Text

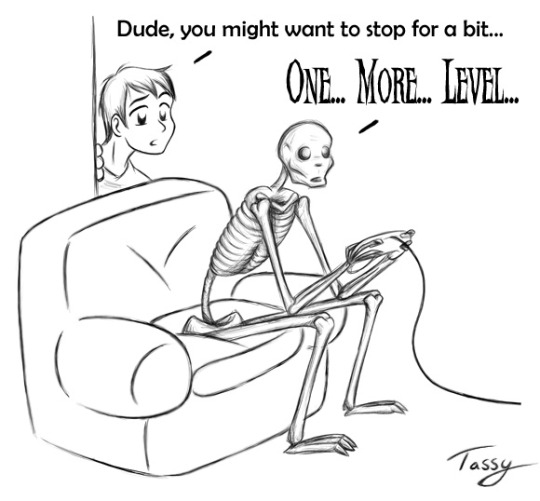

Social Gaming: Playing the Crowd

With an emergence of newer technologies and developments within the gaming world, it is clear that the evolution of gaming is not stopping. Many crucial developments within the industry such as a decline in boxed products (Playstation, Xbox), an increase in online distribution and the use of smartphones for gaming have changed the way in which people interact, communicate and compete whilst playing games (Kowert & Quandt 2017).

Kowert & Quandt (2017) explain that as a social phenomenon, gaming can be regarded as “being coevolving with society and its communication and media technologies”

Over the past ten years, massively multiplayer online role playing games (MMORPGs) have increased in popularity and games such as World of Warcraft have taken online gaming to a new level. In these types of games, players create an alter ego in the form of an avatar to engage in social playing in virtual worlds that also contain thousands of other players (Quandt & Kroger 2013).

These types of games allow users to connect from all over the globe and converse through chat functions of these games working together to reach new levels, combat other teams and so on. Along with this type of success however, has come a concern about the negative consequences of social gaming. Senlow (1984) suggests that video games may impact negatively on an individuals sociability and suggests that electronic friendships (through electronic games) have the ability to replace real world friends. For MMORPG’s in particular, several studies have also indicated that playing these types of games consumes a considerable amount of time (Quandt & Kroger 2013). Yee (2006) found that over 5,000 players per week were spending almost 23 hours online. Advancing and improving an avatar also requires a large amount of time and with these two combined can be a factor in creating a pathological gamer.

Another study by Lemmens, Valkenberg and Peter (2009) revealed that there was positive links between aggression and loneliness, and pathological gaming, whereas life satisfaction and social competence are negatively associated. Despite the fact that gaming online are now highly social spaces, we mustn't forget that it has the potential to disconnect us from one another.

Kowert, R & Quandt, T 2017, ‘New Perspectives on the Social Aspects of Digital Gaming: Multiplayer 2, Taylor and Francis, London.

Lemmens, J, Valkenburg, P & Peter, J 2011 ‘Psychological causes and consequences of pathological gaming’, ‘Computers in human behaviour’, vol. 27, no.1, pp.144-152.

Quandt, T & Kroger, S 2013, ‘Multiplayer: The Social Aspects of Digital Gaming, Taylor and Francis, London.

Senlow, G 1984, ‘Playing Videogames: The electronic friend’, ‘Journal of Communication’, vol. 34, no.2, pp.148-156. Yee, N 2006, ‘The demographics, motivations and derived experiences of users of massively multi-user online graphical environments, ‘Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments’, vol. 15, no.3, pp.309-329.

0 notes

Text

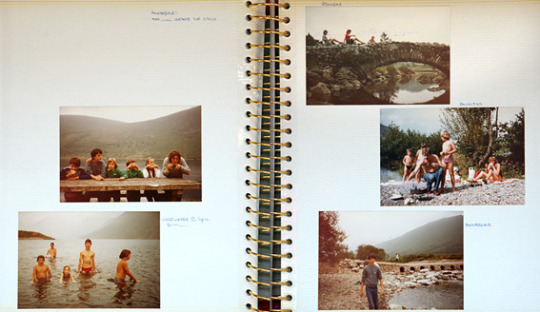

Visual Communities and Social Imaging

As a kid, I have fond memories of sitting on the carpet of our living room flicking through the 20-30 photo albums that my parents had put together. As photography seemed to run through our blood (my grandfather, a professional photographer from Estonia and my father a passionate and talented photographer) I was lucky that so much of my family's history was documented this way. It’s true when they say a picture paints a thousand words and these images helped me to visualise and imagine a time before my own.

Changes in technologies from the first Kodak cameras in the 1800s through to disposables, digital handhelds and now integration into smart phones have produced changes in the way we remember, capture and communicate personal images of family and everyday life (Vivienne & Burgess 2013) Culturally, photography has transformed from a rare and often elitist hobby to an increasingly popular, domesticated and everyday activity (Vivenne & Burgess 2013). Through convergence with social sharing sites such as Flickr, Instagram and Tumblr, the way in which we view, share, promote and understand photography has remediated and transformed entirely. Van Dijck (2008) observed that there was a movement among younger generations to use photography as an instrument for interaction and peer bonding. These days at the touch of a button people can share an image of what they are eating, where they are holidaying, who they are with through apps like Snapchat and Instagram. These images create conversations and communities through the use of hashtags, photo stories and more. No longer is there an 8 hour wait in the dark room for film to develop, users can even upload ‘live’ videos and broadcast this to followers and friends.

Van House (2011) explains that there are four social uses for photography that extend beyond the traditional view of personal and group memory. These include ‘relationship creating and maintenance, self-representation and self-expression.’ Photography combined with social media is not merely to create archives and albums for the family history, but a way in which people can express themselves and their identity.

I will always cherish our family photo albums and am grateful that I was brought up around cameras. Although I am a user of sites such as Instagram and Snapchat and enjoy the ease of sharing and social benefits, there will be nothing better than sitting around with my Dad laughing at old photos and the stories that came with them.

Van Dijck, J 2008, ‘Digital photography: Communication, identity, memory’, ‘Visual Communication’ vol.7, no.1, pp.57–76. Van House, N 2011 ‘Personal photography, digital technologies and the uses of the visual. Visual Studies’. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1472586X.2011.571888 (accessed 31 January 2018).

Vivienne, S & Burgess, J 2013, ‘The Remediation of the Personal Photograph’, Journal of Material Culture, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 279-98.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crowdsourcing in times of crisis

Following an unexpected disastrous event, crisis-affected communities can now stay connected due to the advancements in technology and social networking online. To stay connected with with family, friends and the government, people are now texting, calling and using social media to communicate in times of crisis to provide help and aid worldwide. This process is referred to as crowdsourcing and is defined by Castillo (2016) as: ”an organisational framework that corresponds to processes for procuring services from a large amount of people external to an organisation. For example, from volunteers who are not affiliated with a formal agency in charge of relief efforts” Castillo (2016) explains that social media information is often irreplaceable after a disaster, not only assisting immediately after, but also during the entire life cycle. This includes co-ordinating donations and volunteers, or spreading the word of safety from authorities.

In 2007, the results of Kenya’s presidential election caused uproar and upheaval within the country. Opponent Ralia Odinga refused to accept his defeat leading to riots and extreme violence across Kenya. Any information regarding the killings were suppressed by mainstream media, so a group of Kenyans created a website platform called Ushahidi. The platform allowed activists or anyone with access to the internet or a phone to report when and where attacks were taking place. These attacks or any useful information were placed on a Google map to create simple visual representation (Ushahidi 2014). This process of crowd mapping has allowed the quick exchange of information throughout a number of disasters since with platforms such as Sinsai established by the Japanese after earthquake and tsunami crises and the Christchurch Recovery Map in New Zealand following the earthquake in 2011 (Munro 2013).

Another example of crowd mapping and crowdsourcing in a time of crisis was during the 2010 Haiti earthquake. The nation was able to remain connected as most cell-towers were still working, therefore allowing people to somewhat communicate updates of the changing situation and of people requiring medical attention. Mission 4636 was set up, allowing anyone in Haiti to send a free text message to this number which were translated and mapped via online crowdsourcing platforms (Munro 2013). Over 80,000 messages were processed with a turn-around time of less than 5 minutes from receiving, translation and streamed back to the map (Munro 2013).

Whether it’s marking yourself as ‘safe’ on Facebook or taking a helpful picture and sending it to one of these platforms, there is no doubt that crowdsourcing is an example of the positives that social media and technologies have on crisis events.

Castillo, C 2016, ‘Big Crisis Data: Social media in disasters and time critical situations,’ Cambridge University Press. London. Munro, R 2013, ‘Crowdsourcing and the crisis-affected community: Lessons learned and looking forward from Mission 4636’, Informational Retrieval, vol. 16, no. 2, pp.210-266.

Ushahidi 2014, viewed 3 August 2016, <http://www.ushahidi.com/>

0 notes

Text

Leaving Traces: Trolling and social media conflict

Although I don’t have kids of my own yet, I couldn’t bear to think of my child coming home in tears from school at the hands of a bully. In my mind, when I think of the word bully, I think of a big ogre-like kid who is always older (and most of the time less intelligent) staring down at the younger kid/s trying to assert some sort of power or authority. Usually he (or she) is name calling, teasing or making fun of someone else. Whether I have developed this image through various movies and teenage television shows I just can’t help but to think of this type of scenario. Perhaps it’s movies like Mean Girls, where a bunch of stuck up popular high school girls poke fun at other kids because they aren’t ‘cool’ enough, or dress differently. This is how I imagine and first handily remember bullying at school, but for kids these days the emergence of social networking and social media sites means bullying can take place not only in the school grounds, but at home as well from behind a screen. It’s a little more complicated than I first thought and had me wondering is social media making bullying worse?

A Swedish psychologist by the name of Dan Olewus, explains that the act of bullying involves 3 components which are: aggression, repetition and an imbalance in power (Boyd 2014) His definition suggests that bullying involves someone of a differential social or physical power subjecting another to repeated and frequent physical, social and psychological aggression which matches my initial though of a bully (Boyd 2014). Social media sites such as Facebook however, break down barriers such as physical aggression for example allowing anyone with an internet connection to facelessly cyber bully others from the comfort of their home.

Boyd (2014) explains that the visibility of bullying on social media and networked publics adds a new depth as to how bullying is understood and constructed. But is it getting more complex because it’s right there in our face? Even though a victim may not want to talk about it, it’s there for everyone to see. Boyd (2014) also argues that the traditional view of the perpetrator and the victim fails to understand the complexity of online conflicts. Anything posted on a public forum leaves traces enabling more and more people to witness these acts of bullying. At the same time, these forums create opportunities for others to intervene (Boyd 2014).

Sites such as Facebook and YouTube play significant roles in creating spaces for ongoing interaction and creating content communities, however the visibility of these conversations can cause emotional stress to the victim of bullying (McCosker 2013).

Boyd, D 2014, ‘Bullying: is social media amplifying meanness and cruelty?’, ‘It’s Complicated: the social lives of networked teens’, Yale University Press, USA pp. 128-152. McCosker, A 2013, ‘Trolling as Provocation: YouTube’s agonistic publics’, ‘Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies’, vol. 20, no. 2.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Activism and Protest

The beauty of social networking, is that it provides a space, an arena to communicate and in the way of political and social movements, it allows individuals to easily share their support or stance on issues that can facilitate public protests. On platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, users have an opportunity to be seen by friends and family and promote themselves and their identity. If Julie ‘likes’ Yoga for Life’, ‘Meditation Australia’ and ‘Whole Foods Recipe’ pages on Facebook is she perceived as being someone who is health conscious, spiritual and an overall good human being? The same goes for someone who changes their Facebook profile picture with a French flag overlay suggesting support for a country after a devastating and fatal occurrence. Are they perceived as being compassionate and caring for the disaster? Or is this just a way to prove to others (or even yourself) that you are making a difference to a social cause?

A question often raised as to whether communicating satisfaction or dissatisfaction with social or political causes using platforms like Twitter and Facebook has the same meaning as getting out in the streets protesting or lobbying does (Frame & Brachotte 2016). Does a simple ‘like’ or ‘follow’ on Facebook really make a change or is this action simply meaningless and a time saving, effortless way to show that you somewhat care?

Morozov (2009) debates that clicktivism or similarly slacktivism is the ideal type of activism for a lazy generation and makes online activists feel important and useful while having little to no political impact. A definition by Oxford Dictionary (2018) states that clicktivism is “the practice of supporting a political or social cause via the internet by means such as social media or online petitions, typically characterised as involving little effort or commitment.”

An example of clicktivism in 2012 was the Kony campaign launched by group Invisible Children, which aimed to raise awareness of the horrific and numerous crimes committed by Joseph Kony. The campaign aimed to make him the most infamous person in the world, therefore leading to his ultimate capture. The result, a 30 minute film with graphic imagery which broke viewing records across the globe. The video encouraged people to sign pledges, spread the word and buy a whole lot of Kony merchandise. The success of the campaign was huge, with millions of dollars raised and the video viewed and shared immensly, however after all of this, Kony was never captured and still remains at large. As one of the most popular forms of political participation in the world (Halupka 2018) clicktivism will always be present but to what degree are these actions making any change?

Frame, A & Brachotte, G 2016, Citizen Participation and Political Communication in a Digital World, Routledge Studies in New Media and Cyberculture, Taylor & Francis, New York.

Halupka, M 2018 ‘The Legitimisation of Clicktivism’, Australian Journal of Political Science, vol.53, no.1, pp. 130-141.

Mozorov, E 2009, ‘The Brave New World of Slacktivism’, Foreign Policy, 19 May 2009, viewed 27 January 2018, < http://foreignpolicy.com/2009/05/19/the-brave-new-world-of-slacktivism/>. Oxford Dictionary 2018, Definition of Clicktivism, Oxford Dictionary Online, viewed 27 January 2018, <https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/clicktivism>

1 note

·

View note

Text

Politics and Civic Cultures

In the lead up to election time, it’s pretty hard to avoid those persuasive and aggressive political ads that seem to pop up right in the middle of your favourite new cooking show. Footage of politicians visiting schools, kissing babies in hospitals (okay that might be too cliché) and everything else seem to be in your face all the time. As a politician, one must relate to a broad spectrum of citizens, who in many circumstances show low trust in them, weak or no interest in politics and low levels of electoral participation (Manning et. al 2017). This disengagement with politicians is prominent for young people and politicians are increasingly trying new ways to gauge and rally support from the Gen Y’s.

Politicians these days repeatedly try to present themselves as authentic and relatable people in order to connect with voters (Manning et. al 2017). In a recent biography of the former British prime minister titled: David Cameron: Call Me Dave, the former leader portrays feelings of casualness and informality in an effort to cultivate a less formal and relatable image of himself, detailing private details about his home and family life. (Ashcroft and Oakshott 2015). The sharing of private life and even humility has become a way of gaining legitimacy for politicians and bridging the divide (Manning et. al 2007). Take Kevin Rudd for example; his social media presence around the 2013 election was a lot more down to earth and open compared to Tony Abbott. An approach fostering self-ridicule and humour left Australians feeling like he was ‘one of them’ in particular posting a selfie on Instagram of himself cutting his face whilst shaving.

Social media has the power to facilitate exchange, accountability and promote political engagement for people (not just young) but also for those who don’t understand politics entirely and could feel excluded from this type of conversation (Keane 2002). If Kevin Rudd cut his face shaving then that doesn’t make him perfect right? He’s just a normal guy, trying to do normal things and through posts like this can reach an audience who he may never have related to before.

In a study by Manning et. al 2017 findings revealed that young people desire a more genuine and accessible voice from politicians, but still held the view that politicians needed to be professional and worthy of respect. So is there a risk of being too intimate and over sharing on social media? How much is too much and what is acceptable conduct for politicians on social media? Was posting a picture of a shaving mishap maybe too much to see and entirely irrelevant to the big issues in politics? These questions pose a difficult scenario to politicians and make it hard to find the right balance as they may seem out of touch with the youth of today if they aren’t using social media platforms. Decreasing participation in this age group means that the role of social media has become more important than ever.

Ashcroft, M and Oakeshott, I 2015, ‘Call me Dave: The Unauthorised Biography of David Cameron, London, Biteback Publications.

Keane, J 2002 ‘Whatever Happened to Democracy’, Institute for Public Policy Research, London IPPR Manning, N, Penfold-Mounce, R, Loader, B Vromen, A & Xenos, M 2017 ‘Politicians, Celebrities and Social Media: A case of informalisation?’ Journal of Youth Studies, vol.20, no. 2, pp.127-144.

0 notes

Text

Great blog post Amanda! I found the below interesting from your post: “Up to 34% of employers said they did not hire a candidate after scanning them on social media (Forbes, 2017) and numerous people have been fired after comments they made on social networking sites (Price, 2016)” This has become a heated debate over the past few years, with privacy becoming a concern. Businesses now need to ensure that they have put together social media policies with legal teams to ensure that employees know what they can and can’t post about their organisation in a public forum or on their personal social media page and what is deemed appropriate/inappropriate.

Digital Communities

Prior to social media, people primarily congregated together via proximity within their home town and managed their image via their dress, language, choice of career, social circles, family stature and hobbies (Wilken & McCosker, 2014). There was no manner in which to erase something that occurred in real time and socialising generally occurred face to face.

People crave empathy from others yet friendships are often disappointing (Turkle, 2013). Following the invention of the internet in the 1990’s, digital technology allowed a new form of socialising to unravel that connected people far beyond proximity. Social media is an electronic tool that allows the public to distribute and access information, chat online and develop relationships. Social networking platforms allow the public to maintain a public or partially public profile whilst connecting with other users (Murthy, 2013).

YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and other platforms allow people to participate in a type of online democracy, connected by their beliefs, values, interests and sub-cultures with no formalised leader (Siapera, 2012). They provide companionship without the negative aspects of friendship and allow people to manage their own perceived image online (Turkle, 2013).

Personalisation, customisation and portability of membership creates networked individualism for users (Siapera, 2012). One can log on 24/7 to the same place from any location, reveal as much or as little as they wish to and operate within any groups of interest they want to (Siapera, 2012). Unexpected benefits were seen when a man with HIV was able to blog about the details of his illness which allowed his friends and others to properly understand HIV, in turn decreasing social awkwardness and stigmas about his medical condition (Boyd, 2012).

With these benefits comes a number of disadvantages. For example, digital communities can facilitate conversation that leads people to polarised groups of like-minded people who then miss out on hearing diverse and contradictory ideas (Gillespie, 2010). Platforms often don’t allow people to represent themselves across different parts of their lives, such as professionally and socially (Siapera, 2012). Up to 34% of employers said they did not hire a candidate after scanning them on social media (Forbes, 2017) and numerous people have been fired after comments they made on social networking sites (Price, 2016). There is also privacy to consider when personal details are volunteered by users, or expected as part of membership terms (Gillespie, 2010). It is difficult to estimate the negative impact social media has on society. For example, knowing people in one’s local community can lower the crime rate (Putnam, 2012) and yet this form of neighbourly friendship has dropped dramatically since social media’s inception. Digital communities have ultimately added a layer to the presence and accessibility people offer the world resulting in positive and negative impacts that are still unfolding (Wilken & McCosker, 2014).

References

Boyd, D 2012, ‘Participating in the always-on lifestyle’, in M Mandiberg (ed) The Social Media Reader, NYU Press, pp. 71-76.

Forbes, 2013, ‘How social media can help or hurt your job search’, viewed 13 November 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jacquelynsmith/2013/04/16/how-social-media-can-help-or-hurt-your-job-search/#1c5ce6ce7ae2.

Gillespie, T 2010, 'The politics of platforms’, New Media & Society, vol. 12, no. 3, Sage.

Price, L 2016, ’20 tales of employees who were fired because of social media posts’, viewed 16 November 2017, http://people.com/celebrity/employees-who-were-fired-because-of-social-media-posts.

Putnam, R 2012, Robert Putnam - Bowling Alone, 19 December, viewed 13 November 2017, <http://www.c-span.org/video/?c4236758/robert-putnam-bowling-alone>.

Siapera, E 2012, ‘Socialities and Social Media’, in Understanding New Media, Sage, London, pp. 191-208.

TED-Ed 2013, Connected, but alone?- Sherry Turkle, 19 April, viewed 9 November 2016, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rv0g8TsnA6c>.

Wilken, R & McCosker, A 2014, 'Social Selves’, in Cunningham & Turnbull (eds), The Media & Communications in Australia, Allen and Unwin pp. 291-295.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A new kind of community

Would you be more likely to share something when you knew it was going to be well received by others? Or share a story/experience with others that you knew had gone through the same thing and could relate to you? Imagine your local community: aged young and old, with different beliefs, different religions, different interests and different hobbies. A community that is grouped by location and where they choose to reside for example. Would you feel more comfortable speaking publically to them about a topic close to your heart? Or have fear of being judged, or excluded from this group of people. Public speaking is a daunting task for most, or even sharing a sensitive topic for that matter.

What if there was a way you could relate to others in the same boat as you? Social media platforms now facilitate the sharing of information between people and the co-creation of knowledge that is shaped by personal experience (Sosnowy 2014). These platforms encourage virtual communities; spaces where shared social practices and interests are sustained and mediated by electronic communication (Siapera 2012). These communities come together on the basis of sharing feelings, desires, ideas and information without any face to face contact between them and exist independent of geographical location (Siapera 2012).

Boyd (2012) explains that many people who take to these virtual communities, are not writing and sharing for the world at large, but writing and sharing for a small group who may find their information meaningful and relevant to them. This can be demonstrated through the art of blogging, and in particular illness blogging. These type of discussion forums, help sufferers gain an understanding of their situation and share with others who are trying to apprehend how to cope with new found illness. Through blogging, individuals feel liberated and empowered through the act of story-telling and self expression and enable patient led discourse communities (McCosker 2008). Research shows that finding out other people are facing similar difficulties may help one to feel more confident and normal is managing health conditions in contexts such as work, family, travel and relationships (Ziebland 2012).

Jessica Oldywn’s personal illness blog: ‘Toom-ah? What Stinkin’ Toom-ah!’ is a brave look into the life of someone diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. Her blog discusses her journey and quest for healing and believes that by sharing her story, she will inspire and motivate others to know they aren’t going through this alone. Her blogging is raw, however her positivity and is both engaging and infectious.

You can find the blog here: https://jessicaoldwyn.blogspot.com.au

References:

Boyd, D 2012, ‘Participating in the always-on lifestyle’, in M Mandiberg (ed) The Social Media Reader, NYU Press, pp. 71-76

McCosker, A 2008, ‘Blogging Illness: Recovering in Public’ Journal of Media and Culture, vol. 11, no. 6

Siapera, E 2012, ‘Socialities and Social Media’, in Understanding New Media, Sage, London

Sosnowy, C 2014 ‘Practicing Patienthood Online: Social Media, Chronic Illness and Lay Expertise, MPDI Journal of Societies, vol 4, no. 1, pp.316-329

Ziebland, S 2012 ‘Health and Illness in a Connected World: How Might Sharing Experiences on the Internet Affect People’s Health?’A Multidisipliary Journal of Population Health and Health Policy, vol 90, no. 2, pp.219-249.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How much is too much?

About a week ago, a friend of mine mentioned that one of her work colleagues was spending just under 2 hours of her week scrolling through her Instagram feed. Surprised and quite perplexed, she explained how she couldn’t understand how someone could spend so much time on social media over a week. “But how did she get that final number?” I thought. Oblivious and obviously not overly tech-savvy, my friend began to explain to me that in the iPhone settings, you can see which Apps your battery is using the most in the last 24 hours and also over the past 7 days. After saying our good-byes I couldn’t help but wonder and question how many hours out of my week was being taken up by mindlessly double-tapping, liking and tagging my friends in funny memes. I jumped on straight away, and I’m glad I didn’t in front of my judgemental friend. 2.9 hours! How could this be? Sure a scroll here and there, a scroll before I hit the pillow, another scroll sitting on the tram passing time. I started to question whether or not this in fact was too much time and if I was starting to have an unhealthy addiction.

Boyd (2012) outlines that to an outsider, wanting to be ‘always-on’ is all too often labelled as an addiction and may seem even pathological. It is assumed, that it is the technology we are addicted to, but on the contrary humans want to interact, connect with others, and are always curious. They take advantage of the affordances that these social media platforms (such as Instagram) provide to their sense of being part of a community, belonging and feeling connected (Boyd 2102).

An Australian documentary by Eva Orner called “It’s people like us” was released in September this year, to expose the dependence Australians have on smartphones and questions how they have developed into an extension of ourselves. The documentary follows five young Australians who agree to be filmed over a week period whilst driving, and the results are more than alarming. Each participant is filmed being drawn to their screens, staring down at their phones with several near-misses caught on tape. Taking selfies, sending snapchats, checking Facebook are all activities these participants were guilty of whilst driving. Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xnJqHhkvtNs Orner (2017) explains that the film aims to start a community conversation about using mobile phones at inappropriate times, and argues that it is people like us who are doing it, and people like us who can also decide that it’s not okay. Although the concept of being ‘always on’ has many benefits such as connectedness and a sense of belonging, it is key to find a balance between when and how we should use social media and how it is going to affect others. References: Boyd, D 2012, ‘Participating in the always-on lifestyle’, in M Mandiberg (ed) The Social Media Reader, NYU Press, pp. 71-76 Kuss, D 2017 ‘Social Networking Sites and Addiction: Ten Lessons Learned’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 14, no.3, pp.311 Omer, E 2017, It’s People Like Us Documentary, Positive Ape, viewed 1 December 2017, < http://www.itspeoplelikeus.com.au>.

11 notes

·

View notes