Text

What is a Novel? Heteroglossia and David Yoon’s Frankly in Love

In reading, we often focus so much on determining what we are reading about and forget to think about how we are reading about it. In thinking about how to define and classify the genre of young adult fiction, I began to think about its parent genre–the novel. The novel is most likely the predominant mode of young adult fiction because of when the genre emerged; according to Michael Cart, in 1942 (Cart 11). Evidently, the popularity of epic and poetry had long been replaced by the novel when young adult fiction’s genesis occurred. The novel has remained the predominant mode of young adult fiction to this day; from the “golden age” of the genre–S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders, Walter Dean Myers’ Fast Sam, Cool Clyde, and Stuff, Judy Blume’s Forever, Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War, Sylvia Engdahl’s Enchantress from the Stars, and Richard Sleator’s House of Stars, to recent YA phenomena like the Twilight series, The Hunger Games, the works of John Green, Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give, and the novel I will analyze today, David Yoon’s Frankly in Love. Although the styles of each work are evidently distinct, from first person to third person, realism to dystopian, and about widely different aspects of adolescence, each work is undeniably a novel. So, in order to determine what the novel serves to represent adolescent experience, one first has to ask what is a novel? Keep reading to find out.

Synopsis of Critical Theory

Although I doubt Mikhail Bakhtin would have intended his notion of heteroglossia (literally different tongues/languages) to be related to young adult fiction, I do not think his argument is inconsistent with the genre. In “Discourse in the Novel” Mikhail Bakhtin defines the novel as ��as a diversity of social speech types, sometimes even diversity of languages and a diversity of individual voices, artistically organized” (Bakhtin 32). Then, Bakhtin insists that “Literary language” “is itself stratified and heteroglot in its aspect as an expressive system, that is, in the forms that carry its meanings” (Bakhtin 33). Such stratification, Bakhtin outlines, is “generic,” “professional,” “social,” “historical,” and “socio-ideological” (Bakhtin 33-34).

Thus, the language of the novel reflects the various stratifications of language in real life:

all languages of heteroglossia, whatever the principle underlying them and making each unique, are specific points of view on the world, forms for conceptualizing the world in words, specific world views, each characterized by its own objects, meanings and values. As such they may be juxtaposed to one another, mutually supplement one another, contradict one another and be interrelated dialogically. As such they encounter one another and co-exist in the consciousness of real people – first and foremost, in the creative consciousness of people who write novels. (Bakhtin 34)

Bakhtin also argues that language is at the same time individual and related to that beyond oneself: “As a living, socio-ideological concrete thing, as heteroglot opinion, language, for the individual consciousness, lies in the borderline between oneself and the other” (Bakhtin 35).

Ultimately, through his definition of the novel as heteroglot, Bakhtin concludes that interpretation is infinite: “The semantic structure of internally persuasive discourse is not finite, it is open; in each of the new contexts that dialogize it, this discourse is able to reveal ever newer ways to mean” (Bakhtin 44). Due to the fact that the reader’s relationship to language is heteroglot and stratified in ever new individual ways, people will inherently read the novel in different ways at different times. In thinking about how this relates to the genre of young adult fiction and my own experience of reading works from the “golden age” of YA, I determine (and I think Bakhtin would agree) that it is still valuable to read such works in 2020. Although I may not read Blume’s Forever as someone would have in its year of publication, that does not make my interpretation any less valuable, In fact, Bakhtin’s idea democratizes interpretation, in that no interpretation can be privileged over another, because they are all as individualistic regardless of who the reader is and when they read the work.

Application

Although I could argue for the heteroglossic nature of each work of “golden age” YA I outlined above, I think recent trends in the genre, as exemplified in David Yoon’s 2019 Frankly in Love, allow for a clear connection between the novel and heteroglossia. As YA fiction has become increasingly more diverse so too has its language. For instance, in Frankly in Love Yoon stratifies language between that of English (Californian), Korean, Spanish, text, email, student, son, friend, and boyfriend (Yoon 39, 43, 62, 65, 67, 70, 109, 131, 133, 259, 293-294, 376, 379, 401). This list is not extensive, and I encourage you to see what other types of languages (‘generic,’ ‘professional,’ ‘social,’ ‘historical,’ and ‘socio-ideological’) your students can identify in reading the text.

The novel is self-aware of the various languages it uses to represent the narrative. In fact, the narrator, Frank, explicitly calls out such a practice: “In Language class Ms. Chit would call this code switching. It’s like switching accents, but at a more micro level. The idea is that you don’t speak the same way with your friends (California English Casual) that you do with a teacher (California English Formal), or a girl (California English Sing-song), or your immigrant parents (California English Exacerbated). You may change how you talk to best adapt to whoever you’re talking to” (Yoon 39). Although Frank refers to “code switching” here rather than the stratification of language that is heteroglossia, the variety of languages present in the novel is still the central idea. Thus, the definition of code switching that Frank provides only further highlights the multiple languages he uses, and that consequently Yoon uses in the novel.

Frankly in Love not only exemplifies heteroglossia, but also reflects and encourages Bakhtin’s notion that there are ‘ever newer ways to mean.’ This perhaps is best reflected in the title of the novel, which serves as a pun for the main character’s name: Frank Li. Thus, the title can be interpreted both figuratively and literally. The novel is literally about the protagonist, Frank Li, in love, and is figuratively an honest and “frank” account of being in love. Therefore, the title alone encourages readers to interpret words in multifaceted ways and nods to the multiple meanings of language depending upon the reader and context.

To return to my initial question, then, the novel serves to represent the various languages of adolescents. Consequently, adolescents, as readers, provide a unique perspective and relationship to language that perpetuates words’ quality to possess ‘ever newer ways to mean.’ Ultimately, Young Adult fiction, as a genre comprised of novels, intersects with a variety of languages, but predominantly is defined and interpreted by the language of adolescents.

Discussion Questions

How does Frankly in Love reflect Bakhtin’s notion of heteroglossia?

How does Yoon stratify language in the novel? What languages does the novel rely upon to tell Frank’s story?

How does Frankly in Love promote the idea that language is both individual and representative of the “other”?

Works Cited

Bakhtin, Mikhail. “Discourse in the Novel.” Literary Theory an Anthology, edited by Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan, Blackwell Publishers, 1998, p. 32-44.

Cart, Michael. “From Sue Barton to the Sixties.” Young Adult Literature from Romance to Realism, Chicago, Neal-Schuman, 2016.

Yoon, David. Frankly in Love. New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2019.

0 notes

Text

Beyond Values: Semiotics, Signifying and Fast Sam, Cool Clyde, and Stuff by Walter Dean Myers

I know that probably the last thing you want to read about right now is semiotics. Maybe you do not even know what that word means (study of sign systems), and the esoteric title of this post alone repels you to continue reading. Maybe you’re content with reading Myers’ work through his statement of purpose: “Books transmit values. They explore our common humanity. What is the message when some children are not represented in those books? Where are the future white personnel managers going to get their ideas of people of color? Where are the future white loan officers and future white politicians going to get their knowledge of people of color? Where are black children going to get a sense of who they are and what they can be?” (“Where Are the People of Color in Children’s Books?”). Although I see merit in viewing works as such value-producing machines, I think that ignoring the function and significance of language in literary entities is irresponsible. Myers decided to ‘transmit values’ through the written word: not drawing, painting, or music. His chosen mode of communication is not insignificant, for such a mode inherently draws attention to the ability of words to signify meaning. And of course, that’s what The Good People are all about: communication. Clyde states, “‘And when we have problems, we’ll talk about them?’ Clyde asked. Everybody agreed” (Myers 77).

In fact, in Fast Sam, Cool Clyde, and Stuff, Myers draws attention to the word from the very first page: “This is a story about some people I used to hang out with. It’s funny calling them people. I mean they’re people and everything, but a little while ago I would have called them kids” (Myers, 7). From the onset, Stuff grapples with the right word, the best word to use to signify who his friends were. As I will outline in this post, throughout the work, Myers continues to implicitly emphasize the function of language. Before I begin to do so, however, I think it is notable to highlight an explicit mention of semiotics, or signification, to persuade you to understand that semiotics are significant to Myers’ text: “Gloria was one of those girls that was always signifying–saying something to get something started or make someone mad” (Myers 19). Myers’ direct use of this word serves two purposes. First, in the context of the text and Gloria, it relates to the African American tradition in which “Signifying is verbal play - serious play that serves as instruction, entertainment, mental exercise, preparation for interacting with friend and foe in the social arena. In black vernacular, Signifying is a sign that words cannot be trusted, that even the most literal utterance allows room for interpretation, that language is both carnival and minefield.” (Wideman). But, I would also argue that Myers’ use of such a word reflects Gloria, in that it plays with double-meanings. Of course, Gloria is ‘signifying’ within the African American tradition, but Myers is signifying, in this very work, within a semiotic tradition. If books ‘transmit values,’ then it is the word that transmits meaning.

Synopsis of Critical Theory

Now that I have hopefully convinced you to read Myers’ text through a structuralist approach, let’s consider exactly what system of signification Myers represents in his work. I would argue, as I will later draw attention to through textual evidence, that Myers' text reflects Peirce more so than Saussure. (Perhaps you’re still feeling lost about semiotics. Don’t worry. Watch this or this. You can even show these videos to your students!).

In the first chapter of Structuralist Poetics, Jonathan Culler outlines Peirce’s classification of signs: “Various typologies of signs have been proposed, the most elaborate by C.S. Peirce, but among the many and delicate categories three fundamental classes stand out as requiring different approaches: the icon, the index, and the sign proper. All signs consist of a signifiant and signifié, which are roughly speaking, form and meaning; but the relations between signifiant and signifié are different in these three types of signs” (Culler 16). Culler, then, elaborates on each category of signs. First, Culler describes “The icon” as that which “involves actual resemblance between signifiant and signifié: a portrait signifies the person of whom it is a portrait not by arbitrary convention only but by resemblance” (Culler 16). Next, Culler compares the icon versus the index on the basis that “In an index the relation between the two is causal: smoke means fire in so far as fire is its cause; clouds mean rain if they are the sort of clouds that produce rain” (Culler 16). Finally, Culler compares both the icon and the index to “the sign proper” in Saussurean terms: “the relationship between signifier and signified is arbitrary and conventional: arbre means “tree” not by natural resemblance or causal connection but by virtue of a law” (Culler 16). Culler argues that “In any system that is more complex than a code ‒ in any system which can produce meaning instead of merely refer to meanings that already exist ‒ there are two ways of thinking of the signifiant and signifié” (Culler 20). (If I’ve lost you, please refer to the diagram above. Talking about semiotics in abstract terms often leads to losing one’s mind). Finally, Culler exemplifies this notion: “One may accept the primacy of the signifiant, as the form which is given, and take the signifié as that which can be developed from it but only expressed by other signs. Or one may start with the signifié by taking any signs which circumscribe or designate effects of meaning as the developments of a signifié for which one must find the signifiant and the relevant set of conventions” (Culler 20).

For the purposes of teaching semiotics, I hope you have achieved three basic understandings from this synopsis. First, according to Saussure, the relationship between sign–word, and referent–real world object or concept, is arbitrary. For example, the word “chair” has no resemblance to the actual object of a chair. Second, Peirce expanded upon Saussurean semiotics by introducing two additional signs in which there is a relationship between the sign and what is signified: the icon and the index. The icon, such as a portrait, actually resembles what it attempts to represent. Therefore, the relationship between the sign and referent is not arbitrary. The index, on the other hand, represents a causal relationship between the sign and referent; for example, smoke equals fire. The last understanding I hope you have arrived at is that the study of semiotics enables us to develop a vocabulary about sign systems that we can apply to our reading of texts. Rather than reading a word on a page as its literal or figurative meaning, analyzing the types of sign systems the characters privilege and utilize enables us to better understand their relationship to verbal and nonverbal communication.

Application

So, now that you (hopefully) have a better understanding of semiotics, let's look to Myers’ text for concrete examples. As I have already argued, language plays a prominent role in the work from the very first page. The first chapter, in which Stuff explains how he met his friends, also heavily relies on the characters’ relationship to words. In this case, Myers focuses on a particular set of words: names. Rather than calling people by their given, arbitrary names, this friend group renames one another to better reflect a quality of the person–Long-head, Fast Sam, Cool Clyde, and Stuff. In this way, their names resemble indices, because there is a causal relationship between the person and what they are called. To be a part of this friend group, Francis receives a new name that better represents him. Ironically, the origin story of Francis’ name is based upon a lie: “Long-head shook his head and looked at me like I was smelly or something. ‘Can you stuff?’ ‘Do you mean dunk?’ I asked. I knew what he meant. I could play ball pretty well, but there was no way I could jump over the rim and stuff the ball. No way. I couldn’t even come close” (Myers 10). The friends decide to call him Stuff, because they believe he can dunk a basketball: “‘We ought to call him Stuffer,’ another guy said. ‘Or how about Hot Stuff,’ Long-head put in” (Myers 11). In this way, their name for Francis is not arbitrary, but rather represents a quality they believe he possesses. It’s easy to assume why Long-head is called such, and we know Fast Sam has his name because he can run fast. Gloria says, “‘Then you run. They don’t call you Fast Sam for nothing, turkey!”’ (Myers 13). Therefore, through their names, the Good People resist the arbitrary nature of the sign proper. In renaming one another based upon causal relationships, the kids understand that indices are more exact and relevant signifiers. Although the names still rely upon words to signify, in renaming one another, the friends resist the arbitrary nature of the sign proper and replace it with words better suited to signify the person.

Myers expresses the preference for an index over the sign proper beyond naming, specifically in the realm of emotion. Stuff reflects, “I never knew what anyone was thinking or how they felt. Sometimes you knew if somebody was hurt or something like that because you could see them crying. Or if they laughed you could see that, but all the in-between things, like not hurting but feeling sad, or not laughing and feeling happy, you couldn’t tell. And since most people most of the time weren’t crying or laughing, you couldn’t tell about them most of the time” (Myers 26). Other people’s emotions, Stuff acknowledges, cannot be determined without an external sign. However, beyond laughing as an index for happiness and crying as an index for sadness, there is not an adequate, physical sign system for the range and complexity of emotion. Despite his overt preference for indices, he acknowledges that it is a limited means to communicate, because crying and laughing only serve to represent two emotions.

Characters continue to grapple with the inadequacy of language to communicate real meaning. Clyde states, “‘Just saying that somebody is dead doesn’t make it any more real. The only thing that makes it real is Mama sitting up at night and reading from the bible and crying to herself. That makes it real”’ (Myers 30). For Clyde, the arbitrary words are meaningless. His mother’s grief, an index for his father’s death, is what ‘makes it real.’ Nonetheless, Stuff and the Good People realize that the only way to truly communicate with one another is through the system of arbitrary language they are inherently tied to use. Even though there is an acknowledgement that speech is limited and inadequate to reveal truth, and indices are preferential, they cannot rely on indices alone to signify meaning. To reveal one’s own and uncover another’s emotion, as Clyde proposes, people have to talk, communicate. Without communication, people’s interior selves, their feelings, cannot be known or understood.

Discussion Questions

How do the character’s nicknames signify them better than their birth names?

What does Myers suggest about how emotion is signified? Why does Stuff privilege laughing and crying?

Why do the Good People still communicate through language, although they acknowledge it is inadequate?

Works Cited

Culler, Jonathan. Structuralist Poetics. Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1975.

Myers, Walter Dean. Fast Sam, Cool Clyde, and Stuff. New York, Puffin Books, 2007.

Wideman, John. “Playing, Not Joking, With Language.” New York Times, 14 Aug.1988, https://www.nytimes.com/1988/08/14/books/playing-not-joking-with-language.html.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Reach of Desire is Forever: Judy Blume and Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet

The Beatles said “love is all you need,” but Anne Carson would say desire is all you have. In reading Judy Blume’s Forever, I often found myself questioning what exactly Katherine and Michael felt for one another. Their relationship goes 0-60 after one, brief conversation at a New Year’s Eve party, and ends almost as fast as it began. So, if not love, what is Forever really about? In their article “‘You Can’t Go Back to Holding Hands.’ Reading Judy Blume’s Forever in the #MeToo Era,” Jenna Spiering and Kate Kedley interpret Blume’s contested work as a “cultural artifact”, of which they view through the theoretical lenses of Critical Youth Studies and Queer Theory (Spiering and Kedley 2). Spiering and Kedley’s article focuses upon reading the portrayal of relationships primarily in terms of sex. However, I would like to introduce another critical interpretation of Forever in terms of how it represents desire. In order to do so, I will employ Anne Carson’s account of eros to explicate the relationship between Katherine and Michael. Departing from Spiering and Kedley’s reading that accounts for Katherine’s first time having sex and being in love, I will read Forever as text that represents Katherine’s first time acting on and experiencing desire.

Synopsis of Critical Theory

In Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet, Carson meditates on eros, or desire, primarily through ancient texts. Carson identifies, “It was Sappho who first called eros ‘bittersweet.’ No one who has been in love disputes her. What does the word mean?” (Carson 3). Using Sappho as her point of departure, Carson then goes on to delineate how and why eros has been represented traditionally in order to detail the qualities and nature of eros. First, Carson considers the implications of translation on an understanding of the term:

“Sweetbitter” sounds wrong, and yet our standard English rendering ‘bittersweet’ inverts the actual terms of Sappho’s compound glukupikron. Should that concern us? Ih her ordering has a descriptive intention, eros is here being said to bring sweetness, then bittersweetness in sequence: she is sorting the possibilities chronologically. Many a lover’s experience would validate such a chronology, especially in poetry, where most love ends badly. But it is unlikely that this is what Sappho means. (Carson 3-4)

Carson, therefore, argues that Sappho did not entail for the connotation of the word to indicate chronology. Rather, Carson insists that the bittersweet quality of eros is simultaneous. Eros involves “splitting desire into a thing good and bad at the same time” (Carson 9).

Then, Carson questions why this is so. In order to do so, Carson draws upon the Greek definition of eros as “‘want,’ ‘lack,’ ‘desire for which is missing.’ The lover wants what he does not have. It is by definition impossible for him to have what he wants if, as soon as it is had, it is no longer wanting” (Carson 10). Desire, thus, cannot be felt for what is present, but only for what is absent: “Who ever desires what is not gone? No one” (Carson 11). Carson posits that eros is predicated upon what is absent: “there is the core and symbol of eros, in the space across which desire reaches” (Carson 25). Ultimately, Carson concludes that eros, as a verb, is this very reach which is “defined in action: beautiful (in its object), foiled (in its attempt), endless (in time)” (Carson 29). Did you hear that? Carson said ‘endless (in time)’ sounds awfully similar to forever to me...

Application

Through Carson’s notion of eros, Forever by Judy Blume can be read as a representation of Katherine’s desire. Throughout the work, the object of Katherine’s desire shifts from Michael, to loss of virginity, to Theo. Katherine’s desire is never consistent or stagnant. Akin to Carson, Katherine demonstrates that desire is a state of being that can never be fulfilled. Desire is predicated upon an absence of that of which is desired. Once it is fulfilled, it ceases to be desire. Therefore, Katherine’s desire is always beyond what she currently possesses.

In Forever, Katherine first feels desire for Michael. Similar to Carson, Blume exemplifies desire through the action of reach. When Katherine initially meets Michael, she thinks, “He wore glasses, had a lot of reddish-blond hair and a small mole on his left cheek. For some crazy reason I thought about touching it” (Blume 2). Katherine expresses desire to touch Michael, to reach towards what she desires. The desire is reciprocal, as Blume also depicts Michael’s reach towards Katherine: “‘Look…’ and grabbed my wrist. ‘I came over here because I wanted to see you again”’ (Blume 6). According to Carson, in this moment, Katherine and Michael’s desire for one another would cease to exist. The reach is met with contact: “He was still holding my wrist” (Blume 7).

Although Katherine and Michael’s desire to date one another is quickly expelled, given that they do begin to date one another, their desire then reaches towards a different end: having sex. Blume continues the motif of the reach to depict desire: “If Erica and Artie hadn’t been there I doubt that I’d have stopped Michael from unbuttoning my jeans,” and “We lay down on the rug and after a while, when Michael reached under my skirt I didn’t stop him, not then and not when his hand was inside my underpants” (Blume 28, 50). Katherine’s desire to have sex depends upon the fact that she has never had it. Her desire is for what she lacks, what is absent. Katherine wonders, “What would it be like to be in bed with Michael? Sometimes I want it so much–but other times I’m afraid” (Blume 52). Blume employs the dash as a means to syntactically represent the reach of desire. The dash, like desire, extends towards something beyond. In this instance, Blume portrays the paradoxical nature of desire, as something which Katherine ‘want[s] so much,’ but is also ‘afraid’ of. Blume continues to use the dash to convey Katherine’s desire: “I wanted to do everything—I wanted to feel him inside me” (Blume 102). Katherine finally decides she is ready to have sex with Michael, to fulfill her desire. Her desire reaches towards the end of itself. Once Katherine has sex with Michael, and her desire is attained, she is met with disappointment as her desire ceases to exist: “‘Everybody says the first time is no good for a virgin. I’m not disappointed’ But I was. I’d wanted it to be perfect” and “I’m glad—I’m so glad it’s over! Still, I can’t help feeling let down” (Blume 106, 107). Katherine’s internal conflict represents the irony of desire: once one has achieved what they thought they wanted most, they no longer want it.

Ultimately, Katherine’s fulfillment of desire for Michael and to have sex inevitably leads her to desire beyond him. Once Michael no longer is an absence for Katherine, in terms of a boyfriend and the opportunity to lose her virginity, she no longer desires him. In the letter she never sends to Michael, Katherine confesses, “I’ve met someone who’s got me very mixed up. No, that’s not exactly true. I mean it’s true that I’m mixed up, but I can’t blame him for that. I know this is very hard for you to understand. It’s hard for me, too. I made promises to you that I’m not sure I can keep” (Blume 199). Katherine herself does not understand her own desire, but nonetheless she realizes that her desire to be with Michael is obsolete. Katherine can no longer promise to be with him forever. Her reach towards Michael has been met, and her hand extends beyond him: “Theo and I were standing side by side, both of us dressed in cut-off shorts, him with no shirt and me in a halter, covered with sweat, smudged with dirt and still holding hands, which we dropped immediately” (Blume 200). Katherine’s inclination towards Theo has nothing to do with Michael himself, but only reflects the nature of desire: “‘Look,’ I told him, ‘it’s not you. You haven’t done anything … it’s me… it’s that… well…” (Blume 203). Katherine’s desire for Michael can no longer be, because it has already been fulfilled. Once desire has been fulfilled, it no longer is desire. Thus, Katherine’s desire reaches towards that which she does not already possess. Due to this, Katherine’s desire is never satisfied in the text–her desire always reaches beyond.

Through Carson’s notion of eros, Forever is not a representation of first love, loss of virginity, heteronormative relationships, or second-wave feminism reproductive health rights, but of the reach of desire. In Forever, Blume exemplifies Carson’s notion of the reach of eros as ‘endless (in time)’ through Katherine’s various desires throughout the text. Despite the fact that Katherine and Michael’s relationship ends, she is no longer a virgin, and her relationship with Theo will likely expire, Katherine’s desire is forever.

Discussion Questions

To what extent does Forever exemplify Carson’s conception of eros?

How does Blume portray the reach of desire?

What does it mean to read the text as a representation of desire rather than love?

Works Cited

Blume, Judy. Forever. New York, Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2014.

Carson, Anne. Eros the Bittersweet. Champaign, Dalkey Archive Press, 2009.

Spiering, Jenna and Kate Kedley. “‘You Can’t Go Back to Holding Hands.’ Reading Judy Blume’s Forever in the #MeToo Era.” Study and Scrutiny: Research in Young Adult Literature, vol. 3, no. 2, 2019, p. 1-19.

1 note

·

View note

Text

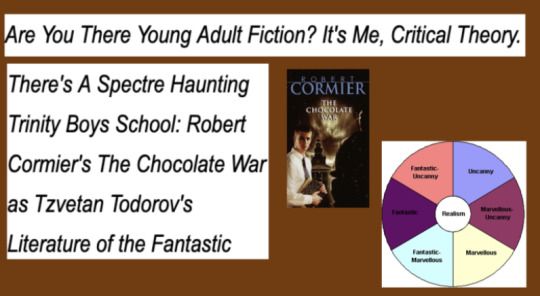

Is There A Spectre Haunting Trinity Boys School? Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War as Tzvetan Todorov’s Literature of the Fantastic

People accept generic classifications without considering how conventions, and our assumptions about such conceptions, radically influence our reading of a text. If you’re having a hard time accepting such a fact, just consider if the Bible was read as historical fiction, dystopian, or fantasy. Your readings of the characters, events, themes, and author’s purpose would be radically different. To illustrate this further, I will provide a reading of Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War as a gothic text.

Reading the novel in terms of its generic potential is not unique to me. In fact, in Yoshida Junko’s article, “The Quest for Masculinity in The Chocolate War: Changing Conceptions of Masculinity in the 1970s,” Junko classifies Cormier’s work as a quest narrative in which “a young man seeks a masculine identity” (Junko 106). Junko argues that Cormier “is daring enough to portray the all-male world as bleak, to find fault with traditional gender roles, and to depict his protagonist, Jerry, as seeking a new male identity” (Junko 106). Junko’s analysis emphasizes how classification of genre profoundly influences interpretation of a text, its characters, its outcomes, and an understanding of the author’s project.

Therefore, similar to Junko, I propose a reading of The Chocolate War based upon genre in order to offer a nuanced interpretation of the work. However, I do not propose the text is a quest narrative, but rather a gothic text. Through Tzvetan Todorov’s theory of the fantastic, I will consider the implications of the gothic genre on Cormier’s project to represent adolescence.

Synopsis of Critical Theory

Now, to be even more specific about what I mean by “gothic,” let’s look to Tzvetan Todorov. In chapter 3, “The Uncanny and The Marvelous,” of Todorov’s The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to Literary Genre, Todorov establishes the basis for his argument, as he distinguishes between the marvelous and the uncanny as literary genres. Todorov defines the uncanny as that of which “the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described” (Todorov 41). On the contrary, the marvelous, according to Todorov, is that of which “new laws of nature must be entertained to account for the phenomena” (Todorov 41). Todorov states his thesis: “The fantastic therefore leads a life full of dangers, and may evaporate at any moment. It seems to be located on the frontier of two genres, the marvelous and the uncanny, rather than to be an autonomous genre” (Todorov 41).

Todorov substantiates this claim by depicting trends in gothic criticism when he asserts that the trend has been to classify the literature into two camps: “that of the supernatural explained (the ‘uncanny’)” and “that of the supernatural accepted (‘the marvelous’)” (Todorov 41-42). Thus, in reading gothic novels, the fantastic, as a literary genre, is put into a state of disarray because there is a clash between the uncanny, the marvelous, and the fantastic as genres. Despite the instability of the fantastic as a genre, Todorov notes that we must remember Louis Vax’s “remark that “an ideal art of the fantastic must keep to indecision” (Todorov 44). Therefore, Todorov proposes that instead of reading novels purely as fantastic in genre, that one read them for their subgenres as well: that of the “fantastic uncanny” and the “fantastic marvelous” (Todorov 44). Todorov’s argument is significant because it reshapes the fantastic as a genre that includes two subgenres. In doing so, Todorov not only redefines the fantastic but also emphasizes the importance of the uncanny and the marvelous to the genre. In short, the gothic can be put into two camps: the supernatural explained or the supernatural accepted.

Application

What camp the work aligns with is essential to understanding and interpreting its gothic elements. Dracula is not a text about an eccentric man who drinks blood, but it is about a vampire (supernatural accepted).

In reading Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War as a gothic or fantastic text, it is essential to decide whether it is representative of the ‘fantastic uncanny’ or the ‘fantastic marvelous.’ This reveals both the nature of the supernatural events of the text–explained or accepted, and the implications this has on the work as a whole. If for instance, The Chocolate War is read as the fantastic marvelous, then Jerry’s mother actually becomes his father, Jerry actually hears the voices of ghosts, and Jerry actually becomes invisible (Cormier 59, 207, 213). However, this is not the case. In each of the aforementioned instances, Cormier offers an explanation for each of Jerry’s encounters with the supernatural–a trick of his imagination, the Vigils are hiding in the bushes, and everyone at the school decides to ignore Jerry: “The kids are giving Renault the freeze” (Cormier 215). In reading The Chocolate War as the fantastic uncanny, the work is able to take on nuance as a gothic work: the supernatural is explained. The Chocolate War is not a text about Jerry being haunted by ghosts as a consequence for his resistance, but about the hallucinations that such a fear of breaking the status quo provokes. Therefore, it is not the supernatural that makes Jerry’s experience so horrifying, but the experience of his everyday life. It is the supernatural explained that emphasizes the terror of adolescent existence.

Discussion Questions

Is The Chocolate War that of the supernatural explained–uncanny fantastic, or the supernatural accepted–marvelous fantastic?

How do Todorov’s categories within the gothic genre serve to enhance or clarify your reading of The Chocolate War?

What implications does reading the text as the “fantastic uncanny” have on your interpretation of the narrative? On Cormier’s project?

Works Cited

Cormier, Robert. The Chocolate War. New York, Ember, 2014.

Junko, Yoshida. “The Quest for Masculinity in The Chocolate War: Changing Conceptions of Masculinity in the 1970s.” Children’s Literature, vol. 26, 1998, p. 105-122. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/chl.0.0352.

Todorov, Tzvetan. The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre. Cornell Paperbacks. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1975.

1 note

·

View note