it with an intensity that seems hard to fathom.

Perhaps that’s just as well, though. A movie like this is maybe best shared as a secret with a select few, and I am sure that’s something The Vogue must have helped foster among a certain subset of local moviegoers. One of the most appealing things about The Vogue must have been that it, like the white worm, seemed like an ancient, secret cult in a dank lair in the east end of Louisville.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“A Boy and His Dog” (1975)

The basics: Wiki | IMDb | TVTropes

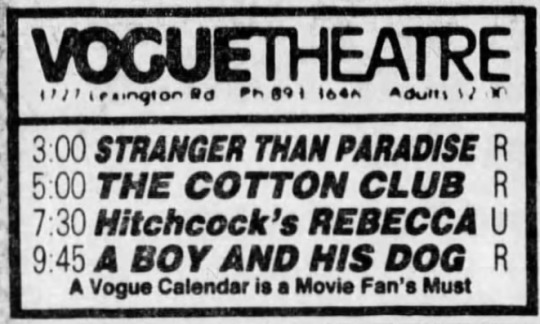

Opened: Originally opened in Louisville in 1976 at the Uptown Cinema in the Highlands, and went into wide release in the summer of 1977. (Alvy Moore, the producer, came to town in 1976 to personally promote it.) It played regularly at The Vogue from the end of 1977 through 1987, usually as the last show of the evening.

Also on the bill: As with many of these ‘80s-era cult films, it played with all sorts of movies over the ten years it was in regular rotation. On the last bill at The Vogue I can find, from July 1987, it played at 11:30 on Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights, preceded by Room with a View (5:00), Impure Thoughts (7:30) and Angel Heart (9:30).

What did the paper say? Courier-Journal contributing critic Gregg Swem (grandson of the noted historian) filed an unstarred but unambiguously negative review of the movie before it opened in March 1976. Swem described it as, among other things, “poor quality,” “tiresome,” “silly and sophomoric,” with “little to offer,” “very little suspense and futuristic tone,” and “shoddy acting and an elementary script.”

What was I doing? I remember seeing the poster in the newspaper and the alt-weekly for this all the time as a kid, and later, in the video store. I have a vague recollection of wanting to go see it. Who doesn’t love a boy and a dog, going on some kind of adventure? Plus, it’s one of those designs that looks really cool on the cover of a VHS tape. I’m sure I wasn’t the only kid to think this in the mid-1980s. It’s just as well I never saw it.

How did I watch it in 2018? Amazon Prime.

The cliches about the unfathomable nature of the past are mostly true. It’s a weird, fucked-up place and if you didn’t live there, it’s hard to figure out what people were thinking.

A Boy and His Dog was something of a cult film in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, both in Louisville and elsewhere. It has the markings of a cult movie: a novel conceit, a strong visual identity executed with almost no budget, and a handful of quotable dialogue. The novel conceit here is that one of the main characters is a talking dog (OK, actually he’s telepathic, like Garfield, but the overall effect is that he can talk), and he has a fussy, smartass human voice that sounds like a 1960s sitcom dad. Good so far.

Watching it from a contemporary perspective, though, any aspects of the movie that might have seemed novel or appealing are immediately improved upon by other sci-fi movies that came along immediately after. Compared to Mad Max, for example? Not even close: Mad Max undertake a similarly ambitious feat of worldbuilding on an equally tiny budget, and ends up being both funnier and more exciting to watch. Dawn of the Dead? Not only is it more politically astute, but it’s also less clunky. Even Zardoz, which is undeniably a really stupid movie, seems more fun, if just for Sean Connery’s two-piece battle thong. A Boy and His Dog, by comparison, just seems crass and cheaply made.

If you extend the comparisons into the 1980s, when the movie played most often, it seems incomprehensible that either a theatrical programmer or the paying public would want to sit through this when they could choose from Escape From New York, The Thing, The Quiet Earth or The Terminator.

Part of this is me bringing my gossamer snowflake post-millennial sensibilities to the movie, though: my primary distaste for it has a lot to do with the fact that it’s so nakedly misogynist, a stance with is crystallized in the fact that the primary character is Don Johnson’s teen rapist. A lot of 1970s movies are a little rapey, but at least with many of them, the rapey qualities are not presented as charming or funny, or at the very least constitute severe character flaws.

So, in the interest of full disclosure, I turned it off after about half an hour because I couldn’t stand spending any more time with Don Johnson’s character. The ending, which I didn’t see but which I didn’t mind spoiling after the fact, confirmed my suspicions that the movie was on the wrong track from the beginning. It’s easy enough to find out what happens (there’s a pretty well-known last line the dog delivers). Apparently Harlan Ellison, author of the book the movie was based on, hated the ending himself. So maybe I’m in good company.

It’s easy enough to turn off a movie at home -- too easy, sometimes -- but I doubt I’d have stuck around for this in the theater. I’ve never been shy about walking out of movies if I’m bored, offended or disgusted. You gamble the price of a movie ticket on these types of things, and they don’t always pan out. The fact that this one didn’t outlive the late ‘80s on the Vogue’s cult circuit suggests that the culture of midnight movies had walked out by then, too. Whether that’s due to improving taste on the part of Gen-Xers or just a wider variety of post-apocalyptic cult movies to choose from isn’t clear to me, but I’d guess it’s maybe a little bit of both. Look at the Vogue at the top of the post, from 1984: Stranger Than Paradise and A Boy and His Dog, on the same bill. Only one of those two movies has aged particularly gracefully; Jarmusch’s movie is as much a product of its time as A Boy and His Dog, and in its own way equally dated, but its understated, smart-ass hipster sensibilities still feel vaguely contemporary. The idea that both movies existed in the same cultural space seems kind of baffling.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Koyaanisqatsi” (1983)

Opened: Opened in Louisville on Thursday, February 16, 1984 at the Vogue, with the premiere serving also as a fundraiser for the classical public radio station WUOL. I don’t remember the classical station ever playing Philip Glass, but maybe they were saving all the Glass and Steven Reich and Meredith Monk for after my bedtime.

How often did they show it? Koyaanisqatsi played once or twice a year at the Vogue from 1986 through 1989, usually on the weekends as the last show on the bill. The last screening was in the fall of 1992, where it played at 9:30 on a Tuesday night bill after Gregg Araki’s The Living End.

Also on the bill: Later in the ‘80s, it served as a 9:30 lead-in for midnight screenings of Rocky Horror and Pink Floyd The Wall. One particularly intriguing double bill was on June 3, 1987, where it played after another environmentally minded film highlighting the grim, often comic absurdity of life in late 20th century urban America: Star Trek IV.

What did the paper say? Courier-Journal film critic Roger Fristoe was pretty cool on the film, calling it “occasionally euphoric” and “impressive,” but also concluding that it has “only one point to make, and makes it with such shrill insistence that it begins to seem slightly hysterical.” It seemed more successful, he thought, as “a visual experience than as a philosophical argument.” Fristoe added, slyly, “Cities have their good points, too, and not everyone wants to live in Monument Valley.”

What was I doing? I was four years old when it opened, and it screened just before my prime take-your-kids-to-see-an-unrated-art-movie-with-no-nudity-drugs-or-violence years. I don’t think I’d seen it before, but if I did, it was most likely on PBS, where it played regularly throughout the 1980s.

How did I watch it in 2017? Amazon Prime.

The conventional wisdom on Koyaanisqatsi, both at the dawn of the home video era as today, is that you are definitely not supposed to see it on a small screen. It’s meant to be seen on a large screen and become completely immersed within. Part of the word-of-mouth about this odd little documentary -- 90 minutes of time-lapsed photography of natural and human-made landscapes, with no dialogue or actors, accompanied by a Phillip Glass score invariably but accurately described as “mesmerizing” -- is that it was a full-scale experience that people wandered out of, dazed and awestruck, and saw the grandeur of their surroundings in a new and maybe consciousness-altering way. I believe that is probably true.

Of course, I feel a little relief knowing that Koyaanisqatsi’s afterlife has involved quite a few small screens. if you were going to see Koyaanisqatsi in Louisville in the 1980s, you’d maybe see it at the Vogue, but more likely you’d see it on Channel 15, the local public broadcasting station. It played at the Vogue a few times, but showed up on PBS The Great Performances just as often in 1985 and ‘86. In 1998, Vince Staten, the Courtier Journal’s full-time media critic (an occupation that no longer exists, as far as mid-sized local papers are concerned) wrote that Koyaanisqatsi was the number-one best-selling used video on “the internet.” It was actually the number-one selling secondhand tape on reel.com, an early online store for videos that was eventually acquired by Hollywood Video.

Staten found the popularity of Koyaanisqatsi on that platform somewhat baffling, given the movie’s artsy reputation. In fact, he was even more dismissive than his erstwhile colleague Roger Fristoe in his assessment: he called it a “new age mood piece.” This proves that people on the internet, Staten continued, “are stranger even than the people who read this column.” All of this is funny for a variety of reasons, but funniest of all is imagining a time when humanity could be divvy’d up into people on the internet and people off the internet.

(A quick parenthetical: twenty years later, there are 30 used DVD copies of Koyaanisqatsi currently for sale on eBay. Compare that to 181 used copies of the top-grossing movie of 1983, Return of the Jedi, and 190 of the second-highest title, Terms of Endearment. The secondhand market has righted itself again and realigned with popular tastes, it looks like. Staten’s point is well-taken: the internet really was mostly for weirdos and niche obsessives in the 1990s.)

So while I missed out on a big part of the experience by watching Koyaanisqatsi in my living room on a Sunday night, I was going to miss out on a big part of the experience any way I decided to watch it. The techniques used in Koyaanisqatsi are so ubiquitous now, that it’s one of those movies like Citizen Kane or The Matrix where, no matter how much you enjoy it, the impact it had on its original viewers can’t quite be replicated. The idea of minimalist music over time-lapse photography is so ingrained in the advertising language of the late 20th and early 21st centuries that some brilliant person recently re-assembled the original trailer using only watermarked stock footage. Maybe someone like Adam Curtis is the logical heir of this style, but so are tens of thousands of anonymous creative directors making credit card and pharmaceutical commercials.

One of the difficult things for me about watching movies from the 1980s and 1990s that aspire to some sort of social critique -- and Koyaanisqatsi sort of fits in this category, though if it does have a political or social message, it’s nuanced and open to personal interpretation -- is that, having the benefit of perfect clarity of hindsight, I lose a lot of patience with the messaging. The years from 2001 to 2016 present any number of sociopolitical trump cards, including the biggest and best metaphorical trump card imaginable, Donald Trump himself. “You bozos think things are so bad in 1983,” I grumble to the filmmakers of that period. “Well, just you wait. After everything that happens between the World Trade Center attacks and the 2016 election, you’re going to be begging for the early 1980s.”

That’s really not accurate, nor it it fair; there was plenty in the Reagan years to feel grim about. But there was a little itch of that watching Koyaanisqatsi. It certainly isn’t really a polemic, and in fact, the filmmakers wanted it to be completely untitled, like a painting or a poem, so as not to tip the scales in terms of how people interpreted it. At a late date, though, they were compelled by the distributors to give it a proper name, and they chose Koyaanisqatsi, which in the Hopi language means “life out of balance.” There’s any number of ways to reconcile how the images on the screen reflect an idea of how life might be out of balance, but it certainly does give the whole exercise a disapproving quality. Fristoe, in his Courier Journal review from 1983, alludes to that: sure, industry and progress are dirty and dehumanizing, but we can’t all live in Monument Valley, right?

However, there is something kind of prophetic about Koyaanisqatsi. The middle passage of buildings collapsing into towers of smoke and dust is impossible to watch without thinking of the World Trade Center (in a way that really gets into Adam Curtis territory), and the general idea that life is increasing in speed and complexity is a familiar one. My own hindsight-addled disapproving tone -- “gee, they think all this technology is so bad, well just wait” -- was undercut pretty quickly by the fact that the movie isn’t really smug or judgmental about how that technology pushes the speed of daily life to something approaching mania. Instead, it seems to both reflect and empathically anticipate the increased freneticism to come. While the title suggests there’s a little bit of a value judgment involved, there’s also a sense of excitement at being a witness to the thrill of it all.

Even though the frenetic pace of the way the images wash over you feels very genuine to the experience of the twenty-first century, there’s something resolutely twentieth century about the whole experience that now almost seems quaint. It moves along quickly, but it lingers, too. It’s an hour-and-a-half commitment that is full of callbacks and parallels and distinct movements. It’s like a feeling of being on a threshold, pausing before taking a leap off of a diving board, and enjoying the moment of quiet before you plunge into whatever is below. The 1983 of Koyaanisqatsi seems forever ago, but there’s a sense that an era that hasn’t yet ended is beginning, and this is one of the first times it’s been expressed in a way that still feels familiar.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Big Chill” (1983)

Opened: First opened in Louisville in October 1983 at Showcase Cinemas and a few of the other first-run multiplexes.

How often did they show it? The Big Chill played every few months at The Vogue from the tail end of its first theatrical run in 1984 through mid-1987.

Also on the bill: A typical bill from 1987 is Prick Up Your Ears at 7:30 (then a first-run movie), The Big Chill at 9:30, and Creature from the Black Lagoon at 11:30.

What did the paper say? ★★★1/2 from Courier-Journal film critic Roger Fristoe when it opened in 1983. He called it a “funny, caring film” with “a brilliant ensemble performance of eight of the best young actors in films.”

What was I doing? I was four years old when it opened, and seven and eight when it played at The Vogue. There’s no plausible scenario under which I’d have seen it then, and I’d never seen it before now.

How did I watch it in 2017? Amazon Prime.

The fact that The Big Chill was a reliable presence at The Vogue few years after its release, even taking precedence over first-run features like Prick Up Your Ears, might give us a clue to the theater’s target demographic: boomers. From 1977 to 1998, the years we’re cataloging, I am certain the most reliable patrons of the theater were probably people a lot like the characters in The Big Chill. Mostly children of the Vietnam era, well-educated, white, middle class professionals with some sense of idealism, curdled or not, who’d probably been introduced to international and independent film on college campuses of the ‘60s and ‘70s at places like the University of Michigan, the characters’ alma mater. My guess is a lot of people going into see The Big Chill for the second or maybe third time in 1986 and ‘87 were seeing a version of themselves onscreen.

This was the first time I’d seen it, though its reputation precedes it: a group of college friends reunite for a weekend after their friend kills himself, and come to terms with what they’ve become, and what they mean to each other. I’ve known for a long time it was a major generational landmark for boomers, in terms of both the depiction of the decline and fall of the ‘60s generation, and for the ensemble of actors. That opening scene, scored to “I Heard it Through the Grapevine,” is an absurd roll call of character actor talent that just keeps coming: Kline! Close! Goldblum! Hurt! Berenger! And they all look so young!

I have some Gen-X’r friends that are mildly contemptuous of the movie, in the way people tend to be contemptuous of the mass culture their adult siblings might have been into when they were surly teenagers (like in the way, for example, I think the tentpole X’er Cameron Crowe movies are kind of stupid). I don’t necessarily have the same preconceptions about The Big Chill, as I came almost exactly one generation after the filmmakers. The first scene in movie has Kevin Kline bathing his young son, who’s played by director Lawrence Kasdan’s real-life son Jon. Lawrence Kasdan is about the same age as my parents, and I am almost exactly the same age as Jon. He was born in September 1979, and I was born in November.

Even more than the cast, the movie is maybe best-known for its soundtrack, a cornucopia of what would later be known as oldies, late 1960s superhits like “I Heard it Through the Grapevine” and “Bad Moon Rising.” It’s impossible to imagine a world where Motown songs weren’t totally ubiquitous, but that seems to have been more or less the case in the early 1980s. The first oldies station in Louisville, 103.1 WRKA, launched in 1989, when I was nine years old, and my understanding is that the success of The Big Chill soundtrack kicked off a resurgence in interest in ‘60s music, in the same way American Graffiti kicked off a mania for ‘50s music ten years earlier. For the five or six years following, oldies were the soundtrack of everyday life around the house and in the car, and every one of the songs in heaviest rotation were on that soundtrack.

In fact, in his original, glowing review of the movie in 1983, Courier-Journal movie critic Roger Fristoe’s sole complaint is "the cliche use of pop songs from the 1960s as a source of easy nostalgia.” I was sort of relieved to read this, because I thought the same thing watching it: Aw, come on, scoring the big group cooking scene to “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg,” a little on the nose, don’t you think? Plus, if they were crazy student revolutionaries in Ann Arbor in 1968, wouldn’t they have been listening to, like, the MC5 and Pharaoh Sanders? I wondered how all this Casey Kasem Top 40 didn’t seem terminally cliched at the time. Perhaps it was, a little bit, but also, maybe deploying those 10-ton nostalgia bombs, less foregrounded in pop culture of the time, was too mighty a force to struggle against for audiences of a certain age and disposition. The songs are loud, too: whenever one of the load-bearing oldies would kick in on the soundtrack, I’d have to turn the TV volume down a few notches.

It’s hard to cut through all of this boomer nostalgia to get to the emotional core of the movie, though I think it’s buried in there somewhere. I’m the same age now (well, a little older) than most of the characters in the movie, and I’ve also had to come to terms with the same questions of drifting away from college friends and youthful ideals. So you’d think there’d be some resonance. There is, but not as much as one might think.

My college experience was very unlike what a person at the University of Michigan in the late 1960s would have experienced. I also didn’t pivot away from those years as acutely, at least in terms of material reward. I was in college through the 2000 presidential election, the 9/11 attacks and the beginning of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, but it wasn’t like the 1960s. Most of my peers were pretty cynical (or just oblivious) to begin with, and any sparkling youthful idealism I remember comes later, more closely correlated with the anti-war movements leading up to the ‘04 election and the election of Obama in ‘08, when the first wave of my friends’ kids were coming in. More importantly, whatever youthful idealism I had, I certainly didn’t trade in for a career in, ahem, the establishment. Almost no one in my cohort makes as much money as their parents made at the same age, whether they wanted to sell out or not. The idea of cashing in youthful radicalism for stock options and business ownership, a point around which many of the characters’ struggles pivot, is practically in the realm of science fiction seen from the second decade of the twenty-first century. It feels so specific to the boomer experience -- the idea that not only is material comfort an ideological betrayal, but it’s there for the taking to just about anyone who wants it -- that it’s hard to go along with the movie’s gentle insistence that this is a type of universal experience.

Change and growth are universal, though, even stripped of their generational context. That opening scene with “I Heard it Through the Grapevine” is great, with poor dead Alex being suited up, and all the group being introduced one-by-one, setting everyone up for the conflicts and conversations to come. Apparently an earlier cut of the film had flashback scenes, which were later excised because test audiences kept laughing at the period clothing. The movie is stronger without the flashbacks, in the same way keeping the dead friend Alex, played by a spectral Kevin Costner, an unseen presence who never appears on screen. (The fact that you probably come into a contemporary viewing of the movie knowing Kevin Costner’s scenes were cut, and knowing what Kevin Costner looked like and what sort of character he’d play, gives it even more extratextual depth.) The characters are drawn reasonably well, which may have more to do with the fact that actors like Glenn Close and Mary Kay Place and William Hurt are so good at what they do. Even when they’re doing things that seem a little off: the final scene between Kline and Place is kind of hard to believe, even though it’s very sweet and Close in particular really makes it seem plausible.

Kasdan based The Big Chill partly on Jean Renoir’s Rules of the Game, which you can still see shown at a festival or on the streaming service of your choice. People can still recognize themselves in the relationship dynamics of that movie, even if they’re not pre-WWII French noblemen and servants spending a weekend on a country estate. In a way, it’s easier to see the resonance when you’re further removed from the immediate cultural context. I wonder how The Big Chill will look to a person 35 years from now, when the familiarity of those songs has dissipated and the cultural baggage of the 1960s doesn’t mean as much. Maybe closer to how Rules of the Game looks to me now, even if The Big Chill isn’t as good a movie.

Come to think of it: isn’t this very Vogue theater project a similar form of gauzy nostalgia, fondly glancing back on the lost world of the youthful past, substituting ‘80s art house movies for Motown hits? When William Hurt tells the rest of the group “a long time ago we knew each other for a short period of time,” that felt like the most real part of the movie, a reminder that people have a way of idealizing their own pasts and, particularly, the relationships they had in those years. That’s a tougher line of inquiry than you get in a lot of the movie, even if it’s a little undercut by the fact that the line is played as more an angry outburst than a trenchant insight.

I might be closer to this than I think.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the Vogue: A preview of coming attractions.

At the Vogue is a (very) occasional movie blog about watching some of the films that showed at The Vogue Theater in Louisville, Kentucky between 1977 and 1998. It’s written by me.

The Vogue was a one-screen neighborhood theater at 3728 Lexington Avenue in the St. Matthews neighborhood of Louisville, a few miles from where I grew up. It’s gone now, but the art deco neon signage is still there. It’s a Paper Source now, from the looks of Google Street View.

The Vogue meant a lot to me, and to my family generally. It was where my parents took me to see Pathfinder when I was 10 years old, a Norwegian movie about a young boy who is separated from his family in the depths of a snowy Northern winter, and is forced to fend off brutal, oafish invaders using only his wits and crudely weaponized contraptions of his own design. If this plot sounds similar to that of another movie from that era, it did to me at the time, too -- I threw a hissy fit about being taken to see this weird, foreign-language impostor instead of Home Alone, like every other normal 10-year-old in 1989. I got over it pretty quickly, though. I haven’t seen Pathfinder in almost thirty years, but it gave me a taste for subtitles that’s stayed with me. (That is, of course, one of the movies I’m going to re-watch here, maybe even with my parents.)

The Vogue was, along with a few libraries, bookshops and record stores in town, a retreat from the suburban landscape I grew up surrounded by -- not just for me, but for my parents, too, who enjoyed (and still enjoy) watching movies together, and occasionally had date nights there. St. Matthews is closer into the core city than where I grew up, though even now, it isn’t particularly cosmopolitan. Most Louisvillians still know it as a place where there are not one but two malls, sitting across from one another on a six-lane highway.

From 1939, when it opened, the Vogue showed regular first-run fare, and somehow survived the postwar incursions of TV and suburbanization that killed off most neighborhood movie houses, in Louisville and everywhere else.

In May 1977, the theater was purchased by a Montreal-born teacher named Marty Sussman, who launched the new repertory format. Sussman mixed in old Hollywood and foreign movies with current independent cinema (and, much to the chagrin of their neighbors, an occasional arty X-rated features like Last Tango in Paris).

For twenty years, the Vogue was about the only place in town to see foreign and art movies, until the Baxter Avenue Filmworks opened in late 1996. (Incidentally, Sussman was one of the new theater’s co-founders, long after his involvement with The Vogue had ended.) “Baxter Avenue,” as everyone knew it, was in a dumpy strip mall on the fringes of the city’s most fashionable neighborhood, but they had six screens with stadium seating, and a huge parking lot. It siphoned off a lot of the Vogue’s business, along with the advent of home video. Wild and Woolly, Louisville’s first specialty video rental shop, opened down the street from Baxter Avenue in 1997. Aside from a great shop like Wild and Woolly, though, even the crappiest Hollywood Video in the crappiest strip mall in the crappiest suburb had at least a handful of foreign and independent movies in stock (and most likely, a handful of movie-obsessed teenage nerds maintaining that stock). Like a lot of movie enthusiasts of my generation, I first saw Kurosawa and Fellini on VHS, not at a theater.

I loved the Vogue, but I didn’t use it as much as I’d like to remember. Though it was only a ten-minute bus ride from my high school, it never occurred to me to regularly head down after classes on a Thursday afternoon and see whatever was playing. This may have had to do with the fact that I was still underage, and most of what showed at the Vogue was rated R -- I always forget how much bullshit you have to put up with as a teenager, at least in regard to what you can and can’t go do, and one thing you really couldn’t easily do was go see R-rated movies. In fact, most of the movies that ended up at The Vogue in the mid-’90s were a little too adult in orientation for a teenager, and not just in terms of their parental ratings -- I’m not sure even the most open-minded 16-year-old could work up much enthusiasm for Bill Paxton in Traveller, or Gena Rowlands in Unhook the Stars, to randomly name two features playing in the afternoons during one particular week of my junior year. So instead, I saved my time, money and effort for the Hollywood Video in the Westport Road Shopping Center.

The Vogue didn’t survive long after Baxter Avenue opened. For most of those final two years, the owners made the bizarre decision to go all in on The Full Monty, which they showed four or five times a day, every day, for most of 1997 and ‘98. I suppose the idea was that regular daily screenings somehow endear the theater to whatever nascent, mindlessly loyal cult the movie was cultivating. There was not, as we now know, a cult around The Full Monty, and even if there had been, four daily screenings is a little bit much for even the most devoted fan.

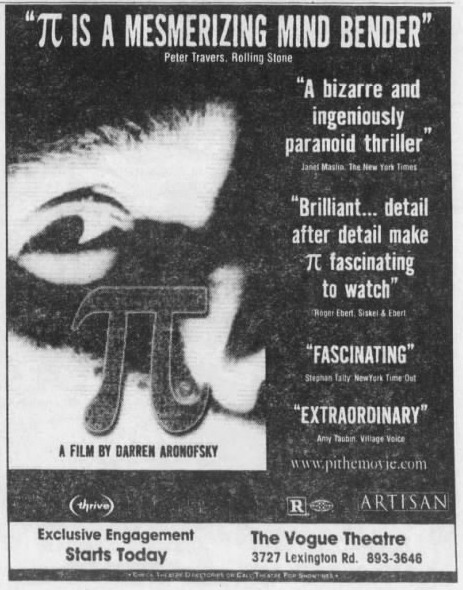

The Vogue closed suddenly in September 1998. One of the last movies they showed was Darren Aronofsky’s Pi. I remember this because me and my buddy Jimbo made plans to see it on afternoon during our freshman year of college, and showed up to find the theater had suddenly and permanently closed a day or two earlier. The queasiness I felt in the pit of stomach that afternoon is one I would feel again and again throughout my adult life, whenever favorite local businesses closed for good. That was the first time I really remember registering it as a new sensation, though: Oh. This place isn’t coming back.

Incidentally, I’ve still never seen Pi.

For the purposes of this blog, I’m going to focus on movies that played there between 1977 to when the theater closed in 1998, with a particular emphasis on the late 1980s and the ‘90s. For the most part, those years mark the first part of my moviegoing life, if we start from the year I saw the 1985 re-releases of E.T. and Return of the Jedi at the Village 8 Cinemas when I was five years old. Most of these movies I wouldn’t have had much interest in seeing before I was 14 or 15 (and probably not for a few years after, in many cases).

All of this has been made possible by one very exciting technological development. Sometime in the past few years, the entire run of the Louisville Courier-Journal was digitized and is now available, fully searchable by date and keyword, to anyone willing or able to pay a small monthly fee to newspapers.com.

This has radically changed my relationship to my own past. It’s become possible to re-read articles I remembered from twenty or even thirty years ago, and investigate my personal history with a thoroughness that would have been much more difficult even five years ago -- finding names of teachers or peers, checking the dates for concerts I went to, re-reading columnists like Jeffrey Lee Puckett, who was (and still is) the C-J’s pop music critic.

For more own viewing purposes, I began slowly assembling a list of movies that played at the Vogue, as a way of creating a counterbalance to the algorithmic recommendations that came my way from Netflix and Hulu. Like most people, I’ve primarily used those services to watch movies since the demise of the video store, and I’ve been increasingly disappointed at how poor the selection is, particularly with older movies. I’ve always been a list-maker, and any tool that helps me make better lists is appreciated. I can trust the programmers of the Vogue’s calendar through the ‘80s and ‘90s as much as anyone or anything.

I’ve been struck by how most of the movies shown at The Vogue have fallen out of fashion. Many of the movies that played in the 1980s and ‘90s are the type that are most easily forgotten: no cults, no major influence on younger filmmakers, harder to find, no real shot at a revival or rediscovery. Most are rentable from Amazon or iTunes, though a few of the most arcane ones have turned up on YouTube, or can be checked out on DVD (or even VHS!) from the library. I’m going to focus on movies that, for whatever reason, aren’t remembered with the same fondness as, say, Blood Simple or Reservoir Dogs, two movies that later played at the Vogue.

Like any blog, it is begun with the very best of intentions, with an eye on updating it faithfully, at least for a while. (A big part of it is that I miss writing shorter, informal pieces for a small audience -- something Tumblr has been great for.) The subject matter is close to inexhaustible. I don’t have an exact number, but that twenty-plus year timeframe represents over 1,000 weeks, during any one of which there were between two and five movies showing daily at the Vogue. So that’s well over 3,000 movies. Even if I manage to write two of these a month -- very unlikely, given my track record -- it’ll be decades before I run out of material.

The Vogue was special. I feel a little bit of guilt about not utilizing it more when I had the chance, but I’m looking forward to visiting it again here.

1 note

·

View note