Hello Readers! My name is Anna, I'm a student at the British Columbia Institute of Technology, a worker at a local game store and a lover of games, art, science, fashion, coffee and many, many other things.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Exploring flow in Levelhead

Mechanic Introduction

During the first level, the game introduces its core mechanics through signs posted in the background of the scene. It is a pretty standard method to display information. Text and pictures are the most common way information and directions are given to people, and their use in games has become widespread. However it is a rather uninteresting way to do so, and some instructions are still unclear. This is especially true for elements that are more complex to understand.

A more interesting technique is to let the player naturally explore elements. The game does this very well with some mechanics in the first level. The first time the player encounters a spike ball, it's almost completely protected behind a wall. However there is an opening, allowing the player to interact, and subsequently die, at their own choice. Even though most players will understand that spikes are the main adversary of the side scrolling protagonist, it still leaves room for the player to find by their own choice.

Other examples of this kind of player involved experimentation is the first moving enemy. The first enemy the player encounters is safely blocked by an obstacle, giving the player their own time to absorb what they are seeing and allow them to interact with it as they see fit.

Even when the player picks up the box for the first time the game does something rather elegant. The player's first instinct after pressing the key to pick up the box, is to press that key again and see what happens in this new game state. The player will conveniently be positioned most likely directly across from a button they’d have to place this box on anyway. So the player will pick up the box, attempt to use the same key, and throw the box exactly where it will give them the most useful information as soon as possible.

Discernibility

The game offers plenty of feedback to their actions. Crystals pop in engaging ways, enemies burst and the player character will change appearance depending on any power ups. Most enemies are signified by mobility or bright colours making the measly distinguishable. In fact almost all elements of importance will have some amount of movement to their visual design, which instantly makes them stick out to other players.

Excitement

The game is usually highly focused with individual levels ranging in time and difficulty quite significantly. This creates a lot of different flow experiences per level, with some ranging from mostly high intensity to some only being a short breeze and mechanic introduction.

Down time within a level consists of the in between play space between individual challenges. The game relies on several obstacles lined up one after another, and while some are extended experiences of high intensity. The game sometimes utilizes extended sequences of unknown high intensity, where the player can only keep going forward. This can create a good sense of flow, however it does also remove player agency. After the player fails this challenge once, its basically lost all of its possible interest.

The level ouch cart in particular features an extended challenge of high intensity with no downtime at all. The platform constantly moves, and several buzz-saw's surround the player at all times. The level also offers several opportunities for the player to attempt high risk, high reward challenges with collectibles being off to the side of the platform. All together this is nonstop high intensity with very little downtime. In fact the downtime only comes after each failed attempt at the run, but it is more than likely to make players jump back into the action quickly regardless of this possible down time because it is in the players hands. If the player is already running on high anxiety, it is much more difficult for them to take time to slow down, since their brain is already higher on the anxiety scale.

However; not all levels provide the same amount of constant high intensity. Some levels are much slower, and rely almost on a puzzle-esque approach to get past. These levels in themselves provide downtime to the overall experience. Although they come off as pressing the breaks, rather than as a natural lowering of intensity.

Rest

The primary down time is experienced between levels in a given session, and gives the player opportunities to explore other zones or custom build their own content. Even the menu has a nice flow to the level selection screen, as the little ship that is used as your cursor icon floats between nodes and it in itself is fun to attempt to navigate the menu in as fast a time as you can without messing up the ship's path. It does make selecting levels more time consuming, but it is very engaging in its own way.

The level Crypt of the Watcher includes a fairly prominent example. In it, the player is faced with several switches, colours and platforms. The player must change the switches to the colour as shown overhead. However it feels less like a natural expansion of gameplay and merely a detour away from a challenging aesthetic.

Personally Levelhead is an example of a game that fails to get me into a state of flow. While the gameplay elements lead the player well, its aesthetic choices usually keep me bored or frustrated. The game offers very little incentive to keep me playing, given it has no interesting world, characters or story, nor does it attempt to even draw on a certain emotional output (beauty, fear, etc.), it merely exists to create challenges, and that rarely gets me into a state of flow.

While I do not personally find the flow of Levelhead engaging to me, it is still an excellent example of how flow is achieved. Between high intensity levels, collectibles and even a cute story, comes a game that does make the player want to solve and complete each task before them. GR-18 has got a pretty good chance of capturing an employee who will engage with and utilize his abilities to the best of their effect.

0 notes

Text

A Discussion of Battle of Polytopia's Interactivity

Battle of Polytopia is a mobile 4X strategy game. This discussion will focus on how Polytopia supports the pillars of interactivity and choice with the player. Explicit interactivity involves the most direct form of choice, cognitive interactivity surrounds emotional and intellectual effects of a game, and functional interactivity is the utilitarian, physicality of the game's interactions.

Explicit interactivity

The game offers many forms of explicit interactivity. Moving units, creating buildings, researching technology and attacking enemies are all examples of explicit interactivity.

Moving Units: Moving units from one tile to another is one of the most common forms of interactivity the player utilizes. The player chooses a unit to move, the game provides the spaces it can move to, the player chooses a space, and the game reveals places on the map or otherwise gets that unit closer to a desired destination.

Creating Buildings: The second most used explicit interaction in the game, building structures and exploiting resources is key to playing. The player selects a tile, the game offers the possible actions they can take on that tile, the player chooses the option they would like (or no option at all), and the game places the building and awards stars, population or score.

Researching Technology: Another important decision is choosing what technology to research. The player selects the technology button, the game presents the web of possible research options, the player chooses one they would like (or nothing), the game displays what the player will get for researching the technology, and if the player confirms it the game changes the research icon to represent that it has been researched, reveals future possible technologies and awards the player with the bonuses it offered.

Attacking Enemies: Another possible aspect of the game is combat. If a player moves their unit close to an enemy unit, an option will appear if they want to attack. Should the player accept that invitation, their unit will deal damage and receive damage, as notified by small floating numbers, and then the player's unit may take the place of the other unit if it was destroyed.

Upgrading Cities: This one is fairly common, however it's prolly one of the weaker points. While it is certainly integrated in the largest game plan of the player, it's actually not very discernible. Neither me nor my other multiplayer companion could actually tell what some of the bonuses were, especially given that there are no text descriptions of the bonus. Examples like gaining 5 stars, or border expansion are relatively easy to understand. However the park option in particular is very cryptic. After choosing it, you gain no population or stars, and there seems to be no immediate bonus.

These say very little about what they actually do.

Cognitive interactivity

The game's cognitive interactivity relies most heavily on grand strategic planning. However there is also interactivity in moments of triumph over another empire, satisfaction or disappointment with your score, and more micro strategic decisions as well.

Grand Strategy: As this is a 4X game, its primary means of cognitive interactivity is in grand strategy. The player is always thinking about where to build buildings, when to build units, who to attack and where to expand. This constantly evolves as the player progresses, and as each explicit interaction garners new information or effects, the grand strategy evolves and changes, and the player develops new plans, and as those plans execute, successfully or not, so too does the grand strategy continue to develop.

Inter-player Competition: One of the more specialized forms of interactivity is the unique challenges and interactions that the multiplayer mode offers. Other players are both more challenging and more unpredictable, and the competition that arises between two human players creates a whole new level of interactivity. One player will execute a strategy and so the other player has to adapt and overcome, to which the first player must then also react to.

Inter-player Dynamics: On the other side of the multiplayer coin, is the less intellectual side of emotionally connecting with another person. This is even more niche as this requires a more intimate connection than just having two players compete without ever talking with one another. However it does do a lot to change the way the game is played in a very positive manner. Jokes arise, vengeances are declared, mockeries are made and the focus can sometimes shift from winning altogether into just enjoying the company.

This was our first multiplayer match. I think the names alone give a pretty good idea of how we enjoyed the game.

Creativity: One of the least talked about aspects of strategy games is the creative influences that make a player engage with the game. A player can enjoy the game solely on its ability to create an interesting world for them to develop. Creating stories, culture, unique names and all kinds of special interactions to create a special connection to one's expanding empire.

Ending A Game: Partially an emotionally driven aspect of the game is the final outcome, as well as the drive to win. It provides both a sense of loss or victory depending on how well you devised your overall strategy, and gives the player a chance to reflect on what they did right or wrong, and how they can improve their strategy or how they would like to play differently (On a bigger map, with less people, as a different empire, etc.)

Functional interactivity

Most games feature a significant amount of functional interactivity, given that games are built out of functional components. Some interesting examples to discuss include button sizes, text sizes, the drag sensitivity, among others.

Screen Orientation: One of the first most noticeable interactions is the screen orientation. If it is vertical, the camera is more zoomed in, and obviously has more vertical space. If it is horizontal, the screen is wider, everything is further out, and there is more horizontal space. Given that the bottom and top margins have the same depth of darkening area, the horizontal screen actually has less screen space overall.

Drag Sensitivity: Moving the screen around is the most common action the player will perform. Luckily the action is crisp, follows the player's finger closely, and offers a fair bit of skating when the player lets go at high speeds.

Text Size: Not a particularly interesting topic, but an important one nonetheless. The text is readable, and is always featured as white on black, so it keeps it very clear. If the text was not clear this could very easily ruin the whole experience, given how much it relies on explaining core elements and features of the game.

Screen Zoom: One of the strangely lacking features from this game is the inability to zoom in or out. Given the small screen size, it would have been beneficial to be able to scope in on smaller aspects of the empire, and I found myself attempting to perform a zoom multiple times to no effect. It is something that just feels like it should be there, and the fact it lacks it is very immersion breaking. It may not even be that useful, but it just feels natural to expect that to work.

How well is interactivity supported

Battle of Polytopia is an excellent example of supporting interactivity. Its elements are usually well conveyed and its array of choices all bleed into each other effectively. Aspects from one mode of interactivity usually support an aspect from another mode, and so on.

Each interaction involving a player's units supports the overall grand strategy, as each micro decision plays into a macro one. And the grand strategic planning plays into how well players emotionally become invested in their empire, the other player they are playing with, or their win/loss condition. The screen orientation affects a players ability to make decisions, the text size ensures technology bonuses are clear, etc.

Battle of Polytopia is a fun 4X strategy game, and like its cousins in the genre, it does a great job investing players in their empires success and development, making micro strategic decisions meaningful and interesting, and displaying information in the most effective way that it can manage for the limitations of a mobile device. Overall Battle of Polytopia does an excellent job supporting player choice, and is a first class representation of its type in the mobile market.

0 notes

Text

Does Kingdom Rush Engage its Target Audience

Kingdom rush is a tower defense mobile game. I will be discussing both the target audience Ironhide Games was attempting to reach, as well as their effectiveness at engaging that audience. Each aspect of the audience reveals a different facet of the game's design that complements each other. For this reason, Kingdom Rush does an excellent job at engaging its target audience.

Target Demographic

The most direct way to address an audience is through common demographic profiles. Its accessible gameplay and strategy focus allow for almost anyone to enjoy, so long as they are capable of keeping up with the somewhat fast paced nature of the gameplay. Kingdom Rush primarily targets younger audiences, but is certainly not exclusive to older players as well.

The main part of the aesthetic that drives this target audience of younger players is its visual design. The visuals are evocative of comics or cartoons. The design looks hand drawn and the colours are bright and distinct. There is also a distinct lack of obscene content, a necessary part of any game targeted at younger audiences.

Unfortunately the visuals do present as bland and generic. Whether more recent than kingdom rush or not, the hand drawn, cheeky medieval fantasy world has been used in several other games. Clash of Clans is a similar example, and Castle Crashers also has a very similar visual aesthetic, but at least has a more crude and adult spin to it. Even another tower defense game, plants vs zombies is filled with bright greens and simple cartoon characters.

Additionally, some might say the game could favour a male audience given its focus on violence. It also primarily features male characters (The king, ten of the twelve heroes, and the villain are all male). I would however disagree and say this game is very open to both genders regardless. The game is a fantastical setting that doesn’t really lend itself to either gender regardless of the character make up.

The 4 axis of the Myers Briggs Personality Index can also be used to establish the kind of audience that would enjoy this game. The first index measures introversion vs extroversion. Given that this is a single player game, it will naturally appeal to introverted players. The second index is how people direct their energy, between practical observants or open-minded intuitives. Given the game's more rigid rules and strategic focus, it caters toward observant people. The third index is whether a person is more thinking, or feeling. Again, given the focus on player strategy and less on any kind of emotional stream, it's safe to say it also caters to thinking individuals. And finally based on whether people are better at being organized or better at improvisation, judging or prospecting respectively. This last one is tricky, and I think both are valid personality traits to cater to in this game. However it is again focused on a grand strategy and will more likely favour judging people.

Most other demographic indicators have no real bearing on the target audience. Race, ethnicity, occupation etc. are not a focus for the creators of the game. In this way the game is targeting as broad a spectrum as possible, a fairly common practice in the games industry.

Hardcore or Casual

When it comes to most games, a lot of emphasis is placed on hardcore or casual player markets. Most mobile games are targeted toward a casual audience. Mobile games are easier to pick up and put down, they are much more accessible in someone's daily life, and play sessions can be just as rewarding in short bursts.

This naturally brings us to Kingdom Rush’s primary aesthetic. Generally, Kingdom Rush follows its siblings in the mobile market with a submission aesthetic, however it is not completely divorced from the challenge aesthetic either. It is mostly focused on shorter gameplay sessions, and is relatively short to finish the main campaign, 12 missions at roughly 20 minutes each.

However, one of the more ineffective aspects of engaging a casual audience in their design is that each mission does take a while. While playing I had several instances where I had to leave part way through a mission and accidentally closed it shortly after. It may have been more effective to allow players to save the mission they’re in, so that people with very short time intervals can leave safely.

The other aspect primarily focused on casual players is the limited control scheme. The player doesn’t need quick reflexes or fine motor-control, they only need to place towers, which are laid out in a very clear and discernible manner.

Bartle Player Type

The primary Bartle player type that Kingdom Rush caters to is the Achiever. Given the complete lack of other players, it is essentially irrelevant to socializers and killers. While the explorer will only be confronted with few wonders or surprises outside of new levels, enemies and towers. However this game is perfectly catered toward achievers.

The driving factor of most achiever players is quite literally to achieve, whether high score, upgrades to your ‘character’ or simply mastering a game's mechanics. Kingdom rush offers all of these and more to players. Below is just a snippet of all the different aspects that would intrigue a player looking for that 100% goal.

Some things that the game offers:

The game rewards players stars for completing a level while taking minimal damage.

Crystals are also awarded for defeating tough enemies.

Stars and crystals can be spent to upgrade your army and buy items.

The game has many levels, including a main story end point.

Each level has additional challenge modes to complete.

Achievements are offered as cross level challenges.

Special heroes are unlocked throughout the game.

Players directly act on the game's world in each level.

All of these elements give a player plenty to achieve. In terms of player advancement, level progression and score keeping aspects. This is another common trope for many mobile games, offering many smaller rewards to keep players coming back. A feature that ties back around to casual players, as both the achieving aspects of the game complement the casual nature.

However the Bartle player personality test doesn’t encompass enough of their target audience. Just because the player is motivated by achievements doesn’t embody what the target player is engaged in while playing the actual game. So we will also discuss:

DGD1 Classification

The primary player behaviour that Kingdom Rush targets is the manager archetype. The game does offer a challenge for conqueror players, but rarely offers a truly difficult experience outside of the later game side content. The wanderer will be drastically left without any sense of exploration or wonder. Meanwhile the participant has no story, characters or cooperative experiences to entrance them.

The manager however is driven and engaged with content that challenges them, while allowing for a unique strategy to each player. The game is decently deep with its mechanics, and allows for a large variety of different playstyles, strategies, or just favourite towers. Players may put several barrack’s right outside the entrance, or just line every path with cheap archers.

The game creates a whole host of dynamics for the players to experience. There are numerous different ways to place your soldiers, set up your towers and use your abilities. Each of the 4 towers has 3 levels before the player can choose a specialization for their tower, and each specialization has 2-3 additional upgrades. Despite this possibly low count, it is very impressive how deep the game becomes with this limited toolkit.

Below are two different layouts for towers that each offer their own unique bonuses and cater to different strategies.

This strategy focuses on creating a chokehold with a barracks near the entrance. The barracks keeps the enemy next to towers to deal more damage. The left regularly spawns demons, enemies that quickly dispatch your own soldiers due to damaging them when a demon dies. So a ranger tower with poison is placed to deal with the enemies that dispatch the soldiers more quickly. Meanwhile the right side features more heavily armoured black knights. So complement that with a sorcerer tower to weaken the knights armour, while an artillery deals area damage to the attackers that are stopped at the chokepoint. Unfortunately this strategy is weak to flying units, as they bypass the barracks and the artillery with ease.

This other possible strategy focuses on high damage towers to dispatch with enemies as quickly as possible. The rifle tower can get hits on enemies much earlier than any other tower, and is placed early to complement this. This strategy also deals with flying enemies much more effectively, as they get eviscerated very quickly by the much larger array of damaging towers.

Engagement Justification

Each profile above describes a different key aspect of the game, one Ironhide has done an excellent job of mixing with each other.

The game is simple, and can be enjoyed in short play sessions. An aspect that works incredibly well for casual players. These short play sessions also allow creating rewards to benefit those smaller play sessions. Something an achiever will absolutely adore as they are showered in stars and crystals for each level. But it also allows for each level to be a microbiome of strategy. Manager players are not just focused with a grand overarching strategy, but instead every level is its own puzzle, albeit a puzzle with many different answers.

The fact that each level can be completed with different strategies doesn’t just complement the manager either, but also complements the casual player. It allows for a minimal pressure environment of no-wrong answers for casual players. And then another aspect; managers maximizing their strategies in order to get more rewards as an achiever.

All of these target audience profiles focus on players who enjoy small, short challenges, with rewards they can strategize with over their experience with the game. Casual players can have a sense of progression through stars, achievers will be able to collect all of those stars, and managers can spend those stars wisely.

The game offers several different difficulties for each mission. The different difficulties complement multiple different parts of the target audience. The easy difficulty allows casual players to progress much faster than if the game was strictly more difficult, essentially creating more content from their time spent. The medium difficulty appeals to the manager archetypes that want to figure out an effective strategy in the deep pool of tools the game offers. The hard difficulty also allows those managers and the achievers to maximize their strategy and get the most recognition.

I could go on and on. This game doesn’t focus on one player profile, but instead several, and maximizes the efficiency of engaging each and every one of those players. So it is safe to say this is certainly a game that knows how to engage its audience, all of them.

0 notes

Text

Does Once Upon a Tower Facilitate Meaningful Play

Once Upon a Tower is a mobile game in the mould of an endless runner, that I’ve been playing on and off the last two weeks. It's got a fairly addictive loop and some interesting concepts regarding its core topic of princesses. My objective here is to discuss how this game facilitates meaningful play.

Core Loop

The core loop of once upon a tower comes down to planning the path you’re going to take, moving to execute that plan, and then dealing with the obstacles on that path.

Planning Your Path: The first aspect of the loop requires the player to observe her surroundings. Which blocks can I break? Where are the enemies? Are there any fireflies? The game is very deliberately laid out in a single flow path, where the character can only go down, which creates a linear force on the player, and doesn’t leave things as open ended as in a multi directional movement system. This makes planning your path essential, but also very simple and easy to follow for players.

Moving: Next the player has to attempt to execute her plan. Usually by moving into a potentially dangerous situation or taking an unknown leap of faith. Either way the player needs to start swiping and execute her course of action.

Solving Obstacles: While planning and moving are the bread and butter, once you encounter an orc or a fireball then you need to move from passive planning to dexterous action. You need to swing your hammer at the right time, or move out of the way fast enough. The difficulty of the game relies on the precise timing of this step in the loop.

Mechanics

The core mechanics of Once Upon a Tower are: Move, smash with hammer, gravity, a grid space, breakable and non-breakable platforms, and an obstacle. An interesting aspect of this game is its very simple control scheme. The player only needs to swipe in one of four directions for all of the interaction in the game, from moving, to hitting enemies, to buying items, it all relies on the direction you swipe. If you’re swiping toward an open space, you simply move. If next to an object, you hit it with your hammer.

Move: Moving is the most direct mechanic of them all. Merely move your character from one place, to the next place.

Smash: If the player swipes against an object, then that object is destroyed. There’s no health, or conditions. If you’re adjacent to it and you swipe it, it is removed (assuming it is an object that can be.)

Gravity: If the character has nothing underneath it, then she falls. She will keep falling until there is something underneath her.

Grid Space: Everything on the map is laid out in a grid. The map is only a certain amount of tiles wide, and every object takes up some amount of tiles (usually only one). The player’s movement is strictly tied to this tile setup, and will always have a position related to one of these spaces.

Platforms: The player needs to stand on something, and she needs to be able to change her environment somehow. If the player had no platforms, she’d fall forever. If the player only had invincible platforms, the player would merely be navigating a narrow path with no effect on the game in any discernible way.

Obstacles: The final ingredient is the challenge. The player needs something to actually test their skill. The game features several different obstacles, but it only really requires one. Be it a roaming orc, a crawling spider, or even the moving pistons.

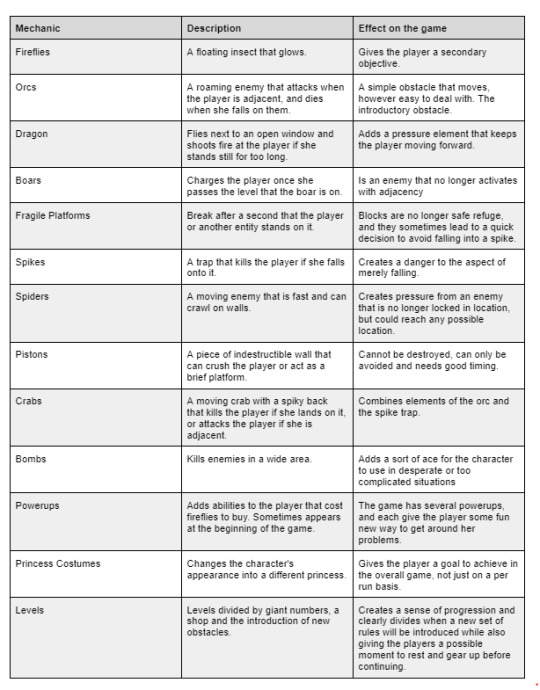

Other Mechanics

I will create a quick table of all the additional mechanics I could think of, with a brief description of each and how they interact with the core mechanics.

There are more mechanics in the game, however this should give a wide range of the types of concepts that are introduced. Each additional mechanic feeds into the core loop and its core mechanics. The spikes and crabs make gravity more stressful, fireflies add a new way to approach formulating your plan, items add more ways to solve problems. Planning becomes more strategic and varied, moving becomes more dangerous and distinct, and obstacles become more difficult and unique.

Meanwhile there are a few mechanics that tie each run in the game together. The princess outfits create a reason to build up those fireflies. The high score gives players a reason to go as far as she can in each run and compare themselves to how she’s gotten better.

Dynamics

While I described some minor dynamics that arise from each of those added mechanics, there are larger scope dynamics that arise when all of these are put together and the most important one that informs most of the game is: what the player wants to accomplish with each run? This question gives rise to additional dynamics, but it will always come back to this question. The answers I found are: Wanting to get the most fireflies or wanting to get as far down as possible. Once the player has decided which she’s gonna prioritize for a run, then all further decisions come back to this idea.

Firefly Collection: If the player decides to collect as many fireflies as possible, either for a better high score or for more princess costumes, then there are several dynamics that arise from that goal.

First, when the player is acting on that first part of the core loop, she is probably going to plan her path toward as many fireflies as possible, and killing as many enemies as possible. The player's path should lead her as close to the danger as possible, because usually that’s where the points lay.

Furthering that, the player will end up playing a slower, more calculating game. She’s going to need to be close to the enemies anyway, so she’ll have to play it safe to survive and collect.

When it comes to items, she may tend not to buy anything because she only wants to collect as many fireflies as she can. Even if it might help her in the long run, it might seem better to hoard as much as possible.

Getting Further: The other option for the player is to ignore fireflies and focus on getting as far down as she can.

Instead of planning for fireflies, the player will plan for safety. Instead of risking anything, you’re going to avoid as many enemies and obstacles as possible. This dynamic I think is somewhat unfortunate, since it prioritizes avoiding fun.

Items in this player’s case are not something to be ignored. If you have fireflies, then you might as well spend them on boots to avoid those dastardly crabs. Or bombs to use for areas that might be too difficult to avoid.

Of course these two primary dynamic choices are not mutually exclusive. It should be noted that getting further down does increase your firefly count usually. And maybe a player is only going to risk it for some fireflies, the ones that are easier. Maybe the player will spend some money on boots because she thinks it will pay off in the long run more than anything else.

Aesthetics

The aesthetics of this game focus on a casual and friendly experience. The visuals evoke cartoons, the sounds are simple and the pace is tailored toward people with only a few minutes to spare at a time. The emotional draw is from passivity, the slightly engaging interaction from a simple world with simple themes and ideas.

Sensory: The game is pleasant enough to look at. Its characters are simple, low polygonal models of princesses and fantasy creatures. It features bright colours, which gives the game a sense of pop. This colour scheme was designed to ensure the player can always follow what is going on, what she needs to look for and what she needs to avoid. It's no accident that the most bright objects are the moving fireballs. Elements that would be the hardest to track.

Genre: The genre I think most accurately describes this is platformer. It is always progressing in a linear direction, there is a distinct lack of a “realistic” flow of the level design, and of course the character literally uses platforms throughout the game.

Emotional Response: This game primarily focuses on submission. Submission arises from a more simple experience. It is focused on a player base that does not have a lot of time or thought to be put into their games. Its goal is to induce a sense of repetition, which is enforced by repetitive gameplay, and a lack of complex decision making. This is usually the primary emotional response all mobile games tend to evoke.

Narrative and Themes: The game has a simple narrative. The player is a princess stuck in a tower, about to be rescued by a noble hero, before he is burned to a crisp. He drops his hammer into the princess's room and the princess decides to save herself for once. The game likes to advertise the last fact. Its central theme is promoted around this flipping of the traditional roles. It never delves into anything deeper with this rather distinctive feminist theme, but it is a feminist theme nonetheless.

Meaningful Play

The idea of meaningful play revolves around its two components. Are the actions in this game discernible and are they integrated. This game's actions are both easily discernible and adeptly integrated. However, I do not find it provides as much of a meaningful gameplay experience.

Discernible: As discussed Once Upon a Tower has a very simple interaction with the player. Swipe to move or smash. When the player swipes, you know exactly what is going to happen, cause there’s only two things that could happen. The player moves to a new tile or removes an obstacle from the game. When a player picks up an item, the character changes appearance slightly. When the player grabs a firefly, it flashes the top right corner and increases your count. All of the actions are easily discernible and remarkably identifiable.

Integrated: While the game is certainly discernible, the integration is harder to nail down. On a single run, it is integrated, you move down, enemies are removed from the game permanently, items stay with you until you use them, and failure means your game is over. Between the individual runs, the primary connecting tissue is your firefly score, and the princess costumes. Given a run that only lasts about five minutes, the integration is an aspect that feels weak. This isn’t anything new, most mobile games are designed with minimal integration for a grab and drop play session experience.

Why it isn’t meaningful (To me): I personally don’t find this game very meaningful. It has a certain lightness to it. A lack of depth, akin to watching sitcom reruns. The idea of integration to me should go beyond the scope of players actions impacting the game state. While it certainly reaches the mark for a game that can be mildly entertaining, I find it hard to find any investment in it, to actually derive meaning. I’ll address the target audience for this, because obviously, it doesn’t seem to be me.

This game never provoked any emotional response from me, never builds anything that made me strategize, nothing connected me to this world, nothing made me think or feel. If integration doesn’t include what a player takes away from a session, doesn’t rely on the thought or emotional response of the person interacting with it, then its integration is still meaningless.

Why it is meaningful (To other people): This game does provide meaningful play to some people. It’s audience was meant for people who only have spare minutes between their daily life. It was not created as high art meant to be thought about for years, and some people can find meaning in those simple pleasures. The integration is only important in those short moments, and building up to a high score or new costume can provide meaning to people who really enjoy those elements. What the game does well is create a short little adventure for somebody's favourite princess character, and that is certainly meaningful to somebody.

0 notes