An educational blog examining the ways in which Asian representation in western media and popular culture has evolved over time. A deep dive into the tropes and stereotypes that have been perpetuated and what that looks like today. Tammy Chou | Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz | 2022

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Post 7: The Shape of Yellow Peril Today: COVID-19 and Anti-Asian Hate Crimes

Between March 2020 and February 2021, 3,795 incidents were submitted to Stop AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islanders) Hate which is likely only a small fraction of actual crimes committed as hate crimes in the community are historically underreported (Low & Davis, 2021). On March 16, 2021, a 21-year-old man walked into three Atlanta-area massage spas and murdered eight people, six of which were women of Asian descent, and law enforcement officials stated the shooter’s self-reported motivation was “sexual addiction” but not racially charged (Low & Davis, 2021). However, after a year of anti-Asian sentiments fueled by a racist and xenophobic president, accompanied by the COVID-19 pandemic which served as an excuse for the unleashing of discriminatory and racially charged hatred, and topped with decades of fetishization of Asian women, many were skeptical of his claims that the attack was not racially motivated. Tajima-Peña, a UCLA Asian American studies professor, says “for us, it’s a no brainer because we know the whole history of these perceptions of Asian women as being expendable. That comes partly from this history [of seeing] women as expendable sex objects -the Asian woman as the foreigner, as the virus” (Low & Davis, 2021).

The surge of anti-Asian racism during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the need to examine the structural roots of racial hierarchy and the persistence of xenophobic violence in Western countries (Chen & Wu, 2021). Chen and Wu (2021) state that “the pandemic has triggered the resurgence of toxic, racialized “Yellow Peril” tropes that defame Asians as “an existential threat to the West, to liberal human rights, to the market economy, to the ‘rules-based’ order, to American primacy” echoing similar sentiments of when the Yellow Peril was first broadly spread in the nineteenth century. The pandemic coincided with the rise of right-wing populism across Western countries and the (re)surgence of white supremacy leading to a national political ideology that formed distinctions between “us” and “them” based on skin color, ultimately contributing to the global rise of anti-Asian racism (Chen & Wu, 2021).

The anti-Asian laws created between 1895- 1950s to define who was a “citizen” and who was a “foreigner” have resulted in the present-day notions of the Perpetual Foreigner and are the embodiment of the “Yellow Peril” threat (Chen & Wu, 2021). Even with the seemingly positive “Model Minority” stereotype which portrays Asians as hard-working, independent, intelligent, and economically prosperous , it minimises and makes the struggles and barriers faced by Asian Americans invisible or non-existent which is very much untrue. Cathy Park Hong, a poet, and essayist argues “Neither Black nor White, Asians are simultaneously stereotyped as model minorities and perpetual foreigners, and thus used as a wedge between Black and white people” (Chen & Wu, 2021).

The way COVID-19 was framed in the media played a major role in the spread of prejudice and xenophobia. By emphasizing the connection between COVID-19 and China and using terms such as “the China virus” or “Kung flu”, the intention to stir up criticism over Chinese cultural practices, the Chinese government, and highlight specific types of Chinese food resulted in the widespread prejudicial response and contributed to the return of “Yellow Peril” tropes in mainstream discourse (Chen & Wu, 2021). Associations of disease, racism, and Asian Americans have recurred time and time again throughout the history of Asians in North America. The linking of COVID-19 with China "invokes a well worn narrative of Chinese people as "diseased"", which was a link that was also present during the SARS outbreak in 2003 (Adetunji, 2020). The language that has persistently been used to cast Asian and particularly, Chinese comunities, as foreign and dangerous has resulted in the dehumanization of Asians who are "stripped of their humanity before their marginalization can be justified" (Adetunji, 2020).

To sum it up, “the escalation of socio-political conflicts, worsened by the ongoing pandemic and sharpened by Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric, is undeniably responsible for the loss of lives caused by anti-Asian hate crimes” (Chen & Wu, 2021). We can see that everything discussed from the first post and the origin of the Yellow Peril, the various ways in which Asians and Asian Americans have been represented in western media have resulted in the state of affairs for Asians living in Western societies around the world today. The recent increase in representation and authentic portrayals of Asian lives and stories is just one small step in fighting the decades if not centuries of inaccurate and harmful portrayals of Asians and those deemed as the “Other” to mostly western and white communities.

Chen and Wu have put together a set of questions that interweave gender, racial, national, and class differences to target and initiate transcultural conversations. These questions include asking how to counter systemic racism in public institutions. How to debunk the “model minority” myth? How to build a united front between Asian communities and other ethnic groups suffering from systemic racism? How can Asian communities contribute to policy discussions on reconciliation and future directions of Canadian multiculturalism? And how to overcome or tackle questions of redistribution and wealth (Chen & Wu, 2021). Showing that the current surge of anti-Asian racism is a “multilayered, translocal phenomenon that can only be dealt with by transcultural solidarity and joint efforts through both top-down and bottom-up approaches (Chen & Wu, 2021).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post 6: Paradigm Shift of Asian American Representation in Media

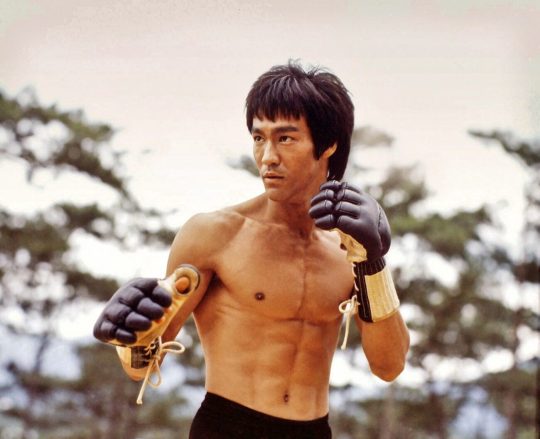

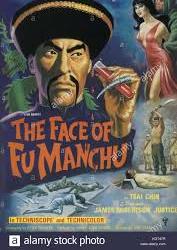

After decades of misrepresentation, the gendered stereotyping of Asian men and women as discussed previously, from Fu Manchu and Dragon Lady/Lotus Blossom tropes, the usage of yellowface, cultural appropriation, and the limiting of Asian actors to a few racially stereotypical roles, at last the racial barriers built by Hollywood were kicked down upon the arrival of Bruce Lee.

While Lee managed to gain some popularity with his role in the tv series The Green Hornet (1966), he was overlooked for lead roles in favor of white actors (Low, 2021). He then decided to leave the U.S. for Hong Kong to advance his career as an actor where he was catapulted to fame after the release of The Big Boss (1971) which was a huge box office success (Blake, 2018). Other films such as First of Fury (1971) and The Chinese Connection (1972) brought Lee into further spotlight which resulted in Hollywood becoming interested in him once again. After Lee revolutionized Hong Kong martial arts cinema, he went on to break through U.S. mainstream media and reconstructed the way Asians were depicted on screen by starting the “kung-fu craze” in the 70s (Desser, 2002).

The unprecedented success of Lee marked a paradigm shift in Hollywood where Asian men, in particular, had previously been pigeonholed into roles as submissive servants, unskilled laborers, reincarnations of Fu Manchu, geeky sidekicks, unattractive, and comedy relief (Low, 2021). This paradigm shift became both a curse and a blessing as his popularity in the 1980s led to the entrenchment of the “All Asians Know Martial Arts” trope (Low, 2021). New martial arts actors that followed such as Jackie Chan and Jet Li were both referred to as “the next Bruce Lee” and martial arts films from this decade went on to inspire and influence action films and martial artists for generations after, even to this day. Bruce Lee is a prime example of the ways and possibilities that powerful stereotypes that have been around for decades can be challenged and broken and consequently change representations of Asian and Asian Americans for generations after.

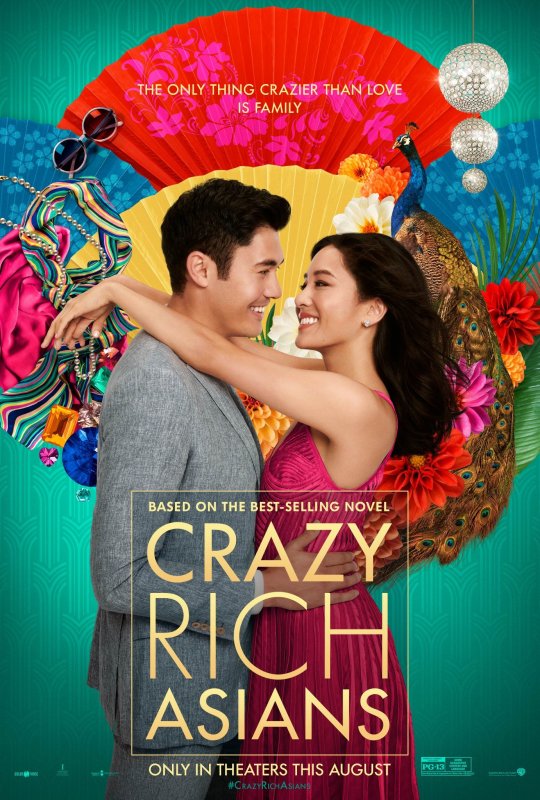

Following Bruce Lee, the year 2000 was a triumphant year for Asian cinema with Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love premiering at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival and Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon also making its premiere (Low, 2021). Both films were game-changers for Asian films in international theatres but it wasn’t until the release of Crazy Rich Asians (2018) which marked a momentous step in Asian representation being the first film with an all-Asian cast since The Joy Luck Club in 1993 and breaking a record in its premiere as the highest-grossing romantic comedy in a decade (Calub, 2021). The Farewell (2019) also received praise for its authentic depiction of Asian families.

The 2020s marks the “golden age” of Asian representation in cinema, with films such as Minari (2020) winning best supporting actress Oscar for Yuh-Jung Youn (the second ever actress of Asian descent to win in that category) and showcasing an American story with characters not typically seen as American, Parasite (2019) going on to win four Oscar awards, Director Chloé Zhao winning best director for Nomadland (2020) and being chosen to direct the next epic Marvel film Eternals (2021), Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings (2021) being the first-ever Asian-led superhero film to make it to theatres, and Squid Game (2021) being the first Korean tv show making history as the most-watched show on Netflix and topping streaming company’s drama charts in all 83 countries (Calub, 2021). All of these allowed Asians and Asian Americans to catch a glimpse of themselves on screen in a way that hasn’t really been shown before however, these films are mostly representing East Asians and not South or Southeast Asians who are still severely underrepresented in mainstream media.

Despite these major breakthroughs in Asian cinema, a study called “I am not a Fetish or Model Minority” reviewed the top 10 grossing movies each year from 2010 to 2019, and noted that among those films, only 4.5 percent of the main cast were Asian and Pacific Islander roles which show that there is still far ways to go in Asian representation and these are just the first steps. Nancy Wang Yuen, a sociologist, told NBC “That just speaks to the lack of authority that Asians have to be able to tell their own stories in Hollywood and the kind of trope of using Asians as objects” (Calub, 2021).

To tackle issues of underrepresentation and increase diversity, Netflix released a study to analyze the makeup of Netflix’s on-screen talent including creators, producers, writers, and directors to see where it can improve on closing diversity gaps (Boorstin, 2021). The streaming platform will work on asking questions like “Whose voice is missing? Is this portrayal authentic? Who is excluded?” as it commits to an “inclusion lens” to its work (Boorstin, 2021). The company has created a fund called Creative Equity where it plans on investing $100 million over the next five years “in organizations that help underrepresented communities train and find jobs in TV and film” as well as releasing an update to this study every two years until 2026 (Boorstin, 2021). The co-CEO Ted Sarandos says “doing better means establishing even more opportunities for people from underrepresented communities to have their voices heard, and purposefully closing capacity and skill gaps with training programs where they are needed” which gives traditionally underrepresented and often misrepresented communities hope for finally being able to see a glimpse of themselves and their communities on-screen (Boorstin, 2021).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post 5: Hollywood and the Gendered Stereotyping of Asian American Men (Part 2)

Asian men on the other hand, have a history of being emasculated by Western media, depicted as sexually inadequate and unattractive figures who are undesirable or seen as ruthless sexual threats to white women (Johnson, 2004). The image of emasculation began in the early 1900s due to the physical appearance of Chinese labourers as they sported long queues and wore traditional Chinese gowns that looked like women’s wear in the west (Yang, 2011). As mentioned previously with the rise of the Yellow Peril, the economic competition brought by the large influx of Chinese workers was seen as a threat to the white workforce resulting in negative depictions of Asian men to bar more Asians from entering the country and to attempt to put the rest of society against the ones who had already arrived.

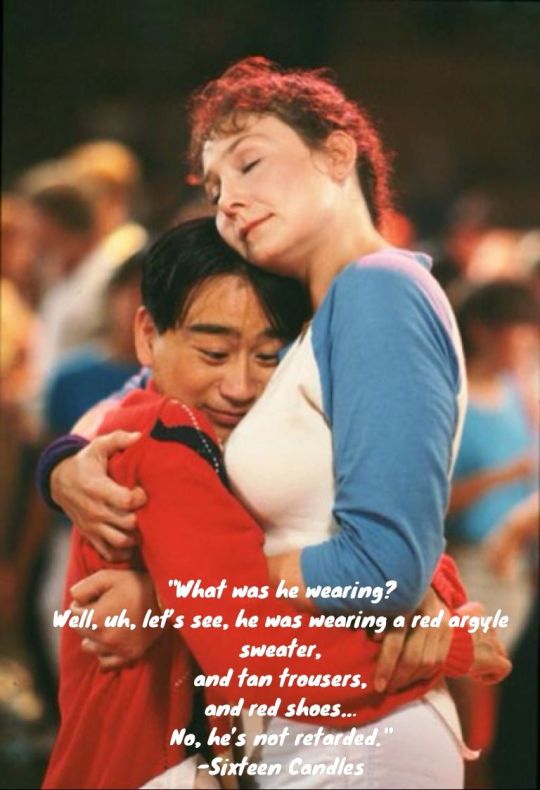

In U.S. mainstream media, much like the stereotyped representations of Asian women, Asian men have also been constructed into two opposing types of characters. The first type was constructed during the Yellow Peril with Asian men depicted as “undesirable, barbaric, uncivilized, diseased, and predatory of white women” which represents the perceived danger of Asian men to white society, and later on, also constructed to be “emasculated, asexual and nerdy as delivery boys or computer geeks without any physical attractiveness” (Yang, 2011). Oftentimes, Asian males are used in Hollywood films as comic relief by making them the butt of the jokes and someone to be laughed at. One primary example of this stereotype of Asian male characters can be seen in the film Sixteen Candles (1984) with the character Long Duk Dong where his entire Asian identity is caricatured and used for comedy. He speaks English with a heavy accent and is depicted as the feminine one in his relationship with his much taller and stronger girlfriend “Lumberjack”. The gender reversal in this relationship is intended to be comedic while perpetuating the stereotype of Asian men as feminine, unattractive and asexual (Yang, 2011).

Other films with similar stereotypes of Asian men include The Goonies (1985), and Mr. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) where Mr. Yunioshi is a Japanese photographer played by a white actor in yellowface (Low & Davis, 2021). In Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo (1999), Asian and Asian American males are once again depicted as sexually and racially inferior while also serving as “humor” and comedy to non-Asian and non-Asian American audiences (Yang, 2011). Throughout the 20th century, Asian and Asian American men have been constructed in positions of powerlessness and inferiority to all other men including Black and Hispanic men. The contrasting sexualization of female Asian bodies and emasculation of Asian men “serve as a foil to the masculinity of white men” (Johnson, 2004).

The effect of these harmful portrayals is still evident today with Asian males struggling to fight against the stereotype that they are asexual and undesirable. In a study done on online dating in 2020, "Asian men in North America are much more likely than men from other racial groups to be single" (Yue, 2020). Yue goes on to say that "seemingly personal preferences and choices in modern romance are profoundly shaped by larger social forces, such as unflattering stereotypical media depictions of Asians, a history of unequal status relations between western and Asian countries, and the construction of masculinity and femininity in society. Regular exclusion of a particular racial group from having romantic relationships is known as sexual racism" (Yue, 2020). This shows the extent to which these negative portrayals of Asian and Asian American men have very real consequences in the day to day life whether through subconscious biases from having been exposed to these notions through mainstream media which then turn into an active choice to exclude Asian men.

0 notes

Text

Post 4: Hollywood and the Gendered Stereotyping of Asian American Women (Part 1)

While Asians and Asian cultures have been underrepresented and stereotyped in Western media, Hollywood has been a major factor in promoting negative stereotypes and pigeonholing Asians into specific roles which are typically gendered. To better understand how race, gender, and sexuality play into the representations of Asians and Asian Americans, we will look at this section through an intersectional approach.

One of the primary reasons why Asian and Asian American men are represented differently from Asian and Asian American women has to do with the history of colonialism - “its logic has significant influence in the ways that the Western mainstream media represents people of color” (Yang, 2011). The popular depictions of Asian women as sexually submissive and alluring and Asian men as asexual and degenerate or villainous suggest that Asian men are inferior to white men as they are deemed undesirable and thus making it “free” for white men to have a romantic relationship with Asian women who are sexual and desirable. Similar to the discourse that Native American women needed to be “saved” from the barbaric Native American men, Asian and Asian American women also need to be freed from deceptive and uncivilized Asian men (Yang, 2011). Gender, race, and sexuality are important factors in determining the power positions of different races and genders - where one is portrayed in positions of power and dominance, the other is situated in positions of powerlessness, submissiveness, or subservience.

Asian women are sexualized and portrayed in two contrasting images: the Dragon Lady who is deceitful, mysterious, and a sexual criminal used as a female embodiment of Western fear of Asians and Asian Americans or the second image being the “China Doll” who is a docile “sexual-romantic object”, submissive, obedient, and “utterly feminine, [and] delicate”, also known as Geisha girls, Lotus Blossom, or Madame Butterfly (Tajima, 2003). The Dragon Lady is “untrustworthy, deceitful, conniving, and plotting, and she may use sex or sexuality to get what she wants, including the objects of her sexual desire” whereas the China Doll is in a position of powerlessness and needs to be rescued (Yang, 2011). Both the Dragon Lady and China Doll are exoticized and hyper-sexualized beings used in mainstream Hollywood films, pornography, magazines, leading to the ‘widespread perception that Asian women are inherently, exotically sexual” (Yamamoto, 2000). The objectification and commodification of these women’s bodies do not provide visibility for them as individuals but rather show them as objects of desire -particularly for white men, but ones that are disposable.

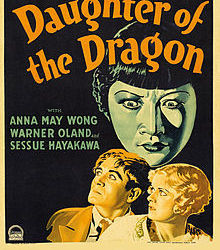

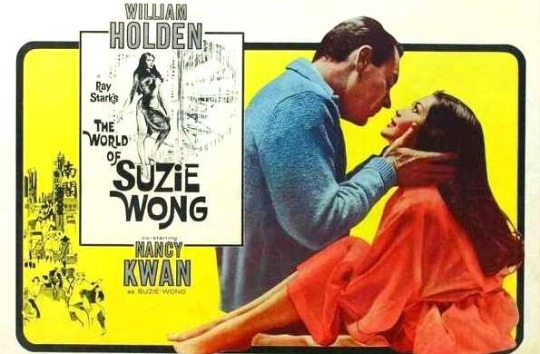

Films such as The World of Suzie Wong (1960), Sayonara (1957), and Slaying the Dragon (1988) depict images of the China Doll or Lotus Blossom with Asian and Asian American women as “submissive, obsequious, and self- sacrificial for the white U.S. military personnel” (Yang, 2011). On the other hand, Anna May Wong, one of the first Chinese American Hollywood stars, was often typecast as the Dragon Lady. She plays the daughter of Fu Manchu in the film Daughter of the Dragon (1931), and other similar Dragon Lady roles in films such as Shanghai Express (1932) and The Thief of Baghdad (1924) amongst others (Low, 2021). Although Wong was one of the first Asian American actresses paving the way for Asian representation on screen, she was ultimately unable to break through the Dragon Lady stereotype with Time magazine describing her as “the screen’s foremost Oriental villainess” and Wong herself saying “I was tired of the parts I had to play. Why is it that on the screen the Chinese are nearly always the villain of the piece, and so cruel a villain -murderous, treacherous, a snake in the grass. We are not like that” (quoted from Thi Thanh Nga, 1995 in Johnson, 2004).

Lucy Liu, another prominent Asian American actress also played the Dragon Lady in various forms in films and television series such as Payback (1991), Ally McBeal (1997), and Kill Bill (2003) (Low, 2021). Other contemporary Hollywood films with the same construction of the mystical, unusual and sexually dangerous Asian woman with a desire for revenge include Year of the Dragon (1985), Come to See the Paradise (1990), and Thousand Pieces of Gold (1991). These films also have one major theme in common - interracial sexual relationship between a white man and an Asian female showing the authority and power the white male has over both Asian and Asian American men and women (Yang, 2011).

The China Doll and Dragon Lady stereotypes have been firmly rooted in U.S. mainstream media and the characteristics of Asian women as submissive, obedient, and sexually alluring make them easy sexual targets and result in the fetishization of Asian female bodies. The common interracial depictions of U.S. military personnel and Asian women also represent the power relation between Asian nations and the U.S. Decades of this type of representation have had very harmful effects on Asian and Asian American girls and women who grow up feeling disempowered and “unable to see themselves as leaders or as anything more than that especially when these images have an impact on the way they’re treated in society” (Calub, 2021).

0 notes

Text

Post 3: Orientalism in Disney

Disney has played a major role in terms of media and entertainment for children and families around the world and many people look back at Disney films nostalgically. However, it’s hard to deny that Disney is known for its range of diverse characters. Although they have attempted to step it up over recent years to be more inclusive and feature more characters of color, there is still much work to be done especially when looking back at the many films showcasing racial caricatures and perpetuating negative stereotypes.

Growing up as a young, Asian girl in Canada, I didn’t realize until I was much older, that I had always been subconsciously looking for characters that looked like myself on screen, and perhaps that’s why I always held a soft spot for Mulan in my heart. That being said, coming back to this movie now, the glaringly Orientalist representations scattered throughout this movie make it hard to really enjoy. The few other Disney movies featuring non-white characters such as Aladdin and Pocahontas also display Disney’s racist understanding and viewing of Asian and non-White cultures. The Western perspective “is a view of the world through a colonialist lens, in turn producing perceptions of those from the East as a singular group”, merging Asia and the East into one. As Edward Said puts it “orientalism refers to the manner in which the Westerners interpret Asians and Asian cultures with their own knowledge, experience and encounters with the Orient and the culture” (Said, 1978). It is a concept created by Europeans to reflect their understanding but also as a means to justify their actions and beliefs while promoting a certain narrative about the Western “us” and Oriental “them”, usually painting those from Eastern cultures in a negative light.

In Mulan, all of the characters are depicted with Orientalist markers such as slant eyes, round moon faces, long straight hair, and goatees for males (Ma, 2000). Although Mulan is set in China, she is seen wearing a Japanese kimono and sporting white powdered makeup generally used by Japanese geishas. This shows the mixing of various Eastern cultures depicted as one, which falls in line with the Western perspective that looks at the world through a colonialist view and groups those from the “East” as a singular group.

Although Disney tries to incorporate what seem like authentic details of China and Chinese cultures such as the use of chopsticks and calligraphy ink brush, the way they are used shows a carelessness in really understanding these cultural customs. As Ma states “no Chinese would be so ill-mannered as to thrust the chopsticks upright in the rice bowl. No rice bowls, for that matter, would pile up like a mound. She writes with a brush, but her calligraphy winds up on her wrist” (Ma, 2000). Furthermore, one of the main themes of the movie is centered around the idea of Mulan having to bring “honor” to her family through self-sacrifice, which is a very clichéd notion often presented in western movies, that Asian people live in pursuit of one thing: honor.

Aladdin is another Disney film that demonstrates “classic Orientalist understandings of Asia, through the othering and exoticizing of the characters and the setting of the movie” (Ramirez, 2020). Aladdin is set in a fictional place - Agrabah, however, it takes direct inspiration from Baghdad, the palace is modeled after the Taj Mahal in India, the desert in which Aladdin finds the treasures is inspired by the Arabian desert, once again merging a number of South Asian countries together to create this fictional location (Ramirez, 2020).

The characters in Aladdin also represent problematic Orientalist tropes -for example, Jafar, the evil villain of the story who is also a sorcerer and obsessed only with gaining power and wealth. Jafar exemplifies the character trope often used by Western media to depict Middle Eastern people as a singular one, who share similar characteristics of being wicked and spiteful. His physical appearance with the long jaw, a curled thin beard, and large nose is also a problematic depiction of Asian and Middle Eastern features and shares similarities with Fu Manchu, the main image of “Yellow Peril”.

Alongside the villainization of Middle Eastern characters, Aladdin also sexualizes and exoticizes women and particularly Middle Eastern women. Princess Jasmine is far more sexualized than any other Disney princess and wears the most revealing and sheer garments which she uses to seduce her way out of captivity. Women living in the fictional Agrabah are also dressed in sheer garments with exposed midriffs, presenting a hypersexualized image of Middle Eastern women.

These depictions of Asia and the East are harmful as they perpetuate stereotypes and prejudices about Asians and Middle Eastern people while also pushing a unilateral and generalized identity. Furthermore, these are films catered to children, and exposing them to such stereotypes can have a negative influence on the way they perceive people of different cultures or the way they see themselves.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

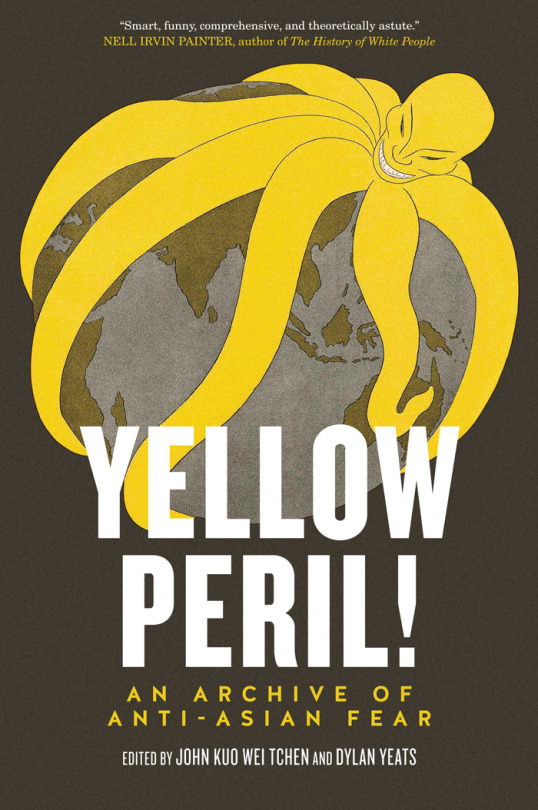

Post 2: The Origins of Yellow Peril and Subsequent Asian Stereotypes

Although fear of the “Yellow Peril” began to spread around the late nineteenth century, the concept can be traced back to the fifth century (BCE) looking at the ways the Greeks thought about the Persians (Okihiro, 1994). Okihiro also suggests that the concept may have originated in the medieval era, particularly from the fear of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian invasion of European land (Okihiro, 1994). He states in his book “Yellow Peril combines the racist terror of alien cultures, sexual anxieties, and the belief that the West will be overpowered and enveloped by the irresistible, dark, occult forces of the East” which show that the original Yellow Peril stemmed from hatred and fear of the unknown “Other” and their strange cultures (Okihiro, 1994).

For Asian Americans, the concept of the “Yellow Peril” is the most long-standing stereotype and originated during the wave of Chinese immigration to the United States as laborers (Wu, 2002). In the mid-twentieth century, this term became linked with a large number of Japanese immigrants. Regardless of which Asian country it refers to, the Yellow Peril discourse “emphasizes the powerful, threatening, and extensiveness of Asians and Asian Americans, while depicting whites as vulnerable, threatened, and in danger” (Yang, 2011).

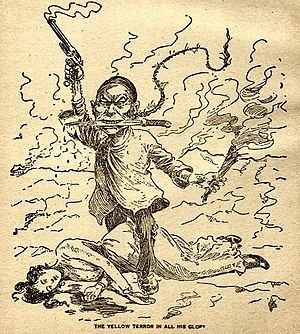

These early depictions of the East go through various periods of different representations: firstly as racial and social pollutants from the mid-nineteenth century, then from the 1860s to 1870s as drug users and sexual deviants, then from 1870s to 1880s as coolies, and from the 1880s as a great threat to white people and particularly white women (Yang, 2011). At the height of the Yellow Peril discourse, it was being broadcasted that “nonwhite people are by nature physically and intellectually inferior, morally suspect, heathen, licentious, disease-ridden, feral, violent, uncivilized, infantile, and in need of the guidance of white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants” (Marchetti, 1993). These racial discriminations led to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 and laid the foundation for political scapegoating (Tchen & Years, 2014). In 1905, the Asian Exclusion League (AEL) was formed to try and drive out all Asians and Asian Americans as well as prohibit Asians from immigrating to the United States (Yang, 2011).

The Yellow Peril discourse was not merely a political discussion but also showed up in journalism and media as well. Newspapers depicted Asians as an inferior race with William F. Wu defining the Yellow Peril as: “the threat to the U.S. that some white American authors believed was posed by the people of East Asia. As a literary theme, the fear of this threat focused on specific issues, including possible military invasion from Asia, perceived competition to the white labor force from Asian workers, the alleged moral degeneracy of Asian people, and the potential genetic mixing of Anglo-Saxons with Asians, who were considered a biologically inferior race” (Wu, 2002). Much of these negative perceptions stemmed from the fear and hostility brought upon by the economic competition that came with the increase of Asian workers. Even though the Yellow Peril was the first of the stereotypes to be formed against Asians and Asian Americans, it has persisted through the twentieth century and is still very much alive today as we will discuss later on.

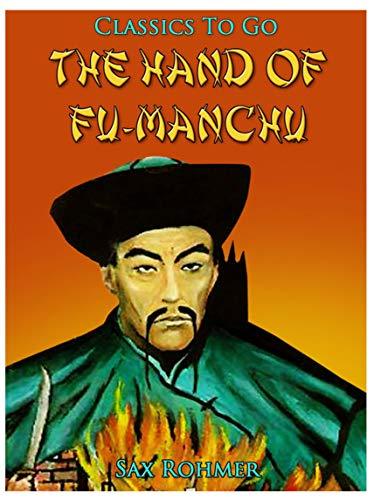

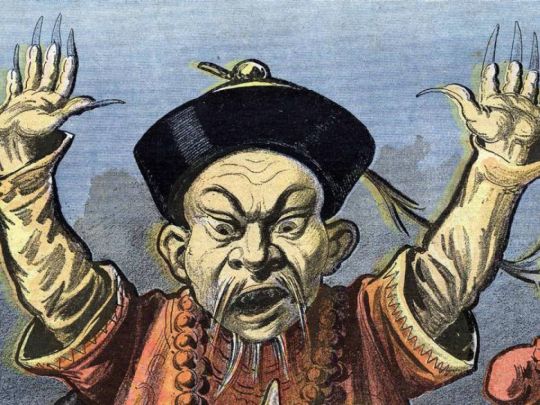

All of these early fears and depictions of Asians and particularly a paranoia about an “Asian horde that will overwhelm the white people of the world”, resulted in the creation of the comic character, Fu Manchu, created by Sax Rohmer who admitted he knew nothing about the Chinese, but which became the personification of Yellow Peril and “represented the tension between the morally pure and superior West and the “mysterious, seductively evil East” (Wu, 2002). As the representation of Yellow Peril, Fu Manchu “perpetuates the myth that the Chinese, and by extension, Asians, are trying to take over the Western world” and became the outlet for American fear of the Orient (Chan, 2001). The recurrence of the orientalized “Other” used to enhance the “visibility/racial invisibility” of whites is done by promoting the “permanent status of Asians as the perpetually foreign, invisible other” (Johnson, 2004).

The “Perpetual Foreigner” is a stereotype of Asian Americans depicting that all Asians and Asian Americans come from a faraway place with different languages, cultures, and ideologies and cannot understand or be a part of mainstream American culture (Yang, 2011). This leads to the misconception that Asian Americans -even those who are born, raised, and educated and have been for perhaps multiple generations, are still seen as foreigners who cannot speak English fluently or do not understand American culture. This perception makes it difficult for Asians to take part in society because they are deemed unassimilable to the mainstream white society and deemed foreign and invisible. The main ideas that underlie this stereotype are that first, the United States belongs to the whites; and secondly, there is not much difference between race and culture, “the outside, reflected by the race, is thought to represent the inside, one’s culture, custom or world view” meaning that no matter how long Asians and Asian Americans live in the United States, they will still be seen as the “foreigner” and “outside” of mainstream society (Yang, 2011).

The “Model Minority” stereotype originated in the 1960s during the civil rights movement and has a seemingly positive connotation that includes traits such as “hardworking, politically inactive, intelligent, productive, and inoffensive” however, it was used to pit Asian minorities against other racial minorities such as the Black and Latino communities who were labeled “immoral, unethical, lazy, and violent” (Yang, 2011). The Model Minority myth is also dangerous for Asians and Asian Americans as it erases the cultural, political, and social barriers that Asians face and struggle with.

https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51A-9VBMd-L.jpg

1 note

·

View note

Text

Post 1: Introduction - Representation Matters

Record times spent consuming media of all forms, notably film and television, have been reported over the last few years, particularly due to the pandemic that swept across the globe, forcing millions to stay at home or quarantine and resulting in a considerable uptick in media consumption. With these record viewer numbers, the accurate representation of diverse communities becomes increasingly important as people of all backgrounds are consumers of media and are impacted by what they see to varying degrees.

The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic had another effect as its apparent origin from Wuhan, China, coupled with deteriorating relations between the United States and China, along with an American president who broadcasted and encouraged white supremacy and anti-China rhetoric resulted in a surge of Anti-Asian violence in the United States and spread like an additional virus around the globe. The blatantly racist and xenophobic statements made by the American president and echoed in mainstream media played into “Yellow Peril” sentiments stemming from the 1800s which have been a recurring theme throughout Asian representation in Western media.

Stuart Hall states "that concepts and memories of experiences that are special to individuals help dictate how dominant ideas of the world come into being" and most media producers and directors have their own subjective knowledge and experiences about Asians and Asian Americans (Yang, 2011). As a result, representations, such as Yellow Peril or other stereotypes, can come into being and spread in broad society (Yang, 2011).

Although a lack of representation is harmful in itself, misrepresentation and perpetuation of harmful stereotypes have very damaging consequences. The flawed portrayals of already underrepresented groups can be internalized by individuals of the group being stereotyped as well as other members of society and go on to influence public opinion of these communities. It is particularly dangerous when these biases are institutionalized, leading to issues of discrimination, hate crimes, police brutality, mass incarceration of disadvantaged communities and more (Huang, 2021).

This blog will be focusing on the evolution of Asian representation (mostly East Asian representation) throughout the last century in Western media and examine the ways in which the stereotypes depicted on-screen bleed into real life and affect Asians off-screen. Decades of harmful portrayals along with the invisibility of Asians and Asian voices have led to the current state of affairs for Asian Americans but also for Asians living in other Western societies, particularly explaining the recent surge of anti-Asian hate crime that has circulated around the globe simultaneously with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some of the main themes and tropes we will explore are the ways in which Edward Said’s ‘Orientalism’ appears as a pervasive element in the representation of Asians in media, how “Yellow Peril” came to be, and the way it has transformed throughout the years depending on the changing relations between primarily China and the West, how the “Perpetual Foreigner” and “Model Minority” tropes came to be and the consequences of these portrayals, as well as the gendered stereotypes of Asians which have very damaging consequences to this day. This blog will also look at the recent changes in Asian cinema and the form Yellow Peril has taken today in relation to the pandemic as well as how major streaming services such as Netflix are combatting misrepresentation and lack of representation for minorities and marginalised communities.

Representation matters. What we see on screen -in films, television, digital media, etc. has an impact on the way we see others, as well as ourselves. It influences the way we look at our relationships with people of different backgrounds and allows people to feel seen and included. It also breaks down barriers and opens up people’s perspectives on different cultures and ways of living. It allows for authentic stories to be told when they have been excluded or made invisible in the past. Although this blog is only looking at Asian representation, all representation matters, and the fight toward more inclusivity and diversity on screen has only just begun.

0 notes