Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Gather Around the Campfire

As long as we have had humans we have had stories. Over the millennia, groups would gather around the fire, exchanging everything about their lives from their harrowing pursuits to gossip about who is marrying who in the neighboring clan. It's well documented that stories have a unique pension to move and compel individuals. Our fascination with stories is a borderline inexplicable law of nature. It only follows that a phenomena so powerful could also be employed to shape consumer preferences and nudge individuals to desired behavior.

As I reflect on how stories impact my current project, changing the perception of the Sloan Fitness Industry club from a workout group to a professional organization, I see an opportunity to apply narrative as a tool in my arsenal. Though the organization is relatively new, it may be helpful to present success stories to "customers" (students in this case) at points along their journey. These stories may correspond to using the club to find jobs or contacts in the fitness industry, or in relation to finding purpose/direction in their careers through the organization. Once crafted, we can use these stories during the first club event of the year next semester, as well as on sloangroups and other touchpoint with students. We could also make these stories a part of our social media campaign.

0 notes

Text

An age old problem

In Gourville's HBR article "Four Products: Predicting Diffusion", he mentions the challenge in predicting adoption of new products as they come to market. Even if the market is accurately sized, the rate of adoption, or diffusion, can vary substantially based on a variety of factors. Gourville presents four vastly different products in various stages of development as an example. These include sliced peanut butter (akin to Kraft sliced cheese), Turf for horses, a foldable bicycle wheel, and unique high end custom puzzles.

In regards to the speed of adoption (and not conflating with overall market penetration), I believe that the products that will diffuse in the following order (fastest to slowest)

Horse Turf

Puzzle

Peanut butter

Folding bicycle wheel

While it is surprisingly easy to rank the perceived viability of each of these products, it is more difficult to rationalize what criteria influence these rankings. Broadly, I've broken them up into the following

Is there a clear need or want for the product by a certain demographic?

In the case of the horse turf, there was a clear need to decrease the impact on horses and trackable impact of the product. For the puzzle, there was a clear want aroused in certain customers, for this niche and expensive product (to those that the product appeals to, it really appeals). In the case of peanut butter, the need was not clearly articulated, and the problem solved is quite trivial. In fact, most individuals would choose to not purchase pre sliced peanut butter at a premium if given the choice.

Are network effects present?

The effect of goodwill and word of mouth cannot be understated in predicting the diffusion of a certain product. If that product can generate buzz and net positive excitement once it is released, the amount of consumers will continue to multiply. This is clearly the case with the horse turf, but certainly not with the folding bicycle wheel for example where the goal of the creator was to sell to any bicycle maker that would want it.

In summary, predicting the demand of a new product is challenging, and will often be done incorrectly. If it is possible to collect information through experimentation and release/manufacture in cycles, that is probably the best bet in a product launch. Additionally, creating production cycles will introduce scarcity, potentially further increasing the value of a new product to a brand.

0 notes

Text

The Hidden Costs of Frictionless Experiences: A Call for More Good Friction in Subscription Models

Subscription services are deeply woven into the fabric of our digital lives, from streaming platforms to software suites. But beneath the surface convenience of these services lies a troubling reliance on dark patterns—design tactics that manipulate users into making decisions against their best interest. Two prevalent examples deserve our scrutiny:

Hiding the Unsubscribe Options: Many services bury the option to cancel subscriptions in layers of menus or obscure it in fine print, making it frustratingly difficult for users to find and exercise their choice to stop the service.

Manipulative Free Trials: By requiring payment information upfront and making the cancellation process cumbersome, companies ensure that many users end up paying for at least a month or more of service unintentionally. Worse still, if a user cancels a free trial, access is often cut immediately, rather than at the end of the trial period, dissuading cancellations and encouraging passive subscription renewals.

These tactics exemplify what professor Gosline refers to in her article as bad friction—obstacles that reduce consumer autonomy and exploit cognitive biases for corporate gain. In stark contrast, Gosline champions the concept of good friction: deliberate touchpoints in the customer journey that enhance transparency, ethical practices, and ultimately, customer empowerment.

In fact, there is a whole industry now designed around helping individuals avoid unwanted subscriptions (E.g., Rocketmoney).

Imagine a subscription model where companies:

Alert Users at the End of a Free Trial: A simple notification asking if the user wishes to continue with the service can build trust and respect for consumer autonomy.

Simplify the Unsubscription Process: Making it as easy to unsubscribe as it is to subscribe respects the user’s choice and fosters a healthier long-term relationship.

Incorporating these elements of good friction can transform customer experiences from being manipulative to being genuinely supportive. Companies need to prioritize long-term trust over short-term gains. By doing so, they not only adhere to ethical standards but also foster real loyalty and satisfaction among their users.

Let's advocate for more responsible business practices that respect user agency and encourage true engagement. It's time to shift the paradigm from exploiting frictionless experiences to enhancing them with meaningful interactions that put human needs first.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Customer Journeys

In analyzing how customer journeys can impact the user experience, let's consider two customer experience processes with similar goals, and the effects each of these journeys have on the consumer. I'll draw from my personal experience over the last few months and place a particular emphasis on the following:

Actions: What is the customer doing at each stage? What actions are they taking to move themselves on to the next stage?

Motivations: Why is the customer motivated to keep going to the next stage? What emotions are they feeling? Why do they care?

Questions: What are the uncertainties, jargon, or other issues preventing the customer from moving to the next stage?

Long story short, I recently took an American Airlines flight for my recent trip to Colombia which I booked on my American Express card. My flight was delayed nine hours, cancelled, and rebooked for a day later. We were provided no information, no compensation or accommodation, and the company also lost our bags during this endeavor. I had a similar goal to achieve through both companies - AMEX and American Airlines, but my experience in working with the firms differed dramatically.

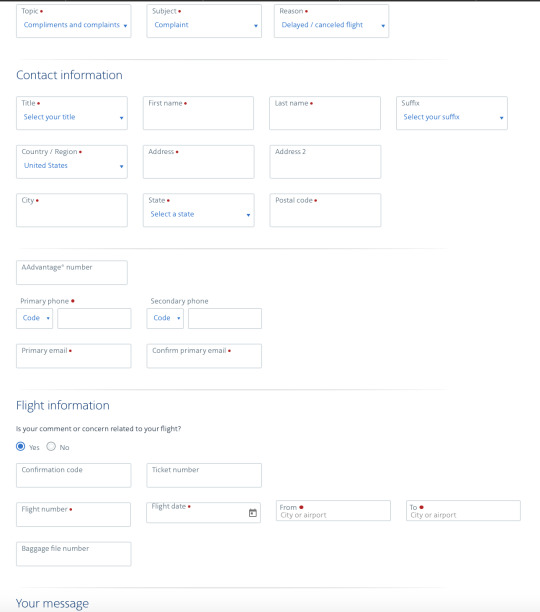

With American Airlines, it was unclear which medium I should use to seek help - I waited in line at the airport customer desk for several hours before being directed to call the support team on my phone. After a four hour wait on the phone and an absurdly long robot menu, my representative told me to file a report on the website, without providing any support on how to do so. Arriving at the website, I find a myriad of data (much of which is superfluous for the airline, who needs little more than my last name to track down my flight)

It's unclear at every stage which actions I should be taking to move forward, and it feels that every stage is designed to reduce my motivation to continue along the process to receive help. If anything, I am left with further questions at each stage of the process than beforehand.

Contrast this with American Express who has a very clear customer journey - call the number on your card (there's no email provided, and all resources ask you to call directly). Once you call you will be put in touch with a representative immediately that listens to your problem, and even if they can't help you, they will prescribe the specific next actions, and then immediately transfer you on the phone then and there to the relevant department (insurance in my case) and provide an account of your previous call to expedite the resolution process. The insurance agent even filled out the first few steps of the claim for me before sending my a form to complete myself.

Though the outcome was similar in both cases, filling out a complaint/claim form, one journey left me satisfied and vindicated, while the other radicalized me into a violent campaign to take down the organization. Simple changes in the customer process to clarify what actions are needed to move to the next stage, acknowledge the customers feelings at each stage, and preemptively answer questions or provide a forum to answer questions can have a compounding effect on the customer journey.

2 notes

·

View notes