Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Plant Blindness, Plant Script, Plant Co-Authorship and Interspecies Dialogue

By Amy Gowen

The neglect and dismissal of flora is not only limited to scientific outlooks but extends also to social and cultural domains with planets often being reduced to just aesthetic purposes. Alarmed by the relegation of threatened floristic communities to reductionist discourse, biologists have popularised the idea of plant blindness to describe an inclination “among humans to neither notice nor value plants in the environment” (Balding and Williams 1192). As a tendency to overlook flora, to underestimate its global ecological significance, or to reduce it to an appropriable resource, plant blindness could reflect the physiological constraints of the human processing of visual information. The pervasiveness of plant blindness and the inability to recognise vegetal lives and their complexities could be one of many factors contributing to the exponential species loss and biocultural disintegration that ever more characterises the Anthropocene.

Ways in which artists have attempted to connect plants and humans once again is through plant poetry and plant literature, a technique and form that incorporates layered, planetary narratives and discourse to not only highlight the wonders of plant life, but to create an interspecies dialogue.

Research into botanical percipience can be traced back at least to Charles Darwin and Jagadish Chandra Bose. Darwin and Bose were the first to imagine and develop novel instruments to make visible the endemic semiosis of vegetal life, or what they came to term plant script. Plant script incorporated modes of interspecies dialogue between humans and plants and made visible the non-linguistic forms of communication of plants, plant-script or plant-autographs. Although forgotten for a long time, this form of collaboration and communication has opened a world of potential for creative arts to engage, evoke and elicit plant sensitivities. Rather than constructing them as objects of representation, it entails the possibility of creative exchange between plants and humans in which plant script intergrades with the production of a text. The potentials of writing practices can therefore initiate new social, biological, political and imaginative perspectives on flora. Human-plant communication can be posited as a basis for interspecies collaboration in which botanical life is an agent, participant within, and contributor to the compositional process.

Rather than passive constituents of the landscape, plants exhibit a range of self-determined behaviours, including learning, remembering, solving problems, making decisions based on prior experiences, interpreting sensory feedback in order to negotiate environments, assimilating information to enhance survival and fitness, and, even, enacting forms of altruism including care.

The plant as co-author has been seen through multiples cases of literature, including eco-fiction, speculative fiction and perhaps most effectively, plant poetry. Examples include Wright’s Five Senses (1963), Murray’s Translations from the Natural World (1992), Easter Sunday (1993) and most recently, Power’s The Overstory (2018).

Plant fiction, plant poetry and the co-authorship between plants and humans is an integral part to our project as rather than speculative reverie, pathetic fallacy or barefaced metaphorisation, plant script becomes available to us through practices of listening to, looking at, feeling, tasting, smelling and walking in plant habitats. The interspecies dialogue requires a deeper understanding between fauna and flora, a reconfiguring of our relations on this planet and to one another and a cognitive shift in perspective towards the planetary.

0 notes

Text

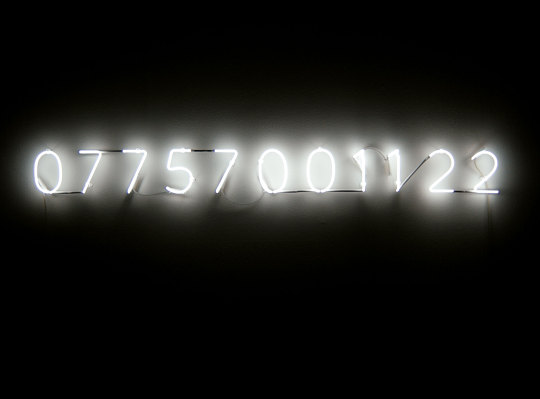

Katie Paterson, Vatnajökull (the sound of)

Katie Paterson’s installation artworks focus on human relationships and connections to both the Earth and the Planetary. She often takes recognisable objects such as pianos, disco balls and, in the case of Vatnajökull (the sound of), a telephone in order to articulate and reflect upon power relations, communications and connections between humans, nature and the planetary.

In Vatnajökull (the sound of) a live phone line was created to an Icelandic glacier, via an underwater microphone submerged in Jökulsárlón lagoon, an outlet of Vatnajökull. The number 07757001122 could be called from any telephone in any country around the world, and the listener would hear the sound of the glacier melting.

The idea was to articulate the devastating effects of the anthropocene and climate change in a more digestible, resonating and human level. So often these issues are seen as too big or too far beyond our reach as a human creating alienation and detachment on our part. Yet by encouraging real-time communication between the humans and nature it created a common language, a common story and a common understanding of how our actions as humans have such tragic implications.

In relation to our exhibition, this work is poignant as it articulates the planetary from an everyday perspective. It encourages the open mindedness, the cognitive shift and the incorporation of multiple perspectives that we attempting as part of our project. Through her multidisciplinary practice, she manages to bring the vast scale and temporal dimensions of geological and cosmological events into sharp focus, creating art that focuses less on the human and more on planetary relationships.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The System of Stability (2016)

Sasha Litvintseva in collaboration with Isabel Mallet

Film / 17 min / 2016

Trailers: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URodDlzjM1Q&t=3s & https://vimeo.com/168080539

By Amy Gowen

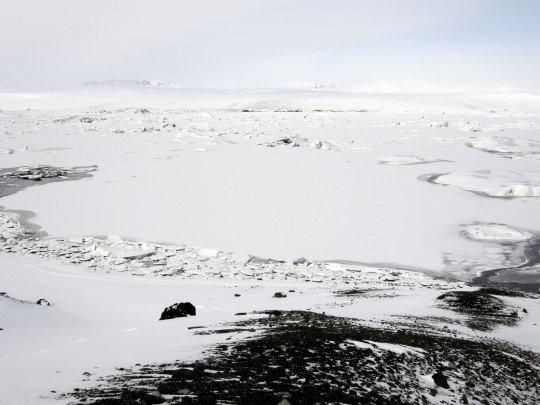

The System of Stability by Sasha Litvintseva, 2016

Artist, researcher, and curator Sasha Litvintseva’s uses film, lecture and text to explore the theory of geological filmmaking. Such filmmaking contemplates the uncertain thresholds of human/nonhuman, inside/outside and visible/invisible through the intersections of media, ecology, history and science in an attempt to challenge typical human-centric narratives. Through geological filmmaking, understood as a form of “experimentation, imaginative invention, and radical thinking,”[1] The System of Stability is key to the aim of this exhibition, to initiate creative, perceptual and philosophical shifts in cognition in order to offer new ways of comprehending ourselves and our relation to the world.

Sasha’s project of Geological Filmmaking includes a larger body of works that each focus on the relationship between humans, non-humans and their direct environments. Through this she engages with the limits of current Anthropocentric narratives by entangling human voice and agency with other geological matter including the likes of volcanic rock faces, desert sinkholes and molecules of poisonous Asbestos in the atmosphere, with a view of engaging with the in/visible power structures at play between humans and non-humans.

The System of Stability by Sasha Litvintseva, 2016

The System of Stability in particular acts as an encounter with the landscape on its own terms, where the inorganic takes the narrative lead, commanding the attention of the viewer. The film is divided into three parts, the opening animation and voiceover is of a mathematical point, a single white dot against a black background. The point narrates itself through a monologue that describes its transition from nothingness to existence, inviting its audience to contemplate the lives of matter we typically assume to have little or no agency. The middle section builds on this notion and is composed of mostly static frames of the rocky terrain of the volcanic island of Lanzarote, accompanied by an intrusive and jarring score that reflects the power and omnipresence of the landscapes on screen. Finally a closing scene of the landscape in motion is accompanied by a new narrator, one that is positioned clearly from a human perspective - we see the landscape from a moving car as the camera “blinks” to mimic human sight. The landscape moves by at increasing speed as the human narration begins to contribute to the loss of subjectivity that the film evokes. After having lived on Earth for millions if not billions of years, the rocks we see on screen help narrate quite different stories about the world than the ones told by human beings, making it clear that it is not the human who exerts the dominant voice within this film, cuing us to consider that the living planet is not only for us.

Litvintseva takes inspiration from critic and filmmaker Jean Epstein who wrote in 1923 that “if we wish to understand how an animal, a plant or a stone can inspire respect, fear and horror - those three most sacred sentiments - I think we must watch them on the screen, living their mysterious, silent lives, alien to the human sensibility.”[2] In The System of Stability the camera eye is in essence non-human, unburdened by the knowledge and meaning of the objects it captures, therefore granting it the ability to represent other nonhuman agencies. Sasha states that through her geological filmmaking she is “trying to visually disrupt the hierarchies governing relations between subject and object, nature and culture – the dichotomies inherited from modernity that have not served us well.”[3] From this her theory of filmmaking can be understood as a visual strategy for the Anthropocene in order to think and feel on geologic scales and time frames that incorporate the other-than-human as much as the human, in doing so The Stability of the System probes into the vibrancy of matter and the creative agency of nonliving things.

The System of Stability by Sasha Litvintseva, 2016

This is a key work within Planetary Awareness for Earthlings in a Post-global Age as Sasha Litvintseva successfully challenges our current unconscious dependence upon globalist, anthropocentric perspectives and frameworks. Described as depicting a “quiet catastrophe,”[4] the film attempts to test preconceived attitudes through the (re)thinking of ideas such as natureculture, non-human agency and deep time to encourage an increased planetary vision of a world which portrays multiple perspectives, as well as illustrating an alternative frameworks that can acknowledge the ecosystem of the living planet. Through such a narrative reframing, we witness the entanglement of human and non-human agencies to produce a more nuanced, emphatic and layered perspective, aiding in our aim to (re)member, (re)shape and (re)join our relationship with the living planet. Moving away from the human-centric and towards the Planetary perspective.

References:

[1] "Sasha Litvintseva Texts." Sasha Litvintseva. Accessed December 21, 2018. https://www.sashalitvintseva.com/gftext.

[2] Transformations Journal – Transformations Journal of Media, Culture & Technology. Accessed December 21, 2018. http://www.transformationsjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Trans30_03_mulvogue.pdf.

[3] "Visual Strategy for the Anthropocene." INRUSSIA. Accessed December 21, 2018. http://inrussia.com/visual-strategy-for-the-anthropocene.

[4] Transformations Journal – Transformations Journal of Media, Culture & Technology. Accessed December 21, 2018. http://www.transformationsjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Trans30_03_mulvogue.pdf.

Further Reading:

http://www.transformationsjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Trans32_7_litvintseva.pdf

http://www.transformationsjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Trans30_03_mulvogue.pdf

http://inrussia.com/visual-strategy-for-the-anthropocene

https://culturetechnologypolitics.files.wordpress.com/2018/03/sonic-acts-essay-compressed.pdf

0 notes

Text

Film as visual storytelling in the Anthropocene

One of the ways to adopt and embody a planetary perspective is to revise the ways in which we disseminate language and stories in order to learn about and understand our living planet. One perhaps less obvious example of this is through visual film narrative. A striking example of this is Russia filmmaker Sasha Litvintseva, who explores the cinematic exploration of time and space in the age of ecological crisis, to propose sensual film narratives with a displaced sense of reality linking with ideas of unlearning conventional perspectives and stories surrounding geological events and leaning towards an a more open planetary perspective. Currently based in London, the artist, researcher, and curator has developed her own cinematic language of “geological filmmaking” by exploring the time outside of the present moment and the body, as well as cinema’s potential ability to participate in processes of geological formation.

She believes that moving image is one of the mediums that can overwhelm the senses making it an appropriate medium with which to create encounters that delve beyond what is perceptually available within human-centrism.

Her projects involve observing and reconceptualizing temporality - filmic and otherwise - materiality of technology as implicated in extraction practices alongside pictorial representations of land and landscape.

Litvintseva states: “Things are not going to stay the same, things are going to deteriorate. We're already seeing it with all kinds of heat records happening way earlier than predicted. But this doesn't mean that it is completely out of our hands and we can just relax and watch it burn. As a cultural producer, I feel a responsibility to try to make work that creates speculative terrains on which to make alternatives for the future imaginable, be they positive or negative.”

Within her films, Litvintseva encourages nature and landscape to lead the narrative, remaining a bystander, steering away from human-led perspectives and uses of the camera in order to embrace multi dimensional planetary narrative.

Click here to watch The Stability of a System a film exploring how subjectivity ends up dissolving into the landscape, into the inorganic, and the question then becomes: What happens to perception and agency with such a dissolution of subjectivity?

To read a the full interview: http://inrussia.com/visual-strategy-for-the-anthropocene

1 note

·

View note