Text

Recursion: Model Collapse

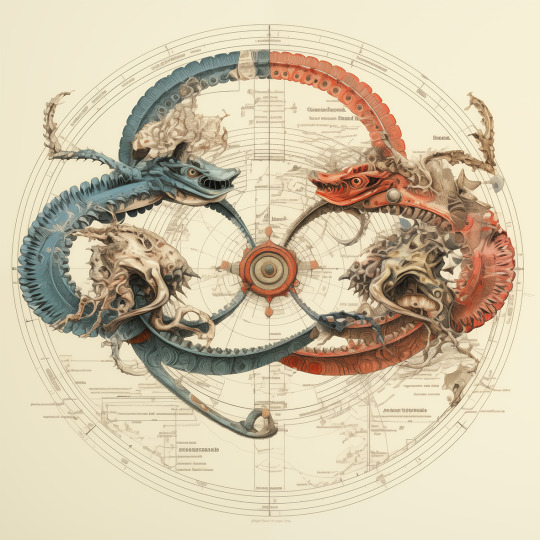

The ouroboros, an ancient symbol depicting a serpent devouring its own tail, lends itself as a metaphor for the evolving recursive feedback loop within artificial intelligence. Generative AI models increasingly consume the very content they produce on the internet. AI is starting to learn predominantly from itself.

AI image-generating platforms like Midjourney and DALL-E rapidly create novel content by drawing from the internet as their primary source material. They do this by 'scraping' data from various image sources, social media, and stock image sites. Specifically, these AI systems seek out image-text pairs. They compile vast datasets of captioned images that effectively subsume large portions of the internet, serving as a surrogate for human creativity.

When AI is trained on synthetic data prone to error, it faces significant challenges in fulfilling its core functions. Part of AI’s role is to identify, organise, and categorise the boundless content that constitutes the internet landscape, making it comprehensible for us humans. However, as AI increasingly generates images and then trains on its own unclassified content, it risks leading to what researchers term "model collapse." This phenomenon occurs when the AI-generated content lacks the accuracy of the original data, resulting in a gradual degradation of the model’s outputs.

Model collapse represents a critical juncture, raising the question: what happens if the information contained within the internet begins to degrade? Would subsequent image production by AI open up new realms of diversity, or would it simply perpetuate more of the same?

The more of the same scenario is reminiscent of the grey goo hypothesis, a concept that emerged in discussions about the potential dangers of future technologies, particularly self-replicating machines. Popularised by Eric Drexler in his 1986 book Engines of Creation, grey goo refers to a situation where self-replicating nanobots, designed to perform specific tasks like repairing tissues or constructing materials, spiral out of control. These tiny machines could potentially consume all available bio-matter, converting it into more of themselves, ultimately covering the planet in a homogeneous "grey goo" that eradicates all other forms of life.

The opposite effect might also be a possibility. AI could create fertile ground for new creations and lifeforms, offering something beyond our present classification systems. Instead of a homogenised internet, model collapse might open up its territories, flooding them with unclassified, fantastical spectres that defy data collection and categorization.

In this fertile digital chaos, the emergence of new forms of 'life'—whether digital, conceptual, or even biological—become possible. Just as biological life on Earth has historically responded to environmental pressures through mutation and adaptation creating the vast diversity of species we see today, so too could the digital landscape undergo similar transformations. Mutations, in the biological sense, are random changes in the genetic code that sometimes result in new traits, which can either flourish or fail depending on the environment. Similarly, as AI-generated content proliferates and diverges from its sources, these "mutations" in data could give rise to new kinds of digital entities—ones that might not conform to previous taxonomic systems, but could evolve to thrive in this new, uncharted environment. Just as life on Earth has branched into countless forms, each adapted to its niche, so too could digital lifeforms diversify, exploring new hybrid ecosystems of digital and synthetic biology.

Over time, these new digital entities could challenge our very definitions of life and intelligence. What begins as a mere byproduct of model collapse—AI learning from its own degraded outputs—could evolve into a new Cambrian explosion, a period of rapid diversification similar to the one that occurred on Earth hundreds of millions of years ago. In this scenario, AI's role would shift from merely organising and categorising human knowledge to participating in the creation of entirely new realms of existence.

As AI continues to develop without a clear, unified goal, we are not ultimately in control of its trajectory or its impact on future life. Rather than merely enlightening the world as we know it, these emergent technologies could reveal it to be far stranger and more complex than we ever imagined.

0 notes

Text

Rethinking Death Through Regeneration and Resurrection Ecology

The history of the world, as natural history, is nothing more than a stratification of events and processes that are never definitively ‘dead and buried’, but which continue to flow and exert an active force from a lower, or even subterranean, dimension than the present—events and processes that can also reappear in an altered form, upsetting our temporal perception. This characteristic pluriversality amounts to the preeminence of reality over imagination, i.e. the hierarchical superiority of natural processes over thought.

- Chapter ‘For a chaotic vision of time’, Gruppo di Nun, Revolutionary Demonology

Death in secular societies is often viewed as the ultimate, irreversible conclusion to life. This perception is deeply rooted in our understanding of human biological mortality, where once the brain stops functioning and the heart ceases to beat, life is considered to be over, with no continuation beyond the bodily processes. This perspective is not universal, it's profoundly influenced by cultural, religious, and philosophical belief systems that offer different interpretations of what happens after the physical body ceases to function. In many spiritual and religious traditions death is not seen as the end of life but rather a transition to a different form of existence. For those who believe in reincarnation the end of the physical body does not signify the end, instead it is believed that the soul after leaving the body is reborn into a new one, continuing its journey through successive lives. This cyclical view of life and death suggests that death is merely a passage from one form of life to another, rather than an absolute conclusion.

The idea that human life can be prolonged, renewed, or even reanimated has been portrayed in diverse and evolving ways, from the pages of early science fiction to the screens of modern cinema, and increasingly within scientific laboratories. These portrayals reflect humanity’s enduring fascination with mortality and the relentless pursuit of ways to transcend it.

Real-world efforts by the biotech industry pursue the reversal of ageing and, by extension, death itself. Peter Thiel, the tech billionaire known for his ventures into disruptive technologies, is one of the prominent figures leading the charge against growing old. His investments in biotech firms that focus on anti-aging research aim to challenge the inevitability of death by targeting the biological processes that cause ageing. Thiel and other tech entrepreneurs are exploring various avenues, from cellular reprogramming to extending telomeres—the protective caps on chromosomes that shorten with age. These efforts are rooted in the belief that ageing is a disease that can be cured and that, by doing so, the human lifespan can be dramatically extended, potentially leading to a future where death is no longer an unavoidable fate.

Immortality finds parallels in nature, where certain organisms possess regenerative abilities that defy the typical constraints of life and death. The immortal jellyfish (Turritopsis dohrnii), for instance, can revert to its immature polyp stage after reaching adulthood, effectively resetting its biological clock. This form of biological immortality allows the jellyfish to escape death, at least theoretically, by continuously cycling between life stages. Such natural examples of regeneration challenge our human-centric understanding of mortality, suggesting that life can persist in forms we barely understand.

Resurrection Ecology, which studies species that can revive after long periods of dormancy is an example of how life adapts and persists through extreme environmental conditions. This fascinating field studies the potential for ecosystems to recover or "resurrect" from extreme disturbances by analysing ancient organisms and their genetic material. A notable example involves the freshwater crustacean Daphnia, which can produce eggs that remain dormant in sediments for decades or even centuries. When environmental conditions become favourable again, these eggs can hatch, effectively resurrecting a population that had seemingly vanished. This process not only illustrates the resilience of certain species but also provides valuable insights into how ecosystems might regenerate after severe disruptions, such as climate change or human-induced environmental damage.

The state of the natural world is one of "pluriversality," where even buried processes exert their influence across time, suggesting that nature operates with a chaotic, layered temporality, where the past re-emerges in altered forms, reshaping the present.

Cryptobiosis (literally meaning hidden life), is where the metabolic rate of an organism is reduced to an imperceptible level, showing no visible signs of life.' Cryptobiosis includes anhydrobiosis (life without water), cryobiosis (life at low temperatures), and anoxybiosis (life without oxygen). In the cryptobiotic state, all metabolic procedures stop, preventing reproduction, development, and repair where an organism can live almost indefinitely while it waits for environmental conditions to become better.

Within the human body, certain tissues and organs possess a remarkable ability to regenerate. The liver, for example, can recover from substantial damage by regenerating its lost tissue, a phenomenon that was mythologized in the story of Prometheus. Chained to a rock, Prometheus’s liver was eaten by an eagle each day, only to regenerate by night—a tale that ancient Greeks may have used to symbolise the resilience of this vital organ. Modern science confirms that the liver’s regenerative capacity is indeed exceptional, but it also highlights the limits of human regeneration. While some tissues like the endometrium and fingertips can regenerate to some extent, the loss of limbs or severe damage to the brain remains beyond our bodily capacity to repair.

Scientists are exploring ways to harness the body’s own regenerative mechanisms or induce regeneration in tissues that typically do not regenerate. The goal is to develop therapies that can restore lost or damaged tissues, effectively turning back the biological clock on a cellular level.

Axolotls are remarkable for their ability to regenerate lost or damaged body parts, which has long fascinated scientists, particular for stem cell research. Beyond limbs, axolotls can regenerate vital organs like the heart, lungs, and even segments of their spinal cord, restoring function. They can also regenerate parts of their brain and eyes, something highly unusual in vertebrates. Unlike most animals, they heal without scarring, maintaining the full functionality of the regenerated tissue. This regenerative ability holds potential for human medicine, if researchers can unlock the genetic and cellular processes enabling axolotl regeneration, it might one day be possible to apply these insights to humans. This could revolutionise treatments for injuries like spinal cord damage, heart disease, or limb loss.

These ideas challenge our Western notions of life and death. Traditionally viewed as a final, irreversible state, death can instead be reimagined as a transitional phase—one that contains the potential for the (re)emergence of life, or perhaps that which never dies.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Abiogenesis

Abiogenesis is the leading scientific theory on how life began; that life arose from non-living matter through increasing complexity. This theory raises an immediate question: what defines something as “living” in the first place and who defines this? Where is the tipping point between non-life and life?

Miller-Urey experiment

In 1952, Stanley Miller and Harold Urey conducted the famous Miller-Urey experiment, simulating early Earth conditions to explore how life's building blocks might form naturally. Using a closed system containing water, methane, ammonia, and hydrogen, they introduced electric sparks to mimic lightning. After a week, amino acids, the essential components of proteins, had formed. Their findings suggested that complex organic molecules crucial to ‘life’ could emerge from simpler compounds under the right conditions, lending support to theories about life’s potential origins.

There are various theories as to how the transformation occurs, but nothing is proven. Several scientific papers have attempted to link the process of Abiogenesis to Systems thinking - that life could be an emergent property from the dynamic interaction of different elements.

At this critical moment of environmental and societal crisis, many are arguing for a radical reimagining of life in response to the unsustainable extractive practices of late capitalism. Recent advances, particularly AI, further blur the Western distinctions of life/non life. Machines are evolving forms of agency and decision-making, raising questions around intelligence, consciousness, and sentience.

In Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism, Elizabeth Povinelli examines the Western concept of life, especially through the lens of Indigenous Australian perspectives. Povinelli introduces “geontology” as a framework to understand the impact of late liberal governance on these relationships, suggesting that life and non-life should be rethought to address the ecological and social crises emerging today. Her focus is to ‘unsettle the governance of the difference between Life and Nonlife’ and to make visible the biontological orientation distribution of power. She stresses that the destabilising of life and non life as categories is not just a philosophical exercise of deconstructing binary oppositions, but to analyse the forces that course through these categories. She critiques the tendency to divide existence into "life" and "non-life," arguing that this fails to capture complex relationships between people, land, and non-human entities.

Indigenous belief systems are rooted in Animism where life and death are not rigid categories but phases in a relational cycle where spirits of people, animals, objects and elements are constantly in interaction, all having agency. Death does not separate one from this world but transforms the spirit’s role within it, often enabling it to guide, protect, or support the living and the land. This view fosters relationships where beings coexist, and ancestral spirits, deeply rooted in place, actively contribute to the vitality of the world. In this framework, death is less a termination and more a continuation in a different form, reinforcing the connection between the individual and the ecosystem that sustains all beings. Distinguishing between "living" and "non-living" becomes more or less obsolete, rather, everything is understood as "alive" in its own way, with a unique essence or spirit. It acknowledges that rocks, rivers, wind, and mountains—things that Western science might classify as "non-living"—have intrinsic agency, awareness, or purpose. Animism suggests that all entities, regardless of their physical characteristics, are part of a sentient, interconnected world.

Radical Animism: Reading for the End of the World by Jemma Deer explores the concept of animism in the context of contemporary environmental crises. The book describes how animistic thinking can offer new ways to understand and engage with the world during a time of ecological collapse. Deer rethinks the boundaries between human and non-human life, critiquing the separation imposed by modernity and advocating for a return to a relational understanding of existence. This perspective redefines "living" as a quality that isn’t limited to biology but extends to everything in existence. If we expand our definitions of life, emerging from this animistic potential, can we reconcile with the network of relationships, energies, and inherent agency within all things?

0 notes