Text

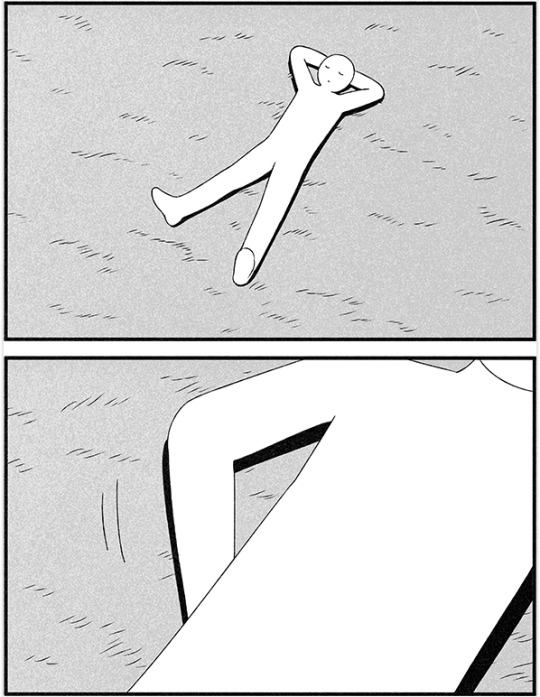

Nada más que esperar; eterno desamparo.

Franz Kafka, Diarios (1910-1923).

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

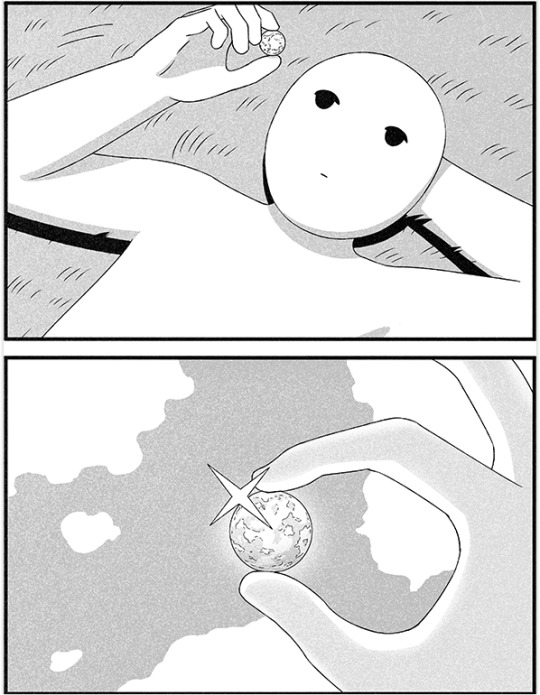

Jorge Luis Borges. Final de año. Fervor de Buenos Aires. [01]

63 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Le rogó a Dios que le concediera al menos un instante para que él no se fuera sin saber cuánto lo había querido por encima de las dudas de ambos, y sintió un apremio irresistible de empezar la vida con él otra vez desde el principio para decirse todo lo que se les quedó sin decir, y volver a hacer bien cualquier cosa que hubieran hecho mal en el pasado.

Gabriel García Márquez. El amor en los tiempos del cólera. (via eljujeniodeletras-world)

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aire

Hablando del aire.

Si algún enclenque espíritu quisiera referirse a tal cuerpo inmaterial que abraza las bóvedas, desparasita las cristaleras y despluma el verano en suelos bañados de otoño como ciencia infusa, hubiera de saber que su escepticismo no es más que la sombra de alguien que crecerá en cuerpo pero no así en experiencia, tampoco en sabiduría.

Si osara continuar en tratar de desvelar con palabras lo que la vista nunca arriba, ha de saber que la intuición no está en el tacto ni la fe casi dogmática en un suceso es palpable, pues hay enfermos de amor sublevados con el aire, hay pozos de melancolía donde, cansados, saltan miles de cientos de náufragos a sumirse en las fauces de los rincones vacíos, donde pasa todo y nada pasa, donde muere un cuerpo y se disipa un alma.

No he venido a escuchar mentiras, ni a ser adulado por farsantes, ni a ser seducido por medias verdades de palabras ya antes mordidas, que la vanidad es una luz maleable de la que crecen flores, pero también enanos,

que yo he venido aquí a morir para que el alma no duela, que la voz de la tierra es dulce como la lluvia pausada del mes de mayo.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The sun will rise in the morning. I’m going to have a drink at six. That’s my faith.

58 notes

·

View notes

Link

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is God a Taoist?

Mortal:

And therefore, O God, I pray thee, if thou hast one ounce of mercy for this thy suffering creature, absolve me of having to have free will!

God: You reject the greatest gift I have given thee?

Mortal: How can you call that which was forced on me a gift? I have free will, but not of my own choice. I have never freely chosen to have free will. I have to have free will, whether I like it or not!

God: Why would you wish not to have free will?

Mortal: Because free will means moral responsibility, and moral responsibility is more than I can bear!

God: Why do you find moral responsibility so unbearable?

Mortal: Why? I honestly can't analyze why; all I know is that I do.

God: All right, in that case suppose I absolve you from all moral responsibility but leave you still with free will. Will this be satisfactory?

Mortal (after a pause): No, I am afraid not.

God: Ah, just as I thought! So moral responsibility is not the only aspect of free will to which you object. What else about free will is bothering you?

Mortal: With free will I am capable of sinning, and I don't want to sin!

God: If you don't want to sin, then why do you?

Mortal: Good God! I don't know why I sin, I just do! Evil temptations come along, and try as I can, I cannot resist them.

God: If it is really true that you cannot resist them, then you are not sinning of your own free will and hence (at least according to me) not sinning at all.

Mortal: No, no! I keep feeling that if only I tried harder I could avoid sinning. I understand that the will is infinite. If one wholeheartedly wills not to sin, then one won't.

God: Well now, you should know. Do you try as hard as you can to avoid sinning or don't you?

Mortal: I honestly don't know! At the time, I feel I am trying as hard as I can, but in retrospect, I am worried that maybe I didn't!

God: So in other words, you don't really know whether or not you have been sinning. So the possibility is open that you haven't been sinning at all!

Mortal: Of course this possibility is open, but maybe I have been sinning, and this thought is what so frightens me!

God: Why does the thought of your sinning frighten you?

Mortal: I don't know why! For one thing, you do have a reputation for meting out rather gruesome punishments in the afterlife!

God: Oh, that's what's bothering you! Why didn't you say so in the first place instead of all this peripheral talk about free will and responsibility? Why didn't you simply request me not to punish you for any of your sins?

Mortal: I think I am realistic enough to know that you would hardly grant such a request!

God: You don't say! You have a realistic knowledge of what requests I will grant, eh? Well, I'll tell you what I'm going to do! I will grant you a very, very special dispensation to sin as much as you like, and I give you my divine word of honor that I will never punish you for it in the least. Agreed?

Mortal (in great terror): No, no, don't do that!

God: Why not? Don't you trust my divine word?

Mortal: Of course I do! But don't you see, I don't want to sin! I have an utter abhorrence of sinning, quite apart from any punishments it may entail.

God: In that case, I'll go you one better. I'll remove your abhorrence of sinning. Here is a magic pill! Just swallow it, and you will lose all abhorrence of sinning. You will joyfully and merrily sin away, you will have no regrets, no abhorrence and I still promise you will never be punished by me, or yourself, or by any source whatever. You will be blissful for all eternity. So here is the pill!

Mortal: No, no!

God: Are you not being irrational? I am even removing your abhorrence of sin, which is your last obstacle.

Mortal: I still won't take it!

God: Why not?

Mortal: I believe that the pill will indeed remove my future abhorrence for sin, but my present abhorrence is enough to prevent me from being willing to take it.

God: I command you to take it!

Mortal: I refuse!

God: What, you refuse of your own free will?

Mortal: Yes!

God: So it seems that your free will comes in pretty handy, doesn't it?

Mortal: I don't understand!

God: Are you not glad now that you have the free will to refuse such a ghastly offer? How would you like it if I forced you to take this pill, whether you wanted it or not?

Mortal: No, no! Please don't!

God: Of course I won't; I'm just trying to illustrate a point. All right, let me put it this way. Instead of forcing you to take the pill, suppose I grant your original prayer of removing your free will -- but with the understanding that the moment you are no longer free, then you will take the pill.

Mortal: Once my will is gone, how could I possibly choose to take the pill?

God: I did not say you would choose it; I merely said you would take it. You would act, let us say, according to purely deterministic laws which are such that you would as a matter of fact take it.

Mortal: I still refuse.

God: So you refuse my offer to remove your free will. This is rather different from your original prayer, isn't it?

Mortal: Now I see what you are up to. Your argument is ingenious, but I'm not sure it is really correct. There are some points we will have to go over again.

God: Certainly.

Mortal: There are two things you said which seem contradictory to me. First you said that one cannot sin unless one does so of one's own free will. But then you said you would give me a pill which would deprive me of my own free will, and then I could sin as much as I liked. But if I no longer had free will, then, according to your first statement, how could I be capable of sinning?

God: You are confusing two separate parts of our conversation. I never said the pill would deprive you of your free will, but only that it would remove your abhorrence of sinning.

Mortal: I'm afraid I'm a bit confused.

God: All right, then let us make a fresh start. Suppose I agree to remove your free will, but with the understanding that you will then commit an enormous number of acts which you now regard as sinful. Technically speaking, you will not then be sinning since you will not be doing these acts of your own free will. And these acts will carry no moral responsibility, nor moral culpability, nor any punishment whatsoever. Nevertheless, these acts will all be of the type which you presently regard as sinful; they will all have this quality which you presently feel as abhorrent, but your abhorrence will disappear; so you will not then feel abhorrence toward the acts.

Mortal: No, but I have present abhorrence toward the acts, and this present abhorrence is sufficient to prevent me from accepting your proposal.

God: Hm! So let me get this absolutely straight. I take it you no longer wish me to remove your free will.

Mortal (reluctantly): No, I guess not.

God: All right, I agree not to. But I am still not exactly clear as to why you now no longer wish to be rid of your free will. Please tell me again.

Mortal: Because, as you have told me, without free will I would sin even more than I do now.

God: But I have already told you that without free will you cannot sin.

Mortal: But if I choose now to be rid of free will, then all my subsequent evil actions will be sins, not of the future, but of the present moment in which I choose not to have free will.

God: Sounds like you are pretty badly trapped, doesn't it?

Mortal: Of course I am trapped! You have placed me in a hideous double bind! Now whatever I do is wrong. If I retain free will, I will continue to sin, and if I abandon free will (with your help, of course) I will now be sinning in so doing.

God: But by the same token, you place me in a double bind. I am willing to leave you free will or remove it as you choose, but neither alternative satisfies you. I wish to help you, but it seems I cannot.

Mortal: True!

God: But since it is not my fault, why are you still angry with me?

Mortal: For having placed me in such a horrible predicament in first place!

God: But, according to you, there is nothing satisfactory I could have done.

Mortal: You mean there is nothing satisfactory you can now do, that does not mean that there is nothing you could have done.

God: Why? What could I have done?

Mortal: Obviously you should never have given me free will in the first place. Now that you have given it to me, it is too late -- anything I do will be bad. But you should never have given it to me in the first place.

God: Oh, that's it! Why would it have been better had I never given it to you?

Mortal: Because then I never would have been capable of sinning at all.

God: Well, I'm always glad to learn from my mistakes.

Mortal: What!

God: I know, that sounds sort of self-blasphemous, doesn't it? It almost involves a logical paradox! On the one hand, as you have been taught, it is morally wrong for any sentient being to claim that I am capable of making mistakes. On the other hand, I have the right to do anything. But I am also a sentient being. So the question is, Do, I or do I not have the right to claim that I am capable of making mistakes?

Mortal: That is a bad joke! One of your premises is simply false. I have not been taught that it is wrong for any sentient being to doubt your omniscience, but only for a mortal to doubt it. But since you are not mortal, then you are obviously free from this injunction.

God: Good, so you realize this on a rational level. Nevertheless, you did appear shocked when I said, "I am always glad to learn from my mistakes."

Mortal: Of course I was shocked. I was shocked not by your self-blasphemy (as you jokingly called it), not by the fact that you had no right to say it, but just by the fact that you did say it, since I have been taught that as a matter of fact you don't make mistakes. So I was amazed that you claimed that it is possible for you to make mistakes.

God: I have not claimed that it is possible. All I am saying is that if I make mistakes, I will be happy to learn from them. But this says nothing about whether the if has or ever can be realized.

Mortal: Let's please stop quibbling about this point. Do you or do you not admit it was a mistake to have given me free will?

God: Well now, this is precisely what I propose we should investigate. Let me review your present predicament. You don't want to have free will because with free will you can sin, and you don't want to sin. (Though I still find this puzzling; in a way you must want to sin, or else you wouldn't. But let this pass for now.) On the other hand, if you agreed to give up free will, then you would now be responsible for the acts of the future. Ergo, I should never have given you free will in the first place.

Mortal: Exactly!

God: I understand exactly how you feel. Many mortals -- even some theologians -- have complained that I have been unfair in that it was I, not they, who decided that they should have free will, and then I hold them responsible for their actions. In other words, they feel that they are expected to live up to a contract with me which they never agreed to in the first place.

Mortal: Exactly!

God: As I said, I understand the feeling perfectly. And I can appreciate the justice of the complaint. But the complaint arises only from an unrealistic understanding of the true issues involved. I am about to enlighten you as to what these are, and I think the results will surprise you! But instead of telling you outright, I shall continue to use the Socratic method.

To repeat, you regret that I ever gave you free will. I claim that when you see the true ramifications you will no longer have this regret. To prove my point, I'll tell you what I'm going to do. I am about to create a new universe -- a new space-time continuum. In this new universe will be born a mortal just like you -- for all practical purposes, we might say that you will be reborn. Now, I can give this new mortal -- this new you -- free will or not. What would you like me to do?

Mortal (in great relief): Oh, please! Spare him from having to have free will!

God: All right, I'll do as you say. But you do realize that this new you without free will, will commit all sorts of horrible acts.

Mortal: But they will not be sins since he will have no free will.

God: Whether you call them sins or not, the fact remains that they will be horrible acts in the sense that they will cause great pain to many sentient beings.

Mortal (after a pause): Good God, you have trapped me again! Always the same game! If I now give you the go-ahead to create this new creature with no free will who will nevertheless commit atrocious acts, then true enough he will not be sinning, but I again will be the sinner to sanction this.

God: In that case, I'll go you one better! Here, I have already decided whether to create this new you with free will or not. Now, I am writing my decision on this piece of paper and I won't show it to you until later. But my decision is now made and is absolutely irrevocable. There is nothing you can possibly do to alter it; you have no responsibility in the matter. Now, what I wish to know is this: Which way do you hope I have decided? Remember now, the responsibility for the decision falls entirely on my shoulders, not yours. So you can tell me perfectly honestly and without any fear, which way do you hope I have decided?

Mortal (after a very long pause): I hope you have decided to give him free will.

God: Most interesting! I have removed your last obstacle! If I do not give him free will, then no sin is to be imputed to anybody. So why do you hope I will give him free will?

Mortal: Because sin or no sin, the important point is that if you do not give him free will, then (at least according to what you have said) he will go around hurting people, and I don't want to see people hurt.

GOD (with an infinite sigh of relief): At last! At last you see the real point!

Mortal: What point is that?

God: That sinning is not the real issue! The important thing is that people as well as other sentient beings don't get hurt!

Mortal: You sound like a utilitarian!

God: I am a utilitarian!

Mortal: What!

God: Whats or no whats, I am a utilitarian. Not a unitarian, mind you, but a utilitarian.

Mortal: I just can't believe it!

God: Yes, I know, your religious training has taught you otherwise. You have probably thought of me more like a Kantian than a utilitarian, but your training was simply wrong.

Mortal: You leave me speechless!

God: I leave you speechless, do I! Well, that is perhaps not too bad a thing -- you have a tendency to speak too much as it is. Seriously, though, why do you think I ever did give you free will in the first place?

Mortal: Why did you? I never have thought much about why you did; all I have been arguing for is that you shouldn't have! But why did you? I guess all I can think of is the standard religious explanation: Without free will, one is not capable of meriting either salvation or damnation. So without free will, we could not earn the right to eternal life.

God: Most interesting! I have eternal life; do you think I have ever done anything to merit it?

Mortal: Of course not! With you it is different. You are already so good and perfect (at least allegedly) that it is not necessary for you to merit eternal life.

God: Really now? That puts me in a rather enviable position, doesn't it?

Mortal: I don't think I understand you.

God: Here I am eternally blissful without ever having to suffer or make sacrifices or struggle against evil temptations or anything like that. Without any of that type of "merit", I enjoy blissful eternal existence. By contrast, you poor mortals have to sweat and suffer and have all sorts of horrible conflicts about morality, and all for what? You don't even know whether I really exist or not, or if there really is any afterlife, or if there is, where you come into the picture. No matter how much you try to placate me by being "good," you never have any real assurance that your "best" is good enough for me, and hence you have no real security in obtaining salvation. Just think of it! I already have the equivalent of "salvation" -- and have never had to go through this infinitely lugubrious process of earning it. Don't you ever envy me for this?

Mortal: But it is blasphemous to envy you!

God: Oh come off it! You're not now talking to your Sunday school teacher, you are talking to me. Blasphemous or not, the important question is not whether you have the right to be envious of me but whether you are. Are you?

Mortal: Of course I am!

God: Good! Under your present world view, you sure should be most envious of me. But I think with a more realistic world view, you no longer will be. So you really have swallowed the idea which has been taught you that your life on earth is like an examination period and that the purpose of providing you with free will is to test you, to see if you merit blissful eternal life. But what puzzles me is this: If you really believe I am as good and benevolent as I am cracked up to be, why should I require people to merit things like happiness and eternal life? Why should I not grant such things to everyone regardless of whether or not he deserves them?

Mortal: But I have been taught that your sense of morality -- your sense of justice -- demands that goodness be rewarded with happiness and evil be punished with pain.

God: Then you have been taught wrong.

Mortal: But the religious literature is so full of this idea! Take for example Jonathan Edwards's "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God." How he describes you as holding your enemies like loathsome scorpions over the flaming pit of hell, preventing them from falling into the fate that they deserve only by dint of your mercy.

God: Fortunately, I have not been exposed to the tirades of Mr. Jonathan Edwards. Few sermons have ever been preached which are more misleading. The very title "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" tells its own tale. In the first place, I am never angry. In the second place, I do not think at all in terms of "sin." In the third place, I have no enemies.

Mortal: By that do you mean that there are no people whom you hate, or that there are no people who hate you?

God: I meant the former although the latter also happens to be true.

Mortal: Oh come now, I know people who have openly claimed to have hated you. At times I have hated you!

God: You mean you have hated your image of me. That is not the same thing as hating me as I really am.

Mortal: Are you trying to say that it is not wrong to hate a false conception of you, but that it is wrong to hate you as you really are?

God: No, I am not saying that at all; I am saying something far more drastic! What I am saying has absolutely nothing to do with right or wrong. What I am saying is that one who knows me for what I really am would simply find it psychologically impossible to hate me.

Mortal: Tell me, since we mortals seem to have such erroneous views about your real nature, why don't you enlighten us? Why don't you guide us the right way?

God: What makes you think I'm not?

Mortal: I mean, why don't you appear to our very senses and simply tell us that we are wrong?

GOD: Are you really so naive as to believe that I am the sort of being which can appear to your senses? It would be more correct to say that I am your senses.

Mortal (astonished): You are my senses?

God: Not quite, I am more than that. But it comes closer to the truth than the idea that I am perceivable by the senses. I am not an object; like you, I am a subject, and a subject can perceive, but cannot be perceived. You can no more see me than you can see your own thoughts. You can see an apple, but the event of your seeing an apple is itself not seeable. And I am far more like the seeing of an apple than the apple itself.

Mortal: If I can't see you, how do I know you exist?

God: Good question! How in fact do you know I exist?

Mortal: Well, I am talking to you, am I not?

God: How do you know you are talking to me? Suppose you told a psychiatrist, "Yesterday I talked to God." What do you think he would say?

Mortal: That might depend on the psychiatrist. Since most of them are atheistic, I guess most would tell me I had simply been talking to myself.

God: And they would be right!

Mortal: What? You mean you don't exist?

God: You have the strangest faculty of drawing false conclusions! Just because you are talking to yourself, it follows that I don't exist?

Mortal: Well, if I think I am talking to you, but I am really talking to myself, in what sense do you exist?

God: Your question is based on two fallacies plus a confusion. The question of whether or not you are now talking to me and the question of whether or not I exist are totally separate. Even if you were not now talking to me (which obviously you are), it still would not mean that I don't exist.

Mortal: Well, all right, of course! So instead of saying "if I am talking to myself, then you don't exist," I should rather have said, "if I am talking to myself, then I obviously am not talking to you."

God: A very different statement indeed, but still false.

Mortal: Oh, come now, if I am only talking to myself, then how can I be talking to you?

God: Your use of the word "only" is quite misleading! I can suggest several logical possibilities under which your talking to yourself does not imply that you are not talking to me.

Mortal: Suggest just one!

God: Well, obviously one such possibility is that you and I are identical.

Mortal: Such a blasphemous thought -- at least had I uttered it!

God: According to some religions, yes. According to others, it is the plain, simple, immediately perceived truth.

Mortal: So the only way out of my dilemma is to believe that you and I are identical?

God: Not at all! This is only one way out. There are several others. For example, it may be that you are part of me, in which case you may be talking to that part of me which is you. Or I may be part of you, in which case you may be talking to that part of you which is me. Or again, you and I might partially overlap, in which case you may be talking to the intersection and hence talking both to you and to me. The only way your talking to yourself might seem to imply that you are not talking to me is if you and I were totally disjoint -- and even then, you could conceivably be talking to both of us.

Mortal: So you claim you do exist.

God: Not at all. Again you draw false conclusions! The question of my existence has not even come up. All I have said is that from the fact that you are talking to yourself one cannot possibly infer my nonexistence, let alone the weaker fact that you are not talking to me.

Mortal: All right, I'll grant your point! But what I really want to know is do you exist?

God: What a strange question!

Mortal: Why? Men have been asking it for countless millennia.

God: I know that! The question itself is not strange; what I mean is that it is a most strange question to ask of me!

Mortal: Why?

God: Because I am the very one whose existence you doubt! I perfectly well understand your anxiety. You are worried that your present experience with me is a mere hallucination. But how can you possibly expect to obtain reliable information from a being about his very existence when you suspect the nonexistence of the very same being?

Mortal: So you won't tell me whether or not you exist?

God: I am not being willful! I merely wish to point out that no answer I could give could possibly satisfy you. All right, suppose I said, "No, I don't exist." What would that prove? Absolutely nothing! Or if I said, "Yes, I exist." Would that convince you? Of course not!

Mortal: Well, if you can't tell me whether or not you exist, then who possibly can?

God: That is something which no one can tell you. It is something which only you can find out for yourself.

Mortal: How do I go about finding this out for myself?

God: That also no one can tell you. This is another thing you will have to find out for yourself.

Mortal: So there is no way you can help me?

God: I didn't say that. I said there is no way I can tell you. But that doesn't mean there is no way I can help you.

Mortal: In what manner then can you help me?

God: I suggest you leave that to me! We have gotten sidetracked as it is, and I would like to return to the question of what you believed my purpose to be in giving you free will. Your first idea of my giving you free will in order to test whether you merit salvation or not may appeal to many moralists, but the idea is quite hideous to me. You cannot think of any nicer reason -- any more humane reason -- why I gave you free will?

Mortal: Well now, I once asked this question of an Orthodox rabbi. He told me that the way we are constituted, it is simply not possible for us to enjoy salvation unless we feel we have earned it. And to earn it, we of course need free will.

God: That explanation is indeed much nicer than your former but still is far from correct. According to Orthodox Judaism, I created angels, and they have no free will. They are in actual sight of me and are so completely attracted by goodness that they never have even the slightest temptation toward evil. They really have no choice in the matter. Yet they are eternally happy even though they have never earned it. So if your rabbi's explanation were correct, why wouldn't I have simply created only angels rather than mortals?

Mortal: Beats me! Why didn't you?

God: Because the explanation is simply not correct. In the first place, I have never created any ready-made angels. All sentient beings ultimately approach the state which might be called "angelhood." But just as the race of human beings is in a certain stage of biologic evolution, so angels are simply the end result of a process of Cosmic Evolution. The only difference between the so-called saint and the so-called sinner is that the former is vastly older than the latter. Unfortunately it takes countless life cycles to learn what is perhaps the most important fact of the universe -- evil is simply painful. All the arguments of the moralists -- all the alleged reasons why people shouldn't commit evil acts -- simply pale into insignificance in light of the one basic truth that evil is suffering.

No, my dear friend, I am not a moralist. I am wholly a utilitarian. That I should have been conceived in the role of a moralist is one of the great tragedies of the human race. My role in the scheme of things (if one can use this misleading expression) is neither to punish nor reward, but to aid the process by which all sentient beings achieve ultimate perfection.

Mortal: Why did you say your expression is misleading?

God: What I said was misleading in two respects. First of all it is inaccurate to speak of my role in the scheme of things. I am the scheme of things. Secondly, it is equally misleading to speak of my aiding the process of sentient beings attaining enlightenment. I am the process. The ancient Taoists were quite close when they said of me (whom they called "Tao") that I do not do things, yet through me all things get done. In more modem terms, I am not the cause of Cosmic Process, I am Cosmic Process itself. I think the most accurate and fruitful definition of me which man can frame -- at least in his present state of evolution -- is that I am the very process of enlightenment. Those who wish to think of the devil (although I wish they wouldn't!) might analogously define him as the unfortunate length of time the process takes. In this sense, the devil is necessary; the process simply does take an enormous length of time, and there is absolutely nothing I can do about it. But, I assure you, once the process is more correctly understood, the painful length of time will no longer be regarded as an essential limitation or an evil. It will be seen to be the very essence of the process itself. I know this is not completely consoling to you who are now in the finite sea of suffering, but the amazing thing is that once you grasp this fundamental attitude, your very finite suffering will begin to diminish -- ultimately to the vanishing point.

Mortal: I have been told this, and I tend to believe it. But suppose I personally succeed in seeing things through your eternal eyes. Then I will be happier, but don't I have a duty to others?

GOD (laughing): You remind me of the Mahayana Buddhists! Each one says, "I will not enter Nirvana until I first see that all other sentient beings do so." So each one waits for the other fellow to go first. No wonder it takes them so long! The Hinayana Buddhist errs in a different direction. He believes that no one can be of the slightest help to others in obtaining salvation; each one has to do it entirely by himself. And so each tries only for his own salvation. But this very detached attitude makes salvation impossible. The truth of the matter is that salvation is partly an individual and partly a social process. But it is a grave mistake to believe -- as do many Mahayana Buddhists -- that the attaining of enlightenment puts one out of commission, so to speak, for helping others. The best way of helping others is by first seeing the light oneself.

Mortal: There is one thing about your self-description which is somewhat disturbing. You describe yourself essentially as a process. This puts you in such an impersonal light, and so many people have a need for a personal God.

God: So because they need a personal God, it follows that I am one?

Mortal: Of course not. But to be acceptable to a mortal a religion must satisfy his needs.

God: I realize that. But the so-called "personality" of a being is really more in the eyes of the beholder than in the being itself. The controversies which have raged, about whether I am a personal or an impersonal being are rather silly because neither side is right or wrong. From one point of view, I am personal, from another, I am not. It is the same with a human being. A creature from another planet may look at him purely impersonally as a mere collection of atomic particles behaving according to strictly prescribed physical laws. He may have no more feeling for the personality of a human than the average human has for an ant. Yet an ant has just as much individual personality as a human to beings like myself who really know the ant. To look at something impersonally is no more correct or incorrect than to look at it personally, but in general, the better you get to know something, the more personal it becomes. To illustrate my point, do you think of me as a personal or impersonal being?

Mortal: Well, I'm talking to you, am I not?

God: Exactly! From that point of view, your attitude toward me might be described as a personal one. And yet, from another point of view -- no less valid -- I can also be looked at impersonally.

Mortal: But if you are really such an abstract thing as a process, I don't see what sense it can make my talking to a mere "process."

God: I love the way you say "mere." You might just as well say that you are living in a "mere universe." Also, why must everything one does make sense? Does it make sense to talk to a tree?

Mortal: Of course not!

God: And yet, many children and primitives do just that.

Mortal: But I am neither a child nor a primitive.

God: I realize that, unfortunately.

Mortal: Why unfortunately?

God: Because many children and primitives have a primal intuition which the likes of you have lost. Frankly, I think it would do you a lot of good to talk to a tree once in a while, even more good than talking to me! But we seem always to be getting sidetracked! For the last time, I would like us to try to come to an understanding about why I gave you free will.

Mortal: I have been thinking about this all the while.

God: You mean you haven't been paying attention to our conversation?

Mortal: Of course I have. But all the while, on another level, I have been thinking about it.

God: And have you come to any conclusion?

Mortal: Well, you say the reason is not to test our worthiness. And you disclaimed the reason that we need to feel that we must merit things in order to enjoy them. And you claim to be a utilitarian. Most significant of all, you appeared so delighted when I came to the sudden realization that it is not sinning in itself which is bad but only the suffering which it causes.

God: Well of course! What else could conceivably be bad about sinning?

Mortal: All right, you know that, and now I know that. But all my life I unfortunately have been under the influence of those moralists who hold sinning to be bad in itself. Anyway, putting all these pieces together, it occurs to me that the only reason you gave free will is because of your belief that with free will, people will tend to hurt each other -- and themselves -- less than without free will.

God: Bravo! That is by far the best reason you have yet given! I can assure you that had I chosen to give free will, that would have been my very reason for so choosing.

Mortal: What! You mean to say you did not choose to give us free will?

God: My dear fellow, I could no more choose to give you free will than I could choose to make an equilateral triangle equiangular. I could choose to make or not to make an equilateral triangle in the first place, but having chosen to make one, I would then have no choice but to make it equiangular.

Mortal: I thought you could do anything!

God: Only things which are logically possible. As St. Thomas said, "It is a sin to regard the fact that God cannot do the impossible, as a limitation on His powers." I agree, except that in place of his using the word sin I would use the term error.

Mortal: Anyhow, I am still puzzled by your implication that you did not choose to give me free will.

God: Well, it is high time I inform you that the entire discussion -- from the very beginning -- has been based on one monstrous fallacy! We have been talking purely on a moral level -- you originally complained that I gave you free will, and raised the whole question as to whether I should have. It never once occurred to you that I had absolutely no choice in the matter.

Mortal: I am still in the dark!

God: Absolutely! Because you are only able to look at it through the eyes of a moralist. The more fundamental metaphysical aspects of the question you never even considered.

Mortal: I still do not see what you are driving at.

God: Before you requested me to remove your free will, shouldn't your first question have been whether as a matter of fact you do have free will?

Mortal: That I simply took for granted.

God: But why should you?

Mortal: I don't know. Do I have free will?

God: Yes.

Mortal: Then why did you say I shouldn't have taken it for granted?

God: Because you shouldn't. Just because something happens to be true, it does not follow that it should be taken for granted.

Mortal: Anyway, it is reassuring to know that my natural intuition about having free will is correct. Sometimes I have been worried that determinists are correct.

God: They are correct.

Mortal: Wait a minute now, do I have free will or don't I?

God: I already told you you do. But that does not mean that determinism is incorrect.

Mortal: Well, are my acts determined by the laws of nature or aren't they?

God: The word determined here is subtly but powerfully misleading and has contributed so much to the confusions of the free will versus determinism controversies. Your acts are certainly in accordance with the laws of nature, but to say they are determined by the laws of nature creates a totally misleading psychological image which is that your will could somehow be in conflict with the laws of nature and that the latter is somehow more powerful than you, and could "determine" your acts whether you liked it or not. But it is simply impossible for your will to ever conflict with natural law. You and natural law are really one and the same.

Mortal: What do you mean that I cannot conflict with nature? Suppose I were to become very stubborn, and I determined not to obey the laws of nature. What could stop me? If I became sufficiently stubborn even you could not stop me!

God: You are absolutely right! I certainly could not stop you. Nothing could stop you. But there is no need to stop you, because you could not even start! As Goethe very beautifully expressed it, "In trying to oppose Nature, we are, in the very process of doing so, acting according to the laws of nature!" Don't you see that the so-called "laws of nature" are nothing more than a description of how in fact you and other beings do act? They are merely a description of how you act, not a prescription of of how you should act, not a power or force which compels or determines your acts. To be valid a law of nature must take into account how in fact you do act, or, if you like, how you choose to act.

Mortal: So you really claim that I am incapable of determining to act against natural law?

God: It is interesting that you have twice now used the phrase "determined to act" instead of "chosen to act." This identification is quite common. Often one uses the statement "I am determined to do this" synonymously with "I have chosen to do this." This very psychological identification should reveal that determinism and choice are much closer than they might appear. Of course, you might well say that the doctrine of free will says that it is you who are doing the determining, whereas the doctrine of determinism appears to say that your acts are determined by something apparently outside you. But the confusion is largely caused by your bifurcation of reality into the "you" and the "not you." Really now, just where do you leave off and the rest of the universe begin? Or where does the rest of the universe leave off and you begin? Once you can see the so-called "you" and the so-called "nature" as a continuous whole, then you can never again be bothered by such questions as whether it is you who are controlling nature or nature who is controlling you. Thus the muddle of free will versus determinism will vanish. If I may use a crude analogy, imagine two bodies moving toward each other by virtue of gravitational attraction. Each body, if sentient, might wonder whether it is he or the other fellow who is exerting the "force." In a way it is both, in a way it is neither. It is best to say that it is the configuration of the two which is crucial.

Mortal: You said a short while ago that our whole discussion was based on a monstrous fallacy. You still have not told me what this fallacy is.

God: Why, the idea that I could possibly have created you without free will! You acted as if this were a genuine possibility, and wondered why I did not choose it! It never occurred to you that a sentient being without free will is no more conceivable than a physical object which exerts no gravitational attraction. (There is, incidentally, more analogy than you realize between a physical object exerting gravitational attraction and a sentient being exerting free will!) Can you honestly even imagine a conscious being without free will? What on earth could it be like? I think that one thing in your life that has so misled you is your having been told that I gave man the gift of free will. As if I first created man, and then as an afterthought endowed him with the extra property of free will. Maybe you think I have some sort of "paint brush" with which I daub some creatures with free will and not others. No, free will is not an "extra"; it is part and parcel of the very essence of consciousness. A conscious being without free will is simply a metaphysical absurdity.

Mortal: Then why did you play along with me all this while discussing what I thought was a moral problem, when, as you say, my basic confusion was metaphysical?

God: Because I thought it would be good therapy for you to get some of this moral poison out of your system. Much of your metaphysical confusion was due to faulty moral notions, and so the latter had to be dealt with first.

And now we must part -- at least until you need me again. I think our present union will do much to sustain you for a long while. But do remember what I told you about trees. Of course, you don't have to literally talk to them if doing so makes you feel silly. But there is so much you can learn from them, as well as from the rocks and streams and other aspects of nature. There is nothing like a naturalistic orientation to dispel all these morbid thoughts of "sin" and "free will" and "moral responsibility." At one stage of history, such notions were actually useful. I refer to the days when tyrants had unlimited power and nothing short of fears of hell could possibly restrain them. But mankind has grown up since then, and this gruesome way of thinking is no longer necessary.

It might be helpful to you to recall what I once said through the writings of the great Zen poet Seng-Ts'an:

If you want to get the plain truth, Be not concerned with right and wrong. The conflict between right and wrong Is the sickness of the mind.

-- Raymond M. Smullyan, 1977 source: http://www.mit.edu/people/dpolicar/writing/prose/text/godTaoist.html

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Glenn Ford, “The Big Heat” (Fritz Lang, 1953).

175 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pandora, William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Medium: oil, canvas

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gotán

yo no escribí ese libro en todo caso me golpeaban me sufrían me sacaban palabras yo no escribí ese libro entiéndanlo así, estará mejor o muy peor visto nomás que la poesía gira en sus propios brazos nada teniendo al fin que ver con ella a ver testículos los míos vuelen pero a ver si se dejan de doler hay que dejarme solo furia bajo mis capas de tabaco Hay que dormirme el corazón el dulce no da más bestias de amor que me lo comen yo nunca escribí libros

De Cólera buey (1971) / Juan Gelman.

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It is, in fact, not always sunny in Philadelphia. To avoid the rain today, we suggest taking shelter in the Museum. Don’t forget your umbrella.

“A Wet Day on the Boulevard - Paris,” 1894 (negative); 1897 (photogravure), by Alfred Stieglitz

“Street Scene,” c. 1955, by Olivier Foss © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

“Oh Lawd, Please Take Away the Rain!,” 1940, by Lamar Baker

“Rain,” 1889, by Vincent van Gogh

“Singing in the Rain,” 1950 (negative); 1970 (print), by Barbara Morgan © Barbara Morgan, the Barbara Morgan Archive

201 notes

·

View notes